William Faulkner’s introduction to Sanctuary

Posted: December 31, 2023 Filed under: memphis, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentThe best character William Faulkner ever created was himself, William Faulkner. The flying injury, Rowan Oak, the photographs, the guest roles, the interviews, scraps of footage, the Nobel Prize speech. Perfect.

In 1929 William Faulkner, then age 31, wrote Sanctuary, which has one of the trashiest loglines ever: Ole Miss coed Temple Drake ends up the sex slave of a gangster named Popeye. Here at Helytimes we won’t go into detail of what exactly Popeye does, we leave that to lesser publications like The Washington Post:

what interested him chiefly about this horrific event was “how all this evil flowed off her like water off a duck’s back.” In his haste to make a best seller, he crammed in all he had seen and heard about whorehouses, rapes and kidnappings.

This was a ripped from the headlines story based on a true crime case. As a Mississippi crime book complete with courtroom scenes, it’s kind of a proto-Grisham.

Sanctuary was published by Jonathan Cape in 1931. Then in 1932 the Modern Library put out a new edition with a new introduction by Faulkner. Scholars since have apparently debunked everything Faulkner claimed in this introduction as fabulations and lies but so what? In a way that makes it even better. A work of autofiction.

We couldn’t find this introduction online so we got a used copy and scanned it in, it’s out of copyright (we believe?).

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN THREE YEARS AGO. To me it is a cheap idea, because it was deliberately conceived to make money. I had been writing books for about five years, which got published and not bought. But that was all right. I was young then and hard-bellied. I had never lived among nor known people who wrote novels and stories and I suppose I did not know that people got money for them. I was not very much annoyed when publishers refused the mss. now and then. Because I was hard-gutted then. I could do a lot of things that could earn what little money I needed, thanks to my father’s un- failing kindness which supplied me with bread at need despite the outrage to his principles at having been of a bum progenitive.

Then I began to get a little soft. I could still paint houses and do carpenter work, but I got soft. I began to think about making money by writing. I began to be concerned when magazine editors turned down short stories, concerned enough to tell them that they would buy these stories later anyway, and hence why not now. Meanwhile, with one novel completed and consistently refused for two years, I had just written my guts into The Sound and the Fury though I was not aware until the book was pub- lished that I had done so, because I had done it for pleasure. I believed then that I would never be published again. I had stopped thinking of myself in publishing terms.

But when the third mss., Sartoris, was taken by a publisher and (he having refused The Sound and the Fury) it was taken by still another publisher, who warned me at the time that it would not sell, I began to think of myself again as a printed object. I began to think of books in terms of possible money. I decided I might just as well make some of it myself. I took a little time out, and speculated what a person in Mississippi would believe to be current trends, chose what I thought was the right answer and invented the most horrific tale I could imagine and wrote it in about three weeks and sent it to Smith, who had done The Sound and the Fury and who wrote me immediately. ”Good God, I can’t publish this. We’d both be in jail.” So I told Faulkner, “You’re damned. You’ll have to work now and then for the rest of your life.” That was in the summer of 1929. I got a job in the power plant, on the night shift, from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M., as a coal passer. I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheel- barrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler. About 11 o’clock the people wuuld be going to bed, and so it did not take so much steam. Then we could rest, the fireman and I. He would sit in a chair and doze. I had invented a table out of a wheel- barrow in the coal bunker, just beyond a wall from where a dynamo ran. It made a deep, constant humming noise. There was no more work to do until about 4 A.M., when we would have to clean the fires and get up steam again. On these nights, between 12 and 4, I wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks, without changing a word. I sent it to Smith and wrote him that by it I would stand or fall.

I think I had forgotten about Sanctuary, just as you might forget about anything made for an immediate purpose, which did not come off. As I Lay Dying was published and I didn’t remember the mss. of Sanctuary until Smith sent me the galieys. Then I saw that it was so terrible that there were but two things to do: tear it up or rewrite it. I thought again, “It might sell; maybe 10,000 of them will buy it.” So I tore the galleys down and rewrote the book. It had been already set up once, so I had to pay for the

privilege of rewriting it, trying to make out of it something which would not shame The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying too much and I made a fair job and I hope you will buy it and tell your friends and I hope they will buy it too.WILLIAM FAULKNER. New York, 1932.

Happy New Year to all 6,722 of our loyal readers, all over the globe.

The Golden West: Hollywood Stories, by Daniel Fuchs

Posted: August 14, 2022 Filed under: Hollywood, the California Condition, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentCritics and bystanders who concern themselves with the plight of the Hollywood screenwriter don’t know the real grief that goes with the job. The worst is the dreariness in the dead sunny afternoons when you consider the misses, the scripts you’ve labored on and had high hopes for and that wind up on the shelf, when you think of the mountains of failed screenplays on the shelf at the different movie companies…

brother, I hear you, but also c’mon, it beats working for a living.

An old-timer in the business, a sweet soul of other days, drops into my room. “Don’t be upset,” he says, seeing my face. “They’re not shooting the picture tomorrow. Something will turn up. You’ll revise.” I ask him what in his opinion there is to write, what does he think will make a good picture. He casts back in his mind to ancient successes, on Broadway and on film, and tries to help me out. “Well, to me, for an example – now this might sometimes come in handy – it’s when a person is trying to do something to another person, and the second fellow all the time is trying to do it to him, and they both of them don’t know.” Another man has once told me the secret of motion picture construction: “A good story, for the houses, it’s when the ticket buyer, if he should walk into the theater in the middle of the picture – he shouldn’t get confused but know pretty soon what’s going on.” “The highest form of art is a man and a woman dancing together,” still a third man has told me.

authenticity / domain expertise

Posted: June 29, 2022 Filed under: Uncategorized, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Have been mulling over Paul Graham’s statement here: does this apply to all writing? Think on the compelling novels. Don’t they usually combine authenticity and domain expertise? Even if the domain expertise is gained by a passionate amateur, as in Tom Clancy.

Last terrific novel I read was Elif Batuman’s Either/Or: authenticity and domain (Harvard, literary studies, sexual trauma) expertise? Check and check on that one.

Or here’s John Grisham:

I read a lot of books written by other lawyers–legal thrillers, as they are called–I read them because I enjoy them, also I have to keep an eye on the competition. I can usually tell by page three if the author has actually been in a fight in a courtroom, or whether he’s simply watched too much television.

(Grisham in that speech itemizes three essential elements of voice: clarity, authenticity, and veracity).

Or how about Ellison on Hemingway‘s authenticity and domain expertise:

when he describes something in print, believe him

Somewhere Shelby Foote said that the reason his Ken Burns interviews were compelling was simply that he knew what he was talking about, he’d been thinking, reading, writing about the Civil War for twenty years. (He still got some stuff wrong).

Is it that simple? Is the key to writing just 1) being genuine and 2) knowing what you’re talking about?

Gotta work on this.

method

Posted: February 5, 2022 Filed under: actors, Hemingway, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentIn one famous Brando origin story, Adler asked her students to pretend to be chickens as an atomic bomb drops. While everyone else was flapping in a panic, Brando peaceably squatted down. “I’m laying an egg,” he told Adler. “What does a chicken know of bombs?”

reading Alexandra Schwartz on Isaac Butler’s book about method acting in The New Yorker. A shifting concept, perhaps we can agree?

“the Method” is describes a set of techniques, practices, and concepts for helping actors achieve emotional life and truth in their performances. The Method is based on the teachings of Stanislavski, developed at the Moscow Art Theater, interpreted in the United States by teachers like Lee Strasburg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner and by actors like Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe.

Defining things is hard, I’m already quibbling with myself!

Maybe Wikipedia’s is better, Wikipedia really is a miracle, isn’t it folks? Sainthood for Jimmy Wales.

Some of what the Method seems to get at, like chunks of reality, precision of memory, the blend of emotional and physical experience, reminded me of Hemingway on focusing as specifically as possible on the connection of sensation to specific detail. What did you feel, what exactly made you feel it in the moment?

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise.

…

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

more on that.

action vs adventure

Posted: January 4, 2022 Filed under: adventures, writing advice from other people Leave a comment“I have a definition of what I do,” Wolpert told the WGAW in 2008. “If you put a boat on the stormy ocean, you’ve got an action picture. You put somebody on that boat you give a damn about, you’ve got an adventure. I write adventure.”

from this Deadline obituary for writer/producer Jay Wolpert.

Conversations with Faulkner

Posted: September 7, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, Hollywood, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Alcohol was his salve against a modern world he saw as a conspiracy of mediocrity on its ruling levels. Life was most bearable, he repeated, at its simplest: fishing, hunting, talking biggity in a cane chair on a board sidewalk, or horse-trading, gossiping.

Bill spoke rarely about writing, but when he did he said he had no method, no formula. He started with some local event, a well-known face, a sudden reaction to a joke or an incident. “And just let the story carry itself. I walk along behind and write down what happens.”

Origin story:

Q: Sir, I would like to know exactly what it was that inspired you to become a writer.

A: Well, I probably was born with the liking for inventing stories. I took it up in 1920. I lived in New Orleans, I was working for a bootlegger. He had a launch that I would take down the Pontchartrain into the gulf to an island where the run, the green rum, would be brought up from Cuba and buried, and we would dig it up and bring it back to New Orleans, and he would make scotch or gin or whatever he wanted. He had the bottles labeled and everything. And I would get a hundred dollars a trip for that, and I didn’t need much money, so I would get along until I ran out of money again. And I met Sherwood Anderson by chance, and we took to each other from the first. I’d meet him in the afternoon, we would walk and he would talk and I would listen. In the evening we would go somewhere to a speakeasy and drink, and he would talk and I would listen. The next morning he would say, “Well I have to work in the morning,” so I wouldn’t see him until the next afternoon. And I thought if that’s the sort of life writers lead, that’s the life for me. So I wrote a book and, as soon as I started, I found out it was fun. And I hand’t seen him and Mrs. Anderson for some time until I met her on the street, and she said, “Are you mad at us?” and I said, “No, ma’am, I’m writing a book,” and she said, “Good Lord!” I saw her again, still having fun writing the book, and she said, “Do you want Sherwood to see your book when you finish it?” and I said, “Well, I hadn’t thought about it.” She said, “Well, he will make a trade with you; if he don’t have to read that book, he will tell his publisher to take it.” I said, “Done!” So I finished the book and he told Liveright to take it and Liveright took it. And that was how I became a writer – that was the mechanics of it.

Stephen Longstreet reports on Faulkner in Hollywood, specifically To Have and Have Not:

Several other writers contributed, but Bill turned out the most pages, even if they were not all used. This made Bill a problem child.

The unofficial Writers’ Guild strawboss on the lot came to me.

“Faulkner is turning out too many pages. He sits up all night sometimes writing and turns in fifty to sixty pages in the morning. Try and speak to him.”

Conversations With series from the University Press of Mississippi

Posted: August 31, 2020 Filed under: advice, America Since 1945, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment This is one my favorite books, I’m serious. Shelby Foote is a great interview, obviously, just watch his interviews with Ken Burns. (“Ken, you made me a millionaire,” Shelby reports telling Burns after the series aired.) You may not want to read the whole of Shelby’s three volume Civil War, it can get carried away with the lyrical, and following the geography can be a challenge. But the flavor of it, some of the most vivid moments, and anecdotes, come through in these collected conversations with inquirers over the years.

This is one my favorite books, I’m serious. Shelby Foote is a great interview, obviously, just watch his interviews with Ken Burns. (“Ken, you made me a millionaire,” Shelby reports telling Burns after the series aired.) You may not want to read the whole of Shelby’s three volume Civil War, it can get carried away with the lyrical, and following the geography can be a challenge. But the flavor of it, some of the most vivid moments, and anecdotes, come through in these collected conversations with inquirers over the years.

“You’ve got to remember that the Civil War was as big as life,” he explains. “That’s why no historian has ever done it justice, or ever will. But that’s the glory of it. Take me: I was raised up believing Yankees were a bunch of thieves. But it’s absolutely incredible that a people could fight a Civil War and have so few atrocities.

“Sherman marched with 60,000 men slap across Georgia, then straight up though the Carolinas, burning, looting, doing everything in the world – but I don’t know of a single case of rape. That’s amazing because hatreds run high in civil wars…

There were still a lot of antique virtues around them. Jackson once told a colonel to advance his regiment across a field being riddled by bullets. When the officer protested that nobody could survive out there, Jackson told him he always took care of his wounded and buried his dead. The colonel led his troops into the field.”

Finally treated myself to a few more of these editions. These books are casual and comfortable. They’re collections of interviews from panels, newspapers, magazines, literary journals, conference discussions. Physically they’re just the right size, the printing is quality and the typeface is appealing.

Why not start with another Mississippian, someone Foote had quite a few conversations with himself?

Wow, Walker Percy could converse.

Later, different interview:

Do we dare attempt conversation with the father of them all?

I’ve long found interviews with Faulkner, even stray details from the life of Faulkner, to be more compelling than his fiction. Maybe it’s the appealing lifestyle: courtly freedom, hunting, fishing, and all the whiskey you can handle. The life of an unbothered country squire, preserving a great tradition, going to Hollywood from time to time, turning the places of your boyhood into a world mythology.

We’ll have more to say about the Conversations with Faulkner, deserves its own post! Maybe Percy gets to the heart of it in one of his interviews:

Q: Did you serve a long apprenticeship in becoming a writer?

Percy: Well, I wrote a couple of bad novels which no one wanted to buy. And I can’t imagine anyboy doing anything else. Yes it was a long apprenticeship with some frustration. But I was lucky with the third one, The Moviegoer; so, it wasn’t so bad, I guess.

Q: Had you rather be a writer than a doctor?

Percy: Let’s just say I was the happiest doctor who ever got tuberculosis and was able to quit it. It gave me an excuse to do what I wanted to do. I guess I’m like Faulkner in that respect. You know Faulkner lived for awhile in the French Quarter of New Orleans where he met Sherwood Anderson, and Faulkner used to say if anybody could live like that and get away with it he wanted to live the same way.

There’s one of these for you, I’m sure. They also have Comic Artists and Filmmakers.

only one subject with whom I myself had a conversation

For the advanced student:

The people in the next booth

Posted: August 9, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing advice from other people Leave a commentMAMET

I never try to make it hard for the audience. I may not succeed, but . . . Vakhtangov, who was a disciple of Stanislavsky, was asked at one point why his films were so successful, and he said, Because I never for one moment forget about the audience. I try to adopt that as an absolute tenet. I mean, if I’m not writing for the audience, if I’m not writing to make it easier for them, then who the hell am I doing it for? And the way you make it easier is by following those tenets: cutting, building to a climax, leaving out exposition, and always progressing toward the single goal of the protagonist. They’re very stringent rules, but they are, in my estimation and experience, what makes it easier for the audience.

INTERVIEWER

What else? Are there other rules?

MAMET

Get into the scene late, get out of the scene early.

INTERVIEWER

Why? So that something’s already happened?

MAMET

Yes. That’s how Glengarry got started. I was listening to conversations in the next booth and I thought, My God, there’s nothing more fascinating than the people in the next booth. You start in the middle of the conversation and wonder, What the hell are they talking about? And you listen heavily. So I worked a bunch of these scenes with people using extremely arcane language—kind of the canting language of the real-estate crowd, which I understood, having been involved with them—and I thought, Well, if it fascinates me, it will probably fascinate them too. If not, they can put me in jail.

from The Paris Review of course.

Really missing overhearing the people in the next booth these days. Feeling the loss of the scuttlebutt. The collective vibecheck you get from what the people you overhear in the coffeeshop, see in the elevator at work. The tide is out on that kind of info, the shared hum. When it comes back in, perceptions will change. Understandings will be recalibrated. Was wondering how this in particular with the stock market, which moves with this mood. We may find out soon!

The Evolution of Pace In Popular Movies

Posted: December 29, 2018 Filed under: film, movies, screenwriting, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Abstract

Movies have changed dramatically over the last 100 years. Several of these changes in popular English-language filmmaking practice are reflected in patterns of film style as distributed over the length of movies. In particular, arrangements of shot durations, motion, and luminance have altered and come to reflect aspects of the narrative form. Narrative form, on the other hand, appears to have been relatively unchanged over that time and is often characterized as having four more or less equal duration parts, sometimes called acts – setup, complication, development, and climax. The altered patterns in film style found here affect a movie’s pace: increasing shot durations and decreasing motion in the setup, darkening across the complication and development followed by brightening across the climax, decreasing shot durations and increasing motion during the first part of the climax followed by increasing shot durations and decreasing motion at the end of the climax. Decreasing shot durations mean more cuts; more cuts mean potentially more saccades that drive attention; more motion also captures attention; and brighter and darker images are associated with positive and negative emotions. Coupled with narrative form, all of these may serve to increase the engagement of the movie viewer.

Keywords: Attention, Emotion, Evolution, Film style, Movies, Narrative, Pace, Popular culture

Over at Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, James E. Cutting has an interesting paper about how popular movies have changed over time in terms of shot duration, motion, luminance, and cuts.

One thing that hasn’t really changed though: a three or four act structure.

In many cases, and particularly in movies, story form can be shown to have three or four parts, often called acts (Bordwell, 2006; Field, 2005; Thompson, 1999). The term act is borrowed from theater, but it does not imply a break in the action. Instead, it is a convenient unit whose size is between the whole film and the scene in which certain story functions occur. Because there is not much difference between the three- and four-act conceptions except that the latter has the former’s middle act broken in half (which many three-act theorists acknowledge; Field, 2005), I will focus on the four-act version.

The first act is the setup, and this is the portion of the story where listeners, readers, or viewers are introduced to the protagonist and other main characters, to their goals, and to the setting in which the story will take place. The second act is the complication, where the protagonists’ original plans and goals are derailed and need to be reworked, often with the help or hindrance of other characters. The third is the development, where the narrative typically broadens and may divide into different threads led by different characters. Finally, there is the climax, where the protagonist confronts obstacles to achieve the new goal, or the old goal by a different route. Two other small regions are optional bookend-like structures and are nested within the last and the first acts. At the end of the climax, there is often an epilogue, where the diegetic (movie world) order is restored and loose ends from subplots are resolved. In addition, I have suggested that at the beginning of the setup there is often a prologue devoted to a more superficial introduction of the setting and the protagonist but before her goals are introduced (Cutting, 2016).

Interesting way to think about film structure. Why are movies told like this?

Perhaps most convincing in this domain is the work by Labov and Waletzky (1967), who showed that spontaneous life stories elicited from inner-city individuals without formal education tend to have four parts: an orientation section (where the setting and the protagonist are introduced), a complication section (where an inciting incident launches the beginning of the action), an evaluation section (which is generally focused on a result), and a resolution (where an outcome resolves the complication). The resolution is sometimes followed by a coda, much like the epilogue in Thompson’s analysis. In sum, although I wouldn’t claim that four-part narratives are universal to all story genres, they are certainly widespread and long-standing

Cutting goes on:

That form entails at least three, but usually four, acts of roughly equal length. Why equal length? The reason is unclear, but Bordwell (2008, p. 104) suggested this might be a carryover from the development of feature films with four reels. Early projectionists had to rewind each reel before showing the next. Perhaps filmmakers quickly learned that, to keep audiences engaged, they had to organize plot structure so that last-seen events on one reel were sufficiently engrossing to sustain interest until the next reel began.

David Bordwell:

source: Wasily on Wiki

I love reading stuff like this, in the hopes of improving my craft at storytelling, but as Cutting notes:

Filmmaking is a craft. As a craft, its required skills are not easily penetrated in a conscious manner.

In the end you gotta learn by feel. We can feel when a story is right, or when it’s not right. I reckon you can learn more about movie story, and storytelling in general, by telling your story to somebody aloud and noticing when you “lose” them than you can by reading all of Brodwell. Anyone who’s pitched anything can probably remember moments when you knew you had them, or spontaneously edited because you could feel you were losing them.

Still, it’s fun to break apart human cognition and I look forward to more articles from Cognitive Science and am grateful they are free!

Another paper cited in this article is “You’re a good structure, Charlie Brown: the distribution of narrative categories in comic strips” by N Cohn.

Thanks to Larry G. for putting me on to this one.

Cowen and Taleb (and Norm)

Posted: December 2, 2018 Filed under: jesus, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentIt’s like we understand that we’re not in here to eat mozzarella and go to Tuscany. We’re not in here to accumulate money. We’re in here mostly to sacrifice, to do something. The way you do it is by taking risks.

It’s taking risks for the sake of becoming more human. Like Christ. He took risks and he suffered. Of course, it was a bad outcome, but you don’t have to go that far. That was the idea.

More:

TALEB: Before 15, and I reread it many times. I’d say, before 15, I read Dostoyevsky and I read The Idiot. There’s a scene that maybe I was 14 when I read it. Prince Myshkin was giving this story. Actually, it was autobiographical for Dostoyevsky.

He said he was going to be put to death. As they woke him up and were taking him to the execution place, he decided to live the last few minutes of his life with intensity. He devoured life, it was so pleasurable, and promised himself, if he survives, to enjoy every minute of life the same way.

And he survived. In fact, it was a simulacrum of an execution, and Dostoyevsky . . . effectively that says the guy survived. The lesson was he no longer did that. It was about the preferences of the moment. He couldn’t carry on later. He forgot about the episode. That marked me from Dostoyevsky when I was a kid, and then became obsessed with Dostoyevsky.

More:

I discovered that I wanted to be a writer as a kid. I realized to have an edge as a writer, you can’t really know what people know. You’ve got to know a lot of stuff that they don’t know.

Also re: Jesus, how about Norm Macdonald on the topic:

Writing Course from Stephen J. Cannell

Posted: September 14, 2018 Filed under: TV, writing, writing advice from other people 2 Comments

Our friends over at Monkey Trial put this one up. Led us to the Stephen J. Cannell website, where there’s a short but thorough and helpful writing course available for free. Adding it to my category Writing Advice From Other People.

What is a story? What is narrative?

Posted: August 19, 2018 Filed under: writing, writing advice from other people 1 Comment

“Good story” means something worth telling that the world wants to hear. Finding this is your lonely task. It begins with talent… But the love of a good story, of terrific characters and a world driven by your passion, courage, and creative gifts is still not enough. Your goal must be a good story well told.

says McKee.

What is a story? What makes something a story? It’s a question of personal and professional interest here at Helytimes. The dictionary gives me this for narrative:

a spoken or written account of connected events; a story.

boldface mine.

The human brain is wired to look for patterns and connections. Humans think in stories and seem to prefer a story, even a troubling story, to random or unrelated events. This can trick us as well as bring us wisdom and pleasure.

Nicholas Nassem Taleb discusses this in The Black Swan:

Narrative is a way to compress and store information.

From some investing site or Twitter or something, I came across this paper:

“Cracking the enigma of asset bubbles with narratives,” by Preston Teeter and Jörgen Sandberg in Strategic Organization. You can download a PDF for free.

Teeter and Sandberg suggest that “mathematical deductivist models and tightly controlled, reductionist experiments” only get you so far in understanding asset bubbles. What really drives a bubble is the narrative that infects and influences investors.

Clearly, under such circumstances, individuals are not making rational, cool-headed decisions based upon careful and cautious fundamental analysis, nor are their decisions isolated from the communities in which they live or the institutions that govern their lives. As such, only by incorporating the role of narratives into our research efforts and theoretical constructs will we be able to make substantial progress toward better understanding, predicting, and preventing asset bubbles.

Cool! But, of course, we need a definition of narrative:

But first, in order to develop a more structured view of how bubbles form, we also need a means of identifying the structural features of the narratives that emerge before, during, and after asset bubbles. The most widely used method of evaluating the structural characteristics of a narrative is that based on Formalist theories (see Fiol, 1989; Hartz and Steger, 2010; Pentland, 1999; Propp, 1958). From a structural point of view, a narrative contains three essential elements: a “narrative subject,” which is in search of or destined for a certain object; a “destinator” or source of the subject’s ideology; and a set of “enabling and impeding forces.” As an example of how to operationalize these elements, consider the following excerpt from another Greenspan (1988) speech:

More adequate capital, risk-based capital, and increased securities powers for bank holding companies would provide a solid beginning for our efforts to ensure financial stability. (p. 11)

OK great. Let’s get to the source here. Fiol, Hartz and Steger, and Pentland are all articles about “narrative” in business settings. Propp is the source here. Propp is this man:

Vladimir Propp, a Soviet analyst of folktales, and his book is this:

I’ve now examined this book, and find it mostly incomprehensible:

Propp’s 31 functions (summarized here on Wikipedia) are pretty interesting. How a Soviet theorist would feel about his work on Russian folktales being used by Australian economists to assess asset bubbles in capitalist markets is a fun question. Maybe he’d be horrified, maybe he’d be delighted. Perhaps he’d file it under Function 6:

TRICKERY: The villain attempts to deceive the victim to acquire something valuable. They press further, aiming to con the protagonists and earn their trust. Sometimes the villain make little or no deception and instead ransoms one valuable thing for another.

There’s some connection here to Dan Harmon’s story circles.

But when it comes to the definition of what makes a story go, I like the blunter version, expressed by David Mamet in this legendary memo to the writers of The Unit::

QUESTION:WHAT IS DRAMA? DRAMA, AGAIN, IS THE QUEST OF THE HERO TO OVERCOME THOSE THINGS WHICH PREVENT HIM FROM ACHIEVING A SPECIFIC, *ACUTE* GOAL.

SO: WE, THE WRITERS, MUST ASK OURSELVES *OF EVERY SCENE* THESE THREE QUESTIONS.

1) WHO WANTS WHAT?

2) WHAT HAPPENS IF HER DON’T GET IT?

3) WHY NOW?

Cracking the enigma of narrative is a fun project.

ps don’t talk to me about Aristotle unless you’ve REALLY read The Poetics.

Interview: John Levenstein

Posted: July 22, 2018 Filed under: writing, writing advice from other people 2 CommentsThe hardest part is just getting it out

Posted: May 31, 2018 Filed under: writing, writing advice from other people 1 Comment I consider myself a Sierra Ornelas fan but I would’ve missed this interview with her in Creative Independent had I not caught it over at Bookbinderlocal455

I consider myself a Sierra Ornelas fan but I would’ve missed this interview with her in Creative Independent had I not caught it over at Bookbinderlocal455

source

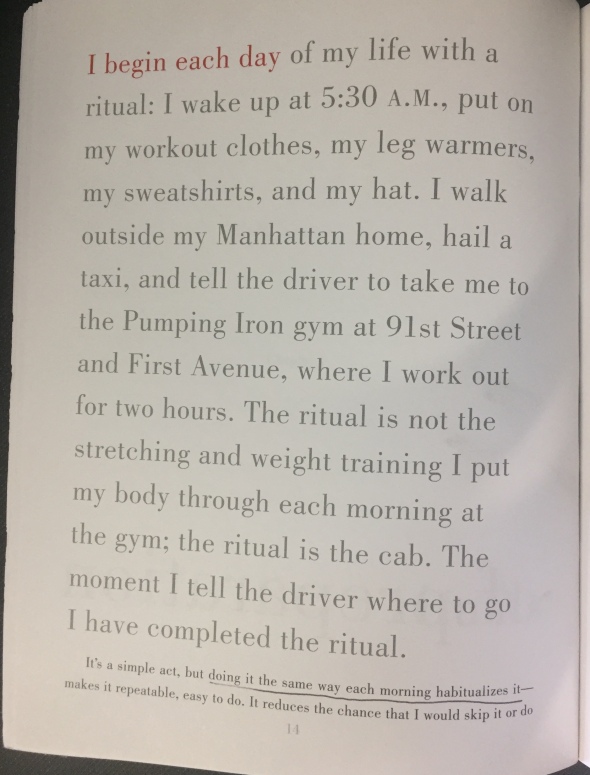

Similar advice is given at the beginning of this book:

which I found really helpful. The jist being: make it as easy as possible, even automatic, to start creative work.

The starting is the hard part.

Hemingway Writing Advice

Posted: November 13, 2017 Filed under: Florida, Hemingway, writing, writing advice from other people 2 Comments

one of the descendants of Hemingway’s messed-up, inbred, extra-toe cats in Key West

In a 1935 Esquire piece, Hemingway, already playing the preening dickhead, gives some writing advice that I think is clear-eyed and well-expressed.

Writing room in Hem house in Key West

The setup is a young man has come to visit him in Key West, and Hemingway has given him the nickname Maestro because he played the violin.

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise. Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Then get in somebody elseʼs head for a change If I bawl you out try to figure out what Iʼm thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Donʼt just think who is right. As a man things are as they should or shouldnʼt be. As a man you know who is right and who is wrong. You have to make decisions and enforce them. As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.

Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

Mice: Do you think I will be a writer?

Y.C.: How the hell should I know? Maybe youʼve got no talent. Maybe you canʼt feel for other people. Youʼve got some good stories if you can write them. Mice: How can I tell?

Y.C.: Write. If you work at it five years and you find youʼre no good you can just as well shoot yourself then as now.

Mice: I wouldnʼt shoot myself.

Y.C.: Come around then and Iʼll shoot you.

Mice: Thanks.

This article is behind a paywall at Esquire but I found it reprinted on the website of Diana Drake, who has story by credit on the film What Women Want.