MONIAC

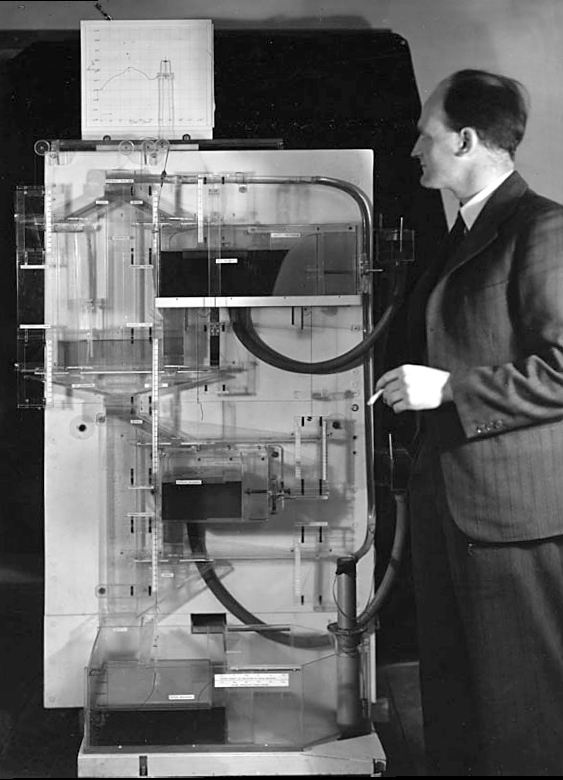

Posted: January 27, 2026 Filed under: money Leave a commentThere’s a visual metaphor for the process [of economists getting lost in models and trying to apply principles to reality] in the form of an amazing device called the Phillips machine, the creation of a remarkable New Zealander called Bill Phillips. After a roundabout route to the world of economics via a spell in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, Phillips set up a workshop in a south London garage. There, using recycled Lancaster bomber parts, he botched together a machine that used the flow of water to demonstrate the functioning of the entire British economy. There was a point at which these machines, known as MONIACs—Monetary National Income Analogue Computers—were all the rage: there are about twelve of them (no one knows exactly how many were built) in places as diverse as the central bank of Guatemala, the University of Melbourne, Erasmus University in Rotterdam, and Cambridge, England, which has the only one that works. The Phillips machines/MONIACs were fine-tuned to simulate different economic conditions: the New Zealand one, for instance, was set up to match the specific dynamics of the New Zealand economy.

That’s from How To Speak Money by John Lanchester.

(source)

Lanchester continues:

Phillips was a serious man, who partly on the basis of his machine became a professor of economics at LSE, and he had a serious specific concern in creating the MONIAC, to do with stabilizing demand inside the economy. And yet, it’s hard not to see his machine as a comic allegory of what’s called wrong in the model-making side of economics. It’s inherently comic in the way that a Roz Chast cartoon is inherently comic. The idea that this thing can simulate something as big and complicated as an entire economy—really? And yet, that’s what economic models set out to do all the time. The Federal Reserve and US Treasury are to this day reliant on models of exactly this sort; their models are built out of mathematics rather than out of bomber parts and water, but the underlying principles are the same. Credit flows and monetary supply, inflation rates and external shocks and trade imbalances and fluctuations in demand and tax changes are all modeled in an exactly analogous way.

(source, the cigarette is a great touch)

Phillips:

During this period he learned Chinese from other prisoners, repaired and miniaturised a secret radio, and fashioned a secret water boiler for tea which he hooked into the camp lighting system.[4] Sir Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop explained that Phillips’ radio maintained camp morale, and that if discovered, Phillips would have faced torture or even death.[7]