John Dormandy’s Savoy

Posted: February 7, 2026 Filed under: Savoy Leave a commentSavoy was a small state – a principality, a dukedom, a kingdom – that covered parts of what’s now northwest Italy, Switzerland, and southeastern France. The borders were always shifting. For a time Savoy was its own country. The ruling family ended up as kings of Italy, until that ended shortly after World War Two. I’m interested in Savoy because I’ve twice been lucky to travel to the animation festival at Annecy, France, historically part of Savoy.

I judged this book by its cover, thought it might be kinda slop, and ignored it even though I have a strong interest in the history of Savoy. But after burning through most English language Savoy specific content, I bought and started reading it, and it’s fantastic! John Dormandy is a great, conversational, witty writer. He makes a great case for the importance of Savoy as a topic. Blessed with some clever rulers it managed to survive a long time while many other small states like Burgundy were swallowed up. Just an excerpt:

In 1858, Emperor Louis Napoleon III and Count Benzo Cavour, prime minister of King Victor Emmanuel, met secretly in the small spa town of Plombières in the Vosges mountains to hatch a plot. The two men, equally devious, agreed to provoke an attack by Austria on the Kingdom of Sardinia that included Savoy; the French would then promptly come to the aid of poor Sardinia, and together they would expel the Austrians from northern Italy. Following that happy outcome, Sardinia would acquire all of northern Italy and in recompense for his help, Napoleon III would be allowed to annexe Savoy to France. That was exactly what happened, except that by the mid-nineteenth century, Europe, particularly Victorian England, was beginning to baulk at countries being traded as commodities, especially if the recipient of the gift was France under a second Napoleon. Cavour and Napoleon, ever resourceful, organised a ‘free’ plebiscite in Savoy in which 99 per cent of the population voted for annexation to France.

I looked up John Dormandy, and sadly, he’s died. He wrote this book as a retirement project. He led a remarkable life. Here’s an edited version of an obituary I found here:

John Dormandy was born on 3 May 1937 in Budapest. He was the son of Paul Szeben, a pea grower who was accustomed to exporting his crop to the UK, and his wife Clara, who was an author and dramatist. He had a sister, Daisy, and his elder brother, Thomas, was to become a consultant chemical pathologist, renowned for his research on the actions of free radicals. The family were Jewish and went into hiding in 1944 when the Nazis invaded Hungary. After several months sheltering in a convent, they escaped to Geneva. In 1948 they made their way to London, where they settled and changed their surname to that of a village in Hungary which was 150 miles east of Budapest, where they had a country estate. John was educated in Hungary, Geneva and Paris before enrolling at London University to study medicine and graduating MB, BS in 1961. Apart from a spell as a registrar at the Royal Free, he was to spend most of his career at St George’s Hospital, progressing from lecturer in applied physiology to senior lecturer in surgery and, eventually, professor of vascular surgery.

He was famous for his pioneering work investigating the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases. A colleague referred to him as an unusual surgeon since he was keen to conserve affected limbs rather than to correct [the problem] immediately with a knife. Written with three co-authors, his book Clinical haemorheology (Springer, 1987) remains a standard work in the field. In the early 1990’s he was the first to advocate the use of specialist nurses to manage clinics for patients with chronic vascular disease and eventually this led to a nationwide network. He saw the benefits of multidisciplinary information sharing and was a leading figure in setting up the Trans-Atlantic Consensus for the management of peripheral artery disease (TASC) which published uniform guidelines in 2000. It was due to his personal involvement that so many vascular societies across Europe and North America collaborated in the research and adopted the recommendation. The author of five medical books and over 200 research papers, he continued to write and appear as an expert witness after his retirement in 2001.

In the 1980’s, as his fame grew, he was called upon to deal with some high profile patients. Flown to Baghdad, he operated on the varicose veins of Saddam Hussein’s mother, to be rewarded with a gold watch which was later stolen. In 1983 he went to Libya where he is thought to have treated either Colonel Gaddafi himself or one of his advisors. John was said to be extremely angry that the large bill for this was never paid due to the row over the siege of the Libyan Embassy the following year.

Due to his multicultural upbringing he was fluent in several languages. He was a popular and gregarious host, enjoying fine wines and good food often followed by a cigar. It was said that when he had to implement a no smoking policy as clinical director of St Georges he put a sign on his office door reading You are now leaving the premises of St George’s Hospital. A keen downhill skier, he also enjoyed playing golf and tennis and travelled at hair-raising speed round town on his beloved scooter. Other interests were art, architecture, theatre, opera and travelling – in retirement he published a book on his favourite part of France A history of Savoy: gatekeeper of the Alps (Fonthill, 2018).

His wife, Klara, predeceased him in December 2018 and he died suddenly in Paris on 26 April 2019. He was survived by his children Alexis and Xenia and stepchildren Gaby and Alex. His brother Thomas predeceased him in 2013.

What a guy! I feel like he’s a pal.

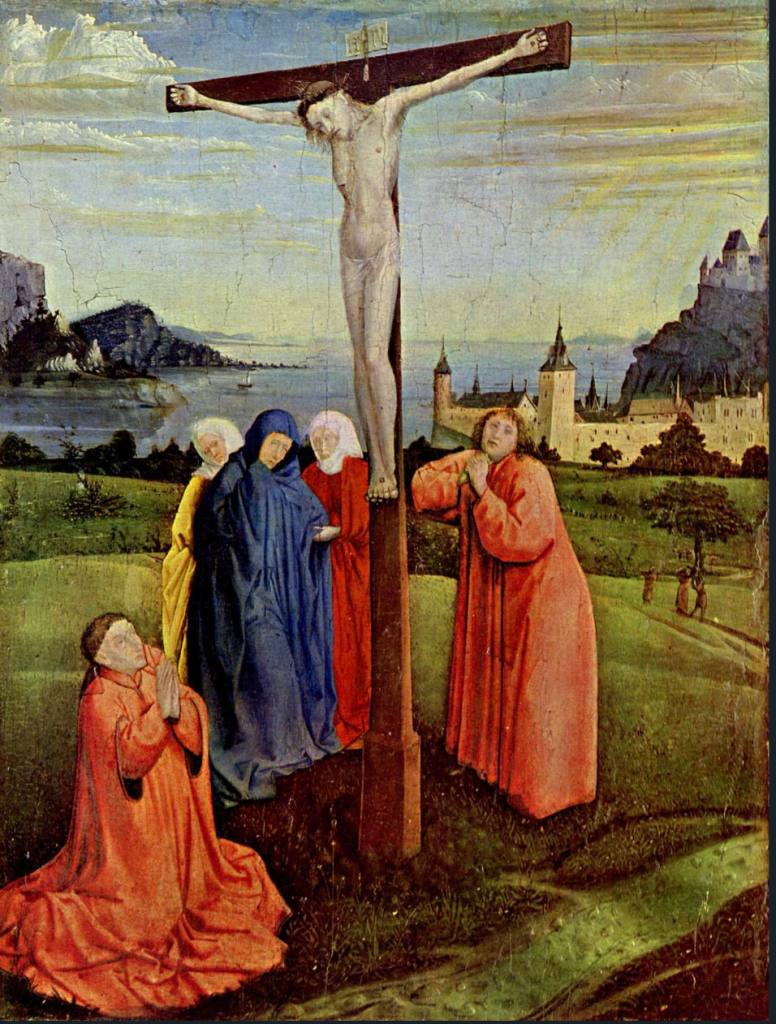

Dormandy thinks Konrad Witz’s Crucifixion depicts Annecy:

It does look like it. He also thinks Witz’s Miraculous Draught of Fishes depicts Lake Geneva, with Mont Blanc in the background, and that very much looks like it!: