Good Press

Posted: June 18, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, everyone's a critic Leave a commentHaving a good press week:

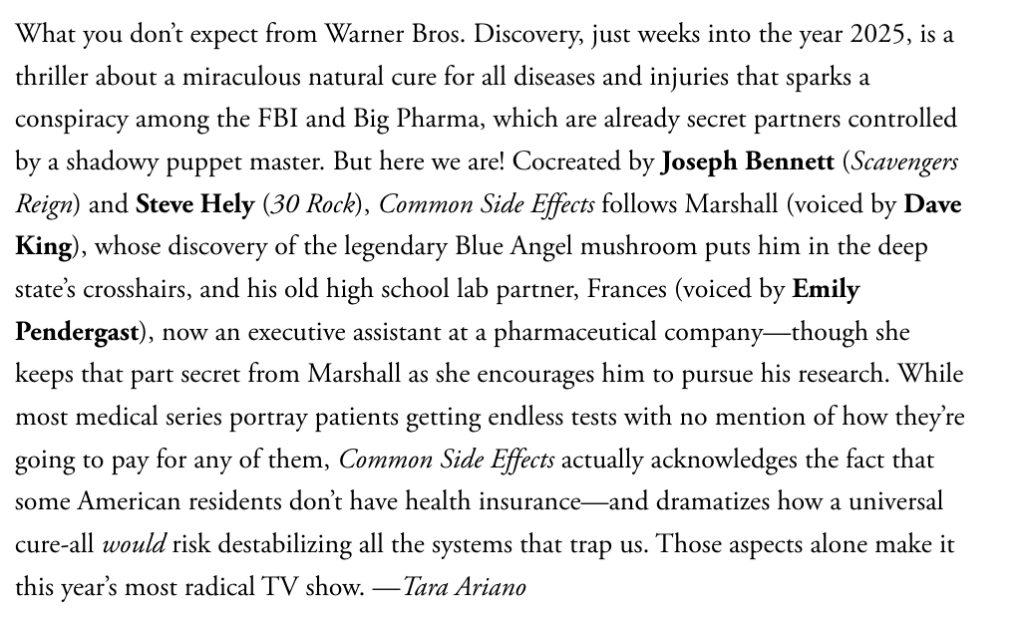

New York Times, The Best TV Shows of 2025 So Far

Vulture, 119 Books Every Comedy Fan Should Read

Hollywood Reporter, Ten Best TV Shows of 2025

Vanity Fair, The Best TV Shows of 2025 So Far.

Alan Sepinwall writing in Rolling Stone

You know what? Showbiz is mostly heartbreak and failure so we’re gonna celebrate our wins around here.

Years of Theory

Posted: October 25, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, everyone's a critic Leave a comment

Here’s an anecdote. One of Sartre’s closest friends in school was Raymond Aron, a conservative, pro-American political scientist. In those days, the French government had scholarships to various foreign countries. They started a whole French school in Brazil. Lévi-Strauss himself taught in that school and his early work is the result of that contact with Brazil. Roland Barthes taught on this scholarship in Egypt, because the French had a teaching fellowship in Cairo. There was one in Berlin, and when Aron had just gotten back he said, “There’s this thing called phenomenology. What does it mean?” He is sitting in a cafe with Sartre and Beauvoir, and Aron says, “What it means is: you can philosophize about that glass of beer.” Suddenly, the whole idea that phenomenology allowed one to think, write, and philosophize about elements of daily life transforms everything. As historically reconstructed by participants, the drink turns out to have been a crème de menthe, but that doesn’t matter too much. That’s the lesson that these people got from phenomenology, and that’s what seems to me to set off this immense period of liberation from philosophy, a liberation toward theory.

What is postmodern? Structuralist? When someone’s making a Marxist critique of like semiology, what’s happening?

Deluze. Sartre. Levi-Strauss. Lacan. Barthes. Foucault: who were these guys? what’s up here? What is the meaning of these names both as signifiers and signified and as referent?

Theory, structuralism, might not sound important. Academic stuff. Easy to dismiss. But guess what? Theory Thought has real, practical, worldly impact. These ideas are powerful.

The great sentence is not pronounced by Sartre but by Simone de Beauvoir: “On ne naît pas femme: on le devient.” 8 You aren’t born a woman: you become a woman. You are constructed and you construct yourself as a woman.

Interrogating, politicizing, gendering, queering, these are Theory ideas. Lived experience. My truth. The fathers of both Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg were Theory-adjacent professors, does that have any meaning? And DJT? The Theorists would say of course, a media figure whose words have no meaning and every meaning? who cannot be taken literally or seriously yet must only be taken literally and seriously? who seems to break reality by his very existence? create experiences across which no translation is possible? That was exactly what we’re talking about. This was the inevitable outcome. Don’t be mad at us for calling it.

Anxiety is: you can’t be free, and you can’t really be authentic, unless you feel anxiety. The French word is angoisse, so the translator is tempted to use the word “anguish,” which is the false friend, the immediate cognate of angoisse. Anguish, that makes it too metaphysical. In French, angoisse is an everyday word. At least angoissé( e). It means, I don’t have any cigarettes—can I go out? I’m waiting for a phone call. Then you’re angoissé( e). That doesn’t mean you’re in anguish, like one of the saints. It just means you have anxiety, and anxiety is an everyday experience.

Making thoughts actions, and words tools of power. Now, Theory would argue, twas ever thus we’re just pointing it out. Language has always been a tool of power. (But Theory would say that, wouldn’t it?)

Karl Marx was a Theorist. The master Theorist. His theory infected and took over huge portions of the world. Many millions died. There are places named after Karl Marx in Cuba Vietnam Russia China etc. All that from a theory he worked out over pints at a pub after doing his reading at The British Museum.

The Years of Theory: Lectures on Modern French Thought aka Postwar French Thought to the Present by Frederic Jameson may be one of the highest value books I ever bought. It is dense. But it’s less dense than Jameson’s other books, because it is transcripts of the guy talking.

If you’re very good at skipping/skimming huge parts of books, it’s fantastic. The drag may be sections where the ideas are so big, weird, vague or complicated that this reader found themself often saying “ok I’m moving on here because my mind is already blown and my circuits are fried.”

Now let’s look at this from a different point of view. We have said that each of these philosophical periods—Greece, the Germans, and now the French—are characterized by a problematic, but a changing problematic, a production of new problems. This is, in effect, Deleuze’s whole philosophy, the production of problems. But, if you put it that way, if you say philosophy’s task is the production of problems, what problems could there be if philosophy has come to an end? These problematics always end up producing a certain limit beyond which they are no longer productive.

The book functions pretty well as a history of France since WW2. Jameson quotes Sartre talking about the Occupation:

Never were we freer than under the German occupation. We had lost all our rights, beginning with the right to speak. We were insulted to our faces every day and had to remain silent. We were deported en masse as workers, Jews, or political prisoners. Everywhere—on the walls, on the movie screens, in the newspapers—we came up against the vile, insipid picture of ourselves our oppressors wanted to present to us. Because of all this, we were free. Because the Nazi venom seeped into our very thoughts, every accurate thought was a triumph. Because an all-powerful police force tried to gag us, every word became precious as a declaration of principle. Because we were wanted men and women, every one of our acts was a solemn commitment.

On the power and demise of the French Communist party:

The minute Mitterrand includes them in his government, they disappear. That’s the end of the Communist Party. After 1980, the Party is nothing. Of course, it is even less than nothing after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. There is still a Communist Party in France, of course, but its power is broken. Mitterrand’s political act here is a very cunning tactic of cooptation, which does them in as rivals to his socialist government, which itself ends up being not very socialist. But, in this period, the Party is a presence; it can irritate all these intellectuals. They revolt against it in various ways.

An idea: Theory begins for real after Camus. Camus says, man’s search for meaning? Forget it. No meaning. You’re pushing a rock up a hill. It’s absurd. Consider Sisyphus happy, live, move on.

Theory maybe says, sure ok but what even is Being? What is it that “we” (?) are experiencing? Jameson:

I’m alive in this moment when the sun is dying, or when climate change is destroying the planet, so many years from the big bang. So also with the body. I have a tendency to fat. Okay, that’s my situation. But I have to live that in some way. I have to choose that. So I keep dieting; I keep struggling against it. Or I let myself go completely. Or I become jolly like Falstaff. We are not free not to do something with this situation. Freedom is our choice of how we deal with it, but we have to deal with it, because it is us. But it’s not us in the way a thing is a thing. We are not our body. We are our body on the mode of not being it. We want people to understand that we are different, that we have a personality, that we’re not exactly what our body seems.

Here’s another one:

Everything we are we have to play at being, even if we don’t feel it that way. That’s a social function, so, of course, you have to rise to the occasion and play at being that social function.

Terry Eagleton, reviewing the book in the LRB, says:

and:

Theory was a big Yale and Duke and Brown thing. There was some of it at Harvard, but it’s not so easy to buy Theory when you remember Cotton Mather and John Adams and John Kennedy and Franklin Roosevelt.

I once interviewed an East German novelist who was quite interesting at the time, and we asked him the then-obvious question: “How much of an influence did Faulkner have on you?” As you know, after the war, all over the world, it is the example of Faulkner that sets everything going, from the Latin American boom to the newer Chinese novel. Faulkner is a seminal world influence at a certain moment. But what does that mean, “Faulkner’s influence”? So he said, “No, I never learned anything from Faulkner—except that you could write page after page of your novel in italics.”

Any time Jameson says “here’s a story for you” or “start with a bit of biography” I perk up. What would the narratologists say about that? Why are stories so addictive? So much more popular than Theory? To answer those questions would be to Theorize stories. Should you spend your time Theorizing stories? Or telling stories?

Why is this detail included in Jameson’s Wikipedia page?:

Both his parents had non-wage income over $50 in 1939 (about USD$1130 in 2024)).[12][15]

Amazing things happening in the Vertigo Sucks community

Posted: September 3, 2024 Filed under: everyone's a critic, film 1 Comment

The comments coming to life on our 2013 post. To be clear, our problem isn’t so much with Vertigo itself as with film critics who overhype it, hurting rather than helping the cause of old movie appreciation.

Movie Reviews: The Favourite, Mary Queen of Scots, Schindler’s List

Posted: December 14, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, everyone's a critic, film, movies, the California Condition, Uncategorized Leave a comment

Finding myself with an unexpectedly free afternoon, I went to see The Favourite at the Arclight,

You rarely see elderly people in central Hollywood, but they’re there at the movies at 2pm. While we waited for the movie to start, there was an audible electrical hum. The Arclight person introduced the film, and then one of the audience members shouted out “what’re you gonna do about the grounding hum?”

The use of the phrase “grounding hum” rather than just “that humming sound” seemed to baffle the Arclight worker. Panicked, she said she’d look into it, and if we wanted, we could be “set up with another movie.”

After like one minute I took the option to be set up with another movie because the hum was really annoying. Playing soon was Mary Queen of Scots.

Reminded as I thought about it of John Ford’s quote about Monument Valley. John Ford assembles the crew and says, we’re out here to shoot the most interesting thing in the world: the human face.

Both Saoirse Ronan and Margot Robbie have incredible faces. It’s glorious to see them. The best parts of this movie were closeups.

Next I saw Schindler’s List.

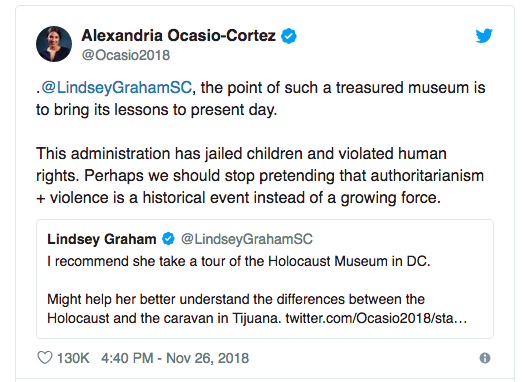

This movie has been re-released, with an intro from Spielberg, about the dangers of racism.

This movie knocked my socks off. I forgot, since the last time I saw it, what this movie accomplished.

When the movie first came out, the context in which people were prepared for it, discussed it, saw it, were shown it in school etc took it beyond the realm of like “a movie” and into some other world of experience and meaning.

I feel like I saw this movie for the first time on VHS tapes from the public library, although I believe we were shown the shower scene at school.

My idea in seeing it this time was to see it as a movie.

How did they make it? How does it work? What’s accomplished on the level of craft? Once we’ve handled the fact that we’re seeing a representation of the Holocaust, how does this work as a movie?

It’s incredible. The craft level accomplishment is on the absolute highest level.

Take away the weight with which this movie first reached us, with what it was attempting. Just approach it as “a filmmaker made this, put this together.”

Long, enormous shots of huge numbers of people, presented in ways that feel real, alive. Liam Neeson’s performance, his mysteries, his charisma, his ambiguity. We don’t actually learn that much about Oscar Schindler. So much is hidden.

Ralph Fiennes performance, the humanity, the realness he brings to someone whose crimes just overload the brain’s ability to process.

The moving parts, the train shots, the wide city shots. Unreal accomplishment of filmmaking.

Some thoughts:

- water, recurring as an image, theme in the movie.

- there are a bunch of scenes of just factory action, people making things with tools and machines. that was the cover. was not the Holocaust an event of the factory age, a twisted branch of Industrial Revolution and efficiency metric spirit?

- reminded that people didn’t know, when it began, “we’re in The Holocaust, this is the Holocaust.” It built. It got worse and worse. there were steps and stages along the way.

- what happened in the the Holocaust happened in a particular time and place in history, focused in an area of central and eastern Europe that had its own, centuries long, context for what you were, who belonged where, history, which tribes go where, what race or nationality meant, how these were understood. Göth’s speech about how the centuries of Jewish history in Kraków will become a rumor. I felt like this movie kind of captured and helped explain some of that, without a ton of extra labor.

- In a way Schindler could almost be seen as like a comic character. He didn’t start his company to save Jews. He starts it to make money from cheap labor. He’s a schemer who sees an opportunity. A rascal out to make a quick buck, a con man and shady dealer who ended up in the worst crime in history, an honest crook who finds he’s in something of vastness and evil beyond his ability to even comprehend.

- There is a scene in this movie that could almost be called funny, or at least comic, when Oscar Schindler (Neeson) tries to explain to Stern (Ben Kingsley) the good qualities of the concentration camp commandant Göth that nobody ever seems to mention!

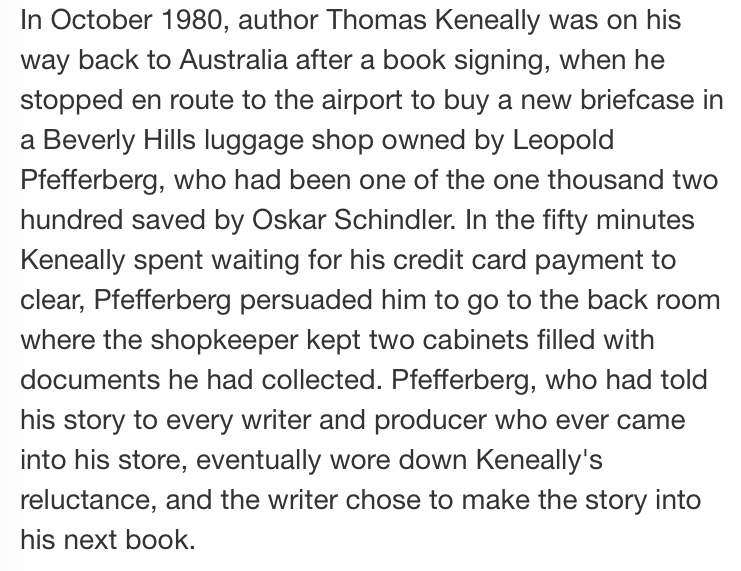

- Kenneally’s story of how he heard about Schindler:

- The theme of sexuality, Goth’s sexuality, Schindler’s, what it means to love and express your nature versus trying to suppress and kill. Spielberg is not really known for having tough explorations of sexuality in his films but I’d say he took this one pretty square on with a lot bravery?

- if I had a criticism it was maybe that the text on the little intermediary passages that appear on screen a few times and explain the context felt not that clear and kind of unnecessary.

- I feared this movie would have a kind of ’90s whitewash, I felt maybe takes exist, the “actually Schindler’s List is BAD” take is out there, with the idea being that Spielberg put in too much sugar with the medicine which when we talk about the Shoah, unspeakable, unaddressable, is somehow wrong, but damn. I was glad for the sugar myself and I don’t think Spielberg looked away. The Holocaust occurred in a human context, and human contexts, no matter how dark, always have absurdity.

- the scene, for instance, were the Nazis burn in an enormous pyre the months-buried, now exhumed bodies of thousands of people executed during the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto, Spielberg took us as close to the mouth of the abyss as you’re gonna see at a regular movie theater.

What does it mean that Spielberg made a movie about the Holocaust and the two leads are both handsome Nazis?

*As a boy I was attracted to the history of Britain and Ireland as well as Celtic and Anglo-Saxon peoples in America. The peoples of those islands recorded a dramatic history that I felt connected to. They also developed a compelling tradition of telling these history stories with as much drama and excitement as possible eg. Shakespeare.

At a library book sale, I bought, for 50 cents a volume, three biographies from a numbered set from like 1920 of “notable personages,” something like that.

These just looked like the kind of books that a cool gentleman had. Books that indicated status and intelligence.

One of this set that I got was Hernando Cortes. I started that one, but even at that tender age I perceived Cortes was not someone to get behind. The biography had a pro-Cortes slant I found distasteful.

Another volume was about Mary Queen of Scots.

Just on her name, really, I started reading that one.

Mary Queen of Scots’ life was a thrilling story, and this one was melodramatically told. Affairs, murder plots, insults, rumor, execution.

Sometime thereafter, at school, we were all assigned like a book report. To read a biography, any biography, and write a report about it.

Since I’d already read Mary’s biography, I picked her.

As it happened, I overheard my dad confusedly ask my mom why, of all people on Earth, I’d chosen Mary Queen of Scots as the topic for my biography project. My dad did not know the backstory, which my mom patiently explained.

My dad’s reaction on hearing I’d picked Mary Queen of Scots, while not as harsh as Kevin Hart’s imagined reaction on hearing his son had a dollhouse, helps me to understand where Kevin Hart was coming from. Confusion, for starters. Upsetness.

At the time the guys I thought were really heroes were probably like JFK and Hemingway.

England forever!

Posted: April 16, 2016 Filed under: everyone's a critic, Uncategorized, writing Leave a comment

From the Times Literary Supplement, this remarkable sentence in Geoffrey Wheatcroft’s review of Christopher Hitchens posthumous book of essays:

Born to a dyspeptic, reactionary naval officer and a mother whose Jewish origins Hitchens only discovered after her tragic suicide, he was educated at a modest public school and Oxford University, where he delightedly embarked on a double life – radical agitation by day, sybaritic lotus-eating by night – which set the tone for the years to come.

I can picture it.

Posted: October 25, 2013 Filed under: everyone's a critic 2 Comments

10.[Wes Anderson] became close friends with Owen Wilson because Owen Wilson just suddenly started acting as if they were close friends.

Anderson and his frequent leading man and sometime screenwriting collaborator took a playwriting class together at the University of Texas at Austin, but they didn’t hang out or talk. Then one day Wilson came up to Anderson in the corridor of a building in the English department. “We were signing up for classes and he started asking me to help him figure out what he should do, as if we knew each other. As if we had ever spoken before or knew each other’s names. I almost feel like he was taking it for granted that if we didn’t know each other yet, soon we would.”

(from Matt Zoller Seitz roundup of Wes Anderson trivia he learned writing his book. Huge soft spot for MZS here at Helytimes from back when he was a heroic drum-banger for The New World)

(photo stolen from this mess)

Damn.

Posted: April 5, 2012 Filed under: everyone's a critic, film, SDB Leave a comment

I wish SDB were around to talk to me about Hunger Games. I would definitely be exhausted long before he was even warmed up.

I read 1/2 of the Hunger Games book. For that half, the book was “better” than the movie because there was much more backstory about Katniss and Peeta.

The book seemed to take place in a real, recognizable world. I did not feel this way in the movie. But if the movie were on that level of reality it would be too horrifying to make one billion dollars.

I thought the movie was shot kind of poorly. The forest never looked awesome enough. Maybe they should’ve gotten Debra Granik, who directed Winter’s Bone.

My favorite character was the Game Maker.

A complicated villain.

(photo from People Magazine’s website, where it is used to illustrate an article about “Why Wes Bentley’s ‘Hunger Games’ Beard Drew Stares Off Set.” The answer is because “while the beard’s futuristic design certainly fit in with the film’s stylized setting, it was less suited to rural North Carolina, where the cast and crew shot.”)

The Civil Wars

Posted: March 30, 2012 Filed under: everyone's a critic, music Leave a commentThe Civil Wars won the Grammy for Best Country Duo/Group Performance and for Best Folk Album of 2012. I’d never heard of them until then. I’ll be impressed if you can get through one of their videos without getting massively douched out:

The duo’s web site says that the name of their band, The Civil Wars, and their thematic direction, is best summed up in the lyrics of the song “Poison & Wine”. It is about the good, the bad, and the ugly of married life.