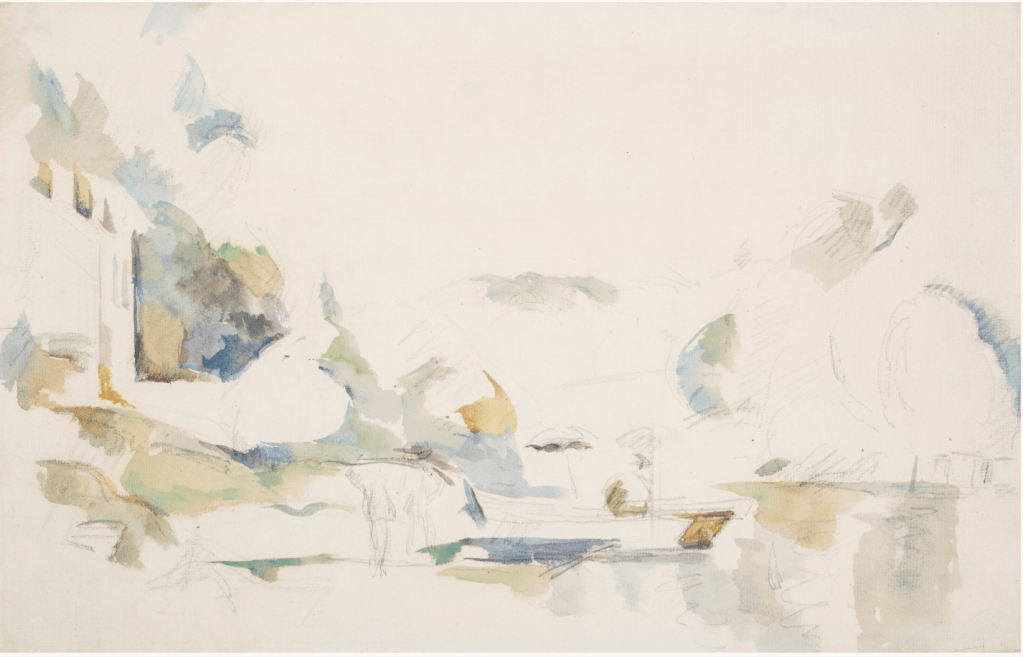

The Lac d’Annecy by Paul Cezanne

Posted: May 24, 2025 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

Cézanne painted this work while on holiday in the Haute-Savoie in 1896, writing dismissively of the conventional beauty of the landscape as “a little like we’ve been taught to see it in the albums of young lady travellers”. He rejected such conventions, seeking not to replicate the superficial appearance of the landscape but to express what he described as a “harmony parallel with nature” through a new language of painting.

In his essay “Cezanne’s Doubt” (mentioned by Jameson in Years of Theory) Maurice Merleau-Ponty says:

We live in the midst of man-made objects, among tools, in houses, streets, cities, and most of the time we see them only through the human actions which put them to use. We become used to thinking that all of this exists necessarily and unshakably. Cezanne’s painting suspends these habits of thought and reveals the base of inhuman nature upon which man has installed himself. This is why Cezanne’s people are strange, as if viewed by a creature of another species. Nature itself is stripped of the attributes which make it ready for animistic communions: there is no wind in the landscape, no movement on the Lac d’Annecy; the frozen objects hesitate as at the beginning of the world. It is an unfamiliar world in which one is uncomfortable and which forbids all human effusiveness. If one looks at the work of other painters after seeing Cezanne’s paintings, one feels somehow relaxed, just as conversations resumed after a period of mourning mask the absolute change and restore to the survivors their solidity. But indeed only a human being is capable of such a vision, which penetrates right to the root of things beneath the imposed order of humanity. All indications are that animals cannot look at things, cannot penetrate them in expectation of nothing but the truth. Emile Bernard’s statement that a realistic painter is only an ape is therefore precisely the opposite of the truth, and one sees how Cezanne was able to revive the classical

definition of art: man added to nature

Looking into Annecy by Cezanne I also find this, La Barque ou Le Lac d’Annecy, which Christie’s sold for $403,200 USD

Here’s an intriguing essay by Jeffrey Meyers on Hemingway and Cezanne. In several places Hemingway said he wanted to write like Cezanne painted:

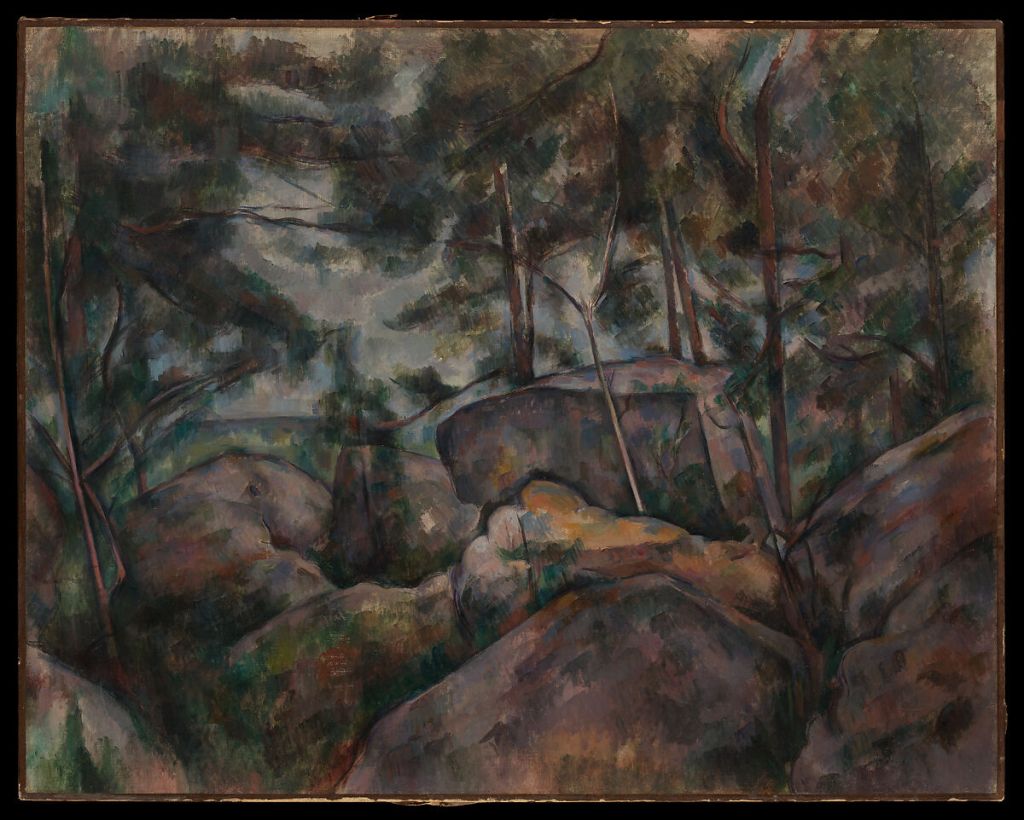

Hemingway spent several minutes looking at Cezanne’s “Rocks – Forest of Fontainebleu.” “This is what we try to do in writing, this and this, and the woods, and the rocks we have to climb over,” he said. “Cezanne is my painter, after the early painters. Wonder, wonder painter…

As we walked along, Hemingway said to me, “I can make a landscape like Mr. Paul Cezanne. I learned how to make a landscape from Mr. Paul Cezanne by walking through the Luxembourg Museum a thousand times with an empty gut, and I am pretty sure that if Mr. Paul was around, he would like the way I make them and be happy that I learned it from him.”

What does it mean to write like Cezanne painted? In his essay Merleau-Ponty quotes Cezanne in a way that gives a clue:

Nor did Cezanne neglect the physiognomy of objects and faces: he simply wanted to capture it emerging from the color. Painting a face “as an object” is not to strip it of its “thought.” “I agree that the painter must interpret it,” said Cezanne. “The painter is not an imbecile.” But this interpretation should not be a reflection distinct from the act of seeing. “If I paint all the little blues and all the little browns, I capture and convey his glance. Who gives a damn if they have any idea how one can sadden a mouth or make a cheek smile by wedding a shaded green to a red.” One’s personality is seen and grasped in one’s glance, which is, however, no more than a combination of colors. Other minds are given to us only as incarnate, as belonging to faces and gestures. Countering with the distinctions of soul and body, thought and vision is of no use here, for Cezanne returns to just that primordial experience from which these notions are derived and in which they are inseparable. The painter who conceptualizes and seeks the expression first misses the mystery— renewed every time we look at someone—of a person’s appearing in nature. In La peal de chagrin Balzac describes a “tablecloth white as a layer of fresh-fallen snow, upon which ,the place settings rose symmetrically, crowned with blond rolls.” “All through my youth,” said Cezanne, “I wanted to paint that, that tablecloth of fresh-fallen snow…. Now I know that one must only want to paint’rose, symmetrically, the place settings’ and ‘blond rolls.’ If I paint ‘crowned’ I’m done for, you understand? But if I really balance and shade my place settings and rolls as they are in nature, you can be sure the crowns, the snow and the whole shebang will be there.”

This effort did not make for an easy life for Cezanne:

Occasionally he would visit Paris, but when he ran into friends he would motion to them from a distance not to approach him. In 1903, after his pictures had begun to sell in Paris at twice the price of Monet’s and when young men like Joachim Gasquet and Emile Bernard came to see him and ask him questions, he unbent a little. But his fits of anger continued. (In Aix a child once hit him as he passed by; after that he could not bear any contact.)

…nine days out of ten all he saw around him was the wretchedness of his empirical life and of his unsuccessful attempts, the debris of an unknown celebrations

The closest Hemingway gets to saying something similar? Maybe it’s this, from an Esquire article, “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter,” October 1935, that’s in the form of a dialogue with an apprentice:

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise. Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Then get in somebody elseʼs head for a change If I bawl you out try to figure out what Iʼm thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Donʼt just think who is right. As a man things are as they should or shouldnʼt be. As a man you know who is right and who is wrong. You have to make decisions and enforce them. As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.

Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

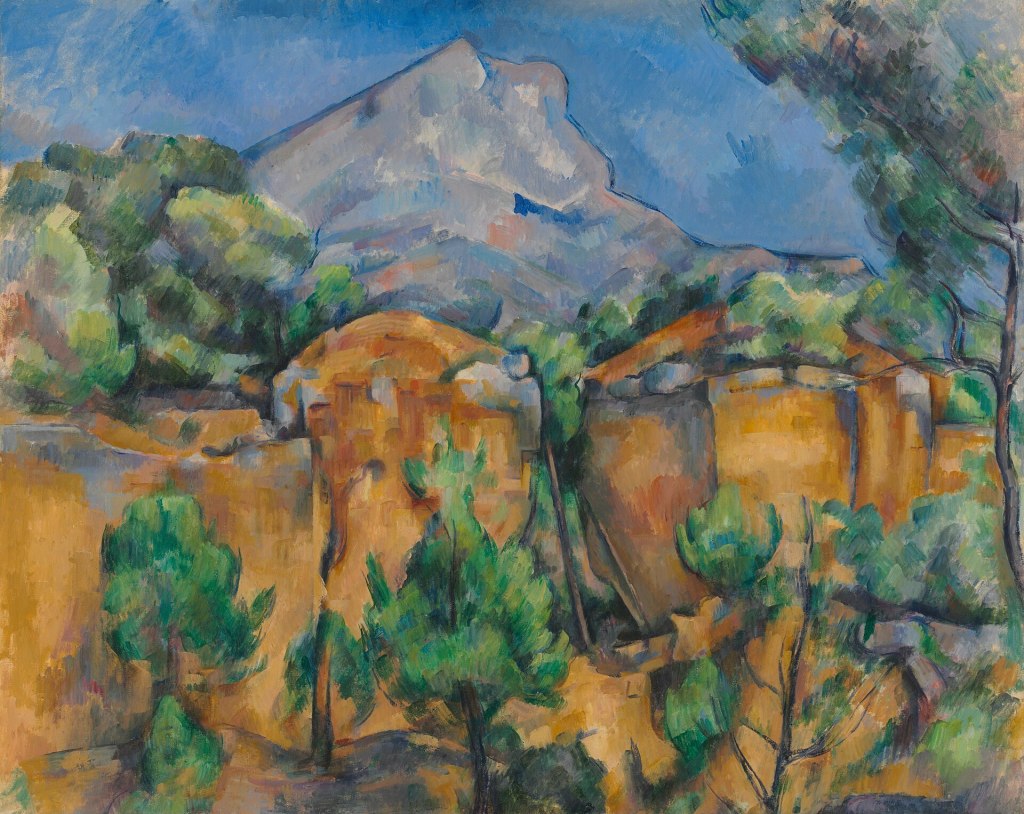

Cezanne left Annecy and went back to painting his Mont Saint-Victoire:

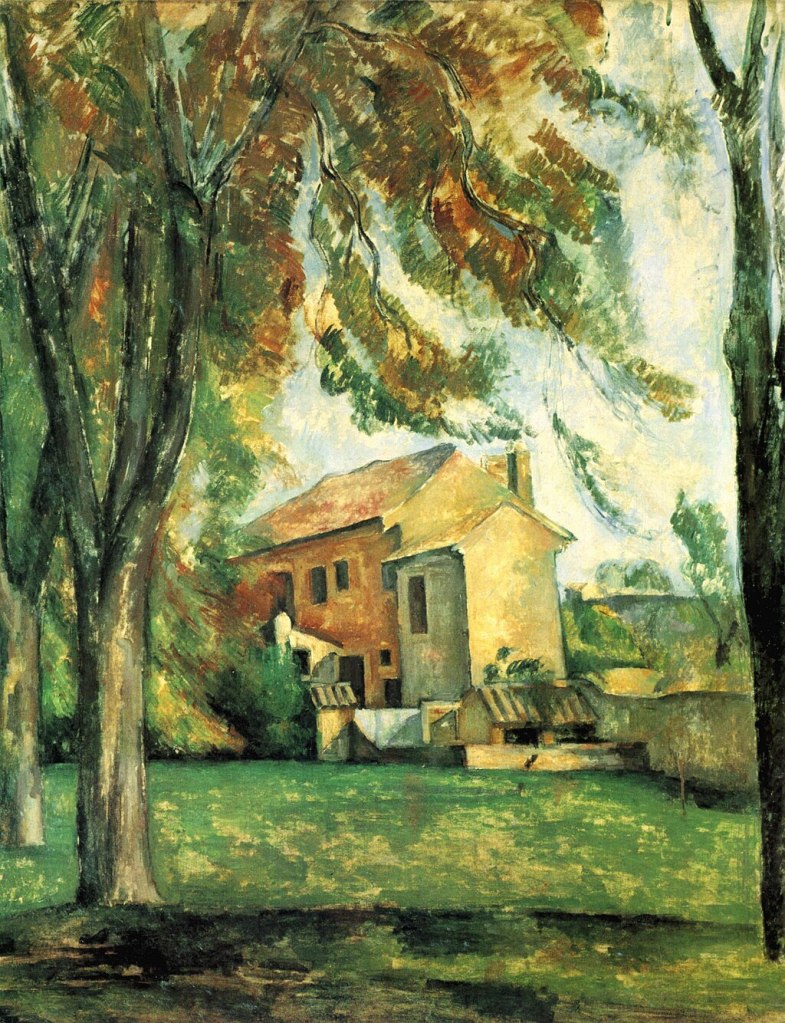

There are four Cezannes at the Norton Simon Museum, right down the street from where I’m typing this:

a couple at the Getty, one at the Hammer, and a classic at LACMA:

although that one’s not on display right now.

More on Cezanne.