His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life by Jonathan Alter

Posted: December 31, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

If you’re wondering why he’s wearing watchface facing in, submariner’s habit, so you could tell time while working the periscope.

As a preteen he castrated hogs, ploughed a field with a mule (Emma), sheered sheep, pulled boil weevils from cotton by hand. By the time he was a teenager he was a slumlord, renting out tenant cabins to black farmers. After he graduated the Naval Academy he went to work for Admiral Rickover, who was inventing the nuclear navy. “Life is a constant fight against stupidity,” Rickover used to say. When the classified Chalk River Laboratories – National Research Experimental reactor nearly melted down, he led a group of twenty four who donned primitive “anti-C” suits and rehearsed removing as many flanges and turning as many valves as possible in an allotted ninety seconds before entering the contaminated space. Their urine and feces was examined for six months afterwards (they turned out to have no ill effects). When his father died, he agonized about what to do, but decided to quit the Navy and go back home without telling his wife, who was furious.

“No matter what happened – if it was a beautiful day or my older son made all As on his report card… underneath it was gnawing wawy because I owned twelve thousand dollars and didn’t know how I was going to pay it,” he would say about the next two years. Around this time he joined the Lions Club, as his father had:

Any time Jimmy wanted a toehold in some distant community, he would speak at one of Georgia’s 180 Lions Clubs, most in small towns.

He became obsessed with the poetry of Dylan Thomas, and it was his efforts that started a movement that led to a stone for Thomas being placed in Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey.

In Georgia at this time, there was a state requirement that busses carrying black kids to black schools had to have their fender painted black. Jimmy Carter was not a leader on integration. “This was a time, I’d say, of very radical elements on both sides,” he would say while he ran for president.

In 1962 the Supreme Court ruling in Baker v Carr enshrined a “one man, one vote” principle. Previously Georgia was organized on a “county unity system,” which meant Fulton County got only three times as many votes as a small rural county, even though it was 200x bigger.

Carter saw that by curbing the power of old courthouse politicians, Baker v. Carr would make a career in politics possible for a moderate like him.

The first time he ran for governor of Georgia he lost. “Show me a good loser and I’ll show you a loser,” was how he felt about that. He resolved to never lose another election. In 1970 he ran again, against Carl Sanders, who had helped bring major league baseball, football and basketball teams to Atlanta for the first time. Carter needed to win both racist George Wallace voters and liberal and black voters.

His solution was to avoid explicit mention of race in favor of class based populist appeals to Wallace voters, as well a overtures to moderates on education, the environment, and efficiency in government.

A research paper about southern populism by 25 year old Jody Powell affected his thinking. Powell would be a close aide all the way to the White House.

Carter shared his technique: “Notice how I didn’t ask for his vote. I said: ‘I want you to consider voting for me.'” At small and midsized campaign events, he would arrive early and park himself by the door so that he shook hands with every person entering the room – a simple and effective gesture neglected by many politicians.

During his inaugural speech as governor, he declared “the time for racial discrimination is over.” About a dozen conservative senators who had supported him walked out. But the speech got him on the cover of Time magazine.

During his term as governor he expected his team to work eighty and ninety hour weeks. He was aggressive, unrelenting, confrontational. Hunter S. Thompson would call Jimmy Carter one of the three meanest men he ever met – the other two being Muhammed Ali and Hells Angels president Sonny Barger.

“The conventional image of a sexy man is one who is hard on the outside and soft on the inside,” Sally Quinn wrote in the Washington Post. “Carter is just the opposite.”

When he ran for president his family was a tremendous advantage. During the Florida primary, Rosalynn and Edna Langford, her son’s mother-in-law, would drive into a town, look for the tallest antenna, and ask the station manager if someone wanted to interview them. Carter’s dynamic mother Lillian, who joined the Peace Corps at age sixty eight, would become a frequent guest on The Tonight Show.

Dick Cheney was working for Carter’s opponent Gerald Ford:

“Everybody knows about Plains Georgia and Lillian. Nobody really knows Ford,” Cheney wrote in a memo. “He never had a hometown. He never had a mother. He never had a childhood as far as the American people are concerned.”

Meanwhile:

Cutting the other way, Billy Carter crisscrossed Texas telling enthusiastic audiences that the Carers had always been conservatives, and that he would shoot Cesar Chavez, leader of the United Farm Workers of America union, if he came on his property.

It was a narrow win. If Ford hadn’t chucked Nelson Rockefeller, if Ford hadn’t said the thing in the debate about Eastern Europe, if.. if…

Exit polls showed that Carter won on pocketbook issues… The improbability of Carter’s victor struck speechwriter Rick Hertzberg who said later that electing him was as close “as the American people have every come to picking someone out of the phone book to be president.”

Hertzberg’s quote does not ring true to me. This was not a random guy. A nuclear engineer, a canny politician, a furious worker, a poet, rigid, deeply strange. As Alter says, comparing his post-presidency to the Clintons and Obamas, Carter was “built differently.” But then again Hertzberg knew him and I didn’t.

The parts of this book about the Carter presidency are mostly quite sad. Frustrations, bad luck, endless problems, prayers, defeats. An almost desperate search for spiritual answers, not even political ones. The great triumph, the Camp David Accords, took up enormous amounts of time and energy. Sadat had already visited Jerusalem, were Israel and Egypt on the road to peace anyway? I don’t know enough about it.

A good man, but not a good president, was and is a widely held opinion. Was he not a good president because he was a good man? Does dealing with the Ayatollah (or Congressional committee chairs) require a nasty operator on the level of Johnson or Nixon? Consider Reagan’s team, who got their hands on Carter’s debate prep book, and almost certainly cut a secret deal with the Iranians that involved selling weapons for the war with Iraq which killed more than a million people.

Was Carter caught between the pious Sunday school teacher and the tough engineer with not enough of the jolly, dealmaking, wink and a handshake stuff you need in our system?

Carter vocally committed the US to “human rights” as president. The resulting hypocrisies are not hard to spot. The Carter administration was effectively advising the Shah of Iran to shoot protestors, to take one example. Can human rights really be a presidential interest in this soiled world?

Can a true follower of Jesus ever be an effective US president?

Maybe the biggest way the Carter presidency ripples through daily life in 2025: deregulation. Trucking, rail, airlines, natural gas. Southwest Airlines, Wal-Mart, Amazon, the shale boom, none of these would be the same without Carter-era deregulation. The consequences are many and mixed, and the result may not have matched the vision. The main stated goal was to fight inflation, massive problem and major part of Carter’s undoing.

Biographies have to make the case for the subject’s significance (otherwise why am I reading?). So they might be biased towards showing a master shaping events. Alter’s Carter doesn’t come off like that, he seems blown about by winds beyond his control.

The book is great by the way, I was very absorbed. Something I should learn more about would be Carter’s relationship to unions, organized labor. In Passage of Power Caro, reporting on LBJ’s first presidential weekend mentions several calls with labor leaders like Walter Reuther. By the next Democratic presidency I hear almost nothing about labor. Jimmy was a business owner, manager and employer. Georgia was not a union friendly state. Maybe there’s a bigger story to be told about the collapse of US labor power between 1963 and 1976. Maybe Carter is a part of that story.

While he was governor Carter launched the Georgia Film Commission, which has had a significant impact on my life, as my friends are always flying to Atlanta to shoot stuff. Los Angeles is being outcompeted as a filming location.

Carter was friends with James Dickey, and helped arrange Georgia as a shooting location for Deliverance and The Longest Yard (using Georgia inmates).

On a recent visit to Atlanta* I had a chance to visit the Carter Library. I thought I might buy my daughter a present at the gift shop. After all, at the Reagan Library the gift shop is enormous, mugs, toys, models, posters, DVDs. At the Carter Library, not so:

Very sparse, not even all of Jimmy’s books.

There’s a replica of the Oval Office as it existed in Carter’s time. A recording of Carter says that tough, strong-willed people he’d known in Georgia would come to see him in the Oval Office, and the aura of the room would strike them dumb, they’d forget what they came to see him about.

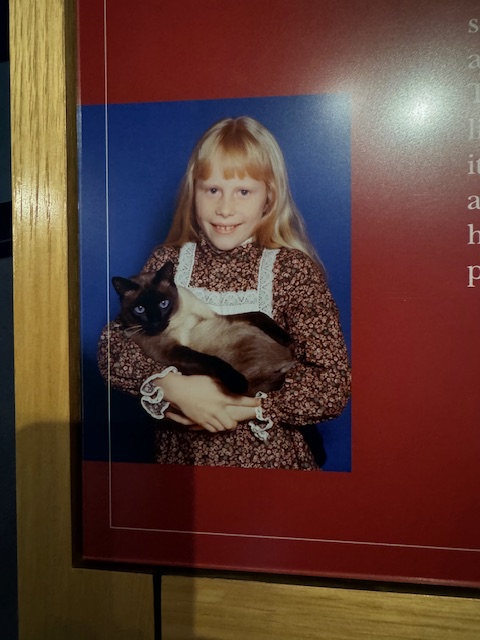

I was very struck by this photo of Amy:

So vulnerable.

*Trip unrelated to Georgia Film Commission, although related to the Ted Turner cable empire, a tentacle of which will air Common Side Effects, premiering Feb. 2, 11:30pm, first airing on Cartoon Network/Adult Swim, streaming on Max next day. Don’t miss!