The Gentleman of Elvas

Posted: October 9, 2024 Filed under: Florida Leave a comment

“Hernando de Soto was the son of an esquire of Xeréz de Badajoz, and went to the Indias of the Ocean sea, belonging to Castile, at the time Pedrárias Dávila was the Governor. He had nothing more than blade and buckler: for his courage and good qualities Pedrárias appointed him to be captain of a troop of horse, and he went by his order with Hernando Pizarro to conquer Peru.” The words are those of a Portuguese knight known only as the Gentleman of Elvas, a witness to and survivor of the long and agonizing disaster that was de Soto’s Florida enterprise.

The Gentleman of Elvas is one of several members of that expedition whose accounts have come down to us, and his was the first to be published, in 1557.

An English translation by the geographer Richard Hakluyt appeared in 1609, and there were other English editions in 1611 and 1686, as well as Spanish and French versions in the seventeenth century; so there was never any question of the work’s inaccessibility. Another account, by Luis Hernández de Biedma, remained unpublished until 1857, while that of de Soto’s secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, has never appeared except in severely abridged form. The most extensive work on the expedition, known as The Florida of the Inca, was written by a man born just a month before de Soto first set foot in Florida: Garcilaso de la Vega, known as “the Inca” because his mother, Chimpa Ocllo, had been a princess of Peru. (His father, Don Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega Vargas, had seen action with the Pizarros during the Spanish conquest of Peru.) Garcilaso, an attractive and complex figure who spent most of his life in Spain but who was fiercely proud of his royal Inca ancestry, published his book on de Soto at Lisbon in 1605. His chief sources were the oral recollections of an anonymous Spaniard who had marched with de Soto, and the crude manuscripts of two other eyewitnesses, Juan Coles and Alonso de Carmona.

From these Garcilaso wove a lengthy and vivid history, long thought to be largely fantastic, but now recognized as a trustworthy if somewhat romantic narrative. Its chief concern to us is the detailed descriptions it provides of Indian mounds of the Southeast.

De Soto had served with distinction in Peru. He fought bravely against the Incas, and acted as a moderating influence against some of the worst excesses of his fellow conquerors. The darkest action of that conquest-the murder of Atahuallpa, the Inca Emperor-took place without de Soto’s knowledge and despite his advice to treat the Inca courteously. He shared in the fabulous booty of Peru and in 1537 came home to Spain as one of the wealthies men in the realm. Seeking some tract of the New World that he could govern, he applied to the Spanish king, Charles V, for the region now known as Ecuador and Colombia. But Charles offered him instead the governorship of the vaguely defined territory of “Florida,” which had lapsed upon the disappearance of Pánfilo de Narvez. By the terms of a charter drawn up on April 20, 1537, de Soto obligated himself to furnish at least 500 men and to equip and supply them for a minimum of eighteen months.

In return, he would be made Governor of Cuba, and upon the conquest of Florida would have the rank of Adelantado of Florida, with a domain covering any two hundred leagues of the coast he chose. There he hoped to carve out a principality for himself as magnificent as that obtained by Cortés in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru.

In the midst of de Soto’s preparations, Cabeza de Vaca turned up in Mexico, and at last revealed the fate of Narvez’ expedition. De Soto invited Cabeza de Vaca to join his own party, but he had had enough of North America for a while, and went toward Brazil instead. De Soto collected men, sailed to Cuba, and recruited more men there. His reputation had preceded him from Peru; he was thought to have the Midas touch, and volunteers hastened to join him. He gathered 622 men in all, including a Greek engineer, an English longbowman, two Genoese, and four “dark men” from Africa. In April of 1539 they departed for Florida.

The expedition entered Tampa Bay a month later, and on May 30 de Soto’s soldiers began going ashore. Their object was to find a new kingdom as rich at Atahuallpa’s, and it seems strange that they would have begun the quest in the same country where Narváez had found only hardship and death.

From Mound Builders of Ancient America: Archaeology of a Myth (1968) by Robert Silverberg, who writes more vividly on de Soto than many a de Soto specialist. You can read all of the Gentleman of Elvas account here, it ain’t exactly Tom Clancy. Silberberg picks up:

had de Soto been gifted with second sight, he would have sounded the order for withdrawal at that moment, put his men back on board the ships, and returned to Spain to fondle his gold for the rest of his days. Thus he would have avoided the torments of a relentless, profitless, terrible march over 350,000 square miles of unexplored territory, and would have spared himself the early grave he found by the banks of the Mississippi. This was no land for conquerors. But a stroke of bad luck, in the guise of seeming fortune, drew de Soto remorselessly onward to doom. His scouts, while fighting off the Indian ambush, had been about to strike one naked Indian dead when he began to cry in halting Spanish, “Do not kill me, cavalier! I am a Christian!” He was Juan Ortiz of Seville, a marooned member of the Narvez expedition, who, since 1528, had lived among the Indians, adopting their customs, their language, and their garb. He could barely speak Spanish now, and he found the close-fitting Spanish clothes so uncomfortable that he went about de Soto’s camp in a long, loose linen wrap. He seemed precisely what de Soto needed: an interpreter, a guide to the undiscovered country that lay ahead.

Unhappily, Ortiz knew nothing of the country more than fifty miles from his own village, and each village seemed to speak a different language.

Nevertheless, the Spaniards proceeded north along Narvez’ route, looking for golden cities. Ortiz spoke to the Indians where he could and arranged peaceful passage through their territory. Where he could not communicate with them, the Spaniards employed cruelty to win their way—a cruelty that quickly became habitual and mechanical. The Indians were terrified of the Spaniards’ horses, for they had never seen such beasts before. With the Spaniards there came also packs of huge dogs, wolfhounds of ferocious mien.

Wolfhounds of ferocious mien.

That illustration, by Herb Roe, I find on de Soto’s Wikipedia page. Here’s a Herb Roe evocation of the Kincaid Site in Illinois:

Here is Herb Roe’s website.

Tampa’s on my mind today as its about the get wrecked by Hurricane Milton.

Prayers up for the Cigar City.

Source for that map of de Soto expedition is the Florida Historical Society. Winds tracker from earth.nullschool.net.

Related matters: Cahokia.

Mile Marker Zero: The Moveable Feast of Key West by William McKeen

Posted: September 24, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, Florida, Hemingway, writing Leave a comment

This is a book about a scene, and the scene was Key West in the late ’60s-’70s, centered on Thomas McGuane, Jim Harrison, Hunter Thompson, Jimmy Buffett, and some lesser known but memorable characters. I tried to think of other books about scenes, and came up with Easy Riders, Raging Bulls by Peter Biskind, and maybe Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 by Ryan H. Walsh, about Van Morrison’s Boston. Then of course there’s Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, referenced here in the subtitle, a mean-spirited but often beautiful book about 1920s Paris.

I was drawn to this book after I heard Walter Kirn talking about it on Bret Easton Ellis podcast (McGuane is Kirn’s ex-father-in-law, which must be one of life’s more interesting relationships). I’ve been drawn lately to books about the actual practicalities of the writing life. How do other writers do it? How do they organize their day? What time do they get to work? What do they eat and drink? How do they avoid distraction?

From this book we learn that Jim Harrison worked until 5pm, not 4:59 but 5pm, after which he cut loose. McGuane was more disciplined, even hermitish for a time (while still getting plenty of fishing done) but eventually temptation took over, he started partying with the boys, eventually was given the chance to direct the movie from his novel 92 In The Shade. That’s when things got really crazy. The movie was not a big success.

“The Sixties” (the craziest excesses bled well into the ’70s) musta really been something.

On page one of this book I felt there was an error:

That’s not the line. The line (from the Poetry Foundation) is:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ MenGang aft agley,

Part of what these writers found special about Key West, beyond the Hemingway and Tennessee Williams legends, was it just wasn’t a regular, straight and narrow place. Being a writer is a queer job, someone’s liable to wonder what it is you do all day. In Key West, that wasn’t a problem.

Key West was so irregular and libertine that you could get away with the apparent layaboutism of the writer’s life.

Some years ago I was writing a TV pilot I’d pitched called Florida Courthouse. I went down to Florida to do some research, and people kept telling me about Key West, making it sound like Florida’s Florida. Down I went on that fantastic drive where you feel like you’re flying, over Pigeon Key, surely one of the cooler drives in the USA if not the world.

The town I found at the end of the road was truly different. Louche, kind of disgusting, and there was an element of tourists chasing a Buffett fantasy. Some of the people I encountered seemed like untrustworthy semi-pirates, and some put themselves way out to help a stranger. You’re literally and figuratively way out there, halfway to Havana. The old houses, the chickens wandering, the cemetery, the heat and the shore and the breeze and the old fort and the general sense of license and liberty has an intoxicating quality. There was a slight element of forced fun, and trying to capture some spirit that may have existed mostly in legend. McKeen captures that aspect in his book:

Like McGuane, I found the mornings in Key West to be the best attraction. Quiet, promising, unbothered, potentially productive. Then in the afternoon you could go out and see what trouble was to be found. Somebody introduced me to a former sheriff of Key West, who helped me understand his philosophy of law enforcement: “look, you can’t put that much law on people if it’s not in their hearts.”

I enjoyed my time there in this salty beachside min-New Orleans and hope to return some day, although I don’t really think I’m a Key West person in my heart. I went looking for photos from that trip, and one I found was of the Audubon House.

After finishing this book I was recounting some of the stories to my wife and we put on Jimmy Buffett radio, and that led of course to drinking a bunch of margaritas and I woke up hungover.

I rate this book: four and a half margaritas.

Hemingway Writing Advice

Posted: November 13, 2017 Filed under: Florida, Hemingway, writing, writing advice from other people 2 Comments

one of the descendants of Hemingway’s messed-up, inbred, extra-toe cats in Key West

In a 1935 Esquire piece, Hemingway, already playing the preening dickhead, gives some writing advice that I think is clear-eyed and well-expressed.

Writing room in Hem house in Key West

The setup is a young man has come to visit him in Key West, and Hemingway has given him the nickname Maestro because he played the violin.

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise. Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Then get in somebody elseʼs head for a change If I bawl you out try to figure out what Iʼm thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Donʼt just think who is right. As a man things are as they should or shouldnʼt be. As a man you know who is right and who is wrong. You have to make decisions and enforce them. As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.

Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

Mice: Do you think I will be a writer?

Y.C.: How the hell should I know? Maybe youʼve got no talent. Maybe you canʼt feel for other people. Youʼve got some good stories if you can write them. Mice: How can I tell?

Y.C.: Write. If you work at it five years and you find youʼre no good you can just as well shoot yourself then as now.

Mice: I wouldnʼt shoot myself.

Y.C.: Come around then and Iʼll shoot you.

Mice: Thanks.

This article is behind a paywall at Esquire but I found it reprinted on the website of Diana Drake, who has story by credit on the film What Women Want.

Tennessee Williams -> Dr. Feelgood -> Mark Shaw

Posted: January 6, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, Florida, Kennedy-Nixon, writing 1 Comment

Tennessee Williams in Key West

Strewn around the apartment of a friend this weekend were a few biographies of Tennessee Williams.

I don’t know much about Tennessee Williams. The most I ever thought about him was when I was briefly in Key West, where there’s some stuff named after him. He jockeys with Hemingway for local literary mascot top honors.

Looking into it, I found this stupefying article about TW in Key West from People Magazine, 1979, entitled “In His Beloved Key West, Tennessee Williams Is Center Stage In A Furor Over Gays.” Tough reading, on the one hand. On the other maybe we can find some optimism in how far things have come?:

Some of Williams’ friends are less sanguine—notably Rader (whom some Key West sympathizers find faintly hysterical on the subject). “It has been terrible,” he said in the aftermath. “Tenn won’t talk about it, but it has been really frightening what’s happening in Key West and in this house. The worst was the night they stood outside his front porch and threw beer cans, shouting, ‘Come on out, faggot.’ When they set off the firecrackers, I remember thinking, ‘God, this is it. We’re under attack. They’ve started shooting.’ ”

Williams’ imperturbability springs both from a matter of principle (he once defined gallantry as “the grace with which one survives appalling experiences”) and from a diminished interest in the Key West gay scene. “I’ve retired from the field of homosexuality at present,” he explains, “because of age. I have no desires—isn’t that strange? I have dreams, but no waking interest.” The thought does not cheer him. “I’ve always found life unsatisfactory,” he says. “It’s unsatisfactory now, especially since I’ve given up sex.” His own problems seem far more pressing to him than the city’s. “I suspect I’ll only live another two years,” says Williams, 68, who tipples white wine from morning on and complains of heart and pancreas disorders. “I’ve been working like a son of a bitch since 1969 to make an artistic comeback. I don’t care about the money, but I can’t give up art—there’s no release short of death. It’s quite painful. I’ll be dictating on my deathbed. I want people to say, ‘Yes, this man is still an artist.’ They haven’t been saying it much lately.”

As a consummate prober of human passions, Williams does have theories on why his adopted hometown is under siege. “There are punks here,” he explains. “That’s because a couple of gay magazines publicized this place as if it were the Fire Island of Florida. It isn’t. One Fire Island is quite enough. But it attracted the wrong sort of people here: the predators who are looking for homosexuals. I think the violence will be gone by next year.”

Other residents seem less willing to wait. The leader of the anti-gay forces, the Reverend Wright, says Anita Bryant has promised to come to Key West to help his crusade. Recalling nostalgically the days when “female impersonators and queers were loaded into a deputy’s automobile and shipped to the county line,” Wright warns: “We’ll either have a revival of our society or the homosexuals will take it over in five years.”

Mamet On Williams

This morning happened to pick up in my garage this book by David Mamet:

Highly recommend this book as well as Three Uses Of The Knife, True And False: Heresy And Common Sense For The Actor, and On Directing Film by Mamet. All short, all tight, all good. (His subsequent nonfiction seems to me to be a bit… deranged?)

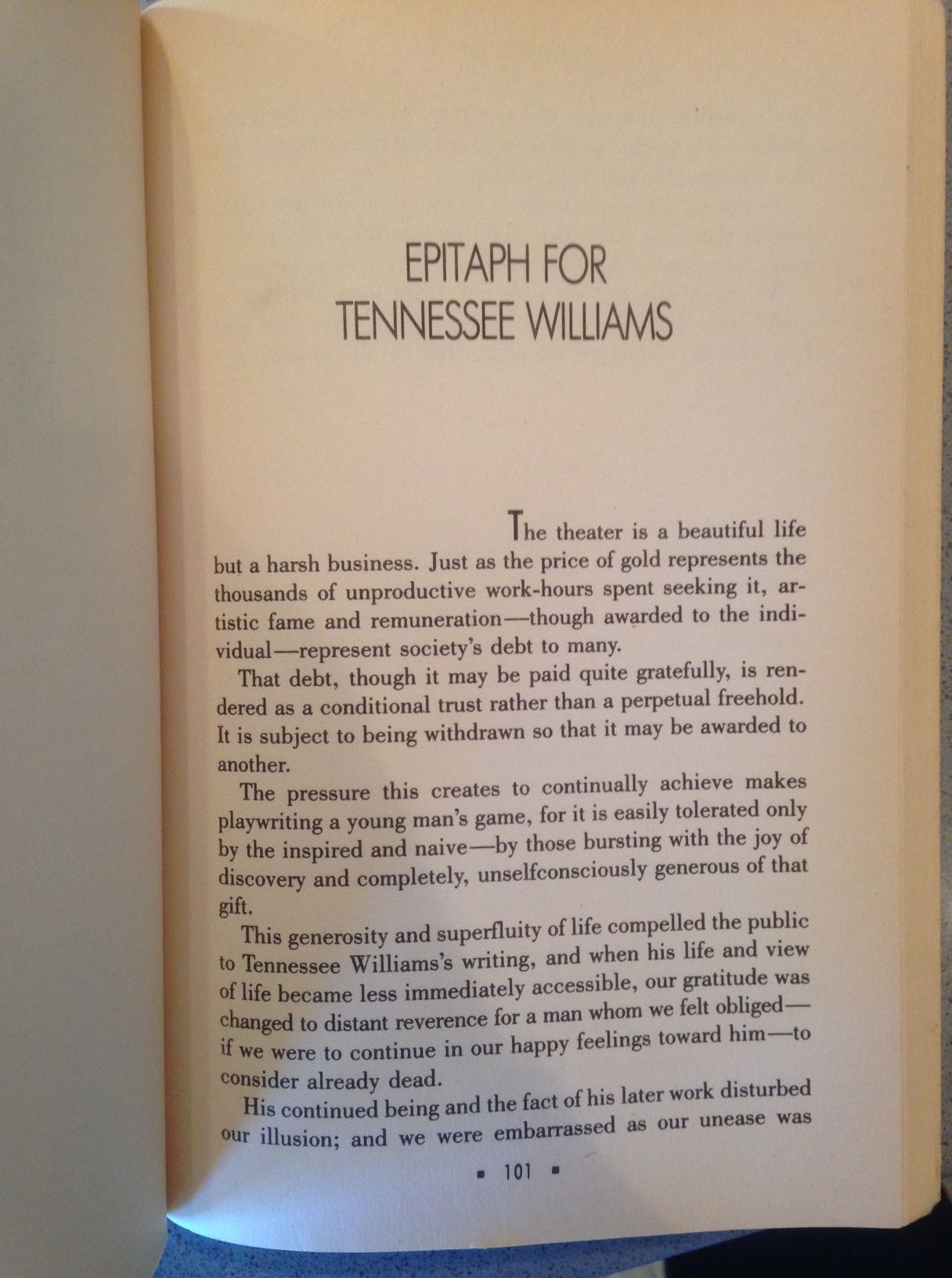

Found this, and thought it was great:

Wikipedia Hole

Reading about Tennessee on Wikipedia, I learn:

As he had feared, in the years following Merlo’s death Williams was plunged into a period of nearly catatonic depression and increasing drug use resulting in several hospitalizations and commitments to mental health facilities. He submitted to injections by Dr. Max Jacobson – known popularly as Dr. Feelgood – who used increasing amounts of amphetamines to overcome his depression and combined these with prescriptions for the sedative Seconal to relieve his insomnia. Williams appeared several times in interviews in a nearly incoherent state, and his reputation both as a playwright and as a public personality suffered.[citation needed] He was never truly able to recoup his earlier success, or to entirely overcome his dependence on prescription drugs.

Let’s learn about Dr. Feelgood, who was also screwing up Elvis and everybody else cool back then:

John F. Kennedy first visited Jacobson in September 1960, shortly before the 1960 presidential election debates.[9] Jacobson was part of the Presidential entourage at the Vienna summit in 1961, where he administered injections to combat severe back pain. Some of the potential side effects included hyperactivity, impaired judgment, nervousness, and wild mood swings. Kennedy, however, was untroubled by FDA reports on the contents of Jacobson’s injections and proclaimed: “I don’t care if it’s horse piss. It works.”[10] Jacobson was used for the most severe bouts of back pain.[11] By May 1962, Jacobson had visited the White House to treat the President thirty-four times.[12][13]

By the late 1960s, Jacobson’s behavior became increasingly erratic as his own amphetamine usage increased. He began working 24-hour days and was seeing up to 30 patients per day. In 1969, one of Jacobson’s clients, former Presidential photographer Mark Shaw, died at the age of 47. An autopsy showed that Shaw had died of “acute and chronic intravenous amphetamine poisoning.”

Well, that takes us to

Mark Shaw

Born Mark Schlossman on the Lower East Side, a pilot on the India/China Hump in World War II, he became a freelance photographer for life:

In 1953, probably because of his fashion experience, Shaw was assigned to photograph the young actress Audrey Hepburn during the filming of Paramount’s Sabrina. Evasive at first, Hepburn became comfortable with Shaw’s presence over a two-week period and allowed him to record many of her casual and private moments.

He married singer Pat Suzuki, “who is best known for her role in the original Broadway production of the musical Flower Drum Song, and her performance of the song “I Enjoy Being a Girl” in the show”:

In 1959, Life chose Shaw to photograph Jacqueline Kennedy while her husband, Senator John F. Kennedy, was running for President.[8] This assignment was the beginning of an enduring working relationship and personal friendship with the Kennedys that would eventually lead to Shaw’s acceptance as the Kennedys’ de facto “family photographer”. He visited them at theWhite House and at Hyannisport; during this time he produced his most famous photographs, portraying the couple and their children in both official and casual settings. In 1964, Shaw published a collection of these images in his book The John F. Kennedys: A Family Album, which was very successful.

A bunch of even better ones can be found here, at the tragically disorganized website of the Monroe Gallery, they’re stamped “No Reproduction Without Permission” so whatever. Don’t miss this one.

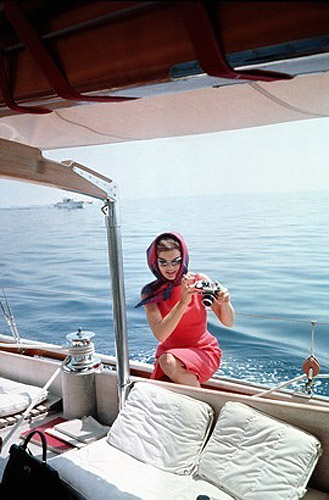

Here’s another famous Jackie Mark photo’d:

And finally: