Granger seen anew

Posted: June 18, 2025 Filed under: Texas, War of the Rebellion Leave a comment

With Juneteenth coming up we once again turn our thoughts to Gordon Granger. It was he who issued the famous General Order #3 at Galveston in 1865 (better late than never):

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.

The newly freed were slammed pretty fast into capitalism:

The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Geez, not even a small vacation?

We’ve covered Granger before – Grant didn’t like him. But in Charles Dana’s Recollections of the Civil War we came across some new (to us) material that brought the man to life:

After Chickamauga:

Our troops were as immovable as the rocks they stood on. Longstreet hurled against them repeatedly the dense columns which had routed Davis and Sheridan in the early afternoon, but every onset was repulsed with dreadful slaughter. Falling first on one and then another point of our lines, for hours the rebels vainly sought to break them. Thomas seemed to have filled every soldier with his own unconquerable firmness, and Granger, his hat torn by bullets, raged like a lion wherever the combat was hottest with the electrical courage of a Ney. When night fell, this body of heroes stood on the same ground they had occupied in the morning, their spirit unbroken, but their numbers greatly diminished.

Later, in the same campaign, Granger can’t stop firing a cannon personally:

The enemy kept firing shells at us, I remember, from the ridge opposite. They had got the range so well that the shells burst pretty near the top of the elevation where we were, and when we saw them coming we would duck-that is, everybody did except Generals Grant and Thomas and Gordon Granger. It was not according to their dignity to go down on their marrow bones. While we were there Granger got a cannon—how he got it I do not know-and he would load it with the help of one soldier and fire it himself over at the ridge. I recollect that Rawlins was very much disgusted at the guerilla operations of Granger, and induced Grant to order him to join his troops elsewhere.

As we thought we perceived, soon after noon, that the enemy had sent a great mass of their troops to crush Sherman, Grant gave orders at two o’clock for an assault upon the left of their lines; but owing to the fault of Granger, who was boyishly intent upon firing his gun instead of commanding his corps, Grant’s order was not transmitted to the division commanders until he repeated it an hour later.

He can’t stop driving Grant nuts:

The enemy was now divided. Bragg was flying toward Rome and Atlanta, and Longstreet was in East Tennessee besieging Burnside. Our victorious army was between them. The first thought was, of course, to relieve Burnside, and Grant ordered Granger with the Fourth Corps instantly forward to his aid, taking pains to write Granger a personal letter, explaining the exigencies of the case and the imperative need of energy.

It had no effect, however, in hastening the movement, and a day or two later Grant ordered Sherman to assume command of all the forces operating from the south to save Knoxville. Grant became imbued with a strong prejudice against Granger from this circumstance.

Mystery of the 27,574 muskets collected at Gettysburg

Posted: February 15, 2025 Filed under: War of the Rebellion, WOR Leave a comment

From Randall Collins, Violence: A Micro Sociological Theory. He’s speaking on firing rates among soldiers in wartime:

But the firing ratio in parade-ground formations was far from maximal. In American Civil War battles, 90 percent of muzzle-loading muskets collected after the battle of Gettysburg were found loaded, and half of those were multiply loaded, with two or more rounds on top of one another in the barre!

(Grossman 1995: 21-22); this implies that at least half the troops, at the moment they were hit or threw away their arms, had been repeatedly going through the motions of loading, but without actually firing, time after time. As we see later, casualties produced by these mass-formation troops were not high, and that could be attributed partly to non-firing, partly to inaccurate firing.

Collins thesis is that face to face violence is very hard for humans, it causes great stress and tension. In this section he’s arguing that even soldiers in battle have great difficulty shooting at each other, and often fire high or otherwise avoid shooting at each other. This detail got my attention, I wanted to know more. Collins source is David Grossman, On Killing. Grossman says:

Author of the Civil War Collector’s Encyopedia F. A. Lord tells us that after the Battle of Gettysburg, 27,574 muskets were recovered from the battlefield. Of these, nearly 90 percent (twenty-four thousand) were loaded. Twelve thousand of these loaded muskets were found to be loaded more than once, and six thousand of the multiply loaded weapons had from three to ten rounds loaded in the barrel. One weapon had been loaded twenty-three times. Why, then, were there so many loaded weapons available on the battlefield, and why did at least twelve thousand soldiers misload their weapons in combat?

A loaded weapon was a precious commodity on the black-powder battlefield. During the stand-up, face-to-face, short-range battles of this era a weapon should have been loaded for only a fraction of the time in battle. More than 95 percent of the time was spent in loading the weapon, and less than 5 percent in firing it. If most soldiers were desperately attempting to kill as quickly and efficiently as they could, then 95 percent should have been shot with an empty weapon in their hand, and any loaded, cocked, and primed weapon dropped on the battlefield would have been snatched up from wounded or dead comrades and fired.

There were many who were shot while charging the enemy or were casualties of artillery outside of musket range, and these individuals would never have had an opportunity to fire their weapons, but they hardly represent 95 percent of all casualties. If there is a desperate need in all soldiers to fire their weapon in combat, then many of these men should have died with an empty weapon. And as the ebb and flow of battle passed over these weapons, many of them should have been picked up and fired at the enemy.

The obvious conclusion is that most soldiers were not trying to kill the enemy. Most of them appear to have not even wanted to fire in the enemy’s general direction. As Marshall observed, most soldiers seem to have an inner resistance to firing their weapon in combat. The point here is that the resistance appears to have existed..

The amazing thing about these soldiers who failed to fire is the they did so in direct opposition to the mind-numbingly repetitive drills of that era. How, then, did these Civil War soldiers consistently “fail their drillmasters when it came to the all-important loading drill?

Some may argue that these multiple loads were simply mistakes, and that these weapons were discarded because they were misloaded. But if in the fog of war, despite all the endless hours of training, you do accidentally double-load a musket, you shoot it anyway, and the first load simply pushes out the second load. In the rare event that the weapon is actually jammed or nonfunctional in some manner, you simply drop it and pick up another. But that is not what happened here, and the question we have to ask ourselves is, Why was firing the only step that was skipped? How could at least twelve thousand men from both sides and all units make the exact same mistake?

Did twelve thousand soldiers at Gettysburg, dazed and confused by the shock of battle, accidentally double-load their weapons, and then were all twelve thousand of them killed before they could fire these weapons? Or did all twelve thousand of them discard these weapons for some reason and then pick up others? In some cases their powder may have been wet (even through their oiled-paper coating), but that many? And why did six thousand more go on to load their weapons yet again, and still not fire? Some may have been mistakes, and some may have been caused by bad powder, but I believe that the only possible explanation for the vast majority of these incidents is the same factor that prevented 80 to 85 percent of World War II soldiers from firing at the enemy. The fact that these Civil War soldiers overcame their powerful conditioning to fire through drill clearly demonstrates the impact of powerful instinctive forces and supreme acts of moral will…

Griffith’s figures make perfect sense if during these wars, as in World War Il, only a small percentage of the musketeers in a regimental firing line were actually attempting to shoot at the enemy while the rest stood bravely in line firing above the enemies’ heads or did not fire at all.

Well now hang on.

Let’s start with, how do we know this? What’s our source? This statistic on the 27,574 muskets, where do we get that?

I don’t have a copy of The Civil War Collector’s Encyclopedia handy. But luckily, with all questions related to the American Civil War, you can find the answer on some forum or another, which led me to this article, citing a source from 1867:

It seems strange to me that you would ship loaded weapons from Gettsyburg to Washington. Wouldn’t that be dangerous? Or maybe they weren’t likely to go off without the percussion cap? I’m not expert on Civil War firearms and don’t intend to become one. Still, the mystery puzzled me. Wouldn’t most of these weapons be kinda fucked up from being knocked around and exploded and so on? What does it tell us about the firing or non-firing of soldiers during the battle? Maybe these weapons were loaded and their unlucky holders were knocked out of action before they could be used?

A source the forum posters frequently point to is Paddy Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War. Paddy Griffith was an English scholar: here is a lovely obituary of him, he died in 2010.

Large, convivial yet dedicated to the serious analysis of military history, Paddy Griffith was a fearless challenger of the accepted versions of events and an iconoclastic war-gamer.

The absolute extremes of research in military history matters are often reached by war gamers and amateurs of various sorts. If you try and get to the ultimate authority on Civil War gunboats, for instance, you’ll end up being directed to The Western Rivers Steamboat Cyclopoedium, which is really a set of plans for model builders.

Anyway Griffith’s book arrived, and it’s excellent.

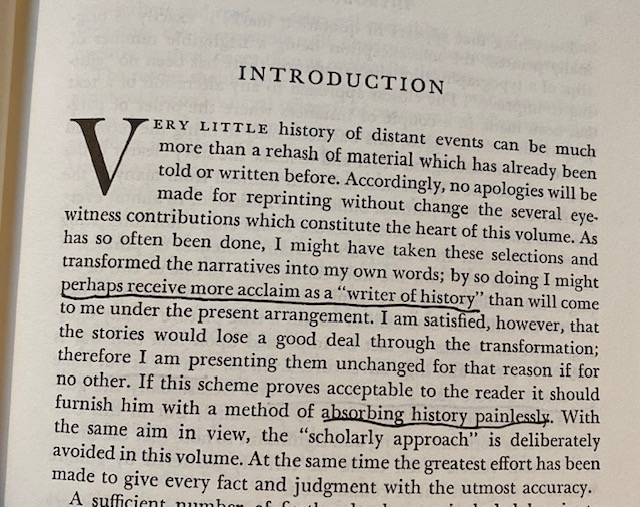

Vividly written, profound, a tremendous aid to understanding the Civil War in every way, from how troops carried their stuff and trained and spent their time to the macro history of the war, full of detail and extracts from memoirs and history. From the preface:

The past, of course, is a foreign country, and every historian is to some extent a tourist looking in from the outside upon the people and events he describes. In my own case, I have an added perspective as a British citizen who has literally been a tourist to many of the battlefields on which the Civil War was fought…

Both the tourist and the historian have a duty to be clear about their motives, especially in a case like the Civil War which remains important in modern-day life…

The experience of attaining military age also seems to have left me with another legacy, for like many another before me I became fascinated to discover just what a battle is, or was, like – preferably without actually venturing into one in person. I suspect that this somewhat unhealthy obsession is really quite common among military historians, and it can even be seen as a precondition of their calling. Each generation has had its own group of military writers who have wished to see the elephant of warfare without getting too close to it, and then relay their findings faithfully and truly to their readers.

It so happens that one of the most successful of all attempts to see the elephant in a war book was made in a novel about the American Civil War – about the battle of Chancellorsville, to be precise. This was of course Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, first published in 1894 when the author was only twenty-three years of age. It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this work to the general development of war writing, since its influence has been enormous and its perceptions remain as fresh and vigorous today as when they were originally penned. The amateur elephant watcher is especially captivated by what Crane had to say, and is led on inevitably into a closer examination of the Civil War battles. There is a sense in which Crane has consecrated these particular combats for every student of battles. I, for one, freely acknowledge my debt to him in much of what follows…

For the student of Napoleonic tactics, accustomed to a thin and insubstantial diet of secondary sources and unreliable data, the Civil War comes as a severe shock to the metabolism. It provides an unexpectedly rich feast of detailed personal memoirs, a cornucopia of fine regimental histories, and a solid dessert of circumstantial after-action reports. The student may gorge himself on these delicacies until he can move no more, yet still find that he has barely scraped the surface of what is on offer. In this respect, at least, the Civil War can indeed be seen as the first modern war. The spread of education and the desire to record personal experiences on paper is here exponentially greater than anything seen in Napoleonic times, even among Wellington’s endlessly scribbling light infantry. This wealth of first-hand evidence, furthermore, has been lovingly preserved and sifted by succeeding generations in a manner that puts modern Napoleonic studies to shame. Civil War history remains a living subject today, whereas Napoleonic analysis was all but killed off in 1914.° Indeed, this qualitative difference between the way the two eras have been studied may perhaps have helped to conceal their essential underlying unity.

Whereas the Napoleonic campaigns have been subconsciously relegated to a distant past, those of the Civil War are still being discovered in all their freshness from primary sources – lending them an air of modernity that may be subtly misleading.

There’s a touch of Bill James to Paddy Griffith’s passion. His book illuminated the War of the Rebellion for me in many ways. Among other things, it’s often pretty funny. You find this in the Civil War literature. Sam Watkins is very funny, even as he’s describing stumbling near-barefoot from disaster to disaster. Here’s Griffith describing a battle situation:

By 1864 it seems that there were numerous cases of combat refusal when an attack on fortifications was proposed. Even if this did not lead to a formal mutiny it could often lead to an ‘attack’ which went to ground almost before it had crossed its start line. The abortive ‘battle’ of Mine Run was an example of this on the grandest possible scale, since the entire Army of the Potomac came into position to storm Lee’s works but then thought better of it and went home.

The action of 35th Massachusetts at Spotsylvania provides a good example of how the 1864 fighting must often have been conducted. The regiment advanced behind another unit until it came under fire, when a bounty-jumper shouted ‘Retreat!’ and the whole regiment routed in panic. They rallied calmly when they had regained their own earthworks, insulted their new general (whom they did not recognise), then advanced again to a position in open ground one hundred yards from the enemy entrenchments. “Then the whole line lay down, without firing a shot, and in this position calmly sustained the fire of the enemy two or three hours, with little loss to us as the shells and bullets of the Confederates passed over our heads. The order was simply to ‘feel the enemy’, and as it was plain they were ready to receive us, no final assault was ordered.”

And that’s from their own regimental history! (Company I of the 35th Massachusetts was made up of men from Dedham, Needham and Weston, incidentally).

This decline to really get after it battlewise would seem well in line with Collins’ thesis, that people will do almost anything to avoid face to face violence. Griffith mentions many cases where individuals preferred to joke around or share supplies when they were supposed to be killing each other. On the other hand, Griffith describes plenty of situations where the two sides really did just stand there and blast away at each other at close range until one side couldn’t take it. As Shelby Foote says (discussing naval battles), it’s almost unbelievable, but they did it!

The amazing things about naval engagements are the accounts of men firing eight-inch guns at each other from a range of eight-feet. I’m afraid that is beyond my understanding. But they did it all the time in naval battles. It was a very strange business.

Let’s return to the matter of the collected muskets from Gettysburg. Here’s what Griffith says

An often quoted set of statistics from Gettysburg has it that the Union forces salvaged 27,574 ‘muskets’ after the battle, of which 24,000 were loaded, including 12,000 loaded twice, 6,000 loaded between three and ten times, one with twenty-three charges and one with twenty-two balls and sixty-six buckshot. Some had six balls and only one charge of powder; others had six unopened cartridges. Others again had the ball behind the powder instead of the other way round.

It is open to doubt whether twenty-three full cartridges could in fact be physically squeezed into the barrel of a Civil War rifle, and still more dubious that the proportion of misloaded weapons in the sample (some 45 per cent) actually reflects the proportion in the whole of the two armies during combat. It is most likely that many of the guns salvaged by the Union forces after Gettysburg were discarded by their users precisely because they had become unusable, hence the figure of 12,000 should be seen as a proportion of the total muskets in the battle rather than of the total salvaged. That suggests that perhaps 9 per cent of all muskets were misloaded – a less dramatic figure, but nevertheless still very significant. If we add the unknown total of misloaded muskets which were either salvaged by the Confederates or retained by their original owners, we are forced back to the conclusion that a very high proportion of infantry weapons must indeed have become inoperative in combat due to faulty handling.

Thus, it seems like these extra-loaded muskets weren’t unshot because their holders didn’t want to, contra Collins and Grossman. It was because they were busted.

A Civil War battle like any battle was totally chaotic and loud; Griffith’s book is largely about the problems of dealing with chaos, confusion, missed communication, strange terrain, and how people handled or failed to handle these challenges effectively. How to approach the truth of what happened in such a situation is an endless puzzle. Trying to get as close as possible to the source in this case has proved interesting. Griffith got as close as we’re likely to get, here are his sources:

My guy was tracking down unpublished doctoral theses to make his war games as accurate as possible. Despite the somewhat grim subject matter (guys blasting away at each other) learning about Griffith has uplifted my feelings about human nature and the power of curiousity. For those without any particular passion for the subject Griffith’s cover illustration probably tells you everything you need to know about a Civil War battle, although ironically no source is listed beyond “Cover Design by Maggie Mellett”.

Hopper’s America, discussing that painting, Dawn at Gettysburg:

Hopper himself relayed a story, told to him by a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, about Albert Einstein’s viewing of ‘Dawn Before Gettysburg’ in a show at MoMA.

‘Einstein in going through the galleries had stopped a long time before this picture of mine,’ Hopper said, ‘and I suppose it was his hatred of war that prompted him to do this as these men were evidently all ready for the slaughter.’

It’s easy to see why this little painting has made such an impact over the years. The colors are breathtaking, in particular the blood red of the dawn sky.

The individual soldiers are just that: individuals. As Warner points out, one has a blister on his foot from marching. Another has just vomited and is leaning on his friend, deathly ill. A standing soldier is getting orders ready, representing duty to his country.

I’ll have to discuss these matters with my uncle Dan next time I see him, he lives quite close to the battlefield. As we’ve discussed before Civil War battlefields can be very peaceful and pleasant to visit. They tend to be preserved farm and pastureland. It’s nice to be in a field.

(Previous coverage of Gettysburg, and the War of the Rebellion in general).

Conversations with Grant

Posted: September 7, 2024 Filed under: the California Condition, War of the Rebellion Leave a comment

After his Presidency Ulysses Grant took an around the world tour with his wife and the diplomat, librarian and scholar John Russell Young, who took notes on the trip and published them in a book.

The trip as recorded by Young is interesting but much of it was written for an audience that would never travel overseas. It was a ponderous, two-volume tome of over 1,300 pages with 800 engraved illustrations.

The good folks at Big Byte Press have taken the juiciest parts and compiled them into Conversations With Grant. (Note that this version does not include the famous conversation with Bismarck). I could spend a while with their various reprints of historical memoirs for Kindle. What a service. Here are some items we learn:

after the end of the Civil War, Grant wanted to keep going and invade Mexico:

“When our war ended,” said General Grant, “I urged upon President Johnson an immediate invasion of Mexico. I am not sure whether I wrote him or not, but I pressed the matter frequently upon Mr. Johnson and Mr. Seward [Secretary of State, William Seward]. You see, Napoleon in Mexico was really a part, and an active part, of the rebellion. His army was as much opposed to us as that of Kirby Smith. Even apart from his desire to establish a monarchy, and overthrow a friendly republic, against which every loyal American revolted, there was the active co-operation between the French and the rebels on the Rio Grande which made it an act of war. I believed then, and I believe now, that we had a just cause of war with Maximilian, and with Napoleon if he supported him—with Napoleon especially, as he was the head of the whole business. We were so placed that we were bound to fight him. I sent Sheridan off to the Rio Grande. I sent him post haste, not giving him time to participate in the farewell review. My plan was to give him a corps, have him cross the Rio Grande, join Juarez, and attack Maximilian. With his corps he could have walked over Mexico. Mr. Johnson seemed to favor my plan, but Mr. Seward was opposed, and his opposition was decisive.” The remark was made that such a move necessarily meant a war with France. “I suppose so,” said the General. “But with the army that we had on both sides at the close of the war, what did we care for Napoleon? Unless Napoleon surrendered his Mexican project, I was for fighting Napoleon. There never was a more just cause for war than what Napoleon gave us. With our army we could do as we pleased. We had a victorious army, trained in four years of war, and we had the whole South to recruit from. I had that in my mind when I proposed the advance on Mexico. I wanted to employ and occupy the Southern army. We had destroyed the career of many of them at home, and I wanted them to go to Mexico. I am not sure now that I was sound in that conclusion. I have thought that their devotion to slavery and their familiarity with the institution would have led them to introduce slavery, or something like it, into Mexico, which would have been a calamity. Still, my plan at the time was to induce the Southern troops to go to Mexico, to go as soldiers under Sheridan, and remain as settlers. I was especially anxious that Kirby Smith with his command should go over. Kirby Smith had not surrendered, and I was not sure that he would not give us trouble before surrendering. Mexico seemed an outlet for the disappointed and dangerous elements in the South, elements brave and warlike and energetic enough, and with their share of the best qualities of the Anglo-Saxon character, but irreconcilable in their hostility to the Union. As our people had saved the Union and meant to keep it, and manage it as we liked, and not as they liked, it seemed to me that the best place for our defeated friends was Mexico. It was better for them and better for us. I tried to make Lee think so when he surrendered. They would have done perhaps as great a work in Mexico as has been done in California.” It was suggested that Mr. Seward’s objection to attack Napoleon was his dread of another war. The General said: “No one dreaded war more than I did. I had more than I wanted. But the war would have been national, and we could have united both sections under one flag. The good results accruing from that would in themselves have compensated for another war, even if it had come, and such a war as it must have been under Sheridan and his army—short, quick, decisive, and assuredly triumphant. We could have marched from the Rio Grande to Mexico without a serious battle.

although he thought the first Mexican War was bad:

I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral courage enough to resign.

…The Mexicans are a good people. They live on little and work hard. They suffer from the influence of the Church, which, while I was in Mexico at least, was as bad as could be. The Mexicans were good soldiers, but badly commanded. The country is rich, and if the people could be assured a good government, they would prosper. See what we have made of Texas and California—empires. There are the same materials for new empires in Mexico.

on Napoleon:

Of course the first emperor was a great genius, but one of the most selfish and cruel men in history. Outside of his military skill I do not see a redeeming trait in his character. He abused France for his own ends, and brought incredible disasters upon his country to gratify his selfish ambition I do not think any genius can excuse a crime like that.

He never wanted to go to West Point, or be in the army at all:

was never more delighted at anything,” said the General, “than the close of the war. I never liked service in the army—not as a young officer. I did not want to go to West Point. My appointment was an accident, and my father had to use his authority to make me go. If I could have escaped West Point without bringing myself into disgrace at home, I would have done so. I remember about the time I entered the academy there were debates in Congress over a proposal to abolish West Point. I used to look over the papers, and read the Congress reports with eagerness, to see the progress the bill made, and hoping to hear that the school had been abolished, and that I could go home to my father without being in disgrace. I never went into a battle willingly or with enthusiasm. I was always glad when a battle was over. I never want to command another army. I take no interest in armies. When the Duke of Cambridge asked me to review his troops at Aldershott I told his Royal Highness that the one thing I never wanted to see again was a military parade. When I resigned from the army and went to a farm I was happy.

The Battle of St. Louis was narrowly avoided:

there was some splendid work done in Missouri, and especially in St. Louis, in the earliest days of the war, which people have now almost forgotten. If St. Louis had been captured by the rebels it would have made a vast difference in our war. It would have been a terrible task to have recaptured St. Louis—one of the most difficult that could be given to any military man. Instead of a campaign before Vicksburg, it would have been a campaign before St. Louis.

He loved Oakland, and Yosemite:

The San Francisco that he had known in the early days had vanished, and even the aspect of nature had changed; for the resolute men who are building the metropolis of the Pacific have absorbed the waters and torn down the hills to make their way.

…

Oakland is a suburb of San Francisco, and is certainly one of the most beautiful cities I have seen in my journey around the world.

…

So much has been written about the Yosemite that I venture but one remark: that having seen most of the sights that attract travelers in India, Asia, and Europe, it stands unparalleled as a rapturous vision of beauty and splendor.

He wanted to live in California:

The only promotion that I ever rejoiced in was when I was made major-general in the regular army. I was happy over that, because it made me the junior major-general, and I hoped, when the war was over, that I could live in California. I had been yearning for the opportunity to return to California, and I saw it in that promotion. When I was given a higher command, I was sorry, because it involved a residence in Washington, which, at that time, of all places in the country I disliked, and it dissolved my hopes of a return to the Pacific coast. I came to like Washington, however, when I knew it.

He had some reservations about Lee as a general:

Lee was of a slow, conservative, cautious nature, without imagination or humor, always the same, with grave dignity. I never could see in his achievements what justifies his reputation. The illusion that nothing but heavy odds beat him will not stand the ultimate light of history. I know it is not true. Lee was a good deal of a headquarters general; a desk general, from what I can hear, and from what his officers say. He was almost too old for active service—the best service in the field. At the time of the surrender he was fifty-eight or fifty-nine and I was forty-three. His officers used to say that he posed himself, that he was retiring and exclusive, and that his headquarters were difficult of access. I remember when the commissioners came through our lines to treat, just before the surrender, that one of them remarked on the great difference between our headquarters and Lee’s. I always kept open house at head-quarters, so far as the army was concerned.

On Shiloh:

“No battle,” said General Grant on one occasion, “has been more discussed than Shiloh-none in my career. The correspondents and papers at the time all said that Shiloh was a surprise-that our men were killed over their coffee, and so on.

There was no surprise about it, except,” said the General, with a smile, “perhaps to the newspaper correspondents. We had been skirmishing for two days before we were attacked. At night, when but a small portion of Buell’s army had crossed to the west bank of the Tennessee River, I was so well satisfied with the result, and so certain that I would beat Beauregard, even without Buell’s aid, that I went in person to each division commander and ordered an advance along the line at four in the morning. Shiloh was one of the most important battles in the war. It was there that our Western soldiers first met the enemy in a pitched battle. From that day they never feared to fight the enemy, and never went into action without feeling sure they would win. Shiloh broke the prestige of the Southern Confederacy so far as our Western army was con-cerned. Sherman was the hero of Shiloh.

He really commanded two divisions-his own and McClernand’s-and proved himself to be a consummate soldier. Nothing could be finer than his work at Shiloh, and yet Shiloh was belittled by our Northern people so that many people look at it as a defeat.

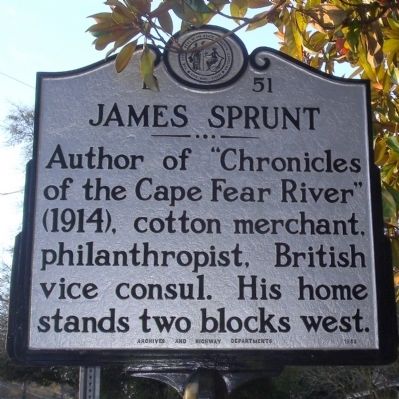

Chronicles of the Cape Fear River

Posted: May 14, 2024 Filed under: north carolina, War of the Rebellion Leave a comment

Speaking of chronicles, and Wilmington, you can’t visit Wilmington, North Carolina without hearing about this one.

Since we got a copy we’ve been meaning to write it up but it’s a bit daunting. It runs to about 700 pages.

One excerpt will suffice.

Sprunt had a nice house:

and was this cottage his as well?:

The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion

Posted: April 19, 2024 Filed under: War of the Rebellion 1 CommentThe first time I went to look at the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion at the LA Public Library (Central, Geneaology and History Department) the librarian said “it’s… it’s a lot” and then he showed them to me:

Before the Civil War was even over they’d started compiling the official records: every report and bit of correspondence they could gather.

Some of it is dull, and some of it is very vivid:

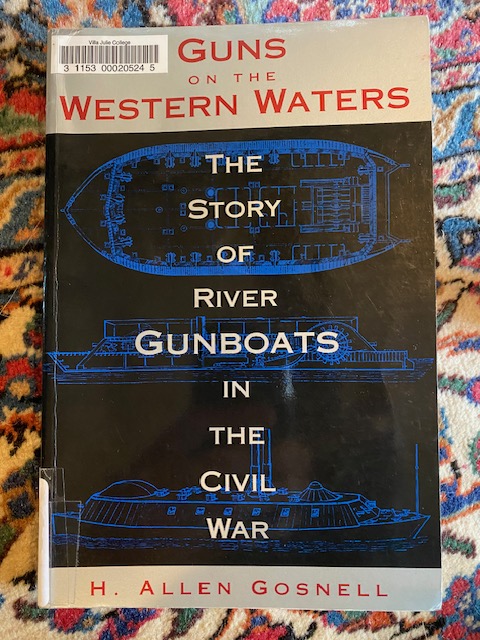

Guns on the Western Waters, H. Allen Gosnell

Posted: April 6, 2024 Filed under: War of the Rebellion 1 Comment

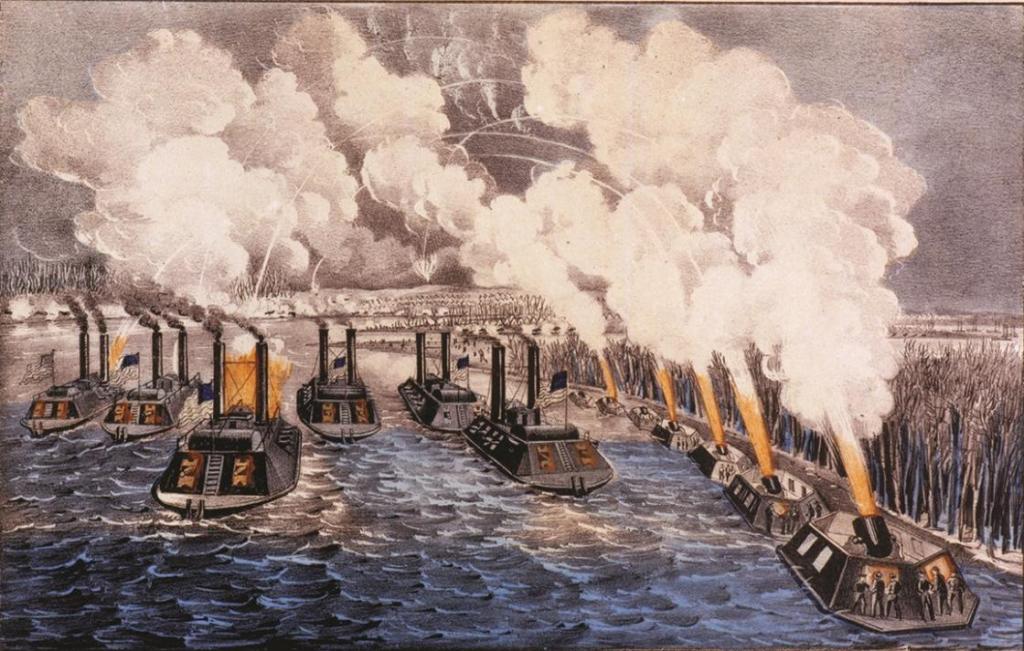

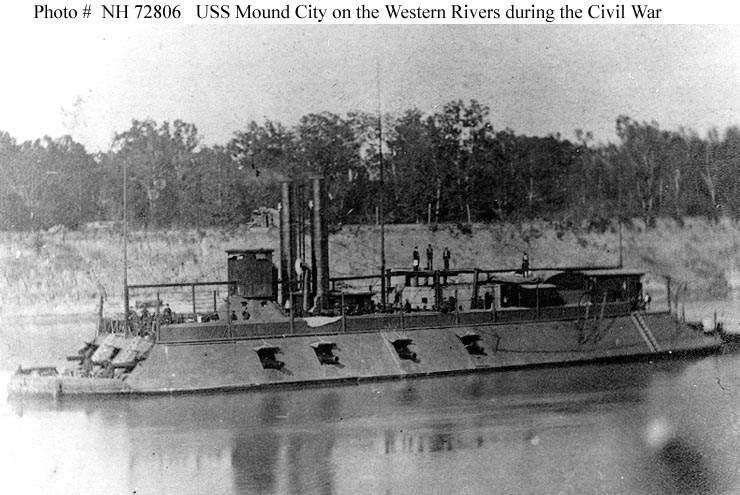

Can you imagine seeing this in color? Fire in the darkness reflecting on the flowing water? The sounds?

Ulysses Grant, who heard the screams of the wounded at Shiloh, Cold Harbor, the Wilderness, a hundred other battlefields, uses the word “sickening” only twice in his Personal Memoirs: once to describe a bullfight he saw in Mexico, and once to describe “the sight of the mangled and dying men which met my eye as I boarded” the USS Benton, a steamship, after a battle on the Mississippi River off Grand Gulf, Louisiana.

It’s incredible. The amazing things about naval engagements are the accounts of men firing eight-inch guns at each other from a range of eight-feet. I’m afraid that is beyond my understanding. But they did it all the time in naval battles. It was a very strange business.

So said Shelby Foote in a Naval Institute Proceedings interview. In that same interview:

Naval History: Many regimental histories were written for Army units in the Civil War. Why was that apparently not the case for the Navy?

Foote: I really don’t know. No big Navy man even wrote his memoirs, did he? Guns on the Western Waters was one of my main sources. And I use the naval Official Records. But I have found a shortage of naval material.

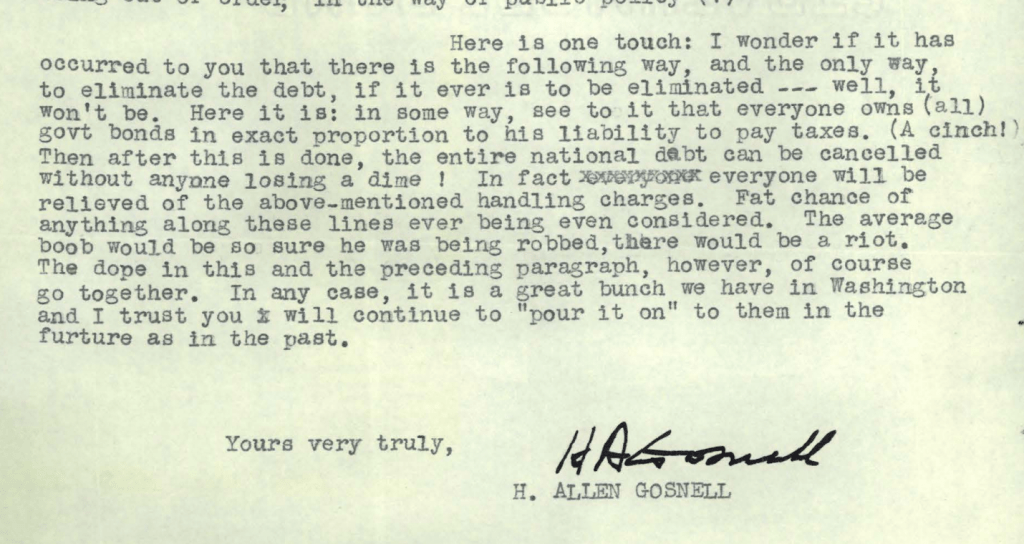

I got so much value out of this book, which I bought used via Amazon. Gosnell was a Lt. Commander in the Navy Reserve. I can find little else about him except possibly this letter?:

Anyway his book is terrific. Here’s how it begins:

The book is indeed mostly firsthand accounts of the river battles along the Mississippi during the War of the Rebellion (fka Civil War).

It’s arguable that all the drama with Lee in Virginia was just a sideshow/violent pageant, that the real war was won and the rebellion ended when the Union seized the Mississippi from New Orleans to Illinois, slicing the Confederacy in half. This was finished by July 4, 1863. When it was done the guy who did it, Grant, was brought east to mop up the operations there.

The best section of Guns On the Western Waters is David Dixon Porter’s story of an expedition along the Yazoo River backwaters, and what he encountered there. Next best is Junius Henri Browne’s tale of a night in a boat passing under the guns of Vicksburg, from his Four Years in Secessia. Gosnell says he’s sometimes edited accounts to make them less graphic, but guys are still trampling around in their shipmate’s brains. These battles were infernal, boilers would explode scalding people, if they didn’t write their memoirs maybe it’s because it was too intense to think about, plus half of them were dead.

When Grant heard that Junius Henri Browne and his fellow “Bohemians” (a gang of war correspondents who don’t seem super likable) were lost this is what he said:

An unsung hero of this era is James Buchanan Eads

who was contracted to construct the City Class ironclads for the war on the Mississippi, and built seven in five months.

The Union was just superior to the Confederacy in building, technology, mechanizing. Arguably Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory did the best he could with a challenging situation, and for that he has a nice square named after himself at Key West. But throughout the war we just find a more effective machine destroying a feebler competitor.

Eads has a bridge named after him near St. Louis. I said unsung earlier but I guess he’s reasonably sung. And how about his wife, Martha Dillon Eads?:

Shelby on Shiloh (and more)

Posted: November 18, 2023 Filed under: War of the Rebellion Leave a comment

Naval History: I know that the Battle of Shiloh is near and dear to your heart. Why is that?

Foote: For one things, the Shiloh battlefield is within 100 miles of me. The other reason is even better. Shiloh is, to my mind, unquestionably the best-preserved Civil War battlefield of them all.

It has been singularly fortunate in many ways. It’s not so close to a large city or populated area, so it is not clogged with tourists all the time. But the main thing is, it has had only five or six superintendents, I believe, and each one has been thoroughly conscious to keep the place the way it was when the battle was fought. It’s not surrounded by hot dog stands the way Gettysburg is. In the Official Records Pat Cleburne’s report of the attack on what had been [Major General William T.] Sherman’s headquarters describes going through a blackjack thicket and then across marshy ground and up a hill. You can go there today, and the blackjack thicket, the marshy ground, and the hill are still there. It’s a beautiful experience.

Shelby Foote interviewed by the Naval Institute Press in 1994.

on the blockade:

The blockade, tenuous and penetrable as it was, still had an enormous effect on little things. Nobody really knows the effect the blockade had on the people of the Confederacy.

The rarity of little items that you don’t ordinarily think of was hugely important. They didn’t have needles for sewing; they had to improvise thorns to use for needles. They didn’t have nails to repair their ramshackle houses. By the time the war was over, after four years of being without nails, half the houses in the South were being shaken to pieces. Things like that you don’t normally think about, but the North’s naval blockade caused it.

how about this:

Naval History: As much as any other historians, you and David McCullough are responsible recently for popularizing history, as opposed to doing formal academic studies.

Foote: Yeah.

More:

What I’m calling young historians are people at least in their 40s or 50s. You have to reach that age before you have enough life experience to be a historian. I don’t think you can have a 22-year-old historian. You can have a 22-year-old mathematical genius. You can have a 22-year-old poet. But I doubt you can have a 22-year-old historian.

Contemplating possible transition to historian, in my 50s.

(Shelby’s views on the Confederate flag seem less clear, to me)

Was the US Civil War fueled by lack of athletic contests?

Posted: September 24, 2023 Filed under: War of the Rebellion 1 Comment

that from:

It sounds crazy but Bruce Catton knew Civil War veterans.

The big early Civil War battles were probably the largest gatherings in American history up to that time. The biggest tent revival meeting was probably 1/10 the size of Shiloh. Something big was finally happening. Shelby Foote speaks on this as well.

Is history driven as much as anything by the desire to “make history”?