Carter’s, congealed electricity, AI and Needham

Posted: January 30, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, children, New England, Uncategorized Leave a comment

If you have a little kid in the US you will have some clothes from Carter’s. They sell them at Target and Wal-Mart as well as 1,000 or so Carter’s stores, and they cost $8.

Before I had a kid it didn’t occur to me that kids outgrow their clothes so fast they can’t cost too much.

When I see the Carter’s label, I think of my home town.

William Carter founded Carter’s in Needham, Massachusetts in 1865. Textiles were a big business in New England. Two inputs, labor and electricity, were cheap. Labor from excess farm children, and electricity from running streams? That would’ve been the earliest mode, what were they using by 1865? Coal?

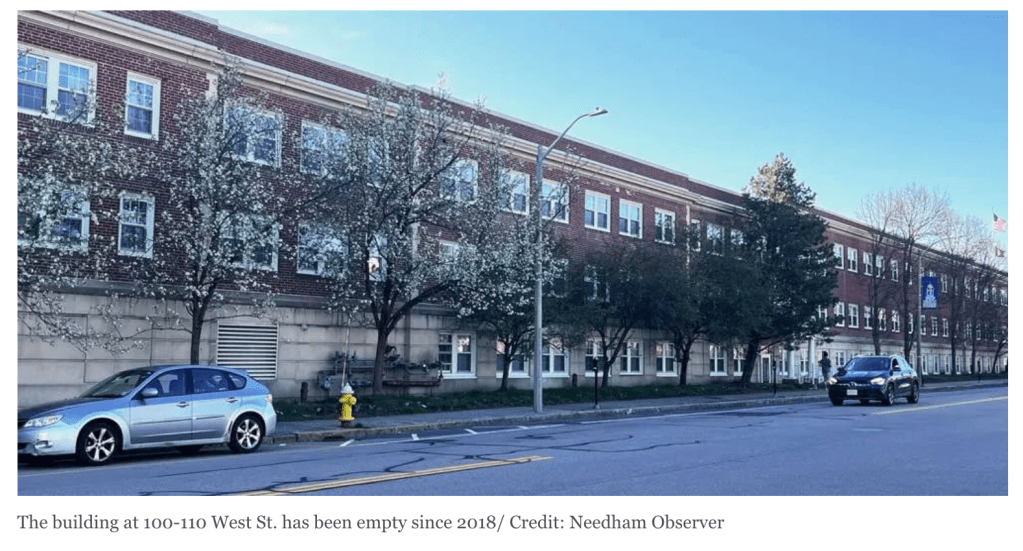

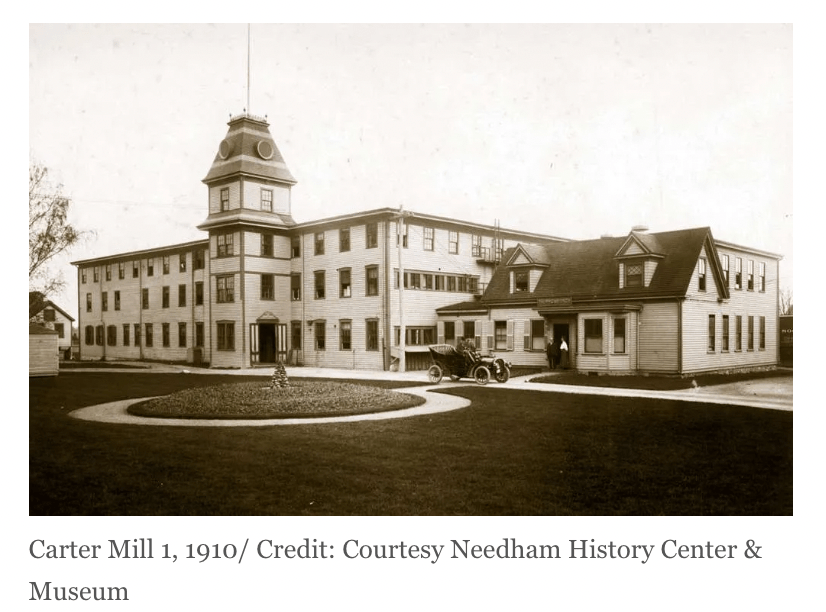

One of the biggest buildings in Needham, certainly the longest, is the former Carter’s headquarters, which stretches itself along Highland Avenue. A prominent landmark, it took a long time to walk past.

The story of Carter’s is a global economic story in miniature.

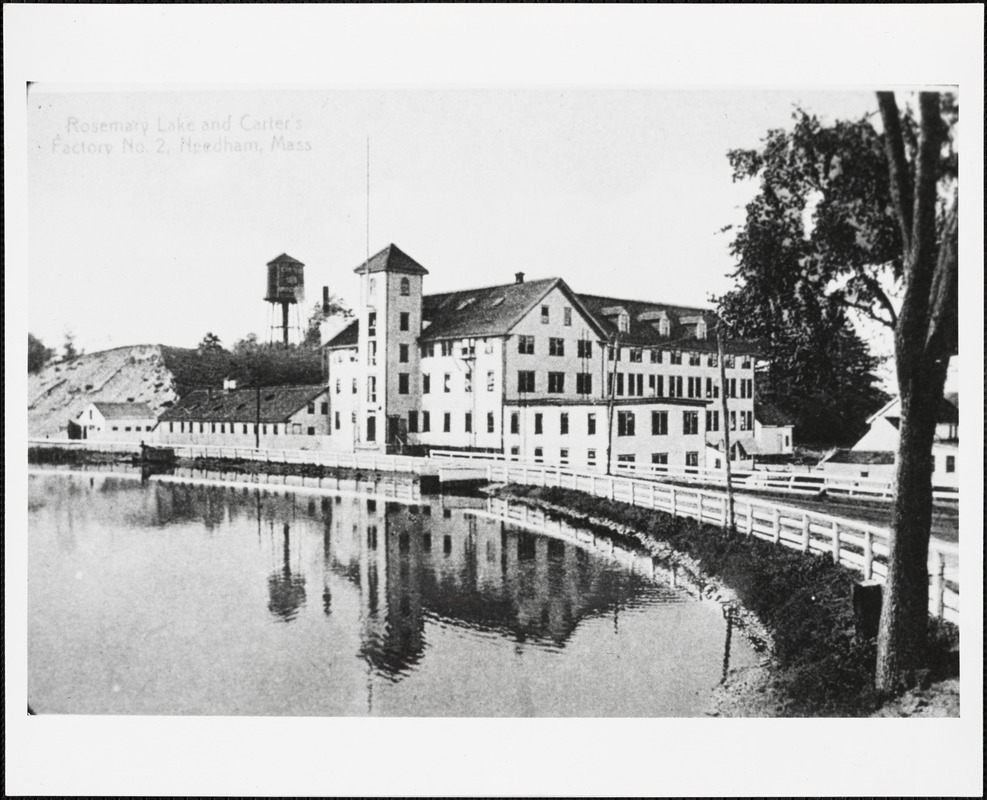

Old Carter mill #2, found here.

The Carter family sold the company in the 1990s. It went public in 2003. In 2005, Carter’s acquired OshKosh B’gosh, a company famous for making children’s overalls. This company started in 1895 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin (the name comes from an Ojibwe word, “The Claw,” that was the name of a local chief).

The term “B’gosh” began being used in 1911, after general manager William Pollock heard the tagline “Oshkosh B’Gosh” in a vaudeville routine in New York.[4] The company formally adopted the name OshKosh B’gosh in 1937.

OshKosh B’Gosh’s Wisconsin plant was closed in 1997. Downsizing of domestic operations and massive outsourcing and manufacturing at Mexican and Honduran subsidiaries saw the domestic manufacturing share drop below 10 percent by the year 2000.

OshKosh B’Gosh was sold to Carter’s, another clothing manufacturer for $312 million

The headquarters of Carter’s moved to Atlanta. Labor and electricity were cheaper in Georgia, Carter’s had been opening mills in the South for awhile. Now the clothes are made overseas. I look at the labels on Carter’s clothes: Bangladesh, India, Cambodia, Vietnam. If you factor in the shipping and the markup how much of that $8 is going to your garment maker in Bangladesh? Then again maybe it’s the best job around, raising Bangladeshis out of poverty, and soon Chittagong will look like Needham.

The former Carter’s headquarters, now vacant, became a facility for elder living. My mom worked there, briefly. Carter’s today is headquarted in the Phipps Tower in Buckhead, Atlanta, which I happened to pass by the other day.

The loss of the mill and the company headquarters was not a crisis for Needham. Needham is very close to Boston, an easy train ride away, and along of the 128 Corridor. There are growth businesses in the area, hospitals, biotech companies, universities. TripAdvisor is based in Needham. Needham is a pleasant town, there are ongoing talks to turn the former Carter’s building into housing. It would be close to public transport and walkable to the library and the Trader Joe’s. That seems to be stalled.

Needham has brain jobs, attached to a dense brain network, while brawn jobs are being shipped overseas. There are many other towns in Massachusetts where the old run down mill is a sad derelict as production moved first south and then overseas. These towns are bleak. Oshkosh, Wisconsin seems ok, but the shipping of steady jobs overseas is of course a major factor in our politics, Ross Perot was talking about it in 1992 and no one did anything about it and now Trump is the president.

A similar story lies in the history of Berkshire Hathaway – the original New Bedford textile mill, not the conglomerate Warren Buffett built on top of it using the same name. Buffett talks about this, I believe this is from the 2022 annual meeting:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I remember when you had a textile mill —

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, god.

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and it couldn’t —

WARREN BUFFETT: I try to forget it. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and the textiles are really just congealed electricity, the way modern technology works.

And the TVA rates were 60% lower than the rates in New England. It was an absolutely hopeless hand, and you had the sense to fold it.

WARREN BUFFETT: Twenty-five years later, yeah. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, you didn’t pour more money into it.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, that’s right.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And, no — recognizing reality, when it’s really awful, and taking appropriate action, just involves, often, just the most elementary good sense.

How in the hell can you run a textile mill in New England when your competitors are paying way lower power rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: And I’ll tell you another problem with it, too. I mean, the fellow that I put in to run it was a really good guy. I mean, he was 100% honest with me in every way. And he was a decent human being, and he knew textiles.

And if he’d been a jerk, it would have been a lot easier. I would have probably thought differently about it.

But we just stumbled along for a while. And then, you know, we got lucky that Jack Ringwalt decided to sell his insurance company [National Indemnity] and we did this and that.

But I even bought a second textile company in New Hampshire, I mean, I don’t know how many — seven or eight years later.

I’m going to talk some about dumb decisions, maybe after lunch we’ll do it a little.

Congealed electricity, what a phrase. In the 1985 annual letter, Buffett discusses the other input, labor, which was cheaper in the South, and why he kept Berkshire Hathaway running in Massachusetts anyway:

At the time we made our purchase, southern textile plants – largely non-union – were believed to have an important competitive advantage. Most northern textile operations had closed and many people thought we would liquidate our business as well.

We felt, however, that the business would be run much betterby a long-time employee whom. we immediately selected to be president, Ken Chace. In this respect we were 100% correct: Ken

and his recent successor, Garry Morrison, have been excellent managers, every bit the equal of managers at our more profitable businesses.… the domestic textile industry operates in a commodity business, competing in a world market in which substantial excess capacity exists. Much of the trouble we experienced was attributable, both directly and indirectly, to competition from foreign countries whose workers are paid a small fraction of the U.S. minimum wage. But that in no way means that our labor force deserves any blame for our closing. In fact, in comparison with employees of American industry generally, our workers were poorly paid, as has been the case throughout the textile business. In contract negotiations, union leaders and members were sensitive to our disadvantageous cost position and did not push for unrealistic wage increases or unproductive work practices. To the contrary, they tried just as hard as we did to keep us competitive. Even during our liquidation period they performed superbly. (Ironically, we would have been better off financially if our union had behaved unreasonably some years ago; we then would have recognized the impossible future that we faced, promptly closed down, and avoided significant future losses.)

Buffett goes on, if you care to read it, to discuss the dismal spiral faced by another New England textile company, Burlington.

Charlie Munger, in his 1994 USC talk, spoke on the paradoxes here:

For example, when we were in the textile business, which is a terrible commodity business, we were making low-end textiles—which are a real commodity product. And one day, the people came to Warren and said, ‘They’ve invented a new loom that we think will do twice as much work as our old ones.’

And Warren said, ‘Gee, I hope this doesn’t work because if it does, I’m going to close the mill.’ And he meant it.

What was he thinking? He was thinking, ‘It’s a lousy business. We’re earning substandard returns and keeping it open just to be nice to the elderly workers. But we’re not going to put huge amounts of new capital into a lousy business.’

And he knew that the huge productivity increases that would come from a better machine introduced into the production of a commodity product would all go to the benefit of the buyers of the textiles. Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.

That’s such an obvious concept—that there are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Is something similar happening with AI? Who will it make rich, and at what cost? To whose ribs will the profits stick?

I’m not sure we could call AI congealed but it is more or less just more and more electricity run through expensive processors. Who will win from that? So far it’s been the makers of the processors, but if DeepSeek shows you don’t need as many of those the game is changed. Personally I’m unimpressed with DeepSeek – try asking it what happened in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

How does Carter’s itself continue to survive? Target’s own brand, Cat & Jack, is right next door on the shelves. Could another company shove Carter’s aside if they can cut the margins even thinner, get the price down to $7? Here’s what Carter’s CEO Michael Casey has to say in their most recent annual letter:

Hard to build the operational network Carter’s has over 150+ years. There will be a challenge awaiting the next CEO of Carter’s as Michael Casey is retiring. Carter’s stock ($CRI) is pretty beaten up over the past year, down 30%. A possible macro problem for Carter’s is that the number of births in the United States appears to be declining.

It is powerful, when I’m changing my daughter, to contemplate my home town, and global commerce, and the people in Cambodia who made these clothes, and the ways of the world.

Gizmodo interview

Posted: January 25, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, the California Condition Leave a comment

As Matt at the office put it, they came out SWINGING with Luigi as the first question:

I declare the event both “upsetting” but also “cool”? Maybe I do need media training. Here’s a link.

Here’s what matters:

Streaming next day on MAX. Is it still called HBO Max in Australia? I know they’ve got Max in Europe and LatAm.

Occurs to me this site has been lax on one of our missions, reporting news from Helys around the world. There’s just too much!

Texas Wines

Posted: January 25, 2025 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

(source. post title can be sung to the tune of Khuangbin and Leon Bridges, “Texas Sun”)

From my father in law I came into possession of several bottles of Texas wine.

Texas has the most native grapes of any state, we are told by Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson in their World Atlas of Wine (8th Edition), but these are not vinifera, the species of grape we’re usually talking about to make wines. You can make wines out of other grapes, but they tend to have a quality described as “foxy,” which seems to be like musty. The Concord grape’s taste is sometimes suggested as a referent.

Johnson and Robinson:

Of the 65-70 species of the genus Vitis scattered around the world, no fewer than 15 are Texas natives – a fact that was turned to important use during the phylloxera epidemic. Thomas V Munson of Denison, Texas, made hundreds of hybrids between Vitis vinifera and indigenous vines in his eventually successful search for immune rootstock. It was a Texan who saved not only France’s but the whole world’s wine industry.

they continue:

As much as 80% of all Texas wine grapes are grown in the High Plains, but about three-quarters of them are shipped to one of the 50 or so wineries in the Hill Country of Central Texas, west of Austin. The vast Texas Hill Country AVA is the second most extensive in the US, and includes both the Fredericksburg and Bell Mountain AVAs within it. The total area of these three AVAs is 9 million acres (3.6 million ha), but a mere 800 acres (324ha) are planted with vines.

Their map:

Of these wines, Pedernales Block 2 was most impressive to me. This could be a competition wine. Set it against your French and Spanish and Italian and California wines and see if it can’t hold up.

It looks like Kuhlken Vineyards is right across the river from Lyndon Johnson’s ranch. He used to drive his amphibious car in the Pedernales.

(source)

Now, if you’re looking for structure in your wines, Texas ain’t the place.

This one initially smelled of sweet barbecue sauce. Not saying that’s a bad thing, just something you should know. I would say it “opened up” most generously and I respected this wine, I felt like by the time I’d finished a glass this wine and I were pals.

The Davis Mountains AVA seems like more a hope than a real center of production for now, but someday it could be really special. Next time I’m in Marfa I will try Alta Marfa wines.

How much wine do you think you need to drink to become a professional wine critic?

Lettie Teague of the WSJ my model here. I think I drink a reasonable amount of wine, but probably not even close to the professional level.

The way in to wine for me is geography. Tastes and notes are fine to discuss at the tasting room but I want to go to the Margaret River and the base of Etna and Yountville and St. Emilion and yes, even Lubbock. The Hill Country for sure.

My mother in law was a pioneer of Texas wine writing, I wish I could discuss these wines with her. She has gone to the great AVA in the sky.

Lincoln in New Orleans (featuring final answer on was Abraham Lincoln gay?)

Posted: January 18, 2025 Filed under: Mississippi, New Orleans, presidents Leave a comment

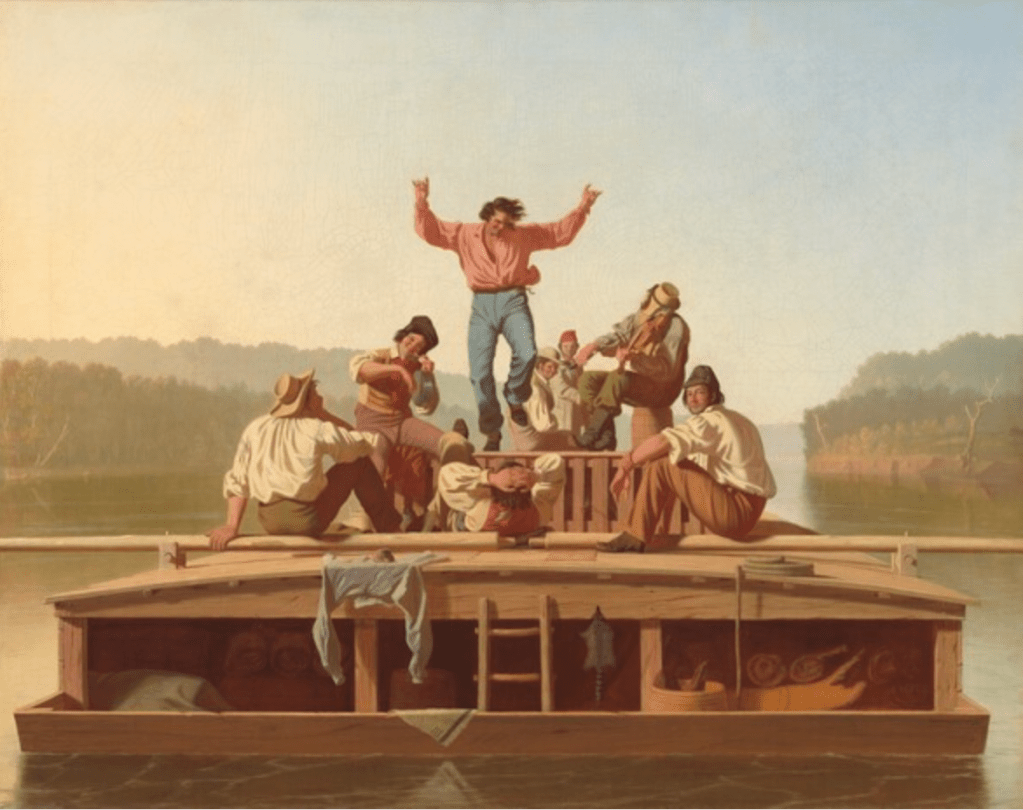

In the year 1828 nineteen year old Abraham Lincoln went on a flatboat trip with a local twenty one year old named Allen Gentry. He would be paid eight dollars a month plus steamboat fare home. They left from Spencer County, Indiana, down the Ohio to the Mississippi.

The great New Orleans geographer and historian Richard Campanella wrote a whole book, Lincoln In New Orleans, about Lincoln’s experience on this trip and another down in New Orleans. It’s a really illuminating work on Lincoln, the Mississippi River at that time, the floatboatman life, early New Orleans.

If you need step by step instructions on building a flatboat, they’re in Campanella’s book. (People back then worked so hard!)

Campanella tells us in vivid reconstruction from various sources what this trip must’ve been like:

the Mississippi River in its deltaic plain no longer collected water through tributaries but shed it, through distributaries such as bayous Manchac, Plaquemine, and Lafourche (“the fork”). This was Louisiana’s legendary

“sugar coast,” home to plantation after plantation after plantation, with their manor houses fronting the river and dependencies, slave cabins, and

“long lots” of sugar cane stretching toward the backswamp. The sugar coast claimed many of the nation’s wealthiest planters, and the region had one of the highest concentrations of slaves (if not the highest) in North America. To visitors arriving from upriver, Louisiana seemed more Afro-Caribbean than American, more French than English, more Catholic than Protestant, more tropical than temperate. It certainly grew more sugar cane than cotton (or corn or tobacco or anything else, probably combined).

To an upcountry newcomer, the region felt exotic; its society came across as foreign and unknowable. The sense of mystery bred anticipation for the urban culmination that lay ahead.

What Lincoln did in New Orleans is recorded only in a few stray remarks from the man himself and secondhand stories remembered afterwards by those he told them to, who then told them to William Herndon, biographer and law partner of Lincoln. (now they can be found in a volume called Herndon’s Informants). What was Lincoln like in New Orleans?

Observing the behavior of young men today, sauntering in the French Quarter while on leave from service, ship, school, or business, offers an idea of how flatboatmen acted upon the stage of street life in the circa-1828 city. We can imagine Gentry and Lincoln, twenty and nineteen years old respectively, donning new clothes and a shoulder bag, looking about, inquiring what the other wanted to do and secretly hoping it would align with his own wishes, then shrugging and ambling on in a mutually consensual direction. Lincoln would have attracted extra attention for his striking physiognomy, his bandaged head wound from the attack on the sugar coast, and his six-foot-four height, which towered ten inches over the typical American male of that era and even higher above the many New Orleanians of Mediterranean or Latin descent.

Quite the conspicuous bumpkins were they.

One cannot help pondering how teen-aged Lincoln might have behaved in New Orleans. Young single men like him (not to mention older married men) had given this city a notorious reputation throughout the Western world; condemnations of the city’s wickedness abound in nineteenth-century literature. A visitor in 1823 wrote,

New Orleans is of course exposed to greater varieties of human misery, vice, disease, and want, than any other American town. … Much has been said about [its] profligacy of manners, morals… debauchery, and low vice … [T]his place has more than once been called the modern Sodom.

Campanella considers what we know about Lincoln and women:

I consider the matter concluded that Abe was a gentle shyguy ladykiller.

I found this passage very real:

Campanella gives us the political context of the time:

There was much to editorialize about in the spring of 1828. A concurrence of events made politics particularly polemical that season. Just weeks earlier, Denis Prieur defeated Anathole Peychaud in the New Or-leans mayoral race, while ten council seats went before voters. They competed for attention with the U.S. presidential campaign— a mudslinging rematch of the bitterly controversial 1824 election, in which Westerner Andrew Jackson won a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote in a four-candidate, one-party field, but John Quincy Adams attained the presidency after Congress handed down the final selection. Subsequent years saw the emergence of a more manageable two-party system. In 1828, Jackson headed the Democratic Party ticket while Adams represented the National Republican Party (forerunner of the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party). Jackson’s heroic defeat of the British at New Orleans in 1815 had made him a national hero with much local support, but did not spare him vociferous enemies. The year 1828 also saw the state’s first election in which presidential electors were selected by voters-white males, that is—rather than by the legislature, thus ratcheting up public interest in the contest. 238 Every day in the spring of 1828 the local press featured obsequious encomiums, sarcastic diatribes, vicious rumors, or scandalous allegations spanning multiple columns. The most infamous-the “coffin hand bills,” which accused Andrew Jackson of murdering several militiamen executed under his command during the war—-circulated throughout the city within days of Lincoln’s visit. 23% New Orleans in the red-hot political year of 1828 might well have given Abraham Lincoln his first massive daily dosage of passionate political opinion, via newspapers, broadsides, bills, orations, and overheard conversations.

Before they got to New Orleans, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked by a group of seven Negroes, possibly runaway slaves? Little is known for sure about the incident, except that they messed with the wrong railsplitter. Lincoln was famously strong and a good fighter:

In a remarkable bit of historical detective work, Campanella concludes that a woman sometimes called “Bushan” may have been Dufresne, and puts together this incredible map:

Really impressed with Campanella’s work, I also have his book Bienville’s Dilemma, and add him to my esteemed Guides to New Orleans. Campanella goes into some detail about how and in what forms Lincoln would’ve encountered slavery on this trip. Any dramatic statement about it he made during the trip though seems historically questionable. When Lincoln talked about this trip in political speeches, he used it as an example of how he’d once been a working man. For example, 1860 in New Haven:

Free society is such that a poor man knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition-when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him!’

Campanella does cite a letter Lincoln wrote in 1860 where he did speak on what he saw of slavery:

Making a flatboat trip was a rite of passage for a young buck of the Midwest at that time. Whether it brought Lincoln to full maturity is discussed in a poignant and comic anecdote:

An awkward incident one year after the New Orleans trip yanked the maturing but not yet fully mature Abraham back into the petty world of past grievances. How he dealt with it reflected his growing sophistication as well as his lingering adolescence. Two Grigsby brothers— kin of Aaron, the former brother-in-law whom Abraham resented for not having done enough to aid his ailing sister Sarah Lincoln-married their fiancées on the same day and celebrated with a joint “infare.” The Grigsbys pointedly did not invite Lincoln. In a mischievous mood, Abraham exacted revenge by penning a ribald satire entitled “The Chronicles of Reuben,” in which the two grooms accidentally end up in bed together rather than with their respective brides. Other locals suffered their own indignities within the stinging verses of Abraham’s poem, nearly resulting in fisticuffs. The incident botses tected and exacerbated Lincoln’s growing rift with all things related to Spencer County.

An article version of Campanella’s book is available free.

That painting is of course Jolly Flatboatmen, which we discussed back in 2012.

Living Room on the tracks

Posted: January 16, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, railroads Leave a comment

A photo by O. Winston Link, at the Smithsonian. That is Lithia, Virginia.

Stuart Spencer (1927-2025)

Posted: January 14, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, presidents, the California Condition 2 Comments

I read in The LA Times that Stuart Spencer died. His Miller Center Oral History interview is one of the most vivid on the rise of Ronald Reagan, California, politics in general:

After many discussions with [Reagan], we realized this guy was a basic conservative. He was obsessed with one thing, the communist threat. He has conservative tendencies on other issues, but he can be practical.

When you look at the 1960s, that’s a pretty good position to be in, philosophically and ideologically. Plus, we realized pretty early on that the guy had a real core value system. Most people in my business don’t like to talk about that, but you know something? The best candidates have a core value system. Either party, win or lose, those are still the best candidates. They don’t lose because of their core value system. They lose because of some other activity that happens out there. But the best candidates to deal with, and to work with, are those who have that. A lot of them have it and a lot of them don’t, but Reagan had it.

The power players of Southern California:

Holmes Tuttle was a man of great . . . He was a car dealer, a Ford dealer in southern California and he also had some agencies in Tucson, I think. Holmes was a guy that came from Oklahoma on a freight car. He had no money and he started working—I don’t think he finished high school—for a car dealership, washing cars, cleaning cars. He’s a man of tremendous energy, tremendous drive and strong feelings—which most successful businessmen have—about how the world should be run, how the country should be run as well as how their business should be run and how your business should be run. They’re always tough and strong that way. That was Holmes’ background.

In the southern California—I won’t say California because we have two segments, north and south—framework of the late ’30s and the ’40s, there were movies made about a group. I can’t remember what they were called, but there were 30 of them. In this group were the owner and publisher of the L.A. Times, the [Harry] Chandler family top business guys, Asa Call of what is now known as Pacific Insurance. It was Pacific Mutual Insurance then, a local company. Now it’s a national company. Henry Salvatori, the big oil guy; Holmes; Herbert Hoover, Jr.; the Automotive Club of Southern California; that type of people, they ran southern California. They had the money. They had the mouth, the paper. They ran it. [William Randolph] Hearst was a secondary player. He had a paper, but he was secondary player. He wasn’t in the group. Hearst was more global.

These guys worried about everything south of the Tehachapi Mountains. That’s all they worried about. They worried about water. They worried about developments. They’ve made movies about that. Most of it’s true. The Southern Pacific was the big power player, but these guys were trying to upset the powers of the Southern Pacific to a degree. Holmes Tuttle came out of that power struggle, that power group.

He was a guy who would work hard. Asa Call was the brains. Holmes was the Stu Spencer, the guy that went out and made it happen. He was aggressive and he played a role. He started playing a role in the political process in the ’50s, post Earl Warren. None of these guys were involved with Earl Warren to any degree. But after Earl Warren and Nixon, they were players there. They never were in love with Nixon, but they were pragmatic. The Chandlers were in love with Nixon, and a few others, but with these bunch of guys, Ace would like Nixon. Holmes was the new conservative and Nixon was a different old conservative.

There were little differences there. Holmes emerged in the new conservative element and was heavily involved in the Goldwater campaign of ’64. Of course that’s a whole ’nother story. When Nixon went down the tube all of a sudden—it was lying there latent in the Goldwater movement and they were waiting for Nixon to get beat and when he did [sound effect]—here they were up in your face.

Reagan was the first legitimate person that Holmes was absolutely, totally, in synch with, and who he totally loved.

On Ron and Nancy:

Here’s an important point in my story. We met with the Reagans. The Reagans are a team politically. He would have never made the governorship without her. He would have never been victorious in the presidential race without her. They went into everything as a team.

It was a great love affair, is a great love affair. Early on I thought it was a lot of Hollywood stuff. I really did. I could give you anecdotes of her taking him to the train when he had to go to Phoenix because they didn’t fly in those days, or to Flagstaff to do the filming of the last segments of that western he was doing. We’d be in Union Station in L.A. at nine o’clock at night. They’re standing there kissing good-bye and it goes on and it goes on and it goes on. I’m embarrassed and I’m saying,

Wow.It was just like a scene out of Hollywood in the 1930s, late ’30s, ’40s. I tell you that, but then I tell you now twenty-five, thirty, forty years later, whatever it is, it was a love affair. It was not Hollywood.At that time I thought, oh, boy. It’s not only a partnership, it’s a great love affair. She was in every meeting that Bill and I were at with Reagan, discussing things, us asking questions, with him asking us questions. The curve of her involvement over the years was interesting because she was in her 40s then probably. She always lied about her age so I can’t tell you exactly, but she was somewhere around 45, I’d guess. She was quiet. With those big eyes of hers, she’d be watching you. Every now and then she’d ask a question, but not too often.

As time went on—I’m talking about years—she grew more and more vocal. But she was on a learning curve politically. She learned. She’s a very smart politician. She thinks very well politically. She thinks much more politically than he thinks. I think it’s important that Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan were the team that went to the Governor’s office and that went to the White House. They did it together. They always turned inward toward each other in times of crisis. She evolved a role out of it, her role. No one else will say this, but I say this: she was the personnel director.

She didn’t have anything to do with policy. She’d say something every now and then and he’d look at her and say,

Hey, Mommy, that’s my role.She’d shut up. But when it came to who is the Chief of Staff, who is the political director, who is the press secretary, she had input because he didn’t like personnel decisions. Take the best example, Taft Schreiber, who was his agent out at Universal for years, and Lew Wasserman. After we signed on, Taft was in this group of finance guys and he said to me,Kid, we’ve got to have lunch.I had lunch with Taft and he proceeded to tell me,

You’re going to have to fire a lot of people.I said,What do you mean?He said,Ron—meaning Reagan—has never fired anybody in his life.He said,I’ve fired hundreds of people. He’s never fired anybody.I laughed. I said to myself, Taft’s overstating the case. Taft was right. I fired a lot of people after that.Reagan hated personnel problems. He hated to see differences of opinion among his staff. His line was,

Come on, boys. Go out and settle this and then come back.You’re going to have a lot of that in politics. You’re going to have a lot of that in government. That’s what makes the wheels go round. It doesn’t mean that they’re not friends or anything. They have differences of opinion, but Reagan didn’t like that too much, especially over the minutia, and it usually happens over the minutia.

The sum total of Reagan:

The sum total of him is simply this: here’s a man who had a basic belief, who thought America was a wonderful, great country. I don’t think you can go back through 43 Presidents and find a President of the United States who came from as much poverty as Reagan came from; income-wise, dysfunctional families. I can’t quite remember where [Harry] Truman came from, but you’re not going to find one.

This guy came from an alcoholic family, no money, no nothing. He was a kid who was a dreamer. He dreamed dreams and dreamed big dreams and went out to fulfill those dreams with his life and he did it. As he moved down his career and got really involved in the ideological side of the political spectrum, which is where he started, he had real concerns about all this leaving us because of communism.

You look back—some of it sounds a little silly—but at the time there was perceived all kinds of threats, all over the world about communism moving into Asia, moving into Africa. That was the driving force behind his political participations. It was the only thing that he really thought about in depth, intellectualized, thought about what you can do, what you can’t do, how you can do it.

With everything else, from welfare to taxation, he went through the motions. Now, this is me talking, but every night when he went to bed, he was thinking of some way of getting [Leonid Ilyich] Brezhnev or somebody in the corner. He told me this prior to the beginning of the presidency. Because I asked questions like, What the hell do you want this job for?

I’d get the speech and the program on communism. He could quote me numbers, figures. He’d say, We’ve got to build our defenses until they’re scary. Their economy is going down and it’s going to get worse. I’m simplifying our discussion. He watched and he fought for defense. God, he fought for defense. He cut here, he cut there for more defense. He took a lot of heat for it. All the time he delivered, in his mind, the message to Russia, we’re not going to back off. We’ll out-bomb you. We’ll out-do everything to you.

His backside knew that we have the resources, this country has the resources and the Russians don’t. If they try to keep up with us defensively, they’re going to be in poverty. They’re going to be economically dead and an economically dead country can only do one of two things, either spring the bomb or come to the table. He was willing to roll those dice because he absolutely had an utter fear of the consequences of nuclear warfare.

Again he was lucky. He couldn’t deal with Brezhnev. He was over the hill and out of it. [Yuri Vladimirovich] Andropov was gone, dead. Reagan lucked out. In comes this guy [Mikhail] Gorbachev who was smart enough to see the trend in his own country. He started talking with Reagan about cutting a deal. That’s what it got down to. In that context Reagan was very benevolent. He was willing to give up a lot. If this guy was serious and willing to go down this road, he was willing to give up things to get the job done, which was to get rid of the cold war. To him the cold war was the threat of nuclear holocaust in this country and other countries.

That was a dream that he had before he was in the presidency. These words I’m giving you and interpreting for you were given to me prior to his election to the presidency. If you do a lot of research, you’ll see that he was always asking questions of the intelligence people, What’s the state of the economy in Russia? He must’ve had a Dow Jones bottom line in his mind—what he thought it was going to take to do it—because he always knew how many nukes we had and where they were. He was really into this.

Young

Does that mean that Reagan was a visionary?

Spencer

I don’t know. He was a dreamer. He was a dreamer. He dreamed that he was going to be the best sportscaster in America, that he was going to be one of the better actors in Hollywood. You know he got tired of playing the bad guy alongside Errol Flynn, who got the women all the time. But he still dreamed big dreams. That’s the way he was.

On Reagan’s interpersonal style:

Young

He was good at communications obviously. How was he at working the room with politicians?

Spencer

Terrible. Ronald Reagan is a shy person. People don’t understand this. He was not an introvert. Nixon was almost an introvert and paranoid. That’s a bad combination. Reagan was shy. People who I met through the years said to me,

I saw President Reagan at this,orI saw President Reagan one-on-one, two or three people in the Oval Office,or something. He never talked about anything substantive. He just told jokes.Ronald Reagan used his humor and his ability to break the ice. He wasn’t comfortable with you and you coming in the Oval Office with strangers and talking.

Number one, he’s not going to tell you about what he’s doing. He doesn’t think it’s any of your damn business. Secondly, he’s not comfortable and so he uses his humor. He can do dialects. I mean the Jewish dialect, a gay dialect. He can tell an Irish ethnic joke. The guy was just unbelievably good at it and he’d break the ice with it. You’d listen to him. But if you were that type of person, you’d walk out of there and you’d say,

What the hell were we talking about? He didn’t tell me anything.“

The Reagans had very few friends:

The Reagans never had a lot of friends. I cannot sit here today and tell you of a good, close, personal friend. They had each other and a lot of acquaintances. Maybe Robert Taylor was, maybe Jimmy Stewart was, some of those people. Maybe Charlie Wick and his wife, but other than that, I don’t know of any that they had. The Tuttles? They were not what you’d call close friends of theirs. They did things together but . . . it was he and Nancy.

An aside on Jimmy Carter:

The primary campaign for Jimmy Carter, 1976, was one of the best campaigns I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. They did an outstanding job. The guy in January was nine per cent in the polls in terms of his name ID. He ends up getting the nomination. Lots of things had to go right for them. Lots of breaks they had to get, breaks that they didn’t create, but they got them.

All that considered, the primary campaign was just an outstanding one. It was a lot of Jimmy Carter’s effort. He worked his tail off. Things kept setting up for him. The Kennedys kept vacillating and going this way and that. Everything kept setting up for him. They ran an outstanding campaign.

They had problems in ’80 because issues caught up with them. Their governance was not as good as their ability to run, which happens. I attribute most of it to his micromanagement. All of the Reagan people learned a lot from watching that because we had the opposite. [laughs]

The whole thing is great, on Bush, Dan Quayle, Clinton, Thatcher, it’s like 129 pages long.

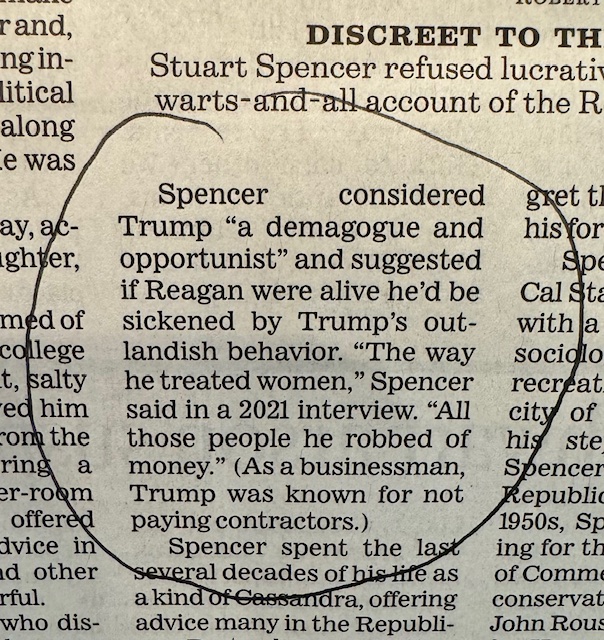

Two items to note from the obituary, by Mark A. Barabak:

and:

Spencer voted third party in 2016, for Joe Biden in 2020 and for Kamala Harris in 2024.

Some final advice from Spencer:

Finally I gave some major paper interview. It was on the plane. Marilyn [Quayle] was there and Dan Quayle was there. I was here and the press guy was here. The press guy starts out kind of warm and fuzzy and he says,

Who are your favorite authors?He looks at Marilyn, and he says,Who are my favorite authors?Oh, God.The second question is something about music. My position is, if you really haven’t thought about it in your own life, about who your favorite authors are, you can always say [Ernest] Hemingway. There are some names out there that you can use. If it’s music, you can say the Grateful Dead. Say anything you want to and think about it afterwards.

I was wrong, I like this guy better.

Did not love this vibe

Posted: January 13, 2025 Filed under: the California Condition Leave a comment

Nor

Today the air is perfect! There is the National Weather Service declaring the PDS however:

Edge case

Posted: January 11, 2025 Filed under: the California Condition Leave a commentJust after 5:30 pm Thursday, on a walk, with daughter strapped to me, relieved the worst is over. We round the corner to Fairfax and see Runyon Canyon on fire.

Like a volcano erupting. It looks like Vesuvius I thought, and then I realized I’d never seen Vesuvius except in illustrations. Maybe painted in the wall of an Italian restaurant? Or is that Mount Etna? Was I thinking of my dad describing Mount Etna?

I’d been on a smoking volcano in Guatemala (or was it Nicaragua? We roasted marshmallows) but had I ever seen one glowing?

The plaster casts of dead people in Pompeii, those I had seen, in National Geographic probably. I did not wish to become one. Time to pack.

The LA as I understood it as a youth in Massachusetts, the sense of LA, before I’d ever been there: convertibles palm trees swimming pools, soulless, “shallow.” Frequent natural disasters. The LA riots, the LA Lakers, both were viewed in Boston with fear, confusion, distress, upset, disquiet.

Imagine my surprise when I moved there for a job and loved it. It was like the famous story from Hockney:

The Los Angeles basin is so blessed, sunny almost every day, warm, rarely too hot. The beach, the mountains. When I arrived it was cheap, believe my rent was $900 for my own comfy place, walkable to LACMA and the tar pits and the movies, many bars and more restaurants and food stands than I could try. And the people! You could ask someone what they were up to and they’d say I’m developing.

California is on the edge, edge of the country, edge of the continent, edge of what’s acceptable, edge of politics, technology, edge of destruction. It’s all moving. You can’t expect it to stay.

The deadliest natural disasters in LA history are floods. The St Francis dam disaster, if you count that as “natural.” Six hundred some people washed to see. The 1938 flood. The river’s in that ugly concrete basin to keep floods contained. Last couple winters when the atmospheric rivers came there were many days when you could see why.

Back from my walk we watched the TV news. TV news: that’s a way to see LA and a way LA sees itself. The scale of LA first showed itself to me when I watched TV news and saw OJ’s Bronco.

Everybody’s been telling each other to stay safe. Stay safe! It’s like, ok! But what can you do? It’s like asking “how was your flight?”

Later that night I observed dense traffic on Fairfax as evacuees drove south. Though it was close to “bumper to bumper” there was no honking and it seemed like very little unpleasantness. Tension, sure, but people weren’t taking it out on each other. Reminded of Orwell’s quote: when it comes to the pinch, human beings are heroic. There are scattered tales of looters and opportunistic thieves on TV, but almost everyone is looking for ways to be helpful.

What’s the play? We must watch ourselves that capitalism doesn’t zombify our humanity like a cordyseps on an ant. (Also: “almost inevitable”? bad writing and thinking. Also inaccurate LA is HUGE it’s not gonna ALL burn down).

Nithya was ahead, warning about the wind event. See here for more on the local spooky winds. There’s a whole literature. It consists of a couple lines of Chandler reprinted by Didion (LA literary history in a nutshell).

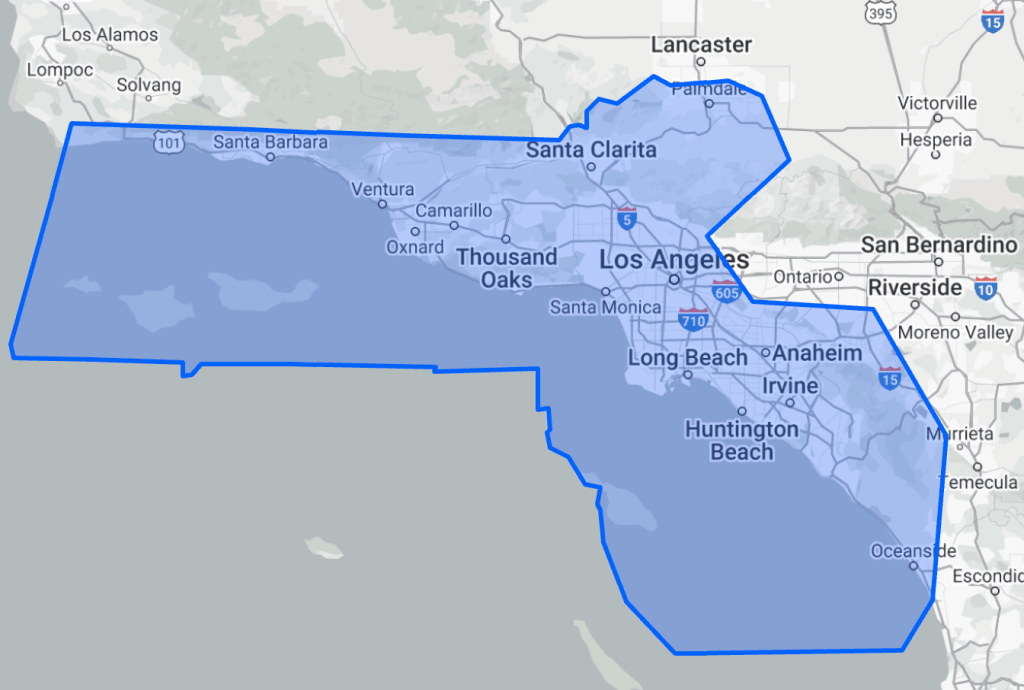

Some remarks in the news etc make me wonder if everyone comprehends the scale of Los Angeles. It’s quite vast. The Palisades Fire and the Altadena fire are about twenty five miles apart, on a straight line, for example. Here’s Massachusetts overlaid on Los Angeles:

(Is that helpful?) I guess my point is there’s like one fire that’s in like East Boston and one that’s in like Framingham. The Sunset fire, my Vesuvius, now out, would be in I dunno Newton? Very different experiences that in the news may be lumped together as “LA.” Reminded me of when Bronson of Scarsdale, NY was in Tennessee and people asked him if 9/11 affected him. Yes, but it’s not like next door.

This is a faulty comparison as almost all of both the Palisades and Eaton fires are happening in national forest/recreation area or other wildlands, not built up areas.

Three good friends have lost their homes in Palisades. I was impressed with their reactions. Stoic humor. Cool. Several friends and friendlies have lost homes in Altadena. Displacement high, anxiety high, lots of friends in hotels or friends’ houses or had to leave for a scary night and come back. Dogs in hotels, people evacuating horses. Overall disturbance and on-edge-itude are at high. On Monday the biggest problem in LA was housing. Now there are 10,000 fewer places to live and +10,000 (?) more homeless people.

Smoke east, smoke west. Inhaling smoke from wildfires is bad for you, I’ve seen the studies. Burnt houses and cars and asbestos and drywall, melted Emmys. Imagine the horrible particulates. Walking around was giving me a small headache. But what’s the point in reading scary articles, I gotta breathe something.

You know when you light a candle? Most of the smoke and scent comes when you blow it out.

West down Melrose, towards Palisades fire.

Friends dear and distant have reached out, from Australia and Sweden and Japan and Texas, New York, Massachusetts. We’re fine for now. Resisting leaving town. That feels like abandoning ship. If we were gonna leave we would take a treasured painting of a dog, Johnathan. Taking Johnathan off the wall felt like taking down the American flag.

It keeps seeming over and people have written their eulogies, but we consider this an update from the ongoing catastrophe/circus/intermittent paradise that is LA!

Here’s one by Piranesi, from the Fantastic Ruins show :

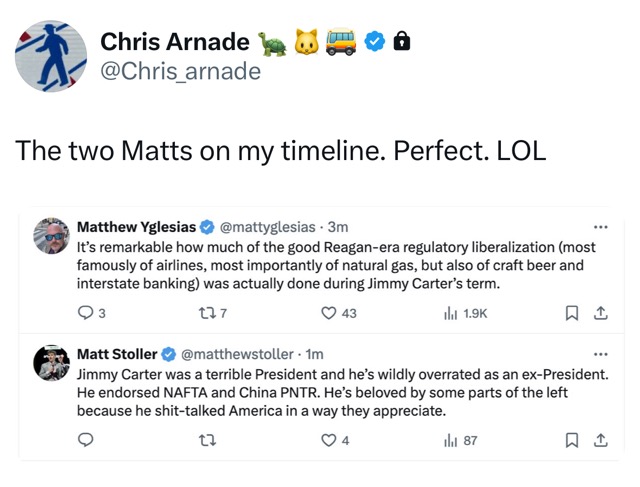

Jimmy Carter reconsidered

Posted: January 6, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, presidents 1 Comment

Tyler Cowen didn’t like him. George Will didn’t like him. Ken Layne made me laugh:

Aren’t we always interested in the history that came right before we appear?

Delta Airlines has not one but two documentaries about Jimmy Carter available to view: Carterland and Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President. (Do these movies make money? Who is funding them?) I was able to watch most of both of them (without sound, with subtitles) on recent transcontinental travels. Rock and Roll President was particularly interesting, for example how Carter did not turn on Gregg Allman even after he was busted for and then testified in a case involving pharmaceutical cocaine, or the role John Wayne played in helping the Panama Canal treaty to pass

All this has me to prepared to somewhat revise my view of Carter’s presidency. His inability to “do something” about the Iranian hostage crisis was because he was unwilling to start a war or kill a lot of innocent Iranians. Though his temperament may not have suited him to win reelection, he improved life in the United States, made a lot of difficult choices on tough problems, avoided war (Panama could’ve been one). His presidency was devoted to peace, and helped heal the United States.

The contradictions are endless but was it not good for us, in that moment, to have a prayerful man of peace and leadership that reached for the spiritual?

Similar to the way Gerald Ford was later honored for his courage (?) in pardoning Richard Nixon, should Jimmy Carter be honored for absorbing political consequences of hard decisions and hard efforts that kept the peace?

At the Carter Library the fact that Carter never dropped a bomb or fired a missile during his presidency is highlighted. He’s the last president of whom that can be said. The American people don’t seem to want that.

Perhaps his story is a Christian story, of the martyr, the saint, who suffers as he absorbs our sins. A traveling preacher who came to town.

Perhaps all post-1945 US presidents should be judged on one standard only: whether there was a nuclear war on their watch. We must give Carter an A!

In his Miller Center interview, Jimmy Carter notes several times that the governor of Georgia is very powerful – more powerful, relative to the legislature, than the president is to Congress:

Fenno

Mr. President, I just wanted to follow up one question about the energy preparation. In your book you note that when you came to present the energy package, you were shocked, I think the word was shocked, by finding out how many committees and subcommittees this package would have to go through.

Carter

Yes.

Fenno

I guess my question is in the preparation that you went through, didn’t Congressmen tell you what you were going to find? Why were you shocked?

Carter

Well, I don’t know if I expressed it accurately in the book. I don’t think it was just one moment when all of a sudden somebody came in the Oval Office and said there was more than one committee in the Congress that has got to deal with energy. I had better sense than to labor under that misapprehension. But I think when Tip O’Neill and I sat down to go over the energy package route through the House, I think Jim Wright was there also, there were seventeen committee or subcommittee chairmen with whom we would have to deal. That was a surprise to me, maybe shock is too strong a word. But in that session or immediately after that, Tip agreed as you know to put together an ad hoc committee, an omnibus committee, and to let [Thomas Ludlow] Ashley do the work.

That, in effect, short-circuited all those fragmented committees. The understanding was, after the committee chairmen objected, that when the conglomerate committee did its work, then the bill would have to be resubmitted, I believe to five different, major committees. There were some tight restraints on what they could do in the way of amendment. So that process was completed as you know between April and August, an unbelievable legislative achievement.

In the Senate though, there were two major committees and there had to be five different bills and unfortunately, Scoop Jackson was on one side and Russell Long was on the other. They were personally incompatible with each other and they had a different perspective as well. Scoop had been in the forefront of those who were for environmental quality and that sort of thing, and Russell represented the oil interest. That was one of the things that caused us a problem. But we were never able to overcome the complexities in the Senate. In the House, we did short circuit the process. I never realized before I got to Washington, to add one more sentence, how fragmented the Congress was and how little discipline there was, and how little loyalty there would be to an incumbent Democratic President. All three of those things were a surprise to me.

Truman

Were those in sharp contrast to the experience in the Georgia legislature?

Carter

Well, there’s no Democratic-Republican alignment of the Georgia legislature. It’s all Democrats, and therefore, there is no party loyalty. You had to deal with individual members. The Governor is really much more powerful in Georgia than the President is in the United States. As Georgia Governor, I had line-item veto, for instance, in the appropriations bills. And, as you also know, in Georgia and in Washington, most of the major initiatives come from the executive branch. There’s very seldom a major piece of legislation that ever originates in the legislature. I think that there is a parallel relationship between the independent legislature confronting an independent Governor or the independent Congress confronting an independent President. At the state level, the Governor, at least in Georgia, is much more powerful than the President in Washington.

Neustadt

Did you have the same kind of subcommittee structure?

Carter

No. It’s not nearly so complicated.

Neustadt

That helps you too.

Carter

The seniority and the guarding of turf and so forth is not nearly so much of a pork barrel arrangement in the state legislature. Also, the Georgia legislature only serves forty days a year. They come and do their work in a hurry, and then they go home.

Truman

A simple legislature doesn’t have much staff either.

Carter

They are growing rapidly in staff, but nothing like the Congress. And you don’t have the insidious, legal bribery in the Georgia legislature that is so pervasive in the Congress. That’s a problem that’s becoming much more serious and I don’t believe that it’s going to be corrected until we have a major, national scandal in the Congress. I think it’s much worse than most people realize.

The reviews all focus on the presidency but Carter was an extremely effective governor of Georgia.

wish I could read this redacted story:

The ex-presidency of Carter is often cited as admirable, the work on guinea worm is undeniable. James Baker contacted Carter frequently. He helped convince Daniel Ortega to leave office. But then:

In the run-up to the 1991 Gulf War, Carter’s relationship with President Bush turned sour. Carter felt passionately that Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait wasn’t worth going to war over, even though Bush cited the Carter Doctrine in justifying it. The former president said so publicly, then took matters a fateful step further, writing each member of the UN Security Council and urging them to vote against the United States on the resolution.

That is wild! Brian Mulroney told the Bush White House about it and they were unsurprisingly pissed!

The Carter/ Bill Clinton relationship is funny, Alter says Carter’s freelance riffing with North Korea made Clinton apoplectic. Bill and Jimmy, could make an almost not boring play.

Maybe I will stake out the take that Carter was a great president and a mixed bag as an ex-president. Could be fun!

Consider this:

In 2016, the squabbling children of Martin Luther King Jr. needed Carter to mediate. They were at one another’s throats over their family’s possessions, including an old pool table. Brothers Marty and Dexter teamed up to sue sister Bernice, who had possession of their father’s Bible (used by Barack Obama to take the oath of office) and his Nobel Peace Prize. Carter’s approach was the same as at Camp David: both sides would agree at the end of the process to one document. This time, the document went through six or seven drafts, with the parties finally agreeing that Carter’s decisions on what would be sold or kept were to be final. One night Carter would be hard on Bernice; the next, on Dexter or Marty. Carter finally determined — and a judge soon ratified that Marty, as chairman of the estate, had control of the Bible and the Nobel, but they would be displayed at the King Center in Atlanta, not sold.

The one document method might be something practical we can all learn from Jimmy Carter. I haven’t felt like time spent studying this American original has been wasted. The more I learn about him the more complex he becomes.

(photo of Dolly and Jimmy borrowed from Parton News instagram)

His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life by Jonathan Alter

Posted: December 31, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

If you’re wondering why he’s wearing watchface facing in, submariner’s habit, so you could tell time while working the periscope.

As a preteen he castrated hogs, ploughed a field with a mule (Emma), sheered sheep, pulled boil weevils from cotton by hand. By the time he was a teenager he was a slumlord, renting out tenant cabins to black farmers. After he graduated the Naval Academy he went to work for Admiral Rickover, who was inventing the nuclear navy. “Life is a constant fight against stupidity,” Rickover used to say. When the classified Chalk River Laboratories – National Research Experimental reactor nearly melted down, he led a group of twenty four who donned primitive “anti-C” suits and rehearsed removing as many flanges and turning as many valves as possible in an allotted ninety seconds before entering the contaminated space. Their urine and feces was examined for six months afterwards (they turned out to have no ill effects). When his father died, he agonized about what to do, but decided to quit the Navy and go back home without telling his wife, who was furious.

“No matter what happened – if it was a beautiful day or my older son made all As on his report card… underneath it was gnawing wawy because I owned twelve thousand dollars and didn’t know how I was going to pay it,” he would say about the next two years. Around this time he joined the Lions Club, as his father had:

Any time Jimmy wanted a toehold in some distant community, he would speak at one of Georgia’s 180 Lions Clubs, most in small towns.

He became obsessed with the poetry of Dylan Thomas, and it was his efforts that started a movement that led to a stone for Thomas being placed in Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey.

In Georgia at this time, there was a state requirement that busses carrying black kids to black schools had to have their fender painted black. Jimmy Carter was not a leader on integration. “This was a time, I’d say, of very radical elements on both sides,” he would say while he ran for president.

In 1962 the Supreme Court ruling in Baker v Carr enshrined a “one man, one vote” principle. Previously Georgia was organized on a “county unity system,” which meant Fulton County got only three times as many votes as a small rural county, even though it was 200x bigger.

Carter saw that by curbing the power of old courthouse politicians, Baker v. Carr would make a career in politics possible for a moderate like him.

The first time he ran for governor of Georgia he lost. “Show me a good loser and I’ll show you a loser,” was how he felt about that. He resolved to never lose another election. In 1970 he ran again, against Carl Sanders, who had helped bring major league baseball, football and basketball teams to Atlanta for the first time. Carter needed to win both racist George Wallace voters and liberal and black voters.

His solution was to avoid explicit mention of race in favor of class based populist appeals to Wallace voters, as well a overtures to moderates on education, the environment, and efficiency in government.

A research paper about southern populism by 25 year old Jody Powell affected his thinking. Powell would be a close aide all the way to the White House.

Carter shared his technique: “Notice how I didn’t ask for his vote. I said: ‘I want you to consider voting for me.'” At small and midsized campaign events, he would arrive early and park himself by the door so that he shook hands with every person entering the room – a simple and effective gesture neglected by many politicians.

During his inaugural speech as governor, he declared “the time for racial discrimination is over.” About a dozen conservative senators who had supported him walked out. But the speech got him on the cover of Time magazine.

During his term as governor he expected his team to work eighty and ninety hour weeks. He was aggressive, unrelenting, confrontational. Hunter S. Thompson would call Jimmy Carter one of the three meanest men he ever met – the other two being Muhammed Ali and Hells Angels president Sonny Barger.

“The conventional image of a sexy man is one who is hard on the outside and soft on the inside,” Sally Quinn wrote in the Washington Post. “Carter is just the opposite.”

When he ran for president his family was a tremendous advantage. During the Florida primary, Rosalynn and Edna Langford, her son’s mother-in-law, would drive into a town, look for the tallest antenna, and ask the station manager if someone wanted to interview them. Carter’s dynamic mother Lillian, who joined the Peace Corps at age sixty eight, would become a frequent guest on The Tonight Show.

Dick Cheney was working for Carter’s opponent Gerald Ford:

“Everybody knows about Plains Georgia and Lillian. Nobody really knows Ford,” Cheney wrote in a memo. “He never had a hometown. He never had a mother. He never had a childhood as far as the American people are concerned.”

Meanwhile:

Cutting the other way, Billy Carter crisscrossed Texas telling enthusiastic audiences that the Carers had always been conservatives, and that he would shoot Cesar Chavez, leader of the United Farm Workers of America union, if he came on his property.

It was a narrow win. If Ford hadn’t chucked Nelson Rockefeller, if Ford hadn’t said the thing in the debate about Eastern Europe, if.. if…

Exit polls showed that Carter won on pocketbook issues… The improbability of Carter’s victor struck speechwriter Rick Hertzberg who said later that electing him was as close “as the American people have every come to picking someone out of the phone book to be president.”

Hertzberg’s quote does not ring true to me. This was not a random guy. A nuclear engineer, a canny politician, a furious worker, a poet, rigid, deeply strange. As Alter says, comparing his post-presidency to the Clintons and Obamas, Carter was “built differently.” But then again Hertzberg knew him and I didn’t.

The parts of this book about the Carter presidency are mostly quite sad. Frustrations, bad luck, endless problems, prayers, defeats. An almost desperate search for spiritual answers, not even political ones. The great triumph, the Camp David Accords, took up enormous amounts of time and energy. Sadat had already visited Jerusalem, were Israel and Egypt on the road to peace anyway? I don’t know enough about it.

A good man, but not a good president, was and is a widely held opinion. Was he not a good president because he was a good man? Does dealing with the Ayatollah (or Congressional committee chairs) require a nasty operator on the level of Johnson or Nixon? Consider Reagan’s team, who got their hands on Carter’s debate prep book, and almost certainly cut a secret deal with the Iranians that involved selling weapons for the war with Iraq which killed more than a million people.

Was Carter caught between the pious Sunday school teacher and the tough engineer with not enough of the jolly, dealmaking, wink and a handshake stuff you need in our system?

Carter vocally committed the US to “human rights” as president. The resulting hypocrisies are not hard to spot. The Carter administration was effectively advising the Shah of Iran to shoot protestors, to take one example. Can human rights really be a presidential interest in this soiled world?

Can a true follower of Jesus ever be an effective US president?

Maybe the biggest way the Carter presidency ripples through daily life in 2025: deregulation. Trucking, rail, airlines, natural gas. Southwest Airlines, Wal-Mart, Amazon, the shale boom, none of these would be the same without Carter-era deregulation. The consequences are many and mixed, and the result may not have matched the vision. The main stated goal was to fight inflation, massive problem and major part of Carter’s undoing.

Biographies have to make the case for the subject’s significance (otherwise why am I reading?). So they might be biased towards showing a master shaping events. Alter’s Carter doesn’t come off like that, he seems blown about by winds beyond his control.

The book is great by the way, I was very absorbed. Something I should learn more about would be Carter’s relationship to unions, organized labor. In Passage of Power Caro, reporting on LBJ’s first presidential weekend mentions several calls with labor leaders like Walter Reuther. By the next Democratic presidency I hear almost nothing about labor. Jimmy was a business owner, manager and employer. Georgia was not a union friendly state. Maybe there’s a bigger story to be told about the collapse of US labor power between 1963 and 1976. Maybe Carter is a part of that story.

While he was governor Carter launched the Georgia Film Commission, which has had a significant impact on my life, as my friends are always flying to Atlanta to shoot stuff. Los Angeles is being outcompeted as a filming location.

Carter was friends with James Dickey, and helped arrange Georgia as a shooting location for Deliverance and The Longest Yard (using Georgia inmates).

On a recent visit to Atlanta* I had a chance to visit the Carter Library. I thought I might buy my daughter a present at the gift shop. After all, at the Reagan Library the gift shop is enormous, mugs, toys, models, posters, DVDs. At the Carter Library, not so:

Very sparse, not even all of Jimmy’s books.

There’s a replica of the Oval Office as it existed in Carter’s time. A recording of Carter says that tough, strong-willed people he’d known in Georgia would come to see him in the Oval Office, and the aura of the room would strike them dumb, they’d forget what they came to see him about.

I was very struck by this photo of Amy:

So vulnerable.

*Trip unrelated to Georgia Film Commission, although related to the Ted Turner cable empire, a tentacle of which will air Common Side Effects, premiering Feb. 2, 11:30pm, first airing on Cartoon Network/Adult Swim, streaming on Max next day. Don’t miss!

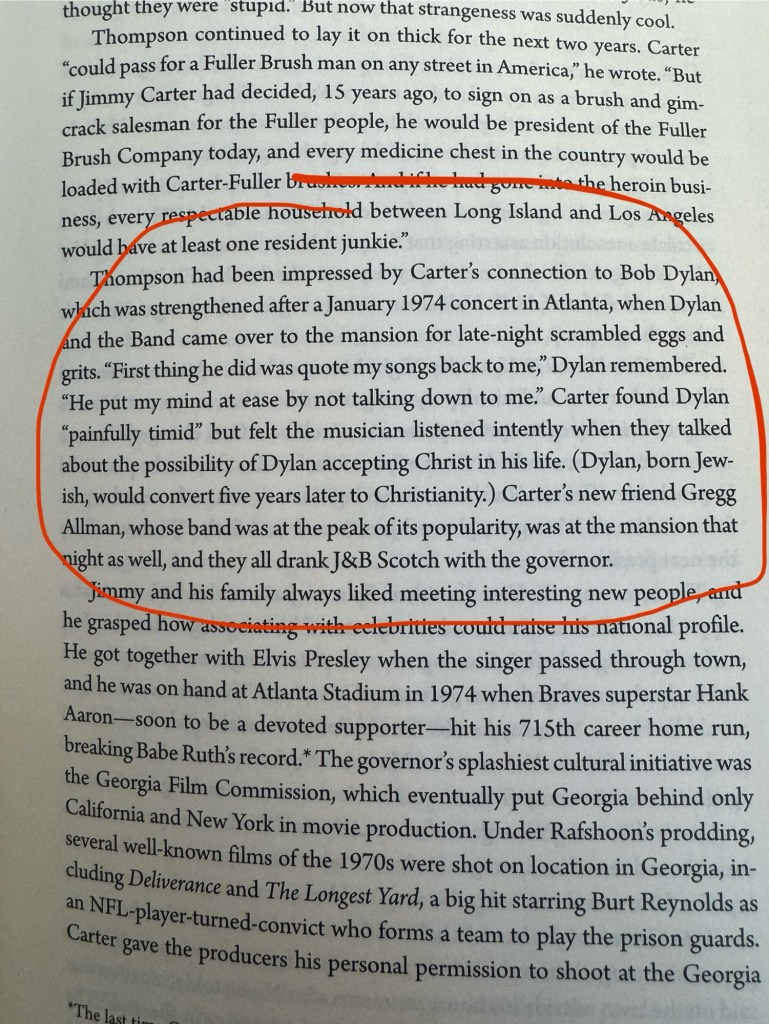

Jimmy Carter and Bob Dylan

Posted: December 8, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a commentJimmy Carter bonded with his son Chip over Dylan:

In 1969 Chip and his father hadn’t spoken for a year, mostly because of Chip’s drug use. They reconnected through Bob Dylan, whose album The Times They Are A-Changin’ they had enjoyed together. “We talked on the phone in Dylan verses because of the tensions,” Chip remembered. Struggling at Georgia Southwestern, Chip drove home to Plains at two in the morning, went to the foot of his parents’ bed, and informed them he was addicted to speed. Jimmy’s response was to tell his nineteen-year-old son to cut his hair, put away his bell-bottom jeans, and buy a suit. After promoting Powell, he assigned Chip to be his part-time driver in the campaign; that way, he could be with him often enough to make sure he wasn’t abusing drugs. Chip’s decades of substance abuse had only begun, but he said later that his parents’ intervention in 1969 saved his life.

Talking to Hunter S. Thompson:

The governor first impressed Thompson when he said that after theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, “the other source of my understanding about what’s right and wrong in this society is from a friend of mine, a poet named Bob Dylan.” He explained, “I grew up a landowner’s son. But I don’t think I ever realized the proper relationship between the landowner and those who worked on the farm until I heard Dylan’s record ‘I Ain’t Gonna Work on Maggie’s Farm No More?” Carter’s easy familiarity with Dylan’s work would harvest young votes once the 1976 primaries began.

Dylan enthusiasm culminated in a meeting while Carter was governor of Georgia:

From Jonathan Alter, His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life. I shared this story with Dylan enthusiast Vali, who told me posting it would be a service to the Dylan community. But the Dylan community being what it is, all connections to Carter are thoroughly covered in a post on flaggingdown.com, where I find this photo of Chip, Dylan, Jimmy and Jeff Carter.

Concerts became an important part of Carter’s early presidential campaign. It was not Dylan but another musician Carter considered indispensible:

October 1975 was when the campaign began to cohere. Rafshoon filmed Carter in a Florida pulpit and turned the sermon into two ads that began running in Iowa. Because each spot was five minutes long, Iowa voters saw them as news pieces, and they began breaking through. In the ads, Carter says, “T’ll never tell a lie. I’ll never make a false statement. I’ll never betray the confidence you have in me, and I won’t avoid a controversial issue. Watch television. Listen to the radio. If I do any of those things, don’t support me.” The ads were paid for in part by a series of inspired concerts arranged by the “godfather of rock” Phil Walden, president of Capricorn Records and a friend of Carter from Georgia. The first, by the Marshall Tucker Band, was held at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre. Soon Carter would raise money with the help of Charlie Daniels, Willie Nelson, Lynyrd Skynyrd, John Denver, Jerry Jeff Walker, Jimmy Buffett, and the Allman Brothers.* “If it hadn’t been for Gregg Allman, I never would have been president,” Carter said after Allman died in 2017.

The political risks of being associated with a druggy counterculture never concerned the candidate, even when he saw handmade “Coke Fiends for Carter” signs at his rallies. His admiration of the long-haired musicians was real and reciprocated, with many saying later that they felt a deep, almost mystical connection to him. And the fund-raising advantage offered by the rock concerts was significant. Each ticket stub was used as a receipt to show a contribution that could later be used for matching federal campaign funds.

Carter was also pals with Elvis. Elvis called Carter on the phone one day at the White House, apparently fucked up, shortly before he died.

Carter was smart at these concerts:

Carter understood just what to do onstage. “I’m gonna say four things,” he said at a rock concert in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1975. “First of all, I’m running for president. Secondly, I’m gonna be elected. Third, this is very im-portant, would you help me? Fourth, I want to introduce to you, my friends and your friends, the great Allman Brothers!” This was followed by thunderous applause. A politician who knew better than to make a speech at a rock concert was guaranteed to win the votes of thousands of grateful fans.

Lonely California slough

Posted: November 30, 2024 Filed under: the California Condition Leave a comment

Norms

Posted: November 30, 2024 Filed under: the California Condition, Uncategorized Leave a commentI read that Norms on La Cienega, a classic LA diner, may be replaced by a Raising Cane’s.

This Norm’s is the subject of a famous painting by Ed Ruscha:

I asked different AIs to generate some versions of this painting if it were a Cane’s instead of a Norm’s.

From The LA Times:

[Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson with U.S. Representative Victor Anfuso and his daughter (right) at a party at the Shoreham Hotel, Washington, D.C.] / MST. digital file from original

Posted: November 18, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

source. I’ve been listening to Caro’s Years of Lyndon Johnson: Passage of Power. Very calming in a way.

Caro makes much of the cruel “Rufus Cornpone” nickname (although he never says who made that up). JFK had his own nickname for LBJ. He called him “Riverboat.”

A tactic LBJ used was getting people to feel sorry for him:

Having observed Johnson close up for more than twenty years, Rowe was aware, he says, that Johnson would always use “whatever he could” to “make people feel sorry for him” because “that helped him get what he wanted from them.” But that awareness didn’t help Rowe when, in 1956, the person from whom Johnson wanted something was him. Having observed also how Johnson treated people on his payroll, he had for years been rejecting Johnson’s offers to join his staff, and had been determined never to do so. But Johnson’s heart attack in 1955 gave him a new weapon—and in January, 1956, he deployed it, saying, in a low, earnest voice, “I wish you would come down to the Senate and help me.” And when Rowe refused, using his law practice as an excuse (“ I said, ‘I can’t afford it, I’ll lose clients’ ”), Johnson began telling other members of their circle how cruel it was of Jim to refuse to take a little of the load off a man at death’s door. “People I knew were coming up to me on the street—on the street—and saying, ‘Why aren’t you helping Lyndon? Don’t you know how sick he is? How can you let him down when he needs you?’ ”

Johnson had spoken to Rowe’s law partner, Rowe found. “To my amazement, Corcoran was saying, ‘You just can’t do this to Lyndon Johnson!’ I said, ‘What do you mean I can’t do it?’ He said, ‘Never mind the clients. We’ll hold down the law firm.’ ” Johnson had spoken to Rowe’s wife. “One night, Elizabeth turned on me: ‘Why are you doing this to poor Lyndon?’ ”

Then Lyndon Johnson came to Jim Rowe’s office again, pleading with him, crying real tears as he sat doubled over, his face in his hands. “He wept. ‘I’m going to die. You’re an old friend. I thought you were my friend and you don’t care that I’m going to die. It’s just selfish of you, typically selfish.’ ”

Finally Rowe said, “Oh, goddamn it, all right”—and then “as soon as Lyndon got what he wanted,” Rowe was forcibly reminded why he had been determined not to join his staff. The moment the words were out of Rowe’s mouth, Johnson straightened up, and his tone changed instantly from one of pleading to one of cold command. “Just remember,” he said. “I make the decisions. You don’t.”

Amazing. But:

Now this technique was used with Jack Kennedy. At meetings, the soft voice was coupled with a face that varied between sullen and sorrowful—the look of a very sad man. And if pressed particularly pointedly by the President for an explanation or a recommendation, he would say, “I’m not competent to advise you on this,” sometimes adding that he didn’t have enough information on the subject, statements that Kennedy viewed, in Sorensen’s phrase, as being Johnson’s “own subtle way of complaining to the President” about his treatment. With Kennedy, however, the tactic had no success at all. “I cannot stand Johnson’s damn long face,” the President told his buddy Smathers. “He just comes in, sits at the Cabinet meetings with his face all screwed up, never says anything. He looks so sad.… You’ve seen him, George, you know him, he doesn’t even open his mouth.” Smathers suggested foreign travel. “You ought to send him on a trip so that he can get all of the fanfare and all of the attention … build up his ego again, let him have a great time”—and also, although Smathers didn’t say it, get him out of Kennedy’s hair. “You know, that’s a damn good idea,” Kennedy replied—and at the beginning of April sent him to Senegal, which was celebrating the first anniversary of its independence.”

Here they are the return from that trip. The man in the middle is listed as “Unidentified.”

A galled crotch

Posted: November 13, 2024 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

Reading at last J. Evetts Hayley’s biography of Charles Goodnight.

Querencia

Posted: November 3, 2024 Filed under: Mexico, sports Leave a comment

The first page of Proust: I woke up, and I never knew in the beginning where I was, so I went through all the bedrooms of my life. The way I think of it is like a Disney film. First, you think it was better when you were seven years old, and furniture looked a certain way. Then you think, no, it was best when you were twelve, so all the chairs dance around and restructure themselves into the bedroom you had when you were twelve. Finally, you reach your current age, and, here, they find their places in yet a different arrangement. Territorialization works in this way. In music, the refrain is making that home for yourself in music by territorializing sound through repetition.

What does it mean to have a home?

I don’t know whether any of you have seen bullfights; maybe you think they are horrible, or maybe you are interested in death, like Hemingway. In a bullfight, the bull emerges out into a world which is completely unfamiliar. The bull must then territorialize this world, so he finds a part of the bull ring—it’s arbitrary, because the space is all the same-which will be his terrain. In bullfighting language, this is called the querencia, from querer.

This space belongs to the bull. None of the actors in the bullfight, and especially not the matador, will ever try to get into that place. They have to identify it, because there the bull is supreme. They have to lure it out of its querencia in order to fight it in some other place. All of this is in Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon, his book on the bullfight. As he says, he was interested in the bullfight because, as a writer, he wanted to know what death was, and the bullfight often results in the deaths of the bulls and also of the mata-dors. But you can see the usefulness of understanding territorialization as your querencia, the way you naturalize, normalize, make your own space, space being understood in the sense of the plane of immanence, that is to say, the connections of all these things. Some are interests or pas-sions; some are objects, tasks, or habits. All that you organize into something which I guess you call your identity, but it isn’t your identity; it is your territorialization, and you are caught in it. For the infant, that will be the parents. Why do you think Deleuze and Guattari attack Freud and the Oedipus complex? Who wants to be caught with their parents their whole life?

You want to get away from them. Kristeva and Irigaray’s description of the mother:

You have to get away. You have to deterritorialize.

And now another crucial Deleuzean ex-pression: the line of flight. You must try to invent lines of flight out of your territory, because your territory is going to be taken over by Google, by General Motors, by Coca-Cola. It will lie in the globalized world of the great corporations. It doesn’t belong to you anymore. You can try to make a little space that you call your own, and that will be what Deleuze calls your secret garden.

that from Jameson’s Years Of Theory.

Dry Head and Bloody Bones

Posted: October 31, 2024 Filed under: America | Tags: writing Leave a commentAn American horror story for this Halloween:

On November 20, 1936, in Jacksonville, FL a WPA field worker named Rachel Austin interviewed a former enslaved person named Florida Clayton (she was given that name as the first in her family born in that state).

The rest of this story is too upsetting to reprint, it can be found in The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, volume 17, Florida Narratives, reprinted 1972. Or here.

Dry Head and Bloody Bones. If you go poking into American history you’ll find some scary stuff!

Be safe out there this Halloween! 🎃

I doubt it but I’d like to meet him

Posted: October 30, 2024 Filed under: hely | Tags: Helys Leave a comment

Or her!

Ballot

Posted: October 29, 2024 Filed under: the California Condition 2 Comments

Donald Trump is pure toxicity, he tried half-seriously to end the peaceful transfer of power, he’s beyond unacceptable. We endorse native daughter of the Golden State Kamala Harris and hope that a special Providence continues to look after children, drunks, and the United States.

I put this together for my own use, perhaps it is useful to you, much cribbed from The LA Times. I’ll be voting in person in a few days so feel free to make a strong case I am open to persuasion on city, state and county measures.

Community College, Seat 1: Andra Hoffman

Community College, Seat 3: David Vela

Community College, Seat 5: Nichelle Henderson

Community College: Seat 7: Kelsey Iino

US Rep: Laura Friedman

City Measure DD: Yes

City Measure HH: Yes

City Measure II: Yes

City Measure ER: Yes

City Measure FF: Yes (on the fence here, it’s expensive, but I go with Mayor Bass)

City Measure LL: Yes

Uni Measure US: Yes

District Attorney: Nathan Hochman (both bad options here, voting to express disgust.)

It makes me a little mad that I have to vote for judges. I found this helpful.

Judge No 39: Steve Napolitano

Judge No. 48: Ericka Wiley (I don’t see anything wrong with Renee Rose)

Judge No. 97: Sharon Ransom

Judge No. 135: Steven Yee Mac (nothing wrong with Georgia Huerta)

Judge No. 137: Tracey Blount

County Measure G: Yes

County Measure A: Yes