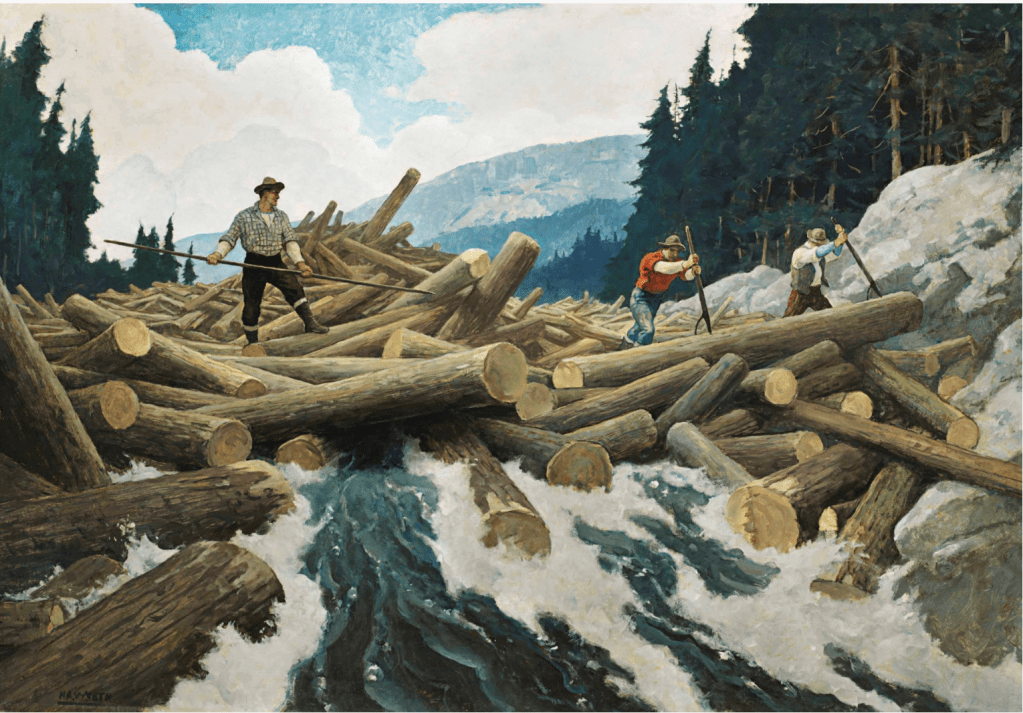

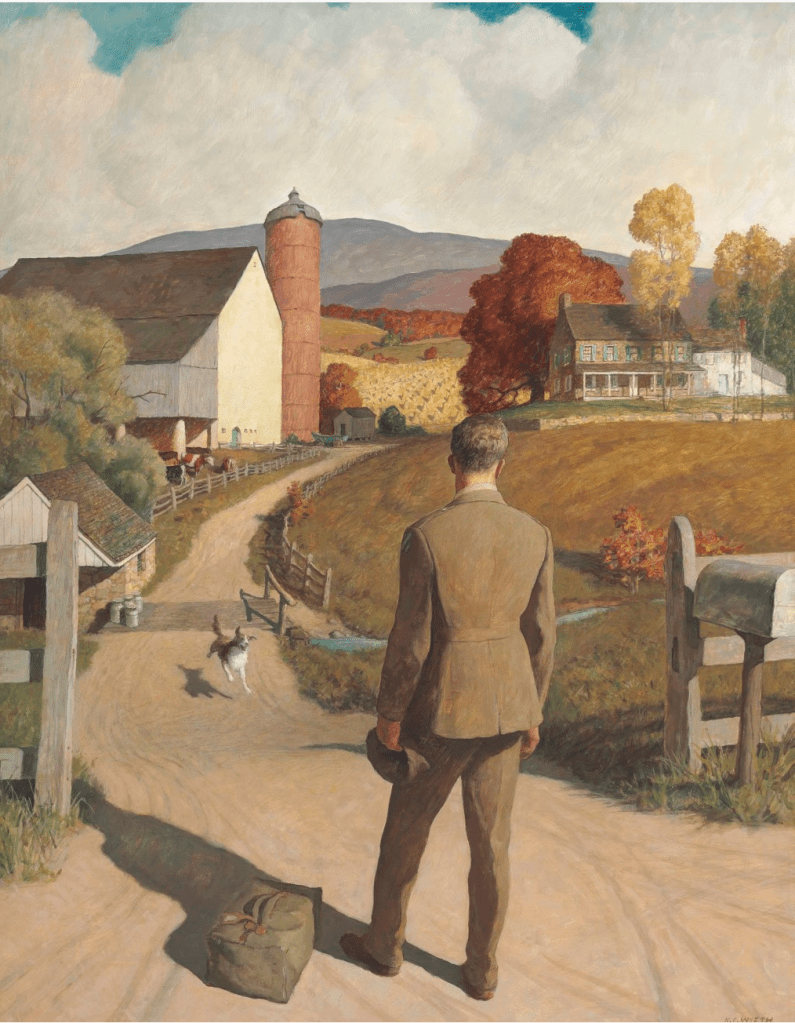

N. C. Wyeth

Posted: January 26, 2026 Filed under: art history 1 CommentSeeing what the son of Needham’s paintings were fetching lately at auction (high six-low seven figures).

more here.

A potential cover of Ramona:

The Lac d’Annecy by Paul Cezanne

Posted: May 24, 2025 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

Cézanne painted this work while on holiday in the Haute-Savoie in 1896, writing dismissively of the conventional beauty of the landscape as “a little like we’ve been taught to see it in the albums of young lady travellers”. He rejected such conventions, seeking not to replicate the superficial appearance of the landscape but to express what he described as a “harmony parallel with nature” through a new language of painting.

In his essay “Cezanne’s Doubt” (mentioned by Jameson in Years of Theory) Maurice Merleau-Ponty says:

We live in the midst of man-made objects, among tools, in houses, streets, cities, and most of the time we see them only through the human actions which put them to use. We become used to thinking that all of this exists necessarily and unshakably. Cezanne’s painting suspends these habits of thought and reveals the base of inhuman nature upon which man has installed himself. This is why Cezanne’s people are strange, as if viewed by a creature of another species. Nature itself is stripped of the attributes which make it ready for animistic communions: there is no wind in the landscape, no movement on the Lac d’Annecy; the frozen objects hesitate as at the beginning of the world. It is an unfamiliar world in which one is uncomfortable and which forbids all human effusiveness. If one looks at the work of other painters after seeing Cezanne’s paintings, one feels somehow relaxed, just as conversations resumed after a period of mourning mask the absolute change and restore to the survivors their solidity. But indeed only a human being is capable of such a vision, which penetrates right to the root of things beneath the imposed order of humanity. All indications are that animals cannot look at things, cannot penetrate them in expectation of nothing but the truth. Emile Bernard’s statement that a realistic painter is only an ape is therefore precisely the opposite of the truth, and one sees how Cezanne was able to revive the classical

definition of art: man added to nature

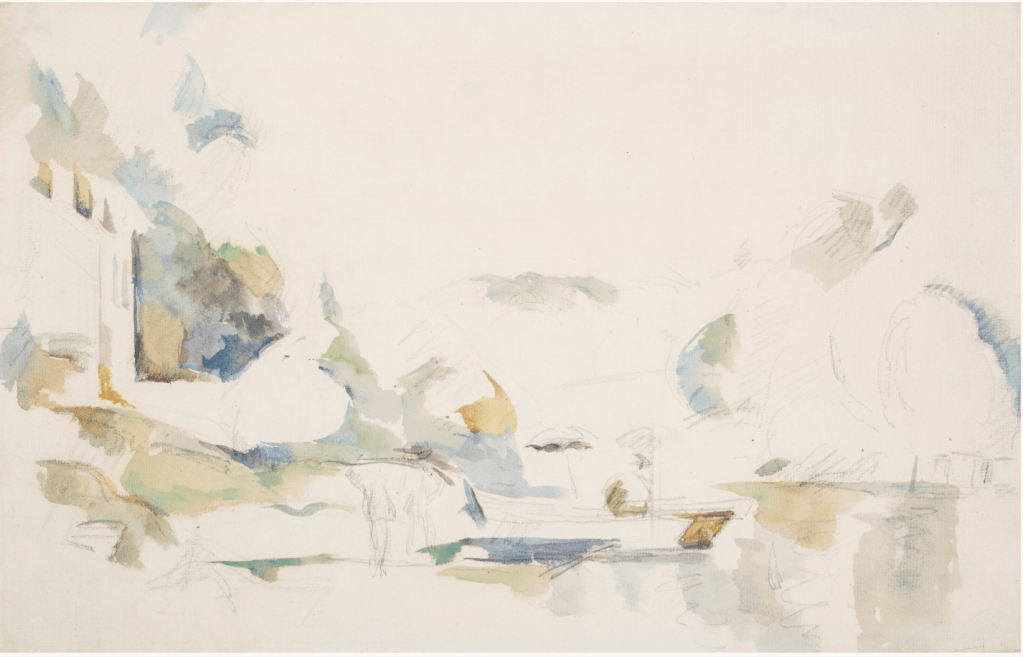

Looking into Annecy by Cezanne I also find this, La Barque ou Le Lac d’Annecy, which Christie’s sold for $403,200 USD

Here’s an intriguing essay by Jeffrey Meyers on Hemingway and Cezanne. In several places Hemingway said he wanted to write like Cezanne painted:

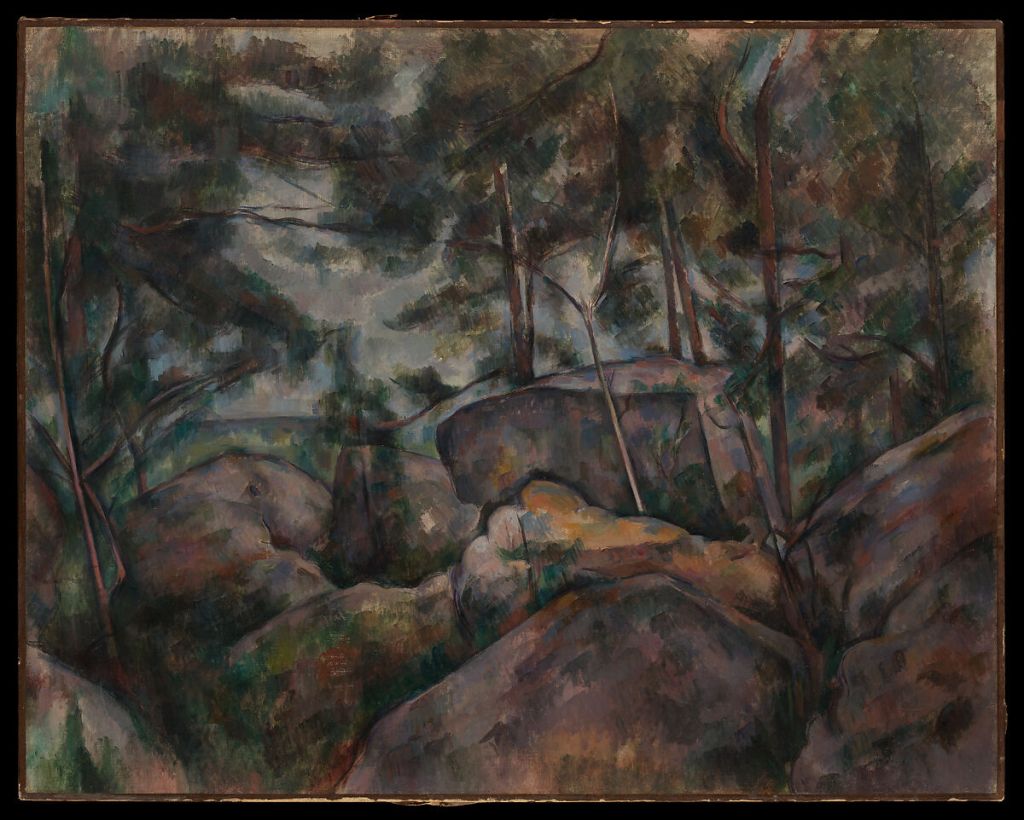

Hemingway spent several minutes looking at Cezanne’s “Rocks – Forest of Fontainebleu.” “This is what we try to do in writing, this and this, and the woods, and the rocks we have to climb over,” he said. “Cezanne is my painter, after the early painters. Wonder, wonder painter…

As we walked along, Hemingway said to me, “I can make a landscape like Mr. Paul Cezanne. I learned how to make a landscape from Mr. Paul Cezanne by walking through the Luxembourg Museum a thousand times with an empty gut, and I am pretty sure that if Mr. Paul was around, he would like the way I make them and be happy that I learned it from him.”

What does it mean to write like Cezanne painted? In his essay Merleau-Ponty quotes Cezanne in a way that gives a clue:

Nor did Cezanne neglect the physiognomy of objects and faces: he simply wanted to capture it emerging from the color. Painting a face “as an object” is not to strip it of its “thought.” “I agree that the painter must interpret it,” said Cezanne. “The painter is not an imbecile.” But this interpretation should not be a reflection distinct from the act of seeing. “If I paint all the little blues and all the little browns, I capture and convey his glance. Who gives a damn if they have any idea how one can sadden a mouth or make a cheek smile by wedding a shaded green to a red.” One’s personality is seen and grasped in one’s glance, which is, however, no more than a combination of colors. Other minds are given to us only as incarnate, as belonging to faces and gestures. Countering with the distinctions of soul and body, thought and vision is of no use here, for Cezanne returns to just that primordial experience from which these notions are derived and in which they are inseparable. The painter who conceptualizes and seeks the expression first misses the mystery— renewed every time we look at someone—of a person’s appearing in nature. In La peal de chagrin Balzac describes a “tablecloth white as a layer of fresh-fallen snow, upon which ,the place settings rose symmetrically, crowned with blond rolls.” “All through my youth,” said Cezanne, “I wanted to paint that, that tablecloth of fresh-fallen snow…. Now I know that one must only want to paint’rose, symmetrically, the place settings’ and ‘blond rolls.’ If I paint ‘crowned’ I’m done for, you understand? But if I really balance and shade my place settings and rolls as they are in nature, you can be sure the crowns, the snow and the whole shebang will be there.”

This effort did not make for an easy life for Cezanne:

Occasionally he would visit Paris, but when he ran into friends he would motion to them from a distance not to approach him. In 1903, after his pictures had begun to sell in Paris at twice the price of Monet’s and when young men like Joachim Gasquet and Emile Bernard came to see him and ask him questions, he unbent a little. But his fits of anger continued. (In Aix a child once hit him as he passed by; after that he could not bear any contact.)

…nine days out of ten all he saw around him was the wretchedness of his empirical life and of his unsuccessful attempts, the debris of an unknown celebrations

The closest Hemingway gets to saying something similar? Maybe it’s this, from an Esquire article, “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter,” October 1935, that’s in the form of a dialogue with an apprentice:

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise. Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Then get in somebody elseʼs head for a change If I bawl you out try to figure out what Iʼm thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Donʼt just think who is right. As a man things are as they should or shouldnʼt be. As a man you know who is right and who is wrong. You have to make decisions and enforce them. As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.

Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

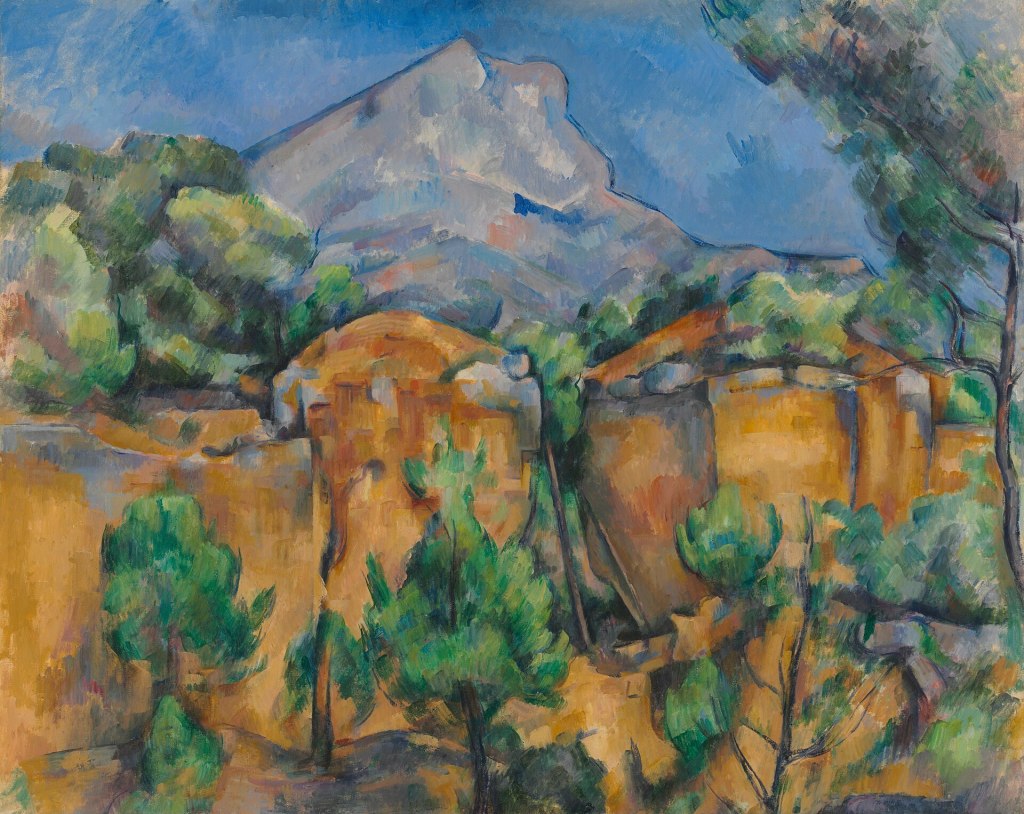

Cezanne left Annecy and went back to painting his Mont Saint-Victoire:

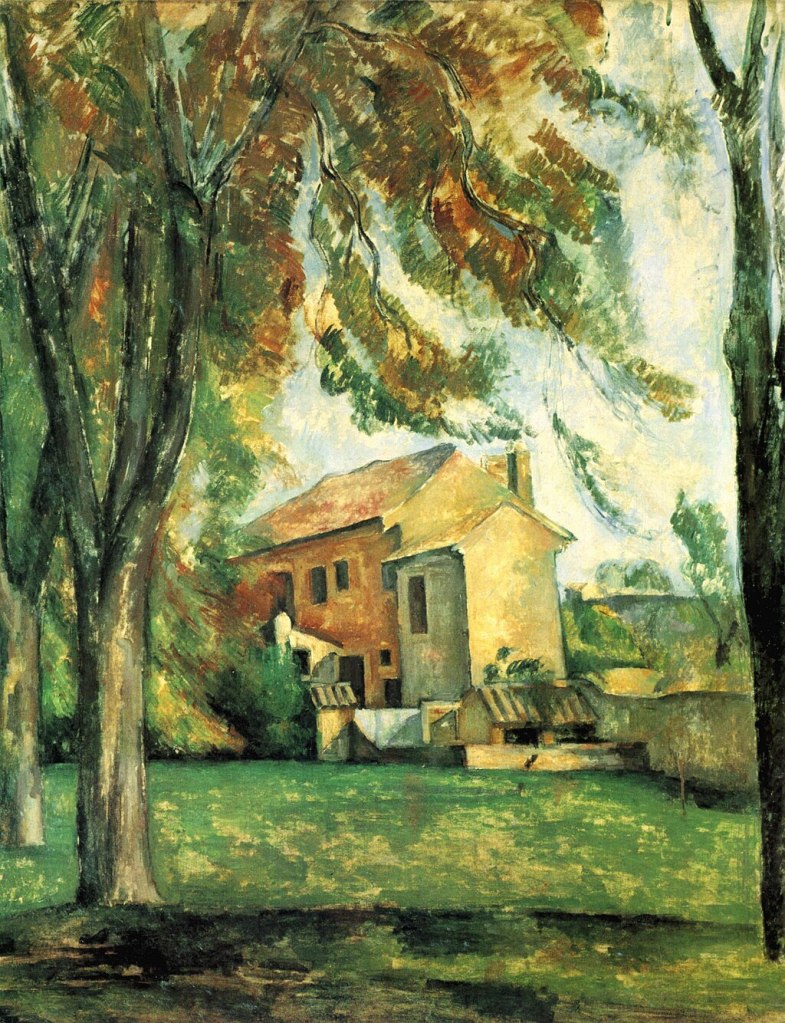

There are four Cezannes at the Norton Simon Museum, right down the street from where I’m typing this:

a couple at the Getty, one at the Hammer, and a classic at LACMA:

although that one’s not on display right now.

More on Cezanne.

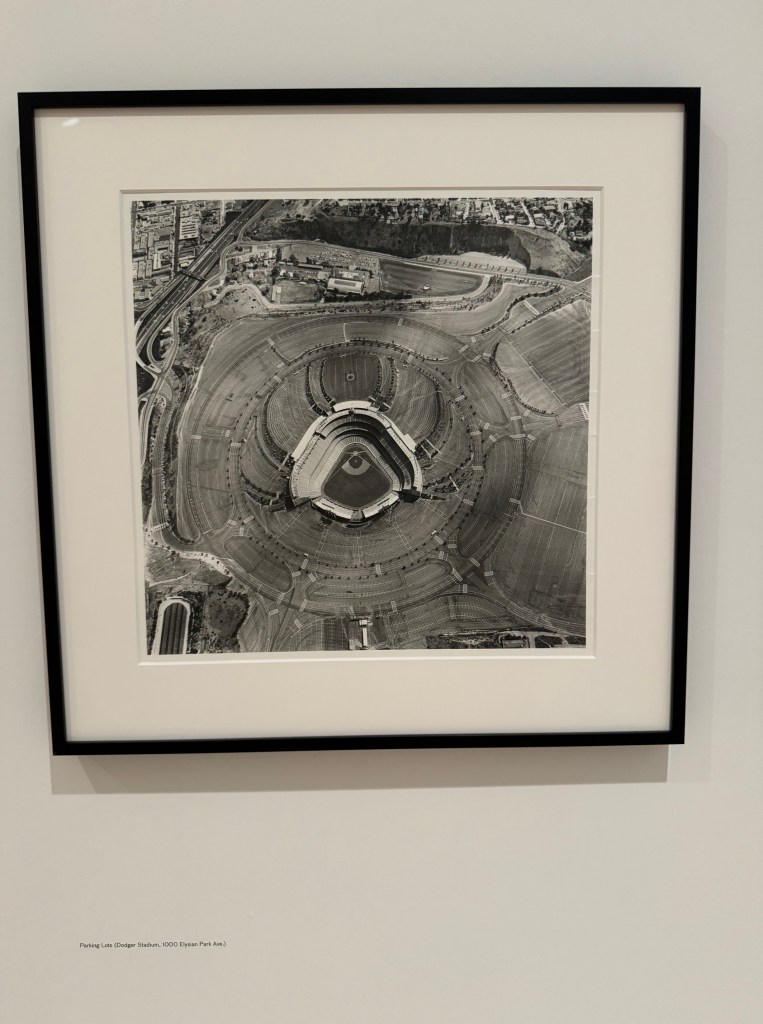

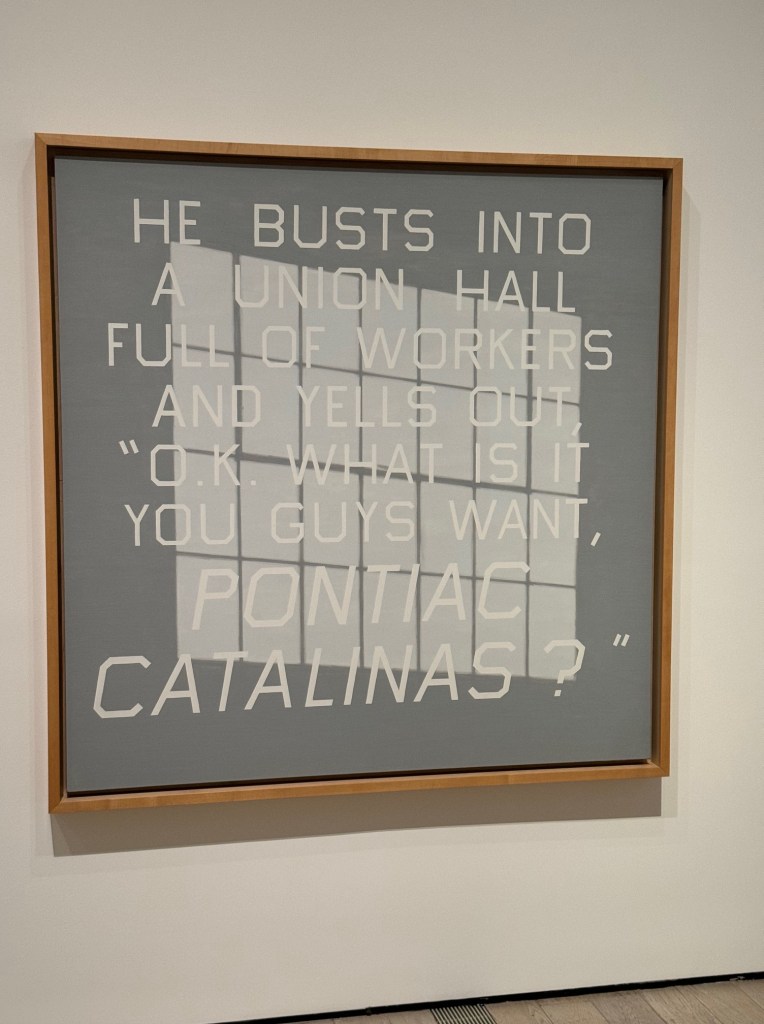

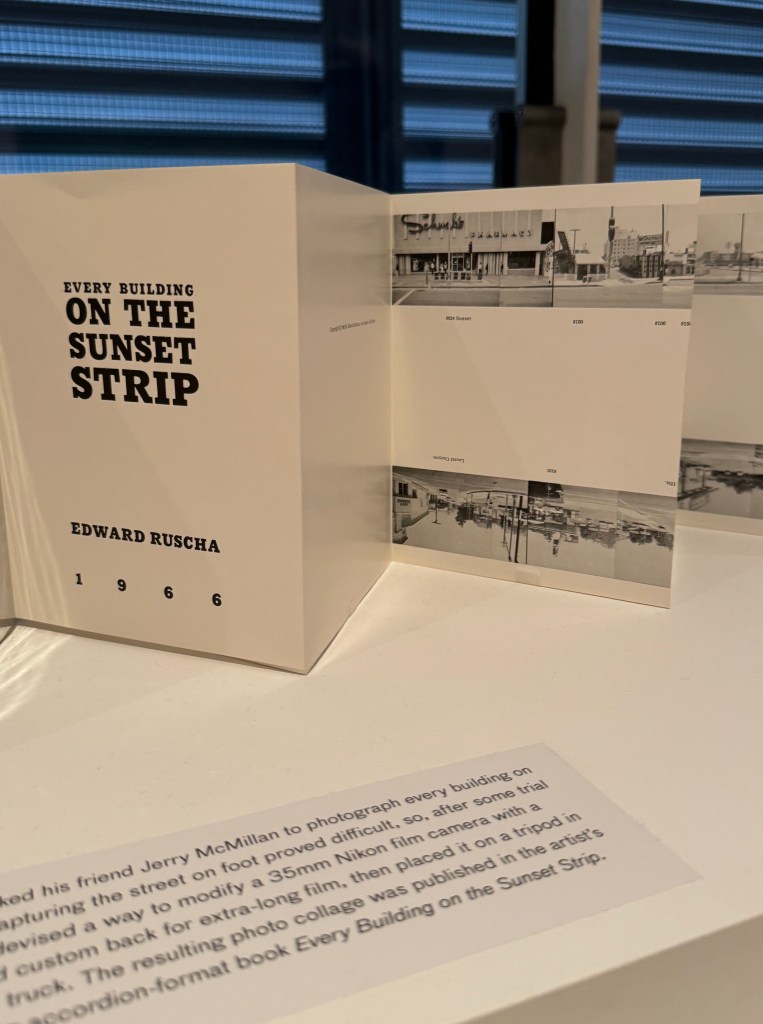

Ed Ruscha at LACMA

Posted: July 10, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history Leave a commentThe Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, 1968

photo taken in Ireland, 1962:

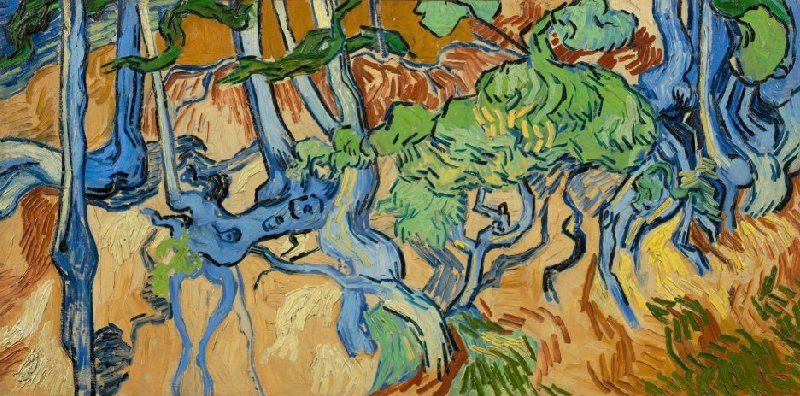

Tree Roots

Posted: February 12, 2023 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

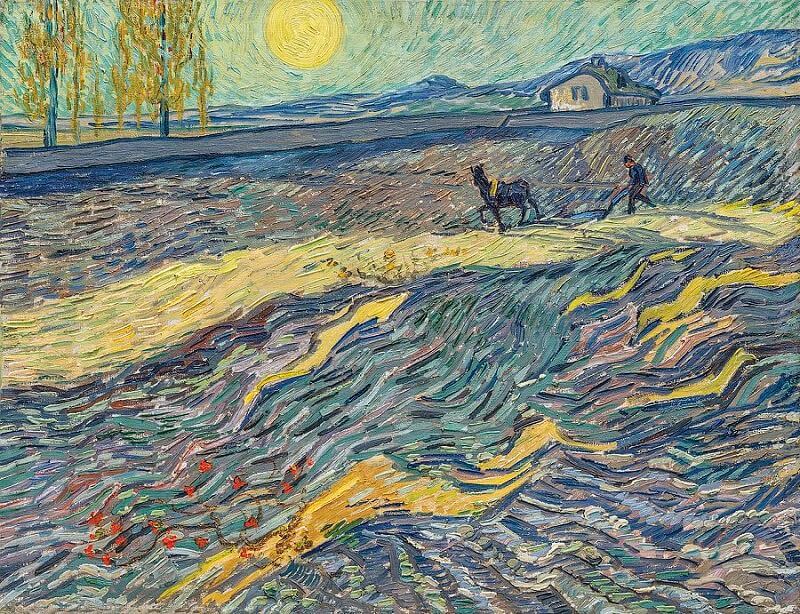

Van Gogh’s last painting.

a personal VVG favorite is Enclosed Field with Ploughman, the view from his room at the mental asylum. Currently at the MFA in Boston.

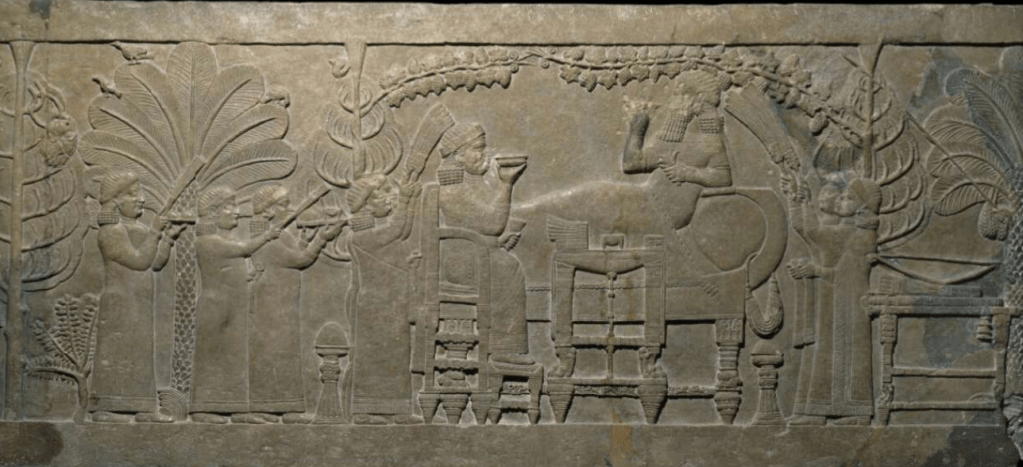

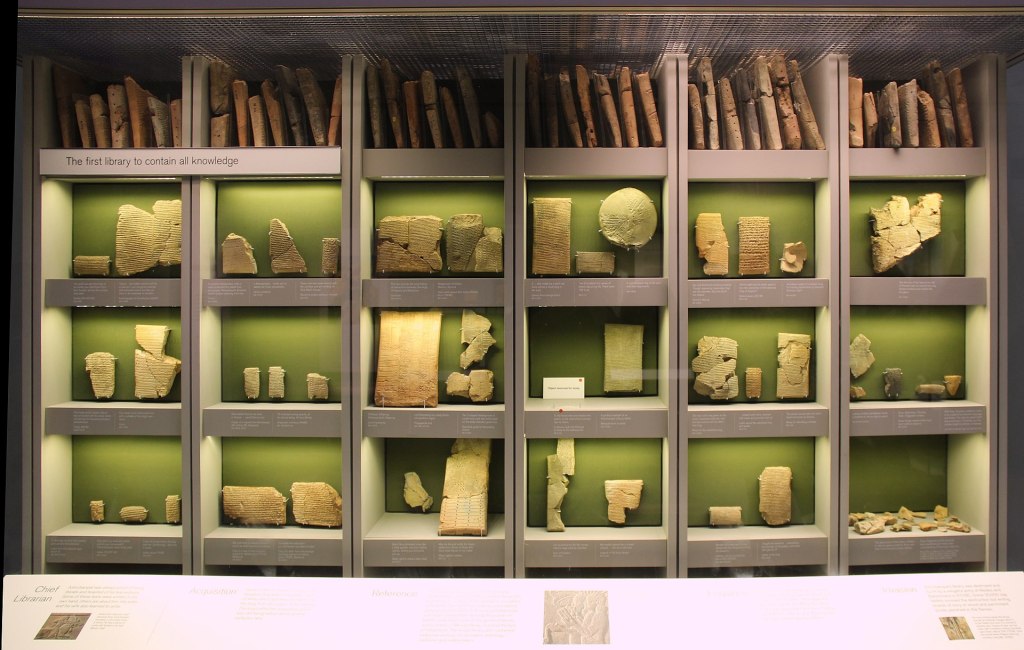

Ashurbanipal

Posted: September 14, 2022 Filed under: art history Leave a commentIn this relief, created around 645 BCE or so, excavated two thousand four hundredsome years later in 1853 or so in what’s now Iraq, brought to The British Museum, we see the ruler Ashurbanipal lounging and listening to tunes while to the left the decapitated head of Teumman, king of Elam, hangs from a tree.

Ashurbanipal was a rough guy. Also at The British Museum you can find this relief of his dudes flaying and torturing captured Elamites:

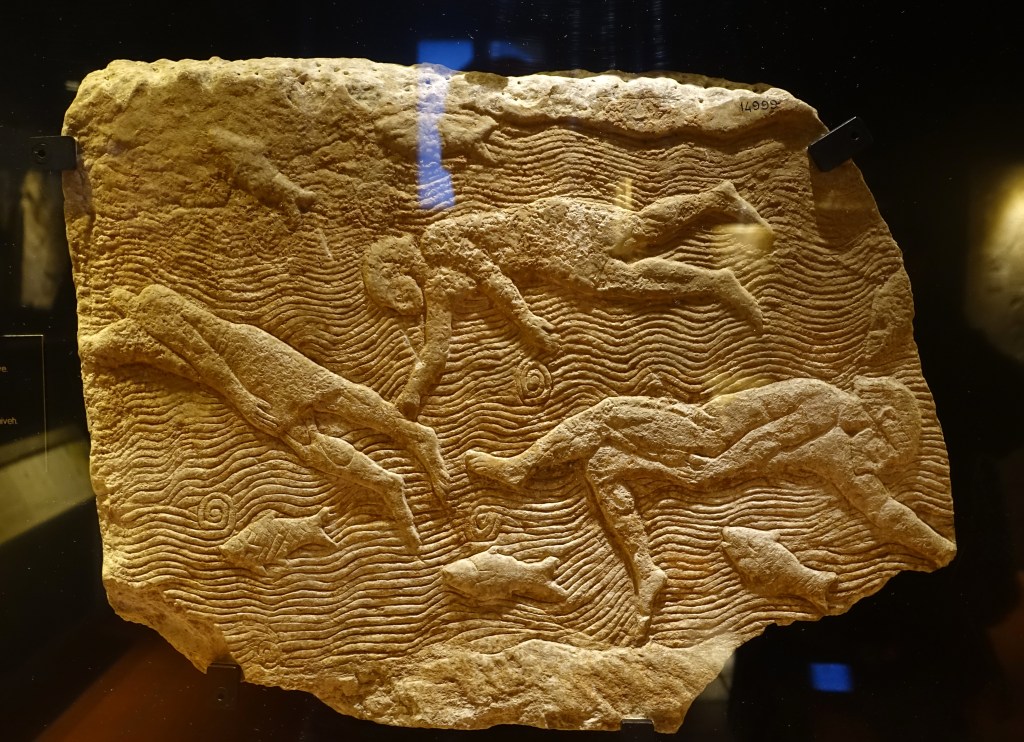

And at the Vatican Museum they’ve got one of bodies floating in the river flowing his arrival somewhere:

But Ashurbanipal did create a magnificent library, which (of course) they’ve hauled off to The British Museum as well.

In the library was a tablet that told some of the story of Gilgamesh, including an account of a great flood. It’s said that when George Smith was translated this tablet, and realized what he’d found, he started shouting and taking his clothes off.

Warhol/Rothko

Posted: September 1, 2022 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

from a profile of Dana White of UFC in the Financial Times. Pretty interesting article, actually: White claims he left Boston for Nevada after Whitey Bulger goons demanded $2,500 in shakedown money. And:

He says there are three main types of people in the world: nerds, jocks and stoners, none of whom truly understand the others. There’s also a small fourth group: fighters. They’re outsiders who lack social skills and operate on a base level. As a kid, he thought he might be one.

(I disagree, I think most people are a blend, but fun system.)

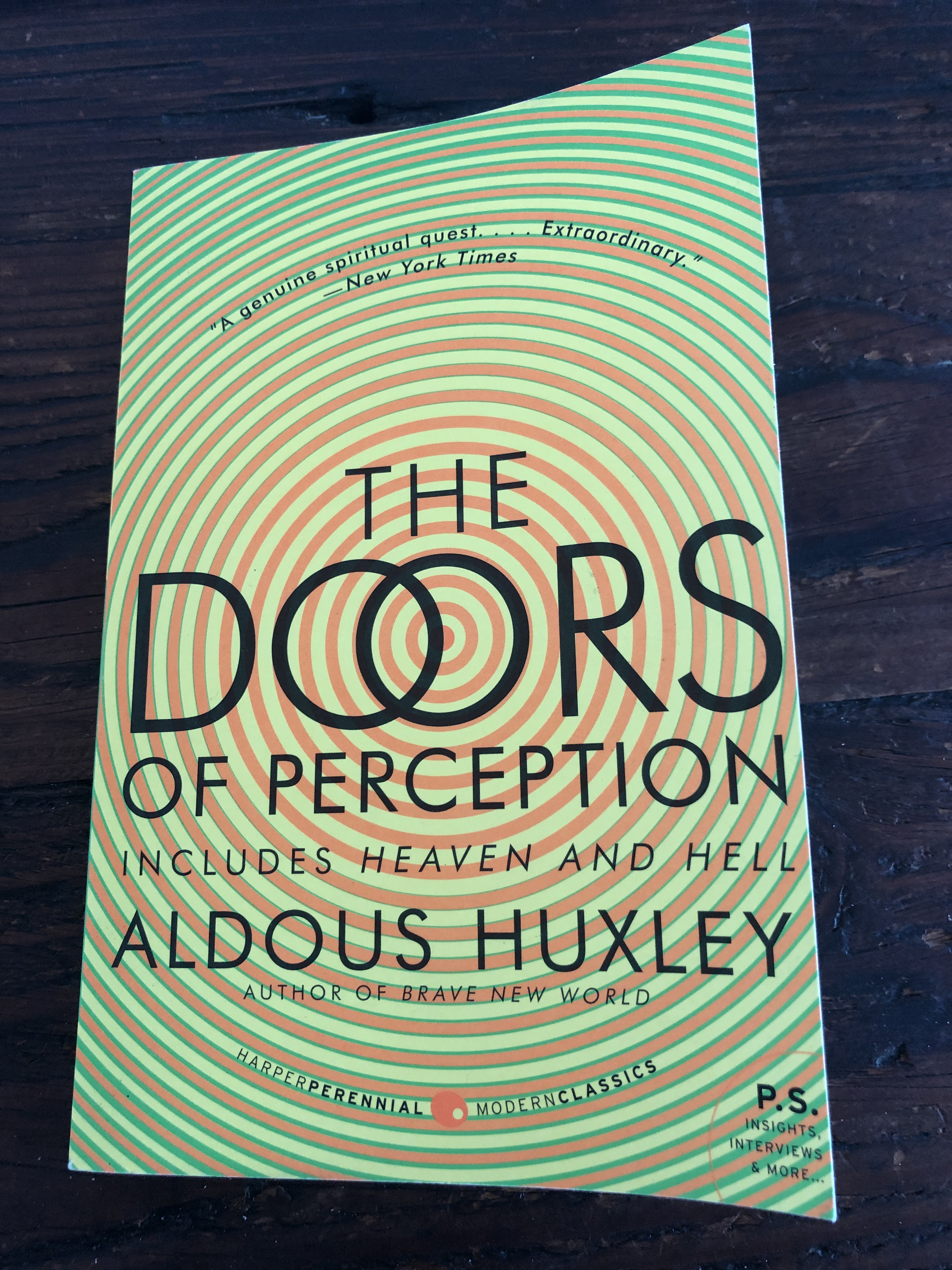

The Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley

Posted: July 19, 2022 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history, drugs Leave a comment

It’s 1953, Aldous Huxley’s in California. He’s close to sixty, a literary man who’s also made a good living as a screenwriter. A friend, one of the “sleuths – biochemists, psychiatrists, psychologists” – has got some mescaline, the active ingredient in peyote. He gives four-tenths of a gram to Aldous and we’re off.

What if you could “know, from the inside, what the visionary, the medium, even the mystic were talking about?” That’s what he’s after.

The mescaline kicks in. Aldous looks at flowers, and the furniture. He looks at a book of Van Gogh paintings, and then a book of Botticelli. He ponders, in particular, the folds of drapery in the pictures.

I knew that Botticelli – and not Botticelli alone, but many others too – had looked at draperies with the same transfigured and transfiguring eyes as had been mine that morning. They had seen the Istigkeit, the Allness and Infinity of folded cloth and had done their best to render it in paint and stone.

Cool. He lies down and his friend hands him a color reproduction of a Cezanne self-portrait.

For the consummate painter, with his little pipeline to Mind at Large by-passing the brain valve and ego-filter, was also just as genuinely this whiskered goblin with the unfriendly eye.

Huxley feels an experience of connecting to “a divine essential Not-self.” Vermeer, Chinese landscape painting, the Biblical story of Mary and Martha, all pass through his mind. William Blake comes up, from him Huxley took his title. Huxley listens to Mozart’s C-Minor Piano Concerto but it leaves him feeling cold. He does appreciate some madrigals of Gesauldo. He finds Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite kind of funny. He’s offered a lunch he’s not interested in, he’s taken for a drive where he “sees what Guardi had seen.”

this?

he comes down.

OK, says Huxley, ideally we’d have some kind of better mescaline that doesn’t last this long and doesn’t cause a small percentage of takers to really spin out. But: we’ve got something here. A possible help on the road to salvation. A substance which allows you to perceive the Mind at Large, to feel the connection to the divine superpower, what he calls in the next essay “out there.”

However, once you go through the Door In The Wall (Huxley credits this phrase to H. G. Wells) you’re not gonna come back the same. You’ll come back “wiser but less cocksure, happier by less self-satisfied,” humbler in the face of the “unfathomable Mystery.”

My friend Audrey who works at the bookstore tells me she sells a lot of copies of this book, mostly to young dudes. The edition I have comes with an additional essay, “Heaven and Hell,” which considers visionary experiences both blissful and appalling, and tries to sort out what we can from them. There’s also an appendix:

Two other, less effective aids to visionary experience deserve mention – carbon dioxide and the stroboscopic lamp.

Huxley finds these less promising.

The price of hay

Posted: June 13, 2022 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history, business Leave a comment

A friend of ours who runs a horse barn told me the price of hay is up $5 a bale, from $27 to $32.

(I know what you’re thinking, that’s a lot for hay, but trust me, these horses are getting primo stuff.)

(painting is Rhode Island Shore by Martin Johnson Heade, at LACMA, not on display last I was there).

Ginevra de’ Benci

Posted: January 30, 2022 Filed under: art history Leave a commentShe spent her later life in self imposed exile, trying to recover from illness and an ill fated love affair. She died in 1521 aged 63 or 64, likely from this unknown illness.

Must have a look at that next time in Washington. How did it end up in Washington? Purchased in the 17th century by a prince of Lichtenstein, then bought from Prince Franz Josef II after World War II.

Have been reading about Leonardo, Machiavelli, and Cesar Borgia in The Artist, the Philosopher, and the Warrior, by Paul Strathern, on the recommendation of Chris Blattman. This book is great, really clarifying the lives and circumstances of these characters.

(source).

Culture notes

Posted: October 27, 2021 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history Leave a comment- I didn’t think Dave Chappelle’s most recent special, The Closer, was his best, although there were some funny jokes in it (on JK Rowling: “this woman sold so many books The Bible got nervous”). The tone was off, or something. Dave Chappelle is a contender for GOAT standup comedian, and also man who’s made impressive choices with significant amounts of money on the line. But I like observing that myself; when he reminds me of these things multiple times in his own special, I find it diminishes the value, akin Matthew 6:2 or the kidney donation lady.

I was texting a friend who had not seen it about the special, and he wrote me something like “what is the obsession with trans people? Why doesn’t he just stop?” In a way the special is Chappelle’s answer to this question, with the conclusion “maybe I will just stop.” If you watch the special, you will see Dave himself describe the feeling of being attacked, harassed, and threatened, which is the same feeling his most extreme critics point to as a reason for being careful about material like this.

Language as spell, as magic, words as having power to cause real harm and violence, to even be violence in themselves, is a belief that is growing over my lifetime. Could that have something to do with a blending of what were once more isolated dialects into a great shared language that incorporates more people, with more divergent opinions and backgrounds? The way English was forming around Shakespeare’s time from like Kentish and Pictish and East Anglian and whatever, blended with Norman French and pieces of Gaelic and Latin all the rest? Such an expansion will not be without confusion.

In 2016 I remember going to the source of a news item that was inspiring controversy, a Department of Education memo on Transgender Students. Here is the Notice of Language Assistance that prefaces the letter:

We’re already in a language mess and we’re not even on page one. I’m not used to reading federal Department of Education documents, I assume this is kind of boilerplate, and well-intentioned. Page 1 of the letter is an attempt to clarify terminology:

An important part of the issue is getting the language right, which will not be easy, language being notoriously tricky and fluid. But if language has the violent power we imbue to it, getting it wrong is very dangerous, like miscasting a spell!

- Sun & Sea at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA was great! An immersive exhibit / opera? I visit Lithuanian Wikipedia to learn about the creators, Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Graintė, Lina Lapelytė,

I was pleased with my burger from Burger She Wrote, although I don’t understand the pun. It’s not like the place is Jessica Fletcher themed or anything. Is it a play on how all burgers are murder?

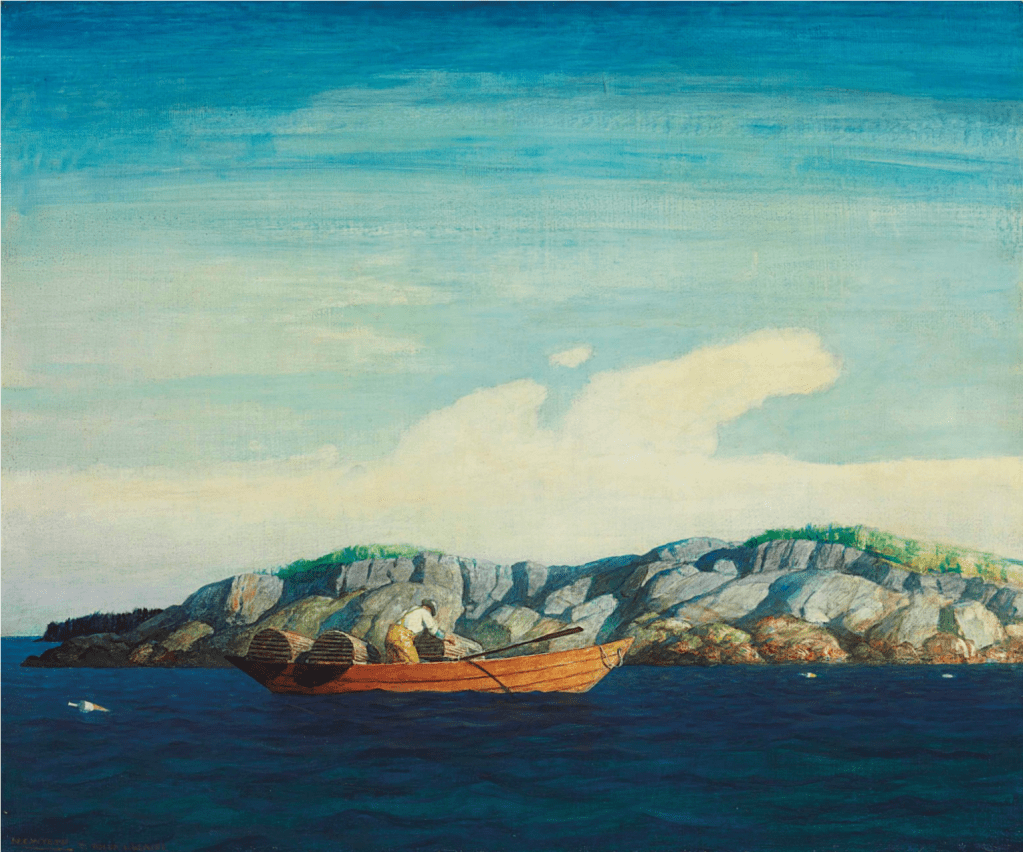

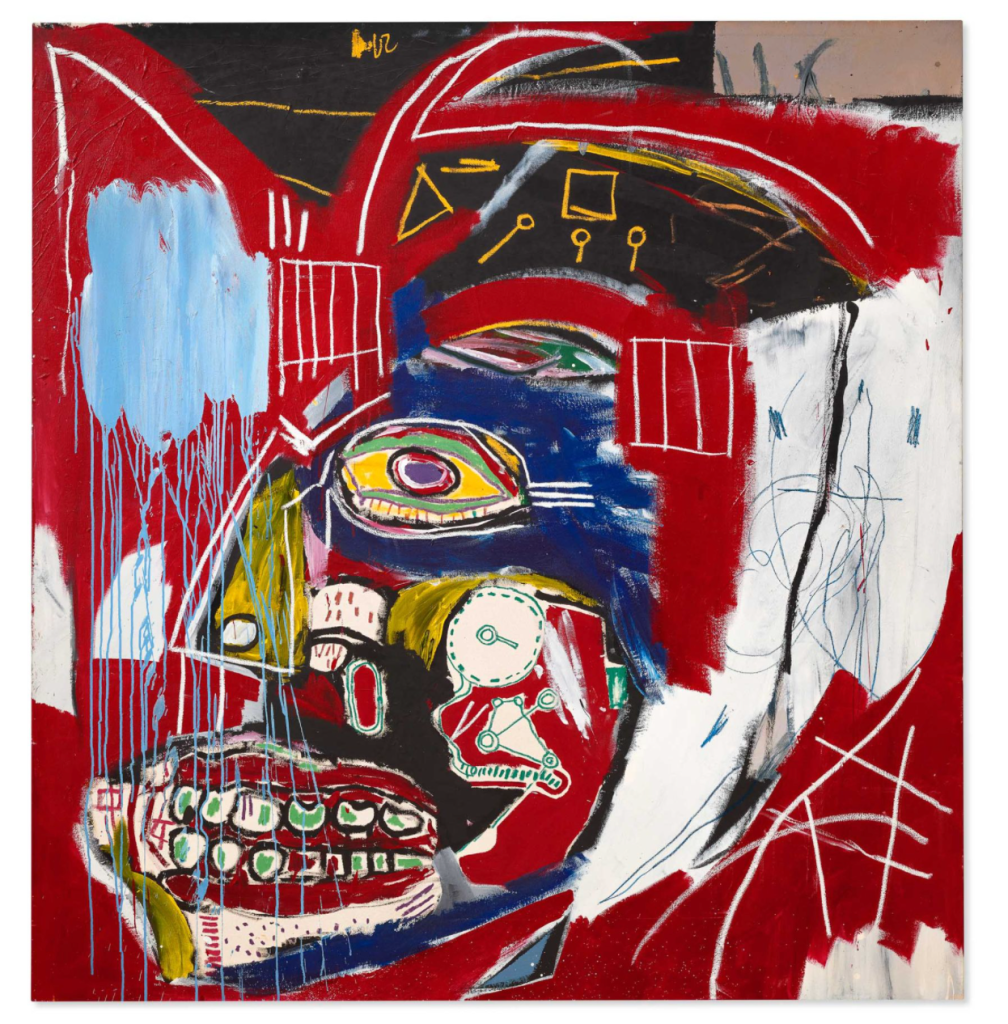

How much would you pay for this painting?

Posted: May 12, 2021 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

NFTs, digital artifacts

Posted: March 23, 2021 Filed under: art history, business 4 CommentsSomebody asked me* if I have any opinion on NFTs, or if I’d be doing an episode of Stocks: Let’s Talk about them. Truth: I do not understand them. I’m trying to gain insight. Why you’d pay lots of money for “ownership” of a digital artwork, or even stranger, pay $2.9 million for “ownership” of Jack Dorsey’s tweets, I don’t get. I’ve read through a lot of message boards and arguments that tend to cycle through the same stuff:

- why would you own something anyone can look at?

- well what about “owning” the Mona Lisa, anyone can look at that but it’s still valuable?

- why would you need to “own” a Picasso, just for bragging rights, this is same as

- what about Walter Benjamin’s “aura”?

- there’s too much money around

- the art market has always had an element of money laundering

- it’s a speculative bubble, it’s like the Dutch tulip craze (contra: we don’t understand the Dutch tulip craze, there was no Dutch tulip craze)

Here’s my one attempt at an original thought, or at least a thought I haven’t seen before: what if people are speculating is that these early NFTs (Beeple’s art, or Jack Dorsey’s tweet) will someday be valuable as digital artifacts, as early works from a new scene, or even a new kind of art?

There’s a scene in the movie Basquiat where Andy Warhol (David Bowie) flips through some postcards offered by Basquiat. I’ve watched that scene and thought, damn, a Basquiat has sold for $110.5 million, if you had just one of those postcards from back then you could at least trade it for enough cash to buy a sweet beach house!

I’ve also pondered in idle moments whether Madonna, who dated Basquiat, has more wealth in the form of Basquiat paintings than she does in her own music catalog. Surely it’s possible she has four or five of her ex-boyfriend’s paintings lying around, which could equal $100 mill easily. (Worse, what if she destroyed them in a fit of grief or jealousy?)

What if people are just betting that the NFT, or the ownership of the image of a tweet, or something, will someday be valuable just as an artifact or sample from this insane time, a time that was pretty interesting in terms of its invention?

The authentication of art has always been an issue, and a challenge. Consider John Berger talking about how much time is spent proving a Leonardo is a Leonardo at the National Gallery:

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has so many Impressionist paintings they don’t know what to do with them all, they’ve got a Van Gogh they keep in storage.

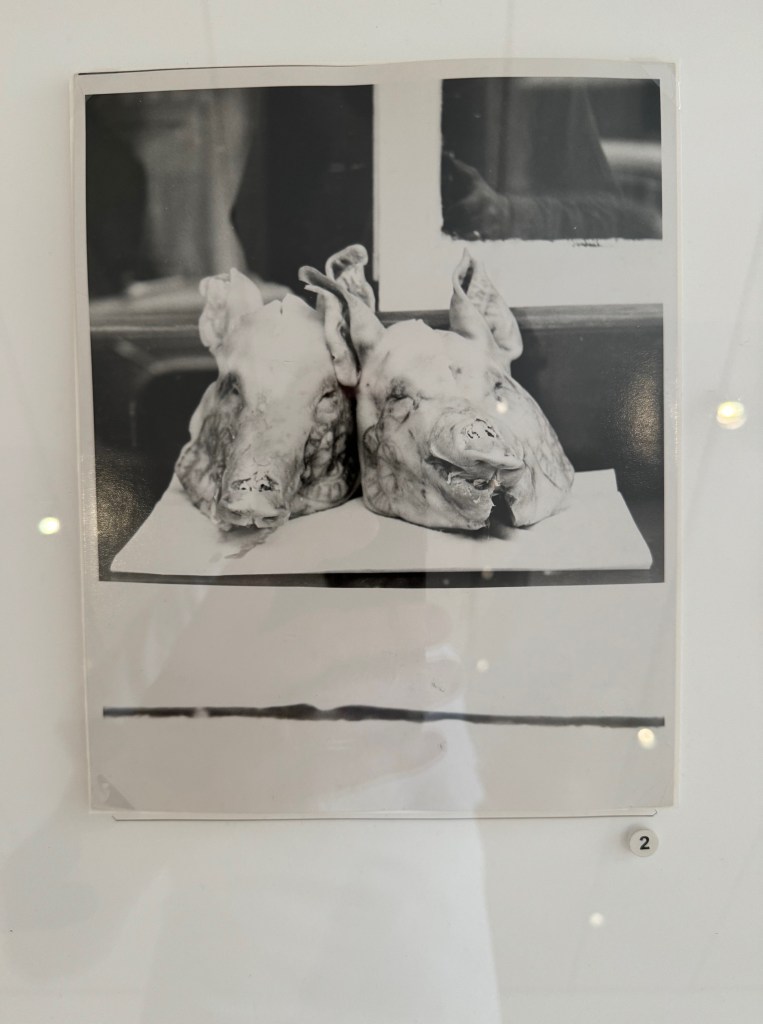

At the time the MFA’s greatest patrons were acquiring art, a Van Gogh wasn’t even that valuable. What was considered valuable art at that time, I once asked a curator there? Stuff like this, she said:

Maybe this is all just marketing spend for crypto/blockchain speculators, as someone suggested somewhere, I can’t remember.

Art speculation is hard! My guess is that NFTs will end up about as valuable as a complete set of 1986 Topps baseball cards, which I once speculatively bought myself as a youth.

Good luck to all the players.

*always funny when someone uses “since people have asked” or “someone asked me” as a setup for writing. In this case I swear I being honest! It was Eben!

The jackrabbit

Posted: December 20, 2020 Filed under: animals, art history, California, the American West, the California Condition Leave a commentWord went out on the community message board that people were finding dead jackrabbits. Healthy looking jackrabbits that appeared to have just dropped dead. There was a plague going around. A jackrabbit plague. RHD2. Rabbit hemorrhagic disease two. The two distinguishes it from original RHD. Bad news, a plague of any kind. Sure enough, a few days later, I saw on the remote camera on the back porch of my cabin out in the Mojave a bird picking at what looked like the muscles and bones of what used to be a jackrabbit.

I drove out there, and found that yes indeed, this had been a jackrabbit. Whether it had died of plague, I don’t know, it seemed possible. I bagged it for disposal, and poured some disinfectant on the ground, as recommended by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The next day, I found another dead jackrabbit. This jackrabbit did not appear to have been hurt in any way. Her eye was open to me. This jackrabbit appeared to have gone into the shade and died. There was no visible trauma and no blood. I didn’t want to get too close, but this was the best chance to examine a jackrabbit, up close and at rest, that I’d ever had. Usually the jackrabbits are fast and on the move. Once they sense you seeing them, they take off.

I won’t put a picture of it here, in case a picture of a dead jackrabbit would upset you. In a way the lack of damage and the animal’s beauty made it much more sad and eerie. It reminded me of Dürer’s drawing of a young hare. I read the Wikipedia page about Dürer’s drawing, which departs from the usual impartial tone to quote praise for the drawing’s mastery:

it is acknowledged as a masterpiece of observational art alongside his Great Piece of Turf from the following year. The subject is rendered with almost photographic accuracy, and although the piece is normally given the title Young Hare, the portrait is sufficiently detailed for the hare to be identified as a mature specimen — the German title translates as “Field Hare” and the work is often referred to in English as the Hare or Wild Hare.

Dürer’s drawing of a walrus is less acclaimed:

The drawing is generally considered as not successful; and is viewed as curious attempted depiction that is neither aesthetically pleasing nor anatomically true to life. Art historians assume the artist drew it from memory having viewed a dead example during a 1520 visit to Zeeland to see a stranded whale which had decomposed before his arrival. Referring to the depiction departure for nature, Durer’s animal has been described as “amusing…it looks more like a hairless puppy with tusks. When Dürer drew from life his accuracy was unquestionable, but he had only briefly seen a walrus, and had only fleeting memory and an elaborate verbal description from which to reconstruct the image”.

The jackrabbit is very similar to the European hare. The suggestion of the magical power of hares is a common theme in Celtic literature and the literature and folklore of the British Isles. We all remember the March Hare.

Most Americans are confused as to just what hares are, chiefly because we are accustomed to calling some of them jackrabbits. Biologically, the chief differences between hares and rabbits are that hares are born with hair and open eyes and can hop about immediately, while rabbits are naked, blind and helpless as birth.

I learned from this book:

which contains recipes for hares, including jugged hare, hasenpfeffer, and hare civit.

Of all the game animals you can hunt in California: elk, wild big, bear, turkey, bighorn sheep, deer, duck, chukar, dove, quail, the jackrabbit alone can be hunted all year round*. There is no season, and there’s no limit. On one of my first trips to California, I was taken out to the desert with the Gamez boys on a jackrabbit hunt. We only saw a few jackrabbits. Nobody got off a good shot at one. I doubt we really wanted to kill one, we just wanted to drive around the desert, shoot guns, and have fun, which we did very successfully.

During the pandemic I got my California hunting license, you could do it entirely online due to Covid restrictions. But I don’t intend to hunt jackrabbits, I don’t want to be like Elmer Fudd.

The meat is said to be quite dry, tough, and gamey. Most recipes call for long simmerings.

If you ever find out in the desert where you must hunt a jackrabbit for food, here’s the Arizona Game and Fish Department telling you how to butcher one.

* non-game animals, like weasels, you can go nuts

Cheyenne Chiefs Receiving Their Young Men

Posted: September 28, 2020 Filed under: art history, Indians Leave a comment

Artist unknown, 1881, from the Bethel Moore Custer Ledger, one of many amazing works over at Plains Indian Ledger Art.

Bethel Moore Custer was, apparently, not related to the “other” Custer.

Scrapbasket

Posted: July 19, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history Leave a comment

Some local street art (by Bandit?). Since painted over I believe. At least I can’t find it.

Photo I took in William Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak, Oxford, MS.

from this WSJ commentary by Kate Bachelder Odell about leadership failures in the US Navy.

“Soldiers bathing, North Anna River, Va.–ruins of railroad bridge in background,” by Timothy O’Sullivan. May 1864. The work of Timothy O’Sullivan has my attention. Follow his photos on the Library of Congress and you’ll travel in time.

by Alexander Hope.

Original Caption: Subway train on the Brooklyn Bridge in Manhattan, New York. The problem of how to move people and goods is ultimately bound up with the quality of life everywhere. The lands adjacent to the Bight, rivers flowing into it, and bays and estuaries edging it have direct upon the environment of the coastal water. The New York, New Jersey metropolitan region is one of the most congested in the world, 05/1974.

Just thought this was funny.

George P.A. Healy (G.P.A. Healy)

Posted: June 10, 2020 Filed under: America, America Since 1945, art history Leave a comment

Healy was born in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the eldest of five children of an Irish captain in the merchant marine. Having been left fatherless at a young age, Healy helped to support his mother. At sixteen years of age he began drawing, and at developed an ambition to be an artist. Jane Stuart, daughter of Gilbert Stuart, aided him, loaning him a Guido’s “Ecce Homo”, which he copied in color and sold to a country priest. Later, she introduced him to Thomas Sully, by whose advice Healy profited, and gratefully repaid Sully in the days of the latter’s adversity.

so far as I know no relation, there are plenty of Healys and Helys from here to Australia.

He painted Tyler

and drew Grant.

He’s got a few that have appeared in the White House, like this one, The Peacemakers.

Yolo -> Yo lo vi

Posted: June 2, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history Leave a comment

Interested in the Goya drawing, in his series Los Desastres de la Guerra, where his only commentary is “yo lo vi.” I saw it. What else is there to say sometimes?

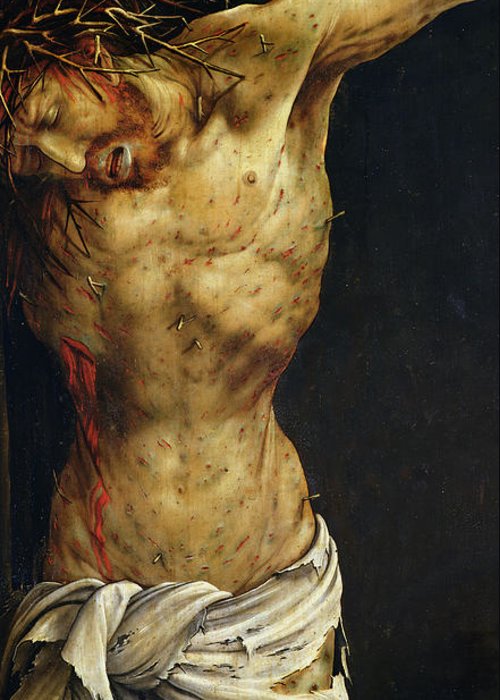

Good Friday

Posted: April 10, 2020 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

For the first three centuries after his death, this Renaissance artist [Matthias Grünewald] did not attract much attention. But around 1900 the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans made a passionate plea for the relevance and modernity of Grünewald. In his description of the altar at Isenheim, Huysmans called attention to Grünewald’s shocking insistence on the physical details of Christ’s suffering, alerting its beholder to the disgusting marks of torture and the signs of dying and decomposing flesh (figs. 1a and 1b). Such a Christ, Huysmans observed, is no longer the well-groomed, handsome man who has been venerated by the rich and powerful throughout the ages. Grünewald’s Christ is rather the “God of the Poor. The one who chose the company of those in misery and of those who had been rejected, of all those for whose ugliness and need the world could only feel contempt.”3 And it was exactly this approach to pain and suffering highlighted by Huysmans that subsequently became a point of reference for many artists who invoked Grünewald’s work, especially when they cited the triptych from the Isenheim altarpiece or The Mockery of Christ (fig. 2)from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich

source for all that.

Not the Van Gogh painting I would’ve stolen

Posted: March 30, 2020 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

A bit dreary? But you take what you can get I guess!