Bundles served in death as in life

Posted: February 19, 2024 Filed under: Wonder Trail Leave a comment

Went looking into the idea that even after death Inka nobles clung to power:

People in Andean societies viewed themselves as belonging to family lineages. (Europeans did, too, but lineages were more important in the Andes; the pop-cultural comparison might be The Lord of the Rings, in which characters introduce themselves as “X, son of Y” or “A, of B’s line.”) Royal lineages, called panaqa, were special. Each new emperor was born in one panaqa but created a new one when he took the fringe. To the new panaqa belonged the Inka and his wives and children, along with his retainers and advisers. When the Inka died his panaqa mummified his body. Because the Inka was believed to be an immortal deity, his mummy was treated, logically enough, as if it were still living. Soon after arriving in Qosqo, Pizarro’s companion Miguel de Estete saw a parade of defunct emperors. They were brought out on litters, “seated on their thrones and surrounded by pages and women with flywhisks in their hands, who ministered to them with as much respect as if they had been alive.” Because the royal mummies were not considered dead, their successors obviously could not inherit their wealth. Each Inka’s panaqa retained all of his possessions forever, including his palaces, residences, and shrines; all of his remaining clothes, eating utensils, fingernail parings, and hair clippings; and the tribute from the land he had conquered. In consequence, as Pedro Pizarro realized, “the greater part of the people, treasure, expenses, and vices [in Tawantinsuyu] were under the control of the dead.” The mummies spoke through female mediums who represented the panaqa’s surviving courtiers or their descendants. With almost a dozen immortal emperors jostling for position, high-level Inka society was characterized by ramose political intrigue of a scale that would have delighted the Medici. Emblematically, Wayna Qhapaq could not construct his own villa on Awkaypata—his undead ancestors had used up all the available space. Inka society had a serious mummy problem. After smallpox wiped out much of the political elite, each panaqa tried to move into the vacuum, stoking the passions of the civil war. Different mummies at different times backed different claimants to the Inka throne. After Atawallpa’s victory, his panaqa took the mummy of Thupa Inka from its palace and burned it outside Qosqo—burned it alive, so to speak. And later Atawallpa instructed his men to seize the gold for his ransom as much as possible from the possessions of another enemy panaqa, that of Pachacuti’s mummy.

so says Charles Mann in 1491, required reading. He cites as his sources:

so that’s a weekend sorted.

These Lords had the law and custom of taking that one of their Lords who died and embalming

him, wrapping him up in many fine clothes, and to these Lords they allotted all the service which they had had in life, in order that these bundles [mummies] might be served in death as well as they had been in life. Their service of gold and silver was not touched, nor was anything else which they had, nor were those who served them [removed from] the house without being replaced, and provinces were set aside to give them support. The Lord who entered upon a new reign had to take new servants. His vessels had to be of wood and pottery until there was time to make them of gold and silver, and always those who began to reign carried out all this, and it was for this reason that there was so much treasme in this land, because, as I have said, he who succeeded to the kingdom always hastened to make better vessels and houses [than his predecessors]. And as the greater part of the people, treasure, expenses and vices were under the control of the dead, each dead man had allotted to him an important Indian, and likewise an Indian woman, and whatever these wanted they declared it to be the will of the dead one. Whenever they wished to eat, to drink, they said that the dead ones wished to do that same thing. If they wished to go and divert themselves in the houses of other dead folk, they said the same, for it was customary for the dead to visit one another, and they held great dances and orgies, and sometimes they went to the house of the living, and sometimes the living came to their. At the same time as the dead people, many [living], as well men as women came, saying that they wished to serve, and this was not forbidden them by the living, because all were at liberty to serve these [the dead], each one serving the dead person he desired to serve. These dead folk had great number of the chief people [in their service], as well men as women, because they lived very licentiously, the men having the women as concubines, and drinking and eating very lavishly.

Pedro Pizarro goes on to describe a summit with a mummy:

The Marquis sent me [with orders to] go with Don Martin, the interpreter, to speak to this dead man and ask on his [Pizarro’s] behalf that the Indian woman be given to this captain. Then I, who believed that I was going to speak to some living Indian, was taken to a bundle, [like] those of these dead folk, which was seated in a litter, which held him and on one side was the Indian spokesman who spoke for him, and on the other was the Indian woman, both sitting close to the dead man. Then, when we were arrived before the dead one, the interpreter gave the message, and being thus for a short while in suspense and in silence, the Indian man looked at the Indian woman (as I understand it, to find out her wish). Then, after having been thus as I relate it for some time, both the Indians replied to me that it was the will of the Lord the dead one that she go, and so the captain already mentioned carried off the Indian woman, since the Apoo, for thus they called the Marquis, wished it.

Is it not possible they were playing a prank on Pedro Pizarro here? Five hundred years later who can say. It can be agreed the Inca had weird death stuff going on, but you don’t think they were doing weird death stuff in Extremadura, Spain in 1532? The place is littered with pieces of the true cross and the robe Jesus wore at the Last Supper and black Madonnas and churches called like The Holy Blood. They’d been fighting a religious war, the Reconquista, for 700 years.

The Spanish conquest of “Peru” wasn’t an encounter of a normal culture with a weird culture. It was very weird culture x very weird culture. (Weird here defined as strange, difficult to comprehend to us. Not like we’re normal.)

Every fragment of this encounter shatters off in a million weird directions. The truth can never be known. We can only contemplate the few primary sources that survive with awe and wonder.

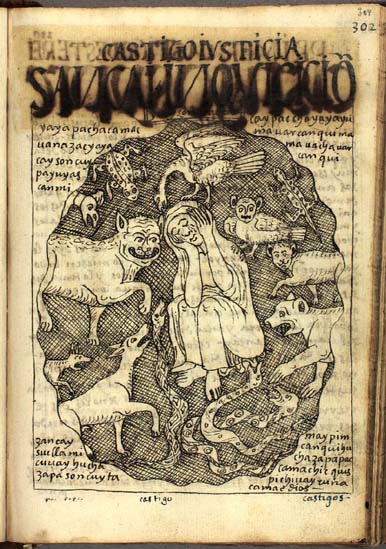

Consider for example Guaman Poma, Falcon Puma’s book.

It was discovered in the Royal Danish Library of Copenhagen in 1908. It’s 1,189 pages long and handwritten and illustrated. Richard Pieschman, the scholar who found it, knew it was a big deal but he soon died. It was not available in English until I believe 1980? The 2006 translation selected, translated and annotated by David Frye has a wild introduction. The 2009 University of Texas edition by the late Roland Hamilton is also good, and free to look at here. Frye:

underlinings from the previous owner. Latin American literature began as something strange and stayed that way.

So, you can see how I’ve only gotten as far as John Hemming. That’s a whole other project. Hemming’s bona fides are that he was on the last expedition in which a British person was killed by an uncontacted tribe.

(The Panará) had had no knowledge of clothes and the swish-swish of Mason’s jeans as he walked had unnerved them.