Restaurants and Railroads: hospice brands

Posted: February 14, 2026 Filed under: business, railroads and restaurants Leave a comment

Sad. From ValueLine.

Bamberger

Posted: February 6, 2026 Filed under: business Leave a commentfrom a WSJ obituary of J. David Bamberger, conservationist and shareholder in Church’s Chicken.

He learned, for example, to place new locations in middle-class neighborhoods, but right on the border of lower-income ones; the real estate was cheaper, and you doubled your clientele. “Black people would come over to the white neighborhood to buy chicken. But if you put a store in a predominantly black neighborhood, white people wouldn’t come over and buy there,” Bamberger lamented in LeBlanc’s book.

There’s a Church’s Chicken in the Inland Empire on the way back from Joshua Tree, it’s not quality. But Bamberger retired in 1988. More:

In addition to his restoration of the land now known as “Selah, Bamberger Ranch Preserve,” Bamberger was instrumental in the preservation of nearby Bracken Cave in the early 1990s, home to more than 15 million Mexican free-tailed bats—a colony believed to be the largest concentration of nonhuman mammals on the planet. Bamberger gained the trust of the family that owned the cave and brokered a sale to the nonprofit Bat Conservation International, then paid to build a trail system and other infrastructure to make the site accessible to visitors.

Suddenly enchanted by bats, Bamberger next hired biologists and geologists to hunt for a spot at Selah where he could establish a bat population of his own. They couldn’t find a single suitable site.

“Most people would have said, ‘Oh well, that’s too bad. I guess we’re not going to have a big bat colony here,’ ” explained April Sansom, executive director of Selah, Bamberger Ranch Preserve. “But not J. David. What he said was, ‘Oh, guess we better try to build one.’ ”

Construction of a system of underground caves was completed in 1997—a mammoth project which Bamberger conceded was “eccentric” even for him, and which was mocked locally as “Bamberger’s Folly.” It took several years, and some iterative modifications to the structure, but wild bats eventually moved in and established a colony there. The population is now half-a-million strong.

You can beat a race, but you can’t beat the races

Posted: April 18, 2025 Filed under: business Leave a comment

Alex Morris has published a compilation of Buffett and Munger remarks at annual meetings. This allowed me to add to my file of times the two have talked about horse race betting and the lessons to be learned there.

Munger’s quote, in his Worldly Wisdom speech, is the bluntest of all:

How do you get to be one of those who is a winner—in a relative sense—instead of a loser? Here again, look at the pari-mutuel system. I had dinner last night by absolute accident with the president of Santa Anita. He says that there are two or three betters who have a credit arrangement with them, now that they have off-track betting, who are actually beating the house. They’re sending money out net after the full handle—a lot of it to Las Vegas, by the way—to people who are actually winning slightly, net, after paying the full handle. They’re that shrewd about something with as much unpredictability as horse racing. And the one thing that all those winning betters in the whole history of people who’ve beaten the pari-mutuel system have is quite simple. They bet very seldom. It’s not given to human beings to have such talent that they can just know everything about everything all the time. But it is given to human beings who work hard at it—who look and sift the world for a mispriced bet—that they can occasionally find one. And the wise ones bet heavily when the world offers them that opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they don’t. It’s just that simple. That is a very simple concept. And to me it’s obviously right—based on experience not only from the pari-mutuel system, but everywhere else.”

I noted professional horseplayer Inside The Pylons saying something related on his Bet With The Best podcast appearance:

Like you have no chance doing stuff like that long term. So you only bet the races where you think are good betting races.

But when you look at nine to nine or 10 races, Santa Anita, I mean, jeez, even if you’re sharp, I mean, if you bet more than three races a day, you’re a sicko I mean, there’s just so many bad races.

This theme recurs in the Morris compilation:

2003 MEETING (02:36:36) *

WB: “The beauty of the investment game, what really makes it great, is that you don’t have to be right on everything. You don’t have to be right on 20%, 10%, or even 5% of the companies in the world. You only have to get one good idea every year or two. I used to be very interested in horse handicapping, and the old story was you could beat a race but you can’t beat the races … If somebody gave me all five hundred stocks in the S&P and I had to make some prediction about how they would behave relative to the market over the next couple years, I don’t know how I would do. But maybe I could find one where I’m 90% sure I’m right. It’s an enormous advantage in stocks: You only have to be right on a very, very few things as long as you never make big mistakes.”

ACTIVE MANAGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS

1997 MEETING (01:21:40)

WB: “Money managers, in aggregate, have underperformed index funds. It’s the nature of the game. They simply cannot overperform, in aggregate. There are too many of them managing too big a portion of the pool. It’s for the same reason that the crowd could not come out here to Ak-Sar-Ben [racetrack] and make money, in aggregate, because there’s a bite taken out of every dollar that was invested in the pari-mutuel machines. People who invest their dollars elsewhere through money managers in aggregate cannot do as well as they could do by themselves in an index fund. They say you can’t get something for nothing. But the truth is money managers, in aggregate, have gotten something for nothing; they’ve gotten a lot for nothing. And the corollary is investors have paid something for nothing. That doesn’t mean people are evil.

FROM POOR INVESTMENTS

1995 MEETING (01:01:17)

WB: “A very important principle in investing is that you don’t have to make it back the way you lost it. In fact, it’s usually a mistake to try and make it back the way that you lost it.”

CM: “That’s the reason so many people are ruined by gambling; they get behind and then they feel they have to get it back the way they lost it. It’s a deep part of human nature. It’s very smart just to lick it by will; little phrases like that are very useful.”

WB: “One of the important things in stocks is that the stock does not know you own it. You have all these feelings about it; you remember what you paid and you remember who told you about it, all these little things. And it doesn’t give a damn, it just sits there. If a stock is at $50 when somebody’s paid $100, they feel terrible. Meanwhile, somebody else who paid $10 feels wonderful. It has no impact whatsoever. As Charlie says, gambling is the classic example. Someone goes out and gets into a mathematically disadvantageous game. They start losing it, and they think they’ve got to make it back, not only the way they lost it, but that night. It’s a great mistake.”

Some other words of interest: On ValueLine:

PATIENCE (WATCHING FOR HISTORIC FINANCIAL DATA)

1995 MEETING (03:54:41)

CM: “I think the one set of numbers that are the best quick guide to measuring one business against another are the Value Line numbers. That stuff on the log scale paper going back fifteen years, that is the best one-shot description of a lot of big businesses that exists. I can’t imagine anybody being in the investment business involving common stocks without that on their shelf.”

WB: “And, if you have in your head how all of that looks in different businesses and industries, then you’ve got a backdrop against which to measure. If you’d never watched a baseball game and never seen a statistic on it, you wouldn’t know whether a .3o0 hitter was a good hitter or not. You have to have some kind of a mosaic there that you’re thinking is implanted against, in effect. And the Value Line figures, if you ripple through that, you’ll have a pretty good idea of what’s happened over time in American business.”

CM: “I would like to have that material going all the way back; they cut it off at fifteen years back. I wish I had that in the office, but I don’t.”

WB: “I saved the old ones. We tend to go back. If I’m buying Coca-Cola, I’ll go back and read the Fortune articles from the 193os on it. I like a lot of historical background on things, just to get it in my head how the business has evolved over time, and what’s been permanent and what hasn’t been permanent, and all of that. I probably do that more for fun than for actual decision-making. We’re trying to buy businesses we want to own forever, and if you’re thinking that way you might as well look back a way and see what it’s been like to own them forever.”

The way you learn about businesses is by absorbing information about them, thinking, deciding what counts and what doesn’t count, relating one thing to another. That’s the job. And you can’t get that by looking at a bunch of little numbers on a chart bobbing up and down or reading market commentary and periodicals or anything of the sort. That just won’t do it. You’ve got to understand the businesses. That’s where it begins and ends.”

SCUTTLEBUTT (ON-THE-GROUND RESEARCH)

1998 MEETING (04:27:09)

WB: “One advantage of allocating capital is that an awful lot of what you do is cumulative in nature, so you get continuing benefits out of things you’ve done earlier. By now, I’m fairly familiar with most of the businesses that might qualify for investment at Berkshire. But when I started out, and for a long time, I used to do a lot of what Phil Fisher described, the scuttlebutt method …

“The general premise of why you’re interested in something should be 80% of it.

You don’t want to be chasing down every idea that way; you should have a strong presumption. You should be like a basketball coach who runs into a seven-footer on the street. You’re interested to start with; now you have to find out if you can keep him in school, if he’s coordinated, and all that sort of thing. That’s the scuttlebutt aspect of it. But as you’re acquiring knowledge about industries in general, and companies specifically, there really isn’t anything like first doing some reading about them, and then getting out and talking to competitors, customers, suppliers, ex-employees, current employees, whatever it may be. You will learn a lot. But it should be the last 10% or 20%. You don’t want to get too impressed by that, because you really want to start with a business where you think the economics are good, where they look like seven-footers, and then you want to go out with a scuttlebutt approach to possibly reject your original hypothesis. Or maybe, if you confirm it, do it even more strongly.

“I did that with American Express back in the 1g6os; essentially the scuttlebutt approach so reinforced my feeling about it that I kept buying more and more as I went along. If you talk to a bunch of people in an industry and you ask them

STOCK SELECTION

1998 MEETING (03:02:34)

WB: “The criteria for selecting a stock is really the criteria for looking at a business. We are looking for a business we can understand. They sell a product that we think we understand, or we understand the nature of the competition and what could go wrong with it over time. And then we try to figure out whether the economics, the earnings power, over the next five, ten, or fifteen years is likely to be good and getting better, or poor and getting worse. Then we try to decide whether we’re getting in with people that we feel comfortable being in with. And then we try to decide what’s an appropriate price for what we’ve seen up to that point in the business.

“What we do is simple, but it is not necessarily easy. The checklist that we go through in our minds is not very complicated. Knowing what you don’t know is important; knowing the future is impossible in many cases, and difficult in others. We’re looking for the ones that are relatively easy. Then you have to find it at a price that’s interesting to you, and that’s very difficult for us now (although there have been periods in the past where it’s been a total cinch).

“That’s what goes through our mind. If you were thinking of buying a gas station, dry cleaner, or convenience store to invest your life savings in and to run as a business, you’d think about the competitive position and what it would look like five to ten years from now, and how you were going to run it, or who was going

“Buy when there’s blood in the streets”

Posted: April 6, 2025 Filed under: advice, business 3 Comments

On the famous quote sometimes attributed to Nathan Rothschild

His four brothers helped co-ordinate activities across the continent, and the family developed a network of agents, shippers and couriers to transport gold—and information—across Europe. This private intelligence service enabled Nathan to receive in London the news of Wellington’s victory at the Battle of Waterloo a full day ahead of the government’s official messengers.[2] He is famously quoted as saying “Buy when there’s blood in the streets”, though the original quote is believed to have appended “even if the blood is your own”. The quote refers to his contrarian investing strategy that he is well known for adhering to as to buy assets when the financial markets are crashing and panicking investors are selling. The quote has a tremendous impact today on value investing and modern businesspeople and investors alike when buying assets in down markets when investment opportunities arise.[3][4][5]

The first part of this concerning the Battle of Waterloo has already been adequately dealt with. The second part of this seems equally dubious, and I can’t find a good source for it. You can find this “buy when there is blood in the streets” quote in many modern business books, but they hardly count as a reliable source for a biography of Nathan Rothschild. The earliest sources I’ve found so far date from 1907/8 – for example Thomas Gibson’s Market Letters for 1907 contains the following supposed conversation:

“Buy Rentes,” advised Rothschild.

“But the streets of Paris are running with blood.”

“That is why you can buy Rentes so cheap.”

Grateful to Wikipedia editor Franz for getting to the bottom of that quote.

The first time I heard Cass McCombs was in a car in Queensland, Australia. The aux cord wasn’t working properly, so the vocals weren’t coming through, just the instrumentals. For awhile I was like “who is this genius that just plays rhythmic patterns?!” It was cool either way!

People drop this quote every time there’s a stock market downturn. But it sounds like Rothschild was speaking of a time when blood was literally running in the streets.

Snappy lines from Uncle Warren

Posted: February 24, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business Leave a commentWarren Buffett at 94 still writing in a crisp, appealing style in his annual letter. Is he fibbing a bit when he brags about not doing due diligence on real estate purchases? And bragging on himself for how much tax he pays, when he surely uses every dodge he can? Maybe so. He’s a mythmaker.

A decent batting average in personnel decisions is all that can be hoped for. The cardinal sin is delaying the correction of mistakes or what Charlie Munger called “thumb-sucking.” Problems, he would tell me, cannot be wished away. They require action, however uncomfortable that may be.

The philosophy:

… we own a small percentage of a dozen or so very large and highly profitable businesses with household names such as Apple, American Express, Coca-Cola and Moody’s. Many of these companies earn very high returns on the net tangible equity required for their operations. At yearend, our partial-ownership holdings were valued at $272 billion. Understandably, really outstanding businesses are very seldom offered in their entirety, but small fractions of these gems can be purchases Monday through Friday on Wall Street, and very occasionally, they sell at bargain prices.

Inflation:

Paper money can see its value evaporate if fiscal folly prevails. In some countries, this reckless practice has become habitual, and, in our country’s short history, the U.S. has come close to the edge. Fixed-coupon bonds provide no protection against runaway currency.

Businesses, as well as individuals with desired talents, however, will usually find a way to cope with monetary instability as long as their goods or services are desired by the country’s citizenry. So, too, with personal skills. Lacking such assets as athletic excellence, a wonderful voice, medical or legal skills or, for that matter, any special talents, I have had to rely on equities throughout my life. In effect, I have depended on the success of American businesses and I will continue to do so.

One way or another, the sensible – better yet imaginative – deployment of savings by citizens is required to propel an ever-growing societal output of desired goods and services. This system is called capitalism. It has its faults and abuses – in certain respects more egregious now than ever – but it also can work wonders unmatched by other economic systems.

The insurance biz:

When writing P/C insurance, we receive payment upfront and much later learn what our product has cost us – sometimes a moment of truth that is delayed as much as 30 or more years.

(We are still making substantial payments on asbestos exposures that occurred 50 or more years ago.)

This mode of operations has the desirable effect of giving P/C insurers cash before

they incur most expenses but carries with it the risk that the company can be losing money – sometimes mountains of money – before the CEO and directors realize what is happening.

After some years of reading Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger materials these letters become kind of familiar, but it’s soothing, like hearing a folktale told once again with a few variations.

Power by Jeffrey Pfeffer (2010)

Posted: February 22, 2025 Filed under: advice, America Since 1945, business Leave a comment

Pulled this one from my shelf because I remembered there was a funny claim about how flattery 100% of the time no exceptions always works. Indeed:

Most people underestimate the effectiveness of flattery and therefore underutilize it. If someone flatters you, you essentially have two ways of reacting. You can think that the person was insincere and trying to butter you up. But believing that causes you to feel negatively about the person whom you perceive as insincere and not even particularly subtle about it. More importantly, thinking that the compliment is just a strategic way of building influence with you also leads to negative self-feelings— what must others think of you to try such a transparent and false method of influence? Alternatively, you can think that the compliments are sincere and that the flatterer is a wonderful judge of people— a perspective that leaves you feeling good about the person for his or her interpersonal perception skill and great about yourself, as the recipient of such a positive judgment delivered by such a credible source. There is simply no question that the desire to believe that flattery is at once sincere and accurate will, in most instances, leave us susceptible to being flattered and, as a consequence, under the influence of the flatterer.

So, don’t underestimate—or underutilize-the strategy of flattery.

University of California-Berkeley professor Jennifer Chatman, in an unpublished study, sought to see if there was some point beyond which flattery became ineffective. She believed that the effectiveness of flattery might have an inverted U-shaped relationship, with flat tery being increasingly effective up to some point but beyond that becoming ineffective as the flatterer became seen as insincere and a “suck up.” As she told me, there might be a point at which flattery became ineffective, but she couldn’t find it in her data.

Amazing. A powerful move:

I have observed similar ploys used to gain power in business meetings. In most companies, the strategy and market dynamics are taken for granted. If someone challenges these assumptions-such as how the company is competing, how it is measuring success, what the strategy is, who the real competitors are now and in the future— this can be a very potent power play. The questions and challenges focus attention on the person bringing the seemingly commonsense…

How to get powerful? There’s a simple plan:

The fundamental principles for building the sort of reputation that will get you a high-power position are straightforward: make a good impression early, carefully delineate the elements of the image you want to create, use the media to help build your visibility and burnish your image, have others sing your praises so you can surmount the self-promotion dilemma, and strategically put out enough negative but not fatally damaging information about yourself that the people who hire and support you fully understand any weaknesses and make the choice anyway. The key to your success is in executing each of these steps well.

A tale of California politics:

In government, Jesse Unruh, a former Democratic political boss and treasurer of Califor-nia, called money the mother’s milk of politics. Former two-term San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, whose 16 years as speaker and virtual ruler of the California Assembly prior to becoming mayor marked him as an extremely effective politician, began his campaign for the legislative leadership post by raising a lot of money. And since he was from a “safe” district, he gave that money to his legislative colleagues to help them win their political contests. Brown understood an important principle: having resources is an important source of power only if you use those resources strategically to help others whose support you need, in the process gaining their favor. In contrast to Brown, the Assembly speaker at the time, Leo McCarthy, irritated his Democratic colleagues to the point of revolt by holding a $500,000 fundraiser in Los Angeles featuring Ted Kennedy and then using 100 percent of the money for his nascent efforts to run for statewide office.’ He was soon out of his job, replaced by Willie Brown.

(Similar schemes are a theme in Caro’s LBJ book, he got lots of money from powerful Texas guys to whom he steered government contracts for projects like dams, then he distributed that money around Congress to his desperate colleagues).

If you want power don’t give up power:

You need to be in a job that fits and doesn’t come with undue political risks, but you also need to do the right things in that job. Most important, you need to claim power and not do things that give yours away. It’s amazing to me that people, in ways little and big, voluntarily give up their power, preemptively surrendering in the competition for status and influence. The process often begins with how you feel about yourself. If you feel powerful, you will act and project power and others will respond accordingly. If you feel power-less, your behavior will be similarly self-confirming.

Restaurants and Railroads: Chili’s Triple Dip Boom

Posted: February 20, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, beverages, business, food 1 Comment

Once I’m cast off from show business perhaps I’ll start a newsletter called Restaurants and Railroads. This will analyze those two types of businesses, specifically publicly traded companies. Hedge funds as well as passionate hobbyists will subscribe. They’ll invite me to their conferences, to which I’ll travel in style, by rail when possible. I’ll sample the various restaurants as I go, Tijuana Flats for example, and Pizza Inn which I’ve never tried. In a world of niche media I wonder if I could make that work.

You might not think restaurants and railroads are a natural combination. Fred Harvey might disagree, but I’ll concede they’re very different businesses. The railroads have no new competition, no one is building a new railroad. Only a handful of companies control all the track. Two railroads serve the port of LA: one is BSNF, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, and one is Union Pacific. A duopoly.

The restaurants on the other hand are in frantic, constant competition. They must capture taste and vibe. Tastes change, vibes shift. Plus your customer could always just make a sandwich. How restaurants stay profitable? How do they maintain quality, especially at scale?

These two differing business categories are the two I’m excited to read about when I get an issue of ValueLine. Consumer Staples, Metals & Mining, etc, these lose our interest. But take a look at a personality like Kent Taylor’s or a real railroader like Hunter Harrison (or Casey Jones) and the mind comes to life, it’s hard to get bored.

In the publicly traded restaurant space, a big story this year has been Chili’s:

Chili’s may have just pulled off one of the greatest comebacks in restaurant history.

Same-store sales at the bar and grill chain surged more than 31% from October to December, marking its best quarter since the period just after COVID and accelerating a streak of double-digit same-store sales increases that began last April.

The growth once again was driven by a mix of social media buzz, value-based advertising and a renewed focus on restaurant operations and atmosphere that seemed to snowball as the year progressed.

Just to put this into context, these numbers are comparable to when Popeye’s went off with their spicy chicken sandwich. CEO Kevin Hochman points to TikTok:

About halfway through last year, its Triple Dipper appetizer platter, a staple on the chain’s menu for years, went viral on TikTok, where young customers showed off their “cheese pulls” with the Triple Dipper’s fried mozzarella sticks. …

“What’s happening is that young people are coming in after they’ve seen us on TikTok, and they’re like, ‘Wow, this experience is really good,’ and it becomes a part of the rotation,” Hochman told analysts during an earnings call Wednesday. “I think that’s why you’ve seen the longevity in the results and the acceleration, not just kind of a boom-splat that you typically would see without the operational investments that we’ve made in the business.”

Kevin Hochman seems like a brand guy: while at P&G he worked on Old Spice. $EAT stock has indeed thrived:

On an episode of A Deeper Dive, a quick service restaurant business podcast, the host and guest discussed Chili’s phenomenal success, and possible reasons for it. The fast food competitive price with the sit down experience came up, as did the mix and match. But in the end they agreed people just kinda like it.

It does seem like Chili’s is doing something right:

reviewing some news in The Wall Street Journal

Posted: February 3, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, food 3 CommentsI don’t care for Applebee’s, it’s sub Friday’s and way sub Chili’s, but I do like living in the United States of America. All told this was a nice story. The conclusion:

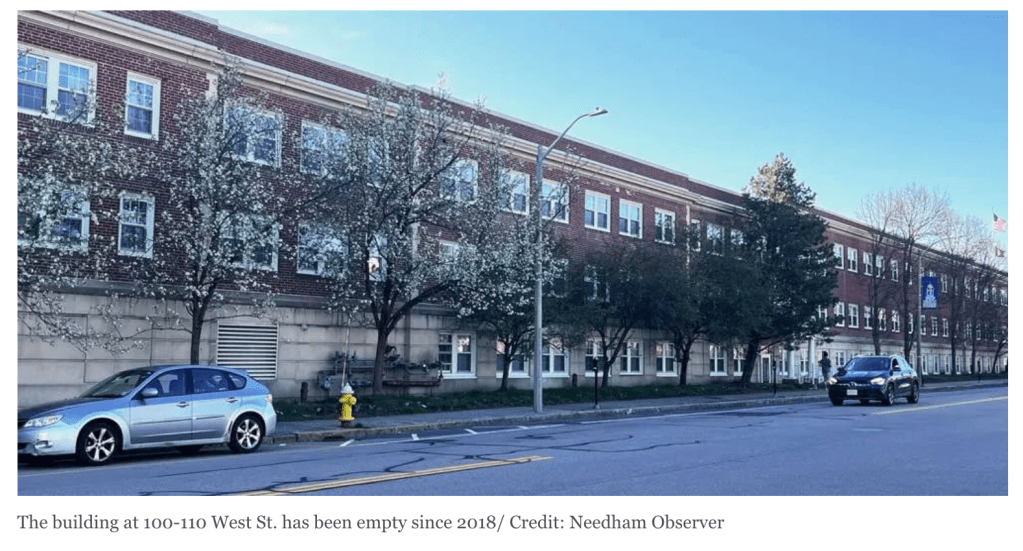

Carter’s, congealed electricity, AI and Needham

Posted: January 30, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, children, New England, Uncategorized Leave a comment

If you have a little kid in the US you will have some clothes from Carter’s. They sell them at Target and Wal-Mart as well as 1,000 or so Carter’s stores, and they cost $8.

Before I had a kid it didn’t occur to me that kids outgrow their clothes so fast they can’t cost too much.

When I see the Carter’s label, I think of my home town.

William Carter founded Carter’s in Needham, Massachusetts in 1865. Textiles were a big business in New England. Two inputs, labor and electricity, were cheap. Labor from excess farm children, and electricity from running streams? That would’ve been the earliest mode, what were they using by 1865? Coal?

One of the biggest buildings in Needham, certainly the longest, is the former Carter’s headquarters, which stretches itself along Highland Avenue. A prominent landmark, it took a long time to walk past.

The story of Carter’s is a global economic story in miniature.

Old Carter mill #2, found here.

The Carter family sold the company in the 1990s. It went public in 2003. In 2005, Carter’s acquired OshKosh B’gosh, a company famous for making children’s overalls. This company started in 1895 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin (the name comes from an Ojibwe word, “The Claw,” that was the name of a local chief).

The term “B’gosh” began being used in 1911, after general manager William Pollock heard the tagline “Oshkosh B’Gosh” in a vaudeville routine in New York.[4] The company formally adopted the name OshKosh B’gosh in 1937.

OshKosh B’Gosh’s Wisconsin plant was closed in 1997. Downsizing of domestic operations and massive outsourcing and manufacturing at Mexican and Honduran subsidiaries saw the domestic manufacturing share drop below 10 percent by the year 2000.

OshKosh B’Gosh was sold to Carter’s, another clothing manufacturer for $312 million

The headquarters of Carter’s moved to Atlanta. Labor and electricity were cheaper in Georgia, Carter’s had been opening mills in the South for awhile. Now the clothes are made overseas. I look at the labels on Carter’s clothes: Bangladesh, India, Cambodia, Vietnam. If you factor in the shipping and the markup how much of that $8 is going to your garment maker in Bangladesh? Then again maybe it’s the best job around, raising Bangladeshis out of poverty, and soon Chittagong will look like Needham.

The former Carter’s headquarters, now vacant, became a facility for elder living. My mom worked there, briefly. Carter’s today is headquarted in the Phipps Tower in Buckhead, Atlanta, which I happened to pass by the other day.

The loss of the mill and the company headquarters was not a crisis for Needham. Needham is very close to Boston, an easy train ride away, and along of the 128 Corridor. There are growth businesses in the area, hospitals, biotech companies, universities. TripAdvisor is based in Needham. Needham is a pleasant town, there are ongoing talks to turn the former Carter’s building into housing. It would be close to public transport and walkable to the library and the Trader Joe’s. That seems to be stalled.

Needham has brain jobs, attached to a dense brain network, while brawn jobs are being shipped overseas. There are many other towns in Massachusetts where the old run down mill is a sad derelict as production moved first south and then overseas. These towns are bleak. Oshkosh, Wisconsin seems ok, but the shipping of steady jobs overseas is of course a major factor in our politics, Ross Perot was talking about it in 1992 and no one did anything about it and now Trump is the president.

A similar story lies in the history of Berkshire Hathaway – the original New Bedford textile mill, not the conglomerate Warren Buffett built on top of it using the same name. Buffett talks about this, I believe this is from the 2022 annual meeting:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I remember when you had a textile mill —

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, god.

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and it couldn’t —

WARREN BUFFETT: I try to forget it. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and the textiles are really just congealed electricity, the way modern technology works.

And the TVA rates were 60% lower than the rates in New England. It was an absolutely hopeless hand, and you had the sense to fold it.

WARREN BUFFETT: Twenty-five years later, yeah. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, you didn’t pour more money into it.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, that’s right.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And, no — recognizing reality, when it’s really awful, and taking appropriate action, just involves, often, just the most elementary good sense.

How in the hell can you run a textile mill in New England when your competitors are paying way lower power rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: And I’ll tell you another problem with it, too. I mean, the fellow that I put in to run it was a really good guy. I mean, he was 100% honest with me in every way. And he was a decent human being, and he knew textiles.

And if he’d been a jerk, it would have been a lot easier. I would have probably thought differently about it.

But we just stumbled along for a while. And then, you know, we got lucky that Jack Ringwalt decided to sell his insurance company [National Indemnity] and we did this and that.

But I even bought a second textile company in New Hampshire, I mean, I don’t know how many — seven or eight years later.

I’m going to talk some about dumb decisions, maybe after lunch we’ll do it a little.

Congealed electricity, what a phrase. In the 1985 annual letter, Buffett discusses the other input, labor, which was cheaper in the South, and why he kept Berkshire Hathaway running in Massachusetts anyway:

At the time we made our purchase, southern textile plants – largely non-union – were believed to have an important competitive advantage. Most northern textile operations had closed and many people thought we would liquidate our business as well.

We felt, however, that the business would be run much betterby a long-time employee whom. we immediately selected to be president, Ken Chace. In this respect we were 100% correct: Ken

and his recent successor, Garry Morrison, have been excellent managers, every bit the equal of managers at our more profitable businesses.… the domestic textile industry operates in a commodity business, competing in a world market in which substantial excess capacity exists. Much of the trouble we experienced was attributable, both directly and indirectly, to competition from foreign countries whose workers are paid a small fraction of the U.S. minimum wage. But that in no way means that our labor force deserves any blame for our closing. In fact, in comparison with employees of American industry generally, our workers were poorly paid, as has been the case throughout the textile business. In contract negotiations, union leaders and members were sensitive to our disadvantageous cost position and did not push for unrealistic wage increases or unproductive work practices. To the contrary, they tried just as hard as we did to keep us competitive. Even during our liquidation period they performed superbly. (Ironically, we would have been better off financially if our union had behaved unreasonably some years ago; we then would have recognized the impossible future that we faced, promptly closed down, and avoided significant future losses.)

Buffett goes on, if you care to read it, to discuss the dismal spiral faced by another New England textile company, Burlington.

Charlie Munger, in his 1994 USC talk, spoke on the paradoxes here:

For example, when we were in the textile business, which is a terrible commodity business, we were making low-end textiles—which are a real commodity product. And one day, the people came to Warren and said, ‘They’ve invented a new loom that we think will do twice as much work as our old ones.’

And Warren said, ‘Gee, I hope this doesn’t work because if it does, I’m going to close the mill.’ And he meant it.

What was he thinking? He was thinking, ‘It’s a lousy business. We’re earning substandard returns and keeping it open just to be nice to the elderly workers. But we’re not going to put huge amounts of new capital into a lousy business.’

And he knew that the huge productivity increases that would come from a better machine introduced into the production of a commodity product would all go to the benefit of the buyers of the textiles. Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.

That’s such an obvious concept—that there are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Is something similar happening with AI? Who will it make rich, and at what cost? To whose ribs will the profits stick?

I’m not sure we could call AI congealed but it is more or less just more and more electricity run through expensive processors. Who will win from that? So far it’s been the makers of the processors, but if DeepSeek shows you don’t need as many of those the game is changed. Personally I’m unimpressed with DeepSeek – try asking it what happened in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

How does Carter’s itself continue to survive? Target’s own brand, Cat & Jack, is right next door on the shelves. Could another company shove Carter’s aside if they can cut the margins even thinner, get the price down to $7? Here’s what Carter’s CEO Michael Casey has to say in their most recent annual letter:

Hard to build the operational network Carter’s has over 150+ years. There will be a challenge awaiting the next CEO of Carter’s as Michael Casey is retiring. Carter’s stock ($CRI) is pretty beaten up over the past year, down 30%. A possible macro problem for Carter’s is that the number of births in the United States appears to be declining.

It is powerful, when I’m changing my daughter, to contemplate my home town, and global commerce, and the people in Cambodia who made these clothes, and the ways of the world.

Reece Duca: fanatically reliant

Posted: August 27, 2024 Filed under: business Leave a commentBob Casey: You talk about the fact that there are a very small number of really exceptional companies. What do you mean by that?

Reece Duca: I rely on a study from–I believe his name’s Hendrick Bessembinder from Arizona State University– and what he did is he looked at every single public company from 1926 to 2016. So he covered a 90 year period. There were a total of 26,000 companies. And of the 26,000 companies, 25 of the 26,000 companies produced returns that are T-bill returns or less. So in other words, there was only 1000 companies that could create excess returns above risk-free T-bills returns.

Now you look at public companies, and you realize that companies can come public and because there’s a lot of incentives in the market, from whoever the constituent is, that their shareholders, their private equity holders, the investment bankers, whatever, you bring the companies public, but how many of them are exceptional companies? How many of them–and the reality is, most of them end up falling into that bucket that Professor Kay said, That’s the gray bucket. That’s the bucket of which, essentially, it’s the efficient market bucket.

And so, there’s only a tiny number of exceptional companies. And you understand that there’s some very specific things that permit exceptional companies to be sustainable decade after decade after decade. And many, many of them have to do with getting to the point where your customers are fanatically reliant, whether it’s a consumer product or whether it’s a business product, but your customers are fanatically reliant on what you deliver to them. If it’s a consumer product, it’s somebody is hooked on Coke, and they’re gonna drink coke come hell or high water. If it’s a business product, it gets locked into the workflow of the business, it’s something that your customers are ecstatic about. And that just essentially codified to us that what we needed to do, if we were going to have concentrated positions, we basically had to have super, super high confidence. And you had to find exceptional companies.

source. I was up in Santa Barbara so naturally reading about the local investment titan.

they work well until they catastrophically come off the rails

Posted: August 8, 2024 Filed under: business Leave a commentKEN GRIFFIN: “I don’t know what that moment will be, when there is an auction that goes awry, or when the markets become dislocated. Financial markets, generally speaking, work very well until they catastrophically come off the rails. You don’t necessarily get a lot of warning that there’s about to be a big event. The crash of ’87 is a great case study. That day, I woke up, I was in my dorm room trading then, and the stories of the day were about a small skirmish in the Middle East, of frankly no consequence, and the health of First Lady Nancy Reagan. And yet, we ended that day with the stock market down twenty-some percent, and a number of American financial institutions literally on life support or near death. It happened in one day. One day. There was no big story that morning that would make you think that that day might of been the end of the U.S. capital markets as we knew them. There was no warning. And so I worry that the debt crisis may have a similar construct. That there’ll simply be a day where a major auction fails, and then you see a panic start to brew in the Treasury market. And the question will be, how fast will the Fed intervene? What panic will that induce? Because government intervention under duress often creates more panic. And then do we see a flood of treasuries coming back into the market from holders around the world?

Bloomberg Live (YouTube) – May 14, 2024. That’s from Santangel’s Value Links.

Reminded of McMurtry on stampedes and crowd behavior.

Lyn Alden had this:

In the United States, there has been quite a big gap between haves and have-nots with this fiscal and monetary mix. Those who don’t have much assets, like mainly a house, have been largely locked out of owning assets. Meanwhile, those who have assets and who have locked in those low rates, are generally in great shape, save for the fact that many of them are now kind of “stuck” in their existing home. And since the top 50% of consumers spend a lot more than the bottom 50% of consumers, the fact that the top half is doing pretty well has been a strong engine for overall consumption.

strong engine for overall consumption.

What?

Posted: July 18, 2024 Filed under: beer, business Leave a comment

That’s from ValueLine. I’m long Diageo (Guinness has been popular for 250+ years and possesses pricing power, observe how few people buy the cheaper competitor Beamish) but I’m not seeing how putting on a VR helmet will help people experience tequila? Who is the dope here, Apple, Diageo, both? Feels degrading and cheap for both sides.

Quality data and Hapsburg AI

Posted: June 27, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, business Leave a commentThat’s from the June 7 issue of ValueLine. I subscribed after I saw this clip:

Not even sure what year that’s from.

Quality has been on my mind.

Quality … you know what it is, yet you don’t know what it is. But that’s self-contradictory. But some things are better than others, that is, they have more quality. But when you try to say what the quality is, apart from the things that have it, it all goes poof! There’s nothing to talk about. But if you can’t say what Quality is, how do you know what it is, or how do you know that it even exists? If no one knows what it is, then for all practical purposes it doesn’t exist at all. But for all practical purposes it really does exist. What else are the grades based on? Why else would people pay fortunes for some things and throw others in the trash pile? Obviously some things are better than others … but what’s the betterness? … So round and round you go, spinning mental wheels and nowhere finding anyplace to get traction. What the hell is Quality? What is it?

As the guy says in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. At the Smithsonian you can see Pirsig’s motorcycle:

I was at See’s Candy the other day:

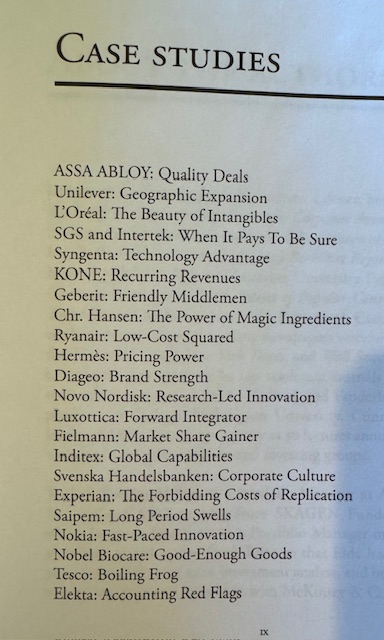

Recently I read this book:

There are some interesting case studies (although they skew a bit Euro):

Will AI ever produce something of “quality”? I have yet to see it.

C.R.A.V.E.D

Posted: May 14, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, food 1 Comment

continuing a deranged hobby of reading corporate materials for fast food companies. See if you can guess what the acronym C.R.A.V.E.D stands for at $JACK, the corporate parent of Jack In The Box and Del Taco.

To buy time while you think, here is a story about Herb Kelleher, founder of Southwest Airlines, who had a strong, clear mission focus:

There is a great story shared by Chip and Dan Heath in the book “Made to Stick” about the late founder Herb Kelleher. Kelleher once posed a question to someone about their strategy,

“Tracy from marketing comes into your office. She says her surveys indicate that the passengers might enjoy a light entree on the Houston to Las Vegas flight. All we offer is peanuts, and she thinks a nice chicken Caesar salad would be popular. What do you say?”

The person stammered for a moment, so Kelleher responded:

“You say, `Tracy, will adding that chicken Caesar salad make us THE low-fare airline from Houston to Las Vegas? Because if it doesn’t help us become the unchallenged low-fare airline, we’re not serving any damn chicken salad.’

(source)

Warren Buffett on love

Posted: April 14, 2024 Filed under: business, how to live, love Leave a commentAfter visiting [his wife Susan] in hospital, he told a class at Georgia Tech, “When you get to my age, you’ll really measure your success in life by how many of the people you want to have love you actually love you. I know people who have a lot of money, and they get testimonial dinners and they get hospital wings named after them. But the truth is that nobody in the world loves them. If you get to my age in life and nobody thinks well of you, I don’t care how big your bank account is, your life is a disaster. That’s the ultimate test of how you have lived your life.” He continued, “The trouble with love is that you can’t buy it. You can buy sex. You can buy testimonial dinners. You can buy pamphlets that say how wonderful you are. But the only way to get love is to be lovable. It’s very irritating if you have a lot of money. You’d like to think you could write a check: I’ll buy a million dollars’ worth of love. But it doesn’t work that way. The more you give love away, the more you get.” Of all the lessons that Warren has taught me, perhaps this is the most important.

from Education of a Value Investor by Guy Spier.

If you keep Jimmy Buffett and Warren Buffett as navigational beacons, you’ll probably have an ok ride.

Prorsum

Posted: April 9, 2024 Filed under: business, mountains Leave a comment

went looking into Burberry, the English clothing brand, famous for their iconic plaid.

Prorsum, on their logo, a Latin form: towards, forwards.

Turns out Burberry made a movie about Thomas Burberry:

Thomas Burberry invented the fabric gabardine and revived the name (which had been used in the Middle Ages to describe, like, overcoats). Mallory was wearing gabardine when he died trying to summit Mount Everest (he still is wearing gabardine. If you’re morbid, you can find photos of his body and see how well the Burberry is holding up after a hundred+ years).

Sysco

Posted: April 5, 2024 Filed under: business Leave a commentYou’ve probably seen a Sysco truck around, they’re a massive wholesale food distribution company. They’re mentioned a few times in Kent Taylor’s book, so I looked into the company. Here’s their CEO:

I thought this was funny:

When you click:

Kent Taylor, Made From Scratch

Posted: March 30, 2024 Filed under: business, food Leave a comment

Kent Taylor was a spectator at the 1971 NCAA cross-country championships:

I will never forget [Steve] Prefontaine powering through that tough hilly course, challenging anyone to catch him as he picked up the pace on each rise, daring all comers to endure pain only he was capable of enduring. Steve won the race, no problem, and wore about him afterward an aura of extreme confidence that captivated me. Still, to this day, I can remember that look, as if he wanted his challengers to bring on whatever they had, and he’d find a way to bring that much more.

Kent Taylor was a skinny kid who was kicked off the football team by a coach who told him he might die out there. He went into track and cross country and drove himself to become better. One summer he trained by running over a thousand miles. He got good enough that with some persistence and luck he got a partial scholarship to UNC. There he ran the steeplechase, obstacle running complete with a water hazard.

Kent Taylor had drive. After college he moved back to Louisville, managed some nightclubs in Cincinnati, managed a Bennigan’s in Dallas for a bit, worked for KFC. What he wanted to do was launch his own concept for a restaurant: Texas Roadhouse.

My initial thought regarding Texas Roadhouse was to combine a rough and somewhat rowdy live music joint with a reasonably priced restaurant featuring steaks and ribs. I wanted to have the same quality of beef that Outback and Longhorn featured at the time, but with price points more similar to Chili’s and Applebee’s. I wanted to target the blue-collar segment of America (my peeps) who would be comfortable with jukebox country music and a casual and lively atmosphere with energetic servers in jeans and T-shirts. In short: Baby, if you want to dress up, then visit somewhere else; but if you want to dress down, we would welcome you with open arms and a warm smile.

Two of his first investors were Dr. Amar Desai and Dr. Mahendra Patel. The concept sparked but there were bumps. Kent opened the second restaurant in Gainesville, Florida 700 miles away from the first one because he had good memories of Gainesville. Three of the first five restaurants failed. But Kent Taylor and the Roadhouse team started to figure it out:

Another idea was to offer free rolls. We played around with giving out popcorn, something for people to munch on immediately, but realized we wanted the smell of rolls to hit our guests when they walked in. If we were going to offer them, though, I wanted to get the recipe perfect. I set my assistant kitchen manager, Rod, to driving all over town to buy as many types of flour and yeast as he could find. We then experimented. Rod and I would try this type of flour with this type of yeast, adding so much water, so much oil, and a dash of sugar and a few other ingredients for good measure. Then we tried again. We also experimented with dozens of variations to proof and bake the rolls. Nothing tasted right. I wanted a fairly sweet roll, but sugar and yeast fight each other, so I needed a flour that would work with both. The process of discovering the best Roadhouse rolls consumed our waking days for three weeks. I’m pretty sure it also consumed Rod’s sleep. He probably dropped off at night counting bags of flour. I was tormenting the poor guy with my relentless pursuit of the perfect roll. Finally, we hit it when we mixed a certain flour with another flour. The mix came together in no time and we created the rolls we use to this day. Our honey cinnamon butter followed a similar process, eventually finding positive results.

Kent had a vision for restaurants that was something like Wagner’s for opera*. He wanted immersive, overpowering. The word Legendary, that’s key. Legendary food, legendary service, legendary margaritas. Texas Roadhouse is full of wood and tin: Kent wanted it loud. Big neon signs on the places are the only advertising. Texas Roadhouses don’t open for lunch** because Kent Taylor envisioned one big, energized shift, almost a performance

We had the chargrills visible to the guests, a meat display case to view our freshly butchered steaks, and you could smell the steaks cooking and the freshly baked bread coming out of the oven. The six senses would come alive for our guests—sight, smell, taste, hearing, and touch. The sixth sense was a feeling of a warm and friendly vibe.

It worked. There are 741 Texas Roadhouse restaurants in 49 countries. The nearest one to LA would be either Rialto or Corona, CA. This makes sense: LA real estate is expensive and Texas Roadhouse knows to their customer every dollar matters. Being involved in the community is part of the business model and the Kent Taylor vision.

On a recent trip down the 10, we stopped at the Rialto location. It was just after opening time (3pm) and there was already a 20 minute wait. It was all there, just as Kent described. Friendly people, country music, wood and tin. The sweet rolls with the cinnamon honey butter are brought to your table as you sit down. Bag of peanuts waiting for you. No server has more than three stations so they’re on top of it. We signed up for the Texas Roadhouse VIP Club beforehand, which merits you a free appetizer: we got rattlesnake bites of course, delicious. Part of the popularity might be the $13.99 Early Dine Menu. You’re getting a steak dinner for under $14. Tried the Legendary Margarita, and it was a lot of fun. By the time we left every seat at the bar was occupied. There were big families, elderly couples, hard-work looking dudes having some cold ones.

Kent Taylor in this book comes through as such a boosterish, positive person that it’s hard to grapple with his end. From The Wall Street Journal, March 2021:

After coming down with a mild case of Covid-19, W. Kent Taylor found himself tormented by tinnitus, a ringing in the ears. It persisted and grew so distracting that the founder and chief executive of the restaurant chain Texas Roadhouse Inc. had trouble reading or concentrating.

Mr. Taylor told one friend he hadn’t been able to sleep more than two hours a night for months.

In early March, he met friends at his home in Naples, Fla., and led them on a yacht cruise in the Bahamas. Some of those friends thought he was finally getting better. Then his tinnitus “came screaming back in his head” last week, said Steve Ortiz, a longtime friend and former colleague.

On Thursday, March 18, Mr. Taylor died by suicide in his hometown of Louisville, KY.

Very sad. But his vision lives on. I predict Texas Roadhouse will continue to succeed as long as they remember the lessons of founder Kent Taylor. He’d seen what happens when you lose that:

The decline of Bennigan’s was another wake-up call to keep our standards sky-high and not slip into corporate-think. Thankfully, our company is run by people who have grown up in actual restaurant operations and many were eyewitnesses to either Chi-Chi’s or Bennigan’s’ demise.

* not that Kent would use this comparison. He preferred: Willie Nelson, Three Doors Down, Keith Urban, Kenny Chesney, Aerosmith, etc. Mentioning who played at which corporate celebrations is a big part of the book

** some of them do open for lunch one day a week, usually Friday or Saturday

A lunch in Florida

Posted: March 23, 2024 Filed under: business | Tags: art, books, disney, travel Leave a comment

Not sure we’ve ever seen the kind of shade on a restaurant as Harriet Agnew provides in the latest Lunch w Financial Times, with Nelson Peltz, at his own restaurant:

It’s the proprietor’s prerogative — Peltz’s 19-year-old investment firm, Trian Partners, owns the building and the Italian restaurant is their de facto canteen. Soon the elevator-style music quietens down and we settle at our table on the outdoor terrace

Peltz declines wine – always a bad sign in Lunch FT:

As we begin our starters — slightly flavourless mozzarella and tomato in need of seasoning, with roasted peppers — Peltz tells the story of Triangle Industries, his focus in the 1980s. Fuelled by the junk bonds of his friend Michael Milken, he and his business partner Peter May built it into the largest packaging company in the world, before selling it. They later bought and lucratively sold the Snapple beverage business.

They talk about Peltz’s campaign to win a contested fight for some board seats at Disney (asked if he would fire Kevin Feige, who masterminded like 60 winning Marvel movies, he doesn’t say yes but expresses displeasure):

By now our main course has arrived: filleted snapper in a gloopy artichoke, mushroom, tomato and white wine sauce, served with sautéed spinach.

In terms of lunch, it doesn’t seem billionaires have it that much better. Here’s a link.

Publicly traded American restaurant groups

Posted: March 22, 2024 Filed under: business, food 1 Comment

Bloomin Brands (ticker symbol: BLMN) owns Outback Steakhouse and Fleming’s. 50 new Outback Steakhouses opened in Brazil since 2021.

There are 3,427 Chipotles (CMG) in the United States, with 97,660 employees. Here’s Slate recently on Chipotle’s dominance:

But despite that backlash, the fact remains that for a lot of Americans, from San Diego to New Haven and everywhere in between, Chipotle has become effectively synonymous with good Mexican eating. When the Wall Street Journal interviewed Mary Hawkins, the mayor of Madison, Mississippi—one of the tiny population centers Chipotle has in its sights—she said the town had recently polled its citizenry about the brands it would most like to see take up residence on its streets. Chipotle, perhaps unsurprisingly, came in first, and Arellano does not see that trend slowing down.

“It’s like Galactus from Marvel Comics. It’s eating up burrito cultures from across the country,” he said. “Chipotle taught an entire generation of Americans to eat a very specific style of burrito. If they want a burrito, they’re going to want the one they grew up with and neglect the other styles.”

McDonald’s (MCD) of course is the king, with 42,000 stores. Here’s Ian Borden, McDonald’s CFO, being interviewed at a UBS conference:

Dennis Geiger

That’s great. Want to go over to core menu. And you just talked about some of the opportunities at chicken I think in particular. As we think about beef, chicken and coffee and some of the biggest opportunities to kind of further your advantages on core menu anything else to kind of highlight there across those key equities?

Ian Borden

Yes. Sure. Well look I talked about core is critically important. 65% of our global system-wide sales, $17 billion brands across that core categories and I think a few headlines under each of those three. Beef obviously we’re by far the largest player in beef globally. We’ve gained share since 2019 pretty consistently across our markets. I think a couple of the key things from an opportunity standpoint in beef. Best Burger which is just a series of what I’ll call small changes in how we cook and prepare our core beef products that’s been out to about 70 markets. It’s going to be in the rest of the system by end of 2026. It’s driving significant improvements in taste and quality. Taste and quality are the two biggest drivers of consumer visits to our restaurants. So that’s impactful.

The second thing on beef that I think is worth highlighting is the opportunity we see around large burger. And it’s a good example of how I think we are more precisely understanding consumer need and then getting after that consumer need and I’ll call it a one-way approach. So we’ve tried to get after this opportunity for a number of years because we thought the opportunity was about premium burger which was wrong. And we — so we didn’t — we weren’t successful. We now understand what the opportunity is for a large more satiating-type burger. That opportunity is significant. It’s consistent across many of our large markets.

And we have innovated a couple of products that we’re in the process of piloting. We’re going to pilot those products in two or three what we call market zeros. We’re then going to — if those products work we’re then going to scale one solution to that opportunity globally where in the past you would have seen us probably try and get after that opportunity in 20 different markets in 20 different ways and then you don’t have the ability to build a global equity that you can drive at scale. So that’s a little bit about beef.

McDonald’s is essentially a real estate company with a restaurant system they can affix and then turn over to franchisees.

The Darden Group (DRI) owns: Ruth’s Chris Steak House, Eddie V’s and The Capital Grille, Olive Garden Italian Restaurant, LongHorn Steakhouse, Bahama Breeze, Seasons 52, Yard House and Cheddar’s Scratch Kitchen. Until July 28, 2014, Darden also owned Red Lobster. Darden has more than 1,800 restaurant locations and more than 175,000 employees, making it the world’s largest full-service restaurant company. (says Wikipedia). There are 77 Ruth’s Chris and 562 Longhorn Steakhouses.

Brinker (EAT) has Chili’s and Maggiano’s Italian Grill. They’re having a killer year, surprising to me to learn, as the local Maggiano’s is closed and troughs of Italian slop don’t seem in fashion. But my heart still warms at the thought of Chili’s. Norman Brinker was a pioneer of the casual dining space.

Dine (DIN) owns IHOP (1,787 restaurants), Applebee’s (1,654) and Fuzzy’s Taco Shop (137 branches). The local IHOP near me is closing. A few years ago I tried an Applebee’s and was dissatisfied with the experience. I’ve never even seen a Fuzzy’s. As for pancakes, feels like they peaked as a food in like 1880?

Domino’s has 20,197 franchises. Their stock (DPZ) over the last twenty years returned investors something like 2,600% (vs 239% for the S&P 500). The key is the easy to use app.

Restaurant Brands International (QSR) has Burger King, Tim Horton’s, Popeyes, and Firehouse Subs, for a total fo 30,375 franchises. Noted investor and Harvard administration gadfly Bill Ackman has a big position in QSR, as well as Chipotle. In his recent Lex Friedman podcast he noted that some of his biggest wins have been in restaurants.

Shake Shack (SHAK) has expanded very fast, they now have 440 stores. I remember going to the very first branch in the summer of 2009, before starting my new job on 30 Rock. Who was in line behind me but Scott Adsit?!

Texas Roadhouse (TXRH) is booming, returning 738% for investors since founding. The story of founder W. Kent Taylor is worthy of its own post, when I have the time. I listened to a couple podcasts, one with Jerry Morgan, current CEO and one with VP of communications Travis Doster, and they project a “fun with purpose” coherent and vigorous company culture inspired by Kent Taylor’s vision.

Starbucks (SBUX) has 10,628 company owned stores and 18,216 licensed. Personally I consider that a drug dispensary rather than a restaurant.

Wendy’s (WEN) has 7,095 restaurants worldwide. Their new CEO Kirk Tanner made some noise recently with his comments about AI order-taking and flexible pricing, which the company then walked back. It sounded kinda fun to me (what if you could get a deal at an off hour or something) and made for many a meme. Kirk Tanner seems to get in the news a lot: Wendy’s doing drone delivery was a headline on Drudge the other day. Those all seem like distractions or possibly stunts? Wendy’s big play at the moment is expanding into breakfast.

Wingstop (WING) is growing fast: 1,996 restaurants. The stock has doubled in the last year. The people love wings!

Yum Brands (YUM) with KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and Habit Burger is on another level. They opened 4,754 new units last year.

Jack in the Box (JACK) swallowed Del Taco a few years ago. Here’s CEO Darin Harris speaking about the culture of servant leadership. I like what I hear!

New York hot dog chain Nathan’s and Chicago hot dog chain Portillo’s are both public companies, NATH and PTLO respectively. I’m not bullish on the future of hot dogs myself. If I were on the board of Nathan’s (I’m not) I’d lean into the hot dog eating contest aspect. That could be completely the wrong way to go, who knows, but they’ve got to take a swing.

I’ve never seen a Kura Sushi, but some investors appear to be optimistic about the technology-enabled Japanese sushi concept – the stock (KRUS) is up 41% this year.

Casey’s (CASY) runs some 2,500 gas station pizza joints in the Midwest. The Casey’s in Corning, Iowa was the only place to eat one Sunday night last summer. It was not bad at all! Iowan amigo Brooks tells me it’s beloved, that you should try the sausage pizza. Not much more is easily available to me on founder Donald Lamberti other than that he is in the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame. “Kind of a monopoly on many, many tiny markets”? A growing business.

Flanigan’s (BDL) is a Florida chain famed for their dolphin sandwich (don’t stress, it’s actually mahi mahi). Why it’s publicly traded doesn’t make sense to me, but there you go. I’ve never been, I collected a firsthand report or two that suggested it’s a real good time, if not necessarily Wall Street’s most ambitious concern.

Some amateur investor types love RCI, aka Rick’s (RICK), a chain of strip clubs, on the thesis that it’s kind of hard to launch a new strip club, as nobody wants ’em in their neighborhood. I’m not sure Bombshells counts as restaurants, but a publicy traded strip club joint with an expressive CEO is a noteworthy indicator.

Anyone been to a Chuy’s (CHUY)?

On May 31, 2001, then President George W. Bush’s twin daughters, Jenna Bush and Barbara Bush, were cited for using fake IDs at the Barton Springs Road Chuy’s, which put Chuy’s in the national spotlight

Next time in Austin maybe. What’s the gameplan for Chuy’s? From their recent earnings call:

As we look ahead, we will continue to do what we do best to provide our guests with fresh, made from scratch food and drinks at an incredible value. Despite weather issues across the country that has impacted the restaurant industry in January, we believe the initiatives we put in place to drive long-term sustainable top line growth and profitability has positioned us well to weather these near-term challenges.

With that, let me provide some update on our growth drivers. Starting with menu innovation. As we mentioned on our last call, we introduced our first barbell approach to the CKO platform during the fourth quarter, and we were very pleased with how well it was received by our guests. In fact, this was our second most successful Chuy’s Knockouts campaign to-date.

Following this success, we were thrilled to introduce to our guests the next CKO iteration in late January with Shrimp & Crab Enchiladas with Lobster Bisque sauce as a higher-priced CKO menu item, along with Macho Nachos and the Cheesy Pig Burrito. Again, early feedback continues to be positive as our CKOs are resonating well with both new and returning guests.

Alongside our exciting CKO offering, we recently added several new menu items to our permanent menu, including reintroducing the Appetizer Plate and adding the Burrito Bowls. If you recall, Burrito Bowls were part of our CKO platform during the second and third quarter of 2023 and this menu

etc etc. Good luck Chuy’s!

And of course, Cheesecake Factory (CAKE), much mocked, but enduring. Ate there the other day with some colleagues. You know what? My Santa Fe Salad was good. What do we think of this?:

Much lunch conversation turned on this.

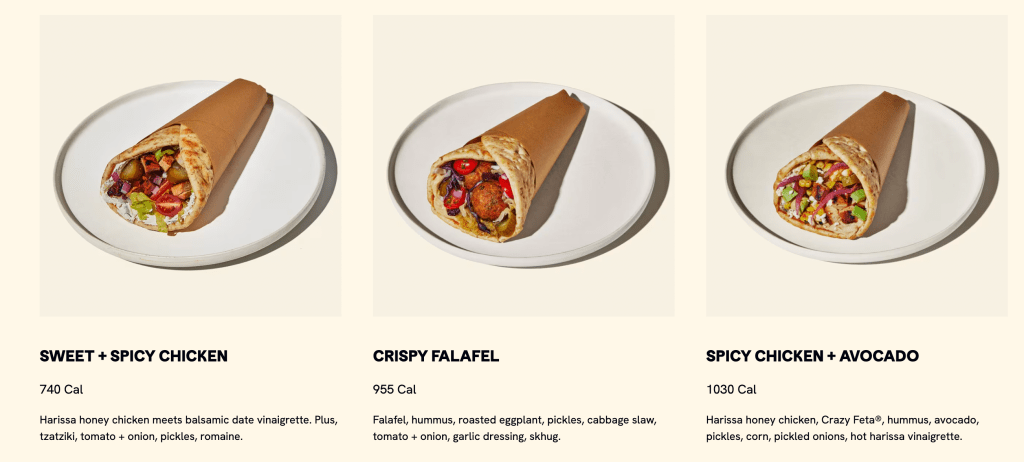

CAVA is a new Mediterranean restaurant concept from the East Coast. A new one appeared here in LA. I tried it. Their operating system was not perfect (in fairness, think this is a new branch). Kinda salty?

The stock seems to excite investors, possibly because everyone is looking for “the next Chipotle.” Appears to be up 5% just today! I checked in with one of my Vibes Reporters:

i have had cava once. ok but didnt feel the need to go back

Kinda how I felt? The pita chips are fun. I just don’t think Mediterranean food will have quite the appeal of Chipotle.

Sweetgreen (SG) is a salad deal, I’ve tried that one. Somehow, I always feel gross afterwards.

On the other end of the spectrum is Cracker Barrel (CBRL) serving Southern-inspired slop to old people. Valueline reports:

Macroeconomic factors have impacted Cracker Barrel Old Country Store’s sales. Elevated inflation, though now apparently easing, has stressed the company’s customers. Many of these customers are in the 65-and-older demographic, commonly characterized as a fixed-income category. Management is working to bring in more of a younger crowd into Cracker Barrel restaurants and in-location retail shops,

Good luck guys, but this looks to me like the past, not the future:

Then again, Cracker Barrel has (had?) their loyalists:

From 1977 to 2017, married couple Ray and Wilma Yoder drove a combined total of more than 5 million miles (an average of 342 miles per day) to visit 644 Cracker Barrel locations. When the company opened their 645th restaurant, in Tualatin, Oregon, in August 2017 (on Ray Yoder’s 81st birthday), it flew the Yoders out for the grand opening and presented them with custom aprons and rocking chairs, among other gifts.[52][53]

Yoshiharu (YOSH) is a Southern California ramen concept I have yet to try. There’s also Noodles & Company (NDLS). Why is their ticker symbol not NOOD? Missed opportunity. The noodles game seems too competitive to me, talk about low margins.

But then again look at the big winners here: MCD, DPZ, CMG. Burgers, pizza, burritos. You couldn’t come up with businesses with more competition, no barriers to entry. And yet these three systematized delivery and managed quality control in such a way as to create unstoppable empires.

I began this post as I was reading Value Line’s restaurant issue and enjoying contemplating the massive scale of these restaurant chains. As an occasional restaurant consumer I can engage with these places and sense their vibe, it’s a sector I can know in a way I can’t know, say, semiconductors or industrial products. So it’s an engaging, practical and delicious topic for our continued education in business.

Restaurant Business might be the next frontier to explore. They have a daily podcast!

Growing at exactly the right pace and to exactly the right size seems like the key for restaurant stocks. On his Invest Like The Best podcast, Patrick O’Shaughnessy interviewed Capital Management’s Anne-Marie Peterson. She talked restaurants:

So restaurants are different from retail because it’s not as easy to scale. There aren’t a bunch of large cap restaurant chains unlike retail. The franchise model is pretty powerful and what Chipotle has done is pretty powerful, too. But the similarities are like real estate matters, the store experience matters. But in a tight labor market, it’s tough.

And what’s interesting about McDonald’s — I have such an affection for that company. It works everywhere. They have one concept. I think it’s 60% or 70% of their operating income is from rent. They’re a landlord. They control the real estate. The others didn’t, so that’s why they’ve endured. They had a big insight about like let’s own the real estates so our franchisees don’t get whipped around with pricing, and we can co-invest with them in the experience.

And now digitals. The mobile ordering is enhancing the productivity and reducing even those kiosks. That need for labor and in a tight labor market, it’s big. The little guys can’t invest. They have some external dynamics now that are contributing to scale. But it’s really interesting.

Rory Sutherland brought up McDonald’s automated screens on Rick Rubin’s Tetragrammaton podcast. He wondered if they might allow for customers to make certain shameful orders they feel bad about saying to a person. I’ve tried out the automated screens, they work great at getting you your junk, but they make the world a little less human.

Remember when Eric Schlosser’s book Fast Food Nation came out in 2001? Absolutely everybody was reading it. They made a movie (pretty good! Richard Linklater). Yet here we are, almost twenty five years later, eating more fast food than ever.

I was reading The Lorax to baby and it reminded me of Schlosser.

Here’s a more comprehensive list of restaurant stocks as I’ve skipped a few, notably Denny’s (DENN, slumping), Red Robin (RRGB, hopeless), El Pollo Loco (LOCO, stop trying to make citrus-marinated chicken happen), BJs, a few others.

“Treat” shops such as Krispy Kreme are beyond the scope of this post.