Nebraska: Springsteen and Starkweather

Posted: October 30, 2025 Filed under: music Leave a comment

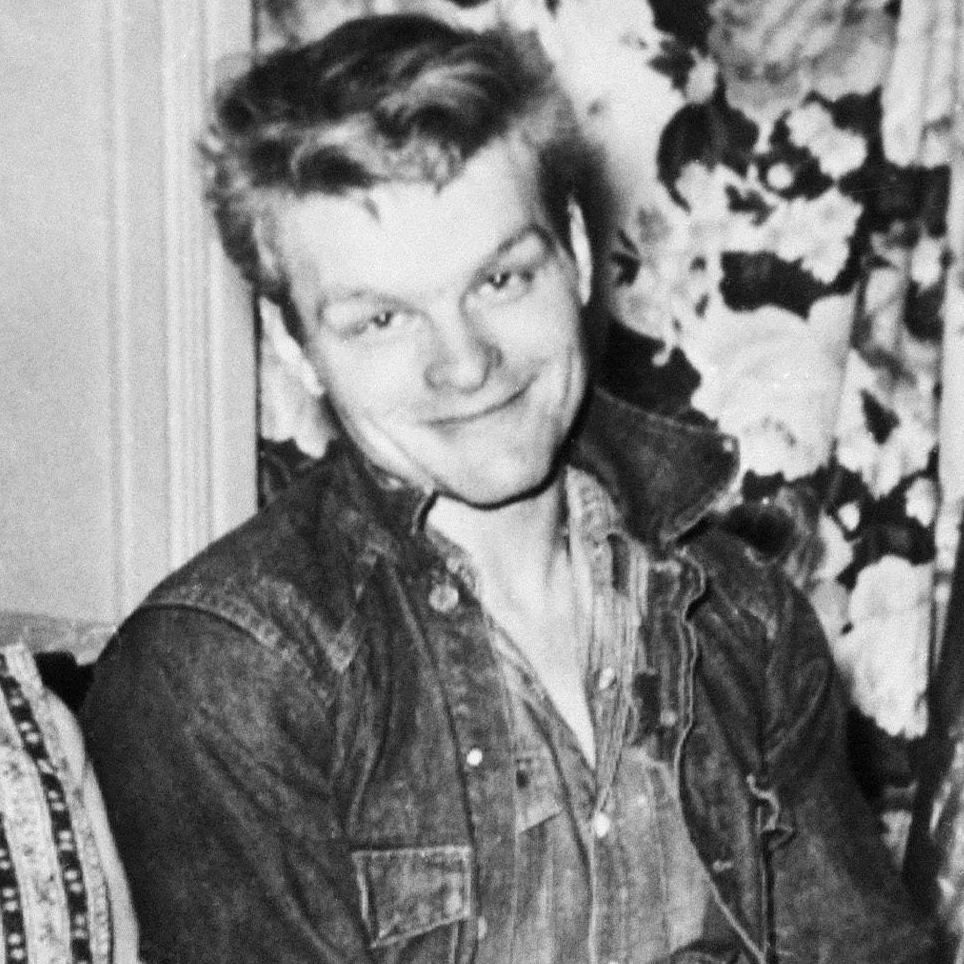

watching Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere has me thinking about Charlie Starkweather, the spree killer inspiration for the role played by Martin Sheen in Badlands, shown in the film as stimulating Bruce’s imagination for the song and album Nebraska.

Larry McMurtry, in Roads, says:

Kids in the midwest only get to see even modest levels of glamour if they happen to be on school trips to one or another of the midwestern cities: K.C., Omaha, St. Louis, the Twin Cities. In some, clearly, this lack of glamour festers. Charles Starkweather, in speaking about his motive for killing all those people, had this to say: “I never ate in a high-class restaurant, I never seen the New York Yankees play, I never been to Los Angeles…”

I put Perplexity AI on the job of sourcing that quote, and it gave up in failure:

The phrase you provided—”I never ate in a high-class restaurant, I never seen the New York Yankees play, I never been to Los Angeles…”—does not appear in any published 1958 interview transcript or Nebraska prison record in major archival listings. Summaries of Starkweather’s statements, including interrogation by Lancaster County officials and defense attorneys, acknowledge the existence of multi-session transcripts (over 350 combined pages) but do not index or quote this passage in digitized form. Newspaper, trial, and archival indices available online—including items at Lincoln Libraries and the Nebraska State Historical Society—lack specific reference to the Yankees, Los Angeles, or restaurant themes in direct quotations or transcript extracts.

This absence suggests that, while the quote may be reprinted in retrospectives or literary dramatizations, it is not verifiably documented in digitized or catalogued 1958 primary sources. To definitively confirm or rule out its existence, a physical review of the transcript collections listed by History Nebraska or onsite microfilm holdings of Lincoln-area newspapers from the trial period would be required.

McMurtry didn’t include footnotes.

A search of Google books reveals James M. Reinhardt included a phrase like this in two books that included Starkweather, one is The Murderous Trail of Charles Starkweather, the other is The Psychology of Strange Killers

Used copies of The Psychology of Strange Killers are dear in price but I might have to get one to review for this important website. Perhaps the original source lies in these boxes at the University of Nebraska. Here we abandon the trail, unless any readers want to cut for sign.

Mary Hart

Posted: October 28, 2025 Filed under: baseball Leave a comment

(source, an awkward still from a video)

Reading about Dodger superfan Mary Hart, who can often be seen sitting behind home plate on the TV broadcast.

Mary Harum was born in Madison, South Dakota. She was raised in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and Denmark. She speaks English, Danish and Swedish fluently.

She has an apartment (Wikipedia reports) in Sierra Towers, a prominent West Hollywood building:

The building is known for being more than 15 stories taller than any other building within a 2-mile (3.2 km) radius. Due to Sierra Towers’ unique positioning at the base of a hill (the same hill from which Beverly Hills gets its name), the building is the highest residential tower in the greater Los Angeles Area relative to sea level. The building is said to get its plural name from scuttled original plans to build a second tower

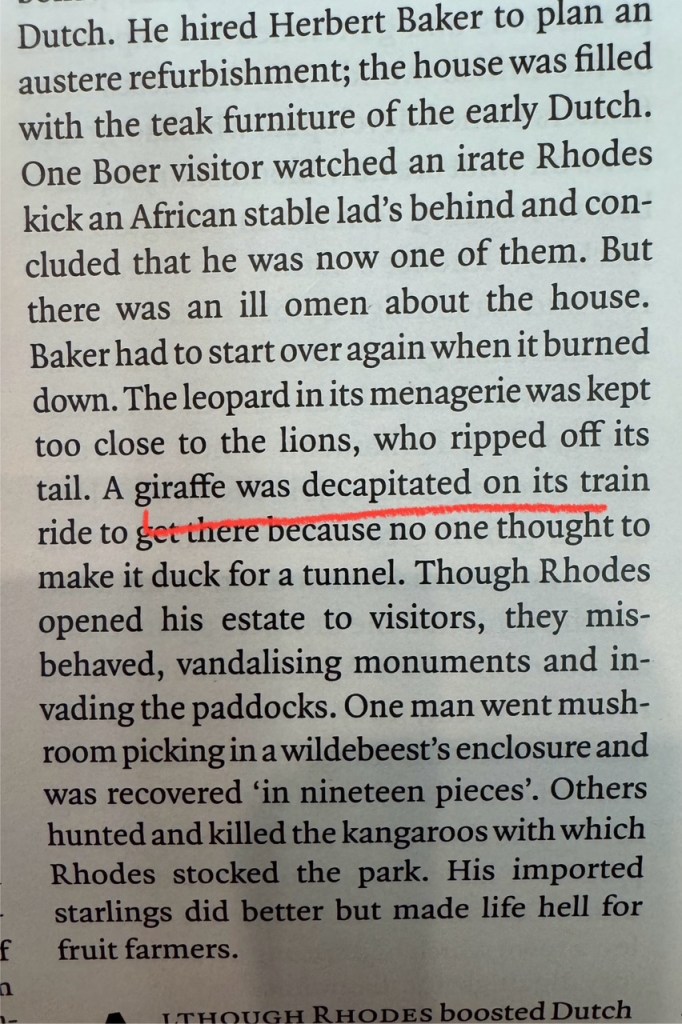

Cecil Rhodes

Posted: October 28, 2025 Filed under: Africa Leave a comment

from Michael Ledger-Lomas’s review of The Colonialist: The Vision of Cecil Rhodes by William Kelleher Storey in LRB.

The Rhodeses were farmers turned developers who had grazed cows on what are now Bloomsbury squares before building terraces in Islington and Hackney. Rhodes’s father attended Harrow and Cambridge before taking orders. His maternal grandfather was a provincial banker who had built canals in the Midlands and got into Parliament. When ill health caused young Cecil to join his brother Herbert in growing cotton in Natal, he went with two thousand pounds from his aunt, which cushioned the brothers against their amateurism. While African labourers hoed rows for them, they wandered into the interior, looking for gold and diamonds. Herbert could not stick at anything for long. In 1879 he died when a barrel of spirits exploded at his campfire and burned him to death. Cecil had by then settled at Kimberley, a town which had sprung up around the ‘dry diggings’ for diamonds.

Picks and shovels -> amalgamation and capital.

Rhodes and his first employer, Charles Rudd, found it easier to make money on side ventures, such as buying a steam-powered ice machine to sell refreshments to miners (Rhodes scooped the ice cream). But when colonial officials grudgingly decreed that diggers and miners could buy one another out and so concentrate holdings, Rhodes and Rudd founded a company to buy up claims in what had come to be known as the De Beers mine. The colony’s policy change reflected the diminishing viability of small-scale mining. Though the diamonds appeared inexhaustible, at deeper levels they were embedded in rock – the ‘blue ground’ – that required costly processing. Tottering over every claim was ‘reef’, friable rocks that often collapsed and buried the diamonds for months. Rhodes’s occasional trips to Britain reassured him that the demand for diamonds was buoyant enough to make it worthwhile to tackle these difficulties, but only if companies could supply capital and machinery, such as steam-powered pumps, at scale.

Personal life:

In the 1970s, the Tory historian Robert Blake dismissed speculation on his sexuality with the testy claim that he was simply one of those men who find getting married too much hassle. Rhodes would probably not have declared himself a homosexual, if he had known the word: he did not need to, living on the macho frontier. No one found it odd when he set up house at Kimberley with Neville Pickering and cradled him in his arms as he grew sick and died. Rhodes filled the void at his loss by hiring dashing young men as secretaries (shorthand not required), who borrowed his clothes and took his cheques but were cast adrift when they got engaged. No women worked at Groote Schuur, which was decorated with stone phalluses from the ruins of Great Zimbabwe (supposedly Phoenician relics that illustrated the ancient colonisation of Africa). He built up a coterie of unmarried thinkers and publicists, whose childlessness heightened their devotion to the Anglo-Saxon race.

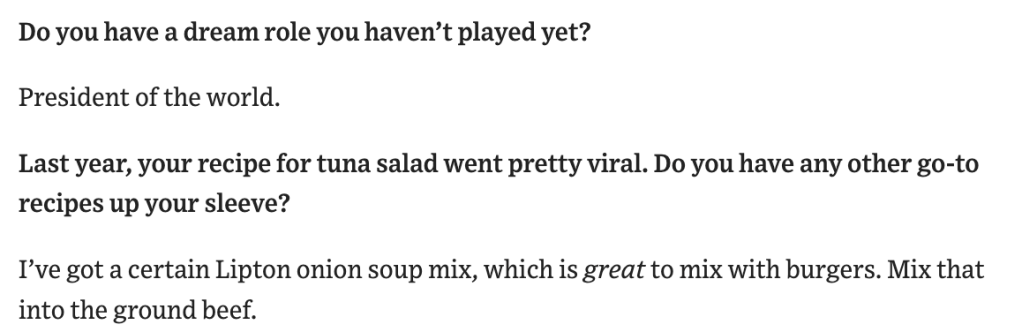

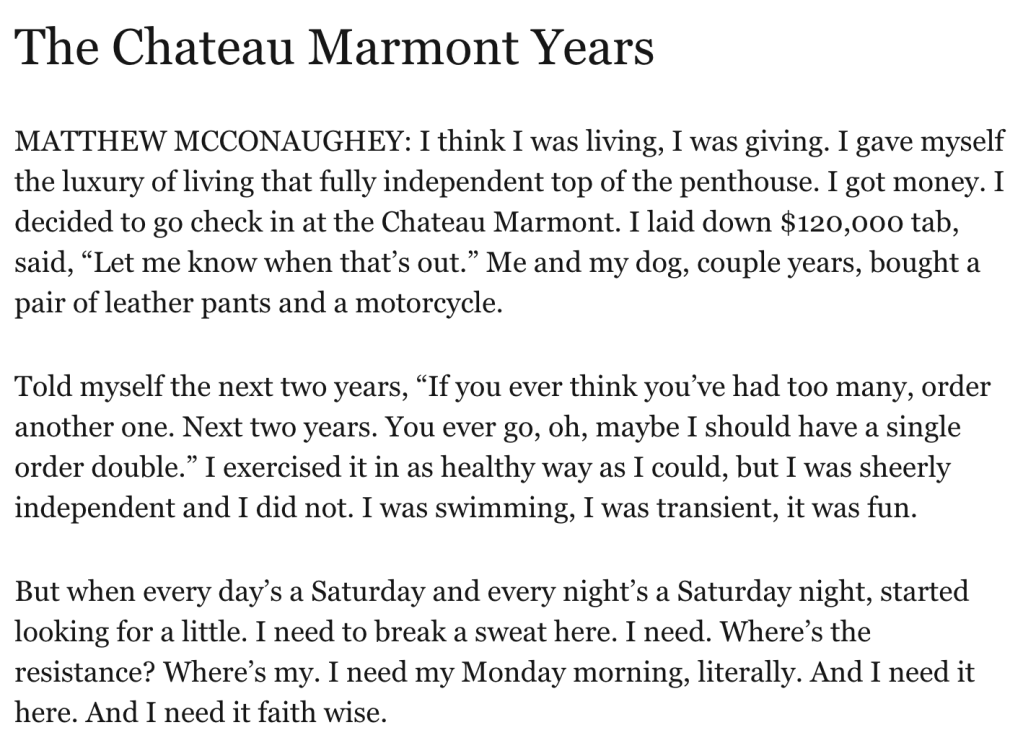

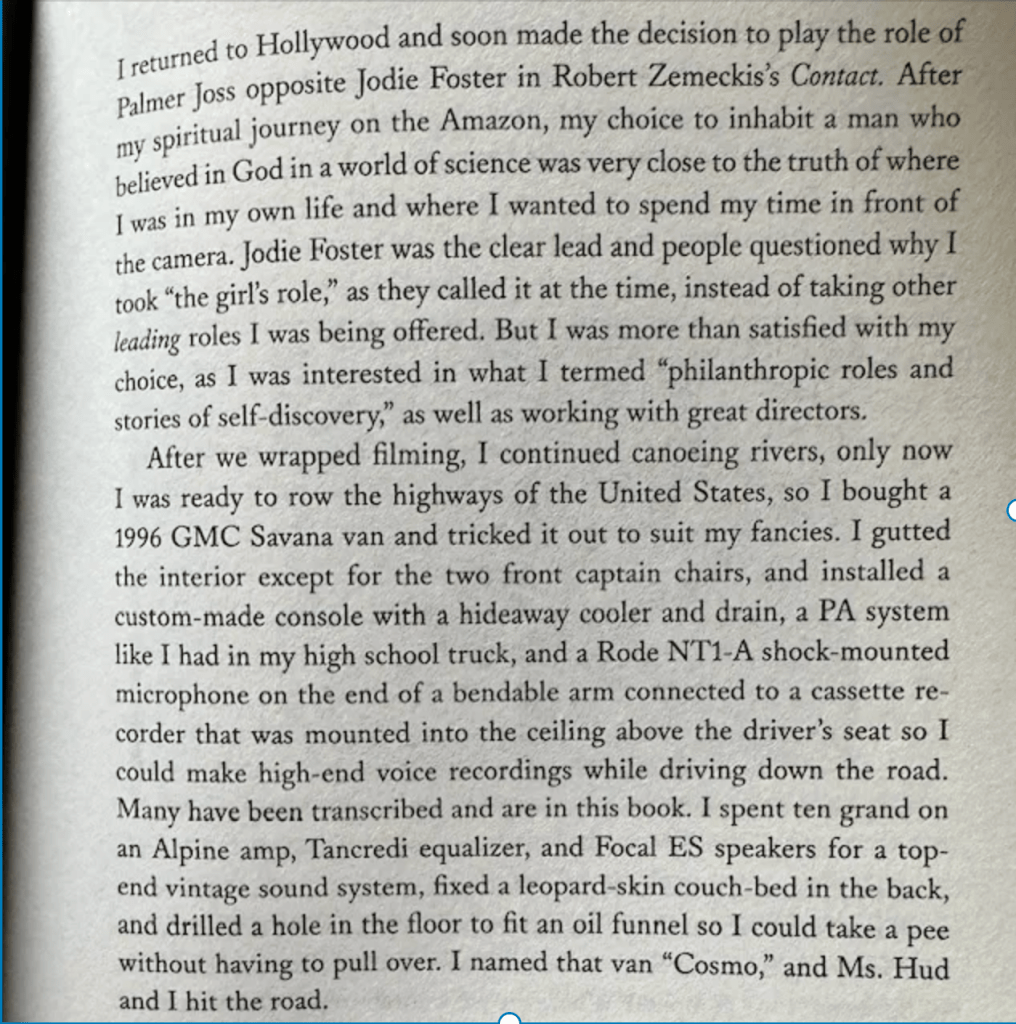

More McConaughey: Want To Be Here

Posted: October 28, 2025 Filed under: advice, Hollywood Leave a comment

in WSJ.

in Singju Post

I always repeat this, but one of the coolest and simplest things I heard early on. I was onThe Jay Leno Show, my first talk show. He comes by the green room. He goes, “You nervous?” I go, “Yeah, a little bit.” He goes, “Look, I got simple advice, how to make this work.” I go what? He goes, “Just want to be here.” It’s always stuck with me: You just want to be there. All of a sudden the clock goes faster. You look back, you enjoy what you did more.

in Paper Magazine.

His Dallas Buyers Club diet:

That’s in Greenlights.

A striking aspect of Greenlights is how few of the stories take place on movie sets. For example, in this one paragraph he blows past the making of six different movies.

The actual making of movies may not be that interesting.

Greenlights is best received as an audiobook, as that’s how McConaughey composed it, talking into a microphone while driving:

Movieland by Jerome Charyn

Posted: October 25, 2025 Filed under: Hollywood Leave a comment

I remember something Charles Laughton told Tyrone Power once upon a time. Be careful. If Power, the movie star, wanted to act on stage, he would have to shed a particular demon. He might be an actor reading his lines, but he would “also be the monster, made up of all the characters [Power had played on the screen.” And Power would have to dispose of that monster by breathing and looking like a man. Perhaps. But the monster would still be behind every move. That mingling of time, roles half-remembered

About Louis B. Mayer and Fritz Lang’s M:

Where’s the love interest? Louis B. Mayer would have asked. What about the happy ending? Hollywood would hire Fritz Lang and Peter Lorre, the director and the star of M, a movie about a child murderer that turns in upon itself, like an amazing corkscrew, as Lorre, with an “M” marked on his back, tries to explain his own demons to the underworld of Berlin, who’ve captured Lorre and sentenced him to death, because his very existence has threatened their own profitable relationship with the police. M is a kind of Brechtian opera without song.

But Lorre’s cry to the underworld screams in our ear, forces us to examine who the hell we are. It’s not designed to comfort us in the dark. Lorre’s chubby, childlike face seems to make monsters of us all. We partake of his death. We convict him, as we convict ourselves.

Mayer never read scripts. But the idea of such a movie would have enraged him. He’d have demanded that a pair of lovers be thrown into the pot. Some police inspector, played by Richard Dix (borrowed from RKO for such a minor vehicle), and a queen of the underworld who reforms herself and marries Dix, while the murderer is shoved into the background. But whatever the limits of MGM, all its sugared life on screen, only Mayer’s Hollywood could have conceived Casablanca and Gone With the Wind.

Its message was that no one in America need be exempt from love. The newsboy could marry the millionairess if only he was industrious enough, and looked a little like Gable. Nothing got in the way of romance. In The Last Tycoon, F. Scott Fitzgerald has his film producer Monroe Stahr explain the basic melody of any motion picture. “We’ve got an hour and twenty-five minutes on the screen-you show a woman being unfaithful to a man for one-third of that time and you’ve given the impression that she’s one-third whore.”

Thalberg:

MGM was only a little giant, not to be compared with Paramount, which had De Mille and Gloria Swanson and Clara Bow, or United Artists, formed in 1919 by Chaplin, Mary and Doug, and D. W. Griffith, or that enormous acreage Irving left behind with Uncle Carl at Universal City. It was Hollywood, after all, and film companies could come and go, like those pirates who’d arrived in California, running from Edison’s people. Mayer wasn’t as even-tempered as Uncle Carl, and no one thought the Boy Wonder would survive very long with the junkman. But Irving had matured in movie-land. He was twenty-four. He’d given up woolen underwear and become a fixer. He could patch up any film. He was the producer-magician who could sense a structural flaw and locate the melody of a given scene. The Thalberg legend began to grow. “Of this slim, slight, nervous man it was said he lived in a motion picture theater all his waking hours and knew instincitively whether the shadows on screen would please the public.”

On Fitzgergald’s Love of the Last Tycoon:

Stahr was a popularist of the imagination, a tender of dream-scapes. He could assume only one condition, that he “take people’s own favorite folklore and dress it up and give it back to them. Anything beyond that is sugar.”

But Fitzgerald himself understood the power of that dream-scape, the magic behind the hollow walls. “Under the moon the back lot was thirty acres of fairyland-not because the locations really looked like African jungles and French châteaux and schooners at anchor and Broadway by night, but because they looked like the torn picture books of childhood, like fragments of stories dancing in an open fire.”

The fire of Plato’s cave.

On Raymond Chandler:

He was a very formal man, bound by the strict codes of Dulwich College. Chandler wouldn’t walk into the street without a jacket and a tie, but he was also a Bedouin in his ways, often moving once or twice a year. He had over seventy different addresses in Southern California. And he was an alcoholic. He lost his job in the middle of the Depression because of the drinking he did. And the failed poet started writing fiction for the pulp magazines. “I had to learn American just like a foreign language.”

He saw himself as “a man without a country,” neither English nor American, but some kind of cultural half-breed caught in the crazy quilt of Southern California, where men and women had to reinvent their lives. And Chandler, a good Dulwich boy who longed for tradition, had come to a place without a past, where whole peoples had to define themselves against the deserts, mountains, valleys, seas, and citrus groves.

Chandler was one more anonymous soul who’d become “a plots. y writer with a touch of magic and a bad feeling about His apprenticeship wasn’t easy. He didn’t publish his first novel until he was fifty-one. And even after Philip Marlowe was world-famous, Chandler grumbled about his own status in the United States. English intellectuals idolized him, adored his work, and Chandler “tried to explain to them that I was just a He was a very formal man, bound by the strict codes of Dul-wich College. Chandler wouldn’t walk into the street without a jacket and a tie, but he was also a Bedouin in his ways, often moving once or twice a year. He had over seventy different addresses in Southern California. And he was an alcoholic. He lost his job in the middle of the Depression because of the drinking he did. And the failed poet started writing fiction for the pulp magazines. “I had to learn American just like a foreign language.”

He saw himself as “a man without a country,” neither English nor American, but some kind of cultural half-breed caught in the crazy quilt of Southern California, where men and women had to reinvent their lives. And Chandler, a good Dulwich boy who longed for tradition, had come to a place without a past, where whole peoples had to define themselves against the deserts, mountains, valleys, seas, and citrus groves.

Chandler was one more anonymous soul who’d become “a plots. y writer with a touch of magic and a bad feeling about His apprenticeship wasn’t easy. He didn’t publish his first novel until he was fifty-one. And even after Philip Marlowe was world-famous, Chandler grumbled about his own status in the United States.

…

He understood that film was “not al transplanted literary or dramatic art … it is much closer to music, in the sense that its finest effects can be independent of precise meaning, that its transitions can be more eloquent than its high-lit scenes, and that its dissolves and camera movements, which cannot be censored, are often far more emotionally effective than its plots, which can.”

Finish drafts

Posted: October 24, 2025 Filed under: advice, writing, writing advice from other people 1 Comment

Woody Allen: NOT in fashion.

I’m interested only in his productivity. Whatever else you say about him, my guy made a lot of movies. How?:

appears in an interview from 2015 with Richard Stayton in Written By magazine.

(For the love of Buddha if you are easily triggered don’t look at the WGA’s list of 101 funniest screenplays)

Henry Adams on Harvard in 1800

Posted: October 23, 2025 Filed under: New England Leave a comment

from Garry Wills, Henry Adams and the Making of America, a must for Adams-heads.

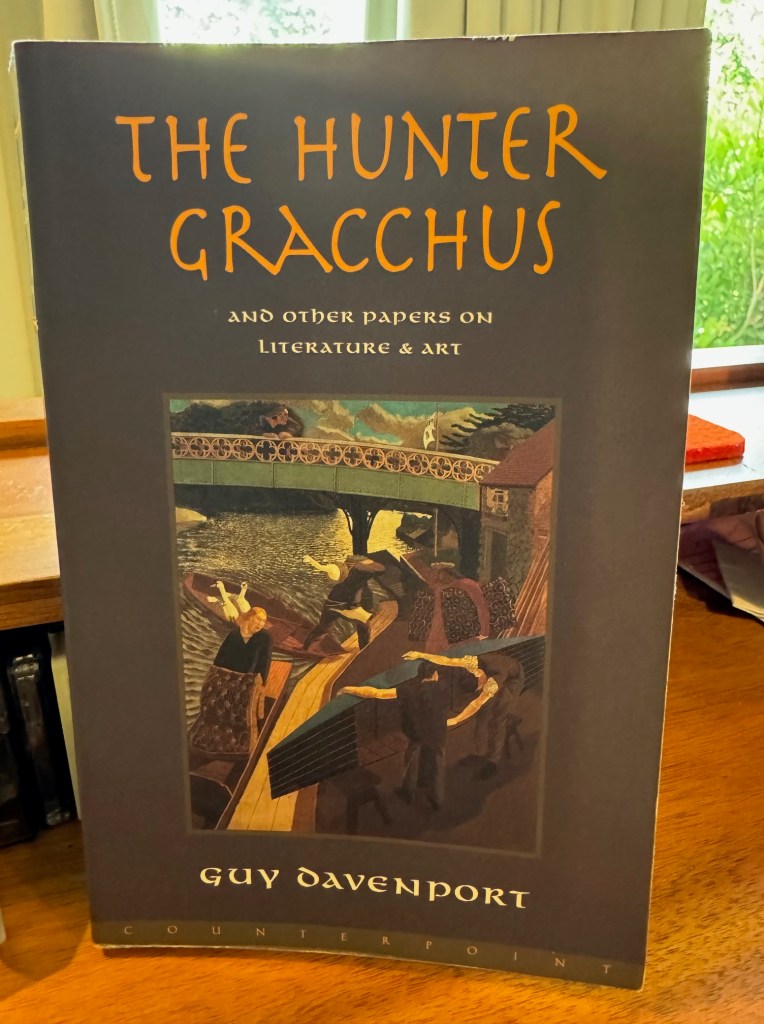

The Hunter Gracchus by Guy Davenport

Posted: October 20, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, New England Leave a commentRevisited this one after seeing some footage from The Testament of Ann Lee.

Hoedown

Posted: October 18, 2025 Filed under: music Leave a commentIn October 1937, in the town of Saylersville in Magoffin County, Kentucky, Alan Lomax recorded William Hamilton Stepp playing a fiddle tune called “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” or as he identifies it in the recording, “the Bonaparte.”

Some years later, Aaron Copland found a transcript of the recording in a book:

Composer Aaron Copland, who was commissioned by choreographer Agnes De Mille to score the ballet in 1942, probably did not hear the original field recording before adapting it. Instead, he likely learned the tune from the book Our Singing Country (1941), which presented transcriptions of John and Alan Lomax’s field recordings prepared by the composer and musicologist Ruth Crawford Seeger. According to Jabbour, “when Aaron Copland was looking for a suitable musical theme for the ‘Hoedown’ section of his ballet Rodeo (first produced in 1942), his eye was caught by the version in the Lomax book, and he adopted it almost [note] for note as the principal theme.”

(source)

In 1972, Emerson Lake & Palmer recorded an electronic version:

Some years after that, in 1993, I heard the tune on TV in a “Beef: It’s What’s For Dinner” commercial. They play “Hoedown” from Copland’s Rodeo all the time on KUSC.

I note all this because I’m interested in transmissions from the past to the present. Fiddle tune -> recording -> transcription -> orchestral score -> recording -> TV commercial is an cool lineage.

Columbus Day

Posted: October 13, 2025 Filed under: America Leave a comment

Many people are unaware that Columbus made not just one voyage but four; others are surprised to learn that he was brought back in chains after the third voyage. Even fewer know that his ultimate goal, the purpose behind the enterprise, was Jerusalem! The 26 December 1492 entry in his journal of the first voyage, hereafter referred to as the Diario, 3 written in the Caribbean, leaves little doubt. He says he wanted to find enough gold and the almost equally valuable spices “in such quantity that the sovereigns… will undertake and prepare to go conquer the Holy Sepulchre; for thus I urged Your Highnesses to spend all the profits of this my enterprise on the conquest of Jerusalem” (Diario 1492[1988: 291, my emphasis]).4 This statement implies that it was not the first time Columbus had mentioned the motivation for his undertaking, nor was it to be the last.5 Columbus wanted to launch a new Crusade to take back the Holy Land from the infidels (the Muslims). This desire was not merely to reclaim the land of the Bible and the place where Jesus had walked; it was part of the much larger and widespread, apocalyptic scenario in which Columbus and many of his contemporaries believed.

That from an article by Carol Delaney of Stanford, “Columbus’s Ultimate Goal: Jerusalem.”

Columbus knew from Marco Polo that there was a Great Khan somewhere to the west/east, and that this Khan had requested emissaries from the Pope. So possibly the Khan could be an ally against the Muslims.

In case he should encounter the Great Khan or other emperors, kings, or princes, it was deemed appropriate for Columbus to carry letters of greeting from the sovereigns (with space left blank for the addressee) and to take along as an interpreter Luis de Torres, a converso who knew Hebrew, Chaldean, and some Arabic. It was highly unlikely that anyone in Spain knew Mongolian or Chinese, but since ‘it was supposed that Arabic was the mother of all languages’ (Morison 1942, vol. I: 187), it was assumed that Arabic would suffice.”

Columbus and the other conquistador types commissioned by the King and Queen of Spain must be seen in the conquest of the Reconquista, the 700 year effort to drive Islam from Iberia. Cortes, for example, was a religious fanatic, who used the Spanish word “moscas” or mosques to describe the temples he found in the land of the Aztecs.

(Ridley Scott gets at some of this in 1492: Year of Discovery. My mom at least wanted to walk out of this movie once it gets to the torturing. Sigourney Weaver plays Queen Isabella.)

Delaney expands from Columbus’s religiosity to some bigtime thoughts on how we, today, may not be able to grasp what “religion” meant to someone like Columbus:

The modern understanding of religion did not fully emerge until the late nineteenth century when scholars began to attach “-ism” to make substantives out of adjectives—Buddhism rather than Buddhist, Hinduism rather than Hindu—thus making a ‘religion’ by separating out the spiritual elements from a whole way of life or culture that included ethnicity, language, food, dress, and other practices (see Smith 1962; Rawlings 2002). In reality, however, science, technology, and religion can be and are easily and seamlessly combined. For example, I found Turkish villagers, while mostly illiterate and uneducated, could discuss, understand, make, use, and fix a variety of modern machines and equipment including automobiles, telephones, and television sets; they could talk about international and national politics with more sophistication than most Americans, and they understood the economic networks with which their lives were entangled. They would appear to have a thoroughly modern consciousness. But staying long, getting to know them, and “pushing the envelope,” revealed to me how, at a much deeper level, they lived within a completely Islamic cosmology or worldview. That worldview encompassed their lives, it was the context within which they lived, and it provided answers to the perennial questions: who are we, why are we here, where are we going? It also affected the way they dressed, the food they ate, their practices of personal hygiene, the way they moved, and their spatial and temporal orientations (see Delaney 1991). It was inseparable from the rest of their lives, not something they practiced only on Fridays, the Muslim holy day, or by keeping the fast of Ramadan. Though they evinced varying degrees of devoutness, secularism was not an option. They believed their views were self-evident to any thinking person and they could not understand why I could not accept Islam and, in their terms, submit and become Muslim. Islam, to them, is not one religion among others; it is “Religion.” It is the one true religion given in the beginning to Abraham, and Muhammad was merely a prophet recalling people to that original faith. They had heard of Christianity, of course, and questioned me about it. But to them it was not a separate, equally valid religion, but rather a distortion of the one true word, the one true faith.

Just so did Columbus and his contemporaries view the sectas of the Jews and Muslims. His statement about freeing the Indians from error shows that religion was not a matter of choice but of right or wrong—there was only one right way. Indeed, they really had no conception of alternatives. The Reformation had not yet begun, and Judaism and Islam were seen not as different religions but as erroneous, heretical sects

Like a good anthropologist she quotes Clifford Geertz:

The anthropological critique of this position has been insistent: “[T]he image of a constant human nature independent of time, place, and circumstance, of studies and professions, transient fashions and temporary opinions, may be an illusion, that what man is may be so entangled with where he is, who he is, and what he believes that it is inseparable from them” (Geertz 1973: 35). In other words, there is no backstage where we can go to find the generic human; humans are formed within specific cultures. This does not mean that cultures are totally closed or that there is no overlap; one can learn another culture—that is, indeed, what anthropologists do during fieldwork. But if we are to understand Columbus (or anyone else), we must attempt insofar as is possible to reconstruct the world in which he lived. While some historians writing about Columbus appear to do this, they still, in my reading, project a modern consciousness onto him, leaving the impression that the time and place are merely “transient fashions.”

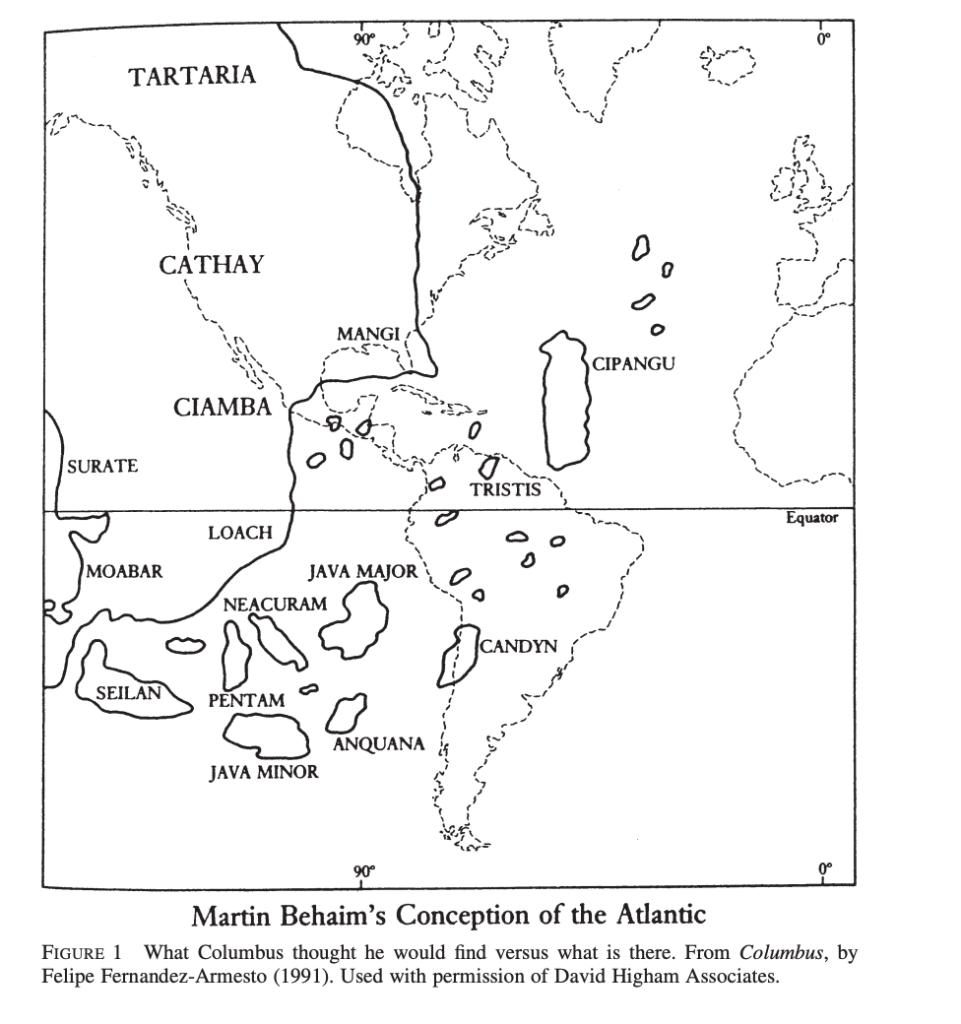

Delaney includes a great map, which I steal:

Since I was a kid the tone around Columbus has been a lot less “In fourteen hundred ninety two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue” and more he was a genocidal colonialist. But applying our concepts in moral judgment of these figures of the past seems not that far from Columbus applying his concepts to the native people he discovered. Then again, evolving our conceptions and adjusting our heroes as we go seems healthy, right?

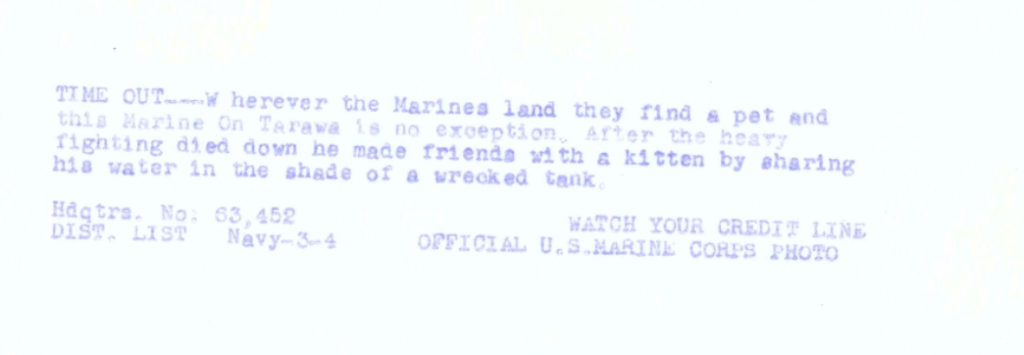

Photograph of a Marine Giving Water to a Kitten on Tarawa

Posted: October 11, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945 1 Comment

perusing the National Archives Record Group 38 as one does and found this.

Also:

This looks like a boring job

Posted: October 11, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

although who knows, maybe it was hypnotic. from Lewis Hine’s photographs for the WPA