Tom Stoppard

Posted: December 6, 2025 Filed under: writing Leave a commentOne speech [in the play “Dirty Linen”} that gets an unfailing ovation, however, is the following tribute to the American people, paid by a senior British civil servant:

They don’t stand on ceremony. . . . They make no distinction about a man’s background, his parentage, his education. They say what they mean, and there is a vivid muscularity about the way they say it. . . . They are always the first to put their hands in their pockets. They press you to visit them in their own home the moment they meet you, and are irrepressibly good-humoured, ambitious and brimming with self-confidence in any company. Apart from all that I’ve got nothing against them.

from this 1977 New Yorker profile of Tom Stoppard by Kenneth Tynan. I used to buy used copies of Tom Stoppard plays at the Harvard Bookstore, in this way I read Arcadia, Travesties, Invention of Love, a bunch of the other ones, they’re all terrific. Salute to a real one. Since how much money writers make is always of interest:

When I asked him, not long ago, how much he thought he had earned from “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” his answer was honestly vague: “About—a hundred and fifty thousand pounds?” To the same question, his agent, Kenneth Ewing, gave me the following reply: “‘Rosencrantz’ opened in London in 1967. Huge overnight success—it stayed in the National Theatre repertory for about four years. The Broadway production ran for a year. Metro bought the screen rights for two hundred and fifty thousand dollars and paid Tom a hundred thousand to write the script, though the movie was never made. The play had a short run in Paris, with Delphine Seyrig as Gertrude, but it was quite a hit in Italy, where Rosencrantz was played by a girl. It did enormous business in Germany and Scandinavia and—oddly enough—Japan. On top of that, the book sold more than six hundred thousand copies in the English language alone. Up to now, out of ‘Rosencrantz’ I would guess that Tom had grossed well over three hundred thousand pounds.”

That’s in 1977!

Finish drafts

Posted: October 24, 2025 Filed under: advice, writing, writing advice from other people 1 Comment

Woody Allen: NOT in fashion.

I’m interested only in his productivity. Whatever else you say about him, my guy made a lot of movies. How?:

appears in an interview from 2015 with Richard Stayton in Written By magazine.

(For the love of Buddha if you are easily triggered don’t look at the WGA’s list of 101 funniest screenplays)

Robert Coover

Posted: October 8, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, baseball, writing 1 CommentThe postmodernist Robert Coover died at 92. The Universal Baseball Association is the only one of his I’ve read. This is how the NYT describes it in Coover’s obituary:

Mr. Coover’s many other books included “The Universal Baseball Association, J. Henry Waugh, Prop.” (1968), about an accountant who invents a fantasy-baseball game and is driven mad by it

That’s accurate enough I guess. I loved reading the book. It’s the only one of Coover’s I read, and although it’s sort of fantastical, the plot’s kinda straightforward and the setting is vivid and lived-in. I went looking for the back cover copy that was on my old edition:

He eats delicatessen.

In new editions that’s updated to “take-out,” a mistake in my opinion. I remember Fener laughing out loud when he read that off the back cover when he found it in my office. The term “b-girl” was also dated by the time I read it, it seemed to mean something like this.

Spoiler below as I recall the plot:

Waugh is playing out a season of a dice based fantasy baseball game of his own invention. A star player, a wonderful pitcher, freakishly good emerges, and Henry comes to love him. Then one night he rolls the dice and can’t believe the outcome. The player is killed by a pitch. Henry can’t believe it. It shatters his world. It seems to be sort of a metaphor for God and Jesus (J. Henry Waugh/Yahweh).

The idea of going home to your own private world was on my mind at the time I read the book, when I was a young single man in LA, I’d leave work at 6pm or whatever and walk home to my one bedroom apartment and read or work on writing scripts or novels. It spoke to me, and what spoke to me about it wasn’t the postmodernism (in fact the metaphorical stuff kinda made me roll my eyes) but the realism, the portrait of a life, the investment and absorption into a private entertainment, the sadness and loss of having the game shattered.

So, salute to Robert Coover.

Eleven pages a week

Posted: August 24, 2024 Filed under: Hollywood, the California Condition, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

In one of my Hollywood books I read that writers in the studio system were expected to write eleven pages a week.

Eleven pages, seems very reasonable. Especially if we are talking script pages which have a lot of white on them.

Now you may have to write thirty-three pages to produce eleven good ones, but still.

I went looking for where I found this information but I couldn’t locate it in Schatz, Genius of the System, or Friedfrich, City of Nets, or Thomson, The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood, or Behlmer, Memo from David O. Selznick, or Pirie, Anatomy of the Movies, or Rosen, Hollywood, or Dardis, Some Time in the Sun, or Powdermaker, Hollywood: The Dream Factory or even Solomon, William Faulkner The Screenwriter. Not to say it’s in one of those, I just couldn’t retrieve it.

Using a Google Books search I did find reference to an eleven pages expectation:

That’s in Mark Wheeler, Hollywood: Politics and Society, which I’ve never read.

Cool cover!

If you reliably produce eleven pages a week your odds at some success are high.

Eleven pages a week will be my goal when I return from vacation at the end of August.

(that Faulkner typing pic seems to be from Time-Life Getty Images, found it on Reddit).

Paul’s Case by Willa Cather

Posted: August 17, 2024 Filed under: writing Leave a commentNew York has certainly inspired its share of coming-to-the-city adventures. One of the most striking is a short story by Willa Cather called “Paul’s Case,” which first appeared in The Troll Garden in 1905. Paul, a high school student in Pittsburgh, is gawky and awkward, with a “certain hysterical brilliancy” in his eyes. A fantasist and a dreamer, he is hopelessly out of sync with the life around him—but he has neither the graces nor the gifts that might enable him to escape from the constricting middle class life on suburban Cordelia Street, where he lives with his father, a widower, and there is nothing but “the loathing of respectable beds, of common food, of a home permeated by kitchen odours.” Paul comes alive only in the evenings, when he works as an usher at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Hall, wears a uniform that makes him feel handsome, guides elegant people to their seats, and listens to the music and experiences a “zest for life.” Paul is not exactly a music lover; it’s the enveloping glamour of the theater that holds him. He loves to visit backstage with the artists; “the stage entrance of the theater was for Paul the actual portal of Romance.”

But Paul’s father, a dim figure constantly urging on his son the example of more enterprising young men, becomes increasingly enraged by his son’s behavior. He pulls him out of the school he barely seems to be attending, forbids the theater to employ him or to let him through the door, and puts him to work at the offices of Denny & Carson. And suddenly Cather jumps forward, to Paul sitting on a train. He has stolen a thousand dollars in cash that he was supposed to deposit in the bank for his employer, and he is on his way to New York.

Arriving in the city, Paul buys expensive clothes, fine luggage, “silver mounted brushes and a scarf-pin” at Tiffany’s. He takes a luxurious suite at the Waldorf, and for a few days he exults in his sitting room, which he fills with flowers, in the perfectly appointed bathroom, in the elegance of the hotel dining room, in carriage rides up Fifth Avenue. He knows that it will only be a matter of days before his crime is discovered and he is tracked down. All over New York, the snow is falling. Paul’s “chief greediness,” Cather writes, “lay in his ears and eyes, and his excesses were not offensive ones. His dearest pleasures were the gray winter twilights in his sitting-room; his quiet enjoyment of his flowers, his clothes, his wide divan, his cigarette and his sense of power.” As soon as he “entered the dining-room and caught the measure of the music,” he was “lightened by his old elastic power of claiming the moment, mounting with it, and finding it all sufficient.” He exults in “the glare and glitter about him.” He is cosseted in a magical world. And when he is down to his last hundred dollars, he knows the game is up. He leaves New York, lies down on a train track in New Jersey, and lets the end come.

In Cather’s story, New York is less a place that a person can actually inhabit than a kind of luxurious illusionist’s trick, centering on the Waldorf and the city avenues, and united by the snow that softens the views out the windows and carpets everything. In “Paul’s Case” New York is not a living city so much as it is a fantasy, a stage set.

from this great 2001 essay, “The Adolescent City,” by Jed Perl.

The pages in Balzac’s Lost Illusions in which the young writer Lucien Chardon comes to Paris and wanders through the overwhelming elegance of the city constitute one of the greatest descriptions in all of literature of the tidal pull of urban life, with its intoxicating strangeness. Visual artists have generally shied away from such a theme, which necessitates unfolding, multiplying revelations, though there are a few exceptions, the greatest of which is probably Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s vast City of Good Government, painted on a wall in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena in 1338-1339. Here relations between the city and the country center around the gate of Siena, where elegant aristocrats going out for a day of hunting pass country yokels coming into town with their livestock.

Scraps of time

Posted: January 1, 2024 Filed under: advice, writing Leave a comment

Douglas Southall Freeman is out of fashion these days. He was a great perpetuator the Robert E. Lee myth, simply by writing so damn much about him. His biography of Lee takes up four volumes:

and Lee’s Lieutenants (that is to say his generals) get three!:

Then again Lee already had a statue in Richmond, which Freeman saluted every day on the way to work:

Freeman’s work ethic was legendary. Throughout his life, he kept a demanding schedule that allowed him to accomplish a great deal in his two full-time careers, as a journalist and as a historian. When at home, he rose at three every morning and drove to his newspaper office, saluting Robert E. Lee’s monument on Monument Avenue as he passed. Twice daily, he walked to a nearby radio studio, where he gave news broadcasts and discussed the day’s news. After his second broadcast, he would drive home for a short nap and lunch and then worked another five or six hours on his current historical project, with classical music, frequently the work of Joseph Haydn, playing in the background.

from the intro to this book of Freeman’s speeches:

Freeman later remarked that a statement made by [Prof. S. C. Mitchell] during a lecture on Martin Luther meant a great deal to him:

Young gentlemen, the man who wins is the man who hangs on for five minutes longer than the man who quits.

I found some advice that I’m going to make my New Year’s Resolution, boldface mine.

Know your stuff. Now that means a lot in the way of the utilization

of your time. And it means a lot in the way of utilization of a navy

wife or an army wife. You boys think you have a hard life to lead. You

don’t have any tougher life to lead than the life of a navy wife. And

both the navy husband and the navy wife need to learn all they can,

when they can. I’d like to give you a little motto on that question. I

gave it to one of my historical secretaries. She happens to be the one

who came up with me this morning. She said it was the most useful

thing I’d ever told her. It came from Oliver Wendell Holmes, a justice

of the Supreme Court of the United States, who should have been chief

justice. Holmes would get a boy from Harvard Law School every year,

and that boy would have one year as Holmes’ law clerk, a magnificent

training, out of which in their generations have come some of the best

lawyers in public service in America. And one of the favorite things

that he would tell these boys was, “Young man, make the most of the

scraps of time.” Now believe me, if you want to know your swuff and

know it better than the other man, you’ve got to spend more time on

it; and if you are going to spend more time on it, you’ve got to make

the most of the scraps of time. The difference between mediocrity and

distinction in many a professional career is the organization of your

time. Do you organize it; do you make the most of the scraps of time?

Bless my soul, I don’t suppose that the admiral, with his dignity and

justice and regard for all the amenities, says no to you about playing

bridge; but there is many a man who would have three more stripes

on his sleeve if he gave to study the time that he gives to bridge. Don’t

say that you have to have the recreation. You have to have enough

recreation, but diversification of work is the surest recreation of the

mind.

(Note: the source of this advice is Union vet/Bostonian OWH Jr., not Confederate sympathizer DSF, so we’re clean.)

Most of the speeches in this book were given in the late 1930s and early 1940s at The Army War College and the Navy War College. Freeman was conveying lessons learned in the Civil War/War of the Rebellion to the generals and admirals who would end up fighting the Second World War. Freeman’s own father had been in the Army of Northern Virginia.

In the book Freeman tells a bunch of good stories, here’s one about Jubal Early (who Freeman met many times):

Early had about him a carping, singularly bitter manner that alienated nearly every man who was

under him. Lee, if there was a doubt whether a fault was his or a subordinate’s, would always assume it; Early, never. Sometimes his wit was good. You may not be familiar with his great exchange with John

C. Breckinridge. Breckinridge had been, as you remember, a candidate for the presidency in 1860. Before that time he had been a great political leader, standing on the principle of the right of slavery in the territories. He fought with Early through a part of the Valley campaign of 1864. Early never forgot that he was a politician, though Breckinridge was a very good soldier. In a very desperate hour-I think it was at

Winchester-when Rodes had been killed and the situation was very desperate, Breckinridge was in full retreat. Early met him in the road and said, “Well, General Breckinridge, what do you think about slavery

in the territories now?”

William Faulkner’s introduction to Sanctuary

Posted: December 31, 2023 Filed under: memphis, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentThe best character William Faulkner ever created was himself, William Faulkner. The flying injury, Rowan Oak, the photographs, the guest roles, the interviews, scraps of footage, the Nobel Prize speech. Perfect.

In 1929 William Faulkner, then age 31, wrote Sanctuary, which has one of the trashiest loglines ever: Ole Miss coed Temple Drake ends up the sex slave of a gangster named Popeye. Here at Helytimes we won’t go into detail of what exactly Popeye does, we leave that to lesser publications like The Washington Post:

what interested him chiefly about this horrific event was “how all this evil flowed off her like water off a duck’s back.” In his haste to make a best seller, he crammed in all he had seen and heard about whorehouses, rapes and kidnappings.

This was a ripped from the headlines story based on a true crime case. As a Mississippi crime book complete with courtroom scenes, it’s kind of a proto-Grisham.

Sanctuary was published by Jonathan Cape in 1931. Then in 1932 the Modern Library put out a new edition with a new introduction by Faulkner. Scholars since have apparently debunked everything Faulkner claimed in this introduction as fabulations and lies but so what? In a way that makes it even better. A work of autofiction.

We couldn’t find this introduction online so we got a used copy and scanned it in, it’s out of copyright (we believe?).

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN THREE YEARS AGO. To me it is a cheap idea, because it was deliberately conceived to make money. I had been writing books for about five years, which got published and not bought. But that was all right. I was young then and hard-bellied. I had never lived among nor known people who wrote novels and stories and I suppose I did not know that people got money for them. I was not very much annoyed when publishers refused the mss. now and then. Because I was hard-gutted then. I could do a lot of things that could earn what little money I needed, thanks to my father’s un- failing kindness which supplied me with bread at need despite the outrage to his principles at having been of a bum progenitive.

Then I began to get a little soft. I could still paint houses and do carpenter work, but I got soft. I began to think about making money by writing. I began to be concerned when magazine editors turned down short stories, concerned enough to tell them that they would buy these stories later anyway, and hence why not now. Meanwhile, with one novel completed and consistently refused for two years, I had just written my guts into The Sound and the Fury though I was not aware until the book was pub- lished that I had done so, because I had done it for pleasure. I believed then that I would never be published again. I had stopped thinking of myself in publishing terms.

But when the third mss., Sartoris, was taken by a publisher and (he having refused The Sound and the Fury) it was taken by still another publisher, who warned me at the time that it would not sell, I began to think of myself again as a printed object. I began to think of books in terms of possible money. I decided I might just as well make some of it myself. I took a little time out, and speculated what a person in Mississippi would believe to be current trends, chose what I thought was the right answer and invented the most horrific tale I could imagine and wrote it in about three weeks and sent it to Smith, who had done The Sound and the Fury and who wrote me immediately. ”Good God, I can’t publish this. We’d both be in jail.” So I told Faulkner, “You’re damned. You’ll have to work now and then for the rest of your life.” That was in the summer of 1929. I got a job in the power plant, on the night shift, from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M., as a coal passer. I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheel- barrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler. About 11 o’clock the people wuuld be going to bed, and so it did not take so much steam. Then we could rest, the fireman and I. He would sit in a chair and doze. I had invented a table out of a wheel- barrow in the coal bunker, just beyond a wall from where a dynamo ran. It made a deep, constant humming noise. There was no more work to do until about 4 A.M., when we would have to clean the fires and get up steam again. On these nights, between 12 and 4, I wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks, without changing a word. I sent it to Smith and wrote him that by it I would stand or fall.

I think I had forgotten about Sanctuary, just as you might forget about anything made for an immediate purpose, which did not come off. As I Lay Dying was published and I didn’t remember the mss. of Sanctuary until Smith sent me the galieys. Then I saw that it was so terrible that there were but two things to do: tear it up or rewrite it. I thought again, “It might sell; maybe 10,000 of them will buy it.” So I tore the galleys down and rewrote the book. It had been already set up once, so I had to pay for the

privilege of rewriting it, trying to make out of it something which would not shame The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying too much and I made a fair job and I hope you will buy it and tell your friends and I hope they will buy it too.WILLIAM FAULKNER. New York, 1932.

Happy New Year to all 6,722 of our loyal readers, all over the globe.

Scialabba

Posted: November 26, 2023 Filed under: writing 1 CommentGeorge Scialabba is no wild man. A soft-spoken, introverted soul, he doesn’t drink or smoke; no alcohol, tobacco, or recreational drugs. Healthy, moderate eating (no red meat, and “a kind of cerebral Mediterranean diet”) keeps Scialabba, at age 67, lean to a degree that is downright un-American. He has never married nor fathered children, and lives alone in a one-bedroom condo he has occupied since 1980. He doesn’t play sports (“I don’t exercise — I fidget”). For 35 years, Scialabba, a Harvard College alumnus, held a low-level clerical job at his alma mater that suited his low-profile style. For the past decade, his desk has occupied a windowless basement in a large academic building.

from the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Scialabba toiled for thirty-five years at a desk job in the windowless basement of Harvard’s Center for Government and International Studies, writing book reviews in his spare time; he has much to say about the economic conditions that enable or disable the life of the mind. (A sufferer from chronic depression, Scialabba credits his union for enabling him to take several paid medical leaves. “This is one of many ways in which strong unions are a matter of life and death,” he writes in How To Be Depressed.) And yet, for Scialabba, the essence of intellectual and creative exchange remains a gift economy: “When we’re young, our souls are stirred, our spirits kindled, by a book or some other experience,” he once said, “and in time, when we’ve matured, we look to pay the debt, to pass the gift along.” Gratitude, deeply felt, enables generosity. And never has a writer of such enviable talents displayed such undiminishing patience for his reader, such evident and unpretentious pleasure in the pedagogical function of good prose.

Commentary on Scialabba often makes much of his marginal status in relation to the more glamorous—or, at least, more lucrative—centers of intellectual life. As Christopher Lydon once put it, he has “no tenure…no tank to think in, no social circle, no genius grant (yet), no seat in the opinion industry or on cable TV—‘no province, no clique, no church,’ as Whitman said of Emerson—not even a blog.” In this, there was always a note of condescension: the working-class boy from Sicilian East Boston made good (but not good enough for the academy).

That from Commonweal.

Both note that his office is “windowless.” Love that the interesting work at Harvard is coming not from a professor but from a guy who’s working as a building manager. Lee Sandlin vibes. We love an amateur.

loneliness

Posted: November 25, 2023 Filed under: actors, writing Leave a commentAll the great plays [are] about loneliness,” [Tom Hanks] says, recounting an insight delivered to him by the theatre director Vincent Dowling. “It’s about the battle we all have to be part of something big.” It was only as an adult, says Hanks, that he realised “that’s the reason I would go to the [movie] theatre by myself as an 18-year-old kid, to be exposed to that language of loneliness”.

so says Hanks having lunch with the Financial Times, free link provided for you here. Always a little disappointed when the lunch with FT guest opts for expensive bottled water instead of a nice white wine.

economics of literature

Posted: November 13, 2023 Filed under: writing Leave a commentfrom The Guardian’s profile of Andrew Wylie:

Later in their conversation, the editor worried about what to do with the latest novel by an award-winning British writer. “The modest offer you are waiting to make will be accepted, maybe with a small improvement,” Wylie told her. He suggested €6,000.

“It’s not going to work, since he only sold 900 copies of his last book,” the editor replied.

“This is the weakest argument I’ve ever heard in my life,” Wylie teased. “The flaws are transparent and resonant.” He pointed out that a publisher’s greatest profitability comes before an author earns back their advance, then he suggested €5,000.

“More like €4,000,” the editor said.

“Forty-five hundred? Done.” Wylie announced, pleased but not triumphant.

As meagre as that amount was, if the agency could make 20 such deals around the world for a writer, and earn a similar amount just in North America, a writer might, after the 15% agency fee and another 30% or so in taxes, afford to pay rent on a two-bedroom Manhattan apartment for a couple of years. How they would eat, or pay rent after two years if it took them longer than that to write their next book, was another question.

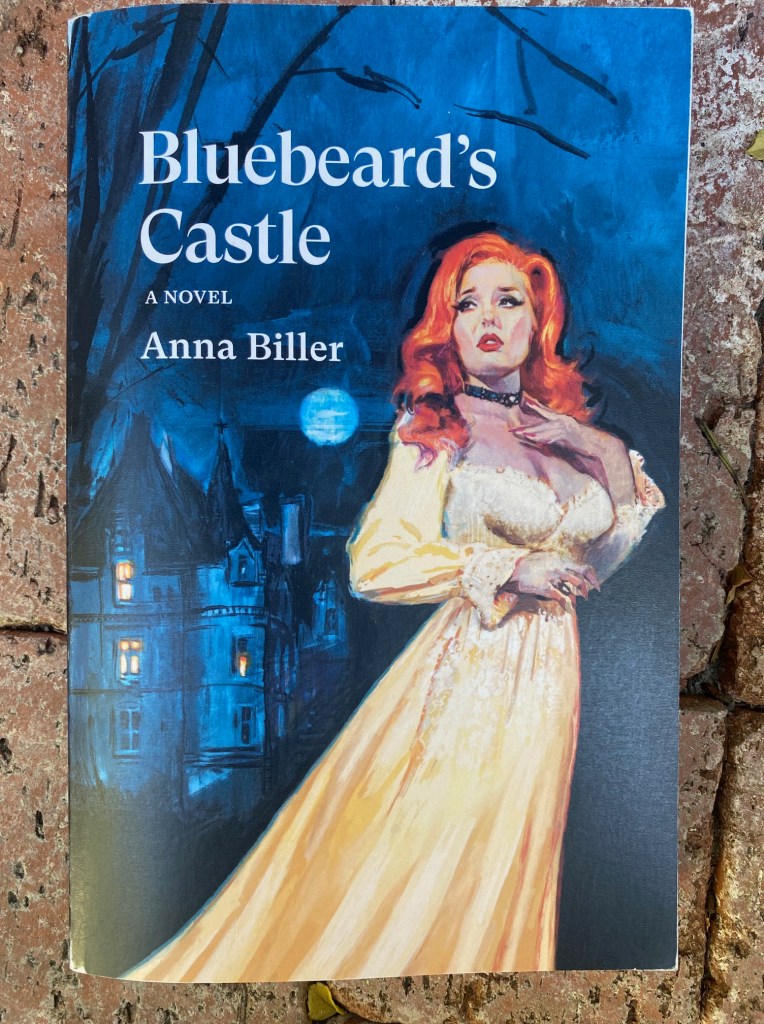

Bluebeard’s Castle by Anna Biller

Posted: September 2, 2023 Filed under: Hollywood, Steinbeck, writing Leave a comment

Anna Biller is herself an exciting, energetic book reviewer. See for example her review of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, or her other Goodreads reviews. So we’ll try to bring you the same as we review her upcoming novel, Bluebeard’s Castle.

We requested a review copy because we’re Anna Biller fans after watching the 2016 film The Love Witch. This movie can be called a cult classic. A term like that and what it says is the sort of concept Biller herself might interrogate in one of the essays on her website.

The great thing about The Love Witch is that it’s totally unique. Who else is doing this? What’s another movie like this? It’s amazing that a movie like that exists. You can feel this is a project from someone with a singular vision. The Love Witch is striking, funny, odd, with a style that’s both homage and sendup of sort of 60s-70s Vincent Price era glam horror? After seeing it we followed Anna Biller on Twitter, where she mixes it up, mostly about film, in a fun way. Really though our way in is the director’s longer pieces of writing, like this account of the awfulness of working in a Honolulu hostess bar.

Bluebeard’s Castle is exactly what it purports to be, a retelling of the Bluebeard fairy tale/story/case study. But it’s more, a kind of play on the whole idea of the gothic novel, done with enthusiasm. A striking feature of it is that while it’s specific (we learn what people eat:

) the story also plays in a dreamlike timelessness.

Very cool and thrilling, even just on the sentence level. Nothing here is as it seems.

A+, excited to see the reaction when this book is released on October 10, 2023. Great for Halloween.

Hemingway, Men At War

Posted: June 25, 2023 Filed under: Hemingway, war, writing Leave a commentonce we have a war there is only one thing to do. It must be won. For defeat brings worse things than any that can ever happen in war.

Went looking for the origin of that quote, because it seemed relevant to the current WGA strike.

The “internet of quotes” is a candy-colored jungle, where no one ever bothers to give the source or the context and half the time it’s wrong or on an inappropriate sunset backdrop.

This quote can be found in the Introduction to Men At War, by Ernest Hemingway. Men At War was a literary anthology first published in 1942. Hemingway edited his introduction for the 1955 edition. We find the whole essay reproduced here, and it’s worth a read.

The writers who were established before the war had nearly all sold out to write propaganda during it and most of them never recovered their honesty afterwards. All of their reputations steadily slumped because a writer should be of as great probity and honest as a priest of God. He is either honest or not, as a woman is either chase or note, and after on piece of dishonest writing he is never the same again.

on some pitiful bravado compared to some solid magnificence:

it was like comparing the Brooklyn Dodger fan who jumps on the field and slugs an umpire with the beautiful professional austerity of Arky Vaughan, the Brooklyn third baseman.

on Tolstoy’s War And Peace:

his ponderous and Messianic thinking was no better than many another evangelical professor of history and I learned from him to distrust my own Thinking with a capital T and to try to write truly, as straightly, as objectively and as humbly as possible.

On cavalry:

A man with a horse is never as alone as a man on foot, for a horse will take you where you cannot make your own legs go. Just as a mechanized force, not by virtue of their armor, but by the fact that they move mechanically, will advance into situations where you could put neither men nor animals; neither get them up there nor hold them there.

on fights:

At that moment it was perfectly clear that we would have to fight them.

When that moment arrives, whether it is in a barroom fight or in a war, the thing to do is to hit your opponent the first punch and hit him as hard as possible.

A couple recommendations I’ve got to check out: a story called “The Wrong Road” by Marquis James and “The Stars in Their Courses” by Lt. Col. John W. Thomason, a chapter in a book called Lone Star Preacher (did Shelby Foote crib that title title for his book on Gettysburg?)

To live properly in war, the individual eliminates all such things as potential danger. Then a thing is only bad when it is bad. It is neither bad before nor after. Cowardice, as distinguished from panic, is almost always simply a lack of ability to suspend the functioning of the imagination. Learning to suspend your imagination and live completely in the very second of the present minute with no before and no after is the greatest gift a soldier can acquire. It, naturally, is the opposite of all those gifts a writer should have. That is what makes good writing by good soldiers such a rare thing and why it is so prized when we have it.

(is that what DFW was trying to say, re athletes not soldiers, in his Tracy Austin review?)

I have seen much war in my lifetime and I hate it profoundly. But there are worse things than war: and all of them come with defeat. The more you hate war, the more you know that once you are forced into it, for whatever reason it may be, you have to win it. You have to win it and get rid of the people that made it and see that, this time, it never comes to us again.

As for Arky:

After leaving the Seals, Vaughan bought a ranch in Eagleville, California, where he retired to fish, hunt and tend cattle. On August 30, 1952, Vaughan was fishing in nearby Lost Lake, with his friend Bill Wimer. According to a witness, Wimer stood up in the boat, causing it to capsize, and both men drowned.

Oppenheimer

Posted: May 8, 2023 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing Leave a commentI watched the new trailer for Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer movie. Can it top Cormac McCarthy in three pages in The Passenger?

Good luck!

Scrapbasket

Posted: March 5, 2023 Filed under: Hollywood, writing Leave a comment

I’ve been reading.

and:

Did some deep reading about the history of Hollywood actually. Louis B. Mayer used to don diving equipment and salvage scrap metal in Boston Harbor:

That from:

Then he got the rights to show Birth of a Nation, and saw a magical new business. (He 4xed on the BoaN deal).

Keeping studios and theaters separate has been an ongoing war in the history of Hollywood. With streaming we are in a situation where they are once again the same.

Mayer:

In one of my Hollywood histories I found it documented that (iirc) a studio writer was expected to produce eleven pages a week, which seems like a reasonable number. However on re-searching I couldn’t find what book this was from. Maybe Genius of the System?

The exports of Saint Helena form a pleasing chart. The geography of Saint Helena is wild.

Would love to visit. Remembering Saturdays in my early mid teens when I would go to Globe Traveler Bookstore and read Lonely Planet books about practical travel to exotic places. Greenland, etc. How could a business that gave shelf space in downtown Boston to a travel book to Greenland stay? It couldn’t I guess, but the world might be poorer for it, Boston anyway, more sanded down.

I like the look of the mayor of East Palestine, Ohio. Following the train derailment with great interest. Recalling Sturgill Simpson, appearing on Trillbillies podcast, talking about how he used to work at a UNP yard. This is from memory but I believe it’s an accurate quote:

a train derailment is big boy pants

This one, a rec from Prof James, is a mind-expander:

The extent to which the demand for sugar drove slavery is troubling to consider.

Book of poems, or stories, or both. They’re really good! The cover:

Surah 109, Al-Kafirun, The Unbelievers, is one of the shortest in the Quran, you can read or listen to it here. Thomas Cleary renders it thus:

Worth listening to it recited. The tales of crowded buses in the Muslim world that calm when someone puts on a tape of Quran recitation interest me.

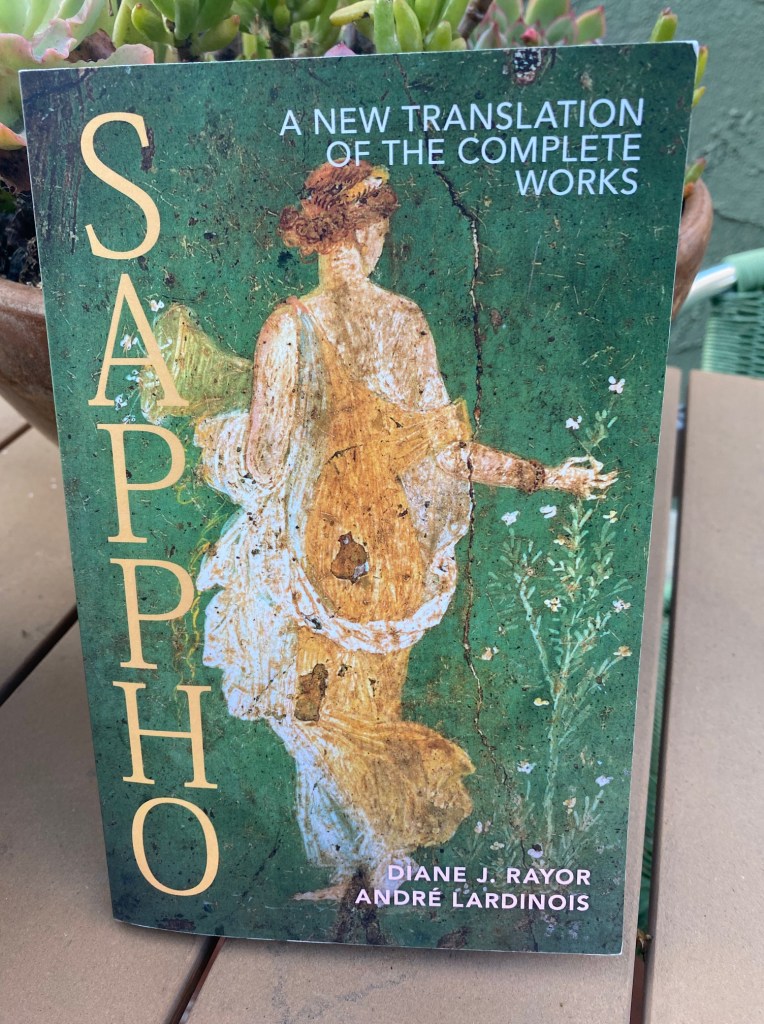

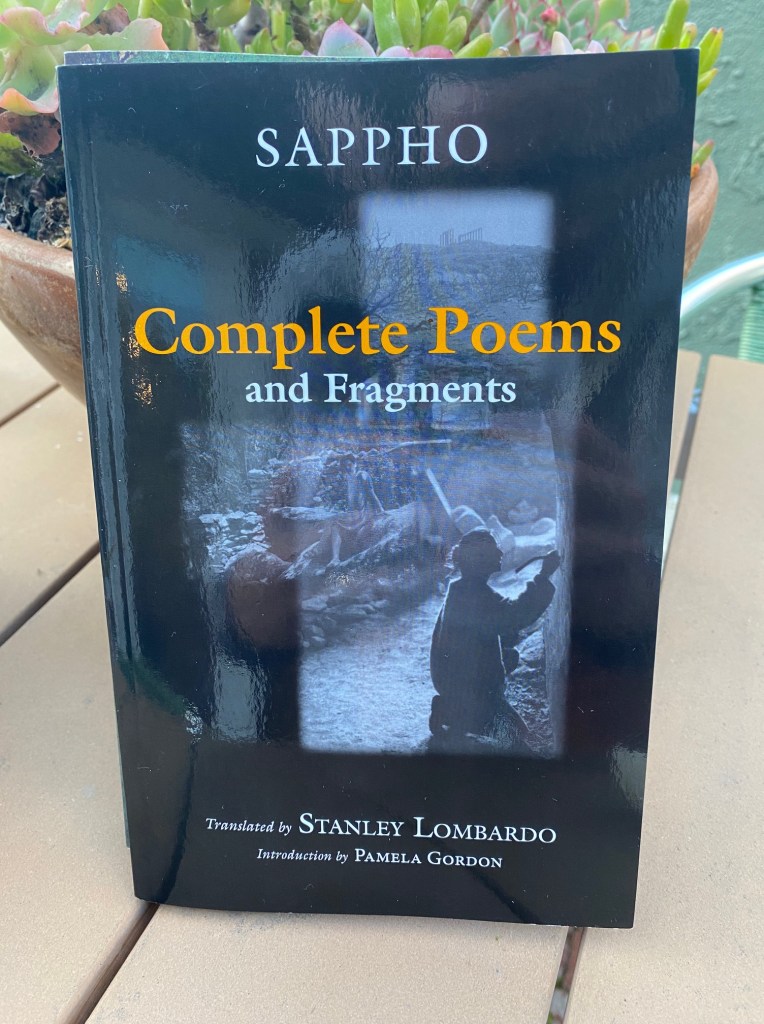

More Sappho fragments

Posted: February 12, 2023 Filed under: writing 2 Comments

Fragment 91

[I] never met anyone more irritating, Eirana,

than you.

Stanley Lombardo of University of Kansas has that one as

having never found her more annoying

than you, Irana

Fragment 39

sandals

of fine Lydian make, straps rainbow-dyed

covered her feet

says the footnote:

A scholiast (an ancient commentator who wrote notes in and around the main text) preserved this fragment in the margins of a manuscript of Aristophanes’ play Peace.

My favorite of all might be fragment 57

What farm girl has seduced you?

Draped in burlap,

she doesn’t even know to pull her rags

down over her ankles.

That line quotes by Antheneus, a second- to third-century BCE writer in his The Learned Banquet.

Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois set that one as:

What countrywoman bewitches your mind…

wrapped in country dress…

too ignorant to cover her ankles with her rags?

The way the less complete bits lay out on the page:

That from an Oxyrhynchus papyrus.

Spooky! A call from the distant past. In their introduction Rayor and Landinois paint a picture of Sappho as something like a 600 BCE Lana Del Rey, gathering a circle around her on Lesbos (closer to Turkey than to Greece).

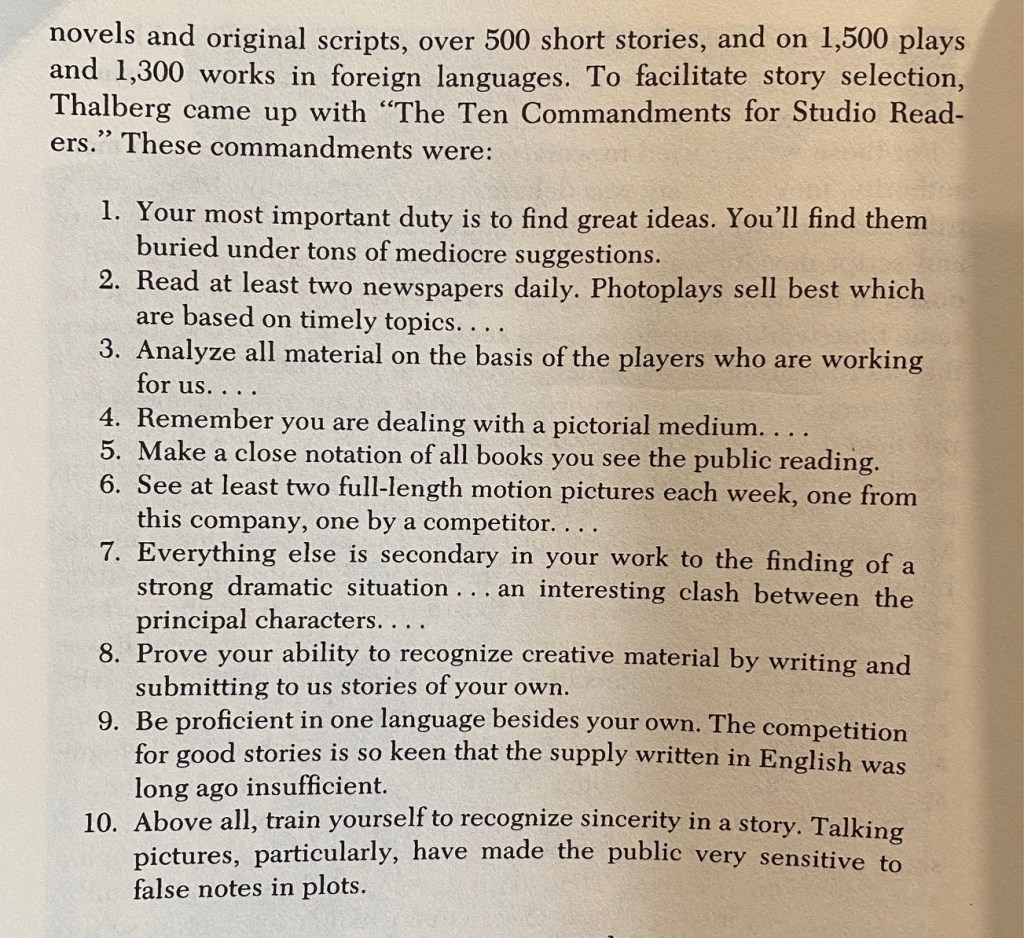

Ten Commandments for Studio Readers, from Thalberg

Posted: September 6, 2022 Filed under: Hollywood, writing Leave a comment

from The Genius of the System, Thomas Schatz.

John Steinbeck on San Francisco

Posted: August 23, 2022 Filed under: San Francisco, Steinbeck, Steinbeck, the California Condition Leave a commentThomas Wolf took that one for Wikipedia.

Can you remember anywhere in John Steinbeck’s fiction where he discusses San Francisco? Whole books about Monterey, but does he even mention the place? I couldn’t remember. A friend’s been working on Steinbeck’s letters, he couldn’t think of any mention either.

Turns out Steinbeck does talk about San Francisco in Travels with Charley in Search of America. The chapter begins:

I find it difficult to write about my native place, northern California. It should be easiest, because I knew that strip angled against the Pacific better than any place in the world. But I find it not one thing but many – one printed over another until the whole thing blurs.

He mentions growth:

I remember Salinas, the town of my birth, when it proudly announced four thousand citizens. Now it is eighty thousand and leaping pell mell on in mathematical progression – a hundred thousand in three years and perhaps two hundred thousand in ten, with no end in sight.

(The population of Salinas is, in 2022, 156,77.)

Then he writes some about mobile home parks, and property taxes, concluding:

We have in the past been forced into reluctant change by weather, calamity, and plague. Now the pressure comes from our biologic success as a species.

Then he gets going on San Francisco:

Once I knew the City very well, spent my attic days there, while others were being a lost generation in Paris. I fledged in San Francisco, climbed its hills, splet in its parks, worked on its docks, marched and shouted in its revolts. In a way I felt I owned the City as much as it owned me.

…

A city on hills has it over flat-land places. New York makes its own hills with craning buildings, but this gold and white acropolis rising wave on wave against the blue of the Pacific sky was a stunning thing, a painted thing like a picture of a medieval Italian city which can never have existed.

Steinbeck can’t stay though. He has to hurry on to Monterey to cast his absentee ballot (it’s 1960; he’s voting for John F. Kennedy).

The Golden West: Hollywood Stories, by Daniel Fuchs

Posted: August 14, 2022 Filed under: Hollywood, the California Condition, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a commentCritics and bystanders who concern themselves with the plight of the Hollywood screenwriter don’t know the real grief that goes with the job. The worst is the dreariness in the dead sunny afternoons when you consider the misses, the scripts you’ve labored on and had high hopes for and that wind up on the shelf, when you think of the mountains of failed screenplays on the shelf at the different movie companies…

brother, I hear you, but also c’mon, it beats working for a living.

An old-timer in the business, a sweet soul of other days, drops into my room. “Don’t be upset,” he says, seeing my face. “They’re not shooting the picture tomorrow. Something will turn up. You’ll revise.” I ask him what in his opinion there is to write, what does he think will make a good picture. He casts back in his mind to ancient successes, on Broadway and on film, and tries to help me out. “Well, to me, for an example – now this might sometimes come in handy – it’s when a person is trying to do something to another person, and the second fellow all the time is trying to do it to him, and they both of them don’t know.” Another man has once told me the secret of motion picture construction: “A good story, for the houses, it’s when the ticket buyer, if he should walk into the theater in the middle of the picture – he shouldn’t get confused but know pretty soon what’s going on.” “The highest form of art is a man and a woman dancing together,” still a third man has told me.

Beach cottage books

Posted: August 1, 2022 Filed under: writing Leave a commentDuring a stay at a beach cottage recently I picked some books off the shelf.

Paperback version of a beloved classic. But is this even readable?

Yeah I dunno…

Recalling that I read a section of All The King’s Men at a high school speech and debate contest. “Interpretive Reading” was not my strongest event.

Does this lady ever miss? Check out this plot:

Quinn Blackwood, Sugar Devil Swamp, Goblin. YES! How about:

This sounds like a bodice ripper but for men:

I put these books back and didn’t read any of them. If I had to pick I’d read about Goblin!

Kate Corbaley, Storyteller

Posted: July 29, 2022 Filed under: actors, Hollywood, screenwriting, the California Condition, writing Leave a commentAnother staff writer with a rather unconventional but valued talent was Kate Corbaley. At $150 a week, Corbaley was one of the few staffers whose salary was in the same range as Selznick’s…

Her specialty was not in editorial but rather as Louis Mayer’s preferred “storyteller.” Mayer was not a learned or highly literate man, and he rarely read story properties, scripts, or even synopses. He preferred to have someone simply tell him the story and he found Mrs. Corbaley’s narrational skills suited him. She never received a writing credit on an MGM picture, but many in the company considered her crucial to Mayer’s interest in stories being considered for purchase or production at any given time.

That’s from Thomas Schatz, The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era.

Corbaley’s brother was Admiral S. C. Hooper, “the father of naval radio,” if The New York Times is to be believed. What a family of communicators!

Storytelling is a current obsession in business. A few days ago I searched “storyteller” under Jobs on LinkedIn and found 35,831 results. Amazon, Microsoft, and Pinterest are all hiring some version of “storyteller,” as are Under Armor, Eataly and “X, the Moonshot Factory.” The accounting firm Deloitte is hiring Financial and Strategic Storytellers (multiple listings, financial and strategic storytellers are sought in San Diego, Miami, Chicago, Charlotte, Tampa, Las Vegas, and Phoenix).

Cool job.

It’s reported in City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s that one afternoon in May, 1936, Kate Corbaley summarized a novel that was already perceived as hot property. She told Louis B. Mayer

a new story about a tempestuous southern girl named Scarlett O’Hara.

Mayer wasn’t sure what to think, so he sent for Irving Thalberg, who declared:

Forget it, Louis. No Civil War picture ever made a nickel.

(This seems improbable: in 1936 Birth of A Nation would’ve held the record as one of if not the biggest movie of all time? Must track this tale to its source, will report.)