Steinbeck on the two Christmases

Posted: December 22, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, Steinbeck, the California Condition Leave a commentWriting about the quiz show scandal in The Fifties, David Halberstam says:

It was a traumatic moment for the country as well. Charles Van Doren had become the symbol of the best America had to offer. Some commentators wrote of the quiz shows as the end of American innocence. Starting with World War Two, they said, America had been on the right side: Its politicians and generals did not lie, and the Americans had trusted what was written in their newspapers and, later, broadcast over the airwaves. That it all ended abruptly because one unusually attractive young man was caught up in something seedy and outside his control was dubious. But some saw the beginning of the disintegration of the moral tissue of America, in all of this. Certainly, many Americans who would have rejected a role in being part of a rigged quiz show if the price was $64 would have had to think a long time if the price was $125,000. John Steinbeck was so outraged that he wrote an angry letter to Adlai Stevenson that was reprinted in The New Republic and caused a considerable stir at the time. Under the title “Have We Gone Soft?” he raged, “If I wanted to destroy a nation I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy, and sick … on all levels, American society is rigged…. I am troubled by the cynical immorality of my country. It cannot survive on this basis.”

This isn’t quite accurate, as far as I can tell – “Have We Gone Soft?” was an article by the Jesuit Thurston N. Davis, included as part of a larger symposium, in the February 15, 1960 New Republic, you can read it here. No matter.

Steinbeck’s phrase or the rough idea of it stuck with me since I read The Fifties back in high school (in Frank Guerra’s class, American Since ’45, the best class in my high school (we used to call it “Guerra Since ’45” since a lot of it was Coach Guerra’s personal memories of era, which were terrific and much appreciated, as Frank Guerra was one of the most charismatic teachers at the school and the head football coach. We’re straying)).

The other day I realized I had a copy of Steinbeck’s letters on my shelf. It might have the quoted letter in it.

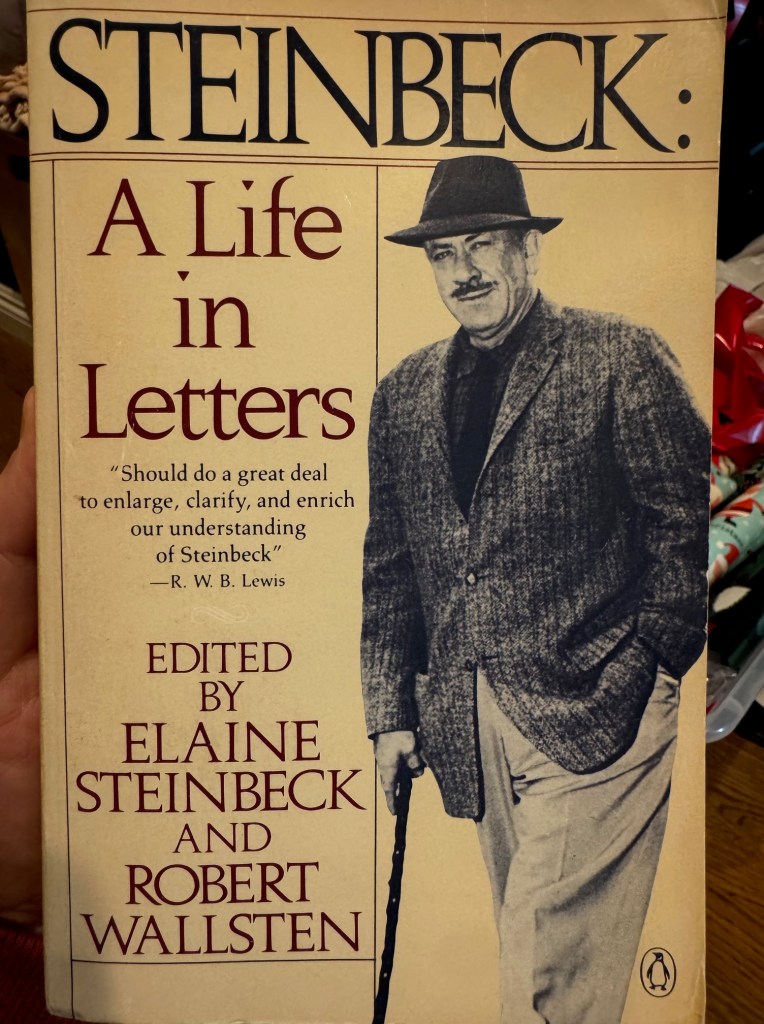

On the cover Steinbeck looks kind of like a stodgy old GK Chesterton sort of guy:

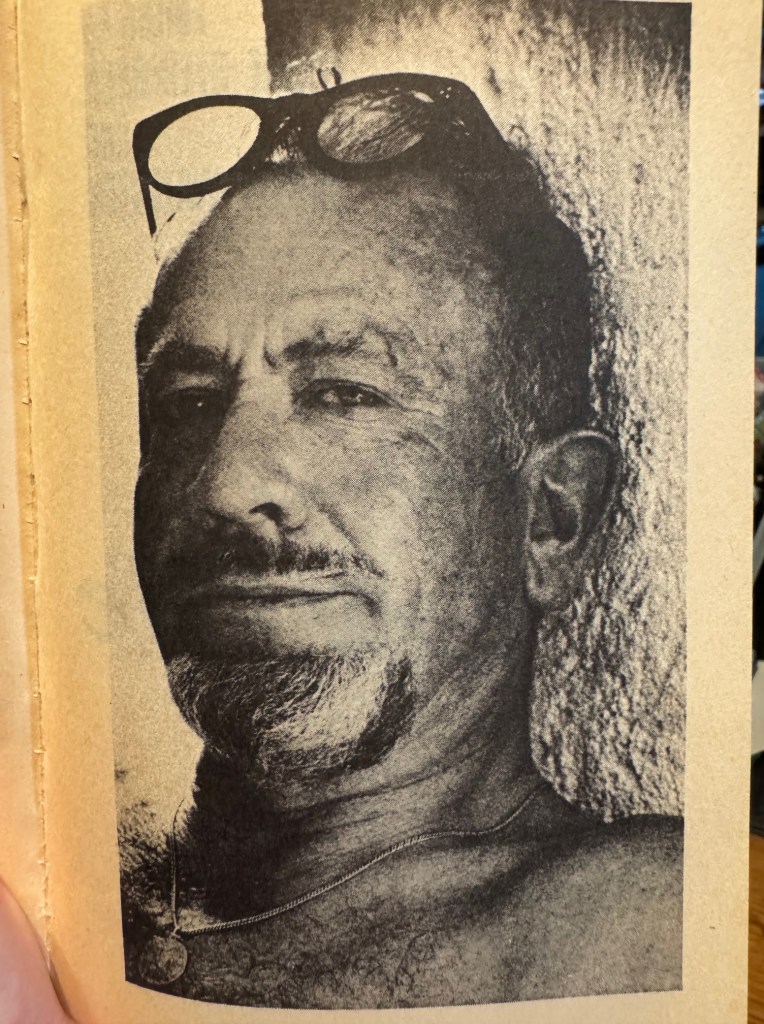

but inside there’s a photo of him where he looks more like the louche California artist:

He looks kind of like the late Brian Reich. Those two poles of Steinbeck are there in the book.

Here’s a bit more of that quoted letter:

New York

[November 5] 1959

Guy Fawkes Day

Dear Adlai:

Back from Camelot, [I think Steinbeck is referring to literal Camelot here, like King Arthur country in the UK, Steinbeck was obsessed with King Arthur and he’d just gone there to research] and, reading the papers not at all sure it was wise. Two first impressions. First a creeping, all-per-vading, nerve-gas of immorality which starts in the nursery and does not stop before it reaches the highest offices, both corporate and governmental. Two, a nervous restlessness, a hunger, a thirst, a yearning for something unknown-per-haps morality. Then there’s the violence, cruelty and hypocrisy symptomatic of a people which has too much, and last the surly, ill-temper which only shows up in humans when they are frightened.

Adlai, do you remember two kinds of Christmases? There is one kind in a house where there is little and a present represents not only love but sacrifice. The one single package is opened with a kind of slow wonder, almost reverence.

Once I gave my youngest boy, who loves all living things, a dwarf, peach-faced parrot for Christmas. He removed the paper and then retreated a little shyly and looked at the little bird for a long time. And finally he said in a whisper, “Now who would have ever thought that I would have a peach-faced parrot?”

Then there is the other kind of Christmas with presents piled high, the gifts of guilty parents as bribes because they have nothing else to give. The wrappings are ripped off and the presents thrown down and at the end the child says-“Is that all?”

Well, it seems to me that America now is like that second kind of Christmas. Having too many THINGS they spend their hours and money on the couch searching for a soul. A strange species we are. We can stand anything God and Nature can throw at us save only plenty. If I wanted to destroy a nation, I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy and sick. And then I think of our “Daily” in Somerset, who served your lunch. She made a teddy bear with her own hands for our grandchild. Made it out of an old bath towel dyed brown and it is beautiful. She said, “Sometimes when I have a bit of rabbit fur, they come out lovelier.” Now there is a present. And that obviously male Teddy Bear is going to be called for all time MIZ Hicks.

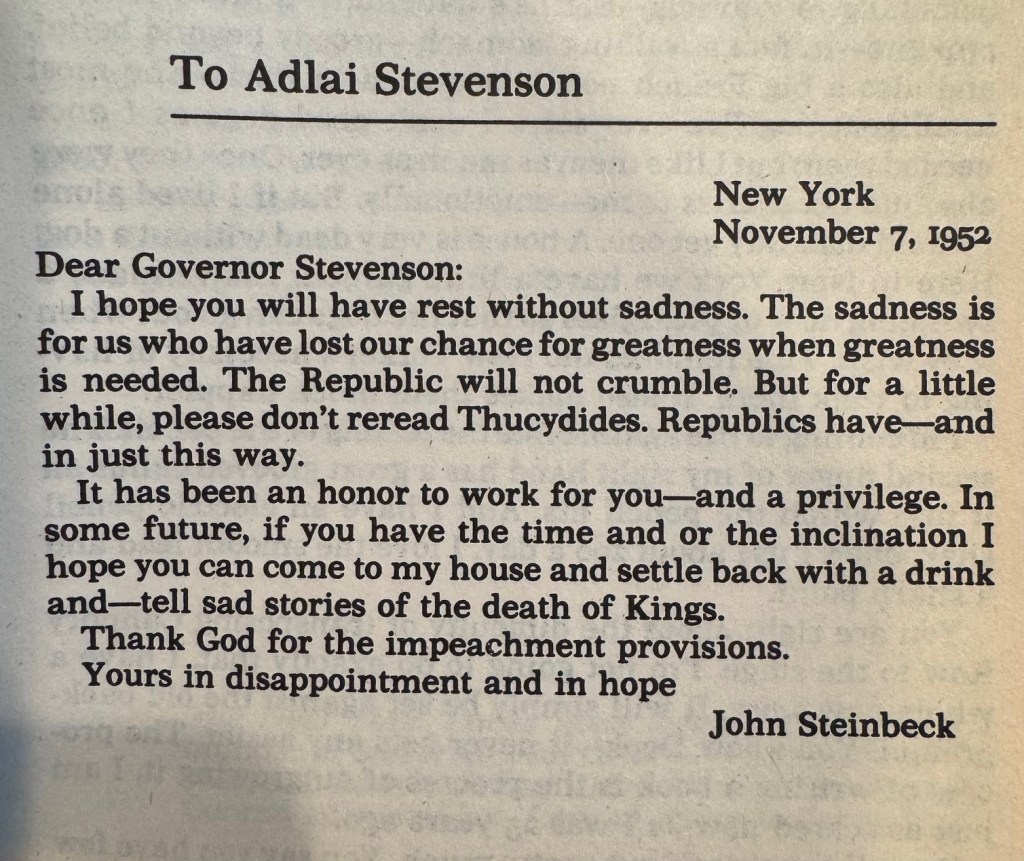

Kind of a conservative idea in a way. Yet Steinbeck is writing to Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic candidate for president. Steinbeck did some speechwriting for Adlai. When Adlai lost to Eisenhower in 1952, Steinbeck wrote him this one:

It seems a bit drastic in retrospect, Eisenhower is mostly regarded as a pretty good president, certainly by comparison, although he did overthrow a few foreign governments (see discussion of Guatemala in Hely’s The Wonder Trail.) But I guess they really felt this at the time.

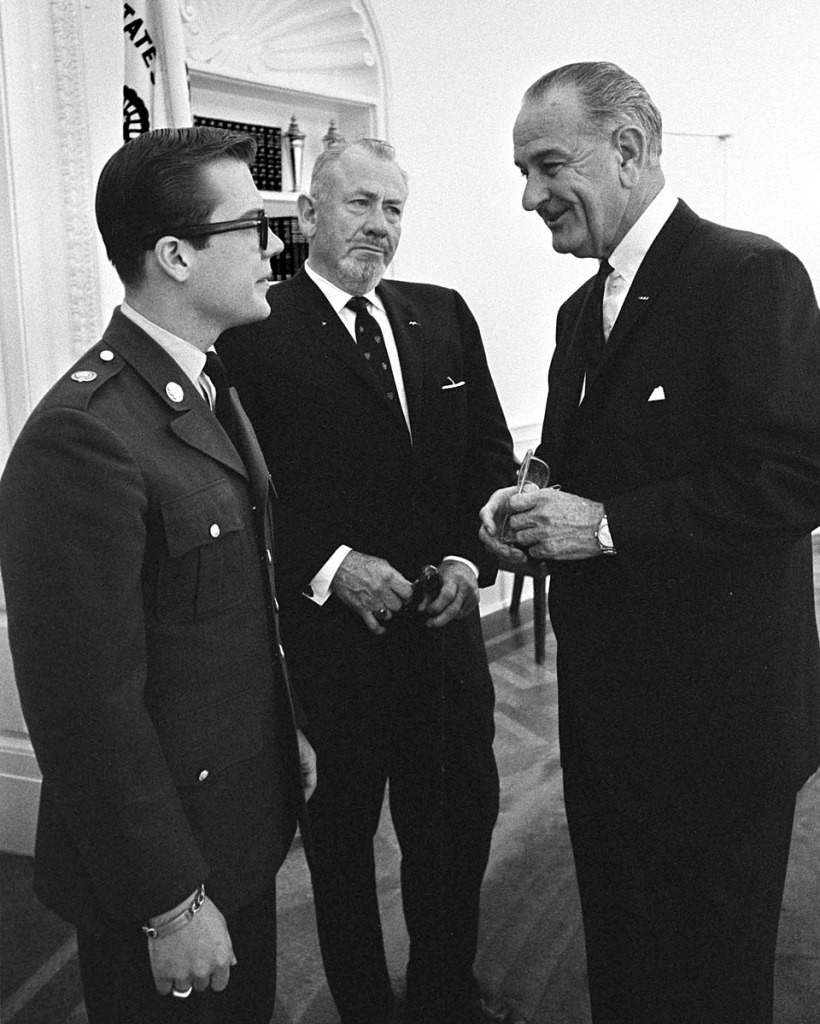

Yet, only a few hundred pages later in the book, in 1966, Steinbeck is writing to LBJ telling him not to get discouraged by anti-Vietnam War protestors:

I know that you must be disturbed by the demonstrations against policy in Vietnam. But please remember that there have always been people who insisted on their right to choose the war in which they would fight to defend their country. There were many who would have no part of Mr.

Adams’ and George Washington’s war. We call them Tories.

There were many also who called General Jackson a butcher. Some of these showed their disapproval by selling beef to the British. Then there were the very many who de nounced and even impeded Mr. Lincoln’s war. We call them Copperheads. I remind you of these things, Mr. President, because sometimes, the shrill squeaking of people who simply do not wish to be disturbed must be saddening to you. I assure you that only mediocrity escapes criticism.

The context there was that Steinbeck’s son was headed to Vietnam.

After his service John IV apparently became an anti-war advocate and Buddhist practioner:

He wrote about his experiences with the Vietnamese and GIs. Steinbeck took the vows of a Buddhist monk while living on Phoenix Island in the Mekong Delta, under the tutelage of the Coconut Monk, a silent tree-dwelling mystic yogi who adopted Steinbeck as a spiritual son. Amid the raging war, Steinbeck stayed in the monk’s “peace zone”, where the 400 monks who lived on the island hammered howitzer shell casings into bells.

Steinbeck’s politics are a whole academic mini-field: type “Steinbeck’s politics” into Jstor and 1,339 results come up.

The shifting meanings of conservative and liberal and associated ideas are interesting. If Hemingway and Fitzgerald had lived long enough, I’m sure their political transitions would’ve been quite interesting as well. I’m interested in the idea of America as a spoiled child on Christmas morning.

From an interview with William Souder, author of Mad At The World: A Life of John Steinbeck:

Library of America: Let’s start with your very evocative title. What was Steinbeck so mad about?

William Souder: It’s tempting to say “everything,” and let it go at that. Steinbeck was, in so many ways, America’s most pissed-off writer. In grade school, he befriended a classmate who was shy and got picked on. When he was asked why he wasted time with a boy nobody else liked, Steinbeck answered simply, “Because somebody has to take care of him.” Steinbeck could never abide a bully. Later, as a writer, Steinbeck filled his stories with people who were marginalized in a world he perceived in stark black-and-white.

Steinbeck believed in good and evil, and he was convinced that morality was inversely proportional to your lot in life. Being good too often meant having little to show for it, he thought. This was especially true during the Great Depression, when millions of honest, hard-working citizens were dispossessed and displaced—many of them Dust Bowl refugees who ended up toiling for appallingly low wages in California’s farm fields. Steinbeck investigated the plight of the “Okies” and saw firsthand their squalid roadside camps, haunted by disease and starvation. The migrants were brutalized by the landowners who needed them and also despised them.

In 1938, Steinbeck, who thought the confrontations between the migrants and the landowners’ squads of vigilante enforcers could escalate into civil war, began work on a novel about the situation, focusing it on the oppressive tactics of the big farm interests. After a few months he tore up the manuscript and started over, telling the story this time from the point of view of the oppressed—a family named Joad from Oklahoma. Steinbeck, seething and telling himself again and again to work slowly and carefully, wrote The Grapes of Wrath, long since acclaimed as one of the greatest books in the American canon, in a rage and in a rush. He didn’t have to push himself. He was fueled by anger.

Elmore Leonard on what Steinbeck taught him.

Our previous coverage of John Steinbeck.