Professor Longhair

Posted: March 4, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, music, New Orleans Leave a commentMardi Gras has me thinking about Professor Longhair. In his memoir Rhythm and Blues Jerry Wexler tells a story about Ahmet Ertegun finding the Professor:

I’d started noticing Atlantic’s early releases with Professor Long-hair’s “Hey Now Baby,” “Hey Little Girl,” and “Mardi Gras in New Orleans.” Fess—as the Professor was called—was a revelation for me, my first taste of the music being served up in Louisiana in the late forties.

There were traces of Jelly Roll Morton’s habanera-Cuban tango influence in his piano style, but the overall effect was startlingly original, a jambalaya Caribbean Creole rumba with a solid blues bottom.

In a foreshadowing of trips I myself would later take to New Orleans, Ahmet described the first of his many ethnomusicological expeditions. “Herb and I went down there to see our distributor and look for talent. Someone mentioned Professor Longhair, a musical shaman who played in a style all his own. We asked around and finally found ourselves taking a ferry boat to the other side of the Mississippi, to Algiers, where a white taxi driver would deliver us only as far as an open field. ‘You’re on your own,’ he said, pointing to the lights of a distant village. ‘I ain’t going into that n***ertown.’ Abandoned, we trudged across the field, lit only by the light of a crescent moon. The closer we came, the more distinct the sound of distant music—some big rocking band, the rhythm exciting us and pushing us on. Finally we came upon a nightclub—or, rather, a shack—which, like an animated cartoon, appeared to be expanding and deflating with the pulsation of the beat. The man at the door was skeptical. What did these two white men want? ‘We’re from Life magazine,’ I lied.

Inside, people scattered, thinking we were police. And instead of a full band, I saw only a single musician—Professor Longhair—playing these weird, wide harmonies, using the piano as both keyboard and bass drum, pounding a kick plate to keep time and singing in the open-throated style of the blues shouters of old. “ ‘My God,’ I said to Herb, ‘we’ve discovered a primitive genius.’ “Afterwards, I introduced myself. ‘You won’t believe this,’ I said to the Professor, ‘but I want to record you.’ “ ‘You won’t believe this,’ he answered, ‘but I just signed with Mercury.’

Ahmet recorded him anyway—“ I am many men with many names who play under many styles,” Fess used to say—and jewels from that first session remain in the Atlantic catalogue today, over four decades later.”

(source on that photo) Previous coverage of New Orleans.

Lincoln in New Orleans (featuring final answer on was Abraham Lincoln gay?)

Posted: January 18, 2025 Filed under: Mississippi, New Orleans, presidents Leave a comment

In the year 1828 nineteen year old Abraham Lincoln went on a flatboat trip with a local twenty one year old named Allen Gentry. He would be paid eight dollars a month plus steamboat fare home. They left from Spencer County, Indiana, down the Ohio to the Mississippi.

The great New Orleans geographer and historian Richard Campanella wrote a whole book, Lincoln In New Orleans, about Lincoln’s experience on this trip and another down in New Orleans. It’s a really illuminating work on Lincoln, the Mississippi River at that time, the floatboatman life, early New Orleans.

If you need step by step instructions on building a flatboat, they’re in Campanella’s book. (People back then worked so hard!)

Campanella tells us in vivid reconstruction from various sources what this trip must’ve been like:

the Mississippi River in its deltaic plain no longer collected water through tributaries but shed it, through distributaries such as bayous Manchac, Plaquemine, and Lafourche (“the fork”). This was Louisiana’s legendary

“sugar coast,” home to plantation after plantation after plantation, with their manor houses fronting the river and dependencies, slave cabins, and

“long lots” of sugar cane stretching toward the backswamp. The sugar coast claimed many of the nation’s wealthiest planters, and the region had one of the highest concentrations of slaves (if not the highest) in North America. To visitors arriving from upriver, Louisiana seemed more Afro-Caribbean than American, more French than English, more Catholic than Protestant, more tropical than temperate. It certainly grew more sugar cane than cotton (or corn or tobacco or anything else, probably combined).

To an upcountry newcomer, the region felt exotic; its society came across as foreign and unknowable. The sense of mystery bred anticipation for the urban culmination that lay ahead.

What Lincoln did in New Orleans is recorded only in a few stray remarks from the man himself and secondhand stories remembered afterwards by those he told them to, who then told them to William Herndon, biographer and law partner of Lincoln. (now they can be found in a volume called Herndon’s Informants). What was Lincoln like in New Orleans?

Observing the behavior of young men today, sauntering in the French Quarter while on leave from service, ship, school, or business, offers an idea of how flatboatmen acted upon the stage of street life in the circa-1828 city. We can imagine Gentry and Lincoln, twenty and nineteen years old respectively, donning new clothes and a shoulder bag, looking about, inquiring what the other wanted to do and secretly hoping it would align with his own wishes, then shrugging and ambling on in a mutually consensual direction. Lincoln would have attracted extra attention for his striking physiognomy, his bandaged head wound from the attack on the sugar coast, and his six-foot-four height, which towered ten inches over the typical American male of that era and even higher above the many New Orleanians of Mediterranean or Latin descent.

Quite the conspicuous bumpkins were they.

One cannot help pondering how teen-aged Lincoln might have behaved in New Orleans. Young single men like him (not to mention older married men) had given this city a notorious reputation throughout the Western world; condemnations of the city’s wickedness abound in nineteenth-century literature. A visitor in 1823 wrote,

New Orleans is of course exposed to greater varieties of human misery, vice, disease, and want, than any other American town. … Much has been said about [its] profligacy of manners, morals… debauchery, and low vice … [T]his place has more than once been called the modern Sodom.

Campanella considers what we know about Lincoln and women:

I consider the matter concluded that Abe was a gentle shyguy ladykiller.

I found this passage very real:

Campanella gives us the political context of the time:

There was much to editorialize about in the spring of 1828. A concurrence of events made politics particularly polemical that season. Just weeks earlier, Denis Prieur defeated Anathole Peychaud in the New Or-leans mayoral race, while ten council seats went before voters. They competed for attention with the U.S. presidential campaign— a mudslinging rematch of the bitterly controversial 1824 election, in which Westerner Andrew Jackson won a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote in a four-candidate, one-party field, but John Quincy Adams attained the presidency after Congress handed down the final selection. Subsequent years saw the emergence of a more manageable two-party system. In 1828, Jackson headed the Democratic Party ticket while Adams represented the National Republican Party (forerunner of the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party). Jackson’s heroic defeat of the British at New Orleans in 1815 had made him a national hero with much local support, but did not spare him vociferous enemies. The year 1828 also saw the state’s first election in which presidential electors were selected by voters-white males, that is—rather than by the legislature, thus ratcheting up public interest in the contest. 238 Every day in the spring of 1828 the local press featured obsequious encomiums, sarcastic diatribes, vicious rumors, or scandalous allegations spanning multiple columns. The most infamous-the “coffin hand bills,” which accused Andrew Jackson of murdering several militiamen executed under his command during the war—-circulated throughout the city within days of Lincoln’s visit. 23% New Orleans in the red-hot political year of 1828 might well have given Abraham Lincoln his first massive daily dosage of passionate political opinion, via newspapers, broadsides, bills, orations, and overheard conversations.

Before they got to New Orleans, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked by a group of seven Negroes, possibly runaway slaves? Little is known for sure about the incident, except that they messed with the wrong railsplitter. Lincoln was famously strong and a good fighter:

In a remarkable bit of historical detective work, Campanella concludes that a woman sometimes called “Bushan” may have been Dufresne, and puts together this incredible map:

Really impressed with Campanella’s work, I also have his book Bienville’s Dilemma, and add him to my esteemed Guides to New Orleans. Campanella goes into some detail about how and in what forms Lincoln would’ve encountered slavery on this trip. Any dramatic statement about it he made during the trip though seems historically questionable. When Lincoln talked about this trip in political speeches, he used it as an example of how he’d once been a working man. For example, 1860 in New Haven:

Free society is such that a poor man knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition-when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him!’

Campanella does cite a letter Lincoln wrote in 1860 where he did speak on what he saw of slavery:

Making a flatboat trip was a rite of passage for a young buck of the Midwest at that time. Whether it brought Lincoln to full maturity is discussed in a poignant and comic anecdote:

An awkward incident one year after the New Orleans trip yanked the maturing but not yet fully mature Abraham back into the petty world of past grievances. How he dealt with it reflected his growing sophistication as well as his lingering adolescence. Two Grigsby brothers— kin of Aaron, the former brother-in-law whom Abraham resented for not having done enough to aid his ailing sister Sarah Lincoln-married their fiancées on the same day and celebrated with a joint “infare.” The Grigsbys pointedly did not invite Lincoln. In a mischievous mood, Abraham exacted revenge by penning a ribald satire entitled “The Chronicles of Reuben,” in which the two grooms accidentally end up in bed together rather than with their respective brides. Other locals suffered their own indignities within the stinging verses of Abraham’s poem, nearly resulting in fisticuffs. The incident botses tected and exacerbated Lincoln’s growing rift with all things related to Spencer County.

An article version of Campanella’s book is available free.

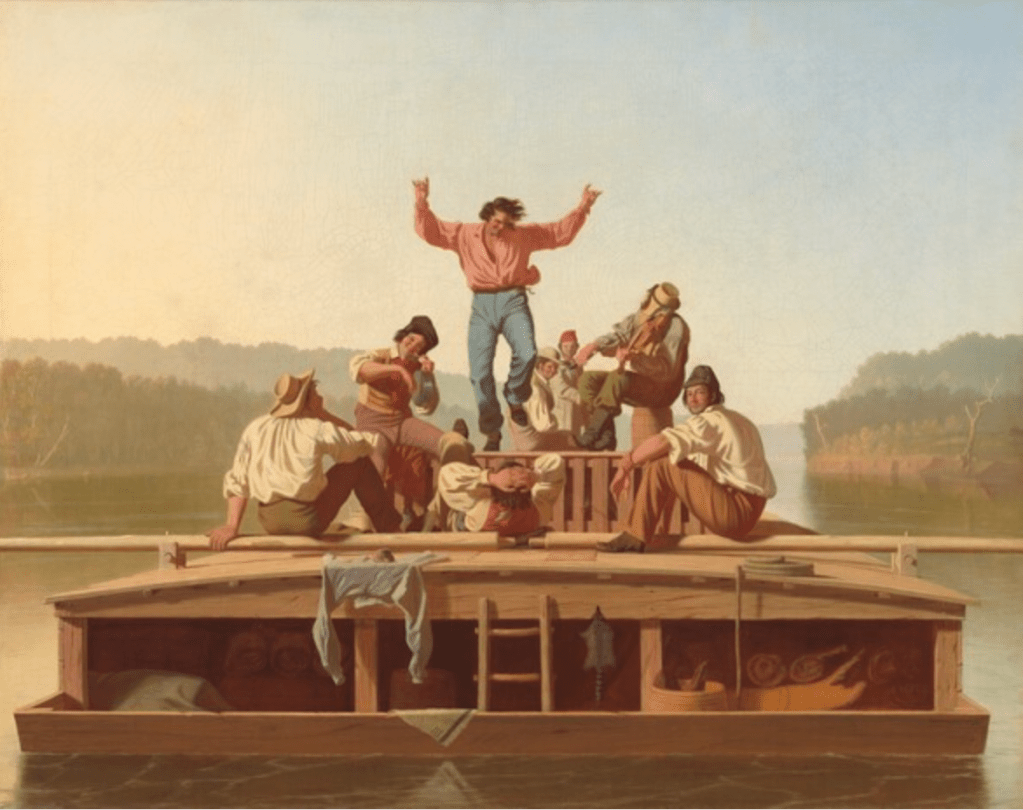

That painting is of course Jolly Flatboatmen, which we discussed back in 2012.

WWOZ

Posted: February 28, 2022 Filed under: Louisiana, New Orleans Leave a commentHomebound at the opening stages of the pandemic (around the time of the “Tom Hanks Crisis”) we started listening, via Internet stream, to WWOZ, roots radio from New Orleans. The music is festive, the catalog is deep: it’s kind of amazing how much music there is about New Orleans. WWOZ could fill days and days with specifically local music.

Metro New Orleans has 1.2 million people, putting it below Oklahoma City, Pittsburgh, greater Orlando, Sacramento, just a hair above Fresno in terms of size. But New Orleans punches so far above its weight culturally as to make it a unique exception and special case on a world scale.

Something about listening to an actual radio station with live DJs feels more connective, although Bryson Whitney at Spotify keeps a WWOZ playlist that has way beyond 24 hours of music at the ready.

WWOZ is the station where Steve Zahn’s character, Davis McAlary, is a DJ in the 2010-2013 HBO series Treme*, but don’t let that put you off. The DJs for the most part are remarkably unobtrusive.

Tuesday is Mardi Gras. There are enough songs specifically about Mardi Gras to power WWOZ for probably weeks of steady airtime. You will hear Professor Longhair and Wild Tchoupitoulas. It’s funny to observe the transition in music when Ash Wednesday rolls around. They really do have to dial it back!

Previous coverage of New Orleans.

* when Treme first came out we found it a little offputting, it seemed to be criticizing us, the viewers, for not appreciating New Orleans enough. This may have been partially based on a scene in the pilot where some well-meaning tourists are humiliated by Sonny (Michiel Huisman), a street musician. But we rewatched a few years ago and found the series went deeper than we may have perceived. For instance Sonny himself is a transplant. His pretentious attitude is deflated over the course of the series as he experiences a humbling journey related to his efforts to get out of addiction and restore himself. On review ,Treme does a powerful job of capturing not only what’s so special and alluring about New Orleans, but also what’s probably annoying and frustrating about living there. The dilapidations, corruptions, poverty and inevitable hangovers of a place that survives by selling itself as partytown. Some of New Orleans is disgusting, some of it is really refined and beautiful. Those contradictions are captured in the show, full of inhabited characters who aren’t always having good times. Treme is deep and interesting if not always fun.

Tchoupitoulas

Posted: June 21, 2019 Filed under: food, music, New Orleans Leave a comment

po’boys at Domilie’s

There are many famous and intriguing streets in New Orleans – Royal, Esplanade, Canal, Basin, Magazine, St. Claude Avenue, St. Charles Avenue, Chartres – but a street that caught my interest is Tchoupitoulas.

Traveled this street while on my way back from Domilise’s, which David Chang once claimed serves the coldest beer in the world.

Could be!

Tchoupitoulas runs alongside the Mississippi. There is an enormously long, apparently vacant structure that runs along the river and the railroad tracks.

I asked a bartender at Cavan in the Irish Channel about this structure. She told me it’s a set of wharves and warehouses, many of them still privately owned. It was said, according to her, that somewhere under this place Marie Laveau had once had her voodoo church.

based on a drawing, now lost, by George Catlin

“The Wild Tchoupitoulas” were a band of Mardi Gras Indians, who in 1976, with the help of the Neville Brothers and some members of The Meters, recorded an album based on their chants.

Viewers of Treme will recall that Steve Zahn’s character and his girlfriend Annie Tee have a discussion when they move in together about whether they need to keep both of their two CDs of The Wild Tchoupitoulas.

Next time I’m on Tchoupitoulas I’m going to visit Hansen’s Sno-Bliz.

Iko Iko and Mobilian Jargon

Posted: June 19, 2019 Filed under: language, Louisiana, music, New Orleans Leave a comment

Reading up on the New Orleans classic Iko Iko, made famous by the Dixie Cups, I find myself reading about Mobilian Jargon.

Mobilian Jargon (also Mobilian trade language, Mobilian Trade Jargon, Chickasaw–Choctaw trade language, Yamá) was a pidgin used as a lingua franca among Native American groups living along the Gulf of Mexico around the time of European settlement of the region. It was the main language among Indian tribes in this area, mainly Louisiana. There is evidence indicating its existence as early as the late 17th to early 18th century. The Indian groups that are said to have used it were the Alabama, Apalachee, Biloxi, Chacato, Pakana, Pascagoula, Taensa, Tunica, Caddo, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Chitimacha, Natchez, and Ofo.

A possible meaning?:

Another possible translation interprets the third and fourth lines as:[30]

Chokma finha an dan déyè

Chokma finha ane.Chickasaw words “chokma” (“it’s good”) and “finha” (“very”), Creole “an dan déyè” from French Creole “an dans déyè” (“at the back”), and the Creole “ane” from the French “année” (“year”).

Translation:

It’s very good at the rear

It’s a very good year.

What about the possible voodoo origin?

Louisiana Voodoo practitioners would recognize many aspects of the song as being about spirit possession. The practitioner, the horse, waves a flag representing a certain god to call that god into himself or herself. Setting a flag on fire is a curse. The man in green, who either changes personality or whose appearance is deceiving, would be recognized in Voodoo as possessed by a peaceful Rada spirit, inclining to green clothes and love magic. The man in red, who is being sent to kill, would likely be possessed by a vengeful Petwo spirit.[33]

Haitian ethnologist Milo Rigaud published a transcription in 1953 of a Voodoo chant, “Crabigne Nago”[34]. This chant to invoke the Voodoo mystère Ogou Shalodeh is similar to “Iko, Iko” in both pentameter and phones.

Liki, liki ô! Liki, liki ô!

Ogou Shalodeh.

Papa Ogou Jacoumon,

Papa Ogou Shalodeh.

More on the topic can be found in an article in a 2008 issue of Southern Anthropologist – we find ourselves amidst controversy:

Right from the beginning, Galloway (2006: 225-226) belittles the amount of linguistic information available, which she evidently takes as a justifi cation for not addressing specifi c linguistic and historical data that Crawford and I have accumulated and analyzed over the years. Although Galloway (2006: 228) recognizes my book of some four hundred pages as “the most thorough study of Mobilian jargon (sic) now available,” she oddly does not use a single piece of linguistic data from it in her own essay; nor does she review the substantial amount of sociohistorical documentation that both Crawford and I assembled for what anthropologists and linguists had long thought lost. Instead, Galloway (2006: 240) has curiously drawn on a short, seven-page essay by Kennith H. York (1982) for inspiration and “the insight of a sophisticated native speaker of Choctaw,” which demands a short appraisal

The linguistic origin of the song is the subject of a 2009 Offbeat article by Drew Hinshaw, who traces it to Ghana:

One afternoon, 1965, the three Louisianan sisters/cousins who gave you “Chapel of Love,” unaware that the studio’s tapes were still rolling, recorded for posterity two minutes of delightful historical intrigue that had been circulating in oral obscurity for generations unknowable. “Iko, Iko,” they called that tune. The English chunks of the record came from an all-too-obvious source—R&B singer “Sugar Boy” Crawford who claimed he never saw “just dues” from the top 40 hit—but the cryptic refrain of the Carnival standard is of a lost language, entirely mysterious: “Eh na, Iko, Iko-ahn-dé, jaco-mo-fi-na-né.” You know these words. “Sugar Boy” said he remembered them from the Mardi Gras Indian tribes of his salad days, while the girl group said they heard it from their grandma, Which is where the song begins: “My grandmaw and yo’ grandmaw….”

Reminded me of this cool, dialogue-less scene in Twelve Years A Slave which probably tells us about as much as can be known about the earliest origins of New Orleans music:

Not sure why I bothered writing this post, as I already texted with MMW about this topic (he suggested I look into Pidgin Delaware) but the oddest topics have lured readers to Helytimes, and really, what else is this site for but

1) to peer into the past until the view becomes a crazy fantastical kaleidoscope

2) to celebrate the rich weirdness of the world, and

3) to delight that there are people out there fighting over Mobilian Jargon?