A Farewell To Arms (1929)

Posted: August 30, 2024 Filed under: Hemingway, Switzerland Leave a comment

serves as an artifact of a bygone craft

says a quote (NY Times) on the cover of my Hemingway Library copy. I believe that’s referring to this specific edition which includes a lot of Hemingway’s revisions and alternate drafts, but can we escape the idea that maybe the novel itself is a bygone craft?

I saw that the novel, which at my maturity was the strongest and supplest medium for conveying thought and emotion from one human being to another, was becoming subordinated to a mechanical and communal art that, whether in the hands of Hollywood merchants or Russian idealists, was capable of reflecting only the tritest thought, the most obvious emotion. It was an art in which words were subordinate to images, where personality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration. As long past as 1930, I had a hunch that the talkies would make even the best selling novelist as archaic as silent pictures.

so said Fitzgerald, Hemingway frenemy and penis-measuring subject in The Crack-Up.

A Farewell To Arms was made into two different movies. I haven’t seen either of them but I’ve watched the trailers on YouTube and they both appear kinda lame, missing the essence, which comes from the point of view and the style.

This might be the most famous passage from AFTA:

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain. We had heard them, sometimes standing in the rain almost out of earshot, so that only the shouted words came through, and had read them, on proclamations that were slapped up by billposters over other proclamations, now for a long time, and I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it. There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

Concrete names are a big feature of the book: Udine, Campoformio, Tagliamento, Cividale, Caporetto. I read the book with a map of Italy at hand but doesn’t it work without it? Near the climax when Frederick Henry must row with Catherine to Switzerland to escape the war he’s given this instruction:

Past Luino, Cannero, Cannobio, Tranzano. You aren’t in Switzerland until you come to Brissago. You have to pass Monte Tamara.

More:

“If you row all the time you ought to be there by seven o’clock in the morning.”

“Is it that far?”

“It’s thirty-five kilometres.”

“How should we go? In this rain we need a compass.”

“No. Row to Isola Bella. Then on the other side of Isola Madre with the wind. The wind will take you to Pallanza. You will see the lights. Then go up the shore.’

“Maybe the wind will change.”

“No,” he said. “This wind will blow like this for three days. It comes straight down from the Mattarone. There is a can to bail with.”

“Let me pay you something for the boat now.”

“No, I’d rather take a chance. If you get through you pay me all you can.”

“All right.”

“I don’t think you’ll get drowned.”

“That’s good.”

“Go with the wind up the lake.”

“All right.” I stepped in the boat.

“Did you leave the money for the hotel?”

“Yes. In an envelope in the room.”

“All right. Good luck, Tenente.”

“Good luck. We thank you many times.”

“You won’t thank me if you get drowned.”

On this read I considered the advice Hemingway gave to Maestro:

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise.

Plug that into the scene where Henry gets wounded:

“This isn’t a deep dugout,” Passini said.

“That was a big trench mortar.”

“Yes, sir.”

I ate the end of my piece of cheese and took a swallow of wine.

Through the other noise I heard a cough, then came the chuh-chuhchuh-chuh-then there was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red and on and on in a rushing wind. I tried to breathe but my breath would not come and I felt myself rush bodily out of myself and out and out and out and all the time bodily in the wind. I went out swiftly, all of myself, and I knew I was dead and that it had all been a mistake to think you just died. Then I floated, and instead of going on I felt myself slide back. I breathed and I was back. The ground was torn and in front of my head there was a splintered beam of wood.

In the jolt of my head I heard somebody crying. I thought somebody was screaming. I tried to move but I could not move. I heard the machine-guns and rifles firing across the river and all along the river. There was a great splashing and I saw the star-shells go up and burst and float whitely and rockets going up and heard the bombs, all this in a moment, and then I heard close to me some one saying “Mama Mia! Oh, mama Mia!” I pulled and twisted and got my legs loose finally and turned around and touched him. It was Passini and when I touched him he screamed.

Much of the book mirrors Hemingway’s own experience, but in kind of a juiced up way. Hemingway was wounded in the war, but he was an ambulance driver with the Red Cross. Henry is a lieutenant in the Italian army. (Why? “I was in Italy.”) Hemingway has promoted himself. Hemingway in real life had an affair with a nurse, who then broke things off while Hemingway was back in Chicago. (An apparently close to biographical facts version of this story is told by Hemingway in “A Very Short Story.”) In the AFTA version, the nurse falls in love with Henry, escapes with him, is going to have his baby.

The most vivid part of the book is the retreat from Caporetto. Hemingway wasn’t at the retreat from Caporetto, but he’d heard about it.

In Italy when I was at the war there, for one thing that I had seen or that had happened to me, I knew many hundreds of things that had happened to other people who had been in the war in all of its phases. My own small experiences gave me a touchstone by which I could tell whether stories were true or false and being wounded was a password.

I’m reminded of Mike White telling Marc Maron that he tried to make a version of himself that exaggerated his flaws, leaning into his awkward, uncomfortable self, to make Chuck & Buck. Then he saw Good Will Hunting and saw that Matt Damon and Ben Affleck had made versions of themselves that were cooler, better, good with kids, getting in fights, exaggeratedly great.

There’s a part of A Farewell to Arms where Tenente Henry rates his own courage:

“They won’t get us,” I said. “Because you’re too brave. Nothing ever happens to the brave.”

“They die of course.”

“But only once.”

“I don’t know. Who said that?”

“The coward dies a thousand deaths, the brave but one?”

“He was probably a coward,” she said. “He knew a great deal of them perhaps.”

“I don’t know. It’s hard to see inside the head of the brave”

“Yes. That’s how they keep that way.”

“You’re an authority.”

“You’re right, darling. That was deserved.”

“You’re brave.

“No,” she said. “But I would like to be.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I know where I stand. I’ve been out long enough to know. I’m like a ball-player that bats two hundred and thirty and knows he’s no better.”

“What is a ball-player that bats two hundred and thirty? It’s awfully impressive.”

“It’s not. It means a mediocre hitter in baseball.”

“But still a hitter,” she prodded me.

“I guess we’re both conceited,” I said. “But you are brave.”

“No. But I hope to be.”

“We’re both brave,” I said. “And I’m very brave when I’ve had a drink.”

A funny part is how many liquor bottles Miss Van Campen finds in Henry’s hospital room:

“Miss Gage looked. They had me look in a glass. The whites of the eyes were yellow and it was the jaundice. I was sick for two weeks with it. For that reason we did not spend a convalescent leave together. We had planned to go to Pallanza on Lago Maggiore. It is nice there in the fall when the leaves turn. There are walks you can take and you can troll for trout in the lake. It would have been better than Stresa because there are fewer people at Pallanza. Stresa is so easy to get to from Milan that there are always people you know. There is a nice village at Pallanza and you can row out to the islands where the fishermen live and there is a restaurant on the biggest island. But we did not go.

One day while I was in bed with jaundice Miss Van Campen came in the room, opened the door into the armoire and saw the empty bottles there. I had sent a load of them down by the porter and I believe she must have seen them going out and come up to find some more. They were mostly vermouth bottles, marsala bottles, capri bottles, empty chianti flasks and a few cognac bottles.

The porter had carried out the large bottles, those that had held vermouth, and the straw-covered chianti flasks, and left the brandy bottles for the last. It was the brandy bottles and a bottle shaped like a bear, which had held kümmel, that Miss Van Campen found.

The bear-shaped bottle enraged her particularly. She held it up, bear was sitting up on his haunches with his paws up, there was a cork in his glass head and a few sticky crystals at the bottom. I laughed.

“It is kümmel,” I said. “The best kümmel comes in those bearshaped bottles. It comes from Russia.”

“Those are all brandy bottles, aren’t they?” Miss Van Campen asked.

“I can’t see them all,” I said. “But they probably are.”

“How long has this been going on?”

“I bought them and brought them in myself,” I said. “I have had Italian officers visit me frequently and I have kept brandy to offer them.’

“You haven’t been drinking it yourself?” she said.

“I have also drunk it myself.”

“Brandy,” she said. “Eleven empty bottles of brandy and that bear liquid.”

“Kümmel.”

“I will send for some one to take them away. Those are all the have?”

“For the moment.”

“And I was pitying you having jaundice. Pity is something that is wasted on you.”

“Thank you.”

(On this reading of the book it was clear that part of why Miss Van Campen is such a priss is she was horny for Henry and upset that he already had a girlfriend.)

Good times in Milan:

Afterward when I could get around on crutches we went to dinner at Biffi’s or the Gran Italia and sat at the tables outside on the floor of the galleria. The waiters came in and out and there were people going by and candles with shades on the tablecloths and after we decided that we liked the Gran Italia best, George, the head-waiter, saved us a table. He was a fine waiter and we let him order the meal while we looked at the people, and the great galleria in the dusk, and each other. We drank dry white capri iced in a bucket; although we tried many of the other wines, fresa, barbera and the sweet white wines. They had no wine waiter because of the war and George would smile ashamedly when I asked about wines like fresa.

“If you imagine a country that makes a wine because it tastes like strawberries,” he said.

“Why shouldn’t it?” Catherine asked. “It sounds splendid.”

“You try it, lady,” said George, “if you want to. But let me bring a little bottle of margaux for the Tenente.”

Biffi’s is still there, it’s not highly rated.

Abruzzo mentioned:

It was dark in the room and the orderly, who had sat by the foot of the bed, got up and went out with him. I liked him very much and I hoped he would get back to the Abruzzi some time. He had a rotten life in the mess and he was fine about it but I thought how he would be in his own country. At Capracotta, he had told me, there were trout in the stream below the town. It was forbidden to play the flute at night. When the young men serenaded only the flute was forbidden. Why, I had asked. Because it was bad for the girls to hear the flute at night. The peasants all called you “Don” and when you met them they took off their hats. His father hunted every day and stopped to eat at the houses of peasants. They were always honored. For a foreigner to hunt he must present a certificate that he had never been arrested. There were bears on the Gran Sasso D’Italia but it was a long way. Aquila was a fine town. It was cool in the summer at night and the spring in Abruzzi was the most beautiful in Italy. But what was lovely was the fall to go hunting through the chestnut woods. The birds were all good because they fed on grapes and you never took a lunch because the peasants were always honored if you would eat with them at their houses.”

At one point in the book the narrator is literally side-tracked: his train is diverted to a side track and stopped. The term “sidetracked” I have often heard in writers’ rooms to mean “going off in a side direction,” negative connotation. In the original usage it seems to have meant going nowhere, stopped.

The reason why I reread this book, which I hadn’t looked at since high school: towards the end Henry and Catherine take refuge in Montreux, Switzerland. We were going to Montreux and I wanted to hear what Hemingway had to say about it:

Sometimes we walked down the mountain into Montreux.

There was a path went down the mountain but it was steep and so usually we took the road and walked down on the wide hard road between fields and then below between the stone walls of the vineyards and on down between the houses of the villages along the There were three villages; Chernex, Fontanivent, and the other I forget. Then along the road we passed an old square-built stone château on a ledge on the side of the mountain-side with the terraced fields of vines, each vine tied to a stick to hold it up, the vines dry and brown and the earth ready for the snow and the lake down below flat and gray as steel. The road went down a long grade below the château and then turned to the right and went down very steeply and paved with cobbles, into Montreux.

We did not know any one in Montreux. We walked along beside the lake and saw the swans and the many gulls and terns that flew you came close and screamed while they looked down at when the water. Out on the lake there were flocks of grebes, small and dark, and leaving trails in the water when they swam.

In the town we walked along the main street and looked in the windows of the shops. There were many big hotels that were closed but most of the shops were open and the people were very glad to see us. There was a fine coiffeur’s place where Catherine went to have her hair done. The woman who ran it was very cheerful and the only person we knew in Montreux. While Catherine was there I went up to a beer place and drank dark Munich beer and read the papers. I read the Corriere della Sera and the English and American papers from Paris. All the advertisements were blacked out, supposedly to prevent communication in that way with the enemy. The papers were bad reading. Everything was going very badly everywhere.

How much would Hemingway recognize today’s Montreux, the jazz festival Montreux, Deep Purple/Freddie Mercury/Russian emigre Montreux?

Maybe parts of the old town:

Here is a discussion question (contains a spoiler):

The end of the book is often presented as tragic. Catherine has died giving childbirth. Henry walks alone into the rain. But, is there a very cynical reading that this is actually a relief for Henry? From when he first met Catherine he suspected she might be “crazy.” Now the encumbrance of this woman and a baby he didn’t really want is lifted. Not only that he’s granted a pleasing tragedy to be sentimental about. Is this a male fantasy ending? All the credit, none of the work?

Recall the title of James Mellow’s biography of Hemingway: “A Life Without Consequences.” Is that the fantasy here? The only consequence is valuable experience, worldliness.

As usual with Hemingway the line between sentimental, romantic, and hardboiled, cynical is quite thin.

Everyday life in the Holy Roman Empire

Posted: July 27, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland Leave a comment

Ever since I saw this map while working through the history of Switzerland and the Savoy I’ve been wondering what the deal was with the Holy Roman Empire. Peter Wilson’s book, The Holy Roman Empire, is a fantastic introduction and I hope to write up something about it once I finish its many hundreds of surprisingly compelling pages.

Wilson adds to Voltaire’s quip that it was neither holy, Roman, nor an empire by pointing out that it didn’t even call itself the Holy Roman Empire. What happened was: the vacuum left after the Roman empire bothered everybody, especially because there should be a guy who was in charge of like Christendom. In the year 800, Pope Leo II declared that Charlemagne was like the new Roman emperor. For the next few hundred years, there was a delicate game between the Pope and whoever could gather the right combo of force and legitimacy and political support to get himself named the Emperor. The Emperor would travel around – a stop at Charlemagne’s spot in Aachen was mandatory. The Empire itself was quite fractured but seems to have held together pretty well.

I put my search for a good Holy Roman Empire book to Twitter and user Max S. recommended this one:

It’s a dense one, and I haven’t consumed all of it, but there are some vivid snapshots of life in this era. The world post the calamitous 14th century:

The career of Tommy Platter:

And a different path:

a smart roundup on witch trials, which we’ve considered before:

Agree that witch trials will never yield their secrets to the historian’s tools. Anyway: pleasing way to pass some time in a lethargic summer in Hollywood.

Geneva Conventions (Swiss History Part Seven)

Posted: June 9, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland 1 CommentI believe this will conclude our unit on the history of Switzerland. Here you can find Part One about pre-Switzerland to the Dark Ages, Part Two about the Bernese chronicles, Part Three about founding myths like William Tell and the Rütli oath, Part Four about the various leagues up to the Congress of Vienna, Part Five about Steinberg’s Why Switzerland, and Part Six about Calvin/Cauvin’s Geneva.

Henry Dunant was a thirty one year old Swiss businessman who was trying to arrange some deals in French-held Algeria. He was running into problems, the land and water rights were all a jumble. So he came up with a plan:

Dunant wrote a flattering book full of praise for Napoleon III with the intention to present it to the emperor, and then traveled to Solferino to meet with him personally.

Napoleon III, Emperor of France, was in a war with Austria at the time. Dunant arrived on the evening after a massive battle. There were something like 40,000 dead and wounded people around.

No one was helping them.

Shocked, Dunant himself took the initiative to organize the civilian population, especially the women and girls, to provide assistance to the injured and sick soldiers. They lacked sufficient materials and supplies, and Dunant himself organized the purchase of needed materials and helped erect makeshift hospitals. He convinced the population to service the wounded without regard to their side in the conflict as per the slogan “Tutti fratelli” (All are brothers) coined by the women of nearby city Castiglione delle Stiviere. He also succeeded in gaining the release of Austrian doctors captured by the French and British.

When he got home, he wrote up a book called A Memory of Soferino, in which he described what he saw and set forth the idea that a neutral organization that could help the wounded in war would be valuable.

On February 7, 1863, the Société genevoise d’utilité publique [Geneva Society for Public Welfare] appointed a committee of five, including Dunant, to examine the possibility of putting this plan into action. With its call for an international conference, this committee, in effect, founded the Red Cross.

That’s from the Nobel Prize website; Dunant won the first ever Nobel Peace Prize.

A year after the founding of the Red Cross, the government of Switzerland invited all European countries as well as the US, Mexico and Brazil to a conference where they agreed on the first Geneva Convention “for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field”. They met in the Alabama room of Geneva’s city hall. Now, why was it called the Alabama room? Because that’s where an international tribunal met to work out the Alabama Claims, an international dispute between the US and the UK regarding grievances over Confederate raiders, including the Alabama, which were built in the UK and used against the US.

The Alabama.

So, Geneva already had a rep as a place for international meetings.

As for Dunant, he went bust. Says Nobel Prize.org:

After the disaster, which involved many of his Geneva friends, Dunant was no longer welcome in Genevan society. Within a few years he was literally living at the level of the beggar. There were times, he says, when he dined on a crust of bread, blackened his coat with ink, whitened his collar with chalk, slept out of doors.

For the next twenty years, from 1875 to 1895, Dunant disappeared into solitude. After brief stays in various places, he settled down in Heiden, a small Swiss village. Here a village teacher named Wilhelm Sonderegger found him in 1890 and informed the world that Dunant was alive, but the world took little note. Because he was ill, Dunant was moved in 1892 to the hospice at Heiden. And here, in Room 12, he spent the remaining eighteen years of his life. Not, however, as an unknown. After 1895 when he was once more rediscovered, the world heaped prizes and awards upon him.

Despite the prizes and the honors, Dunant did not move from Room 12. Upon his death, there was no funeral ceremony, no mourners, no cortege. In accordance with his wishes he was carried to his grave «like a dog»3.

The Red Cross calls me just about every day about giving blood. I’ve got to do that again.

Calvin’s Geneva (Swiss History Part Five or Six)

Posted: June 7, 2024 Filed under: religion, Switzerland Leave a commentPrevious posts on Swiss history.

Jean Cauvin was a twenty-four year old lawyer and scholar when his friend/ally gave a speech at the University of Paris that was so scandalous the guy had to leave town and move to Basel. The topic of the speech? Reforming the Catholic Church.

Shortly after events got so heated (y’all remember The Affair of the Placards) that Calvin had to leave town too. The Universal History of the World picks up:

The Universal History of the World, which I bought volume by volume for 50 cents each at the Needham Public Library, really fired up my youthful imagination. The book has a slight Protestant slant.

Wikipedia gives us Voltaire’s take on the reign of Calvin:

Voltaire wrote about Calvin, Luther and Zwingli, “If they condemned celibacy in the priests, and opened the gates of the convents, it was only to turn all society into a convent. Shows and entertainments were expressly forbidden by their religion; and for more than two hundred years there was not a single musical instrument allowed in the city of Geneva. They condemned auricular confession, but they enjoined a public one; and in Switzerland, Scotland, and Geneva it was performed the same as penance.”

Marilynne Robinson, in her Death of Adam, has a long essay sticking up for Calvin (she uses the spelling Cauvin):

Still, I would like to consider a little longer the strange figure of Jean Cauvin himself, because he is a true historical singularity. The theologian Karl Barth called him “a cataract, a primeval forest, something demonic, directly descending from the Himalayas, absolutely Chinese, marvelous, mythological.”

…

His commentaries on the Psalms and on Jeremiah are each about twenty-five hundred pages long in English translation, and he wrote commentary on almost the whole Bible, besides personal, pastoral, polemical, and diplomatic letters, treatises on points of doctrine, a catechism, and continuous revisions of his Institutes of the Christian Religion, the first, greatest, and most influential work of systematic theology the Reformation produced.

Robinson points out that by way of Geneva, many Protestant exiles who ended up in the future USA had an example of a republican type of government:

There are things for which we in this culture clearly are indebted to him, including relatively popular government, the relatively high status of women, the separation of church and state, what remains of universal schooling, and, while it lasted, liberal higher education, education in “the humanities.” All this, for our purposes, emanated from Geneva—in imperfect form, of course, but tending then toward improvement as it is now tending toward decline.

and:

In 1528 Geneva became an autonomous city governed by elected councils as the result of an insurrection against the ruling house of Savoy. Though the causes of the rebellion seem to have had little to do with the religious controversies of the period, in the course of it two preachers, Guillaume Farel and Pierre Viret, persuaded the city to align itself with the Reformation, then recruited Cauvin to guide the experiment of establishing a new religious culture in the newly emancipated city. That is to say, Calvinism developed with and within a civil regime of elections and town meetings…

Again, the republican institutions of Geneva were in place before Calvin set foot in that city; the Northern Netherlands freed itself and governed itself under Calvinist influence, which was strong but never exclusive; the New Englanders embraced a revolutionary order whose greatest exponents were Southerners.

She suggests we ease up on Calvin, after all he only executed the one heretic:

Bear in mind that Calvin approved the execution of only one man for heresy, the Spanish physician known as Michael Servetus, who had written books in which, among other things, he attacked the doctrine of the Trinity. One man is one too many, of course, but by the standards of the time, and considering Calvin’s embattled situation, the fact that he has only Servetus to answer for is evidence of astonishing restraint.

But she notes some difficult aspects:

Cauvin has an unsettling habit of referring to himself or to any human being as a “worm.”

I hope to learn more about John Calvin/Cauvin in Geneva. I find myself more drawn to Servetus:

Servetus also contributed enormously to medicine with other published works specifically related to the field, such as his Complete Explanation of Syrups

When Calvin died, they were worried his resting place would become a place of veneration, as for a saint, which he wouldn’t approve of, so he was buried in an unmarked grave.

Why Switzerland? by Jonathan Steinberg

Posted: June 2, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland Leave a commentMuch to admire about this book.

About that civil war, 1847. A group of southern cantons decided they weren’t being treated well and wanted to separate. Here’s how it went down:

(Could our civil war have ended fast too, with a lighting strike at the heart of the Confederacy? Did we dither too much because the guy at the time was the obese Winfield Scott? It seems like Lincoln pushed for that, but the debacle at Bull Run ended the hope.)

On William Tell:

Religious segregation:

Huge distinction in Swiss political organization:

This strikes me as opposite the US. In the US the weight is at the top. Presidential elections are fanatical but local elections tend to be somewhat pathetic. The US President is a big deal. The Swiss president is elected for one year and has very few powers, they’re not even the head of state, they’re just sort of a tiebreaker if necessary. Right now it’s Viola Amherd:

There is an unwritten rule that the member of the Federal Council who has not been president the longest becomes president. Therefore, every Federal Council member gets a turn at least once every seven years. The only question in the elections that provides some tension is the question of how many votes the person who is to be elected president receives. This is seen as a popularity test.

The cover of the second edition is less spooky than the third:

Cheers to Steinberg for this valuable book full of insight.

The League of God’s House (Swiss History Part Four)

Posted: June 1, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland Leave a comment

The history of Switzerland is combinations of alliances. (Is that all history?) Places (cantons) form groups to fight invasions and encroachments. From the Habsburgs, from the Burgundians, from each other. If you watched a timelapse political map of Switzerland it grows… like a cancer? Like a growth. Cells combining. Watch the flags pass by as you scroll through this one.

One answer to Steinberg’s titular question, Why Switzerland? is The Congress of Vienna. French Revolutionary armies rolled all over Switzerland, Napoleon used it as he saw fit (he seemed to find it kind of amusing and sort of admirable, and thought a federation was the natural state for the Swiss). It was not peaceful during this time. There were 21,000 Russians at the battle of Gothard Pass.

After Waterloo, when the still standing powers sorted out the future of Europe, Swiss neutrality was guaranteed.

Staying neutral, that was the hard part. In the Concise History Church and Head mention that during WWI the average Swiss guy spent 605 days deployed patrolling the border, which was tough and boring. Active duty to keep Switzerland neutral. Active neutrality. That’s another answer to Steinberg’s question Why Switzerland?: the army/national service keeps the diverse cantons bonded together.

Contemplate the following alt outcome for Europe, past or future: instead of an EU, Switzerland expands, absorbing the states around it and then the whole continent into its federal system.

*Amarco90 took that photo of Chur.

Imperial immediacy

Posted: May 28, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland Leave a commentImperial immediacy (German: Reichsfreiheit or Reichsunmittelbarkeit) was a privileged constitutional and political status rooted in German feudal law under which the Imperial estates of the Holy Roman Empire such as Imperial cities, prince-bishoprics, and secular principalities, and such individuals as the Imperial knights, were declared free from the authority of any local lord, having no suzerain but the Holy Roman Emperor directly, without any intermediary authority: immediate = im- (negatory prefix) + mediate (in the sense of a third-party go-between, mediator); immediacy also applied to later institutions of the Empire such as the Diet (Reichstag), the Imperial Chamber of Justice and the Aulic Council.

Trying to work out what the deal was with the counts of Annecy, or counts of Geneva who had their seat at Annecy, and the House of Savoy.

Here’s some of what Wikipedia says under “Problems Understanding the Empire:”

The practical application of the rights of immediacy was complex; this makes the history of the Holy Roman Empire particularly difficult to understand, especially for modern historians. Even such contemporaries as Goethe and Fichte called the Empire a monstrosity. Voltaire wrote of the Empire as something neither Holy nor Roman, nor an Empire, and in comparison to the British Empire, saw its German counterpart as an abysmal failure that reached its pinnacle of success in the early Middle Ages and declined thereafter.[4] Prussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke described it in the 19th century as having become “a chaotic mess of rotted imperial forms and unfinished territories”. For nearly a century after the publication of James Bryce’s monumental work The Holy Roman Empire (1864), this view prevailed among most English-speaking historians of the Early Modern period, and contributed to the development of the Sonderweg theory of the German past.[5]

A revisionist view popular in Germany but increasingly adopted elsewhere[citation needed] argued that “though not powerful politically or militarily, [the Empire] was extraordinarily diverse and free by the standards of Europe at the time”. Pointing out that people like Goethe meant “monster” as a compliment (i.e. ‘an astonishing thing’), The Economist has called the Empire “a great place to live … a union with which its subjects identified, whose loss distressed them greatly” and praised its cultural and religious diversity, saying that it “allowed a degree of liberty and diversity that was unimaginable in the neighbouring kingdoms” and that “ordinary folk, including women, had far more rights to property than in France or Spain.

Perhaps a page from the Nuremberg Chronicle will help us understand how all this worked:

Nope!

Swiss History, Part Three

Posted: May 25, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland Leave a commentWe jumped ahead a bit to cover the Bernese and Lucernese chronicles, from around 1500. Some real tough stuff in there, but also some fun:

When we last left what’s now Switzerland it was the Dark Ages. That term’s become unpopular but we just don’t know that much about what was up. There seems to be enough record and lineage to know there were some saints: Saint Bernard of Menthon, for example, he of the dogs with the barrels.

Where are our firsthand sources on Saint Bernard? What lingers seems to be mostly unsourced legend and possible propaganda? We have some 9th century stories about Saint Gall:

but we’re getting into lore here:

Images of Saint Gall typically represent him standing with a bear

who knows?

The saints, it is arguable, were trying to live outside of History, at least political history, which was possibly the smart move in the year 900. Perhaps always. Or maybe that’s the wrong way to see them, maybe they were political actors just like the counts of Annecy and the kings of Burgundy but with a holy varnish.

Between the Romans and what came next, the saints seem to have had the most lasting legacy: structures that still stand and names that are known.

The Rütli

In 1291, when the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf of Habsburg, died, the Helvetians decided their moment had come. On August 1, before a new emperor could be elected by a council of German princes, the elders of the three small states met on a tiny heath known as the Rütli on the shores of the Lake of Lucerne and negotiated an “eternal pact.” They declared their right to local self-government, promised one another assistance against any encroachment upon these rights and committed future generations to an alliance that was to “endure forever.” The pact was the beginning of the Everlasting League and the foundation of the Swiss Confederation. The forest meadow, the Rütli, accessible only by boat or by foot down a steep trail, is Switzerland’s most venerated patriotic shrine. Every school child is required to make at least one pilgrimage to it.

So says Herbert Kubly in the Time Life Switzerland. You’d think he’d include a picture of the Rutli, but he doesn’t. Maybe not his decision. That must’ve been frustrating in the days before you could find thousands of images of anything in one second.

A key word you come across in Swiss history is Eidgenossenschaft. Says Wiki:

Eidgenossenschaft is a German word specific to the political history of Switzerland. It means “oath commonwealth” or “oath alliance” in reference to the “eternal pacts” formed between the Eight Cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy of the late medieval period, most notably in Swiss historiography being the Rütlischwur between the three founding cantons Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden, traditionally dated to 1307. In modern usage, it is the German term used as equivalent with “Confederation” in the official name of Switzerland.

But how could a town/canton make a pledge? A person can make an oath, but can a canton? Clive H. Church and Randolph C. Head, in their Concise History of Switzerland, say:

Urban autonomy was common across medieval Europe, and many rural communities adopted corporate forms of organization in the High Middle Ages, but rural communities with imperial liberty emerged in only a few areas, notably in the central Alps. Valley communities in the mountains from the Valais to the Grisons organized as political corporations bearing seals and administering justice, and once they had gained sufficient legal privileges and autonomy, joined as equal members the networks of alliances among communes that characterized the entire region. Several factors enabled this development: location on the passes critical to imperial policy in Italy, the relative weakness of the major feudal dynasties and the high degree of cooperation demanded by pastoralism in the Alps, which encouraged strong collective institutions. Living in a diverse landscape of nobles, towns and cities also provided models and sometimes the impetus to organize on corporate lines. Historians have pointed to the emergence of alliances that included both urban and rural communes as a distinctive feature that enabled the Swiss leagues to thrive and survive after 1500, even as primarily urban alliances elsewhere foundered.

Here is Schwyz, from which Switzerland gets her name:

(Markus Bernet took that one.)

The truth or details about all this is still somewhat disputed, but a pact among the cantons is the key to Swiss history.

Together they fought off the Hapsburgs:

This was an intense time:

Source is this great site, Swiss History: Fact of Fake News, which goes into much detail about how much to trust our historians.

William Tell

You can’t talk about Swiss history without addressing William Tell, supposedly made to shoot an apple off his son’s head by a tyrannical Habsburg reeve (or vogt)? The earliest reference to him comes in The White Book of Sarnen, put together in 1474 by a country scribe named, conveniently, Schriber. (I learn all that here).

Both Church and Head in their Concise History of Switzerland and Steinberg in Why Switzerland? (great title) delicately broach the idea that William Tell very likely never existed, but he was so important as an idea to the Swiss that he’s significant. You can go as deep as you want on the historicity of Bill Tell. I found this interesting:

Rochholz (1877) connects the similarity of the Tell legend to the stories of Egil and Palnatoki with the legends of a migration from Sweden to Switzerland during the Middle Ages.

That’s Tell by Ferdinand Hodler:

Hodler’s life gives us a snapshot of everday Swiss history as it existed in the 19th century:

Hodler was born in Bern, the eldest of six children. His father, Jean Hodler, made a meager living as a carpenter; his mother, Marguerite (née Neukomm), was from a peasant family. By the time Hodler was eight years old, he had lost his father and two younger brothers to tuberculosis. His mother remarried, to a decorative painter named Gottlieb Schüpach who had five children from a previous marriage. The birth of additional children brought the size of Hodler’s family to thirteen.

The family’s finances were poor, and the nine-year-old Hodler was put to work assisting his stepfather in painting signs and other commercial projects. After the death of his mother from tuberculosis in 1867, Hodler was sent to Thun to apprentice with a local painter, Ferdinand Sommer. From Sommer, Hodler learned the craft of painting conventional Alpine landscapes, typically copied from prints, which he sold in shops and to tourists.

When we come back: Jean Cauvin and why there were no musical instruments in Geneva for two hundred years.

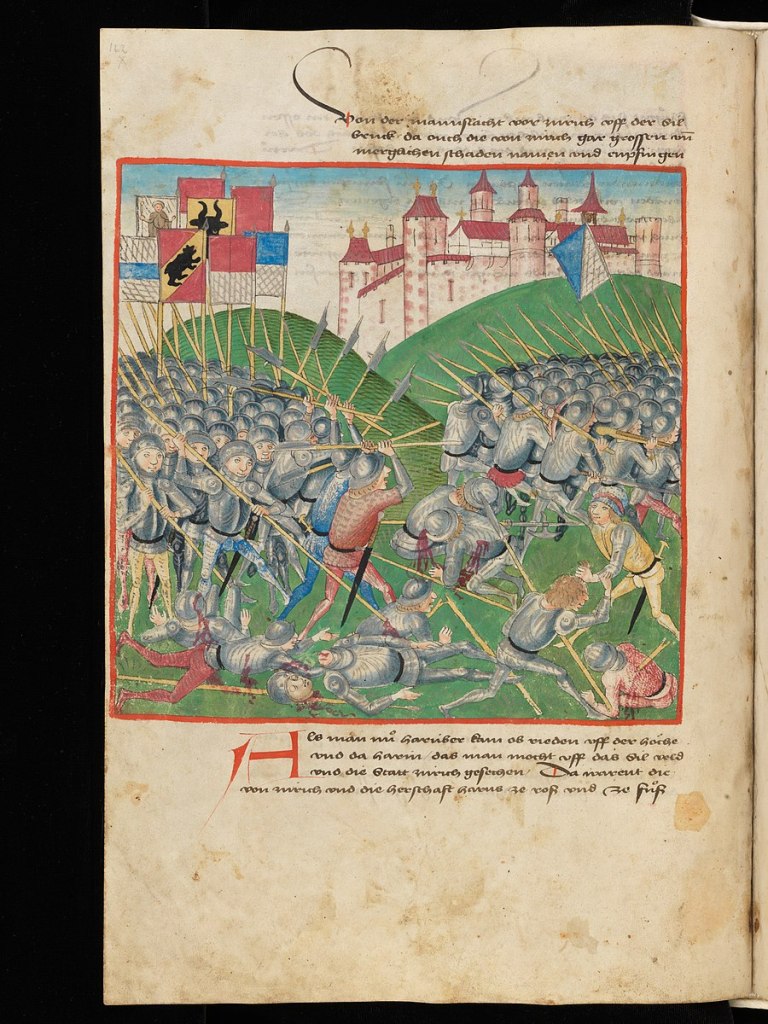

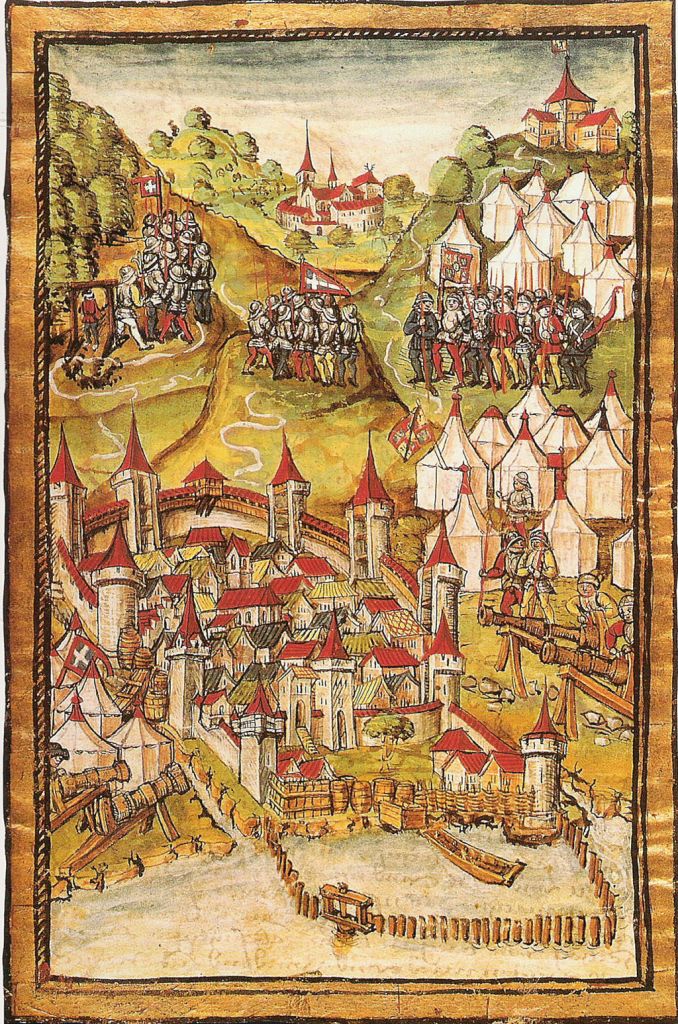

Bernese Chronicles (Swiss History Part Two)

Posted: May 19, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland 2 CommentsOur attempts to learn the history of Switzerland led us to a swirling eddy that is the chronicles of the city/canton of Bern. Illustrated books created to record notable events centered on the 1400s.

These depict in vivid detail the Swabian and Burgundian Wars.

Diebold Schilling the Elder was the uncle of Diebold Schilling the Younger.

Here is the work of the Younger, who created a similar chronicle for Lucerne:

Those are rampages through the Vaud.

The battle of Dorneck.

Entire chronicles can be found online, they’re shockingly long. Even a browse through them can be numbing. It’s like the work of Henry Darger or something, obsessive numbers of battle scenes and sieges and killings. Regrettably my German is insufficient for me to read them. I suspect I get the idea.

The events depicted kept the Burgundians and Habsburgs out of Switzerland and allowed the Old Swiss Confederacy to maintain its independence.

During this period the Swiss became so good at war that they became in demand mercenaries in Italy and elsewhere (the origin of the Vatican’s Swiss Guards?). Their super-weapon was the halberd, which was capable of killing a mounted knight. Defeating a guy on horseback who was armed with metal sword from your feet was a vexing fighting problem of the time. The Inca did not solve it in time.

Much praise to Ursula Kampmann for her article on Swiss historiography.

The death of the Burgundian Charles The Bold at the battle of Nancy ended the Burgundian hopes for swallowing pieces of the Swiss Confederacy:

The corpse of Charles the Bold remained concealed until three days after the battle, when it was found lying on the river, with half of his head frozen.[308] It took a group consisting of Charles’ Roman valet, his Portuguese personal physician, his chaplain, Olivier de la Marche, and two of his bastard brothers to identify the corpse through a missing tooth, ingrown toenail, and long fingernails

One cheek had been chewed away by wolves and the other embedded in frozen slime.

so said Wikipedia at one time (source for this claim?). It was a halberd that got him.

from a footnote on Charles’ Wiki page:

he word Eidgenossen is literary translated as ‘oath companion’, and was a synonym for Swiss, referring to the members of the Old Swiss Confederacy.[286] Until the Siege on Morat, most of the confederacy had not declared war on Burgundy, because Charles had yet to invade a territory officially part of one of its members. But during the siege, Charles attacked a bridge which was a part of Bernese territory, thus obligating the confederacy to join Bern in their campaign against Burgundy.

Charles’ death left Mary of Burgundy in charge. I’ve been meaning to put together something about all the depictions of her in art, but that’ll have to be another day.

And Switzerland stayed independent.

The Swiss are not in the EU. Switzerland itself is a kind of mini EU, a union of 26 cantons, mini nations, that speak French, Italian, German, Romansh. You can see how alliances of any kind would be a serious topic in Switzerland.

That’s enough for now.

I hope to visit Bern, it looks cool. Einstein lived there.

CucombreLibre from New York, NY, USA took that for Wikipedia.

How big is Switzerland compared to California?

Posted: May 13, 2024 Filed under: Switzerland Leave a comment

looking it up for my own purposes, but I’ll cop to making a cheap ploy for traffic, as various map comparisons are one of the biggest drivers of stray Google searches to this site.

And here’s Switzerland compared to Colorado:

Here by the way is Jim Simons musing on a possible future for the USA:

Zierler:

And Jim, on that point, thinking about where China is headed in the 21st century, where are the similarities to the Cold War? In other words, when we had Sputnik, it was almost like it was a zero-sum game. Russia’s advance was our loss. To what extent do you see that same dynamic at play now with China – where is there competition and where is there cooperation?

Simons:

You know, I don’t know enough about it to talk very intelligently. It’s clear that the Chinese are spending a lot on science and building it up. You know, I see the United States— Look, China is five times the size, four times the size of the United States. We have 300 million people, I think they have 1.2 billion or 1.3 billion. India has a lot of people. So relatively speaking, we’re not such a big country. But we do have some wonderful things. We have great universities in the United States, and so what I’m hoping, although like Switzerland, it’s a small country but it’s very prosperous country, because it’s focused on what it can do best. And done very well for years, Switzerland. So if you compare, sometimes, the United States could be a very big Switzerland, focusing on education, keeping our great public and private universities, that attracts people to come to the United States, and does a lot of research and so on. So in China with all its people, will, you know, be a very big force. There’s nothing we can do about it, but we can, you know, cooperate with them to some extent, so we don’t have to fight with them. But we want to stay ahead as long as we can.

I think we’re a bit too manic to settle into that, but it’s an intriguing thought.

The first woman to climb Mont Blanc

Posted: April 26, 2024 Filed under: mountains, Switzerland Leave a comment

from a March 06, 1965 New Yorker article about Swiss mountaineering by Jeremy Bernstein.