Machine Learning Learning

Posted: January 31, 2026 Filed under: America Since 1945 1 CommentA sense that the frontier is moving very very fast on what we crudely call “AI.” (A rare point of agreement with President Trump*. “artificial intelligence” is a bad name, I don’t like using it and look for alternatives.)

It reminds us of the explosive growth of Internet, it moved fast. Many of the fast movers thrived. I started college in 1999. That was the first time I had consistent Internet access that didn’t rely on a school lab or an AOL free trial with a 3.5 disk mailed to us. Some of the first bloggers – Andrew Sullivan, Matt Yglesisas – established themselves and stayed there. A sense of if you’re not keeping up you’re falling behind motivated me.

Maybe we should “run at it” as Bill Gurley advises. This stuff isn’t going away, we can mock it, complain about it, or try to figure out what it can do.

The only coding I’ve ever done was in BASIC, or making a text football game on my TI-83 during Statistics class. That was quite satisfying, but limited. During the pandemic, I asked a friend who’s sharp at coding – we’ll call him CC, Coding Chum – what “learn to code” would look like. He suggested we work on a specific project. I suggested a name generator that would scrape Wikipedia, gather real names, and randomly pair first and last names. CC gave me a series of Zoom tutorials where we worked on this in Python. My takeaway was that “learning to code” for me would take several years and I’d never be professional grade at it. I lacked the aptitude and motivation.

Along comes “vibe coding.” This is where you type, in words, what you want to happen, and a machine intelligence does the coding for you. I decided to try this using Claude Code.

The main points of friction for me were interacting with the Terminal on my Mac. I don’t even know how to enter command lines or anything on my computer. But Claude (regular, I’m paying for the $20 a month level) walked me through that, often with me sending it screenshots of error messages.

Once we got through that, and installed what I needed for Claude Code, we got to work. The Wikipedia project proved too daunting for Claude Code. So, we reduced the scale. What’s a pool of names?

How about everyone who ever played Major League Baseball? Famously one of the most recorded and compiled activities, surely there would be databases. I didn’t even tell Claude Code what databases to use, but it went to work, gathered the names of all the twenty something thousand people who ever played Major League Baseball and create a name generator that would pair random first and last names.

This took some coaching and debugging that took less than an hour. Here’s the result. It favors unique first names: common names like “Mike” are in there only once, so they come up the same number of times as say Kenshin or Alvis. But, it works. All told this took less than an hour.

The result I shared with CC, who within a few minutes created a revised version, you can select for 1920s names, limit by eras, etc. People who are good at coding will still be better at coding.

Yet for me, a person not good at coding, I could now do in minutes what once seemed like it would take a year’s worth of training and then much hacking away to accomplish.

The limits of Machine Learning are still funny. That was me asking Claude to find obscure works of microhistory published by academic presses. Despite me sending it up here, it did a pretty good job.

As Ben Affleck points out, as a writer it will generate at best average material, and average writing is, as writing, worthless. But that’s now. Who knows what’s coming? As information gatherer, as a research assistant, Machine Learning tools are already tremendous.

When I finished my vibe coding an excitement was paired with a small sadness. The only limit to what I could accomplish is my imagination. And… I couldn’t really think of much else.

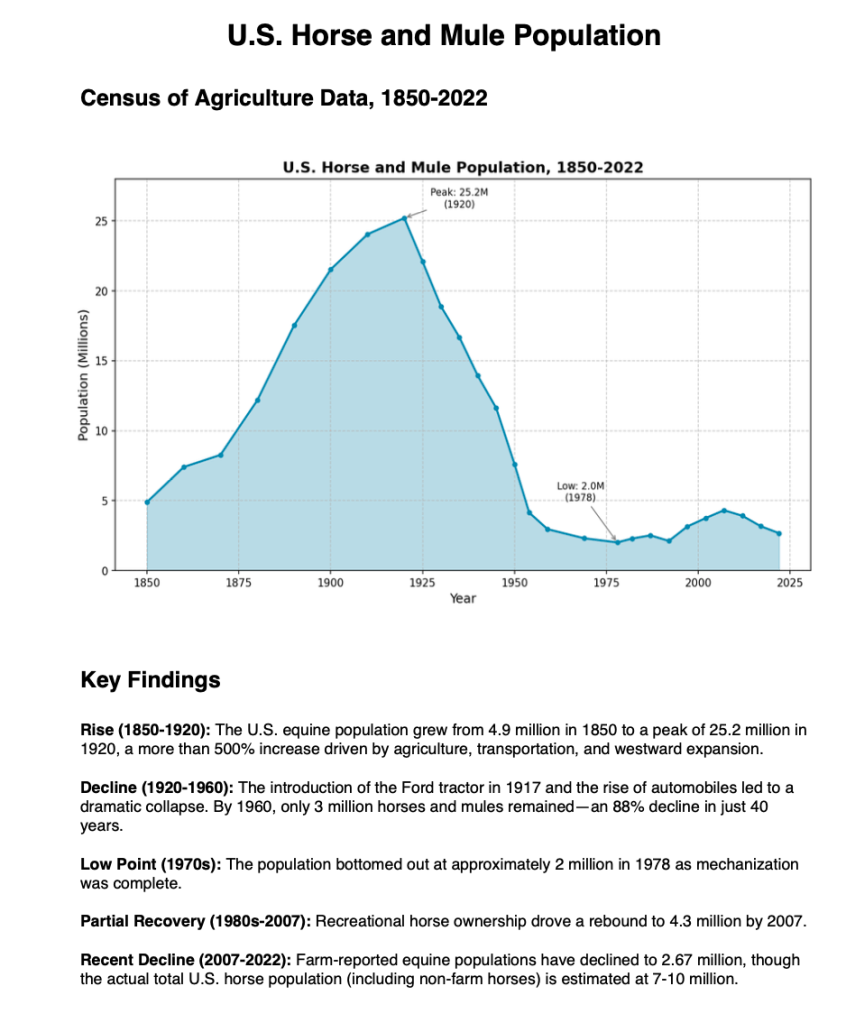

Someone on X suggested a powerful use is data visualization. I went to work. Here’s an example:

I asked Claude to go through Census data and create a chart of US horse and mule populations. I asked it to cite sources in MLA format:

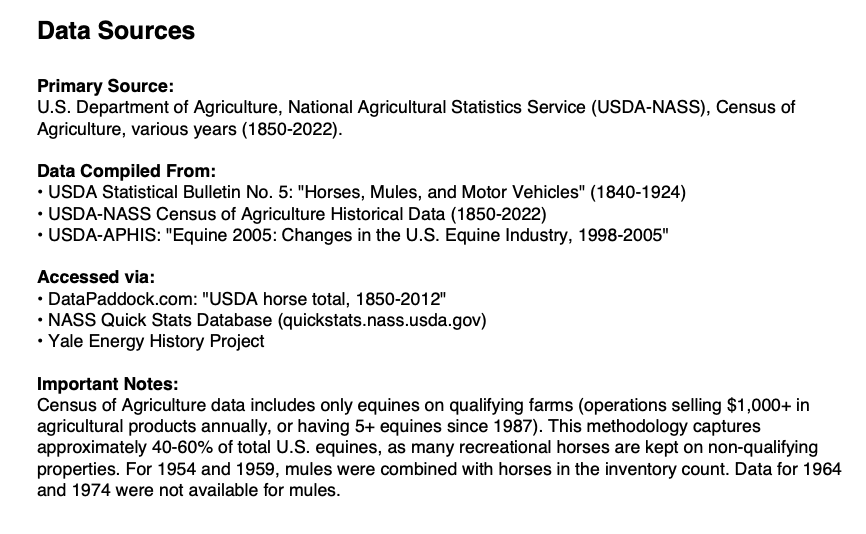

Here’s another:

This chart doesn’t show us much that’s new, such a chart may have even existed. These just happened to be some personal botherations I looked into. Work that would’ve taken an afternoon is done in seconds.

Extrapolate from here: what happens when we start putting this on archives, untranslated literatures? Historians have made careers on stuff like, for example, showing correlations between Salem land ownership and witchcraft allegations. If you start putting machines on archives, what connections will it find?

The hard part might be getting physical documents into the machines (which was a challenge for the witchcraft guys):

Published in 1978 in three volumes, The Salem Witchcraft Papers: Verbatim Transcripts of the Legal Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Outbreak of 1692 included transcriptions of the legal papers that had been done by a WPA team headed by Archie N. Frost in 1938, which had only been available to scholars in typescript form on deposit with the Essex Institute and with the Essex County Clerk of the Courts.

My belief is that the humanities will be slow to realize the effects these tools could have on their disciplines. By tomorrow you could have a silicon-based assistant who’s read everything extant in Latin and Greek. Or the entirety of the California Digital Newspaper Collection, or the Texas Slavery Project, or the Congressional Record. Here on my desk is a copy of Heart Of Europe: A History Of The Holy Roman Empire. Every paragraph seems to have something like “The Prussian King held only 4.5 percent of the agricultural land, with nobles owning and directly managing 11 per cent, and cities and foundations a further 4.5 percent.” Crunching that data might’ve been some historian’s summer. What kind of analysis will your computer assistant be able to do?

This assistant can read every language and find any pattern, and be trained to look for anything.

The job may scale up from doing the work to managing and steering the incredible power of the automated work-doers. We’ll all become managers. We’ll still have to figure out what to ask, of course.

It’s funny, I’m reminded of Shelby Foote:

I’ve never had anything resembling a secretary or a research assistant. I don’t want those. Each time I type, it gives me another shot at it, another look at it. As for research, I can’t begin to tell you the things I discovered while I was looking for something else. A research assistant couldn’t have done that. Not being a trained historian, I had botherations that led to good things. For instance, I didn’t take careful notes while reading. Then I’d get to something and I’d say, By golly, there’s something John Rawlins said at that time that’s real important. Where did I see it? Then I would remember that it was in a book with a red cover, close to the middle of the book, on the right-hand side and one third from the top of the page. So I’d spend an hour combing through all my red-bound books. I’d find it eventually, but I’d also find a great many other things in the course of the search.

There’s a lot to that. On the other hand, I remembered something like that quote, but I couldn’t remember where I found it. I thought maybe Shelby Foote? I told my troubles to two machine learned machines. Perplexity AI was stumped but Claude found it in seconds.

The future is hard to predict but we’re sitting on a volcano.

* still feels insane to type those words

I did some coding in a few classes in college, but I also lack the aptitude and motivation. Those are some great charts. I think I’m good at figuring out what questions to ask. Do you think it’s ok for Major League Baseball players to eat hot dogs in the dugout during games? – Tom Schreffler