Lincoln in New Orleans (featuring final answer on was Abraham Lincoln gay?)

Posted: January 18, 2025 Filed under: Mississippi, New Orleans, presidents Leave a comment

In the year 1828 nineteen year old Abraham Lincoln went on a flatboat trip with a local twenty one year old named Allen Gentry. He would be paid eight dollars a month plus steamboat fare home. They left from Spencer County, Indiana, down the Ohio to the Mississippi.

The great New Orleans geographer and historian Richard Campanella wrote a whole book, Lincoln In New Orleans, about Lincoln’s experience on this trip and another down in New Orleans. It’s a really illuminating work on Lincoln, the Mississippi River at that time, the floatboatman life, early New Orleans.

If you need step by step instructions on building a flatboat, they’re in Campanella’s book. (People back then worked so hard!)

Campanella tells us in vivid reconstruction from various sources what this trip must’ve been like:

the Mississippi River in its deltaic plain no longer collected water through tributaries but shed it, through distributaries such as bayous Manchac, Plaquemine, and Lafourche (“the fork”). This was Louisiana’s legendary

“sugar coast,” home to plantation after plantation after plantation, with their manor houses fronting the river and dependencies, slave cabins, and

“long lots” of sugar cane stretching toward the backswamp. The sugar coast claimed many of the nation’s wealthiest planters, and the region had one of the highest concentrations of slaves (if not the highest) in North America. To visitors arriving from upriver, Louisiana seemed more Afro-Caribbean than American, more French than English, more Catholic than Protestant, more tropical than temperate. It certainly grew more sugar cane than cotton (or corn or tobacco or anything else, probably combined).

To an upcountry newcomer, the region felt exotic; its society came across as foreign and unknowable. The sense of mystery bred anticipation for the urban culmination that lay ahead.

What Lincoln did in New Orleans is recorded only in a few stray remarks from the man himself and secondhand stories remembered afterwards by those he told them to, who then told them to William Herndon, biographer and law partner of Lincoln. (now they can be found in a volume called Herndon’s Informants). What was Lincoln like in New Orleans?

Observing the behavior of young men today, sauntering in the French Quarter while on leave from service, ship, school, or business, offers an idea of how flatboatmen acted upon the stage of street life in the circa-1828 city. We can imagine Gentry and Lincoln, twenty and nineteen years old respectively, donning new clothes and a shoulder bag, looking about, inquiring what the other wanted to do and secretly hoping it would align with his own wishes, then shrugging and ambling on in a mutually consensual direction. Lincoln would have attracted extra attention for his striking physiognomy, his bandaged head wound from the attack on the sugar coast, and his six-foot-four height, which towered ten inches over the typical American male of that era and even higher above the many New Orleanians of Mediterranean or Latin descent.

Quite the conspicuous bumpkins were they.

One cannot help pondering how teen-aged Lincoln might have behaved in New Orleans. Young single men like him (not to mention older married men) had given this city a notorious reputation throughout the Western world; condemnations of the city’s wickedness abound in nineteenth-century literature. A visitor in 1823 wrote,

New Orleans is of course exposed to greater varieties of human misery, vice, disease, and want, than any other American town. … Much has been said about [its] profligacy of manners, morals… debauchery, and low vice … [T]his place has more than once been called the modern Sodom.

Campanella considers what we know about Lincoln and women:

I consider the matter concluded that Abe was a gentle shyguy ladykiller.

I found this passage very real:

Campanella gives us the political context of the time:

There was much to editorialize about in the spring of 1828. A concurrence of events made politics particularly polemical that season. Just weeks earlier, Denis Prieur defeated Anathole Peychaud in the New Or-leans mayoral race, while ten council seats went before voters. They competed for attention with the U.S. presidential campaign— a mudslinging rematch of the bitterly controversial 1824 election, in which Westerner Andrew Jackson won a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote in a four-candidate, one-party field, but John Quincy Adams attained the presidency after Congress handed down the final selection. Subsequent years saw the emergence of a more manageable two-party system. In 1828, Jackson headed the Democratic Party ticket while Adams represented the National Republican Party (forerunner of the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party). Jackson’s heroic defeat of the British at New Orleans in 1815 had made him a national hero with much local support, but did not spare him vociferous enemies. The year 1828 also saw the state’s first election in which presidential electors were selected by voters-white males, that is—rather than by the legislature, thus ratcheting up public interest in the contest. 238 Every day in the spring of 1828 the local press featured obsequious encomiums, sarcastic diatribes, vicious rumors, or scandalous allegations spanning multiple columns. The most infamous-the “coffin hand bills,” which accused Andrew Jackson of murdering several militiamen executed under his command during the war—-circulated throughout the city within days of Lincoln’s visit. 23% New Orleans in the red-hot political year of 1828 might well have given Abraham Lincoln his first massive daily dosage of passionate political opinion, via newspapers, broadsides, bills, orations, and overheard conversations.

Before they got to New Orleans, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked by a group of seven Negroes, possibly runaway slaves? Little is known for sure about the incident, except that they messed with the wrong railsplitter. Lincoln was famously strong and a good fighter:

In a remarkable bit of historical detective work, Campanella concludes that a woman sometimes called “Bushan” may have been Dufresne, and puts together this incredible map:

Really impressed with Campanella’s work, I also have his book Bienville’s Dilemma, and add him to my esteemed Guides to New Orleans. Campanella goes into some detail about how and in what forms Lincoln would’ve encountered slavery on this trip. Any dramatic statement about it he made during the trip though seems historically questionable. When Lincoln talked about this trip in political speeches, he used it as an example of how he’d once been a working man. For example, 1860 in New Haven:

Free society is such that a poor man knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition-when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him!’

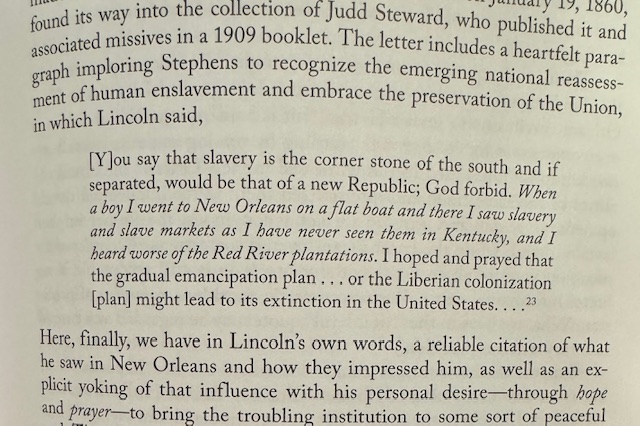

Campanella does cite a letter Lincoln wrote in 1860 where he did speak on what he saw of slavery:

Making a flatboat trip was a rite of passage for a young buck of the Midwest at that time. Whether it brought Lincoln to full maturity is discussed in a poignant and comic anecdote:

An awkward incident one year after the New Orleans trip yanked the maturing but not yet fully mature Abraham back into the petty world of past grievances. How he dealt with it reflected his growing sophistication as well as his lingering adolescence. Two Grigsby brothers— kin of Aaron, the former brother-in-law whom Abraham resented for not having done enough to aid his ailing sister Sarah Lincoln-married their fiancées on the same day and celebrated with a joint “infare.” The Grigsbys pointedly did not invite Lincoln. In a mischievous mood, Abraham exacted revenge by penning a ribald satire entitled “The Chronicles of Reuben,” in which the two grooms accidentally end up in bed together rather than with their respective brides. Other locals suffered their own indignities within the stinging verses of Abraham’s poem, nearly resulting in fisticuffs. The incident botses tected and exacerbated Lincoln’s growing rift with all things related to Spencer County.

An article version of Campanella’s book is available free.

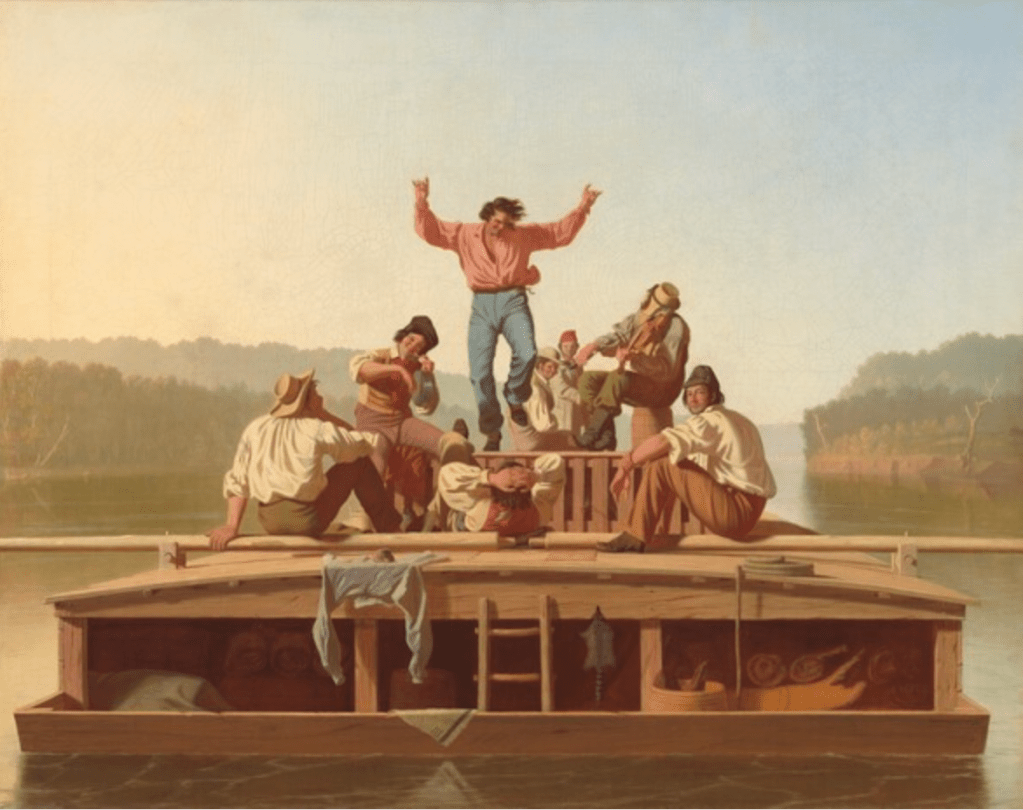

That painting is of course Jolly Flatboatmen, which we discussed back in 2012.

Stinkards and Suns of Mississippi

Posted: October 19, 2024 Filed under: Mississippi Leave a comment

This is a description of the Natchez people, found in:

Southern Union State Junior College’s loss is my gain.

Optimal outcome: to be a hot Stinkard?

The source for this information is the Histoire de la Louisiane set down by Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, who had an adventurous life, including time spent among the Natchez around 1720-1728:

A dance:

Du Pratz (or Le Page’s) book was translated into English, and a copy was loaned by Benjamin Barton:

to Meriwether Lewis to take on his expedition with his bro Clark.

The Natchez people had a tough history. At the Michigan State Vincent Voice Library, there are some audio samples recorded in the 1930s of Watt Sam, one of the last native speakers of Natchez (or Natche) telling stories in the language. Regrettably these don’t seem to be available online. If anyone in the Lansing area can check it out for us, we’d be appreciative. It’s not urgent.

An intriguing aspect of the Natchez language was “cannibal speech”:

Traditionally the Natchez had certain stories that could only be told during the winter time, and many of these stories revolved around the theme of cannibalism. Protagonists in such stories would encounter cannibals, trick cannibals, marry the daughters of cannibals, kill cannibals, and be eaten by cannibals. In these stories Natchez storytellers would employ a special speech register when impersonating the cannibal characters. This register was distinct from ordinary Natchez by substituting several morphemes and words for others.

Sometimes I wonder if the linguists make too much of this stuff, when it was really just the Natchez doing spooky voices in their scary story.

History: rhyming or nah?

Posted: June 5, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, Mississippi 2 CommentsThis is from the annual letter of Kanbrick, an investment company run by Warren Buffett protege Tracy Britt Cool:

You’ve maybe heard this Mark Twain quote before. Here’s what bothers me: there’s no evidence Twain ever said this. It’s not anywhere in his writings (easily searchable). Maybe he said it to some person who wrote it down? Well, Quote Investigator can’t find that quote anywhere in print until 1970.

Twain did write this:

NOTE. November, 1903. When I became convinced that the “Jumping Frog” was a Greek story two or three thousand years old, I was sincerely happy, for apparently here was a most striking and satisfactory justification of a favorite theory of mine—to wit, that no occurrence is sole and solitary, but is merely a repetition of a thing which has happened before, and perhaps often.

but that’s not quite the same thing, is it?

Now, you might say, who cares? But, like, Kanbrick’s job is researching, and curiosity, and getting facts right. If Twain made this interesting statement, wouldn’t it be worth finding out to whom he said it? or where he wrote it? and in what context? Even Mark Twain didn’t go around saying aphorisms. He said stuff in a setting. If Kanbrick had gone looking for the context, they wouldn’t have found it. So, they weren’t curious?

Look, let’s let Kanbrick off the hook here, they’re an investment firm. But here’s Ken Burns in a graduation speech at Brandeis University:

We continually superimpose that complex and contradictory human nature over the seemingly random chaos of events, all of our inherent strengths and weaknesses, our greed and generosity, our puritanism and our prurience, our virtue, and our venality parade before our eyes, generation after generation after generation. This often gives us the impression that history repeats itself. It does not. “No event has ever happened twice, it just rhymes,” Mark Twain is supposed to have said. I have spent all of my professional life on the lookout for those rhymes, drawn inexorably to that power of history. I am interested in listening to the many varied voices of a true, honest, complicated past that is unafraid of controversy and tragedy, but equally drawn to those stories and moments that suggest an abiding faith in the human spirit, and particularly the unique role this remarkable and sometimes also dysfunctional republic seems to play in the positive progress of mankind.

Now, Ken Burns at least gives the qualifier “supposed to have said,” but… Ken Burns made a 212 minute long documentary about Mark Twain! He must’ve steeped himself in Mark Twain! Did he not want to check out the context? I would guess that he just found it too good a quote to lose, and Mark Twain too good a source to put it too.

Here’s the IMF slapping down the quote without even a “supposed to have said.”

People chalk up quotes to Mark Twain and Churchill and Einstein all the time. That’s sorta just human nature to give these witty remarks to folk heroes famous for wisdom and smarts. The part that bothers is me is that no one, even in annual letters to investors and graduation speeches, was curious enough to be like “what was the context here for this quote I like? What was Twain saying? Where did he say it?”

It’s never been easier to find something like that out, it can be done in a few minutes. In the old days you had to walk to Cambridge and find the bookseller Bartlett, who knew every quote. Eventually Bartlett got tired of the inquiries and published a book, which is now an app.

Perhaps you’re thinking, Steve, who cares? These folks wanted to sauce their speech a little bit, does it matter? Maybe not. But as Mark Twain said, “what’s a personal website for if not working out life’s little irritants?”

Related: did Fitzgerald mean that thing about “no second acts in American lives“? Or did he conclude the exact opposite? (I’ve sometimes wondered if F. meant no second acts in the sense of like a three act Broadway play, like: American lives go right from the first act to the third act.)

William Faulkner’s introduction to Sanctuary

Posted: December 31, 2023 Filed under: memphis, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentThe best character William Faulkner ever created was himself, William Faulkner. The flying injury, Rowan Oak, the photographs, the guest roles, the interviews, scraps of footage, the Nobel Prize speech. Perfect.

In 1929 William Faulkner, then age 31, wrote Sanctuary, which has one of the trashiest loglines ever: Ole Miss coed Temple Drake ends up the sex slave of a gangster named Popeye. Here at Helytimes we won’t go into detail of what exactly Popeye does, we leave that to lesser publications like The Washington Post:

what interested him chiefly about this horrific event was “how all this evil flowed off her like water off a duck’s back.” In his haste to make a best seller, he crammed in all he had seen and heard about whorehouses, rapes and kidnappings.

This was a ripped from the headlines story based on a true crime case. As a Mississippi crime book complete with courtroom scenes, it’s kind of a proto-Grisham.

Sanctuary was published by Jonathan Cape in 1931. Then in 1932 the Modern Library put out a new edition with a new introduction by Faulkner. Scholars since have apparently debunked everything Faulkner claimed in this introduction as fabulations and lies but so what? In a way that makes it even better. A work of autofiction.

We couldn’t find this introduction online so we got a used copy and scanned it in, it’s out of copyright (we believe?).

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN THREE YEARS AGO. To me it is a cheap idea, because it was deliberately conceived to make money. I had been writing books for about five years, which got published and not bought. But that was all right. I was young then and hard-bellied. I had never lived among nor known people who wrote novels and stories and I suppose I did not know that people got money for them. I was not very much annoyed when publishers refused the mss. now and then. Because I was hard-gutted then. I could do a lot of things that could earn what little money I needed, thanks to my father’s un- failing kindness which supplied me with bread at need despite the outrage to his principles at having been of a bum progenitive.

Then I began to get a little soft. I could still paint houses and do carpenter work, but I got soft. I began to think about making money by writing. I began to be concerned when magazine editors turned down short stories, concerned enough to tell them that they would buy these stories later anyway, and hence why not now. Meanwhile, with one novel completed and consistently refused for two years, I had just written my guts into The Sound and the Fury though I was not aware until the book was pub- lished that I had done so, because I had done it for pleasure. I believed then that I would never be published again. I had stopped thinking of myself in publishing terms.

But when the third mss., Sartoris, was taken by a publisher and (he having refused The Sound and the Fury) it was taken by still another publisher, who warned me at the time that it would not sell, I began to think of myself again as a printed object. I began to think of books in terms of possible money. I decided I might just as well make some of it myself. I took a little time out, and speculated what a person in Mississippi would believe to be current trends, chose what I thought was the right answer and invented the most horrific tale I could imagine and wrote it in about three weeks and sent it to Smith, who had done The Sound and the Fury and who wrote me immediately. ”Good God, I can’t publish this. We’d both be in jail.” So I told Faulkner, “You’re damned. You’ll have to work now and then for the rest of your life.” That was in the summer of 1929. I got a job in the power plant, on the night shift, from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M., as a coal passer. I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheel- barrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler. About 11 o’clock the people wuuld be going to bed, and so it did not take so much steam. Then we could rest, the fireman and I. He would sit in a chair and doze. I had invented a table out of a wheel- barrow in the coal bunker, just beyond a wall from where a dynamo ran. It made a deep, constant humming noise. There was no more work to do until about 4 A.M., when we would have to clean the fires and get up steam again. On these nights, between 12 and 4, I wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks, without changing a word. I sent it to Smith and wrote him that by it I would stand or fall.

I think I had forgotten about Sanctuary, just as you might forget about anything made for an immediate purpose, which did not come off. As I Lay Dying was published and I didn’t remember the mss. of Sanctuary until Smith sent me the galieys. Then I saw that it was so terrible that there were but two things to do: tear it up or rewrite it. I thought again, “It might sell; maybe 10,000 of them will buy it.” So I tore the galleys down and rewrote the book. It had been already set up once, so I had to pay for the

privilege of rewriting it, trying to make out of it something which would not shame The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying too much and I made a fair job and I hope you will buy it and tell your friends and I hope they will buy it too.WILLIAM FAULKNER. New York, 1932.

Happy New Year to all 6,722 of our loyal readers, all over the globe.

Thad Cochran

Posted: December 17, 2023 Filed under: America Since 1945, Kennedy-Nixon, Mississippi, New England Leave a comment

Poking around the Edward Kennedy oral history project at The Miller Center I find this interview with former Mississippi senator Thad Cochran.

Cochran was a young Naval officer in Newport when he happened to get an invitation to the Kennedy compound from an Ole Miss coed friend who was working as cook there:

Heininger

What were your impressions of [Ted Kennedy] that very first time you met him in Hyannis Port?

Cochran

Very casual, easy to be with, approachable, good sense of humor, big appetite. He liked chocolate-chip cookies, I know that. He stood there and ate a whole fistful of chocolate-chip cookies, which my friend would make on request. She was apparently good at that.

As a young naval officer here’s what Cochran thought of the buildup to Vietnam:

But then the Vietnam thing came along, and it started getting worse and worse. I didn’t get called back in the Navy to serve in Vietnam, but I was teaching one summer in Newport when the Gulf of Tonkin incident occurred. Just trying to figure that one out and reading about what had happened and looking at a couple of television things of the bombing of the port at—where was it, Haiphong, something like that? I thought, I cannot believe this. What the heck is President Johnson thinking? What is he doing? How are we going to back away from that now, responding to this attack against a merchant ship, as I recall?

Anyway, I began worrying about it. I think, in one of my classes, I even asked the students, the officer candidates about to be officers in the U.S. Navy, would they like to go over to Vietnam and fight over this? Would they like to escalate this another notch? Is there something in our national interest? Of course they were scared to death of it. They didn’t want to say anything, but I think I expressed my view kind of gratuitously, and then later I worried that I was going to get reported for being a belligerent, anti-American Naval officer. I really became angry and frustrated and upset with the way this thing was going, and it just got worse, as everybody knows.

How did he end up in elected office?:

So then I went back to practicing law and just working and enjoying it. I forgot about politics, and then our Congressman unexpectedly announced that he was not going to seek re-election. His wife had some malady, some illness, and the truth was, he was just tired of being up here and wanted to come home. It took everybody by surprise. I’m minding my own business again one day at the house and the phone rings, and it’s the local Young Republican county chairman, Mike Allred, who called and said,

You know, you may laugh but I’m going to ask you a serious question. This is serious. Have you thought about running for Congress to take Charlie Griffin’s place?And I said,Well,and I laughed because I said,You know, I have thought about it. I was surprised to hear that he wasn’t going to run, but I’ve thought about it, and I’ve decided that I’m not interested in running. I’ve got too much family obligation, financial opportunities, the law firm,etc.I think Congressmen were making about $35,000 a year or something like that. There was a rumor it might go up to $40,000. I thought, Well, I have a wife and two young children, and there’s no way in the world I can manage all that, and in Washington, traveling back and forth, etc. But it would be interesting. It’s going to be wide open. It was an interesting political situation. Then he said,

Well, let me ask you this: have you thought about running as a Republican?I laughed again and I said,No, I surely haven’t thought about that.I was just thinking about the context of running as a Democrat, and so I was still thinking of myself as a Democrat in ’72.He said,

Would you meet with the state finance chairman? We’ve been talking about who would be a good candidate for us to get behind and push, and we want to talk to you about it. We really think there’s an opportunity here for you and for our partyand all this. I said,Well, Mike, I’ll be glad to meet and talk to you all, but look, don’t be encouraged that I’m going to do it. But I’m happy to listen to whatever you say. I’d like to know what you all are doing, as a matter of curiosity, how you got off under this and who your prospects are and that kind of thing. I’d like to know that.So I met with them, and they started talking about the fact that they would clear the field. There would not be a chance for anybody to win the nomination if I said I would run. I thought, Golly, you all are really serious and think a lot of your own power. I started thinking about it some more, and I asked my wife what she would think about being married to a United States Congressman, and she said,

I don’t know, which one?[laughs] And that is a true story. I said,Hello. Me.Anyway, a lot of people had that reaction:

What? Are you seriously thinking about this?But everybody that I asked—I started just asking family and close friends, law partners; I just bounced it off of them—I said,What’s your reaction that the Republicans are going to talk to me about running for Congress?I was just amazed at how excited most people got over the idea that I might run for Congress and run as a Republican. That’s unique, and they wouldn’t have thought it because they knew I was not a typical Republican. The whole thing worked out, and I did run, and I did win.

That was ’72. Interesting dynamic in Mississippi that year:

Knott

Were you helped by the fact that [George] McGovern was running as the Democratic nominee that year?Cochran

Yes, indeed. There was no doubt about it. I was also helped by the fact that some of the African-American activists in the district were out to prove to the Democrats that they couldn’t win elections without their support. Charles Evers was one of the most outspoken leaders and had that view. He was the mayor of Fayette, Mississippi, and that was in my Congressional district. He recruited a young minister from Vicksburg, which was the hometown of the Democratic nominee, to run as an Independent, and he ended up getting about 10,000 votes, just enough to deny the Democrat a majority. He had 46,000 or something like that, and I ended up with 48,000 or whatever. I’ve forgotten exactly what the numbers were. The Independent got the rest.

So the whole point was, I was elected, in part—I had to get what I got, and a lot of people who voted for me were Democrats, and some were African Americans who were friends and who thought I would be fair and be a new, fresh face in politics for our state and not be tied to any previous political decisions. I’d be free to vote like I thought I should in the interest of this district. It was about 38 percent black in population, maybe 40 percent, and not only did I win that, but then the challenge was to get re-elected after you’ve made everybody in the Democratic hierarchy mad. I knew they were going to come out with all guns blazing, and they did, but they couldn’t get a candidate. They couldn’t recruit a good candidate. They finally got a candidate but—

Knott

Seventy-four was a rough year for Republicans.

Cochran

It was and, of course, Republicans were getting beat right and left. So when we came back up here to organize after that election in ’74, there weren’t enough Republicans to count. But I was one of them who was here and who was back. Senator Lott, he and I both made it back okay. He was from a more-Republican area: fewer blacks and more supportive of traditional Republican issues.

His opinion on the state of affairs:

Serving in the Senate has gotten to be almost a contact sport, and that’s regrettable, in my view. I would like for it to be more like it was when I first came to the Senate. There was partisanship, right enough, and if you were in the majority, you got to be chairman of all the subcommittees, and none of the Republicans, in my first two years, were chairmen of anything, but that’s fine. That’s the way the House is operated. I’d seen that in the House, and that’s okay. Everybody understands it. But since it’s become so competitive—and the House has too—things are more sharply divided along partisan lines than they ever have been in my memory, and I think the process has suffered. The legislative work product has deteriorated to the point that legislation tends to serve the political interests of one party or the other, and that’s not the way it should be.

Who does he blame?:

I’ve been disappointed in the partisanship that has deteriorated to the point of pure partisanship in court selections, in my opinion, in the last few years, and [Ted Kennedy’s] been a part of that. I’m not fussing at him or complaining about it. It’s just something that has evolved, but all the Democrats seem to line up in unison to badger and embarrass and beat up Republican nominees for the Supreme Court in particular. But it’s extended to other courts, the court of appeals. They all lined up and went after Charles Pickering from my state unfairly, unjustly, without any real reason why he shouldn’t be confirmed to serve on the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. He had run against me when I ran for the Senate, Pickering had. I defeated him in the Republican primary in 1978. So we haven’t been political allies, but I could see through a lot of the things.

I have a close personal friendship with Pat Leahy and Joe Biden, and I could probably name a few others. I’ve really been aggravated with them all for that reason, and I hope that we’ll see some modification of behavior patterns in the Judiciary Committee. Occasionally they’ll help me with somebody. I’m going to be presenting a candidate for a district court judgeship this afternoon in the committee, and yesterday Pat came up, put his arm around me, and said,

I know you’re for this fellow, [Leslie] Southwick, who is going to be before the committee, and I want you to know you can count on me.Well, I’m glad to hear that.There’s nothing wrong with him. I mean, he’s a totally wonderful person in every way. He’ll be a wonderful district judge.I’m not saying that they make a habit of it, but they’ve picked out some really fine, outstanding people to go after here recently, and there are probably going to be others down the line that they’ll do that. Ted’s part of that, and I think all the Democrats do it. I think that’s unfortunate.

Knott

Are they responding to interest group pressure? Is that your assessment?

Cochran

I think that has something to do with it, but I’m not going to suggest what the motives are or why they’re doing it, but it’s just a fact. It’s pure partisan politics, and it’s brutal, mean-spirited, and I don’t like it.

Heininger

What do you attribute the change to?

Cochran

I don’t know. I guess one reason is we’re so closely divided now. You know, just a few states can swing control of the Senate from one party to the next, and we have been such a closely divided Senate now for the last ten years or so. Everybody understands the power that comes with being in the majority, and I’m sure both parties have taken advantage of the situation and have maybe been unfair in the treatment of members of the minority party, denying them privileges and keeping their amendments from being brought up or trying to manage the schedule to the benefit of one side or the other.

Cochran died in 2019. In the Senate he used Jefferson Davis’s desk.

Sinalco

Posted: October 29, 2022 Filed under: Mississippi, WOR Leave a comment

Saw this old sign in Corinth, Mississippi. You can’t find a Sin Alco in the United States these days but apparently it’s still the third most popular soda in Germany.

Both Corinth and Vicksburg, Mississippi have Coca-Cola related museums, and of course Atlanta is all about Coke. It got me wondering if the spread of Coca-Cola was connected to the total devastation of the South in the wake of the Civil War. Recall that Coca-Cola was invented by John Stith Pemberton, a former Confederate officer wounded in the war who was experimenting with increasingly wild home brews in an effort to cure himself of morphine addiction. There were a lot of people around with shattered nerves looking for a tonic. There was a big demand for alternatives to alcohol:

The first successful effort to limit the sale of alcohol was an 1874 law that required anyone wanting to sell alcohol to obtain a license from a majority of the area’s registered voters plus a majority of all women over age fourteen

From the Mississippi Encyclopedia. In law if not in practice Mississippi went dry in 1908. (That’s part of why the river towns on the Arkansas side got so wild).

Strange and haunting to visit these parts of the country that were ruined by defeat in war and an occupying army. When you wonder why Jackson, MS is so messed up it’s worth remembering the city was burnt to the ground not once but twice during the war, nothing standing but a few brick chimneys. Maybe they should have their mess together by now, but it’s only a few generations ago. Irene Triplett was getting a Civil War pension two years ago.

Good slogan for a soda: “You’ll Like It”

Stagolee Shot Billy

Posted: December 25, 2020 Filed under: Mississippi, music, Nick Cave Leave a commentIn a St. Louis tavern on Christmas night in 1895 Lee Shelton (a pimp also known as Stack Lee) killed William Lyons in a fight over a hat. There were other murders that night, but this one became the stuff of legend. Songs based on the event soon spread out of whorehouses and ragtime dives across the country. Within 40 years, Stagolee had evolved into a folk hero, a symbol of rebellion for black American males. With commendable scholarship and thoroughness, Brown shows how we got from the murder to the myth.

so says Leopold Froehlich in Playboy, quoted on the book’s back cover. I’ve been curious about this book since I first heard about it, finally pulled the trigger. Just that a book like this exists brings joy.

The murder was around 11th and Morgan in St. Louis, which today looks like this:

Should it be a UNESCO site? Paired perhaps with another St. Louis place of myth and violence, Cahokia?

Conversations with Faulkner

Posted: September 7, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, Hollywood, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Alcohol was his salve against a modern world he saw as a conspiracy of mediocrity on its ruling levels. Life was most bearable, he repeated, at its simplest: fishing, hunting, talking biggity in a cane chair on a board sidewalk, or horse-trading, gossiping.

Bill spoke rarely about writing, but when he did he said he had no method, no formula. He started with some local event, a well-known face, a sudden reaction to a joke or an incident. “And just let the story carry itself. I walk along behind and write down what happens.”

Origin story:

Q: Sir, I would like to know exactly what it was that inspired you to become a writer.

A: Well, I probably was born with the liking for inventing stories. I took it up in 1920. I lived in New Orleans, I was working for a bootlegger. He had a launch that I would take down the Pontchartrain into the gulf to an island where the run, the green rum, would be brought up from Cuba and buried, and we would dig it up and bring it back to New Orleans, and he would make scotch or gin or whatever he wanted. He had the bottles labeled and everything. And I would get a hundred dollars a trip for that, and I didn’t need much money, so I would get along until I ran out of money again. And I met Sherwood Anderson by chance, and we took to each other from the first. I’d meet him in the afternoon, we would walk and he would talk and I would listen. In the evening we would go somewhere to a speakeasy and drink, and he would talk and I would listen. The next morning he would say, “Well I have to work in the morning,” so I wouldn’t see him until the next afternoon. And I thought if that’s the sort of life writers lead, that’s the life for me. So I wrote a book and, as soon as I started, I found out it was fun. And I hand’t seen him and Mrs. Anderson for some time until I met her on the street, and she said, “Are you mad at us?” and I said, “No, ma’am, I’m writing a book,” and she said, “Good Lord!” I saw her again, still having fun writing the book, and she said, “Do you want Sherwood to see your book when you finish it?” and I said, “Well, I hadn’t thought about it.” She said, “Well, he will make a trade with you; if he don’t have to read that book, he will tell his publisher to take it.” I said, “Done!” So I finished the book and he told Liveright to take it and Liveright took it. And that was how I became a writer – that was the mechanics of it.

Stephen Longstreet reports on Faulkner in Hollywood, specifically To Have and Have Not:

Several other writers contributed, but Bill turned out the most pages, even if they were not all used. This made Bill a problem child.

The unofficial Writers’ Guild strawboss on the lot came to me.

“Faulkner is turning out too many pages. He sits up all night sometimes writing and turns in fifty to sixty pages in the morning. Try and speak to him.”

Conversations With series from the University Press of Mississippi

Posted: August 31, 2020 Filed under: advice, America Since 1945, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment This is one my favorite books, I’m serious. Shelby Foote is a great interview, obviously, just watch his interviews with Ken Burns. (“Ken, you made me a millionaire,” Shelby reports telling Burns after the series aired.) You may not want to read the whole of Shelby’s three volume Civil War, it can get carried away with the lyrical, and following the geography can be a challenge. But the flavor of it, some of the most vivid moments, and anecdotes, come through in these collected conversations with inquirers over the years.

This is one my favorite books, I’m serious. Shelby Foote is a great interview, obviously, just watch his interviews with Ken Burns. (“Ken, you made me a millionaire,” Shelby reports telling Burns after the series aired.) You may not want to read the whole of Shelby’s three volume Civil War, it can get carried away with the lyrical, and following the geography can be a challenge. But the flavor of it, some of the most vivid moments, and anecdotes, come through in these collected conversations with inquirers over the years.

“You’ve got to remember that the Civil War was as big as life,” he explains. “That’s why no historian has ever done it justice, or ever will. But that’s the glory of it. Take me: I was raised up believing Yankees were a bunch of thieves. But it’s absolutely incredible that a people could fight a Civil War and have so few atrocities.

“Sherman marched with 60,000 men slap across Georgia, then straight up though the Carolinas, burning, looting, doing everything in the world – but I don’t know of a single case of rape. That’s amazing because hatreds run high in civil wars…

There were still a lot of antique virtues around them. Jackson once told a colonel to advance his regiment across a field being riddled by bullets. When the officer protested that nobody could survive out there, Jackson told him he always took care of his wounded and buried his dead. The colonel led his troops into the field.”

Finally treated myself to a few more of these editions. These books are casual and comfortable. They’re collections of interviews from panels, newspapers, magazines, literary journals, conference discussions. Physically they’re just the right size, the printing is quality and the typeface is appealing.

Why not start with another Mississippian, someone Foote had quite a few conversations with himself?

Wow, Walker Percy could converse.

Later, different interview:

Do we dare attempt conversation with the father of them all?

I’ve long found interviews with Faulkner, even stray details from the life of Faulkner, to be more compelling than his fiction. Maybe it’s the appealing lifestyle: courtly freedom, hunting, fishing, and all the whiskey you can handle. The life of an unbothered country squire, preserving a great tradition, going to Hollywood from time to time, turning the places of your boyhood into a world mythology.

We’ll have more to say about the Conversations with Faulkner, deserves its own post! Maybe Percy gets to the heart of it in one of his interviews:

Q: Did you serve a long apprenticeship in becoming a writer?

Percy: Well, I wrote a couple of bad novels which no one wanted to buy. And I can’t imagine anyboy doing anything else. Yes it was a long apprenticeship with some frustration. But I was lucky with the third one, The Moviegoer; so, it wasn’t so bad, I guess.

Q: Had you rather be a writer than a doctor?

Percy: Let’s just say I was the happiest doctor who ever got tuberculosis and was able to quit it. It gave me an excuse to do what I wanted to do. I guess I’m like Faulkner in that respect. You know Faulkner lived for awhile in the French Quarter of New Orleans where he met Sherwood Anderson, and Faulkner used to say if anybody could live like that and get away with it he wanted to live the same way.

There’s one of these for you, I’m sure. They also have Comic Artists and Filmmakers.

only one subject with whom I myself had a conversation

For the advanced student:

Delta

Posted: June 16, 2019 Filed under: America Since 1945, Mississippi, music Leave a comment

ruins of Windsor Plantation

Found myself, for the second time in two years, driving Highway 61 through the Mississippi Delta. I don’t feel like I intended this, exactly. Once was good. But there I was again.

This map by Raven Maps was a breakthrough in understanding the Delta, what makes this region freakish and weird and unique. The Delta is low-lying bottomland. Thinking of the Mississippi in this area as a line on a map is inaccurate, it’s more like a periodically swelling and retreating wetland, like the Amazon or the Nile. Floods are frequent, vegetation grows thick, the soil is rich and good for growing cotton. That is the curse, blessing and history of the Delta. This year Highway 61 was almost flooded below Vicksburg.

The river from the bluffs at Natchez

The Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg. The Peabody is the Paris Ritz, the Cairo Shepheard’s, the London Savoy of this section. If you stand near its fountain in the middle of the lobby, where ducks waddle and turtles drowse, ultimately you will see everybody who is anybody in the Delta and many who are on the make.

So said David Cohn in his famous essay of 1935.

It’s been awhile since I was at The Peabody.

Dave Cohn was Jewish. Shelby Foote had a Jewish grandfather. The Delta was diverse.

So says Shelby. On the Delta fondness for canned beans:

from:

Here’s something North Mississippi Hill Country man Faulkner had to say about people in this region:

Q: Well, in the swamp, three of the men that lived in the swamp did have names – Tine and Toto and Theule, and I wonder if those names had any type of significance or were supposed to be any type of literary allusion. They’re rather colorful names, I think.

A: No, I don’t think so. They were names, you might say, indigenous to that almost unhuman class of people which live between the Mississippi River and the levee. They belong to no state, they belong to no nation. They – they’re not citizens of anything, and sometimes they behave like they don’t even belong to the human race.

Q: You have had experience with these people?

A: Yes. Yes, I remember once one of them was going to take me hunting. He invited me to come and stay with his kinfolks – whatever kin they were I never did know – a shanty boat in the river, and I remember the next morning for breakfast we had a bought chocolate cake and a cold possum and corn whiskey. They had given me the best they had. I was company. They had given me the best food they had.

The Delta is a ghost town. In 2013 The Economist reported

Between 2000 and 2010 16 Delta counties lost between 10% and 38% of their population. Since 1940, 12 of those counties have lost between 50% of 75% of their people.

Another Economist piece from the same era has a great graphic of this:

“You can’t out-poor the Delta,” says Christopher Masingill, joint head of the Delta Regional Authority, a development agency. In parts of it, he says, people have a lower life expectancy than in Tanzania; other areas do not yet have proper sanitation.

Everywhere you see abandoned buildings, rotting shacks, collapsing farmhouses. This gives the place a spooky quality. It’s like coming across the shedding shell of a cicada. There are signs of a once-rich life that is gone.

Here’s an amazing post about the sunken ruins of the plantation of Jefferson Davis.

Every town that still exists along the river of the Delta is on high ground or a bluff. Natchez, Port Gibson, Vicksburg. Once beneath these towns there were great temporary floating communities of keelboats, canoes. But the river has flooded and receded and changed its course many times. Charting the historical geography of these towns is confusing. Whole towns have disappeared, or been swallowed.

Brunswick Landing, of which nothing remains.

The first time I ever thought about the Mississippi Delta was when I came across this R. Crumb cartoon about Charley Patton, who was from Sunflower County.

Something like 2,000 people lived and worked at Dockery Plantation. It’s worth noting that this plantation was started after slavery, it was begun in 1895.

At the time, much of the Delta area was still a wilderness of cypress and gum trees, roamed by panthers and wolves and plagued with mosquitoes. The land was gradually cleared and drained for cotton cultivation, which encouraged an influx of black labourers.

In a way, the blues era, say 1900-1940 or so, was a kind of boomtime in the Delta. The blues can be presented as a music of misery and pain but what if it was also a music of prosperity? Music for Saturday night on payday, music for when recording first reached communities exploding with energy? Music from the last period of big employment before mechanization took the labor out of cotton? How much did the Sears mail order catalog help create the Delta blues?

We stopped at Hopson Commissary in Clarksdale, once the commissary of the Hopson plantation. (Once did someone run to get cigarettes from there?) Here was the first fully mechanized cotton harvest – where the boomtime peaked, and ended. If you left Mississippi around this time, you probably left on the train from Clarksdale.

If in Clarksdale I can also recommend staying at The Delta Bohemian guest house. We were company and they gave us their best.

you may need this number

Here’s something weird we saw, near Natchez:

We listened to multiple podcasts about Robert Johnson selling his soul at the crossroads, that whole bit. The interesting part of the story (to me) is that, according to the memories of those who knew him, Robert Johnson did somehow, suddenly, get way better at the guitar. I like this take the best:

Some scholars have argued that the devil in these songs may refer not only to the Christian figure of Satan but also to the African trickster god Legba, himself associated with crossroads. Folklorist Harry M. Hyatt wrote that, during his research in the South from 1935 to 1939, when African-Americans born in the 19th or early 20th century said they or anyone else had “sold their soul to the devil at the crossroads,” they had a different meaning in mind. Hyatt claimed there was evidence indicating African religious retentions surrounding Legba and the making of a “deal” (not selling the soul in the same sense as in the Faustian tradition cited by Graves) with the so-called devil at the crossroads.

Does everybody in the music business sell their soul to the Devil, one way or another?

Is there something vaguely embarrassing about white obsession with old blues? I get the yearning to connect to a past that sounds like it’s almost disappeared, where just the barest, rawest trace echoes through time. But doesn’t all this come a little too close to taking a twisted pleasure in misery? And is there something a little gloves-on, safe remove about focusing on music from eighty years ago, when presumably somewhere out there real life people are creating vital music, right now?

I dunno, maybe there’s something cool and powerful about how lonely nerds and collectors somewhere and like tourists from Belgium connecting to the sounds of desperate emotion from long dead agricultural workers.

My favorite of the old blues songs is Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground. Blind Willie Johnson wasn’t even from the Delta though, he was from Pendleton, Texas.