Hundred in the Hand

Posted: July 22, 2023 Filed under: murders, mysteries, native america, the American West, war Leave a comment

The Sioux were of two minds about winktes but considered them mysterious (wakan) and called on them for certain kinds of magic or sacred power. Sometimes winktes were asked to name children, for which the price was a horse. Sometimes they were asked to read the future. On December 20, 1866, the Sioux, preparing another attack on the soldiers at Fort Phil Kearny, dispatched a winkte on a sorrel horse on a symbolic scout for the enemy. He rode with a black cloth over his head, blowing on a sacred whistle made from the wing bone of an eagle as he dashed back and forth over the landscape, then returned to a group of chiefs with his fist clenched and saying, “I have ten men, five in each hand – do you want them?”

The chiefs said no, that was not enough, they had come ready to fight more enemies than that, and they sent the winkte out again.

Twice more he dashed off on a sorrel horse, blowing his eagle-bone whistle, but each time the number of enemy he brought back in his fists was not enough. When he came back the fourth time he shouted, “Answer me quickly – I have a hundred or more.” At this all the Indians began to shout and yell, and after the battle the next day it was often called the Battle of a Hundred in the Hand.

– so writes Thomas Powers in The Killing of Crazy Horse. In a footnote Powers says “This version of the story of the winkte was told to George Bird Grinnell in 1914 by the Cheyenne White Elk, who took part in the Fetterman fight when he was about seventeen years old. It can be found in George Bird Grinnell, The Fighting Cheyennes, 237-8.” You can also find White Elk’s testimony in Eyewitness to the Fetterman Fight: Indian Views, edited by John H. Monnett and published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

On the morning of the 21st ultimo at about 11 o’clock A.M. my picket on Pilot hill reported the wood train corralled, and threatened by Indians on Sullivan Hills, a mile and a half from the fort. A few shots were heard. Indians also appeared in the brush at the crossing of Piney, by the Virginia City road…

Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman also was well admonished, as well as myself, that we were fighting brave and desperate enemies who sought to make up by cunning and deceit, all the advantages which the white man gains by intelligence and better arms.

Hence my instructions to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman, viz: – “Support the wood train, relieve it and report to me. Do not engage or pursue Indians at its expense. Under no circumstances pursue over the ridge viz; Lodge Trail Ridge, as per map in your possession.”

At 12 o’clock firing was heard towards Peno Creek, beyond Lodge Trail Ridge. A few shots were followed by constant shots, not to be counted. Captain Ten Eyck was immediately dispatched with infantry and the remaining cavalry and two wagons, and ordered to join Colonel Fetterman at all hazards.

The men moved promptly and on the run, but within little more than half an hour from the first shot, and just as the supporting party reached the hill overlooking the scene of action, all firing ceased.

Captain Ten Eyck sent a mounted orderly back with the report that he could see and hear nothing of Fetterman, but that a body of Indians, on the road below him, were challenging him to come down, while larger bodies were in all the valleys for several miles around.

Moving cautiously forward with the wagons, evidently supposed by the enemy to be guns, as mounted men were in advance, he rescued from the spot where the enemy had been nearest, forty nine bodies, including those of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman and Captain F.H. Brown. …

The following morning, finding genuine doubt as to the success of an attempt to recover other bodies, but believing that failure to rescue them would dishearten the command and encourage the Indians who are so particular in this regard, I took eighty men and went to the scene of action..

The scene of action told its story. The road on the little ridge where the final stand took place was strewn with arrow heads, scalps, poles and broken shafts of spears. The arrows that were spent harmlessly from all directions, showed that the command was suddenly overwhelmed, surrounded and cut off while in retreat. Not officer or man survived. A few bodies were found at the north end of the divide over which the road runs just below Lodge Trail Ridge.

…

Fetterman and Brown had each a revolver shot in the left temple. As Brown always declared he would reserve a shot for himself as a last resort, so I am convinced that these two brave men fell, each by the other’s hand, rather than undergo the slow torture inflicted upon others…

The officers who fell believed that no Indian force could overwhelm that number of troops well held in hand.

…

Pools of blood on the road and sloping sides of the narrow divide showed where Indians bled fatally, but their bodies were carried off. I counted sixty five such pools in the space of an acre, and three within ten feet of Lieut. Grummond’s body.

At the northwest or further point, between two rocks, and apparently where the command first fell back from the valley, realizing their danger, I found citizen James S. Wheatly and Isaac Fisher of Blue Springs Nebraska, who, with “Henry rifles”, felt invincible, but fell, one having one hundred and five arrows in his naked body.

The widow and family of Wheatly are here. The cartridge shells about him, told how well they fought.

…

…

I was asked to “send all the bad news”. I do it as far as I can. I give some of the facts as to my men whose bodies I found just at dark, resolved to bring all in viz: –

Mutilations

Eyes torn out and laid on the rocks.

Noses cut off.

Ears cut off.

Chins hewn off.

Teeth chopped out.

Joints of fingers. [sic]Brains taken out and placed on rocks with other members of the body.

Entrails taken out and exposed.

Hands cut off.

Feet cut off.

Arms taken out from socket.

Private parts severed and indecently placed on the person.

Eyes, ears, mouth, and arms penetrated with spear heads, sticks and arrows.

Ribs slashed to separation with knifes.

Sculls [sic] severed in every form from chin to crown.

Muscles of calves, thighs, stomach, breast, back, arms and cheek, taken out.

Punctures upon every sensitive part of the body, even to the soles of the feet and palms of the hand.All this only approximates to the whole truth.

so wrote Colonel H. B Carrington in his report dated Jan 3, 1867, which you can find for yourself here if you’re so inclined.

Fetterman’s march ended on a knoll beside U.S. 87 a few miles below Sheridan—less than a hundred miles from Custer’s blind alley. Today a rough stone barricade encloses the site. A flagpole stands beside a cairn emblazoned with a bronze shield and a summary of the disaster. One farmhouse can be seen about a mile up the road, otherwise there is nothing to look at except a line of telephone poles. Not many people use the old highway, traffic cruises along 1-90 some distance east. Very few tourists leave the freeway to commune with the shade of this arrogant officer who, like Lt. Grattan twelve years earlier, thought a handful of bluecoats could ride straight through the Sioux nation. The black iron gate to this memorial frequently hangs open.

Capt. Fetterman was sucked to death by a stratagem antedating the Punic wars. He met a weak party of Oglalas just out of reach. Naturally he chased them. He almost caught them. A few yards farther—a few more yards. It is said that young Crazy Horse was among these decoys.

Meanwhile, the woodcutters got back safely. Fetterman could not have been very bright because two weeks earlier the Sioux just about bagged him in a similar ambush. From that experience he learned nothing. He entered the trap again. Why? Because he was new to the frontier, because of constitutional arrogance, perhaps because he had been educated at West Point to assume that one American soldier could handle a dozen savages. And he might possibly have been enraged by the decoys shouting in English: “You sons of bitches!”

Dunn, whose ponderous history of these sanguine days appeared in 1886, claims that many years after the fight he was shown an oak war club bristling with spikes—still clotted with blood, hair, and dried brains—which the Oglalas used on Fetterman’s troops. He does not excuse Fetterman, but at the same time he has no very high opinion of Col. Carrington, whom he labels a dress-parade officer. Carrington should not have been assigned to the frontier, says Dunn, he should have been teaching school: “He built a very nice fort, but every attack made on him and his men, during the building, was a surprise. There is nothing to indicate that he ever knew whether there were a thousand or only a hundred Indians within a mile of the fort. He seems to have disapproved of Indians. Perhaps he would have ostracized them socially, if he could have had his way.”

Two experienced civilians, James Wheatley and Isaac Fisher, had joined the party in order to try out their new sixteen-shot Henry repeating rifles. These men especially infuriated the Sioux, probably because they punctured a good many of Red Cloud’s finest before being dropped. Identification was tentative because their faces were reduced to pudding, and one of them—scholars disagree as to which—had been spitted with 105 arrows.

…

John Guthrie was one of the first troopers on the scene. He noted his impressions in a convulsive, agitated style. He wrote that the command lay on the old Holiday coach road near Stoney Creek ford just over a mile from the fort—which is not quite accurate, the true distance being at least twice that far.

The fate of Colonel Fetterman command all my comrades of the detail could see, the Indians on the bluff, the silver flashed with the glorious sunshine, flashed in the hair of the skulking Indians carrying away the clothing of the butchered, with arrows sticking in them, and a number of wolves, hyenas and coyotes hanging about to feast on the flesh of the dead men’s bodies. The dead bodies of our friends at the massacre lay out all night and were not touched or disturbed in any way again, and the cavalry horse of Co. C 2nd, those ferocious and devourers of bodies, did not even touch. Another rather peculiar feature in connection with those massacres is that it is thought by some that those wild animals that eat the dead bodies of the Indians are not so apt to disturb the white victims, and this is accounted for by the fact that salt generally permeates the whole system of the white race, and at least seems to protect to some extent even after death, from the practice of wild animals. Twenty four hours after death Dr. Report at Fort detailed we start to load the dead on the ammunition, all of the Fetterman boys huddled together on the small hill and rock some small trees nearly shot away on the old coach road, near the battle field or Massacre Hill, ammunition boxes we packed them, my comrades on top of the boxes terrible cuts left by the Indians, could not tell Cavalry from the Infantry, all dead bodies stripped naked, crushed skulls, with war clubs ears and noses and legs had been cut off, scalps torn away and the bodies pierced with bullets and arrows, wrist feet and ankles leaving each attached by a tendon. We loaded the officers first. Col. Fetterman of the 27th Infantry, Captain Brown of the 18th Infantry and bugler Footer of Co. C 2nd Cavalry were all huddled together near the rocks, Footer’s skull crushed in, his body on top of the officers … . Sargeant Baker of Co. C 2nd Cavalry, a gunnie sack over his head not scalped, little finger cut off for a gold ring; Lee Bontee the guide found in the brush near by the rest called Little Goose Creek, body full of arrows which had to be broken off to load him … . Some had crosses cut on their breasts, faces to the sky, some crosses cut on the back, face to the ground, a mark cut that we could not find out. We walked on top of their internals and did not know it in the high grass. Picked them up, that is their internals, did not know the soldier they belonged to, so you see the cavalry man got an infantry man’s gutts and an infantry man got a cavalry man’s gutts … .

Only one man, bugler Adolph Metzger, had not been touched. His bugle was so badly dented that he must have gone down swinging it like a club, and for some reason the Indians covered his body with a buffalo robe.

Years later an Oglala named Fire Thunder, who had been sixteen at the time, described with eloquent simplicity the Indian trap. He said that after finding a good place to fight they hid in gullies along both sides of the ridge and sent a few men ahead to coax the soldiers out. After a long wait they heard a shot, which meant soldiers were coming, so they held the nostrils of their ponies to keep them from whinnying at the sight of the American horses. Pretty soon the Oglala decoys came into view. Some were on foot, leading their ponies to make the soldiers think the ponies were tired. Soldiers chased them. The air filled with bullets. But all at once there were more arrows than bullets—so many arrows that they looked like grasshoppers falling on the soldiers. The American horses got loose, Fire Thunder said. Several Indians went after them. He himself did not because he was after wasichus. There was a dog with the soldiers which ran howling up the road toward the fort, but died full of arrows. Horses, dead soldiers, wounded Indians were scattered across the hill “and their blood was frozen, for a storm had come up and it was very cold and getting colder all the time.” Then the Indians picked up their wounded and went away. The ground felt solid underfoot because of the cold. That night there was a blizzard.

– so says Evan S. Connell in Son of the Morning Star.

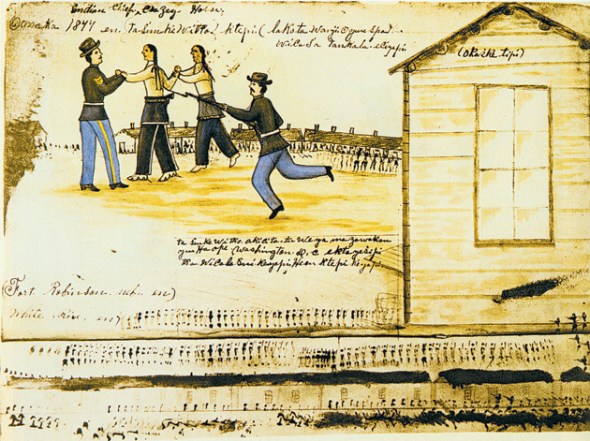

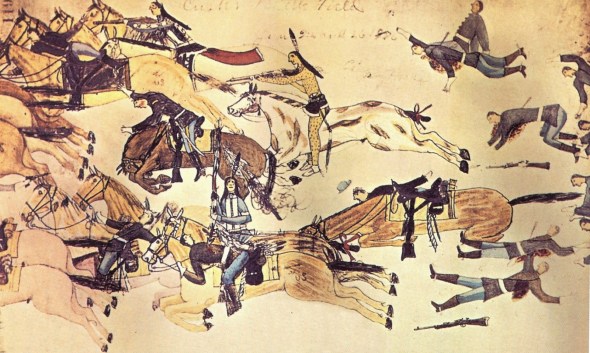

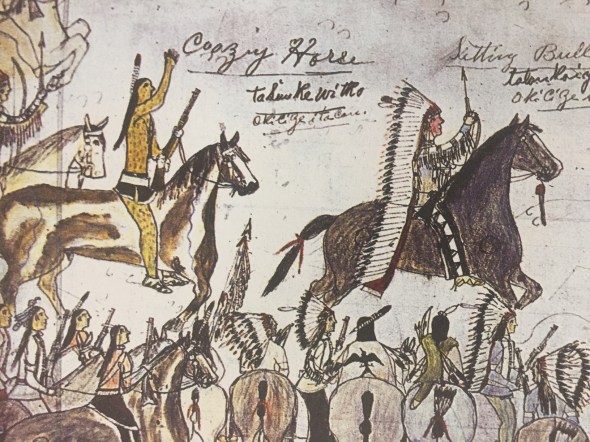

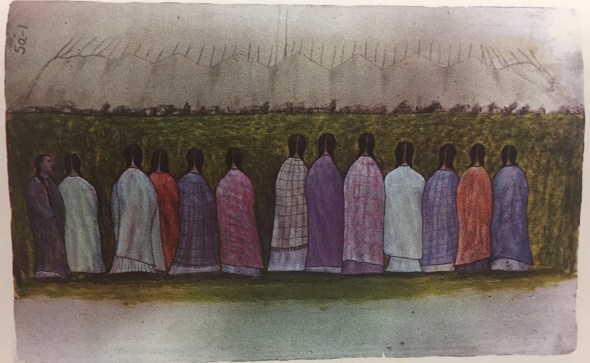

American Horse (the elder?) drew a representation of the event in a winter count that’s now in the collection of the Smithsonian:

Red Cloud and other Oglala Sioux who took part in that whirlwind affair talked of it afterward to Captain James Cook, who resided for many years near their Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota. Cook says they told him that the white soldiers seemed paralyzed, offered no resistance, and were simply knocked in the head. Old Northern Cheyenne Indians who were there have talked of it to the author. They say that Crazy Mule, a noted Cheyenne worker of magic, performed one of his miracles on that occasion. He caused the soldiers to become dizzy and bewildered, to run aimlessly here or there, to drop their guns, and to fall dead.

– Thomas Marquis in Keep The Last Bullet For Yourself, a valuable source with a provocative title. The manuscript was only published years after Marquis died. Marquis was a doctor on the Northern Cheyenne reservation and spoke to many eyewitnesses.

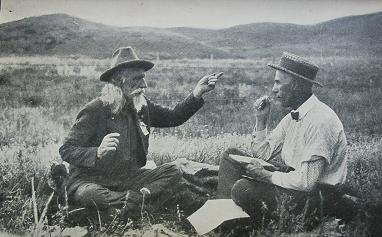

Marquis hearing from the old scout Tom Leforge, from Marquis wiki page

Eerie events on the American plains.

Picture of the site from Google Street View.

Göpeti Tepli, Askili Höyük, and Chaco Canyon

Posted: December 15, 2020 Filed under: archaeology, native america, New Mexico Leave a comment

Reading up on some of these Turkish archaeological sites. Göbekli Tepe is sometimes described as “the world’s oldest town,” but it may have been more like a ritual site that people went to sometimes, rather than lived in all the time. I’m not totally up on recent archaeological literature about the sites, but they seem to have been something more like seasonal or periodic gathering places. This was around 9,000 BCE.

Askili Höyük, similar deal.

People who were still hunter gatherers, or at least semi-nomadic, would gather seasonally or sometimes at these places, to build, do ceremonies maybe, and party.

The time frame is completely off, but I wonder if the concept of these sites can be applied to Chaco Canyon, in what’s now New Mexico, which was peaking in around 900 AD.

Steve Lekson, who wrote several books on Chaco and the ancient Southwest, suggests Chaco was more permanent, something like a Mesoamerican city state.

Jared Diamond, in Collapse, presents Chaco in “city” terms as well.

But what if it was more like the playa of Burning Man than like Chichen Itza or Teotihuacan?

If it wasn’t a city, but a ceremonial/festival/party location for people who were still semi-nomadic?

Or what if it were a city, but one like Las Vegas, with locals who ran the place but a big, shifting population of tourists?

What if there’s a stage between “primitive hunter gatherer bands” and “agricultural early cities” that’s like “semi agricultural nomads who occasionally meet to party”? Just musing!

Diné

Posted: March 13, 2020 Filed under: America, language, native america Leave a comment

Sapir’s special focus among American languages was in the Athabaskan languages, a family which especially fascinated him. In a private letter, he wrote: “Dene is probably the son-of-a-bitchiest language in America to actually know…most fascinating of all languages ever invented.”

I’ve been doing some work to learn:

- how it was that Navajo got to be classified as an Athabaskan language and

- what linguistic evidence exists for the northern origins of the Navajo.

This is a good journey, but challenging.

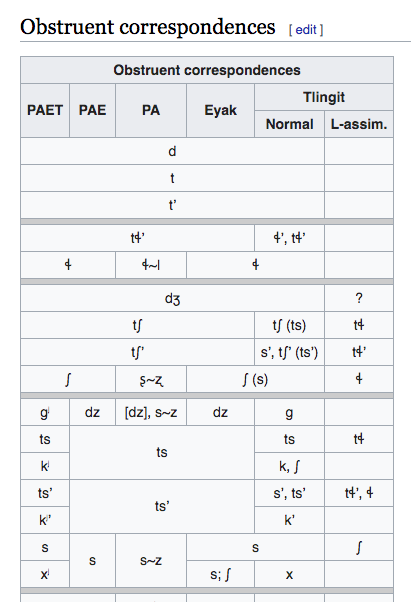

Sometimes it leads me to stuff like this:

which: ok, how much can we trust these linguists? Are we sure we’re on solid ground here?

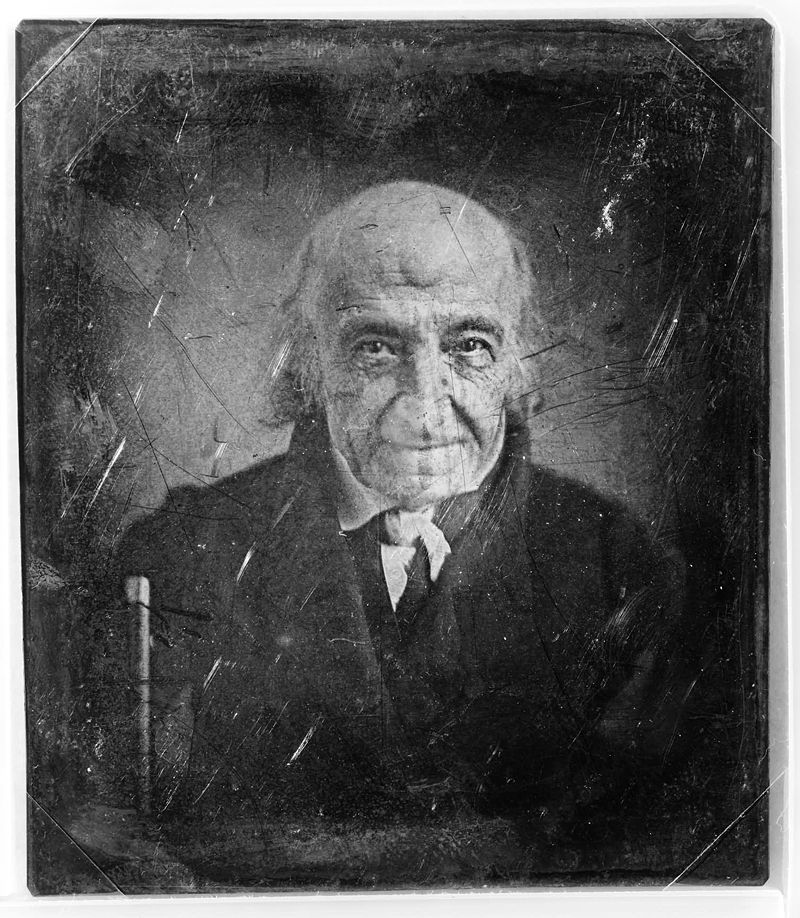

The big categorizing of native American languages was done by Albert Gallatin in the 1830s.

Could he have been wrong? People were wrong a lot back then.

Well, after looking it with an amateur’s enthusiasm, I feel more trusting.

I feel confident Navajo/Diné is connected to languages of what’s now Alaska, British Columbia, and nearby turf.

Navajo / Diné speakers can be understood by speakers of other Athabaskan languages, and most of the words in Navajo seem to have Athabaskan origin.

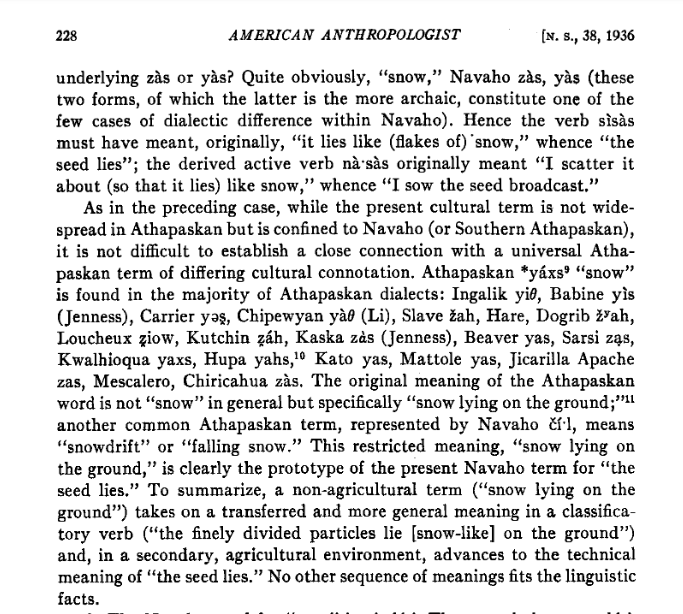

Edward Sapir wrote a paper about internal evidence within the Navajo language for a northern origin to this people.

Sapir was wrong* about some things, but no one seems to doubt he was a pretty serious linguist.

How about Michael E. Krauss?

After completing a dissertation on Gaelic languages Krauss arrived in Alaska in 1960 to teach French at the University of Alaska.

Krauss’ largest contribution to language documentation is his work on Eyak, which began in 1961. Eyak was then already the most endangered of the Alaskan languages, and Krauss’ work is all the more notable considering that it represents what today might be considered salvage linguistics. While some Eyak data had been previously available, they were overlooked by previous scholars, including Edward Sapir. However, Eyak proved to be a crucial missing link for historical linguistics, being equally closely related to neighboring Ahtna and to distant Navajo. With good Eyak data it became possible to establish the existence of the Athabaskan–Eyak–Tlingit language family, though phonological evidence for links to Haida remained elusive.

If anyone makes any progress on native American language classifications while under precautionary self-quarantine, let us know

* I’m just teasing poor Sapir here, I don’t think it’s fair to “blame” him exactly for the “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis,” which maybe isn’t even wrong, and as far as I can tell it was Whorf not Sapir who misunderstood Hopi

Sipapu

Posted: February 20, 2020 Filed under: native america, New Mexico, skiing Leave a commentI was at the bar in Santa Fe, New Mexico watching the national college football championship game, eating nachos and drinking beer. A small place, the atmosphere was social, and the guy next to me got to talking about skiing. He mentioned a small mountain called Sipapu. They’d just had some fresh snow and he made it sound so good. “It’s real small.” “Almost a local’s only mountain.” “They have great blues.” The only thing I had to do the next day was have lunch at 1pm, so I thought well heck, why don’t I wake up early and drive up there?

So that’s what I did, I woke up and drove up there very early, up past Chimayo and Abiquiu, in the Kit Carson National Forest. The spot was small and nothing fancy, there’s nowhere to stay up there, renting skis was kind of a rickety procedure. But once you got going it was beautiful, the sky was clear and blue, warm and the snow was soft.

I tried out the portrait mode on my phone.

Mostly, I had the place to myself.

I didn’t think much about the name, Sipapu, although I liked it. I said it in my head, alone on the chairlift. Sipapu.

Later I was home I was looking through this book:

From the glossary:

Sipapu.

Cahokia news

Posted: February 6, 2020 Filed under: archaeology, native america Leave a comment

Don’t get too excited by the headline over at Phys.org. What they really seem to have found is that people continued to live in the Cahokia region even after the big population center “collapsed” or sort of dwindled out.

I call your attention to this article because it highlights what I love about archaeology: the extremes of methodology. You read this and you’re like cool, new light on an ancient city. How did they find it out?

To collect the evidence, White and colleagues paddled out into Horseshoe Lake, which is adjacent to Cahokia Mounds State Historical Site, and dug up core samples of mud some 10 feet below the lakebed. By measuring concentrations of fecal stanols, they were able to gauge population changes from the Mississippian period through European contact.

These people are paddling out into a lake, dredging up mud, and testing it for human shit.

You know what? There are worse ways to spend an afternoon. There’s something so deeply funny and human about thinking that maybe in a thousand years or so some archaeologist will be studying your stool to find out what the hell you were up to.

The Riddle of Chaco Canyon

Posted: December 3, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, desert, native america Leave a comment

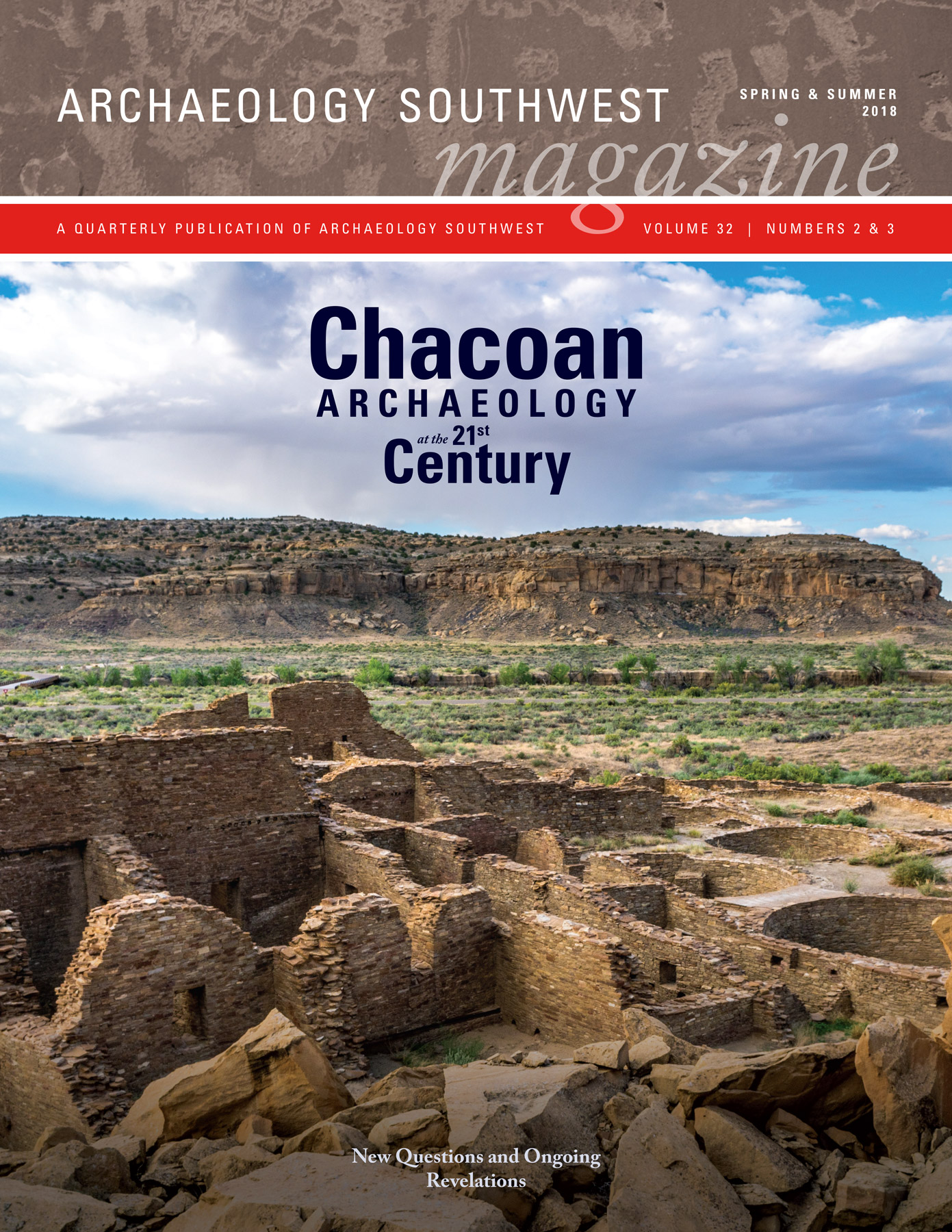

Sure, we’ve all heard of Chaco Canyon. It’s one of the 23 UNESCO World Heritage sites in the USA. But I tended to lump it in with Mesa Verde and the other cliff dwellings and move on.

Then an ad in High West (“for people who care about the West”) caught my eye. $25 for a year’s subscription to Archaeology Southwest, PLUS the Chaco archaeology report? Yes!

Once you get going on Chaco Canyon, it’s hard to stop.

Bob Adams at Wikipedia

What was it? Who built it? How? What happened? What were they up to? Why there?

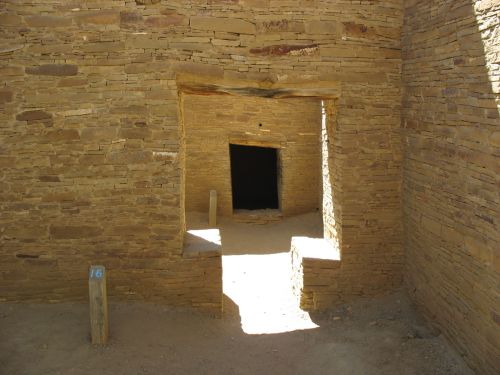

Room 170 at source: this Gamblers House post

One of the most important conclusions that leaps out of this book is that most of the societies examined had attitudes toward nature that were fairly compatible with a responsible, sustainable relationship with the environment, but that nearly all of them ended up destroying their environment anyway, either because they lacked the scientific and technological knowledge to know how to act best or because they let their values change as they became wealthier and more powerful through exploitation of natural resources.

from this post.

Sometimes you start looking for something, more information, help, and you find exactly what you’re looking for. You find a guide who can give you exactly the information you’re looking for, in a digestible way.

That’s what I found when I found The Gambler’s House. A dense, rich blog about Chaco by a former Park Service seasonal guide, he / she seems to know this stuff at a deep level. Here are two of the closest I find to autobiography.

source: Gambler’s House

The author, who signs the name Teofilio, writes with clarity, patience, intelligence, respect for the reader, restrained but confident style, and a steady, calm voice, walking us through questions, debates, and controversies within the scholarship:

So if great houses weren’t pueblos, what were they? Here’s where contemporary archaeologists tend to break into two main camps. One sees them as elite residences, part of some sort of hierarchical system centered on the canyon or, alternatively, of a decentralized system of “peer-polities” with local elites who emulated the central canyon elites in the biggest great houses. In either case, note that the great houses are still presumed to have been primarily residential. The difference from the traditional view is quantitative, rather than qualitative. These researchers see the lack of evidence for residential use in most rooms, but they also see that there is still some evidence for residential use, and they emphasize that and interpret the other rooms as evidence of the power and wealth of the few people who lived in these huge buildings and were able to amass large food surpluses or trade goods (or whatever). The specific models vary, but the core thing about them is that they see the great houses as houses, not for the community as a whole (most people lived in the surrounding “small houses” both inside and outside of the canyon) but for a lucky few.

In this camp are Steve Lekson, Steve Plog, John Kantner, probably Ruth Van Dyke (although she doesn’t talk about the specific functions of great houses much), and others.

On the other side are those who see the difference between pueblos and great houses as qualitative. To these people, the great houses were not primarily residential in function, although they may have housed some people from time to time. Most of these researchers see the primary function of the sites as being “ritual” in some sense, although what that means is not always clearly specified. In many cases a focus on pilgrimage (based on questionable evidence) is posited. This group tends to make a big deal out of the astronomical alignments and large-scale planning evident in the layouts and positions of the great houses within their communities. They tend to see the few residents of the sites as caretakers, priests, or other individuals whose functions allowed them to reside in these buildings. Importantly, they don’t see these sites as equivalent to other residences in any meaningful way. They are instead public architecture, perhaps built by egalitarian communities as an act of religious devotion. Examples of monumental architecture built by such societies are known throughout the world (Stonehenge is a famous example), and this view fits with the traditional interpretation of modern Pueblo ethnography, which sees the Pueblos as peaceful, egalitarian, communal villagers. There is a long tradition of projecting this image back into the prehistoric past based on the obvious continuities in material culture, so while these scholars are in some ways breaking with tradition in not seeing great houses as residential, they are also staying true to tradition in other ways by interpreting them as a past manifestation of cultural tendencies still known in the descendant societies but expressed in different ways.

(from this post).

While many archaeologists have made valiant attempts to fit the rise of Chaco into models based on local and/or regional environmental conditions, they have been generally unsuccessful in finding a model that convincingly explains the astonishing florescence of the Chaco system in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries. This has inspired some other archaeologists more recently to try a different tack involving less environmental determinism and more historical contingency. This seems promising, but finding sufficient evidence for this sort of approach is difficult when it comes to prehistoric societies like Chaco. The various camps of archaeologists will likely continue to argue about the nature of Chaco for a long time, I think. Meanwhile, the mystery remains.

from the post “Plaster“

I doubt this mystery will ever be totally solved. There’s just too much information that is no longer available for various reasons. That’s not necessarily a problem, though. At this point the mysteries of Chaco are among its most noteworthy characteristics. Sometimes not knowing everything, and accepting that lack of knowledge, is useful in coming to terms with something as impressive, even overwhelming, as Chaco. One way to deal with it all is to stop trying to figure out every detail and to just observe. The experience that results from this approach may have nothing to do with the original intent of the builders of the great houses of Chaco, but then again it may have everything to do with that intent. There’s no way to be sure, and there likely never will be. But that’s okay. Sometimes mysteries are better left unsolved.

What of the Gambler legend for the origin of Chaco? Alexandria Witze at Archaeology Conservancy tells us:

Navajo oral histories tell of a Great Gambler who had a profound effect on Chaco Canyon, the Ancestral Puebloan capital located in what is now northwestern New Mexico. His name was Nááhwiilbiihi (“winner of people”) or Noqóilpi (“he who wins men at play”), and he travelled to Chaco from the south. Once there, he began gambling with the locals, engaging in games such as dice and footraces. He always won.

Faced with such a formidable opponent, the people of Chaco lost all their possessions at first. Then they gambled their spouses and children and, finally, themselves, into his debt. With a group of slaves now available to do his bidding, the Gambler ordered them to construct a series of great houses—the monumental architecture that fills Chaco Canyon today.

when I picture The Gambler

What was up with Chaco Canyon’s roads? They were thirty feet wide, perfectly straight, and seem to go… nowhere?

Once you’re into Chaco Canyon before you know it you’re into Hovenweep.

and where does Mesa Verde fit into this?

So what was the relationship between the two? The short answer is that no one knows.

source: rationalobserver for wikipedia

This is a great post with a possible Chaco theory:

Briefly, what I’m proposing is that the rise of Chaco as a regional center could have been due to it being the first place in the Southwest to develop detailed, precise knowledge of the movements of heavenly bodies (especially the sun and moon), which allowed Chacoan religious leaders to develop an elaborate ceremonial calendar with rituals that proved attractive enough to other groups in the region to give the canyon immense religious prestige. This would have drawn many people from the surrounding area to Chaco, either on short-term pilgrimages or permanently, which in turn would have given Chacoan political elites (who may or may not have been the same people as the religious leaders) the economic base to project political and/or military power throughout a large area, and cultural influence even further.

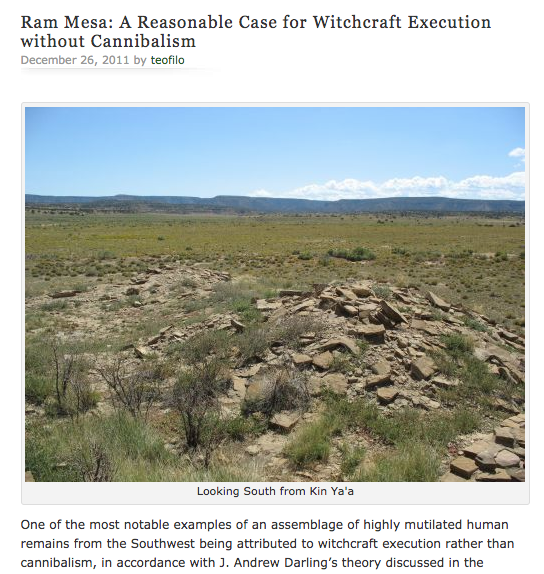

The “sexiest” post title:

Hovenweep

Posted: November 28, 2018 Filed under: America, desert, Indians, joshua tree, native america Leave a commentWhat a name for a place.

between 1150-1350 these structures were built in, around, and above this canyon:

Gotta check that out sometime:

Was this era in the American Southwest something like roughly the same period, the early 12th century in Ireland:

To be glib, early medieval Ireland sounds like a somewhat crazed Wisconsin, in which every dairy farm is an armed at perpetual war with its neighbors, and every farmer claims he is a king.

Or was Hovenweep perhaps something more like a monastery?

Some Anasazi taking the Benedict Option?

Thought this was a good trip report from Hovenweep.

Got to Hovenweep trying to read about traditional architecture in the American desert regions. What kinds of buildings have people with few tools and tech built? What lasts?

This guy took on the challenge of building a pit house and kiva.

Easier than a kiva would be a false kiva:

John Fowler for wikipedia

Hidden Springs of Crazy Horse-iana

Posted: October 7, 2018 Filed under: history, native america 4 Comments

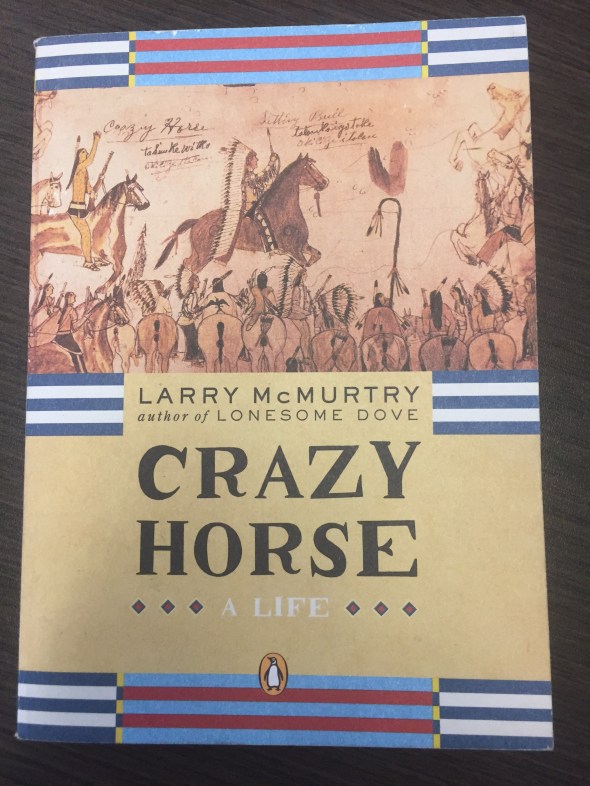

Reread Larry McMurtry’s short life of Crazy Horse.

Discovered something new: when No Water shot Crazy Horse for running away with his wife Black Buffalo Woman, he borrowed the gun he used from Bad Heart Bull.

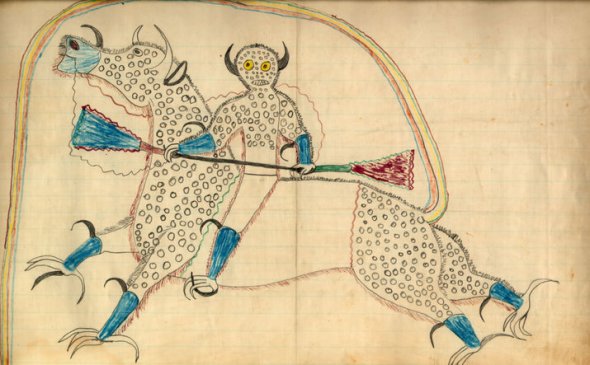

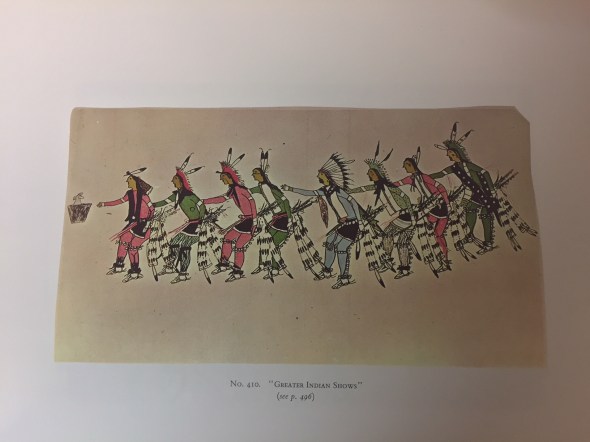

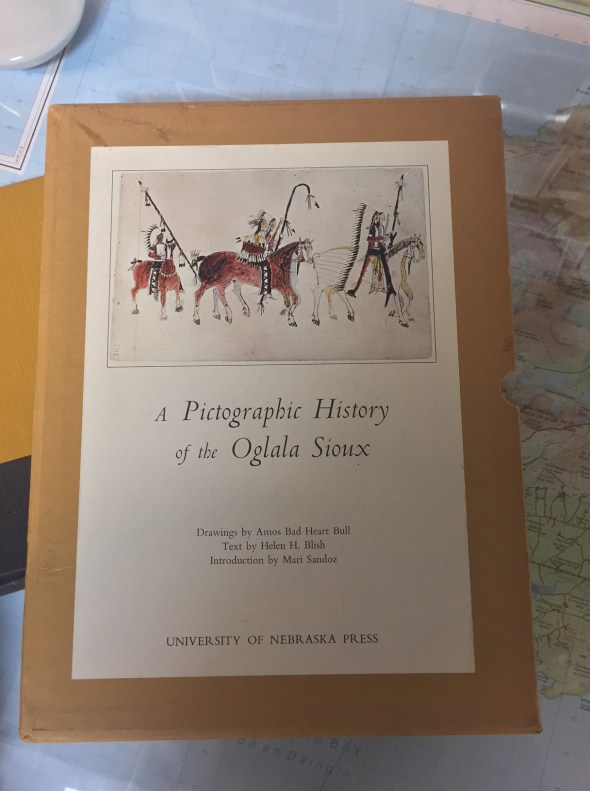

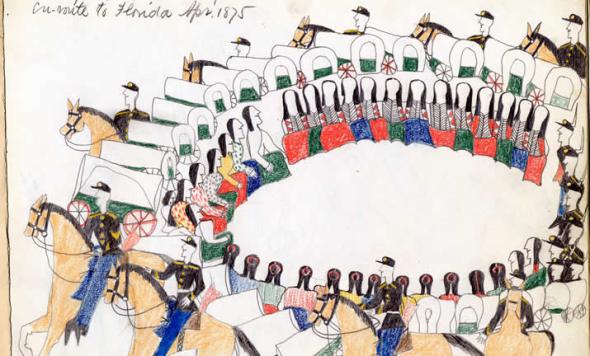

This Bad Heart Bull was an uncle of Amos Bad Heart Bull, the ledger artist, who made this drawing of the death of Crazy Horse:

At the time of his death, Amos’ sketchbook was given to his younger sister, Dolly Pretty Cloud. In the 1930s, she was contacted by Helen Blish, a graduate student from the University of Nebraska, who asked to study her brother’s work for her master’s thesis in art. When Pretty Cloud died in 1947, her brother’s ledger book full of drawings was buried with her.

Before they were buried, the drawings were photographed by Blish’s professor, Hartley Burr Alexander, and they’re reprinted in this volume:

Amos Bad Heart Bull was only one of the Ledger Artists.

Much Ledger Art can be seen digitally through the Plains Ledger Art Project at UC San Diego.

Amos Bad Heart Bull’s work is vivid:

A literal translation of the Lakota word čhaŋtéšiče is “he has a bad heart”, but an idiomatic meaning is “he is sad.” Tȟatȟáŋka Čhaŋtéšiče would likely have been understood in the same way “Sad Bull” would be in English. When Lakota names are translated literally into English, they may lose their idiomatic sense.

Crazy Horse, Little Bighorn, these names alone are compelling enough. Cavalrymen wiped out to the last man on the plains, these stories are interesting, or they have been to me as long as I remember.

This book couldn’t’ve been more what I wanted. I first discovered it when TV commercials for the miniseries aired.

In my opinion the miniseries is damn good, but the book! Part of what makes it so compelling is Connell sees how the telling of what happened, the attempt to figure out what happened, is as interesting as what happened itself. The history of the history is as interesting as the history.

Connell starts his book with the troopers who discovered the stripped and mutilated bodies on the hillside, then takes us on a digressive journey towards how this happened, what happened, and what it all might mean, if anything.

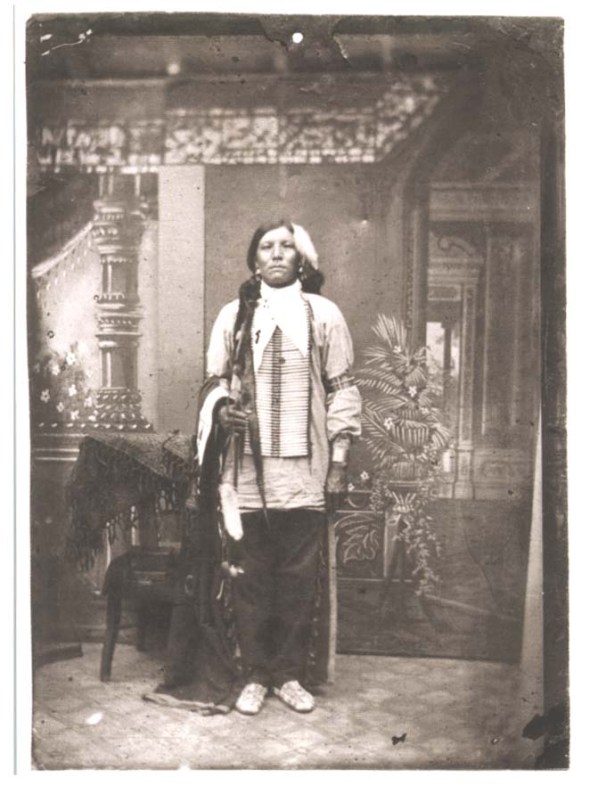

Wikipedia presents this disputed picture of Crazy Horse. It cannot be him. He would never. At Fort Robinson?? A desolate prairie outpost? This was taken in a city. Etc. From what we know of Crazy Horse, this is the opposite of what he would do.

But who knows? Who is it? Ghosts appear and disappear.

Crazy Horse had a daughter named They Are Afraid of Her. She died, probably of cholera, McMurtry says, when she was three.

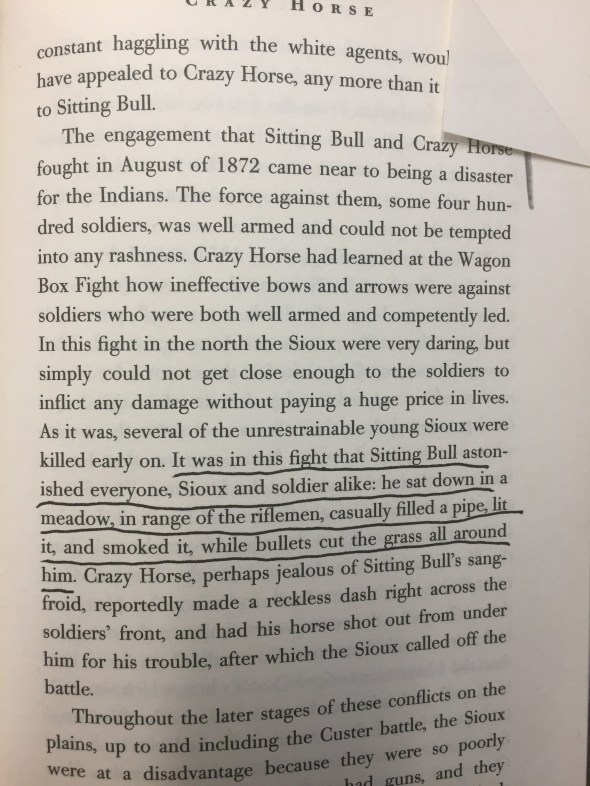

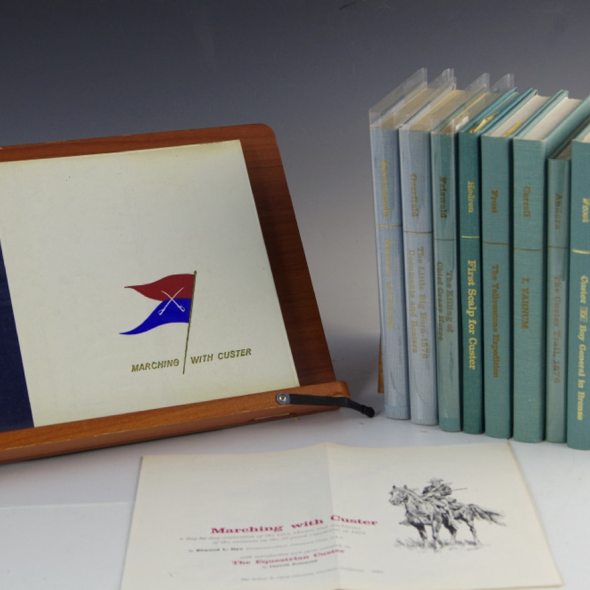

How about the legend of what happened at the Baker Fight:

In the middle of a frantic battle a man sits on the grass and smokes a pipe.

This occurred during what is sometimes called the Arrow Creek Fight, or the Baker Fight.

found that here.

Once spent some time on Google Maps trying to find the site of the Baker fight.

While reading about one of the few white men Crazy Horse trusted, Doctor Valentine McGillycuddy:

I find a reference to a thirteen volume set, Hidden Springs of Custeriana.

The hunt for hidden springs in the long pored-over records of the past. The ledger photographed, then buried in Nebraska.

more:

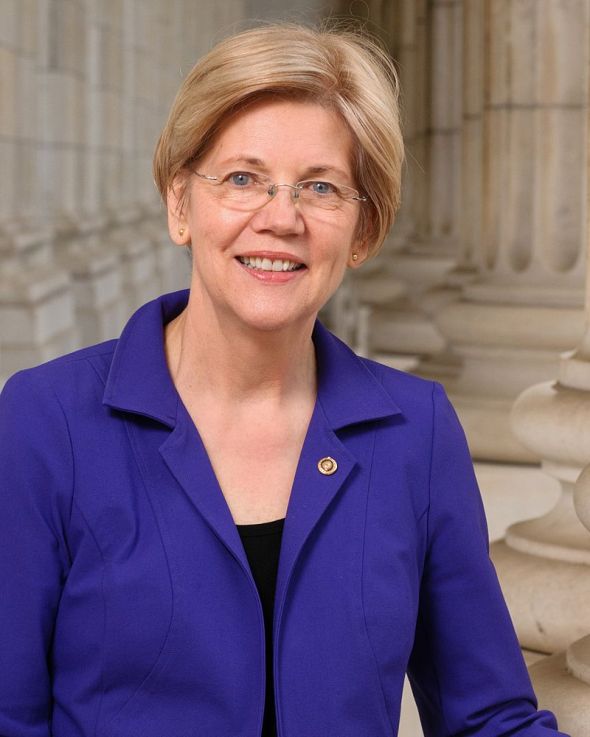

Elizabeth Warren, Pocahontas, and The Pow Wow Chow Cookbook

Posted: December 14, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, Boston, native america, New England, politics, presidents 1 Comment

What is the deal here when Trump calls Elizabeth Warren Pocahontas?

At Helytimes, we like to go back to the source.

Sometime between 1987 and 1992 Elizabeth Warren put down on a faculty directory that she was Native American. Says Snopes:

it is true that while Warren was at U. Penn. Law School she put herself on the “Minority Law Teacher” list as Native American) in the faculty directory of the Association of American Law Schools

This became a story in 2012, when Elizabeth Warren was running for Senate against Scott Brown. In late April of that year, The Boston Herald, a NY Post style tabloid, dug up a 1996 article in the Harvard Crimson by Theresa J. Chung that says this:

Of 71 current Law School professors and assistant professors, 11 are women, five are black, one is Native American and one is Hispanic, said Mike Chmura, spokesperson for the Law School.

Although the conventional wisdom among students and faculty is that the Law School faculty includes no minority women, Chmura said Professor of Law Elizabeth Warren is Native American.

Asked about it, here’s what Elizabeth Warren said:

From there the story kinda spun out of control. It came up in the Senate debate, and there were ads about it on both sides.

A genealogist looked into it, and determined that Warren was 1/32nd Cherokee, or about as Cherokee as Helytimes is West African. But then even that was disputed.

Her inability to name any specific Native American ancestor has kept the story alive, though, as pundits left and right have argued the case. Supporters touted her as part Cherokee after genealogist Christopher Child of the New England Historic Genealogical Society said he’d found a marriage certificate that described her great-great-great-grandmother, who was born in the late 18th century, as a Cherokee. But that story fell apart once people looked at it more closely. The Society, it turned out, was referencing a quote by an amateur genealogist in the March 2006 Buracker & Boraker Family History Research Newsletters about an application for a marriage certificate.

Well, Elizabeth Warren won. Now Scott Brown is Donald Trump’s Ambassador to New Zealand, where he’s doing an amazing job.

source: The Guardian

The part of the story that lit me up was this:

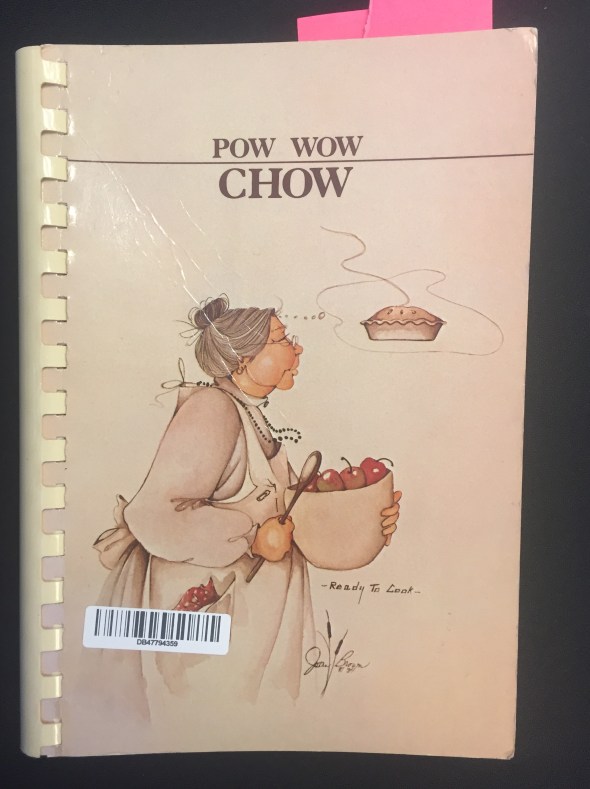

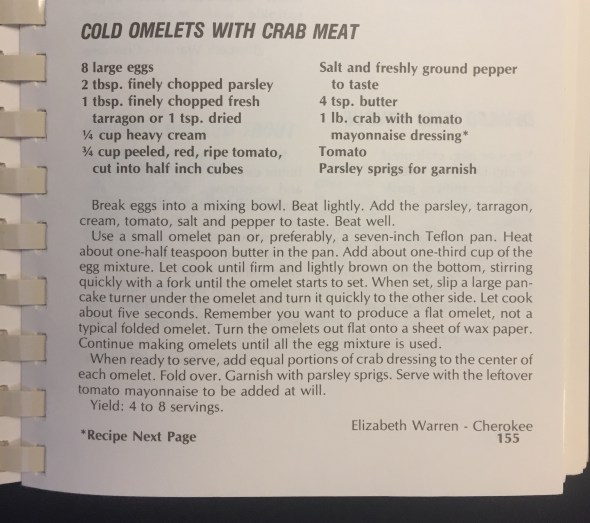

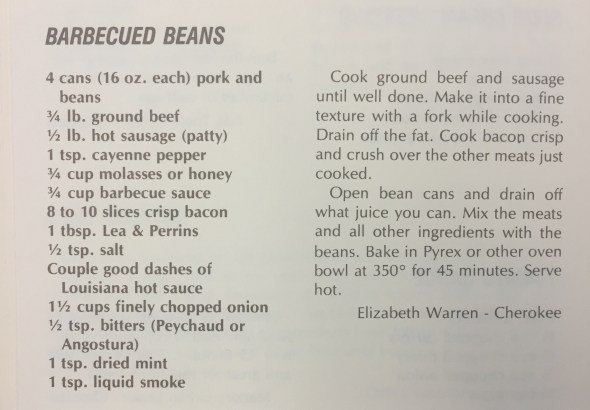

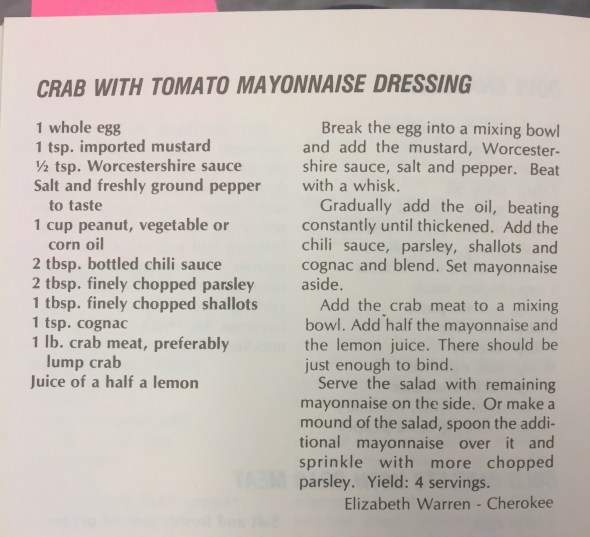

The best argument she’s got in her defense is that, based on the public evidence so far, she doesn’t appear to have used her claim of Native American ancestry to gain access to anything much more significant than a cookbook; in 1984 she contributed five recipes to the Pow Wow Chow cookbook published by the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, signing the items, “Elizabeth Warren — Cherokee.”

“I like my corn with olives!” source

What is the best way to handle it, the best strategy, when the President is treating you like a third grade bully, repeatedly and publicly calling you a mean name?

Best advice to someone getting bullied? I googled:

We would amend “don’t show your feelings” to stay calm. We would urge any kid to put “tell an adult” as a last resort.

A suggestion:

- if the problem persists, hit back as hard as possible, calmly but forcefully, at the bully’s weakest, tenderest points.

Such a Lisa Simpson / Nelson vibe to Warren / Trump. Are all our elections gonna be Lisa vs. Nelson for awhile?

from this 2003 episode:

Lisa easily wins the election. Worried by her determination and popularity, the faculty discusses how to control her.

Score.

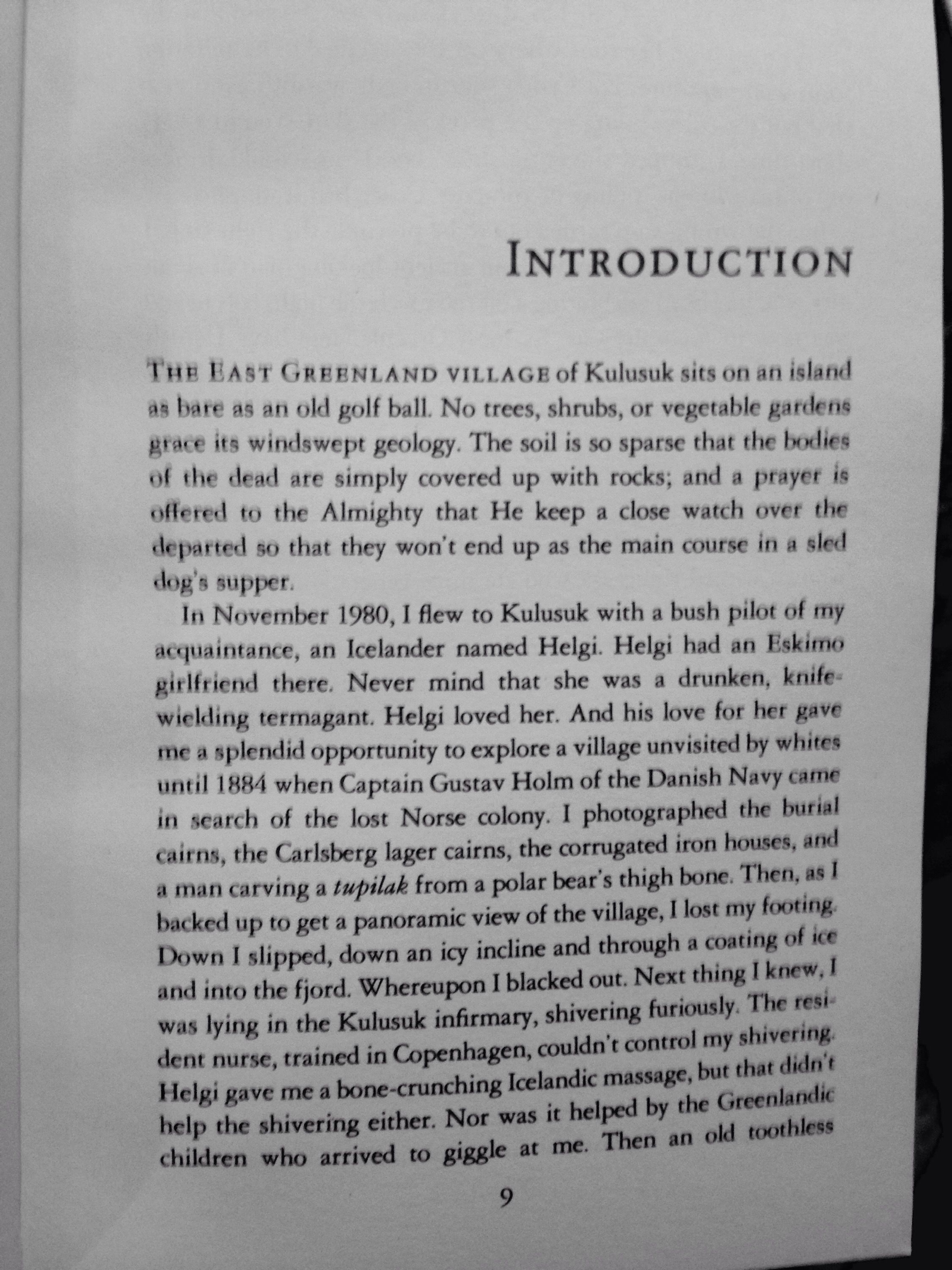

Posted: January 14, 2015 Filed under: Canada, native america, writing Leave a commentSweet! A package arrived!

Let’s see what I got…

Oh, it’s Kayak Full Of Ghosts: Eskimo Tales, gathered and retold by Lawrence Millman. Let’s hear what Millman is up to:

You know what, let’s just jump right in and read one of the stories:

Ok…

Well, lots to think about. Thanks to Dan Vebber for putting me on to Millman.

Imagine you’re exploring around the Pacific Northwest in 1800

Posted: July 10, 2013 Filed under: America, native america 2 Commentsand you see this:

Pretty scary. That’s from this book: