Granger seen anew

Posted: June 18, 2025 Filed under: Texas, War of the Rebellion Leave a comment

With Juneteenth coming up we once again turn our thoughts to Gordon Granger. It was he who issued the famous General Order #3 at Galveston in 1865 (better late than never):

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.

The newly freed were slammed pretty fast into capitalism:

The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Geez, not even a small vacation?

We’ve covered Granger before – Grant didn’t like him. But in Charles Dana’s Recollections of the Civil War we came across some new (to us) material that brought the man to life:

After Chickamauga:

Our troops were as immovable as the rocks they stood on. Longstreet hurled against them repeatedly the dense columns which had routed Davis and Sheridan in the early afternoon, but every onset was repulsed with dreadful slaughter. Falling first on one and then another point of our lines, for hours the rebels vainly sought to break them. Thomas seemed to have filled every soldier with his own unconquerable firmness, and Granger, his hat torn by bullets, raged like a lion wherever the combat was hottest with the electrical courage of a Ney. When night fell, this body of heroes stood on the same ground they had occupied in the morning, their spirit unbroken, but their numbers greatly diminished.

Later, in the same campaign, Granger can’t stop firing a cannon personally:

The enemy kept firing shells at us, I remember, from the ridge opposite. They had got the range so well that the shells burst pretty near the top of the elevation where we were, and when we saw them coming we would duck-that is, everybody did except Generals Grant and Thomas and Gordon Granger. It was not according to their dignity to go down on their marrow bones. While we were there Granger got a cannon—how he got it I do not know-and he would load it with the help of one soldier and fire it himself over at the ridge. I recollect that Rawlins was very much disgusted at the guerilla operations of Granger, and induced Grant to order him to join his troops elsewhere.

As we thought we perceived, soon after noon, that the enemy had sent a great mass of their troops to crush Sherman, Grant gave orders at two o’clock for an assault upon the left of their lines; but owing to the fault of Granger, who was boyishly intent upon firing his gun instead of commanding his corps, Grant’s order was not transmitted to the division commanders until he repeated it an hour later.

He can’t stop driving Grant nuts:

The enemy was now divided. Bragg was flying toward Rome and Atlanta, and Longstreet was in East Tennessee besieging Burnside. Our victorious army was between them. The first thought was, of course, to relieve Burnside, and Grant ordered Granger with the Fourth Corps instantly forward to his aid, taking pains to write Granger a personal letter, explaining the exigencies of the case and the imperative need of energy.

It had no effect, however, in hastening the movement, and a day or two later Grant ordered Sherman to assume command of all the forces operating from the south to save Knoxville. Grant became imbued with a strong prejudice against Granger from this circumstance.

Finding water on the plains

Posted: February 8, 2025 Filed under: Texas 1 Comment

“You can blindfold me, me, take me anywhere in the Westen country; Goodnight once said, ‘then uncover my eyes so that I can look at the vegetation, and I can tell about where I am.

The mesquite, for instance, has different forms for varying ali. tudes, latitudes, and areas of aridity. It does not grow lat north of old Tascosa in the Texas Panhandle.

‘When I was scouting on the Plains, I was always mighty glad to see a mesquite bush. In a dry climate — the climate natural to the mesquite — its seed seem to spring up only from the droppings of an animal. The only animal on the Plains that ate mesquite beans was the mustang. After the mesquite seed was soaked for a while in the bowels of a horse and was dropped, it germinated quickly. Now mustangs rarely grazed out from water more than three miles, that is, when they had the country to themselves. Therefore, when I saw a mesquite bush I used to know that water was within three miles. All I had to do after seeing the bush was to locate the direction of the water.

“The scout had to be familiar with the birds of the region,” continued the plainsman, ‘to know those that watered each day, like the dove, and those that lived long without watering, like the Mexican quail. On the Plains, of an evening, he could take the course of the doves as they went off into the breaks to water. But the easiest of all birds to judge from was that known on the Plains as the dirt-dauber or swallow. He flew low, and if his mouth was empty he was going to water. He went straight too. If his mouth had mud in it, he was coming straight from water. The scout also had to be able to watch the animals, and from them learn where water was. Mustangs watered daily, at least in the summertime, while antelopes sometimes went for months without water at all. If mustangs were strung out and walking steadily along, they were going to water. If they were scattered, frequently stopping to take a bite of grass, they were coming from water.

‘West of the Cross Timbers water became very scarce, and near the Plains extremely bad. Most of it was undrinkable, and the water we could drink had a bad effect on us. At times we suffered exceedingly from thirst, which sufiering is the worst torture of all. At night we tossed in a semi-conscious slumber in which we unfortunately dreamed of every spring we ever knew — and such draughts as we would take from them – which invariably awakened us, leaving us, if possible, in even more distress. In my early childhood we had a fine spring near the house under some large oaks. A hollow tree had been provided for a gum, as was common in those days, and was nicely covered with green moss. Many times I have dreamed of seeing that spring and drinking out of it — it would seem so very real!

‘Suffering from thirst had a strange and peculiar effect. Every ounce of moisture seemed to be sapped out of the flesh, leaving men and animals haggard and thin, so that one could not recognize them if they had been deprived long.

‘Interior recruits had little knowledge of how to take care of themselves in such emergencies. In case of dire thirst, placing a small pebble in the mouth will help, a bullet is better, a piece of copper, if obtainable, is still better, and prickly pear is the best of all. Of course there were no pears on the Plains, but in the prairie country there were many. If, after cutting off the stickers and peeling, you place a piece of the pear in your mouth, it will keep your mouth moist indefinitely. If your drinking water happens to be muddy, peel and place a thin slice of pear in it. All sediment will adhere to it and it will sink to the bottom, leaving the water clear and wholesome.”

Simple, you just see if a swallow’s mouth is muddy. Charles Goodnight was hardcore. Following doves through the breaks is not easy.

Texas Wines

Posted: January 25, 2025 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

(source. post title can be sung to the tune of Khuangbin and Leon Bridges, “Texas Sun”)

From my father in law I came into possession of several bottles of Texas wine.

Texas has the most native grapes of any state, we are told by Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson in their World Atlas of Wine (8th Edition), but these are not vinifera, the species of grape we’re usually talking about to make wines. You can make wines out of other grapes, but they tend to have a quality described as “foxy,” which seems to be like musty. The Concord grape’s taste is sometimes suggested as a referent.

Johnson and Robinson:

Of the 65-70 species of the genus Vitis scattered around the world, no fewer than 15 are Texas natives – a fact that was turned to important use during the phylloxera epidemic. Thomas V Munson of Denison, Texas, made hundreds of hybrids between Vitis vinifera and indigenous vines in his eventually successful search for immune rootstock. It was a Texan who saved not only France’s but the whole world’s wine industry.

they continue:

As much as 80% of all Texas wine grapes are grown in the High Plains, but about three-quarters of them are shipped to one of the 50 or so wineries in the Hill Country of Central Texas, west of Austin. The vast Texas Hill Country AVA is the second most extensive in the US, and includes both the Fredericksburg and Bell Mountain AVAs within it. The total area of these three AVAs is 9 million acres (3.6 million ha), but a mere 800 acres (324ha) are planted with vines.

Their map:

Of these wines, Pedernales Block 2 was most impressive to me. This could be a competition wine. Set it against your French and Spanish and Italian and California wines and see if it can’t hold up.

It looks like Kuhlken Vineyards is right across the river from Lyndon Johnson’s ranch. He used to drive his amphibious car in the Pedernales.

(source)

Now, if you’re looking for structure in your wines, Texas ain’t the place.

This one initially smelled of sweet barbecue sauce. Not saying that’s a bad thing, just something you should know. I would say it “opened up” most generously and I respected this wine, I felt like by the time I’d finished a glass this wine and I were pals.

The Davis Mountains AVA seems like more a hope than a real center of production for now, but someday it could be really special. Next time I’m in Marfa I will try Alta Marfa wines.

How much wine do you think you need to drink to become a professional wine critic?

Lettie Teague of the WSJ my model here. I think I drink a reasonable amount of wine, but probably not even close to the professional level.

The way in to wine for me is geography. Tastes and notes are fine to discuss at the tasting room but I want to go to the Margaret River and the base of Etna and Yountville and St. Emilion and yes, even Lubbock. The Hill Country for sure.

My mother in law was a pioneer of Texas wine writing, I wish I could discuss these wines with her. She has gone to the great AVA in the sky.

A galled crotch

Posted: November 13, 2024 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

Reading at last J. Evetts Hayley’s biography of Charles Goodnight.

Teddy Blue

Posted: July 29, 2024 Filed under: cormac, Texas, the American West Leave a commentI’ve been working my way through Larry McMurtry’s short syllabus for understanding the cowboy of the 19th century. Teddy Blue’s memoir is vivid:

A Yankee cowboy:

Conversation with a chippie:

(Gilt Edge appears to be no more).

strong phrase:

Reminded of Cormac McCarthy: I’d know your hide in a tanyard. Teddy weighs in on cowboy songs:

I like the version by Suzanne Vega.

JAB III

Posted: June 4, 2023 Filed under: America Since 1945, Texas Leave a commentJames Baker signed memos JAB III but he was really James Baker IV. All the previous Jameses Baker had been powerful lawyers and fixers in Houston, Texas. They had nicknames, more like titles. The Judge, etc. The first James Baker, our James Baker’s great-grandfather, knew Sam Houston. The Bakers played a role in the opening of Houston’s ship channel, enabling the city to outflank and overtake Galveston. (A side benefit of this book is the early pages provide a pretty good history of Houston).

JAB III might’ve ended as another in this line, quiet, forceful, but not a national figure, had he not met a remarkable transplant to Texas named George Herbert Walker Bush. The two of them shared weighty lineages, prep and Ivy League backgrounds. They formed a brotherly relationship, they were doubles tennis partners (club champions, these guys play to win). The rise of one was linked to the rise of the other.

Baker was that way because of who he was and where he came from, and it was his strange luck, and the country’s, that he happened to be ready to leave his hometown and legal career behind at just the moment when the entire Republican elite had been decimated by Richard Nixon’s Watergate disaster.

Secretary of State, Secretary of the Treasury, Under Secretary of Commerce, White House chief of staff for President Ronald Reagan, failed candidate for Attorney General of Texas, Marine officer, Princeton guy, elk killer.

Brokaw told him the key was understanding that Baker was a patient and expert turkey hunter. He would rise before dawn, dress in camouflage, venture out into the Texas heat and then sit there not so much as blinking. “And he waits and waits until he gets the turkey right where he wants it,” Brokaw told Netanyahu, “and then he blows its ass off.”

JAB III’s last major act in American politics* was presiding over the legal team that won the battle that gave George Herbert Walker Bush’s son, W Bush, the presidency. Whether on reflection the outcome of that victory is exactly the future JAB III would’ve wanted we can discuss later.

Cheney was thirty-five years old and, following Donald Rumsfeld’s promotion to defense secretary, had become the youngest man ever to serve as White House chief of staff. With the demeanor of a cool cowboy from Wyoming, the fierce intellect of a Yale dropout-turned-doctoral-candidate, and the discipline of a recovering drinker, Cheney had established himself as a force to be reckoned with in the White House

In 1980 JAB III was Bush’s guy, but Ronald Reagan picked him as his chief of staff. Why? JAB III outmaneuvered people who’d been around Reagan for years. How? That’s why I wanted to read this book. It was written by Peter Baker (no relation) and Susan Glasser, two NY Times reporters who are married. The book is snappy and good, recommend. As an act of service and review we prepared this summary for the busy executive.

Baker was, deep down, neither very versed on matters of policy nor intensely interested in them. As long as it was directionally sound, he was satisfied.” …

It was a classic Baker solution to the problem. As a negotiator, he always looked for ways to satisfy his counterparts’ concerns—or more precisely, ways to let his counterparts publicly demonstrate that their concerns had been addressed—without giving up the substance of what he was trying to secure.

The answers to my questions about how he rose in the Reagan administration were that he was extremely hard working, practical, canny. Reagan advisors Stuart Spencer and Michael Deaver recognized his talent and needed someone to stop a potential civil war among the Reagan team. They convinced Nancy Reagan JAB III was the guy. JAB III would be quick to say Ronald Reagan made his own decisions, but it wouldn’t’ve gotten to Ronald Reagan without Nancy Reagan.

One of JAB III’s main goals as Reagan’s chief of staff was to stop the yahoos around Reagan from getting the US involved in a war in Central America. He succeeded (mostly). Iran-Contra might’ve been avoided if JAB III hadn’t switched jobs, and gone to run the Treasury Department. Iran-Contra was sloppy and JAB III did not tolerate that. He was a scary but admired boss.

He was rich, but not as rich as people thought. When on vacation, he could usually be found shooting quail in South Texas or fishing the Silver Creek near his ranch in Wyoming. He kept a bottle of Chivas Regal in a desk drawer for an afternoon drink when needed. He swore profusely and told dirty jokes. “Did you get laid last night?” he would ask his young advance man, Ed Rogers, each morning when they were on the road together during the Reagan years. It was not a throwaway line. “He’d look me in the eye and want an answer,” Rogers recalled.

When JAB III was a kid his dad (JAB II? Also JAB III?) took him elk hunting, deep in the woods. JAB III came back with the biggest elk as his trophy. You wonder if that’s the turning point. What if the boy JAB had flinched, or said “I don’t want to kill a mammal”?

JAB III had a way of not being present at the moment of blowup. When the 1987 stock crash hit he was on his way to hunt elk with the king of Sweden. He was out of Enron just at the right time. And out of the White House for Iran-Contra, maybe he saw it coming.

And so in his desire to move on and move up, Baker left Reagan with a partner manifestly ill-suited for the job, arguably a disservice to the president he had worked so hard to make successful.

He was a flop as a retail politician, losing the one statewide race he ran in. His power was tremendous. Out of spite for the Houston Chronicle for not endorsing him, he eliminated an exception to a law stopping a nonprofit institution from owning a newspaper, thus ruining Houston Chronicle’s structure (and maybe the newspaper?) More or less singlehandedly he arranged with his worldwide financial counterparts to weaken the US dollar (good for US exporters and making it easier to pay down US debt).

Baker had little interest in Asia, Africa, or South America, nor did he want to become embroiled in the turmoil in South Africa as its system of racial apartheid unraveled in the face of international protests and sanctions. He especially wanted to stay away from the Middle East and the endless failed quest for peace between Israel and the Arabs.

Actually sometimes he is interested in South America:

Sometimes, they would conjure up the other part of their life together, getting back on the tennis court or dreaming up a hunting trip. When they flew in a helicopter over Barranquilla, Colombia, in February for a summit, Baker looked out the window at the landscape below and said to Bush, “This is a place where you and I could shoot some quail.”

In 2000 Baker led W’s legal team in the recount battle. Baker is played (well) by Tom Wilkinson in the film Recount. Ted Cruz was the guy who read the final Supreme Court decision in Bush v. Gore and translated: we win. Brett Kavanaugh was also there.

Baker doesn’t talk down W to these biographers but the ultimate results cannot have been to his satisfaction. Perhaps he tells himself the alternative, a Gore presidency, would’ve been worse. I don’t know. The W administration cannot be said to have ended in US triumph. Not enough JAB III or his ilk? Too much? A lesser grade? JAB III’s patron Cheney was there. JAB III was considered to replace Rumsfeld as Secretary of Defense. Didn’t happen: remember, he’s never there when it blows up.

As this book begins, Baker is considering Trump:

In the end, he voted for him.

A lesson here may be that forceful, smart people may have the illusion they can bend history but the consequences of both their ways and means are unpredictable.

Not sure how actionable a book like this is:

“This is not a man who sat back and read Machiavelli or read the great books about influence and power,” noted David Gergen. “It just came naturally to him.”

But it gives you the feeling of a little more understanding of the workings of the world.

You can also read, for free, online, JAB III’s oral histories with the Miller Center. Even the way he lays out the ground rules in the 2004 interview shows you what you’re dealing with. And the role of Dick Cheney in the rise of JAB comes through too.

Knott

There were some reports—not to get back to Edmund Morris—that the President was never quite the same after this assassination attempt. Did you see any change?

Baker

No. No. President Reagan had a very private but very deep spiritual faith. Remember he said, “I decided after that, that whatever time I had left, I was going to devote to the man upstairs.” Or “He spared me.” I saw that. I saw that reflective spirituality component of his personality, but that’s all. In terms of being less vibrant, less vigorous, less effective? No, I didn’t see it. Ask Fritz Mondale if you think he was adversely affected. [laughter] He wasn’t. That was a blowout election.

* if there’s a flaw in this book, it could’ve used more about Baker’s work in Western Sahara, which apparently ended in frustration when Morocco refused to budge. Maybe that was still ongoing at press time.

The rattlesnake game

Posted: April 22, 2023 Filed under: Texas Leave a commentOne day a man walked in the saloon carrying a big glass jar with a live rattlesnake in it. He wanted to sell it. Frank says: “Hell, no, they see snakes soon enough.”

But the man kept arguing with him. He says: “It’s big money for you if you’ll buy it. Now I’ll bet the drinks for the house there ain’t a man here that can hold his finger on that glass and keep it there when the snake strikes.”

To show you what a bonehead I was, I took him up. It was thick glass and I knew damn well the snake couldn’t bite me, so I put my finger on it. The snake struck, and away come my finger. Igot mad and made up my mind I would hold my finger on that glass or bust. It cost me seventeen dollars before I quit, but since then I’ve never bucked the other fellow’s game and it has saved me a lot of money.

Frank bought the snake and he sure made money on it. It was lots of fun to get some sucker that thought he was long on nerve to go against it; no one ever could. But one night a bunch of cowboys came in and I knew some of them. They all tried the snake and failed, and one of them got mad and busted the glass with his sixshooter, and the snake got out and they had to kill it.

that from an excerpt from We Pointed Them North by E. C. Abbott, “Teddy Blue.” In his In A Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas Larry McMurtry says:

Anticipating a road trip to the northern plains I’ve been reading up. I’m good as long as I have a coming road trip to think about.

Austin and Houston (conclusion)

Posted: September 11, 2022 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

It’s a fool who wanders into Texas history unarmed

as I once saw scribbled on a bathroom stall in Terlingua. But wander I did, with my posts on Stephen Austin and Sam Houston. The goal: to recount the compelling tale of two frenemies with differing personalities who each ended up with a dynamic and glorious American city named after themselves. My stories were based on reading James L. Haley’s Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas. But soon I was lost in the mesquite thicket of Texas history. I ended up having to read a few more books to resolve questions like did Austin meet Santa Anna personally when he was in Mexico City? (Yes). Now I will attempt to conclude the story of Austin and Houston:

When we last left Stephen Austin, he’d gone down to Mexico City to appeal for relief of some grievances experienced by the mostly American-born settlers of Texas. One goal was to have Texas become its own Mexican state, instead of part of Coahuila. Austin still felt the best bet for Texas was to remain a loyal part of Mexico.

After the messes of 1832, the man left standing in power in Mexico City was a military man. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. When Stephen Austin made his pitch, Santa Anna was cool with some of the ideas, but not with Texas becoming his own state: it wasn’t big enough yet. Still, Austin felt like he’d made some progress.

On his way back to Texas in January, 1834, Austin was surprised to be arrested. Though most Mexican officials liked him, he’d apparently pissed off the vice-president, Gómez Faría. Or maybe Santa Anna had turned on him and decided he was too dangerous. Austin was taken to a prison in Mexico City: he could order wine and cheese brought in from outside, but he was horribly bored because he wasn’t allowed any reading materials. He tamed a prison mouse as his friend. Eventually he got a French language history of Spain’s Philip II to read. Perhaps he read it aloud to his mouse.

Finally, on Christmas Eve, 1834, Austin was let out of prison. Imagine our hero, walking the streets of Mexico City, a free man, pondering the future.

Santa Anna ended up as more or less dictator of Mexico and he led a brutal campaign suppressing a rebellion in Zacatecas: maybe two thousand civilians were killed. Austin probably heard about this in New Orleans, where he’d gone on a visit, and where the future of Texas was a hot top. Sailing from New Orleans to Brazoria, Texas, Austin witnessed a Mexican ship exchanging shots with an American ship and a Texas steamboat (the Laura). Put ashore at Velasco, Austin stayed at the house of friend, and took a long walk on the beach that night. At a welcome dinner for him back in Brazoria, Austin proposed a toast:

The constitutional rights and the security of peace of Texas – they ought to be maintained, and jeopardized as they now are, they demand a general consultation of the people.

Doesn’t really seem that rousing: Austin did tend toward caution. But soon he threw in with the War Party in Texas. A Mexican army was coming, reconciliation no longer seemed possible. In the town of Gonzales, the American settlers had a cannon. When a Mexican army colonel came down from San Antonio, the locals put up their “COME AND TAKE IT” flag.

Volunteers came down to Gonzales. Austin arrived on the scene and was elected commander in chief of the “Army of the People.”

All sorts of goons and roughnecks turned up to join the fight. Jim Bowie, already famous for his special knife and for killing a guy during the Sandbar Fight over in Louisiana, and Deaf Smith, and quite a few Tejanos, like Juan Seguin. And finally, Sam Houston.

This small Texan army moved towards San Antonio. Austin’s biggest problem was that everyone was drunk all the time.

In the name of Almighty God send no more ardent spirits to this camp – if any is on the road turn it back

Austin led the volunteers by democracy, which was not an effective method, but may have been the only one anyone would accept. Austin wanted to attack the Mexican troops at San Antonio while they had a good chance. But when he tried to order it, the volunteers basically responded with “nah.” That was the end of Austin as commander. The Texas Consultation that was providing a loose organization instead gave him the job of commissioner to the US. He’d go to give speeches, raise money and support for Texas. This was a much better fit for his talents. The head of the army job went to Sam Houston.

The state of affairs in Texas at this point was a mess. The Texas Consultation at this point still hadn’t declared independence. All sorts of violent and random maniacs were arriving, some of them getting themselves killed in ill-conceived attacks on Mexican outposts. Houston sent a few of these guys, including Bowie and William Travis, to San Antonio with the suggestion that they blow up the Alamo mission building and then retreat. Instead, as Haley puts it:

the nonmilitary yahoos, still enjoying the freedom of the city, preferred to spend their time in the cantinas listening to the legendary Bowie tell his stories.

Haley notes about Bowie:

weakened by long and superhuman alcohol consumption, he fell into a lethal delirium of pneumonia and probably diphtheria and was not a factor thereafter

(I really recommend Haley’s chapter on the Alamo, “Brilliant. Pointless. Pyhrric.”)

Travis did his best to get a defense organized, but Santa Anna and some six thousand troops and twenty cannons quickly got the place surrounded and killed everybody. Another branch of Houston’s army, four hundred or so guys under James Fannin, were surrounded at Goliad. Again the Mexicans killed everybody.

Houston, sensibly enough, decided to retreat. This retreat, the Runaway Scrape, was not easy or happy or well-organized. Houston struggled to keep things organized, he’d be fighting with guys who wouldn’t move until they’d had breakfast, stuff like that. The Texas Convention nearly took away Houston’s command. But Houston did manage to hold about a thousand guys together, retreating, retreating, retreating. Until suddenly they turned around and attacked.

Some of the Texian army had captured a Mexican soldier who revealed that Santa Anna’s force was not as large as they’d thought. Houston gave everybody a “remember the Alamo!” speech and they went for it, and won.

Whether Santa Anna was surprised at San Jacinto because he was busy at the time with Emily West/Emily Morgan, “the Yellow Rose of Texas,” born a free woman of color in Connecticut, recently kidnapped by Mexican soldiers, is beyond the scope of this post. Houston apparently did tell someone years later that Santa Anna was with a woman at the time of the attack. One way or another, Houston’s army caught the Mexicans literally napping. Most importantly, they captured Santa Anna personally.

Around the one hundredth anniversary, on the site of the battlefield, Texas built an insanely tall, almost Stalinist style monument.

While crazy, the scale and grandeur is kind of appropriate to how decisive the San Jacinto battle was. Imagine if Robert E. Lee had been captured at Gettysburg (or, more like, if Lee and Jefferson Davis were one guy, who then got captured at Gettysburg). If history followed the pattern of the previous year, it seems much more likely the Texian army would eventually be captured by the Mexicans, everybody massacred once again. Maybe the US would’ve gotten involved, but it’s possible Santa Anna would’ve pacified Texas and retaken it forever.

Instead, in a short engagement the war for Texas independence was won, though the participants didn’t realize it yet. It’s kind of surprising that the Texans didn’t execute Santa Anna, as many wanted to. Instead Houston used Santa Anna to order his army away. Eventually the Mexican dictator was sent back to Mexico by way of Washington.

Austin heard the news of San Jacinto in New Orleans. He quickly bought a bunch of food, which he knew the Texans would need, having abandoned their farms and ranches in the Runaway Scrape. Austin hurried home to expected glory.

I have been nominated by many persons whose opinions I am bound to respect, as a candidate for the office of President of Texas

Austin said in a statement, concluding that he would serve if he won. An election was held. When the votes came in Sam Houston got 5,119, and Austin got 586.

This really hurt Austin’s feelings. He hadn’t even come in second. Apparently Austin believed Houston had once promised him he’d never run for president of Texas, so he felt betrayed, in addition to being disappointed that his countrymen hadn’t recognized all he’d done for them.

A successful military chieftain is hailed with admiration and applause, but the bloodless pioneer of the wilderness, like the corn and cotton he causes to spring where it never grew before, attracts no notice…

Austin wrote in a self-pitying letter to his cousin.

Houston appointed Stephen Austin as secretary of state of the Texas Republic. Living in a back room in Columbia, Texas, the new capital, Austin caught a cold in December, 1836. It turned into pneumonia. on December 27th, he woke up, and declared “The independence of Texas is recognized! Don’t you see it in the papers? Doctor Archer told me so!” Then he fell back asleep, and thirty minutes later he died. He was forty-three.

When Sam Houston heard the news, he issued a proclamation:

The Father of Texas is no more! The first pioneer of the wilderness has departed.

They were both pretty dramatic guys.

Houston would live on for a long time. Once Texas became a state, he served as a US senator. He was serving as governor of Texas in 1861 when the state voted to join the Confederacy. Houston thought this was a bad idea, and refused to swear an oath to the Confederacy, so the legislature declared him no longer governor. He warned the Texas about the north:

They are not a fiery, impulsive people as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche; and what I fear is, they will overwhelm the South.

Houston moved to this odd looking house, and died in 1863.

Around 1835, two real estate speculators, the Allen brothers, laid out an idea for a city not far from San Jacinto. They named it after the first president of the Republic of Texas. In 1837, Houston was incorporated. Houston was briefly the capital of Texas, but a few years later, a site for a new capital was selected. First called “Waterloo,” it was soon renamed in honor of Stephen Austin.

In his essay “A Handful Of Roses,” collected in In A Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas, Larry McMurty depicts Houston (this is 1966) as a city of beer bars and shootings, “lively, open and violent,” and Austin as a city whose most characteristic activity is “the attempt to acquire power through knowledge.” He says Austin is the one town in Texas where there’s “a real tolerance of the intellectual.” In some ways the two cities do seem to bear some of the color of their namesakes, but maybe that’s just coincidence, or the human desire to see connections everywhere.

Next time I’m in Brazoria County I’d like to see this statue of Austin:

Thus concludes the story of two guys.

(My sources for this, beyond Haley’s Passionate Nation, include T. H. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star: A History of Texas and The Texans, and Stephen F. Austin: Empresario of Texas by Gregg Cantrell)

Austin and Houston, Part Two

Posted: May 19, 2022 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment(working out the history on these two, here is part one)

Sam Houston moved from Virginia to Tennessee with his widowed mother when he was thirteen, in 1806. Imagine what Virginia was like, let alone Tennessee, in 1806. At sixteen, Sam ran away and lived with the Cherokee Indians. He learned to speak their language, hunted with them in the woods. At age twenty he fought with the US Army in the War of 1812. Fighting Creek Indians under Andrew Jackson, he was wounded three times, and got his commander’s attention.

As part of Jackson’s political machine slash semi-dictatorship of Tennessee, Houston served two terms in Congress, then became governor. However, when his wife, Eliza Allen, left him after two months, Sam resigned as governor, went to live with the Cherokee again, took a Cherokee wife, got malaria, and become such an alcoholic mess that the Cherokee nicknamed him something like “Big Drunk” (or maybe it was like “Drunk Clown,” would love to hear from any Cherokee speakers/translators.)

On a mission to Washington for the Cherokee, Sam Houston beat up an Ohio congressman and was put on trial and convicted. (Francis Scott Key was his lawyer). The whole incident turned out to be good for Houston’s reputation, at least around Andrew Jackson’s crew, a rowdy bunch. Jackson welcomed Houston back into his circle.

Andrew Jackson hated the British. As a boy, Jackson had been captured by the British. The British had killed two of his brothers, and contributed to the death of his mother. Jackson was worried his enemy Britain might get their hands on Texas from the newly independent, and quite unstable, Mexico. The US had tried and failed to buy Texas from Mexico, and were left unsatisified.

Jackson decided to send Sam Houston down to Texas. “Stir up a rebellion, create opportunities for the US take this territory,” might’ve been the instruction. I don’t know, I wasn’t there.

Down in Mexico City, the capitol of newly free Mexico, there had been instability. Coups, counter-coups. During the uncertainty, the American settlers of Texas had pulled together two conventions, with the idea of trying to separate from the state of Coahuilla. To get Texas as its own (Mexican) state. The Texans felt underrepresented in the state legislature, plus the capital in Saltillo was too far away.

The conventions agreed to petition for statehood. The man appointed to take the results down to Mexico City was Stephen Austin.

Sam Houston, meanwhile, had arrived in Texas.

Part three to come.

(source on that photo, most of my info here coming from James L. Haley’s Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas).

Austin and Houston

Posted: May 6, 2022 Filed under: Texas Leave a commentStephen Austin’s father Moses, who knew something about lead mining, got a contract to roof the Virginia legislature building with lead. But he lost money on the deal and ended up almost broke.

The Austin family wandered into what was then Spanish territory in what’s now Missouri. Spanish and French claims in this area went back and forth during Napoleonic tumult in Europe. While the Austins were in [now] Missouri, Napoleon ended up with it. Napoleon needed money to fund various losses, including slaves taking over what’s now Haiti, so he sold these lands to Thomas Jefferson in the Louisiana Purchase, and the Austins became US citizens again.

(TJ and Napoleon making a real estate deal. James Madison and marquis de Barbé-Marbois doing the agenting. Is that not one of the best dealmaking stories of all time?)

Young Stephen Austin was sent to boarding school in Connecticut and then college in Kentucky.

During his lonely years in boarding school, which he loathed, every letter from his father, which he tore open in a search for encouragement and affection, badgered him about how to become a great man.*

Meanwhile Moses Austin went broke again. His education complete, Stephen Austin left the family and became a judge in Arkansas.

Moses got the idea to head down to Texas, in what was then Spanish Mexico. He’d once been a Spanish citizen after all. Moses went to visit his son Stephen, who, though he was struggling himself, lent his dad fifty dollars, a horse, and a slave named Richmond.

A few years later, Stephen was in New Orleans. He wasn’t prospering. His dad wrote to him from Texas, and Stephen decided to join him. By the time he got to the town of San Antonio, Stephen learned Mexico had declared independence and was now a new nation. He was no longer in Spanish territory but in the Mexican state of Coahuilla-Tejas.

Stephen Austin conceived of a real estate scheme. He would become a developer. He would get land granted from Mexico and give it to Americans who would move to Tejas. Stephen taught himself Spanish out of a book and went to Mexico City to work out a contract. He got an amazing deal: he was offered 783,757 acres to distribute to 300 families. The head of each family would get 4,428 acres for ranching and 177 acres from farming.

The native Karankawa people had no say in any of this. Austin claimed these people were cannibals and should be killed on sight. He hired ten seasoned fighters and made them into a company that would ride the range. This unit is sometimes considered the first version of the Texas Rangers.

At first Austin could sort of control who came to his colony. But it got out of hand. The area between the Sabine River and the Neches, “the Neutral Ground,” had never been under the control of any government, falling between Spanish, American, and French claims. This area had become a lawless wilderness zone, a notorious hideout for murderers, convicts, outlaws, desperados of all types. Some of that element came into Austin’s zone. So too did the desperate or the ambitious from Tennessee, Louisiana, elsewhere. The word on Texas was out. “Going to Texas” became kind of a mania in the United States.

The government of Mexico tried to get a grip. They passed the Law of April 6, 1830, which banned any new American immigration into Mexican territory, including Texas (and what’s now California). The law also banned the importing of slaves into Mexico. Austin, who had good relationships in Mexico City, managed to get an exemption on this one.

It was around this time that Sam Houston showed up.

Part two to follow.

* source for that quote and much of this info James L. Haley’s Passionate Nation: The Epic History Of Texas

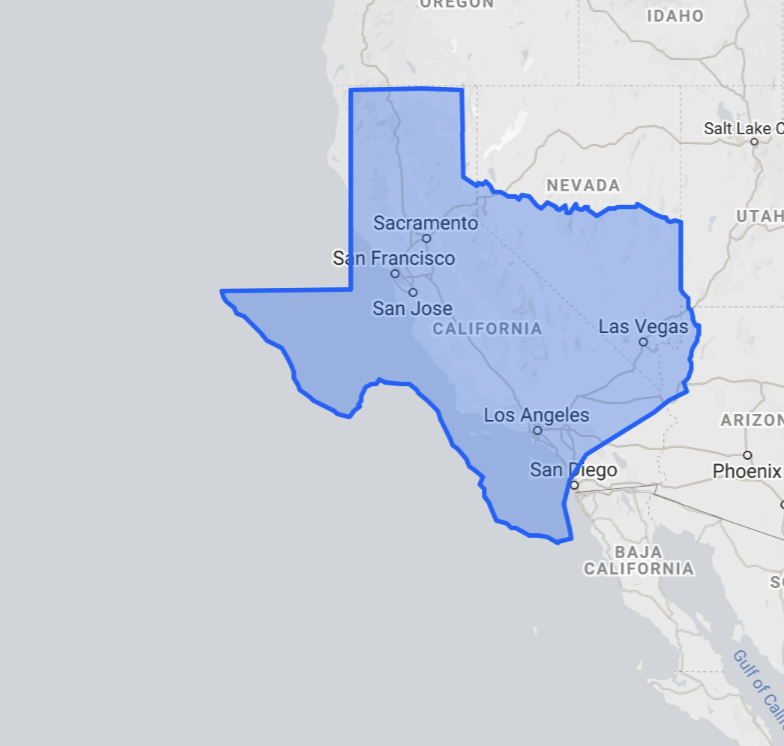

Texifornia

Posted: February 22, 2022 Filed under: California, Texas Leave a commentInspired by the shirt the crew wears at Bludso’s BBQ decided to compare. How big is California compared to Texas?

And just for a laugh:

True Size Of... is the tool used for that.

Dublin Dr. Pepper

Posted: January 25, 2022 Filed under: beverages, Texas Leave a commentThe town is the former home of the world’s oldest Dr Pepper bottling plant (see Dublin Dr Pepper). The plant was for many years the only U.S. source for Dr Pepper made with real cane sugar (from Texas-based Imperial Sugar), instead of less expensive high fructose corn syrup. Contractual requirements limited the plant’s distribution range to a 40-mile (64 km) radius of Dublin, an area encompassing Stephenville, Tolar, Comanche and Hico.

Was looking up some of the towns where various pro bull riding stars are from: Jesse Petri hails from Dublin, TX. My goodness I’d like to try that Dublin Dr. Pepper.

from the Dallas Morning News, March 31, 2017:

Ask for a Dr Pepper, and the response was routine and coy: “We don’t have a knock-off Dr Pepper, but you ought to try our Dublin Original. It’s really good, and I know you’ll love it.”

Kloster said it was a conscious marketing decision to offer customers who loved Dr Pepper a nostalgic product that looked and tasted similar. Even the bottle was packaged with stripes from a retro Dr Pepper color scheme and a “DDP” on the label.

“It got out of hand. We got out there and we pushed the envelope,” Kloster said. “The Dublin Original black cherry was pushing the envelope and was in violation of the agreement.”

boldface mine.

Dr. Pepper Snapple Group has since been consumed by Keurig Dr Pepper. I don’t expect any sense could be talked into the people who think shooting hot water through plastic is a good method of making coffee, but if I can find the time perhaps I’ll reach out to the JAB Group.

What if it turned out life expectancy in Stephenville, Tolar, Comanche and Hico had been 135 years + back in the sugar age?

South Louisiana Light Sweet

Posted: April 20, 2020 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

Today was a good day for learning the names of types of crude oil. Source.

Maine and Texas

Posted: September 17, 2019 Filed under: America Since 1945, food, New England, Texas Leave a comment

This one came up on Succession, a fave show. (Had to look it up because I wondered if they were doing a double joke where the guy was attributing Emerson to Thoreau)

Usually I’ll approach with tentative openness the pastoralist, simpler times, “trad” adjacent arguments of weirdbeards but Thoreau here WAY off. Maine and Texas had TONS to communicate! Who isn’t happy Maine and Texas can check in? (Saying this as a Maine fan whose wife is from Texas, fond of both states and happy for their commerce and exchange). Plus, if Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough, I WANT to hear that, that’s interesting goss!

The “broad flapping American ear” there — a snooty New England/aristocrat attitude we haven’t heard the last of. These guys are the original elites. There’s really two classes in America: Americans, and The People Who Think They’re Better Than Americans. Though they’re a tiny minority the second group wields outside power and influence over the first group. I’m a proud member of the first group though I admit I have second group tendencies due to my youthful indoctrination in the headquarters of these Concord Extremist Radicals, in fact at their head madrassa.

When you hear America assessed by Better Thans / eggheads, wait for the feint toward fatshaming. It’s always in there somewhere. American Better Thans adopted this from Europeans, whom they slavishly ape. It’s a twisted attitude, designed to take blame away from the Better Thans and their friends in the ownership.

As if it’s Americans fault that they’ve been raised associating corn-based treats with love and goodness! Or that corn-fatted meat is the easiest accessed protein on offer! You think that’s more the Americans fault, or the fault of the Better Thans, who manipulate our food system with their only goal creating shareholder value?

Is it the fault of the American that a cold soda is the best cheap pleasure in the hot and dusty interior where they don’t all have Walden Pond as a personal spa?

Thoreau. Guy makes me sick.

In researching this article I learn about Maine-ly Sandwiches, of Houston.

Adobe Walls

Posted: December 30, 2018 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

Best as I can tell both the first and second Battles of Adobe Walls happened somewhere around here, near what’s now Stinnett, Texas, founded 1926 by A. P. Ace Borger.

That’s from

which I’m finding fantastic. I’m not THAT into The Searchers the movie (I mean I think it’s cool) but this book is amazing as Texas history. I’d put it on a shelf with God Save Texas by Lawrence Wright. They can split the Helytimes J. Frank Dobie Texas History Prize for 2018.

photographer unknown.

A Kiowa ledger drawing possibly depicting the Buffalo Wallow Battle in 1874, one of several clashes between Southern Plains Indians and the U.S. Army during the Red River War.

Billy Dixon was there:

Billy Dixon during his days as an Indian scout. Only known picture of him while he still wore his hair long as he did during his Indian fights.

By August a troop of cavalry made it to Adobe Walls, under Lt. Frank D. Baldwin, with Masterson and Dixon as scouts, where a dozen men were still holed up.[1]:247 “Some mischievous fellow had stuck an Indian’s skull on each post of the corral gate.”[1]:248 The killing had not ended, however; one civilian was lanced by Indians while looking for wild plums along the Canadian River.

This wasn’t that long ago.

Maybe some day I’ll get to that part of Texas. Long Texas drives have formed an important part of my life. Wouldn’t have it any other way.

God Save Texas by Lawrence Wright

Posted: August 18, 2018 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

a spontaneous Helytimes Book Prize For Excellence is awarded to God Save Texas by Lawrence Wright. Absolutely fantastic. The Alamo, Marfa, Willie Nelson, Ann Richards, how the legislature works, the Kennedy assassination, Spindletop, everything you’d want to read about in a book about Texas is succinctly, thoughtfully, humorously explored.

Two clips:

What?! and:

A special bonus: this book has a firsthand account of the 1999 Matthew McConaughey “bongos incident.”

Advances in Cormac studies

Posted: April 9, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, Texas, writing Leave a comment

Morrow quotes McCarthy as saying that “even people who write well can’t write novels… They assume another sort of voice and a weird, affected kind of style. They think, ‘O now I’m writing a novel,’ and something happens. They write really good essays… but goddamn, the minute they start writing a novel they go crazy“

In early 2008 Texas State University announced they’d acquired Cormac McCarthy’s papers. The next year they made them available to scholars. Now two books based on rummaging around in these notes have appeared.

This one, by Michael Lynn Crews, explores the literary influences McCarthy drew on, which authors and books he had quotes from buried in his papers.

The quote about novelists going crazy is from a letter exchange McCarthy was having re: Ron Hanson’s novel Desperadoes, which McCarthy admired.

This one, by Daniel Robert King, takes more of a semi-biographical approach, tracing out what we can learn about McCarthy from his correspondence with agents and editors. A sample:

Bought these books because it gives confidence to observe that somebody whose writing sounds like it emerged pronounced from the cliffs like some kind of Texas Quran had to work and revise and toss stuff and chisel to get there.

From these books it is clear:

- McCarthy is a meticulous and patient rewriter

- it took decades for his work to gain any significant recognition

- he was helped with seeming love and care by editor Albert Erskine.

- he was patient, open, yet confident in editorial correspondence

These books are not necessary for the casual personal library, but if you enjoy gnawing on literary scraps, recommend them both. From King:

However, in this same letter, he acknowledges that “the truth is that the historical material is really – to me – little more than a framework upon which to hang a dramatic inquiry into the nature of destiny and history and the uses of reason and knowledge and the nature of evil and all these sorts of things which have plagued folks since there were folks.”

In A Narrow Grave

Posted: January 28, 2018 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

In anticipation of a trip to Texas, I got this one off the shelf. Neither McMurtry’s best (that would be Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, in which he gives a recipe for lime Dr. Pepper) or his worst (that would be Paradise, where he proves his point that Tahiti is boring), in this fan’s opinion.

McMurtry’s essay on the sexual attitudes of the post-frontier Texas of his youth is pretty interesting:

He also says it wasn’t a big deal in his youth for a young man to have sex with a cow or pig.

Good picture

Posted: September 8, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, Texas Leave a comment

Found this picture on Thomas Ricks’ blog. USA! USA!

170831-N-KL846-150 VIDOR, Texas (Aug. 31, 2017) Naval Aircrewman (Helicopter) 2nd Class Jansen Schamp, a native of Denver, Colorado and assigned to the Dragon Whales of Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 28, rescues two dogs at Pine Forrest Elementary School, a shelter that required evacuation after flood waters from Hurricane Harvey reached its grounds. The mission resulted in the rescue of seven adults, seven children and four dogs. (U.S. Navy Video by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Christopher Lindahl/Released)

Reminded of a claim that Goebbels was forever frustrated the Nazis couldn’t make propaganda as good as what the USA churned out.

Worth signing up or whatever you need to do to read Ricks’ blog.

Here’s a good post about the situation in Afghanistan.

Here’s a good one about “15 assumptions about the behavior of North Korea’s Kim family regime”

And his reliefs and suspensions specials never fail to have one or two that would probably make a compelling movie. At a secret Air Force base in Tunisia, a beloved commander lets his guys drink as much as they want and forms a dangerous relationship with a teenage subordinate.

Robert Caro’s two hour audiobook

Posted: May 19, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, New York, politics, presidents, Texas Leave a comment

Strong endorse to an audio only, 1 hour 42 minute semi-memoir by Robert Caro, boiling down the central ideas of The Power Broker and the LBJ series. If you’ve read every single extant interview with Robert Caro, as I have, some of its repetitive but I loved it and loved listening to Caro’s weird New York accent.

Two details: he tells how James Rowe, an aide to FDR, told him that FDR was such a genius about politics that when he discussed it almost no one could even understand him. But Lyndon Johnson understood everything.

James Rowe, from the LOC

Caro tells that when LBJ ran for Congress the first time, he promised to bring electricity. Women had to haul water from the well with a rope. A full bucket of water was heavy. Women would become bent, a Hill Country term for stooped over. LBJ campaigned saying, if you vote for me, you won’t be bent. You won’t look at forty the way your mother looked at forty.

from the Austin American Statesman collection at the LBJ Library. The woman’s name is Mrs. Mattie Malone.