25.5 Hours (and three hundred years) in Santa Barbara (and Santa Barbara County)

Posted: May 18, 2025 Filed under: the California Condition 1 Comment(this is an excerpt from my book California Getaway, which will be published by Universiteit Utrecht Press in their Amerikaanse avonturenseries, spring 2029*)

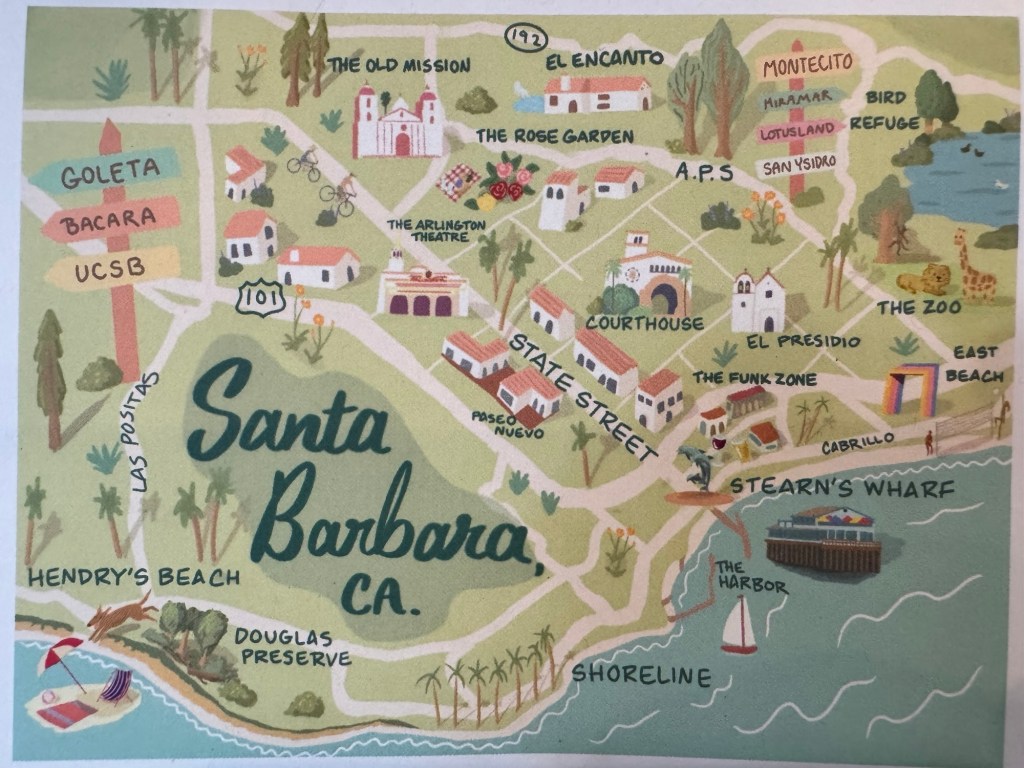

Santa Barbara is divided by both the 101 Highway and the Union Pacific railroad tracks, shared by Amtrak, which run close together. This carves out an area squeezed along the waterfront called “the Funk Zone.” Funky in the sense of curious, unusual, quirky, and the funky taste and smell of unrefined wines. (Not funky in the sense of the African-American music genre: Santa Barbara is barely over 1% black. This may be part of why it was tolerated for there to be a restaurant named Sambo’s right on the beach until the year 2020).

In the Funk Zone a good place for sandwiches is Tamar.

The Coast Starlight bound for Seattle leaves grand, deco Union Station at 9:51am and pulls into Santa Barbara at 12:15pm. That’s assuming it’s on time, not a safe assumption, and assuming the tracks don’t get washed away by the waves. They’re awful close, one day it will happen. You’ll pass the industrial workings of LA, the Big Thunder Mountain country by Santa Susanna, then down into vegetable farms of almost obscene bounty, and then past the surf corner at Rincon, and the world’s safest beach at Carpinteria, and into Santa Barbara.

There’s always at least one college student, one European, and at least one mystery case on the long distance Amtraks.

Walkable, Mediterranean climate, remarkable architecture, a fishing port that’s also a farm market town, a collection point for the freshest produce and the wildest most experimental and interesting wines? Oh, it’s also a college town? The catch? The median home price is around two point five million dollars.

Welcome to Santa Barbara.

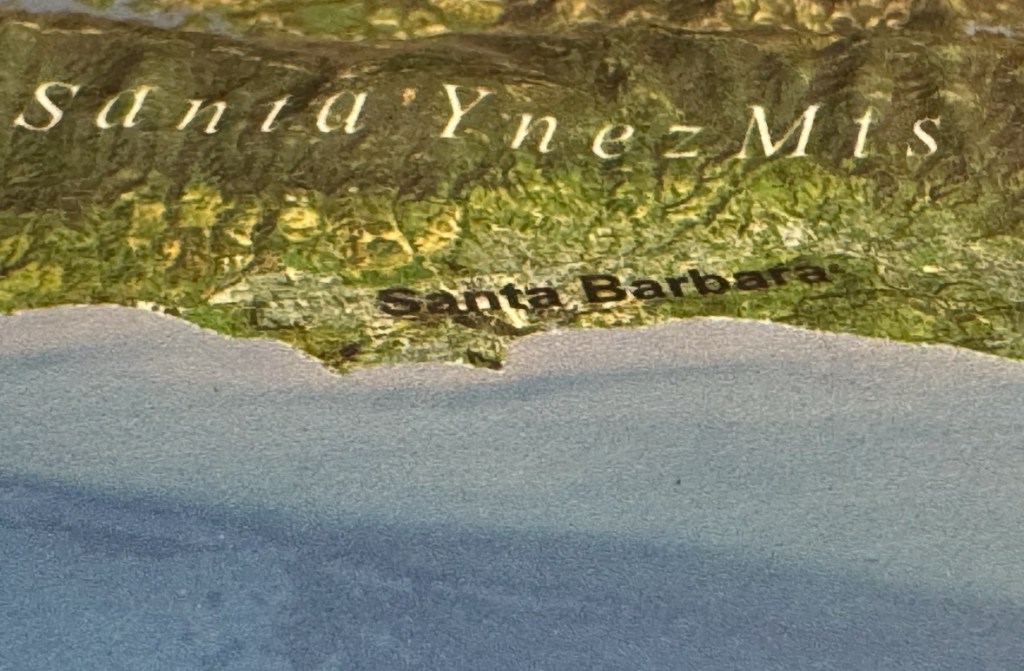

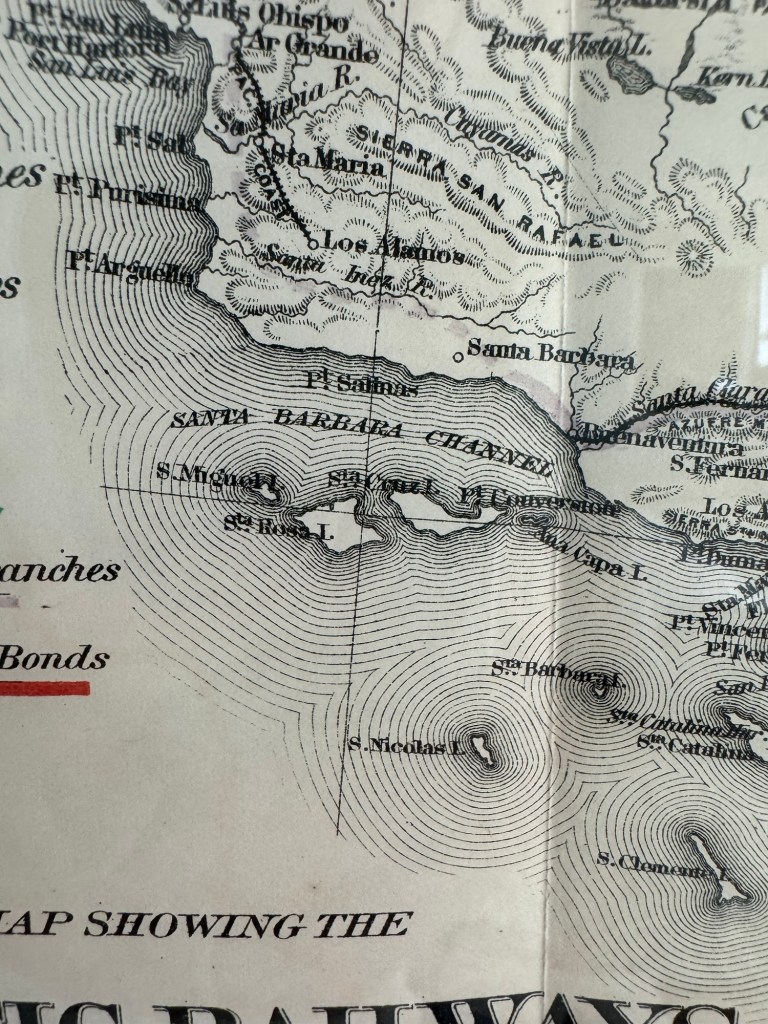

Mountains wall it on the north. On the south is the Santa Barbara Channel, shielded by the Channel Islands and full of fish and urchins. Squid is biggest catch, in dollars. The Chumash were feasting long here before the mission Spanish showed up driving herds of cattle. The archaeological riches found in what’s now Ambassador Park suggest that place was once a burial ground or a gathering place or both. (You hear the word “ceremonial” thrown around with the ancient peoples. What are our ceremonies? Going on vacation?)

The place was visited by Cabrillo and Vizcaino and who knows what other pirates and mariners before the mission was established in 1786. Richard Dana visited in 1834, went to a fandango, and was impressed, attracted, and repulsed by the exotic lifestyle of the rancheros. John Fremont’s expedition captured the city for the USA in 1846. The neat story about William Foxen leading him to the San Marcos Pass is repeated on a historical marker and in the WPA Guide, but the Santa Barbara historian Walker “Two Guns” Tompkins, who switched to history after writing a bunch of Westerns, says there’s no evidence of this. Imagine how remote Santa Barbara must’ve been from Mexico City by then.

In his Crown Journeys guide to New Orleans Roy Blount says,

I’ll bet I have been up in N. O. at every hour in every season

A good boast: he’s qualified.

I can’t make either claim about Santa Barbara. I suspect it’s pretty dead in the late to early hours. One day I’ll stay up all night and find out. Over about twenty years I have visited about 1.5 times a year.

On my first visits I found the town dramatic in geography but kinda sleepy. The big houses on the slopes were dramatic, and a wharf is always pleasing. If I stayed overnight I’d stay at one of the beach hotels and eat at Tupelo Junction or In n Out or La Super Rica, Julia Child’s favorite.

Long before many figured it out, [Julia Child] recognized that our pleasant climate, historical farming culture, and ranch-to-plate cuisine were conspiring together to elevate the American Riviera…

(source)

“The climate and the atmosphere [of Santa Barbara] recall the French Riviera between Marseille and Nice,” wrote Julia. “Very often, being there on the Riviera, where we used to have a little house, I’d… say, ‘Well, I’d just as soon be in Santa Barbara.’”

That from Edible Santa Barbara piece on JC. She actually lived in the next door woodsy microclimate of Montecito, which we’ll consider a separate topic.

Santa Barbara does have a touch of Julia Child about it: rich, pleasant, fancy, sorta stuffy? She retired there. A place to retire, if things went great.

But in the past few years on a couple visits to Santa Barbara I’ve seen two big changes that perk the place up, for the day tripper anyway. One is the Funk Zone Boom.

From a 2011 Santa Barbara Independent article on Funk Zone history by Ethan Stewart:

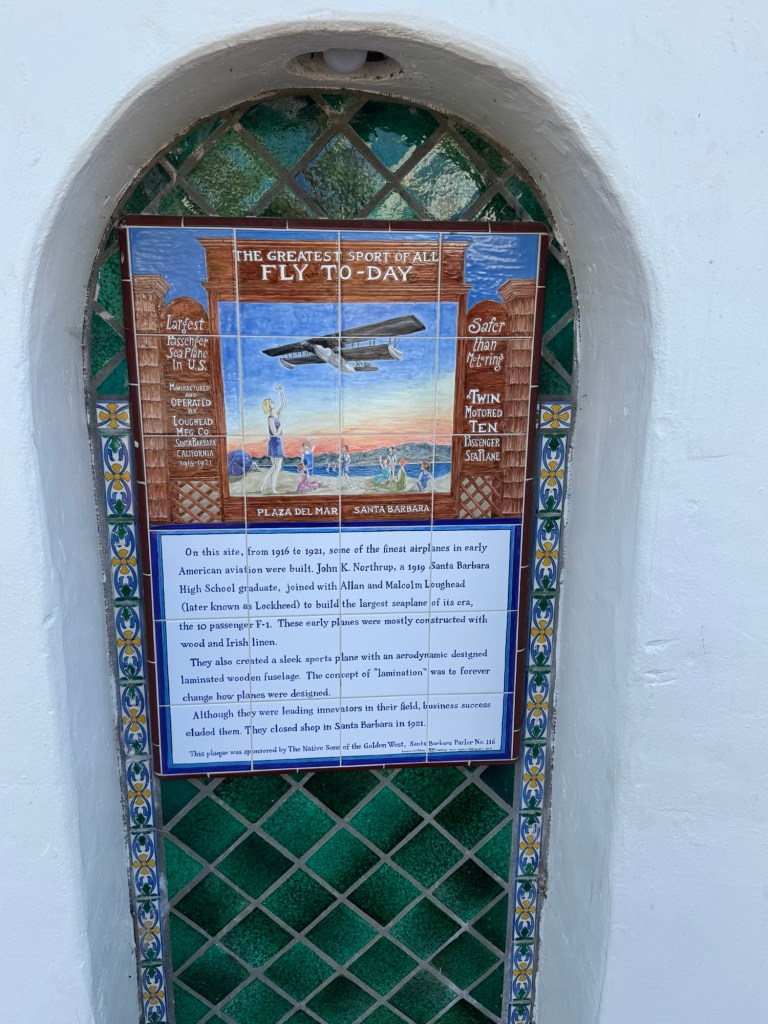

The Funk Zone was “funky” and functional long before the nickname was ever coined. In the mid 1900s and earlier, what we now call the Funk Zone was the industrial, marine, and manufacturing part of town. The Lockheed Corporation was born there, one of Santa Barbara’s first grain mills and feed stores was there (memorialized to this day by the tall, monolithic building at the ocean end of Gray Avenue), the Castagnolas used the area as ground zero for their fishing empire, and Radon Boats rose to prominence on Funk Zone soil, to name a few.

Activists, artists, and planners debated what to do with this area:

Controversial to this day, the city’s decision was ultimately to adopt a code that requires things in the Funk Zone to either be tourist-serving in nature, mixed-use residential/commercial units, or marine-oriented light manufacturing. In short, everything in the Funk Zone will eventually fall into one of these categories.

Fourteen years after that article, it appears that for better or worse the plan worked. The Funk Zone is less funky and strange than it used to be, and possibly worse for residents, especially those who don’t measure their riches in money. But for the tripper the Funk Zone is now full of wonderful places to consume. The multiple buildings of the Hotel Californian, mission style but built in 2025, dominate a block.

The other big change that perks up Santa Barbara came out of COVID: they closed down State Street to cars. Now there’s a walkable, bikeable avenue you can take from the wharf almost all the way to the mission.

Along the way you’ll pass some terrific buildings. Even the post office and the US Bankruptcy Court are magnificent.

Santa Barbara has progressed, yet in many respects the city of a hundred years ago foreshadowed the city of today. In 1842, Sir George Simpson, an English traveler, wrote: “Among the settlements, Santa Bárbara possessed the double advantage of being the oldest [sic] and the most aristocratic.” Few would rise to dispute that point today. The city still refrains from the commonplace. Her beaches and festivals never are vulgarized by catch-penny devices. Santa Barbara exemplifies the truth of the statement that life without beauty is but half lived.

Nowhere in the State has a higher standard been set and the achievements of this municipality are an incentive to city planners everywhere.

Santa Barbara is old. It was a native Canaliño village when the Spanish settled there, and as such, it was ancient even then. Superimposing European culture on the primitive Indian people was a hasty process, as historical time is reckoned. Where once existed the conical huts of the native Indians, now rise the urban structures of twentieth-century industry. Where once the campfires of Canaliños lighted the landscape at night, now blazing neon signs brighten the avenues of commerce. Where once natives stalked game in the underbrush, now chain-store clerks weigh out sliced meat behind delicatessen counters.

For Santa Barbara is as new as she is old. Preserving some of the most pleasant aspects of her Spanish traditions, reviving some of the customs of her earliest settlers, she is, nevertheless, as American as Council Bluffs, Iowa.

So says the 1941 WPA Guide to the city, which sums it up:

Santa Barbara’s chief business is simply being Santa Barbara.

Santa Barbara knew it had something special going on. The Harvard man turned California booster Charles Fletcher Lummis gave a speech, “Stand Fast Santa Barbara,” in 1923.

Beauty and sane sentiment are Good Business as well as good ethics. Carelessness, ugliness, blind materialism are Bad Business. The worst curse that could befall Santa Barbara would be the craze of GET BIG! Why big? Run down to Los Angeles for a few days — see that madhouse! You’d hate to live there!

…It is up to you to save Santa Barbara’s romance and save California’s romance for Santa Barbara. I would like to see Santa Barbara set her mark as the most beautiful, the most artistic, the most distinguished and the most famous little city on our Pacific Coast. It can be, if it will, for it has all the makings.“

Two years later, a big earthquake struck Santa Barbara:

The twin towers of Mission Santa Barbara collapsed, and eighty-five percent of the commercial buildings downtown were destroyed or badly damaged. A failed dam in the foothills released forty-five million gallons of water, and a gas company engineer became a hero when he shut off the city’s gas supply and prevented fires like those that destroyed San Francisco following the 1906 earthquake.

Perfect timing. The architects were ready: Lionel Pries, William Mooser, George Washington Smith. In the wake of the destruction the city’s Community Arts Association pushed the whole city to adopt rules for a unified architectural scheme. The strong willed Pearl Chase, born in Boston, seems like she was a key figure here. Chase Palm Park by the beach is named for her.

Pearl Chase: another Julia Child type?

If the earthquake had happened in 1915, or 1935, or 1945, I’m not sure the will would’ve been there to create such a Santa Fe-style strict code for unified building. Funny how history works out. Chance and random is absolutely an element, along with the forceful personalities. There’s a lesson here in never letting a good crisis go to waste. If there were a movement with a vision and a political will, LA could do something incredible with rebuilding Palisades and Altadena. Instead it seems we’re limping along directionless.

The result of the Santa Barbara revitalization is what you see and you see it everywhere. Santa Barbara is a theme park of itself. The Hotel Californian, where we stayed, was built in 2015, a new Funk Zone construction, but keeps to the white walls/red roof mission style aesthetic.

After lunch we tasted some wines at Kunin tasting room. Our pourer was knowledgable but not overbearing. He pointed out that Santa Barbara isn’t the biggest city in Santa Barbara County. That’s Santa Maria, with 109,987 residents. Santa Barbara, tucked in a corner of the county, has a mere 86,499, comparable to Elgin, Illinois or Newton, Massachusetts.

Santa Barbara isn’t very big, as California cities go. Here are some cities in California that have more people: Hemet, Manteca, Citrus Heights, Tracy, Norwalk, Hesperia, Rialto, Jurupa Valley, Menifee, Temecula, Thousand Oaks. Santa Barbara is #94 in the latest California city population rankings, just ahead of Lake Forest and Leandro. Think it’s fair to say that it punches above its weight in cultural resonance.

Santa Barbara County is vast: 2,745 square miles. If you smooshed down all the mountains and made it flat it would be even bigger. About a third of that is national forest. The population is small: 441,257 residents. Compare that to Norfolk County, MA, which has 727,473 over 441 square miles, and it doesn’t feel exactly crowded. Santa Barbara County thus is remote. Our wine server got to talking about the Santa Barbara Highlands region, where he said there are many beautiful vineyards, but no tasting rooms, and he recommended packing our own food.

After a siesta and a hot tub soak on the roof of the Californian, dinner was at Holdren’s. Cold martinis, cowboy steak, local red wine, brown leather booths, a classic. Pretty popping for a Tuesday. Sometime I’ll have to try the tasting menu at Barbareño, where the food is inspired by local history and tradition.

(Always funny to see a fishing boat leaving at like 9:15 am. Aren’t you supposed to be up at at ‘em?)

The next morning, after Helena Avenue Bakery (A+, bakery from a dream) treats we rode the janky hotel bikes up to the mission, just challenge enough along carless State Street with a brief residential detour. The ride’s uphill, revealing another feature of Santa Barbara. The city is tiled slightly to the south, opening to the ocean. This creates, in my opinion, the effect that Santa Barbara can seem “too sunny,” even though it has about the same number of sunny days as LA, and not infrequent Pacific fog. North of the equator the sun just hits harder when a place is south-facing.

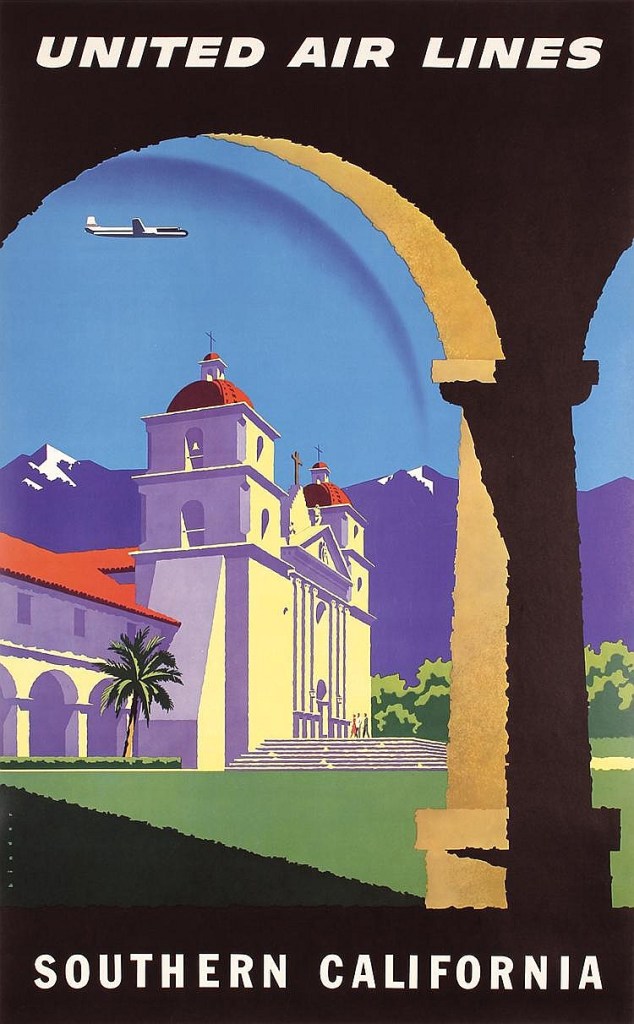

These days the mission and the mission period tends to be more associated with the word “genocide” and the crummy outcomes for Mission Indians rather than with romance and grandeur. It wasn’t that long ago they were a draw, consider this old United Airways poster:

That’s Queen of the Missions Santa Barbara right there, apparently circa 1952. These days I don’t think you sell California that way. “Old churches” are like the last thing you’d go see – you’re coming for Star Wars Land and $24 smoothies!

The rose garden is the star of the mission

and the old washing basin.

Then it’s downhill, along Garden Street, past the splendid five and six million dollar houses, maintained in style, and to Alice Keck Memorial Garden.

(Wikipedia’s Summerzz took that one.)

Alice Keck was the daughter of William Keck, a Daniel Plainview-grade oil man:

Starting as a penniless roustabout, he rose in the 1920s to found the Superior Oil Company. He pioneered deep offshore drilling, was first to find commercial deposits in the Gulf of Mexico, and practically ran the oil-rich nation of Venezuela. Even in his later years, when a drilling rig brought up a slimy core, old man Keck sniffed and tasted the rock to gauge the prospect.

another:

William Keck then became one of the first oilmen to move his business to Houston, which at the time was not much more than an inadequately drained malarial swamp… William Keck was known throughout the company he had created as “the Old Man”, and people called him that until the day he died. His character was strong and some said it was mean. His political views were fiercely conservative, but he was nimble and innovative when it came to doing business.

(sources for those. Who would guess a book about diamond spikes in the Canadian tundra would be quoted in an article about a California oil man?)

Mean or not, his name lives on in various charitable projects all over Southern California, like Keck Medicine at USC. His company Superior, was swallowed by Mobil which was swallowed by Exxon.

As you cruise down and look out over the water, you can still see oil wells in the Channel. Some of them are in various states of being dismantled, which is a whole project.

Both Northrop and Lockheed/Loughead were from here? Too big, topic for another day. Were I Pynchon I’d stop here and spend ten years on a 700 page novel about how Santa Barbara is a node of post-Cold War evil?

Before our return we scored some burritos for the train at IV Food Co-Op Downtown Market, and took some oysters and a dry white wine at Bluewater Grill. The server there, from Alabama, used to work in Taos, and gave me some ski reports from across the Rocky Mountain West. She seemed to be part of the class of lovely young people who turn up working at the affluent resort towns of the world. While in Bolivia I met a Chilean who said he’d spent a year in Santa Barbara. “What were you doing,” I asked, “studying?” “No,” he said, “just surfing and skating.” Santa Barbara seems like Heaven for that, if you can make the numbers math out. You’d probably have to live over in the student ghetto lands of Isla Vista, which is arguably a slum, but in a sorta student flophouse way. I have explored over there, though not on this trip, there is indeed something grim about it, but that’s not true Santa Barbara, and not what we’re talking about today.

Geneva’s the only person I know who grew up in Santa Barbara, and whatever she gets paid to write these days we can’t afford it! So we’ll have to do without firsthand accounts from native Santa Barbareños.

With that we were at the old Southern Pacific station for the 1:45pm Pacific Surfliner back to Los Angeles, refreshed and tired, energized and inspired.

This is just the daytripper’s view of Santa Barbara. Someone could make the case I’m missing “the real Santa Barbara,” I’m sure I am. There was a fatal stabbing there the other day, for example. But that’s not what I’m into. I’m after what makes Santa Barbara Santa Barbara. I want to put the place in context for myself, and for you, and to make those 25 hours last a little longer.

The Found Image Press finds these old postcards and reprints them, but without any context, or dates

* fictional

Very informative and fun. Thank you!