Steinbeck on the two Christmases

Posted: December 22, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, Steinbeck, the California Condition Leave a commentWriting about the quiz show scandal in The Fifties, David Halberstam says:

It was a traumatic moment for the country as well. Charles Van Doren had become the symbol of the best America had to offer. Some commentators wrote of the quiz shows as the end of American innocence. Starting with World War Two, they said, America had been on the right side: Its politicians and generals did not lie, and the Americans had trusted what was written in their newspapers and, later, broadcast over the airwaves. That it all ended abruptly because one unusually attractive young man was caught up in something seedy and outside his control was dubious. But some saw the beginning of the disintegration of the moral tissue of America, in all of this. Certainly, many Americans who would have rejected a role in being part of a rigged quiz show if the price was $64 would have had to think a long time if the price was $125,000. John Steinbeck was so outraged that he wrote an angry letter to Adlai Stevenson that was reprinted in The New Republic and caused a considerable stir at the time. Under the title “Have We Gone Soft?” he raged, “If I wanted to destroy a nation I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy, and sick … on all levels, American society is rigged…. I am troubled by the cynical immorality of my country. It cannot survive on this basis.”

This isn’t quite accurate, as far as I can tell – “Have We Gone Soft?” was an article by the Jesuit Thurston N. Davis, included as part of a larger symposium, in the February 15, 1960 New Republic, you can read it here. No matter.

Steinbeck’s phrase or the rough idea of it stuck with me since I read The Fifties back in high school (in Frank Guerra’s class, American Since ’45, the best class in my high school (we used to call it “Guerra Since ’45” since a lot of it was Coach Guerra’s personal memories of era, which were terrific and much appreciated, as Frank Guerra was one of the most charismatic teachers at the school and the head football coach. We’re straying)).

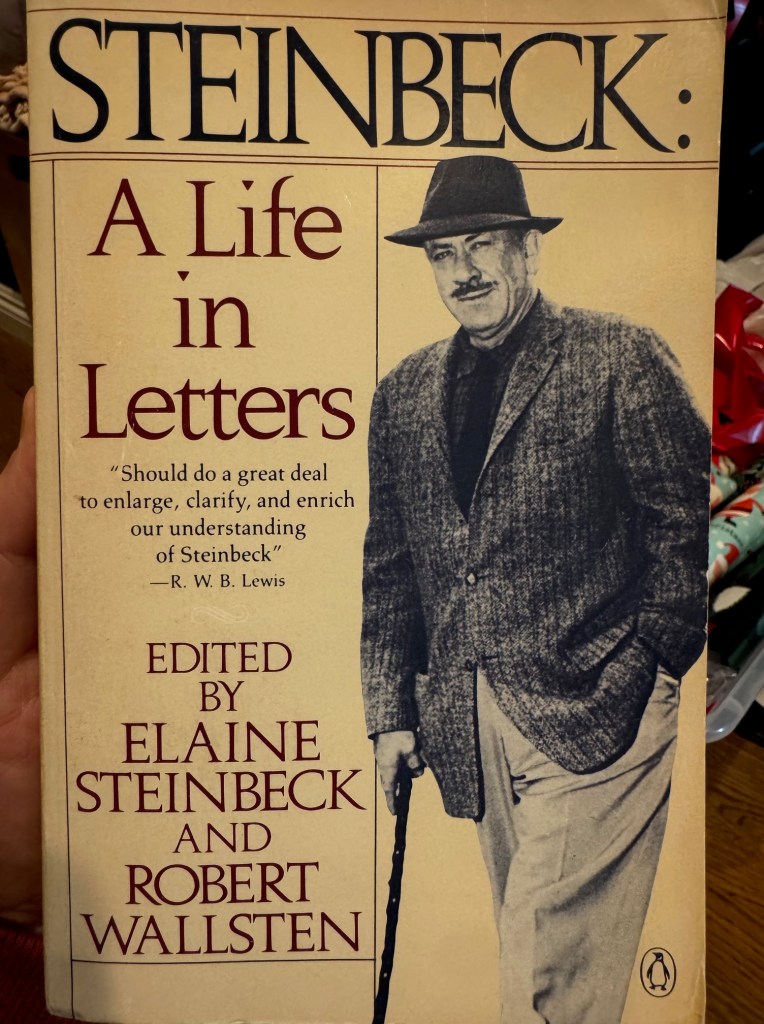

The other day I realized I had a copy of Steinbeck’s letters on my shelf. It might have the quoted letter in it.

On the cover Steinbeck looks kind of like a stodgy old GK Chesterton sort of guy:

but inside there’s a photo of him where he looks more like the louche California artist:

He looks kind of like the late Brian Reich. Those two poles of Steinbeck are there in the book.

Here’s a bit more of that quoted letter:

New York

[November 5] 1959

Guy Fawkes Day

Dear Adlai:

Back from Camelot, [I think Steinbeck is referring to literal Camelot here, like King Arthur country in the UK, Steinbeck was obsessed with King Arthur and he’d just gone there to research] and, reading the papers not at all sure it was wise. Two first impressions. First a creeping, all-per-vading, nerve-gas of immorality which starts in the nursery and does not stop before it reaches the highest offices, both corporate and governmental. Two, a nervous restlessness, a hunger, a thirst, a yearning for something unknown-per-haps morality. Then there’s the violence, cruelty and hypocrisy symptomatic of a people which has too much, and last the surly, ill-temper which only shows up in humans when they are frightened.

Adlai, do you remember two kinds of Christmases? There is one kind in a house where there is little and a present represents not only love but sacrifice. The one single package is opened with a kind of slow wonder, almost reverence.

Once I gave my youngest boy, who loves all living things, a dwarf, peach-faced parrot for Christmas. He removed the paper and then retreated a little shyly and looked at the little bird for a long time. And finally he said in a whisper, “Now who would have ever thought that I would have a peach-faced parrot?”

Then there is the other kind of Christmas with presents piled high, the gifts of guilty parents as bribes because they have nothing else to give. The wrappings are ripped off and the presents thrown down and at the end the child says-“Is that all?”

Well, it seems to me that America now is like that second kind of Christmas. Having too many THINGS they spend their hours and money on the couch searching for a soul. A strange species we are. We can stand anything God and Nature can throw at us save only plenty. If I wanted to destroy a nation, I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy and sick. And then I think of our “Daily” in Somerset, who served your lunch. She made a teddy bear with her own hands for our grandchild. Made it out of an old bath towel dyed brown and it is beautiful. She said, “Sometimes when I have a bit of rabbit fur, they come out lovelier.” Now there is a present. And that obviously male Teddy Bear is going to be called for all time MIZ Hicks.

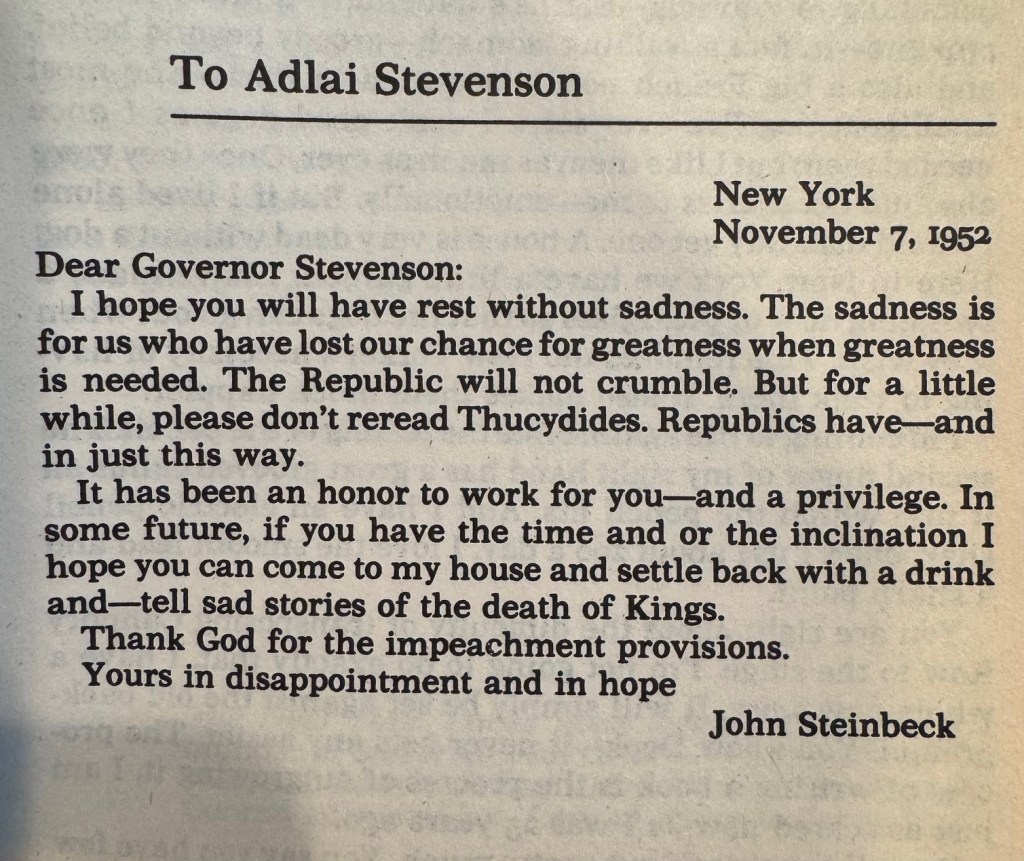

Kind of a conservative idea in a way. Yet Steinbeck is writing to Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic candidate for president. Steinbeck did some speechwriting for Adlai. When Adlai lost to Eisenhower in 1952, Steinbeck wrote him this one:

It seems a bit drastic in retrospect, Eisenhower is mostly regarded as a pretty good president, certainly by comparison, although he did overthrow a few foreign governments (see discussion of Guatemala in Hely’s The Wonder Trail.) But I guess they really felt this at the time.

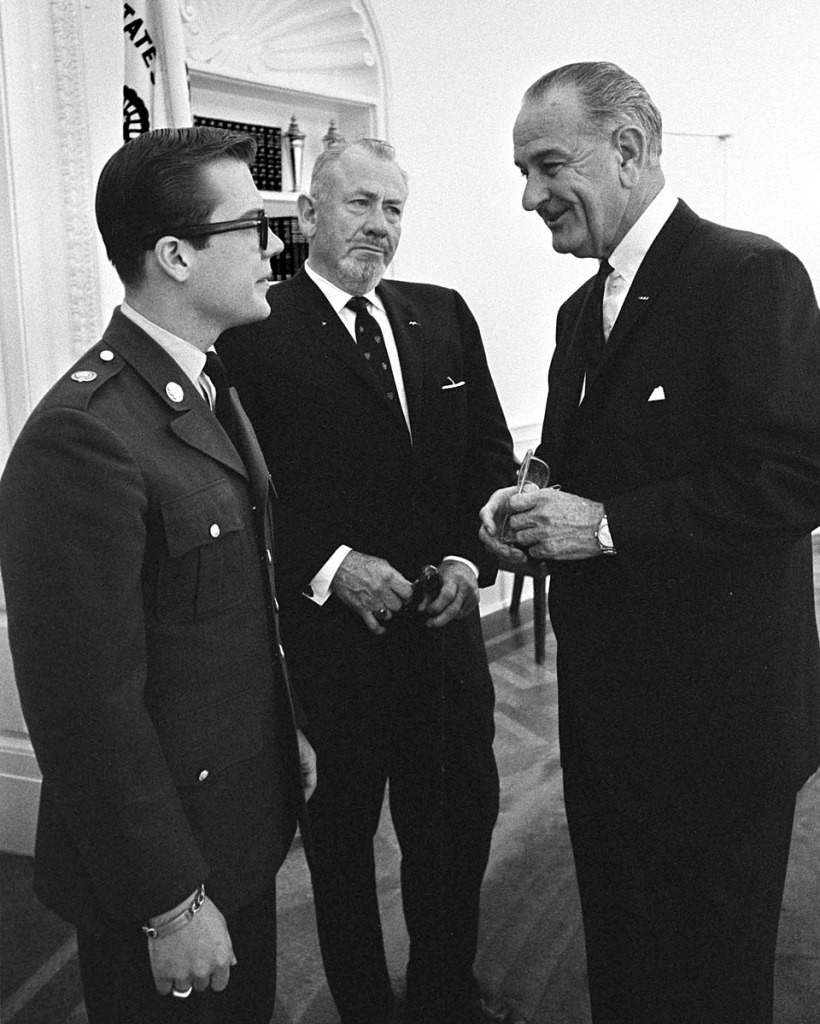

Yet, only a few hundred pages later in the book, in 1966, Steinbeck is writing to LBJ telling him not to get discouraged by anti-Vietnam War protestors:

I know that you must be disturbed by the demonstrations against policy in Vietnam. But please remember that there have always been people who insisted on their right to choose the war in which they would fight to defend their country. There were many who would have no part of Mr.

Adams’ and George Washington’s war. We call them Tories.

There were many also who called General Jackson a butcher. Some of these showed their disapproval by selling beef to the British. Then there were the very many who de nounced and even impeded Mr. Lincoln’s war. We call them Copperheads. I remind you of these things, Mr. President, because sometimes, the shrill squeaking of people who simply do not wish to be disturbed must be saddening to you. I assure you that only mediocrity escapes criticism.

The context there was that Steinbeck’s son was headed to Vietnam.

After his service John IV apparently became an anti-war advocate and Buddhist practioner:

He wrote about his experiences with the Vietnamese and GIs. Steinbeck took the vows of a Buddhist monk while living on Phoenix Island in the Mekong Delta, under the tutelage of the Coconut Monk, a silent tree-dwelling mystic yogi who adopted Steinbeck as a spiritual son. Amid the raging war, Steinbeck stayed in the monk’s “peace zone”, where the 400 monks who lived on the island hammered howitzer shell casings into bells.

Steinbeck’s politics are a whole academic mini-field: type “Steinbeck’s politics” into Jstor and 1,339 results come up.

The shifting meanings of conservative and liberal and associated ideas are interesting. If Hemingway and Fitzgerald had lived long enough, I’m sure their political transitions would’ve been quite interesting as well. I’m interested in the idea of America as a spoiled child on Christmas morning.

From an interview with William Souder, author of Mad At The World: A Life of John Steinbeck:

Library of America: Let’s start with your very evocative title. What was Steinbeck so mad about?

William Souder: It’s tempting to say “everything,” and let it go at that. Steinbeck was, in so many ways, America’s most pissed-off writer. In grade school, he befriended a classmate who was shy and got picked on. When he was asked why he wasted time with a boy nobody else liked, Steinbeck answered simply, “Because somebody has to take care of him.” Steinbeck could never abide a bully. Later, as a writer, Steinbeck filled his stories with people who were marginalized in a world he perceived in stark black-and-white.

Steinbeck believed in good and evil, and he was convinced that morality was inversely proportional to your lot in life. Being good too often meant having little to show for it, he thought. This was especially true during the Great Depression, when millions of honest, hard-working citizens were dispossessed and displaced—many of them Dust Bowl refugees who ended up toiling for appallingly low wages in California’s farm fields. Steinbeck investigated the plight of the “Okies” and saw firsthand their squalid roadside camps, haunted by disease and starvation. The migrants were brutalized by the landowners who needed them and also despised them.

In 1938, Steinbeck, who thought the confrontations between the migrants and the landowners’ squads of vigilante enforcers could escalate into civil war, began work on a novel about the situation, focusing it on the oppressive tactics of the big farm interests. After a few months he tore up the manuscript and started over, telling the story this time from the point of view of the oppressed—a family named Joad from Oklahoma. Steinbeck, seething and telling himself again and again to work slowly and carefully, wrote The Grapes of Wrath, long since acclaimed as one of the greatest books in the American canon, in a rage and in a rush. He didn’t have to push himself. He was fueled by anger.

Elmore Leonard on what Steinbeck taught him.

Our previous coverage of John Steinbeck.

Bluebeard’s Castle by Anna Biller

Posted: September 2, 2023 Filed under: Hollywood, Steinbeck, writing Leave a comment

Anna Biller is herself an exciting, energetic book reviewer. See for example her review of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, or her other Goodreads reviews. So we’ll try to bring you the same as we review her upcoming novel, Bluebeard’s Castle.

We requested a review copy because we’re Anna Biller fans after watching the 2016 film The Love Witch. This movie can be called a cult classic. A term like that and what it says is the sort of concept Biller herself might interrogate in one of the essays on her website.

The great thing about The Love Witch is that it’s totally unique. Who else is doing this? What’s another movie like this? It’s amazing that a movie like that exists. You can feel this is a project from someone with a singular vision. The Love Witch is striking, funny, odd, with a style that’s both homage and sendup of sort of 60s-70s Vincent Price era glam horror? After seeing it we followed Anna Biller on Twitter, where she mixes it up, mostly about film, in a fun way. Really though our way in is the director’s longer pieces of writing, like this account of the awfulness of working in a Honolulu hostess bar.

Bluebeard’s Castle is exactly what it purports to be, a retelling of the Bluebeard fairy tale/story/case study. But it’s more, a kind of play on the whole idea of the gothic novel, done with enthusiasm. A striking feature of it is that while it’s specific (we learn what people eat:

) the story also plays in a dreamlike timelessness.

Very cool and thrilling, even just on the sentence level. Nothing here is as it seems.

A+, excited to see the reaction when this book is released on October 10, 2023. Great for Halloween.

John Steinbeck on San Francisco

Posted: August 23, 2022 Filed under: San Francisco, Steinbeck, Steinbeck, the California Condition Leave a commentThomas Wolf took that one for Wikipedia.

Can you remember anywhere in John Steinbeck’s fiction where he discusses San Francisco? Whole books about Monterey, but does he even mention the place? I couldn’t remember. A friend’s been working on Steinbeck’s letters, he couldn’t think of any mention either.

Turns out Steinbeck does talk about San Francisco in Travels with Charley in Search of America. The chapter begins:

I find it difficult to write about my native place, northern California. It should be easiest, because I knew that strip angled against the Pacific better than any place in the world. But I find it not one thing but many – one printed over another until the whole thing blurs.

He mentions growth:

I remember Salinas, the town of my birth, when it proudly announced four thousand citizens. Now it is eighty thousand and leaping pell mell on in mathematical progression – a hundred thousand in three years and perhaps two hundred thousand in ten, with no end in sight.

(The population of Salinas is, in 2022, 156,77.)

Then he writes some about mobile home parks, and property taxes, concluding:

We have in the past been forced into reluctant change by weather, calamity, and plague. Now the pressure comes from our biologic success as a species.

Then he gets going on San Francisco:

Once I knew the City very well, spent my attic days there, while others were being a lost generation in Paris. I fledged in San Francisco, climbed its hills, splet in its parks, worked on its docks, marched and shouted in its revolts. In a way I felt I owned the City as much as it owned me.

…

A city on hills has it over flat-land places. New York makes its own hills with craning buildings, but this gold and white acropolis rising wave on wave against the blue of the Pacific sky was a stunning thing, a painted thing like a picture of a medieval Italian city which can never have existed.

Steinbeck can’t stay though. He has to hurry on to Monterey to cast his absentee ballot (it’s 1960; he’s voting for John F. Kennedy).

Oroville

Posted: December 2, 2021 Filed under: Steinbeck, the California Condition Leave a comment

In August, the state had to take the hydroelectric power plant at Lake Oroville, the second-biggest reservoir in California, off line for the first time since it was built in 1967 because the water level in the lake was too low.

“California Will Curtail Water to Farms and Cities Next Year as Drought Worsens” by Michael B Marois over in Bloomberg. Imagine taking a power plant offline. Who makes that call? Did the engineers kind of enjoy the challenge?

The shutdown isn’t even what’s referred to when we talk about the Oroville Dam Crisis. Had a chance to drive through Oroville last summer, there are many beautiful old houses, and the downtown has a lost in time feel. If you want to see what Steinbeck’s California might’ve been like, Oroville might be a better main street time capsule than Salinas.

On August 7, 1881, pioneer Jack Crum was allegedly stomped to death by local bully Tom Noacks in Chico, California. The young Noacks was feared by the locals of Butte County, not only because of his size and strength, but allegedly because he was mentally unbalanced and enjoyed punching oxen in the head.

Noacks was arrested and jailed in the Chico jail. Once word got out that the old pioneer had been murdered, the authorities moved Noacks to the Butte County county jail in Oroville for his safety. Crum’s friends, knowing that Noacks was in the county jail, made their way to Oroville with rope in hand. Knocking on the jail door, the men told the jailer that they had a prisoner from the town of Biggs, California. Once inside the jail, they overpowered the jailer and dragged Noacks from his cell. They took Noacks to Crum’s former farm and hanged him from an old cottonwood tree. Nobody was ever prosecuted for the lynching.

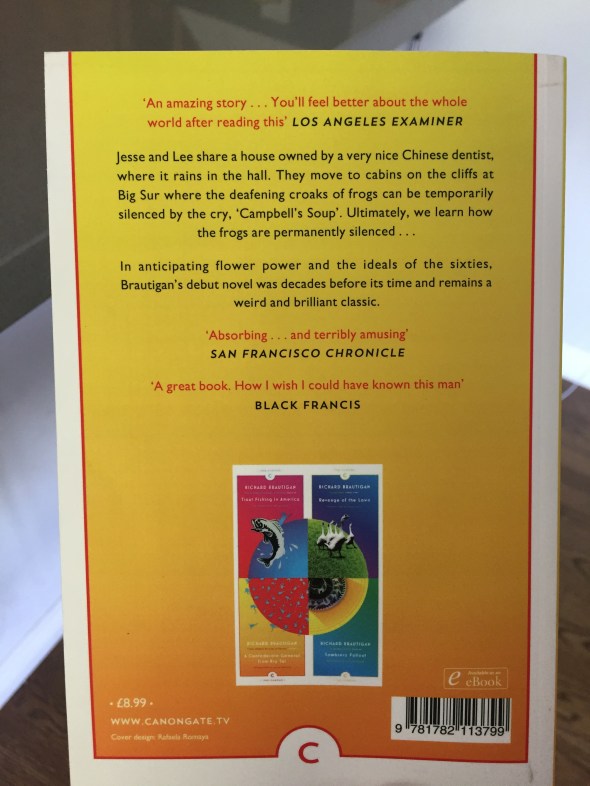

A Confederate General from Big Sur by Richard Brautigan

Posted: February 18, 2018 Filed under: Steinbeck, the California Condition, writing Leave a comment

It was during the second day of the Battle of the Wilderness. A. P. Hill’s brave but exhausted confederate troops had been hit at daybreak by Union General Hancock’s II Corps of 30,000 men. A. P. Hill’s troops were shattered by the attack and fell back in defeat and confusion along the Orange Plank Road.

Twenty-eight-year-old Colonel William Poague, the South’s fine artillery man, waited with sixteen guns in one of the few clearings in the Wilderness, Widow Tapp’s farm. Colonel Poague had his guns loaded with antipersonnel ammunition and opened fire as soon as A. P. Hill’s men had barely fled the Orange Plank Road.

The Union assault funneled itself right into a vision of scupltured artillery fire, and the Union troops suddenly found pieces of flying marble breaking their centers and breaking their edges. At the instant of contact, history transformed their bodies into statues. They didn’t like it, and the assault began to back up along the Orange Plank Road. What a nice name for a road.

On title alone this book had me. I’d never read Brautigan, cult hero of the age when the Army was giving LSD to draftees. This one came out in 1964.

Most of the book tells the story of the narrator living rough in Big Sur with Lee Mellon, who is convinced he’s descended from a Confederate general.

I met Mellon five years ago in San Francisco. It was spring. He had just “hitch-hiked” up from Big Sur. Along the way a rich queer stopped and picked Lee Mellon up in a sports car. The rich queer offered Lee Mellon ten dollars to commit an act of oral outrage.

Lee Mellon said all right and they stopped at some lonely place where there were trees leading back into the mountains, joining up with a forest way back in there, and then the forest went over the top of the mountains.

“After you,” Lee Mellon said, and they walked back into the trees, the rich queer leading the way. Lee Mellon picked up a rock and bashed the rich queer in the head with it.

At times reading this book felt like talking to a person who is on drugs when you yourself are not on drugs. By the end of this short book it felt little tedious. The semi-jokes seemed more like dodges.

Still, Brautigan has an infectious style.

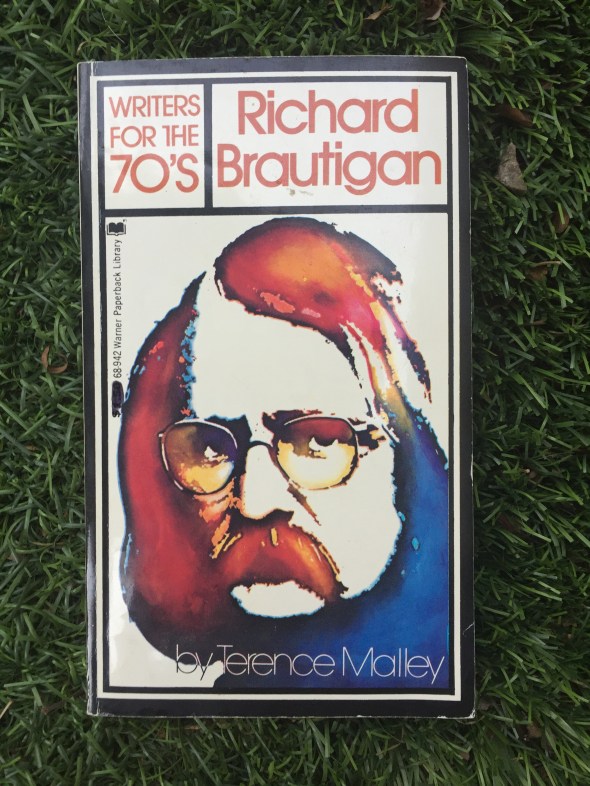

Mallley says:

Like much of Brautigan’s work, Confederate General belongs, at least partly, to a broad category of American literature – stories dealing with a man going off alone (or two men going off together), away from the complex problems and frustrations of society into a simpler world closer to nature, whether in the woods, in the mountains, on the river, wherever.

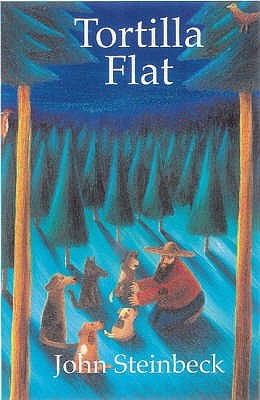

For a more satisfying read on men going off away from the complex problems and frustrations of society in the same region, I might recommend:

or

but it’s short and alive. The few short passages about the Civil War were my favorite.

We left with the muscatel and went up to the Ina Coolbrith Park on Vallejo Street. She was a poet contemporary of Mark Twain and Brett Harte during that great San Francisco literary renaissance of the 1860s.

Then Ina Coolbrith was an Oakland librarian for thirty-two years and first delivered books into the hands of the child Jack London. She was born in 1841 and died in 1928: “Loved Laurel-Crowned Poet of California,” and she was the same woman whose husband took a shot at her with a rifle in 1861. He missed.

“Here’s to General Augustus Mellon, Flower of Southern Chivalry and Lion of the Battlefield!” Lee Mellon said, taking the cap off four pounds of muscatel.

We drank the four pounds of muscatel in the Ina Coolbrith Park, looking down Vallejo Street to San Francisco Bay and how the sunny morning was upon it and a barge of railroad cars going across to Marin County.

“What a warrior,” Lee Mellon said, putting the last 1/3 ounce of muscatel, “the corner,” in his mouth.

As for Brautigan:

According to Michael Caines, writing in the Times Literary Supplement, the story that Brautigan left a suicide note that simply read: “Messy, isn’t it?” is apocryphal.

Writers in Hollywood

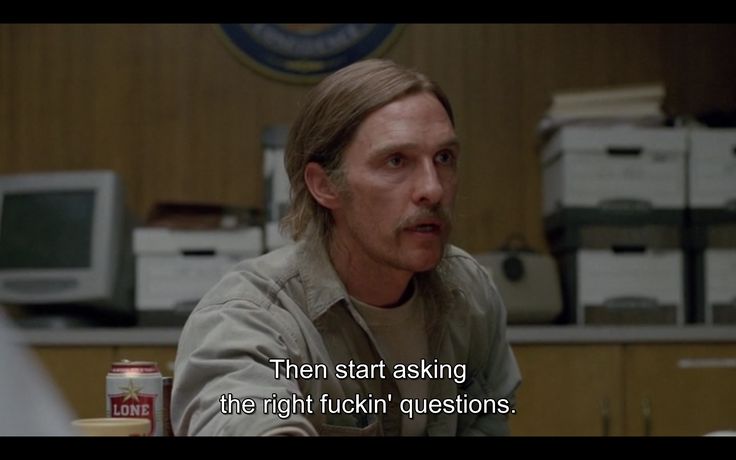

Posted: June 12, 2015 Filed under: actors, fscottfitzgerald, Hollywood, screenwriting, Steinbeck, the California Condition, TV, writing 1 CommentI spent the ensuing weeks across a table from Nic, hashing out plotlines. It gave me a chance to study him at close quarters. No one was more vehement about character and motivation than Nic. Now and then, he’d do the voices or act out a scene, turning his wrist to demonstrate the pop-pop of gunplay. He was 37 but somehow ageless. He could’ve stepped out of a novel by Steinbeck. The writer as crusader, chronicler of love and depravity. His shirt was rumpled, his hair mussed, his manner that of a man who’d just hiked along the railroad tracks or rolled out from under a box. He is fine-featured, with fierce eyes a little too small for his face. It gives him the aura of a bear or some other species of dangerous animal. When I was a boy and dreamed of literature, this is how I imagined a writer—a kind of outlaw, always ready to fight or go on a spree. After a few drinks, you realize the night will culminate with pledges of undying friendship or the two of you on the floor, trying to gouge each other’s eyes out.

I love True Detective and I loved, loved reading this profile of Nic Pizzolatto in Vanity Fair (from which I steal the above photo, credited to Art Streiber).

I did have a quibble, though.

Here’s what profile writer Rich Cohen says about F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood:

Early in the history of film, when the big-time writers of the day, Fitzgerald most famously, were offered a role in the movies, they decided to write for the cash, forswearing deeper participation in a medium they considered second-rate. Perhaps as a result of this decision, the author came to be the forgotten figure in Hollywood, well paid but disregarded. According to the old joke, “the actress was so stupid she slept with the writer.”

Later:

Credit and power are shared. But by tossing out that first season and beginning again, Nic has a chance to finally undo the early error of Fitzgerald and the rest. If he fails and the show tanks, he’ll be just another writer with one great big freakish hit. But if he succeeds, he will have generated a model in which the stars and the stories come and go but the writer remains as guru and king.

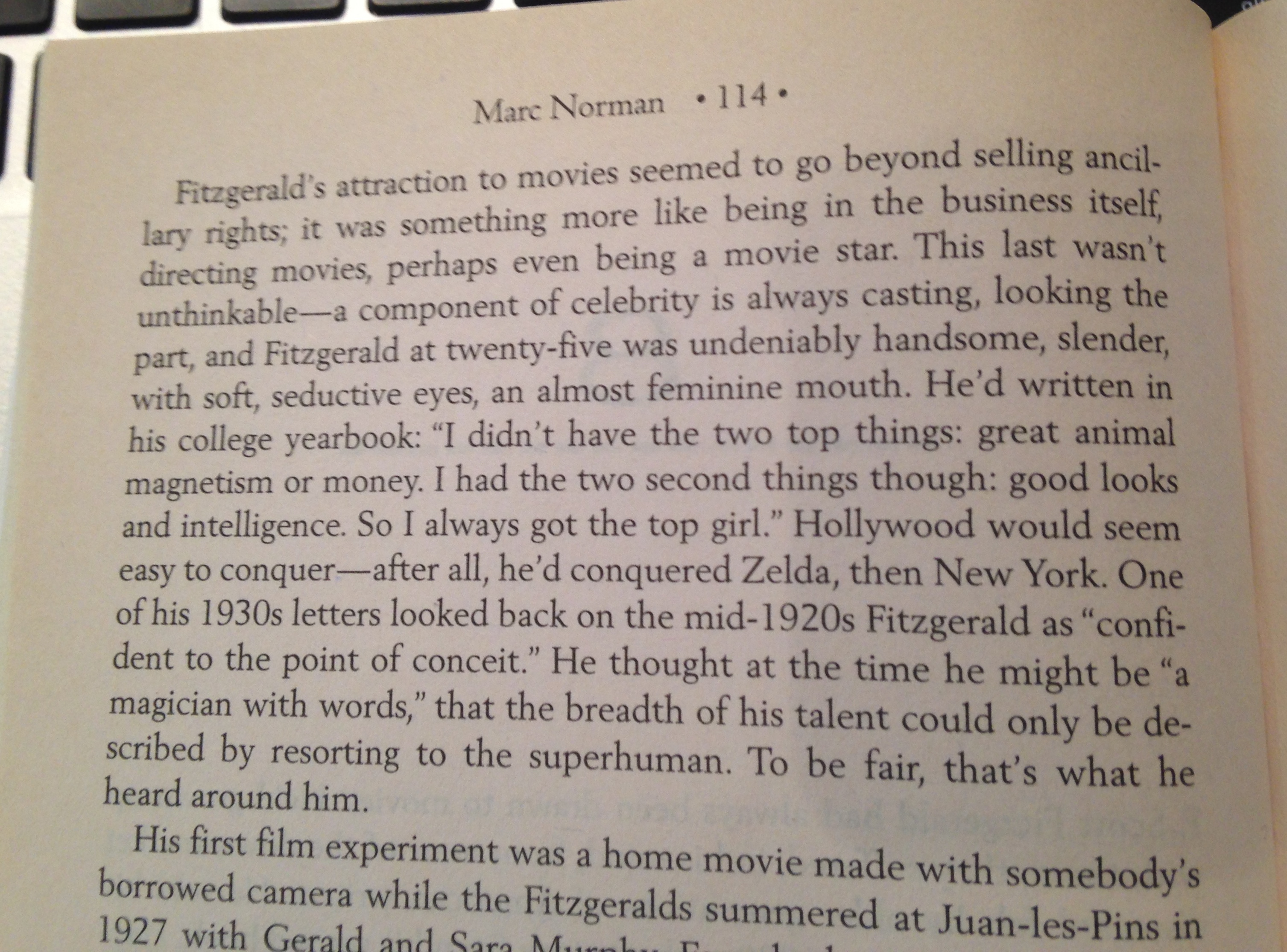

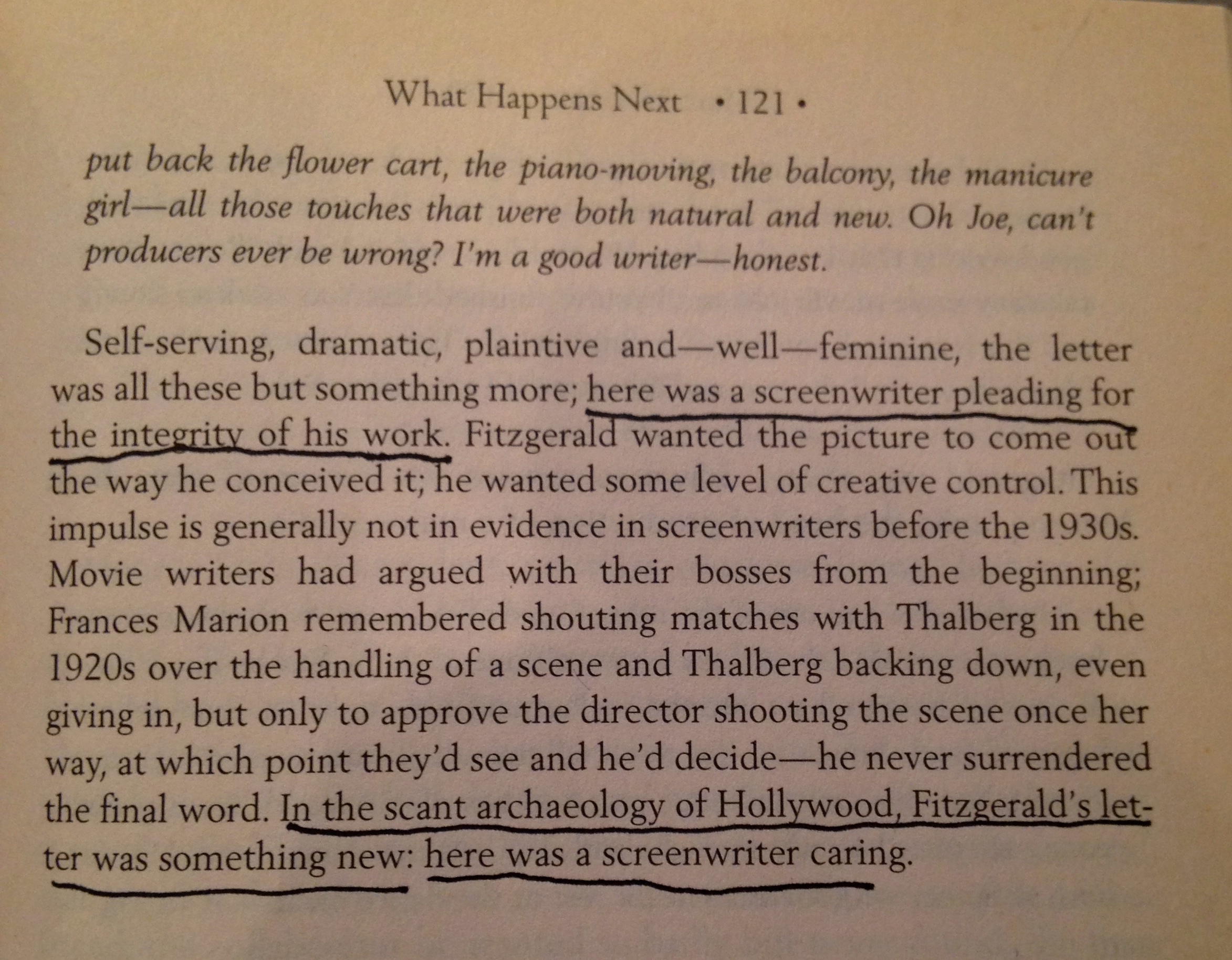

Not sure this is totally accurate. I’ve read a decent amount about F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. The more you read, the more it seems like Fitzgerald really loved Hollywood, and tried really hard to be good at writing movies, and was distressed by his failures. Fitzgerald loved movies:

When Fitzgerald worked on movies, it seems like he worked hard, was hurt when he was (frequently) fired, which sent him into tailspins that made things worse. But he was trying:

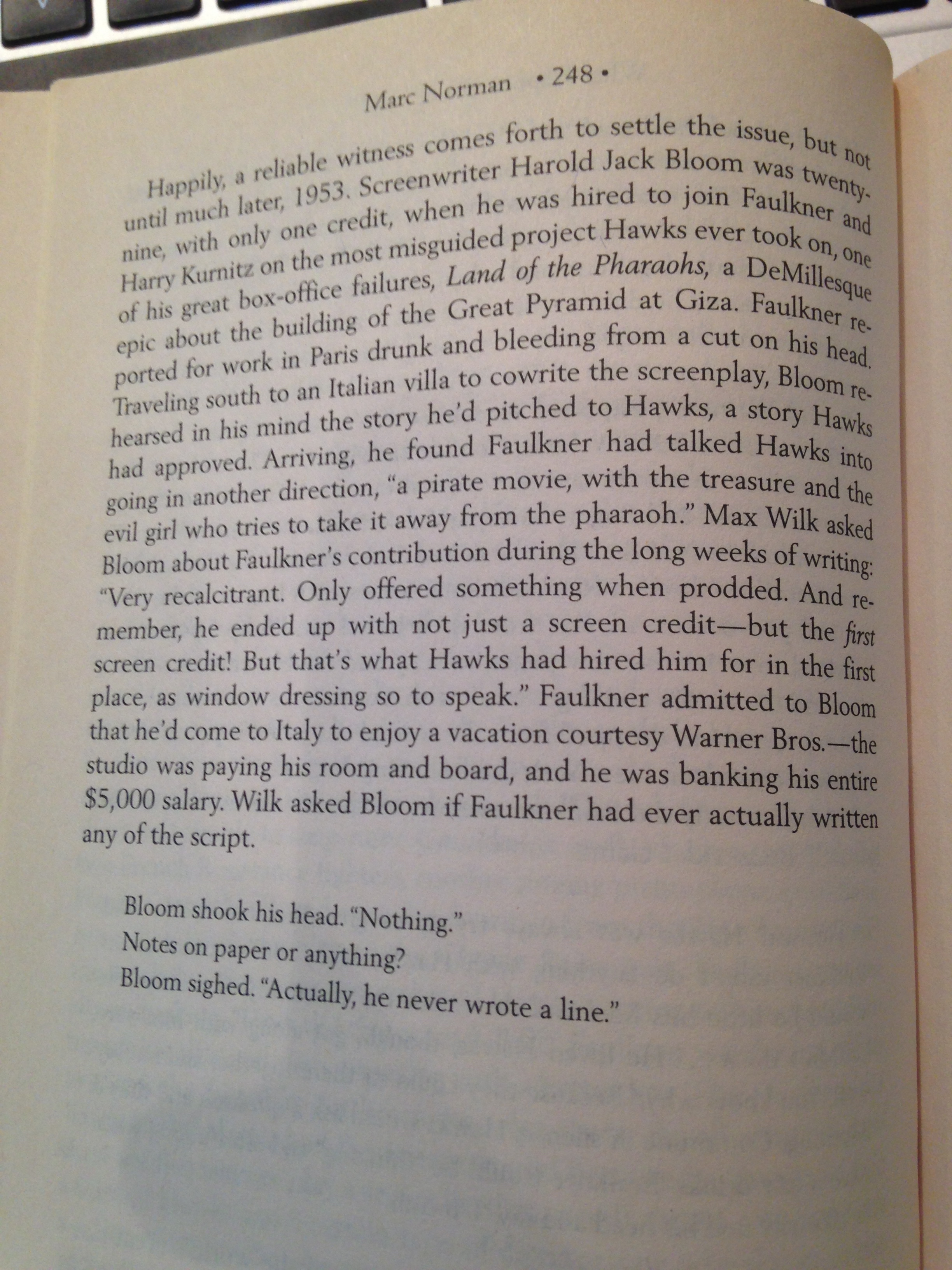

Those are from the great Marc Norman’s book, highly recommended:

Or how about this?:

That’s from this great one, by Scott Donaldson:

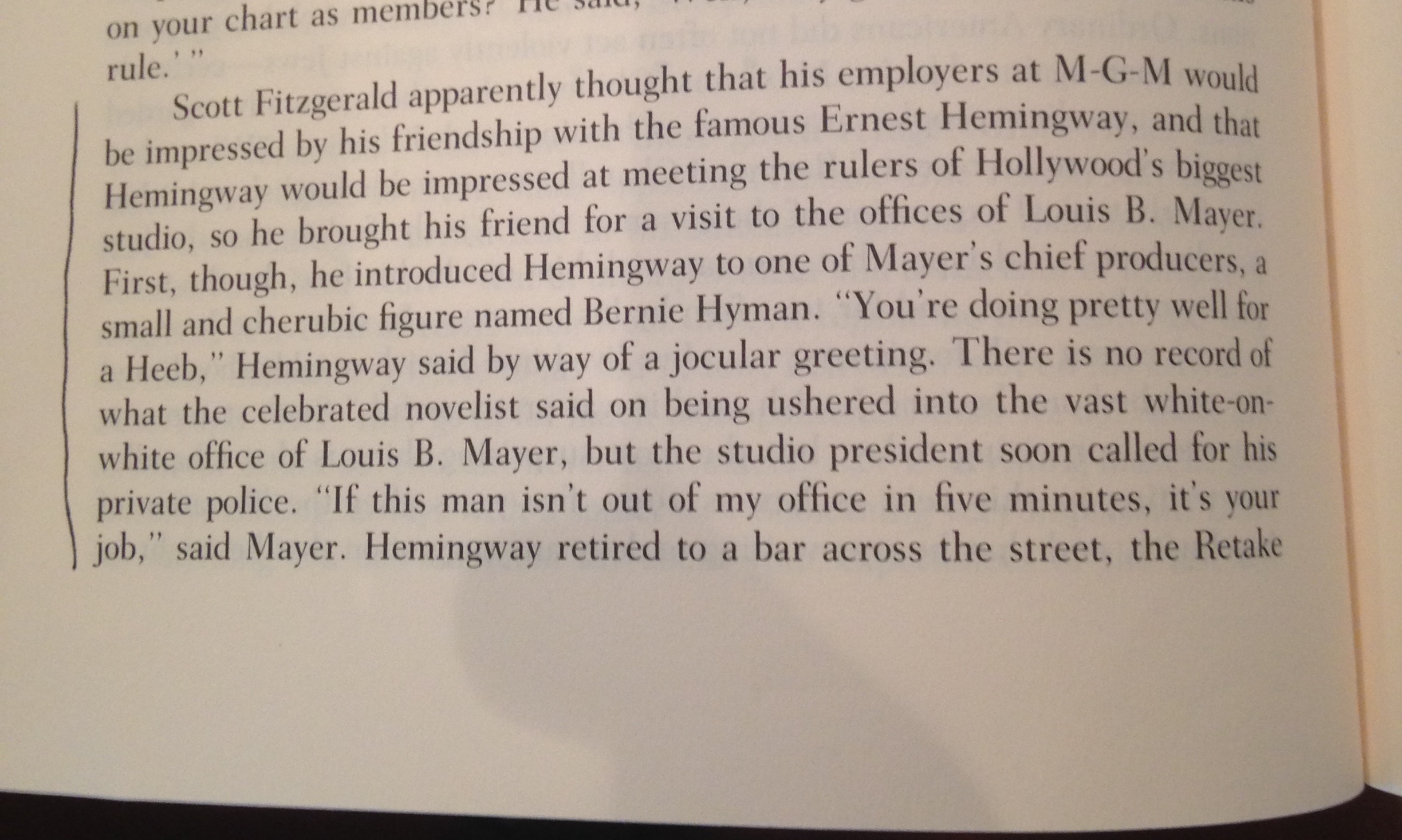

Now, that’s not to say that Fitzgerald always did everything perfectly:

(from this one, very entertaining read:

).

On the other hand, William Faulkner did well in Hollywood. He’s credited on at least two movies — The Big Sleep and To Have And Have Not, that you’d have to put in the all-time good list. If he’d never written a single book, you could look at those credits and call Faulkner a pretty successful screenwriter.

What did Faulkner do differently than Fitzgerald? Possibly, his secret was caring less:

Murky, to be sure.

But you might say: the big difference in the Hollywood careers of Fitzgerald and Faulkner is that Faulkner teamed with a great director, Howard Hawks, who liked him and liked working with him.

That’s what Pizzolatto did too. He teamed up with Cary Fukunaga. Cary Fukunaga directed all eight episodes of season one of True Detective (and a bunch of other things worth seeing).

Fukunaga’s not mentioned once in that Vanity Fair article. That’s crazy.

Anyway. I’m excited for season two, it sounds super interesting.

“In Shark’s life there had been no literary romance.”

Posted: April 4, 2012 Filed under: books, California, love, Steinbeck, Steinbeck Leave a commentIn Shark’s life there had been no literary romance. At nineteen he took Katherine Mullock to three dances because she was available. This started the machine of precedent and he married her because her family and all of the neighbors expected it. Katherine was not pretty, but she had the firm freshness of a new weed, and the bridling vigor of a young mare. After her marriage she lost her vigor and her freshness as a flower does once it has received pollen. Her face sagged, her hips broadened, and she entered into her second destiny, that of work.

In his treatment of her, Shark was neither tender nor cruel. He governed her with the same gentle inflexibility he used on horses. Cruelty would have seemed to him as foolish as indulgence. He never talked to her as to human, never spoke of his hopes or thoughts or failures, of his paper wealth nor of the peach crop. Katherine would have been puzzled and worried if he had. Her life was sufficiently complicated without the added burden of another’s thoughts and problems.

More, from Norman:

More, from Norman: