Hundred in the Hand

Posted: July 22, 2023 Filed under: murders, mysteries, native america, the American West, war Leave a comment

The Sioux were of two minds about winktes but considered them mysterious (wakan) and called on them for certain kinds of magic or sacred power. Sometimes winktes were asked to name children, for which the price was a horse. Sometimes they were asked to read the future. On December 20, 1866, the Sioux, preparing another attack on the soldiers at Fort Phil Kearny, dispatched a winkte on a sorrel horse on a symbolic scout for the enemy. He rode with a black cloth over his head, blowing on a sacred whistle made from the wing bone of an eagle as he dashed back and forth over the landscape, then returned to a group of chiefs with his fist clenched and saying, “I have ten men, five in each hand – do you want them?”

The chiefs said no, that was not enough, they had come ready to fight more enemies than that, and they sent the winkte out again.

Twice more he dashed off on a sorrel horse, blowing his eagle-bone whistle, but each time the number of enemy he brought back in his fists was not enough. When he came back the fourth time he shouted, “Answer me quickly – I have a hundred or more.” At this all the Indians began to shout and yell, and after the battle the next day it was often called the Battle of a Hundred in the Hand.

– so writes Thomas Powers in The Killing of Crazy Horse. In a footnote Powers says “This version of the story of the winkte was told to George Bird Grinnell in 1914 by the Cheyenne White Elk, who took part in the Fetterman fight when he was about seventeen years old. It can be found in George Bird Grinnell, The Fighting Cheyennes, 237-8.” You can also find White Elk’s testimony in Eyewitness to the Fetterman Fight: Indian Views, edited by John H. Monnett and published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

On the morning of the 21st ultimo at about 11 o’clock A.M. my picket on Pilot hill reported the wood train corralled, and threatened by Indians on Sullivan Hills, a mile and a half from the fort. A few shots were heard. Indians also appeared in the brush at the crossing of Piney, by the Virginia City road…

Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman also was well admonished, as well as myself, that we were fighting brave and desperate enemies who sought to make up by cunning and deceit, all the advantages which the white man gains by intelligence and better arms.

Hence my instructions to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman, viz: – “Support the wood train, relieve it and report to me. Do not engage or pursue Indians at its expense. Under no circumstances pursue over the ridge viz; Lodge Trail Ridge, as per map in your possession.”

At 12 o’clock firing was heard towards Peno Creek, beyond Lodge Trail Ridge. A few shots were followed by constant shots, not to be counted. Captain Ten Eyck was immediately dispatched with infantry and the remaining cavalry and two wagons, and ordered to join Colonel Fetterman at all hazards.

The men moved promptly and on the run, but within little more than half an hour from the first shot, and just as the supporting party reached the hill overlooking the scene of action, all firing ceased.

Captain Ten Eyck sent a mounted orderly back with the report that he could see and hear nothing of Fetterman, but that a body of Indians, on the road below him, were challenging him to come down, while larger bodies were in all the valleys for several miles around.

Moving cautiously forward with the wagons, evidently supposed by the enemy to be guns, as mounted men were in advance, he rescued from the spot where the enemy had been nearest, forty nine bodies, including those of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman and Captain F.H. Brown. …

The following morning, finding genuine doubt as to the success of an attempt to recover other bodies, but believing that failure to rescue them would dishearten the command and encourage the Indians who are so particular in this regard, I took eighty men and went to the scene of action..

The scene of action told its story. The road on the little ridge where the final stand took place was strewn with arrow heads, scalps, poles and broken shafts of spears. The arrows that were spent harmlessly from all directions, showed that the command was suddenly overwhelmed, surrounded and cut off while in retreat. Not officer or man survived. A few bodies were found at the north end of the divide over which the road runs just below Lodge Trail Ridge.

…

Fetterman and Brown had each a revolver shot in the left temple. As Brown always declared he would reserve a shot for himself as a last resort, so I am convinced that these two brave men fell, each by the other’s hand, rather than undergo the slow torture inflicted upon others…

The officers who fell believed that no Indian force could overwhelm that number of troops well held in hand.

…

Pools of blood on the road and sloping sides of the narrow divide showed where Indians bled fatally, but their bodies were carried off. I counted sixty five such pools in the space of an acre, and three within ten feet of Lieut. Grummond’s body.

At the northwest or further point, between two rocks, and apparently where the command first fell back from the valley, realizing their danger, I found citizen James S. Wheatly and Isaac Fisher of Blue Springs Nebraska, who, with “Henry rifles”, felt invincible, but fell, one having one hundred and five arrows in his naked body.

The widow and family of Wheatly are here. The cartridge shells about him, told how well they fought.

…

…

I was asked to “send all the bad news”. I do it as far as I can. I give some of the facts as to my men whose bodies I found just at dark, resolved to bring all in viz: –

Mutilations

Eyes torn out and laid on the rocks.

Noses cut off.

Ears cut off.

Chins hewn off.

Teeth chopped out.

Joints of fingers. [sic]Brains taken out and placed on rocks with other members of the body.

Entrails taken out and exposed.

Hands cut off.

Feet cut off.

Arms taken out from socket.

Private parts severed and indecently placed on the person.

Eyes, ears, mouth, and arms penetrated with spear heads, sticks and arrows.

Ribs slashed to separation with knifes.

Sculls [sic] severed in every form from chin to crown.

Muscles of calves, thighs, stomach, breast, back, arms and cheek, taken out.

Punctures upon every sensitive part of the body, even to the soles of the feet and palms of the hand.All this only approximates to the whole truth.

so wrote Colonel H. B Carrington in his report dated Jan 3, 1867, which you can find for yourself here if you’re so inclined.

Fetterman’s march ended on a knoll beside U.S. 87 a few miles below Sheridan—less than a hundred miles from Custer’s blind alley. Today a rough stone barricade encloses the site. A flagpole stands beside a cairn emblazoned with a bronze shield and a summary of the disaster. One farmhouse can be seen about a mile up the road, otherwise there is nothing to look at except a line of telephone poles. Not many people use the old highway, traffic cruises along 1-90 some distance east. Very few tourists leave the freeway to commune with the shade of this arrogant officer who, like Lt. Grattan twelve years earlier, thought a handful of bluecoats could ride straight through the Sioux nation. The black iron gate to this memorial frequently hangs open.

Capt. Fetterman was sucked to death by a stratagem antedating the Punic wars. He met a weak party of Oglalas just out of reach. Naturally he chased them. He almost caught them. A few yards farther—a few more yards. It is said that young Crazy Horse was among these decoys.

Meanwhile, the woodcutters got back safely. Fetterman could not have been very bright because two weeks earlier the Sioux just about bagged him in a similar ambush. From that experience he learned nothing. He entered the trap again. Why? Because he was new to the frontier, because of constitutional arrogance, perhaps because he had been educated at West Point to assume that one American soldier could handle a dozen savages. And he might possibly have been enraged by the decoys shouting in English: “You sons of bitches!”

Dunn, whose ponderous history of these sanguine days appeared in 1886, claims that many years after the fight he was shown an oak war club bristling with spikes—still clotted with blood, hair, and dried brains—which the Oglalas used on Fetterman’s troops. He does not excuse Fetterman, but at the same time he has no very high opinion of Col. Carrington, whom he labels a dress-parade officer. Carrington should not have been assigned to the frontier, says Dunn, he should have been teaching school: “He built a very nice fort, but every attack made on him and his men, during the building, was a surprise. There is nothing to indicate that he ever knew whether there were a thousand or only a hundred Indians within a mile of the fort. He seems to have disapproved of Indians. Perhaps he would have ostracized them socially, if he could have had his way.”

Two experienced civilians, James Wheatley and Isaac Fisher, had joined the party in order to try out their new sixteen-shot Henry repeating rifles. These men especially infuriated the Sioux, probably because they punctured a good many of Red Cloud’s finest before being dropped. Identification was tentative because their faces were reduced to pudding, and one of them—scholars disagree as to which—had been spitted with 105 arrows.

…

John Guthrie was one of the first troopers on the scene. He noted his impressions in a convulsive, agitated style. He wrote that the command lay on the old Holiday coach road near Stoney Creek ford just over a mile from the fort—which is not quite accurate, the true distance being at least twice that far.

The fate of Colonel Fetterman command all my comrades of the detail could see, the Indians on the bluff, the silver flashed with the glorious sunshine, flashed in the hair of the skulking Indians carrying away the clothing of the butchered, with arrows sticking in them, and a number of wolves, hyenas and coyotes hanging about to feast on the flesh of the dead men’s bodies. The dead bodies of our friends at the massacre lay out all night and were not touched or disturbed in any way again, and the cavalry horse of Co. C 2nd, those ferocious and devourers of bodies, did not even touch. Another rather peculiar feature in connection with those massacres is that it is thought by some that those wild animals that eat the dead bodies of the Indians are not so apt to disturb the white victims, and this is accounted for by the fact that salt generally permeates the whole system of the white race, and at least seems to protect to some extent even after death, from the practice of wild animals. Twenty four hours after death Dr. Report at Fort detailed we start to load the dead on the ammunition, all of the Fetterman boys huddled together on the small hill and rock some small trees nearly shot away on the old coach road, near the battle field or Massacre Hill, ammunition boxes we packed them, my comrades on top of the boxes terrible cuts left by the Indians, could not tell Cavalry from the Infantry, all dead bodies stripped naked, crushed skulls, with war clubs ears and noses and legs had been cut off, scalps torn away and the bodies pierced with bullets and arrows, wrist feet and ankles leaving each attached by a tendon. We loaded the officers first. Col. Fetterman of the 27th Infantry, Captain Brown of the 18th Infantry and bugler Footer of Co. C 2nd Cavalry were all huddled together near the rocks, Footer’s skull crushed in, his body on top of the officers … . Sargeant Baker of Co. C 2nd Cavalry, a gunnie sack over his head not scalped, little finger cut off for a gold ring; Lee Bontee the guide found in the brush near by the rest called Little Goose Creek, body full of arrows which had to be broken off to load him … . Some had crosses cut on their breasts, faces to the sky, some crosses cut on the back, face to the ground, a mark cut that we could not find out. We walked on top of their internals and did not know it in the high grass. Picked them up, that is their internals, did not know the soldier they belonged to, so you see the cavalry man got an infantry man’s gutts and an infantry man got a cavalry man’s gutts … .

Only one man, bugler Adolph Metzger, had not been touched. His bugle was so badly dented that he must have gone down swinging it like a club, and for some reason the Indians covered his body with a buffalo robe.

Years later an Oglala named Fire Thunder, who had been sixteen at the time, described with eloquent simplicity the Indian trap. He said that after finding a good place to fight they hid in gullies along both sides of the ridge and sent a few men ahead to coax the soldiers out. After a long wait they heard a shot, which meant soldiers were coming, so they held the nostrils of their ponies to keep them from whinnying at the sight of the American horses. Pretty soon the Oglala decoys came into view. Some were on foot, leading their ponies to make the soldiers think the ponies were tired. Soldiers chased them. The air filled with bullets. But all at once there were more arrows than bullets—so many arrows that they looked like grasshoppers falling on the soldiers. The American horses got loose, Fire Thunder said. Several Indians went after them. He himself did not because he was after wasichus. There was a dog with the soldiers which ran howling up the road toward the fort, but died full of arrows. Horses, dead soldiers, wounded Indians were scattered across the hill “and their blood was frozen, for a storm had come up and it was very cold and getting colder all the time.” Then the Indians picked up their wounded and went away. The ground felt solid underfoot because of the cold. That night there was a blizzard.

– so says Evan S. Connell in Son of the Morning Star.

American Horse (the elder?) drew a representation of the event in a winter count that’s now in the collection of the Smithsonian:

Red Cloud and other Oglala Sioux who took part in that whirlwind affair talked of it afterward to Captain James Cook, who resided for many years near their Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota. Cook says they told him that the white soldiers seemed paralyzed, offered no resistance, and were simply knocked in the head. Old Northern Cheyenne Indians who were there have talked of it to the author. They say that Crazy Mule, a noted Cheyenne worker of magic, performed one of his miracles on that occasion. He caused the soldiers to become dizzy and bewildered, to run aimlessly here or there, to drop their guns, and to fall dead.

– Thomas Marquis in Keep The Last Bullet For Yourself, a valuable source with a provocative title. The manuscript was only published years after Marquis died. Marquis was a doctor on the Northern Cheyenne reservation and spoke to many eyewitnesses.

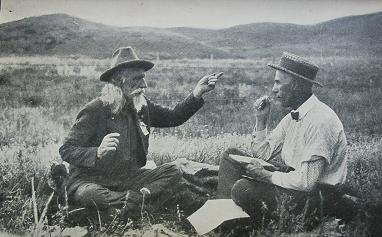

Marquis hearing from the old scout Tom Leforge, from Marquis wiki page

Eerie events on the American plains.

Picture of the site from Google Street View.