Carter’s, congealed electricity, AI and Needham

Posted: January 30, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, children, New England, Uncategorized Leave a comment

If you have a little kid in the US you will have some clothes from Carter’s. They sell them at Target and Wal-Mart as well as 1,000 or so Carter’s stores, and they cost $8.

Before I had a kid it didn’t occur to me that kids outgrow their clothes so fast they can’t cost too much.

When I see the Carter’s label, I think of my home town.

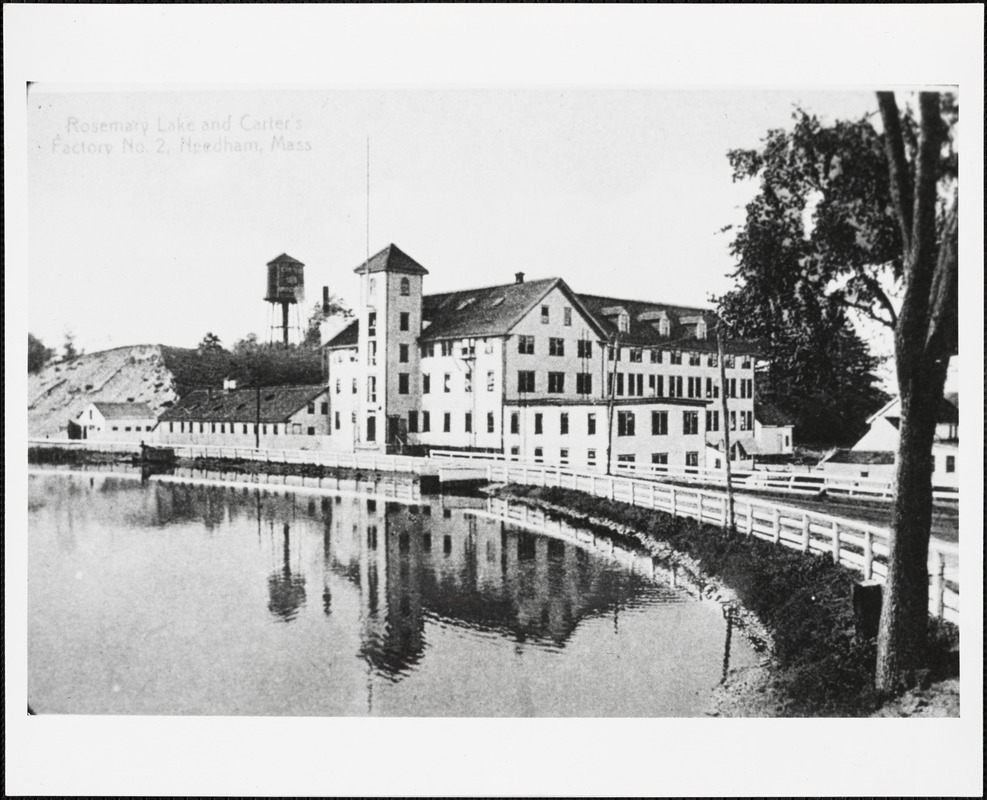

William Carter founded Carter’s in Needham, Massachusetts in 1865. Textiles were a big business in New England. Two inputs, labor and electricity, were cheap. Labor from excess farm children, and electricity from running streams? That would’ve been the earliest mode, what were they using by 1865? Coal?

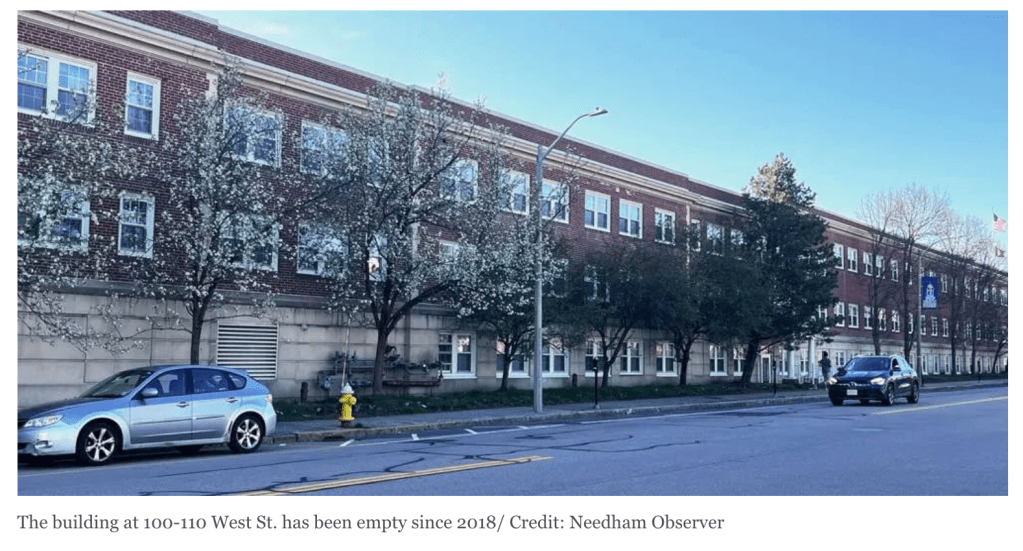

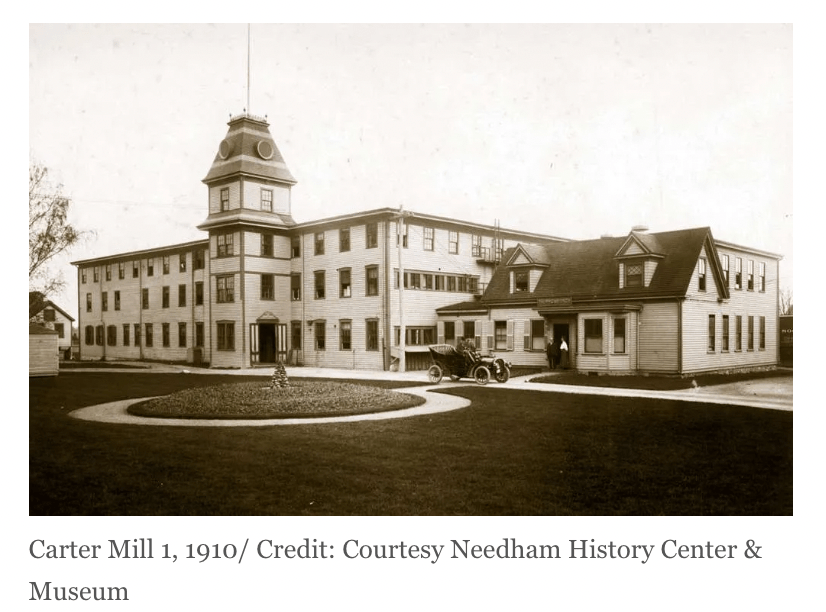

One of the biggest buildings in Needham, certainly the longest, is the former Carter’s headquarters, which stretches itself along Highland Avenue. A prominent landmark, it took a long time to walk past.

The story of Carter’s is a global economic story in miniature.

Old Carter mill #2, found here.

The Carter family sold the company in the 1990s. It went public in 2003. In 2005, Carter’s acquired OshKosh B’gosh, a company famous for making children’s overalls. This company started in 1895 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin (the name comes from an Ojibwe word, “The Claw,” that was the name of a local chief).

The term “B’gosh” began being used in 1911, after general manager William Pollock heard the tagline “Oshkosh B’Gosh” in a vaudeville routine in New York.[4] The company formally adopted the name OshKosh B’gosh in 1937.

OshKosh B’Gosh’s Wisconsin plant was closed in 1997. Downsizing of domestic operations and massive outsourcing and manufacturing at Mexican and Honduran subsidiaries saw the domestic manufacturing share drop below 10 percent by the year 2000.

OshKosh B’Gosh was sold to Carter’s, another clothing manufacturer for $312 million

The headquarters of Carter’s moved to Atlanta. Labor and electricity were cheaper in Georgia, Carter’s had been opening mills in the South for awhile. Now the clothes are made overseas. I look at the labels on Carter’s clothes: Bangladesh, India, Cambodia, Vietnam. If you factor in the shipping and the markup how much of that $8 is going to your garment maker in Bangladesh? Then again maybe it’s the best job around, raising Bangladeshis out of poverty, and soon Chittagong will look like Needham.

The former Carter’s headquarters, now vacant, became a facility for elder living. My mom worked there, briefly. Carter’s today is headquarted in the Phipps Tower in Buckhead, Atlanta, which I happened to pass by the other day.

The loss of the mill and the company headquarters was not a crisis for Needham. Needham is very close to Boston, an easy train ride away, and along of the 128 Corridor. There are growth businesses in the area, hospitals, biotech companies, universities. TripAdvisor is based in Needham. Needham is a pleasant town, there are ongoing talks to turn the former Carter’s building into housing. It would be close to public transport and walkable to the library and the Trader Joe’s. That seems to be stalled.

Needham has brain jobs, attached to a dense brain network, while brawn jobs are being shipped overseas. There are many other towns in Massachusetts where the old run down mill is a sad derelict as production moved first south and then overseas. These towns are bleak. Oshkosh, Wisconsin seems ok, but the shipping of steady jobs overseas is of course a major factor in our politics, Ross Perot was talking about it in 1992 and no one did anything about it and now Trump is the president.

A similar story lies in the history of Berkshire Hathaway – the original New Bedford textile mill, not the conglomerate Warren Buffett built on top of it using the same name. Buffett talks about this, I believe this is from the 2022 annual meeting:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I remember when you had a textile mill —

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, god.

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and it couldn’t —

WARREN BUFFETT: I try to forget it. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and the textiles are really just congealed electricity, the way modern technology works.

And the TVA rates were 60% lower than the rates in New England. It was an absolutely hopeless hand, and you had the sense to fold it.

WARREN BUFFETT: Twenty-five years later, yeah. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, you didn’t pour more money into it.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, that’s right.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And, no — recognizing reality, when it’s really awful, and taking appropriate action, just involves, often, just the most elementary good sense.

How in the hell can you run a textile mill in New England when your competitors are paying way lower power rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: And I’ll tell you another problem with it, too. I mean, the fellow that I put in to run it was a really good guy. I mean, he was 100% honest with me in every way. And he was a decent human being, and he knew textiles.

And if he’d been a jerk, it would have been a lot easier. I would have probably thought differently about it.

But we just stumbled along for a while. And then, you know, we got lucky that Jack Ringwalt decided to sell his insurance company [National Indemnity] and we did this and that.

But I even bought a second textile company in New Hampshire, I mean, I don’t know how many — seven or eight years later.

I’m going to talk some about dumb decisions, maybe after lunch we’ll do it a little.

Congealed electricity, what a phrase. In the 1985 annual letter, Buffett discusses the other input, labor, which was cheaper in the South, and why he kept Berkshire Hathaway running in Massachusetts anyway:

At the time we made our purchase, southern textile plants – largely non-union – were believed to have an important competitive advantage. Most northern textile operations had closed and many people thought we would liquidate our business as well.

We felt, however, that the business would be run much betterby a long-time employee whom. we immediately selected to be president, Ken Chace. In this respect we were 100% correct: Ken

and his recent successor, Garry Morrison, have been excellent managers, every bit the equal of managers at our more profitable businesses.… the domestic textile industry operates in a commodity business, competing in a world market in which substantial excess capacity exists. Much of the trouble we experienced was attributable, both directly and indirectly, to competition from foreign countries whose workers are paid a small fraction of the U.S. minimum wage. But that in no way means that our labor force deserves any blame for our closing. In fact, in comparison with employees of American industry generally, our workers were poorly paid, as has been the case throughout the textile business. In contract negotiations, union leaders and members were sensitive to our disadvantageous cost position and did not push for unrealistic wage increases or unproductive work practices. To the contrary, they tried just as hard as we did to keep us competitive. Even during our liquidation period they performed superbly. (Ironically, we would have been better off financially if our union had behaved unreasonably some years ago; we then would have recognized the impossible future that we faced, promptly closed down, and avoided significant future losses.)

Buffett goes on, if you care to read it, to discuss the dismal spiral faced by another New England textile company, Burlington.

Charlie Munger, in his 1994 USC talk, spoke on the paradoxes here:

For example, when we were in the textile business, which is a terrible commodity business, we were making low-end textiles—which are a real commodity product. And one day, the people came to Warren and said, ‘They’ve invented a new loom that we think will do twice as much work as our old ones.’

And Warren said, ‘Gee, I hope this doesn’t work because if it does, I’m going to close the mill.’ And he meant it.

What was he thinking? He was thinking, ‘It’s a lousy business. We’re earning substandard returns and keeping it open just to be nice to the elderly workers. But we’re not going to put huge amounts of new capital into a lousy business.’

And he knew that the huge productivity increases that would come from a better machine introduced into the production of a commodity product would all go to the benefit of the buyers of the textiles. Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.

That’s such an obvious concept—that there are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Is something similar happening with AI? Who will it make rich, and at what cost? To whose ribs will the profits stick?

I’m not sure we could call AI congealed but it is more or less just more and more electricity run through expensive processors. Who will win from that? So far it’s been the makers of the processors, but if DeepSeek shows you don’t need as many of those the game is changed. Personally I’m unimpressed with DeepSeek – try asking it what happened in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

How does Carter’s itself continue to survive? Target’s own brand, Cat & Jack, is right next door on the shelves. Could another company shove Carter’s aside if they can cut the margins even thinner, get the price down to $7? Here’s what Carter’s CEO Michael Casey has to say in their most recent annual letter:

Hard to build the operational network Carter’s has over 150+ years. There will be a challenge awaiting the next CEO of Carter’s as Michael Casey is retiring. Carter’s stock ($CRI) is pretty beaten up over the past year, down 30%. A possible macro problem for Carter’s is that the number of births in the United States appears to be declining.

It is powerful, when I’m changing my daughter, to contemplate my home town, and global commerce, and the people in Cambodia who made these clothes, and the ways of the world.