Henry Adams on Harvard in 1800

Posted: October 23, 2025 Filed under: New England Leave a comment

from Garry Wills, Henry Adams and the Making of America, a must for Adams-heads.

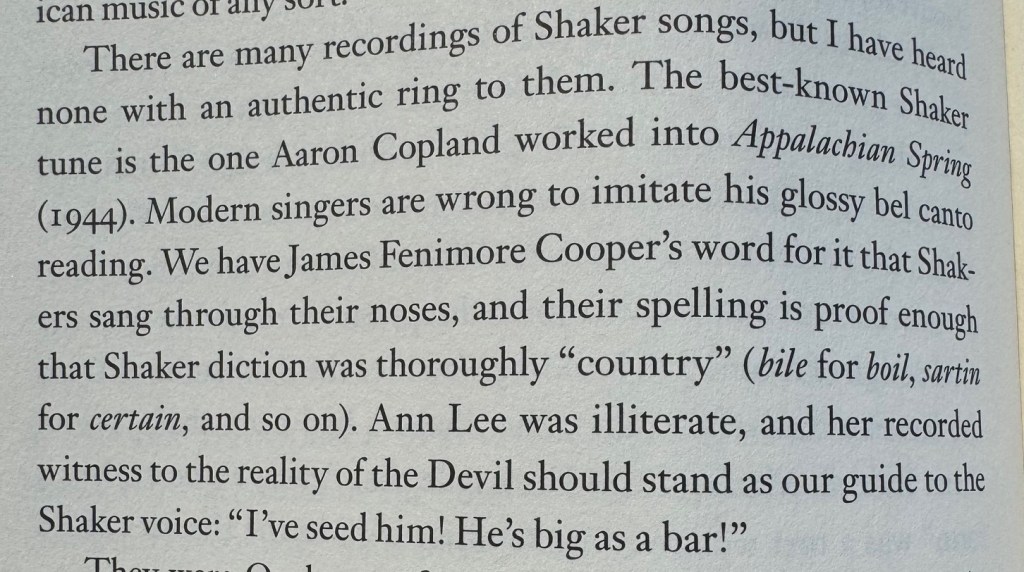

The Hunter Gracchus by Guy Davenport

Posted: October 20, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, New England Leave a commentRevisited this one after seeing some footage from The Testament of Ann Lee.

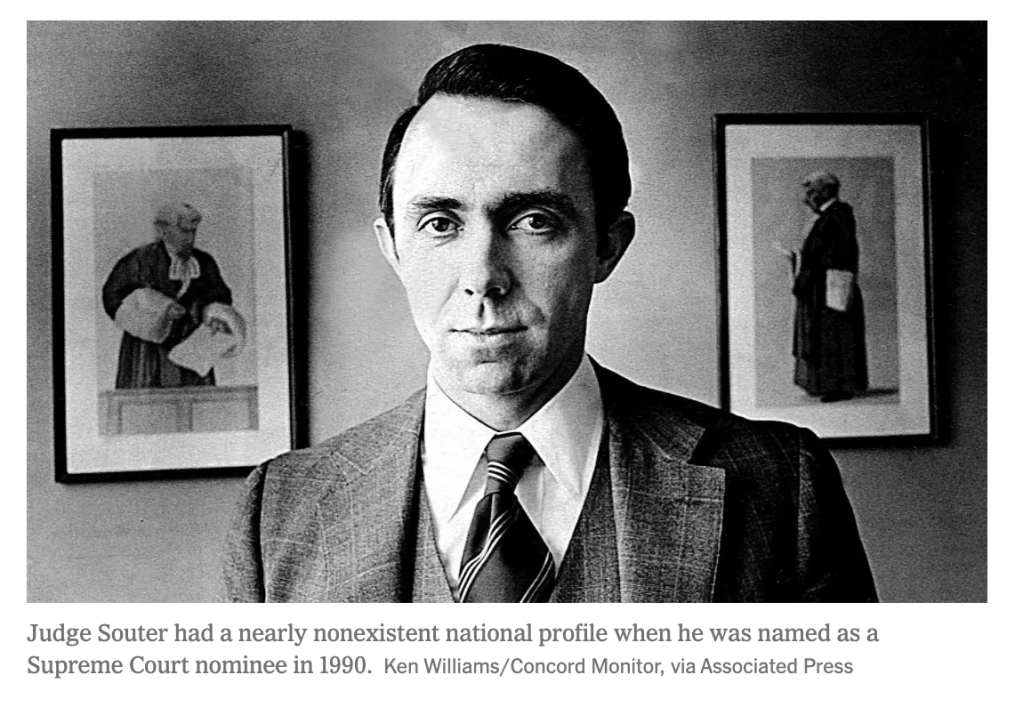

David Souter

Posted: May 10, 2025 Filed under: Boston, New England Leave a comment

None of this [Washington eminence] held any appeal for David Souter, who after returning home from his Rhodes scholarship at Magdalen College, Oxford, crossed the Atlantic only once again, for a reunion there. Who needed Paris if you had Boston, he would remark to friends. When the court is in recess, he gets in his Volkswagen and heads to Weare, N.H., to the small farmhouse that was home to his parents and grandparents.

from a 2009 NYT consideration of Souter by Linda Greenhouse.

I remember reading that remark when I was a kid, maybe in Alex Beam’s column in The Boston Globe. I’ve sometimes thought that myself when back in Boston. Although I’m usually back in the spring or fall. I don’t think too many people think that in February.

When I look at my (rare) photographs I never seem to quite capture the magic.

A shy man who never married and who much preferred an evening alone with a good book to a night in the company of Washington insiders, Justice Souter retired at the unusually young age of 69 to return to his beloved home state.

We need more of this. I’m reading his obituary and Charles Grassley, who was at Souter’s confirmation hearing, is still a damn senator!

After he retired, Justice Souter sold the family farmhouse and moved to a home he bought in nearby Hopkinton. The reason, he explained, was his large book collection, which the old farmhouse could neither hold nor structurally support. Reading history remained a cherished pastime. “History,” he once explained, “provides an antidote to cynicism about the past.”

One of the best aspects of Boston is that it’s one big history book.

Carter’s, congealed electricity, AI and Needham

Posted: January 30, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, children, New England, Uncategorized Leave a comment

If you have a little kid in the US you will have some clothes from Carter’s. They sell them at Target and Wal-Mart as well as 1,000 or so Carter’s stores, and they cost $8.

Before I had a kid it didn’t occur to me that kids outgrow their clothes so fast they can’t cost too much.

When I see the Carter’s label, I think of my home town.

William Carter founded Carter’s in Needham, Massachusetts in 1865. Textiles were a big business in New England. Two inputs, labor and electricity, were cheap. Labor from excess farm children, and electricity from running streams? That would’ve been the earliest mode, what were they using by 1865? Coal?

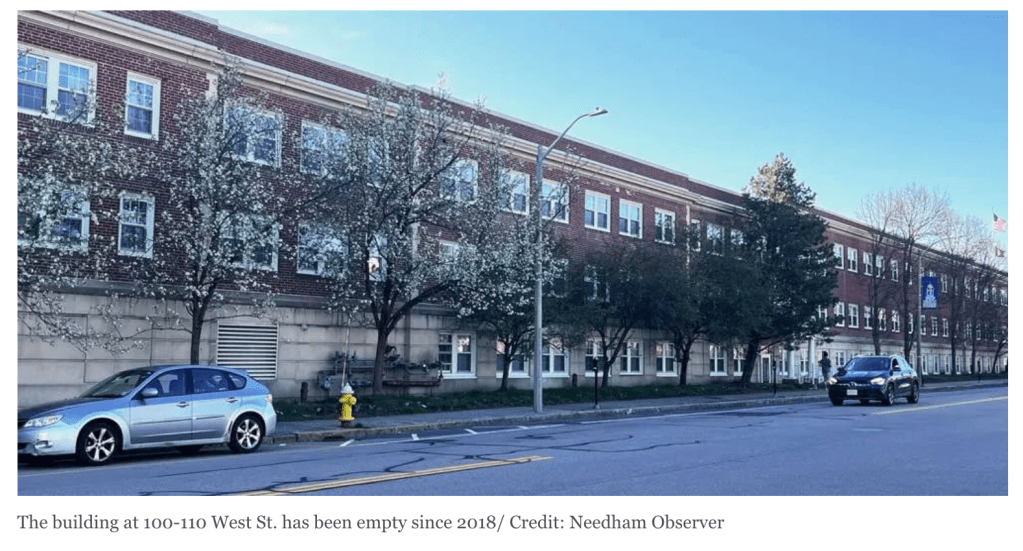

One of the biggest buildings in Needham, certainly the longest, is the former Carter’s headquarters, which stretches itself along Highland Avenue. A prominent landmark, it took a long time to walk past.

The story of Carter’s is a global economic story in miniature.

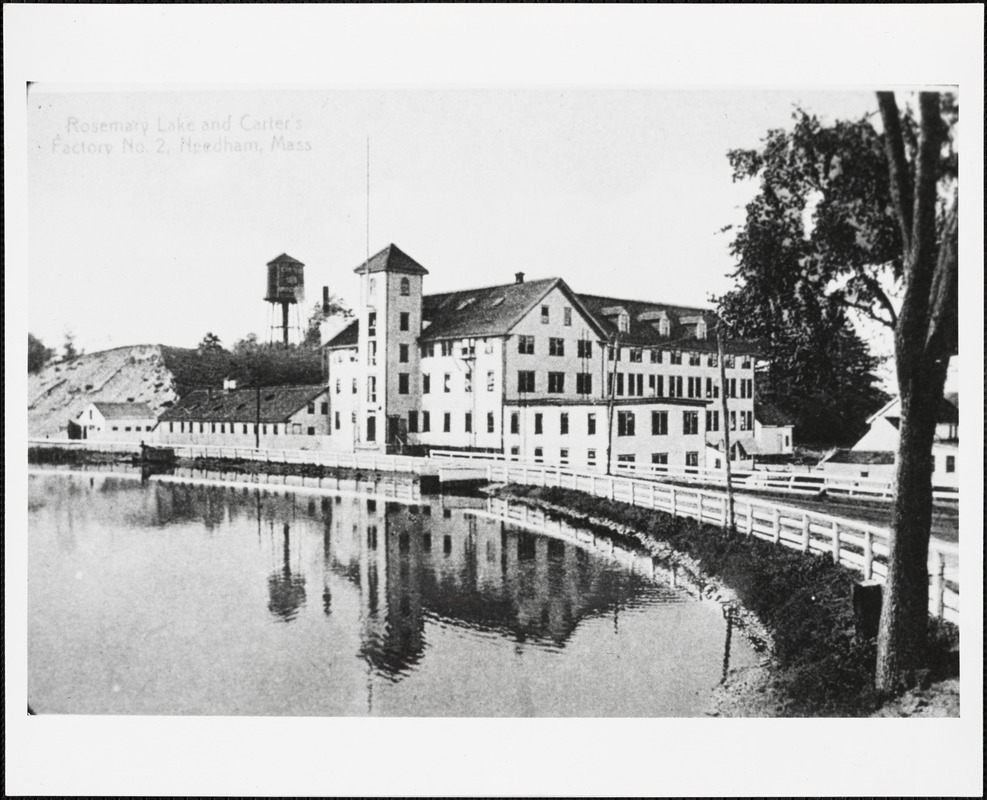

Old Carter mill #2, found here.

The Carter family sold the company in the 1990s. It went public in 2003. In 2005, Carter’s acquired OshKosh B’gosh, a company famous for making children’s overalls. This company started in 1895 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin (the name comes from an Ojibwe word, “The Claw,” that was the name of a local chief).

The term “B’gosh” began being used in 1911, after general manager William Pollock heard the tagline “Oshkosh B’Gosh” in a vaudeville routine in New York.[4] The company formally adopted the name OshKosh B’gosh in 1937.

OshKosh B’Gosh’s Wisconsin plant was closed in 1997. Downsizing of domestic operations and massive outsourcing and manufacturing at Mexican and Honduran subsidiaries saw the domestic manufacturing share drop below 10 percent by the year 2000.

OshKosh B’Gosh was sold to Carter’s, another clothing manufacturer for $312 million

The headquarters of Carter’s moved to Atlanta. Labor and electricity were cheaper in Georgia, Carter’s had been opening mills in the South for awhile. Now the clothes are made overseas. I look at the labels on Carter’s clothes: Bangladesh, India, Cambodia, Vietnam. If you factor in the shipping and the markup how much of that $8 is going to your garment maker in Bangladesh? Then again maybe it’s the best job around, raising Bangladeshis out of poverty, and soon Chittagong will look like Needham.

The former Carter’s headquarters, now vacant, became a facility for elder living. My mom worked there, briefly. Carter’s today is headquarted in the Phipps Tower in Buckhead, Atlanta, which I happened to pass by the other day.

The loss of the mill and the company headquarters was not a crisis for Needham. Needham is very close to Boston, an easy train ride away, and along of the 128 Corridor. There are growth businesses in the area, hospitals, biotech companies, universities. TripAdvisor is based in Needham. Needham is a pleasant town, there are ongoing talks to turn the former Carter’s building into housing. It would be close to public transport and walkable to the library and the Trader Joe’s. That seems to be stalled.

Needham has brain jobs, attached to a dense brain network, while brawn jobs are being shipped overseas. There are many other towns in Massachusetts where the old run down mill is a sad derelict as production moved first south and then overseas. These towns are bleak. Oshkosh, Wisconsin seems ok, but the shipping of steady jobs overseas is of course a major factor in our politics, Ross Perot was talking about it in 1992 and no one did anything about it and now Trump is the president.

A similar story lies in the history of Berkshire Hathaway – the original New Bedford textile mill, not the conglomerate Warren Buffett built on top of it using the same name. Buffett talks about this, I believe this is from the 2022 annual meeting:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I remember when you had a textile mill —

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, god.

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and it couldn’t —

WARREN BUFFETT: I try to forget it. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and the textiles are really just congealed electricity, the way modern technology works.

And the TVA rates were 60% lower than the rates in New England. It was an absolutely hopeless hand, and you had the sense to fold it.

WARREN BUFFETT: Twenty-five years later, yeah. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, you didn’t pour more money into it.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, that’s right.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And, no — recognizing reality, when it’s really awful, and taking appropriate action, just involves, often, just the most elementary good sense.

How in the hell can you run a textile mill in New England when your competitors are paying way lower power rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: And I’ll tell you another problem with it, too. I mean, the fellow that I put in to run it was a really good guy. I mean, he was 100% honest with me in every way. And he was a decent human being, and he knew textiles.

And if he’d been a jerk, it would have been a lot easier. I would have probably thought differently about it.

But we just stumbled along for a while. And then, you know, we got lucky that Jack Ringwalt decided to sell his insurance company [National Indemnity] and we did this and that.

But I even bought a second textile company in New Hampshire, I mean, I don’t know how many — seven or eight years later.

I’m going to talk some about dumb decisions, maybe after lunch we’ll do it a little.

Congealed electricity, what a phrase. In the 1985 annual letter, Buffett discusses the other input, labor, which was cheaper in the South, and why he kept Berkshire Hathaway running in Massachusetts anyway:

At the time we made our purchase, southern textile plants – largely non-union – were believed to have an important competitive advantage. Most northern textile operations had closed and many people thought we would liquidate our business as well.

We felt, however, that the business would be run much betterby a long-time employee whom. we immediately selected to be president, Ken Chace. In this respect we were 100% correct: Ken

and his recent successor, Garry Morrison, have been excellent managers, every bit the equal of managers at our more profitable businesses.… the domestic textile industry operates in a commodity business, competing in a world market in which substantial excess capacity exists. Much of the trouble we experienced was attributable, both directly and indirectly, to competition from foreign countries whose workers are paid a small fraction of the U.S. minimum wage. But that in no way means that our labor force deserves any blame for our closing. In fact, in comparison with employees of American industry generally, our workers were poorly paid, as has been the case throughout the textile business. In contract negotiations, union leaders and members were sensitive to our disadvantageous cost position and did not push for unrealistic wage increases or unproductive work practices. To the contrary, they tried just as hard as we did to keep us competitive. Even during our liquidation period they performed superbly. (Ironically, we would have been better off financially if our union had behaved unreasonably some years ago; we then would have recognized the impossible future that we faced, promptly closed down, and avoided significant future losses.)

Buffett goes on, if you care to read it, to discuss the dismal spiral faced by another New England textile company, Burlington.

Charlie Munger, in his 1994 USC talk, spoke on the paradoxes here:

For example, when we were in the textile business, which is a terrible commodity business, we were making low-end textiles—which are a real commodity product. And one day, the people came to Warren and said, ‘They’ve invented a new loom that we think will do twice as much work as our old ones.’

And Warren said, ‘Gee, I hope this doesn’t work because if it does, I’m going to close the mill.’ And he meant it.

What was he thinking? He was thinking, ‘It’s a lousy business. We’re earning substandard returns and keeping it open just to be nice to the elderly workers. But we’re not going to put huge amounts of new capital into a lousy business.’

And he knew that the huge productivity increases that would come from a better machine introduced into the production of a commodity product would all go to the benefit of the buyers of the textiles. Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.

That’s such an obvious concept—that there are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Is something similar happening with AI? Who will it make rich, and at what cost? To whose ribs will the profits stick?

I’m not sure we could call AI congealed but it is more or less just more and more electricity run through expensive processors. Who will win from that? So far it’s been the makers of the processors, but if DeepSeek shows you don’t need as many of those the game is changed. Personally I’m unimpressed with DeepSeek – try asking it what happened in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

How does Carter’s itself continue to survive? Target’s own brand, Cat & Jack, is right next door on the shelves. Could another company shove Carter’s aside if they can cut the margins even thinner, get the price down to $7? Here’s what Carter’s CEO Michael Casey has to say in their most recent annual letter:

Hard to build the operational network Carter’s has over 150+ years. There will be a challenge awaiting the next CEO of Carter’s as Michael Casey is retiring. Carter’s stock ($CRI) is pretty beaten up over the past year, down 30%. A possible macro problem for Carter’s is that the number of births in the United States appears to be declining.

It is powerful, when I’m changing my daughter, to contemplate my home town, and global commerce, and the people in Cambodia who made these clothes, and the ways of the world.

Tempted

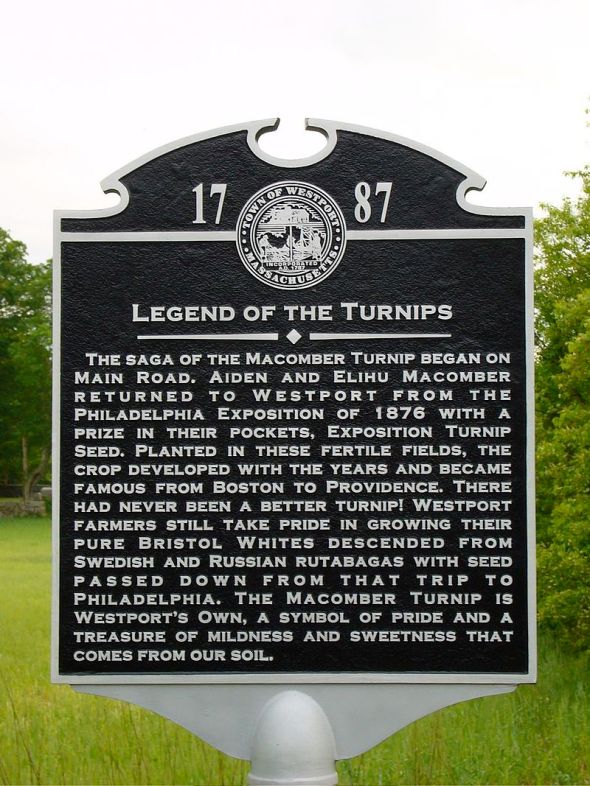

Posted: May 8, 2024 Filed under: medieval studies, New England, rhode island Leave a commentsent by our Rhode Island correspondent.

Thad Cochran

Posted: December 17, 2023 Filed under: America Since 1945, Kennedy-Nixon, Mississippi, New England Leave a comment

Poking around the Edward Kennedy oral history project at The Miller Center I find this interview with former Mississippi senator Thad Cochran.

Cochran was a young Naval officer in Newport when he happened to get an invitation to the Kennedy compound from an Ole Miss coed friend who was working as cook there:

Heininger

What were your impressions of [Ted Kennedy] that very first time you met him in Hyannis Port?

Cochran

Very casual, easy to be with, approachable, good sense of humor, big appetite. He liked chocolate-chip cookies, I know that. He stood there and ate a whole fistful of chocolate-chip cookies, which my friend would make on request. She was apparently good at that.

As a young naval officer here’s what Cochran thought of the buildup to Vietnam:

But then the Vietnam thing came along, and it started getting worse and worse. I didn’t get called back in the Navy to serve in Vietnam, but I was teaching one summer in Newport when the Gulf of Tonkin incident occurred. Just trying to figure that one out and reading about what had happened and looking at a couple of television things of the bombing of the port at—where was it, Haiphong, something like that? I thought, I cannot believe this. What the heck is President Johnson thinking? What is he doing? How are we going to back away from that now, responding to this attack against a merchant ship, as I recall?

Anyway, I began worrying about it. I think, in one of my classes, I even asked the students, the officer candidates about to be officers in the U.S. Navy, would they like to go over to Vietnam and fight over this? Would they like to escalate this another notch? Is there something in our national interest? Of course they were scared to death of it. They didn’t want to say anything, but I think I expressed my view kind of gratuitously, and then later I worried that I was going to get reported for being a belligerent, anti-American Naval officer. I really became angry and frustrated and upset with the way this thing was going, and it just got worse, as everybody knows.

How did he end up in elected office?:

So then I went back to practicing law and just working and enjoying it. I forgot about politics, and then our Congressman unexpectedly announced that he was not going to seek re-election. His wife had some malady, some illness, and the truth was, he was just tired of being up here and wanted to come home. It took everybody by surprise. I’m minding my own business again one day at the house and the phone rings, and it’s the local Young Republican county chairman, Mike Allred, who called and said,

You know, you may laugh but I’m going to ask you a serious question. This is serious. Have you thought about running for Congress to take Charlie Griffin’s place?And I said,Well,and I laughed because I said,You know, I have thought about it. I was surprised to hear that he wasn’t going to run, but I’ve thought about it, and I’ve decided that I’m not interested in running. I’ve got too much family obligation, financial opportunities, the law firm,etc.I think Congressmen were making about $35,000 a year or something like that. There was a rumor it might go up to $40,000. I thought, Well, I have a wife and two young children, and there’s no way in the world I can manage all that, and in Washington, traveling back and forth, etc. But it would be interesting. It’s going to be wide open. It was an interesting political situation. Then he said,

Well, let me ask you this: have you thought about running as a Republican?I laughed again and I said,No, I surely haven’t thought about that.I was just thinking about the context of running as a Democrat, and so I was still thinking of myself as a Democrat in ’72.He said,

Would you meet with the state finance chairman? We’ve been talking about who would be a good candidate for us to get behind and push, and we want to talk to you about it. We really think there’s an opportunity here for you and for our partyand all this. I said,Well, Mike, I’ll be glad to meet and talk to you all, but look, don’t be encouraged that I’m going to do it. But I’m happy to listen to whatever you say. I’d like to know what you all are doing, as a matter of curiosity, how you got off under this and who your prospects are and that kind of thing. I’d like to know that.So I met with them, and they started talking about the fact that they would clear the field. There would not be a chance for anybody to win the nomination if I said I would run. I thought, Golly, you all are really serious and think a lot of your own power. I started thinking about it some more, and I asked my wife what she would think about being married to a United States Congressman, and she said,

I don’t know, which one?[laughs] And that is a true story. I said,Hello. Me.Anyway, a lot of people had that reaction:

What? Are you seriously thinking about this?But everybody that I asked—I started just asking family and close friends, law partners; I just bounced it off of them—I said,What’s your reaction that the Republicans are going to talk to me about running for Congress?I was just amazed at how excited most people got over the idea that I might run for Congress and run as a Republican. That’s unique, and they wouldn’t have thought it because they knew I was not a typical Republican. The whole thing worked out, and I did run, and I did win.

That was ’72. Interesting dynamic in Mississippi that year:

Knott

Were you helped by the fact that [George] McGovern was running as the Democratic nominee that year?Cochran

Yes, indeed. There was no doubt about it. I was also helped by the fact that some of the African-American activists in the district were out to prove to the Democrats that they couldn’t win elections without their support. Charles Evers was one of the most outspoken leaders and had that view. He was the mayor of Fayette, Mississippi, and that was in my Congressional district. He recruited a young minister from Vicksburg, which was the hometown of the Democratic nominee, to run as an Independent, and he ended up getting about 10,000 votes, just enough to deny the Democrat a majority. He had 46,000 or something like that, and I ended up with 48,000 or whatever. I’ve forgotten exactly what the numbers were. The Independent got the rest.

So the whole point was, I was elected, in part—I had to get what I got, and a lot of people who voted for me were Democrats, and some were African Americans who were friends and who thought I would be fair and be a new, fresh face in politics for our state and not be tied to any previous political decisions. I’d be free to vote like I thought I should in the interest of this district. It was about 38 percent black in population, maybe 40 percent, and not only did I win that, but then the challenge was to get re-elected after you’ve made everybody in the Democratic hierarchy mad. I knew they were going to come out with all guns blazing, and they did, but they couldn’t get a candidate. They couldn’t recruit a good candidate. They finally got a candidate but—

Knott

Seventy-four was a rough year for Republicans.

Cochran

It was and, of course, Republicans were getting beat right and left. So when we came back up here to organize after that election in ’74, there weren’t enough Republicans to count. But I was one of them who was here and who was back. Senator Lott, he and I both made it back okay. He was from a more-Republican area: fewer blacks and more supportive of traditional Republican issues.

His opinion on the state of affairs:

Serving in the Senate has gotten to be almost a contact sport, and that’s regrettable, in my view. I would like for it to be more like it was when I first came to the Senate. There was partisanship, right enough, and if you were in the majority, you got to be chairman of all the subcommittees, and none of the Republicans, in my first two years, were chairmen of anything, but that’s fine. That’s the way the House is operated. I’d seen that in the House, and that’s okay. Everybody understands it. But since it’s become so competitive—and the House has too—things are more sharply divided along partisan lines than they ever have been in my memory, and I think the process has suffered. The legislative work product has deteriorated to the point that legislation tends to serve the political interests of one party or the other, and that’s not the way it should be.

Who does he blame?:

I’ve been disappointed in the partisanship that has deteriorated to the point of pure partisanship in court selections, in my opinion, in the last few years, and [Ted Kennedy’s] been a part of that. I’m not fussing at him or complaining about it. It’s just something that has evolved, but all the Democrats seem to line up in unison to badger and embarrass and beat up Republican nominees for the Supreme Court in particular. But it’s extended to other courts, the court of appeals. They all lined up and went after Charles Pickering from my state unfairly, unjustly, without any real reason why he shouldn’t be confirmed to serve on the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. He had run against me when I ran for the Senate, Pickering had. I defeated him in the Republican primary in 1978. So we haven’t been political allies, but I could see through a lot of the things.

I have a close personal friendship with Pat Leahy and Joe Biden, and I could probably name a few others. I’ve really been aggravated with them all for that reason, and I hope that we’ll see some modification of behavior patterns in the Judiciary Committee. Occasionally they’ll help me with somebody. I’m going to be presenting a candidate for a district court judgeship this afternoon in the committee, and yesterday Pat came up, put his arm around me, and said,

I know you’re for this fellow, [Leslie] Southwick, who is going to be before the committee, and I want you to know you can count on me.Well, I’m glad to hear that.There’s nothing wrong with him. I mean, he’s a totally wonderful person in every way. He’ll be a wonderful district judge.I’m not saying that they make a habit of it, but they’ve picked out some really fine, outstanding people to go after here recently, and there are probably going to be others down the line that they’ll do that. Ted’s part of that, and I think all the Democrats do it. I think that’s unfortunate.

Knott

Are they responding to interest group pressure? Is that your assessment?

Cochran

I think that has something to do with it, but I’m not going to suggest what the motives are or why they’re doing it, but it’s just a fact. It’s pure partisan politics, and it’s brutal, mean-spirited, and I don’t like it.

Heininger

What do you attribute the change to?

Cochran

I don’t know. I guess one reason is we’re so closely divided now. You know, just a few states can swing control of the Senate from one party to the next, and we have been such a closely divided Senate now for the last ten years or so. Everybody understands the power that comes with being in the majority, and I’m sure both parties have taken advantage of the situation and have maybe been unfair in the treatment of members of the minority party, denying them privileges and keeping their amendments from being brought up or trying to manage the schedule to the benefit of one side or the other.

Cochran died in 2019. In the Senate he used Jefferson Davis’s desk.

Boston as Mecca and Medina

Posted: September 30, 2023 Filed under: Boston, Kennedy-Nixon, New England Leave a commentGlobe reporter and editor Martin Nolan, towards the end of his interview for the Miller Center on the life and career of Edward “Ted” Kennedy:

Knott

How would you explain to somebody reading this transcript, hopefully 100 years from now or so—that’s our goal here, to create an historical record that will last. How would you explain the hold of the Kennedys, particularly on the people in Massachusetts, that would allow somebody like Senator Kennedy to have a 44-year career in the United States Senate, as we speak today?

Nolan

In Massachusetts we do indeed revere the past. There’s nothing wrong with that. In the 1970s, during the great energy crisis, a guy I knew, Fred Dutton, was the lobbyist for the Royal Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He had been another guy doing well by doing good. He came to work for Jack Kennedy in the White House as Assistant Secretary of State and worked for Bobby Kennedy and McGovern and all this. He landed on his Guccis with this job. He says,

Look, there’s this Minister of Petroleum, Sheikh [Zaki] Yamani.Do you remember Sheikh Yamani? He says,He’s coming to town and I’d like him just to get a flavor. Would you like to get an exclusive?Yes, geez, he was the biggest guy going.He takes me to lunch at the Watergate Hotel, just the two of us, wonderful, because I kind of knew the subject. Oil is very important for furnaces in New England. He’s talking about OPEC [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] and stuff like that. He’s giving me a big Churchill Havana cigar, sitting there like he’s got all day, and he said,

You know, Mr. Nolan, we have oil running under the sands of Saudi Arabia. We have a lot of oil, but it is a finite resource. We all know that,he says.But we have Mecca and Medina and we will never run out of Mecca and Medina.I probably put it in at the bottom, if I put it in at all, because it didn’t relate to the price of oil.But that’s what we have in Boston, Massachusetts. Yes, we’ve got hospitals and universities and all that, but we have history, and you never run out of history. That is the great contribution Jack Kennedy made with Profiles in Courage. He knew that the history he learned just by walking around—I used to take the Harvard fellows on a tour, my little walking political tour. You don’t have to go far; it’s all around the State House. I would show them the statue of William Lloyd Garrison, the liberator. Jack Kennedy had remembered the statue and sent a guy to take the—in his last speech in America he said he wanted to have this before he went on to see Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna. I was covering it at the Commonwealth Armory. It was a great time and he said,

I take with me an inscription on a statue of a distinguished and vigorous New Englander, William Lloyd Garrison: ‘I am in earnest….I will not retreat a single inch and I will be heard.’Another time, Kennedy was walking along—He’s got this apartment over there on Bowdoin Street. This is where Jack Kennedy’s mattress was, I mean, that’s his voting address. Right there at about Spruce Street, James Michael Curley, for the 300th anniversary of the founding of Boston, has this wonderful relief. It’s an Italian sculptor and a Yankee architect and an Irish mayor, and the words are from John Winthrop:

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us.Reagan took it, as you know. In fact, we were flying in over Dorchester Bay. The Reagan people are smart. You have the local guy go in with the candidate. He said,

Now what is that?I said,Well that’s actually Dorchester Bay, but that’s where the Arbella lay anchored when John Winthrop, you know, the guy with the ‘city on a hill’? Kennedy used that in his speech to the Massachusetts Legislature long before you got it.He said,No kidding, really?I said,January 9, 1961, Governor, ‘For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us.’Kennedy took that and thought that sentiment should be spread to the Massachusetts Legislature. What he meant was, please don’t steal, or don’t steal as much as you have been doing, and they all thought, Ah, isn’t it great that Jack Kennedy was elected? The message went over their heads.You see all that sense of history just living, going back to Honey Fitz and Curley, and these people all had it. He is the essence of a Boston politician. They’re all rooted and it’s a phenomenal thing to have this. We have the myth, Damon and Pythias. There was not a third guy in there, right? Just think of what Edith Hamilton could have done with this, you know? You’ve got one martyred guy and then another martyred guy, and then the third guy turns out to be the greatest United States Senator in history by a measuring of accomplishment, involvement, whatever—what Adam Clymer’s book said. It’s pretty much every issue except the environment, which is not a New England issue, in a way. But there’s no issue that it does not affect. I mean, civil rights, labor law, education, health—what are we missing? Foreign policy? Vietnam.

What a remarkable thing. There’s nothing like it in American history certainly and I’m unaware of another family like that—the primogeniture. One guy dies in the war, the other guy is kind of diffident and not too keen on running, but he runs. He gets killed and then the brother, not too keen on politics, but he runs and he gets killed, and then the guy who’s really good at politics survives.

Lizzie (2018)

Posted: April 13, 2022 Filed under: crazy, murders, New England Leave a commentWe were talking about ax* murders after a visit to the Villisca ax murder house in Villisca, Iowa. Someone asked me if I’d ever been to the Lizzie Borden house in Fall River, MA. I had to sheepishly admit I never had. Massachusetts is blessed with more cultural and natural attractions than southwestern Iowa, thus we didn’t have to fixate on one century-plus-old ax murder site, so I never made the pilgrimage.

Uncle-in-law Tony mentioned that there was a movie starring Kristen Stewart and Chloë Whatsername about the case. I was stunned, how could such a movie have passed me by?

Back home, I watched it immediately. I wouldn’t exactly race to see it, it’s a bit stylish and slow at times, but Kristen Stewart and Chloë Sevigny are fantastic in it. These are incredible actresses doing stunning work. The version of the case presented in the film (spoiler) seems somewhat plausible to me as a non-student: that Lizzie (Sevigny) and Irish housemaid Bridget Sullivan (Stewart) had a sexual relationship. Lizzie took the lead on the murdering, and Sullivan covered for her.

In Popular Crime, Bill James posits that Lizzie was innocent, or at least that she shouldn’t’ve been convicted, citing some timeline discrepancies. Lizzie had no blood splatter on her clothes. James dismisses the idea (presented vividly in the film) that she might’ve done the murders in the nude.

Again, this seems to be virtually impossible. First, for a Victorian Sunday school teacher, the idea of running around an occupied house naked in the middle of the day is almost more inconceivable than committing a couple of hatchet murders. Second, the only running water in the house was a spigot in the basement. If she had committed the murders in the nude, it is likely that there would have been bloody footprints leading to the basement – and there is no time to have cleaned them up.

I dunno, I think Victorians – should that term even apply in the USA? – were weirder and nudier than we may realize. And maybe there wouldn’t be bloody footprints, I’m no expert on blood splatterings and footprint cleanings. In my own life I’ve found you can clean up even a big mess in a hurry if you’re motivated. Even James concedes that it does seem Lizzie burned a dress in the days after the murders. This doesn’t worry him though and he refuses to charge it against Lizzie. He proposes no alternate solution to the case.

The famous rhyme is pretty strong propaganda. If you’re ever accused of a notorious murder, you’d be wise to hire the local jump rope kids to immediately put out a rhyme blaming one of the other suspects. It may have been too late in Lizzie’s case, but here’s what I might’ve tried:

A random peddler walking by,

Chopped the Bordens, don’t know why

or

Johnny Morse killed his brother-in-law,

Used an ax instead of a saw.

When he saw what he could do

He killed his brother-in-law’s wife too.

These are not as catchy. On the second one for instance you may need to add a footnote that Morse was brother to Andrew Borden’s deceased first wife, Lizzie’s mom.

True crime has never been a passion of mine, but I can see the appeal. You’re dealing with a certain set of known information which you can weight as you see fit, balanced with aspects that are epistemically (?) unknowable. In that way it’s a puzzle not unlike handicapping a horse race.

I’m reading Bill James (with Rachel McCarthy James) The Man from the Train now, centered on the Villisca murders. It’s very compelling. James is such an appealing writer, and he’s on to a good one here. One way or another, there was a staggering number of entire families murdered with an ax between 1890 and 1912. Something like 14-25 events with 59-94 victims. That is wild. In these ax murders, by the way, we’re talking about the blunt end of the ax. Lizzie or whoever did the Fall River murders as I understand it used the sharp side.

The people I spoke with in Villisca seemed more focused on possible local solutions, the Kelly and Jones theories in particular. Maybe they don’t want to admit that their crime, which did make their town famous, was just part of a horrible series, rather than a special and unique case. The Man From The Train put me in mind of the book Wisconsin Death Trip, which is nothing more than a compiling of psycho events from Wisconsin newspapers from about 1890-1900, awful suicides, burnings, poisonings, fits of insanity, etc., plus a collection of eerie photographs from that time and place. The thesis is that the US Midwest was having something like a collective mental breakdown during the late 19th century.

Anyway, if you like creepy lesbian psychodramas, Lizzie might be for you! The sound design is good on the creaks of an old wooden house.

* I’m using the spelling ax that is used on the Villisca house signage, although axe is more common in the USA

Evacuation Day

Posted: March 17, 2022 Filed under: Boston, Ireland, Irish traditional music, New England Leave a commentToday is Evacuation Day in Boston, the day the British finally quit the city, giving up on the siege. Conveniently, it falls on Saint Patrick’s Day, so it’s Brits Out all around.

“Had Sir William Howe fortified the hills round Boston, he could not have been disgracefully driven from it,” wrote his replacement Sir Henry Clinton.

I thought this was interesting in this plaguey time:

Once the British fleet sailed away, the Americans moved to reclaim Boston and Charlestown. At first, they thought that the British were still on Bunker Hill, but it turned out that the British had left dummies in place. Due to the risk of smallpox, at first only men picked for their prior exposure to the disease entered Boston under the command of Artemas Ward. More of the colonial army entered on March 20, 1776, once the risk of disease was judged low.

How about Howard Pyle’s painting of Bunker Hill? (I can hear a Bostonian voice correcting me: “you mean Breed’s Hill?)

Can’t have been a fun time for British troops, half of whom were probably Irish recruits anyway. And what of the Dublin born Crean Brush, who met a sad fate for his Loyalism?

While imprisoned in Boston, Brush was denied privileges. He consoled himself with alcohol.

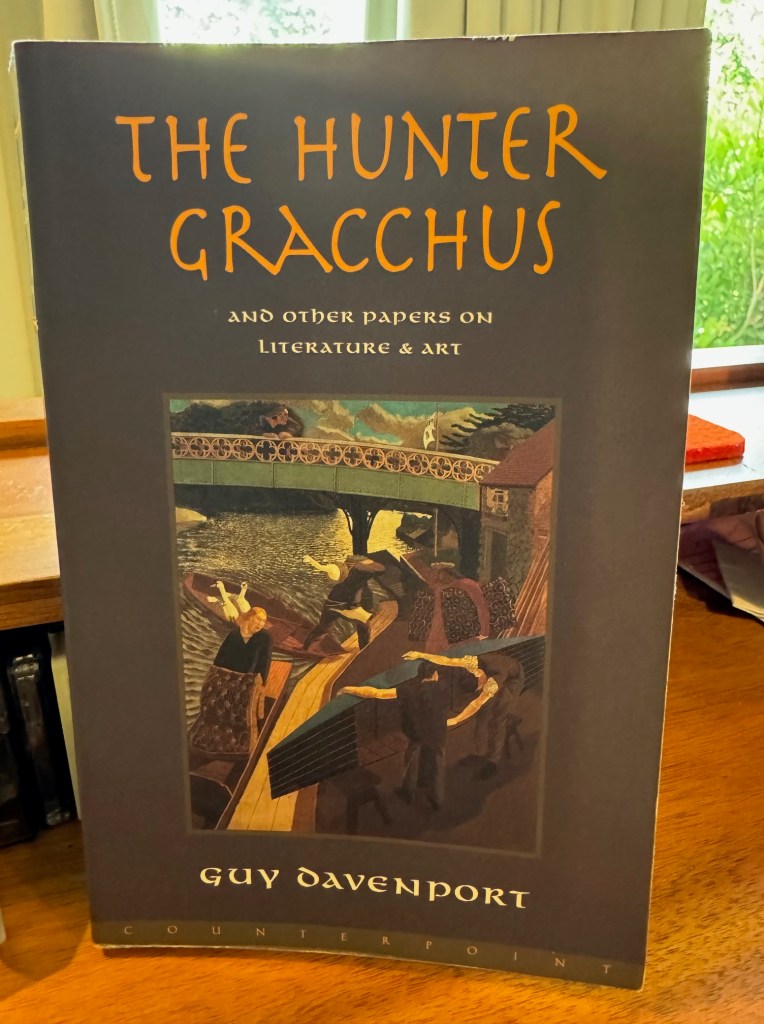

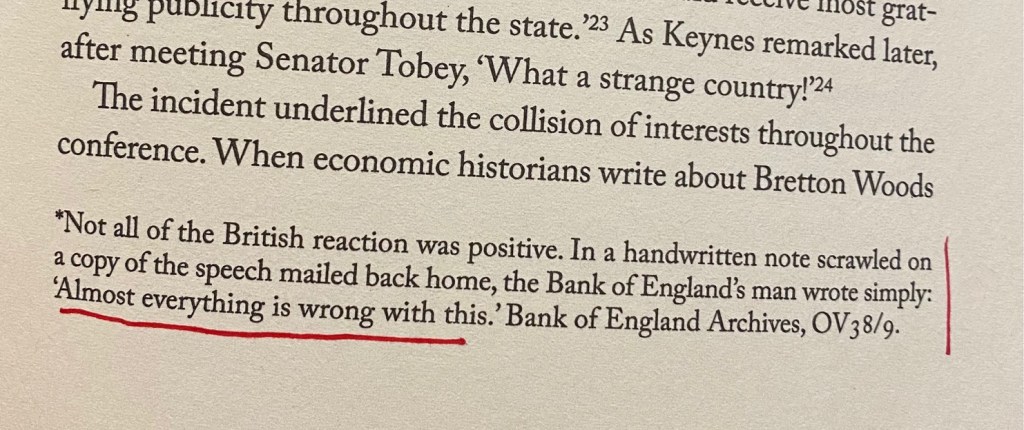

Bretton Woods Is No Mystery and The Nixon Shock

Posted: March 7, 2021 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, money, New England Leave a commentBreaking the Breton Woods agreements, the American president said that the dollar would have no reference to reality, and that its value would henceforth be decided by an act of language, not by correspondence to a standard or to an economic referent.

That’s from The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, by Italian communist Franco “Bifo” Berardi, published by semiotext(e). Full of interesting ideas.

Everywhere I turn these days, from the new Adam Curtis documentary to the Bitcoin-heads on Twitter, I hear about Sunday, August 15, 1971. On that evening, Richard Nixon, conferring with his advisors in a weird weekend at Camp David, went on TV and announced he was taking the US dollar off the gold standard. Nixon ended the “Bretton Woods system.”

Always had an interest in the Bretton Woods system. Worked out at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods*, New Hampshire. My dad and I went cross-country skiing up there.

The hotel shut up for winter had a spooky, imposing quality.

President Franklin Roosevelt proposed the conference site, the Mount Washington Hotel, as a ploy (successful, as it turned out) to win over a likely opponent of the pact, New Hampshire senator Charles Tobey.

That’s from Michael A. Martorelli’s review of Benn Steil’s book about the conference, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order.

The conference happened in July 1944. The Allied forces were stalled in the bocage of Normandy. But leadership was planning for the postwar order. John Maynard Keynes, who’d studied the disaster of the last postwar peace, was trying to avoid the same mistakes while attempting to save the dignity of the UK. Keynes suggested the world switch to a global currency called Bancor. The US, represented by Harry Dexter White, dominant, had the strong position. The US proposed to leave the US dollar, pegged to gold, as the world’s reserve currency.

Deeply indebted to the United States after the long, costly ordeal of World War II, the United Kingdom inevitably lost the battle. To secure one key victory, however, White had to resort to stealth. In the waning hours of the conference, he and his assistants replaced the phrase “gold” with “gold and US dollars” in the agreement, thereby enshrining the US currency as the international medium of exchange. Keynes confessed that he did not read the final version of the document he signed.

You think there aren’t thrills in a book about a 1944 economic conference whose results have been overturned? Wrong:

In one noteworthy coup, [Steil] disproves Keynes biographer Robert Skidelsky’s claim that Keynes was assigned Room 129 in the Mount Washington Hotel.

The summit does sound exciting. The Soviets brought a bunch of female “typists” to seduce everyone.

One committee of delegates took a 15-minute recess in the bar each night at 1:30 to watch the “titillating gyrations of Conchita the Peruvian Bombshell.” Afterward, reinvigorated, they would negotiate for another hour or so. The long arguments left White increasingly short-tempered on less than five hours of sleep a night. Keynes, already weakened by the heart disease that would kill him within two years, was soon holding court from his bed, tended (and guarded) by Lydia, his eccentric Russian ballerina wife. At one point, a rumor spread that he was near death; when he then appeared at dinner, the delegates spontaneously stood and sang “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.”

from a different review of a different book about the conference:

I’ve taken a look at both Steil and Conway’s books. The Summit by Conway is more fun and easy to read, and focuses on the wild details – what he calls the “noises off” stuff – from the conference. The drunken songs, the parody newspaper about the “International Ballyhoo Fun,” the pleasure delegates from wartorn countries took in plates of “chicken Maryland” and bowls of ice cream, the South Africans playing golf once it was clear gold wouldn’t be replaced by silver, the results of the Soviet vs USA volleyball game (USSR won), that’s in Conway.

The details of the conference are interesting, but the outcome was inevitable. The US was the last power standing as World War II ended. The UK was in our debt (literally). What we ended up with was the system we devised: the dollar as default world currency.

The true significance of the conference was noted by Keynes in a speech at the farewell dinner:

We have shown that a concourse of 44 nations are actually able to work together at a constructive task in amity and unbroken concord. Few believed it possible. If we can continue in a larger task as we have begun in this limited task, there is hope for the world.

If you read one review of one book about the conference, read James Grant’s review of Steil in the Wall Street J (behind a paywall, they’re no fools about money at the WSJ):

Gold figures largely in these pages. The ancient metal was deeply rooted in the psyche of Keynes’s contemporaries, including that of Lt. Col. Sir Thomas Moore, a British Conservative member of Parliament. In parliamentary debate, Sir Thomas said that he had “the impression, not being an economist, that currency had to be tied to or based on something; whether it was gold, or marbles, or shrimps, did not seem to matter very much, except that as marbles are easy to make, and shrimps are easy to catch, gold for many reasons possessed a more stable quality.” For the soundest doctrine expressed in the fewest words, Sir Thomas was hard to beat.

Grant, if you can’t read it, isn’t too boosterish on the Bretton Woods system:

Rare among nations, America pays its overseas debts in money that it alone may lawfully print. Naturally, being human, we Americans have printed to excess. Not since 1975 has the United States exported more goods and services than it has imported. There is no institutional check to square up accounts. We buy Chinese merchandise with dollars. The Chinese, in turn, invest those dollars in U.S. government securities (the better to suppress the value of the Chinese currency). It’s as if the money never left the 50 states. In possession of the “reserve currency” franchise—White’s dream fulfilled—America has become the world’s leading debtor nation. At Bretton Woods, it was the world’s top creditor.

Mentioned the Nixon Shock to a bud who works at a hedge fund, and he put me on to WTF Happened in 1971, which takes a darker view. Love the idea that this is the moment everything went wrong and reality broke, but I’m not convinced. What about the Triffin dilemma? Was Nixon changing reality, or acknowledging it?

Consider how things worked before Bretton Woods. Both Conway and Stiel note that FDR would dictate the dollar price of gold from bed in the morning, once raising the price by twenty-one cents because that was a lucky number. This was more “real”?

A crazy element of the conference is that the leader of the US delegation, Harry Dexter White, was communicating with the Soviets. To what extent he was a traitor, a spy, vs kind of backchannel with our wartime ally is unclear. But declassified transcripts make clear he was a Soviet asset known at “Jurist” or “Richard.” That’s if you trust our own NSA. Who knows?

White testified in front of HUAC that he was not a Communist, then had a heart attack. He went to his home in New Hampshire and died four days later.

Is it possible White sabotaged the US team in the Bretton Woods volleyball game? To provide a propaganda win for his Soviet masters? The Russians got a lot of concessions at Bretton Woods to induce them to sign on to the agreements. But I don’t see in Steil or Conway any case that White’s possible connection helped them. Conway is a skeptic on the spy stuff, suggesting that yes, it looks fishy, but it’s impossible to prove White “betrayed his country.”

One person who would’ve known White had been a spy? President Richard Nixon.

Following Alger Hiss’s perjury conviction in 1950, Representative Richard M. Nixon revealed a handwritten memo of White’s given to him by Chambers, apparently showing that White had passed classified information for transmission to the Soviets. Yet his guilt would only be firmly established after publication of Soviet intelligence cables in the late 1990s.

The IMF and World Bank linger as Bretton Woods legacies. Conway in his epilogue notes how even after the demise of the Bretton Woods system, the IMF still imposes the “Washington Consensus” on the developing world in return for loans. Maybe someone should activate the Coconut Clause:

Conway also notes that after the demise of the system, US and British banks became more profitable.

In the United States, by the turn of the millennium banks now accounted for around 8 per cent of the country’s total economic output – more than double their zie when the Bretton Woods system ended… Until 1970, an investor in a UK bank could expect to make about 7 per cent a year on his investment. After 1970, the return on equity roughly trebled to 20 per cent, a figure maintained without a break until the financial crisis of 2008.

There is no single, simple explanation for this astonishing rise of the financial sector; however, there is no doubt that one important element is the sudden change in the international monetary architecture following the collapse of Bretton Woods. Almost immediately after the demise of Keynes and White’s system in the early 1970s, every single measure of the size, profitability, and leverage of the banking industry has begun to increase at unprecedented rates.

The big banks in the USA tried to stop Bretton Woods at the time,

After the Bretton Woods conference, the countries involved had to sell it to a confused public. One method the USA used was a pamphlet called Bretton Woods Is No Mystery, illustrated by the New Yorker cartoonist Syd Hoff. I’m on the trail of a copy, I can only find a few images online.

Heartbreaking to hear the names bandied about for the world currency, and think what might’ve been. From Conway:

among the suggestions were Fint, Proudof, Unibanks, Bit, Pondol, and Keynes’ favorite, Orb. Months later, Keynes sent round a note to his Treasury colleagues asking: “Do you think it is any use to try unicorn on Harry?”

What do you guys think will be the world’s reserve currency in 2031? Dogecoin?

*an archaic name for what’s now part of Carroll, New Hampshire.

Carlyle and Alcott have breakfast

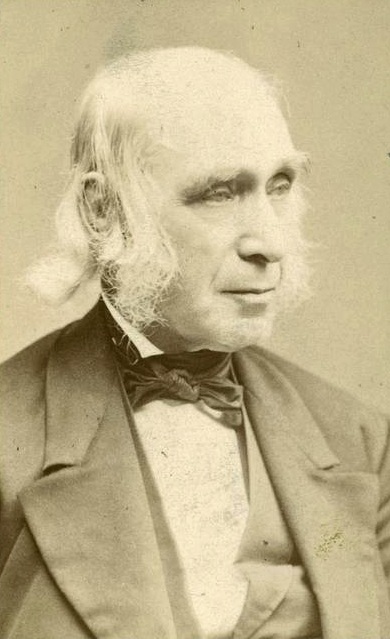

Posted: February 2, 2021 Filed under: food, New England 2 CommentsThis is Amos Alcott, Louisa May’s father, fictionalized as Bob Odenkirk in the latest Little Women film:

from The Flowering of New England by Van Wyck Brooks, a vivid read. Imagine this man chowing down on strawberry potatoes:

change / the same

Posted: January 27, 2021 Filed under: America Since 1945, business, New England 1 Comment

That’s Van Wyck Brooks, going off in The Flowering of New England about the generation of the 1840s.

Latitudes and attitudes

Posted: January 8, 2021 Filed under: Boston, Ireland, New England Leave a commentsomehow this map of Dublin swam into my ken, maybe on Twitter or something. I was struck by how the shape of Dublin’s harbor is similar to that of Boston’s. I’ve had three chances to visit Dublin, and I never put this together:

Tried to get those at roughly the same scale, with help from Zaia Design’s Two Maps:

Both east-facing harbors. Dublin’s a little smoother, makes sense, it’s older*, more time to smooth it down.

Dalkey, in vibe, is kind of like Hingham, too. Is Winthrop like Howth? I don’t know enough about the vibes of either Winthrop or Howth to report. There was a girl from Winthrop at a nerd camp I attended one summer. I remember her talking about the difficulty of going back and forth to the school she attended in Cambridge, but that’s about it, it’s neither here nor there when it comes to comparative geography, although maybe there was some girl in Howth at the exact same time with the exact same problem.

If there’s a Dublin equivalent of Hull, I bet that’s interesting, but it looks like in the south portion of Dublin harbor there are no crooked fingers of that nature.

Boston is at a latitude about 42.36 N. Dublin’s at 53,74, farther north, even north of Montreal (45.50) and even north of St. Johns, Newfoundland (47.56). The reason why Dublin’s climate is more temperate than that of Montreal has to do with, I believe, the gulf stream bringing warm air across the Atlantic. In very southern Ireland I visited a town that had some palm trees, I forget which town that was, it was over twenty years ago. I could probably find out but I’m not going to bother.

As for latitudes, Los Angeles is at 34.05, comparable to Baghdad (33.31). You might think weather-wise it might be aligned with Mediterranean cities, Barcelona for example, but Barca is further north (41.38). Paris is at 48.85 N. Tokyo is a close latitude cousin to LA, at 35.68 N. Interestingly, in the southern hemisphere, several major cities with attractive weather are in a similar range:

Melbourne: 37.85 S

Sydney: 33.86 S

Cape Town: 33.92 S

Buenos Aires 34.06 S.

In that same band N:

San Francisco: 37 N

Athens: 37 N

Las Vegas: 36 N

Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto: 35 N

“Somebody out there must’ve compared cities by latitude before me,” I thought, and sure enough, here is “174 World Cities by latitude: Things Line Up In Surprising Ways” from a website about the business of travel.

Crazy that Chicago and Barcelona are at the same latitude. Both great, but quite different vibes (and climates. And food tastes).

* kidding?

April 19

Posted: April 19, 2020 Filed under: America, Boston, New England Leave a comment

We can never let a Patriots’ Day go by without reflecting on the events of April 19, 1775. How did this happen?

The people of countryside Massachusetts at that time were probably the freest and the least taxed people in the British Empire. What were they so mad about?

From my hometown of Needham, MA, almost every able bodied man went out. What motivated people that morning to grab guns and shoot at their own army?

Lately I’ve been reading Rick Atkinson’s book on the first years of the American Revolution. It’s interesting that Atkinson titled his book this, because as he himself notes:

Popular lore later credited him with a stirring battle cry – “The British are coming!” – but a witness quoted him as warning, more prosaically, “the regulars are coming out.”

The word would’ve gotten out anyway, because of information sent by light in binary code: one if by land, two if by sea. (it was two).

Atkinson does a great job of laying out how tensions and feelings and fears and resentments escalated to this point. George III and his Prime Minister Lord North (they’d grown up together, it’s possible they were half-brothers) miscalculated, misunderstood, overreacted.

North held a constituency in Banbury with fewer than two dozen eligible voters, who routinely reelected him after being plied with punch and cheese, and who were then rewarded with a haunch of venison.

The image of a stern father disciplining a disobedient child seemed to guide George III/North government thinking. Violently putting down rebellions was nothing new, even within the island of Britain. Crushing Scottish revolt had been a big part of George III’s uncle’s career, for example.

From the British side, the disobedience did seem pretty flagrant, the Boston Tea Party being a particularly outrageous and inciting example, from a city known to be full of criminals and assholes. The London government responded with the “Coercive Acts.”

With this disobedient child, the punishment didn’t go over well. The mood had gotten very, very tense in Boston when the April 19 expedition was launched.

Everything about it went wrong. Everybody was late, troops were reorganized under new commanders. Orders were screwed up, the mission was unclear. It was a show of force? A search and destroy? Both? The experience for the soldiers in on it was awful: started out cold and wet, ended up lucky if you were alive and unmangled.

What the Lexington militia was up to when they formed up opposite the arriving Redcoats is unclear. Did they intend to have a battle? Doesn’t seem like it, why would they line up in the middle of a field? There’d already been an alarm, and then a weird break where a lot of the guys went to the next door tavern and had a few.

Were they intending just kind of an armed protest and demonstration (as is common in the United States to this day)?

A lot of the guys in the Massachusetts militias had fought alongside the British army in the wars against the French and Indians. Captain Parker of Lexington had been at Louisburg and Quebec. How much was old simmering resentment of the colonial experience serving with professional British military officers a part of all this?

One way or another, a shot went off, and then it got out of hand very fast. When it was over eight Lexington guys were dead.

The painting above is by William Barnes Wollen, he painted it in 1910. Wollen was a painter of military and battle scenes. He’d been in South Africa during the Boer War, so maybe he knew what an invading army getting shot at by locals was like.

Amos Doolittle was on the scene a few days after the events, interviewed participants, walked the grounds, and rendered the scene like this.

But Doolittle had propaganda motives.

After the massacre at Lexington the British got back into formation and kept moving.

They ran into another fight at Concord Bridge.

Information and misinformation and rumor became a part of the day. The story spread that the British were burning Concord, maybe murdering people.

By now minutemen from all over were blasting away. It must’ve been horrific. Atkinson tells us that the British “Brown Bess” musket fired a lead slug that was nearly .75 of an inch in diameter (compare to, say, a Magnum .45, .45 of an inch).

How would history have been different if the British column had been completely wiped out, like Custer’s last stand? It almost happened. The expedition was saved by the timely arrival of reinforcements with two cannons.

The column avoided an ambush at Harvard Square, but several soldiers died in another gunfight near the future Beech and Elm Streets while three rebels who had built a redoubt at Watson’s Corner were encircled and bayoneted. William Marcy, described as “A simple-minded youth” who thought he was watching a parade, was shot dead while sitting on a wall, cheering.

They were able to get back across the river and into Boston, minus 73 killed, 53 missing, 174 wounded. A bad day in Massachusetts.

This event looms large in the American imagination: the gun-totin’ freedom lovers fighting off the government intrusion. But the more you read about it the more it sounds like just a catastrophe for everyone involved.

Back in Needham the Rev. West reported:

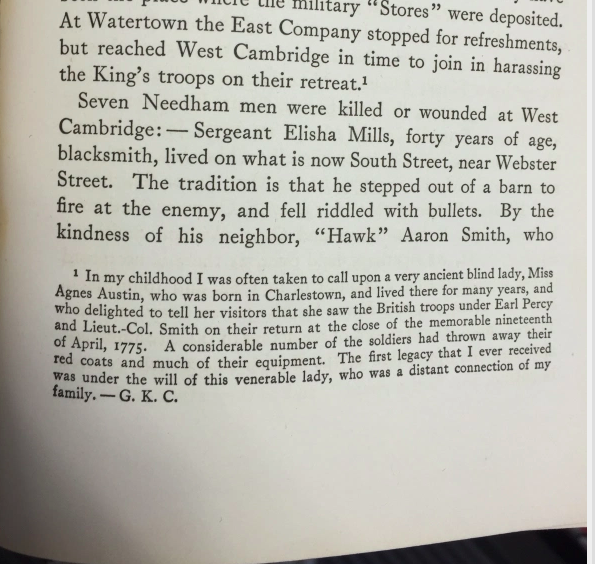

In the evening we had intelligence that several of the Needham inhabitants were among the slain, and in the morning it was confirmed that five had fallen in the action and several others had been wounded. It is remarkable that the five who fell all of them had families, and several of them very numerous families so that there were about forty widows and fatherless children made in consequence of their death. I visited these families immediately, and with a sympathetic sense of their affliction I gave to some the first intelligence they had of the dreadful event, the death of a Husband and a Parent.

The details.

Daniel Vickers

Posted: February 1, 2020 Filed under: history, New England 3 Comments

source

Happened to turn on the TV the other day and Good Will Hunting was on. What a great movie. It’s a superhero movie.

We were right in the scene where Will backs up Ben Affleck and destroys a jerk who’s showing off his education.

One moment in this scene I’ve thought about more than necessary is when Will identifies the jerk (he’s listed as “Clark” on IMDb, played with precision by Scott William Winters) as “a first year grad student.” Given how much Clark knows about history, and his reading list, should we infer that Scott William Winters is a first year grad student in history?

WILL: See the sad thing about a guy like you is in about 50 years you’re gonna start doing some thinking on your own and you’re gonna come up with the fact that there are two certainties in life. One, don’t do that. And two, you dropped a hundred and fifty grand on a fuckin’ education you coulda got for a dollar fifty in late charges at the Public Library.

CLARK: Yeah, but I will have a degree, and you’ll be serving my kids fries at a drive-thru on our way to a skiing trip.

WILL: [smiles] Yeah, maybe. But at least I won’t be unoriginal.

It’s interesting that Clark’s brag is that Will will be “serving my kids fries on their way to a ski trip.” There are no doubt history professors living this way, but I do feel if that were your goal, becoming a grad student in academic history would be a harder way to go than like, business school or something?

Maybe that is part of the point Will is making about what a dope this guy is.

In their exchange, Will cites “Vickers, Work In Essex County.”

Had to look this one up, and boy, did I profit. I learned about Daniel Vickers, who sounds like an amazing man. From a Globe & Mail “I Remember” by Don Lepan:

Dr. Vickers went to Princeton for his PhD. It was there that he began what became his life’s work academically, but he found Princeton itself stiflingly elitist, and escaped as often as he could to Toronto or to New England towns such as Salem or Nantucket, Mass., where he would spend long hours poring over local records.

God that’s beautiful. Can you imagine sitting in Nantucket, poring over the records? (Yes).

This was followed in 2005 by Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail, in which Dr. Vickers challenged the long tradition of treating a young man’s decision to go to sea as an inherently momentous one, and the life of a seafarer as inherently exceptional; again through painstaking archival research, he demonstrated that that most young men who went to sea did so with a sense of inevitability – and that not until the late 19th century did seafaring life begin to seem exceptional. Maritime history was somewhat out of fashion with the general public when the book appeared and it sold less well than its publishers had hoped, but reviews of Dr. Vickers’s work by historians were again extraordinarily enthusiastic; the book was praised as “a masterly work” and “the most original American maritime history ever published.”

As with his first book, Dr. Vickers was aided greatly in his research by his wife, Christine.

Vickers taught at UCSD for awhile, but

the family found the suburban lifestyle and sunny consumerism of San Diego less congenial than the rocky insularity and dour humour of Newfoundland.

If you prefer Newfoundland to San Diego, come sit near me.

Wanted to share that with the Helytimes family. Have a good weekend everyone! I bet the picture of Daniel Vickers here will give you some cheer.

Maine and Texas

Posted: September 17, 2019 Filed under: America Since 1945, food, New England, Texas Leave a comment

This one came up on Succession, a fave show. (Had to look it up because I wondered if they were doing a double joke where the guy was attributing Emerson to Thoreau)

Usually I’ll approach with tentative openness the pastoralist, simpler times, “trad” adjacent arguments of weirdbeards but Thoreau here WAY off. Maine and Texas had TONS to communicate! Who isn’t happy Maine and Texas can check in? (Saying this as a Maine fan whose wife is from Texas, fond of both states and happy for their commerce and exchange). Plus, if Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough, I WANT to hear that, that’s interesting goss!

The “broad flapping American ear” there — a snooty New England/aristocrat attitude we haven’t heard the last of. These guys are the original elites. There’s really two classes in America: Americans, and The People Who Think They’re Better Than Americans. Though they’re a tiny minority the second group wields outside power and influence over the first group. I’m a proud member of the first group though I admit I have second group tendencies due to my youthful indoctrination in the headquarters of these Concord Extremist Radicals, in fact at their head madrassa.

When you hear America assessed by Better Thans / eggheads, wait for the feint toward fatshaming. It’s always in there somewhere. American Better Thans adopted this from Europeans, whom they slavishly ape. It’s a twisted attitude, designed to take blame away from the Better Thans and their friends in the ownership.

As if it’s Americans fault that they’ve been raised associating corn-based treats with love and goodness! Or that corn-fatted meat is the easiest accessed protein on offer! You think that’s more the Americans fault, or the fault of the Better Thans, who manipulate our food system with their only goal creating shareholder value?

Is it the fault of the American that a cold soda is the best cheap pleasure in the hot and dusty interior where they don’t all have Walden Pond as a personal spa?

Thoreau. Guy makes me sick.

In researching this article I learn about Maine-ly Sandwiches, of Houston.

Spinning Ice Disk

Posted: January 25, 2019 Filed under: New England, water Leave a comment

Nothing to worry about, we’re told.

message

Posted: August 5, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, New England, politics Leave a comment

sent by Rhode Island desk

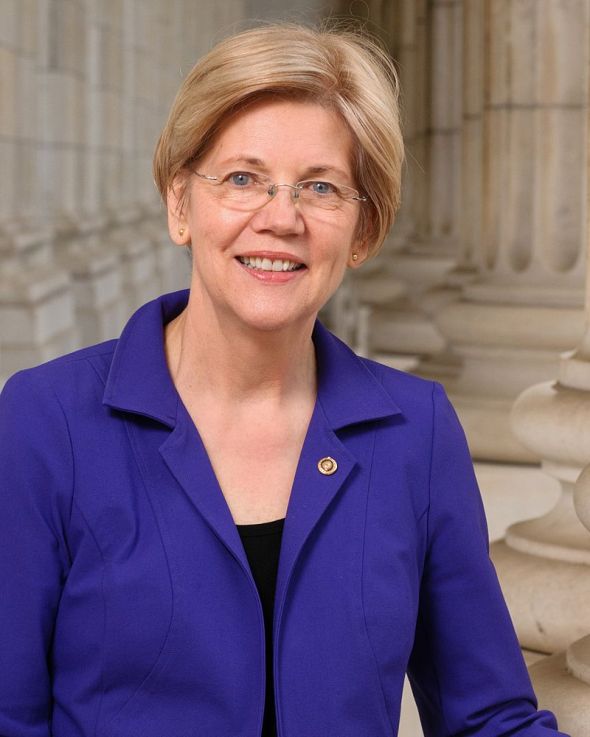

Elizabeth Warren, Pocahontas, and The Pow Wow Chow Cookbook

Posted: December 14, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, Boston, native america, New England, politics, presidents 1 Comment

What is the deal here when Trump calls Elizabeth Warren Pocahontas?

At Helytimes, we like to go back to the source.

Sometime between 1987 and 1992 Elizabeth Warren put down on a faculty directory that she was Native American. Says Snopes:

it is true that while Warren was at U. Penn. Law School she put herself on the “Minority Law Teacher” list as Native American) in the faculty directory of the Association of American Law Schools

This became a story in 2012, when Elizabeth Warren was running for Senate against Scott Brown. In late April of that year, The Boston Herald, a NY Post style tabloid, dug up a 1996 article in the Harvard Crimson by Theresa J. Chung that says this:

Of 71 current Law School professors and assistant professors, 11 are women, five are black, one is Native American and one is Hispanic, said Mike Chmura, spokesperson for the Law School.

Although the conventional wisdom among students and faculty is that the Law School faculty includes no minority women, Chmura said Professor of Law Elizabeth Warren is Native American.

Asked about it, here’s what Elizabeth Warren said:

From there the story kinda spun out of control. It came up in the Senate debate, and there were ads about it on both sides.

A genealogist looked into it, and determined that Warren was 1/32nd Cherokee, or about as Cherokee as Helytimes is West African. But then even that was disputed.

Her inability to name any specific Native American ancestor has kept the story alive, though, as pundits left and right have argued the case. Supporters touted her as part Cherokee after genealogist Christopher Child of the New England Historic Genealogical Society said he’d found a marriage certificate that described her great-great-great-grandmother, who was born in the late 18th century, as a Cherokee. But that story fell apart once people looked at it more closely. The Society, it turned out, was referencing a quote by an amateur genealogist in the March 2006 Buracker & Boraker Family History Research Newsletters about an application for a marriage certificate.

Well, Elizabeth Warren won. Now Scott Brown is Donald Trump’s Ambassador to New Zealand, where he’s doing an amazing job.

source: The Guardian

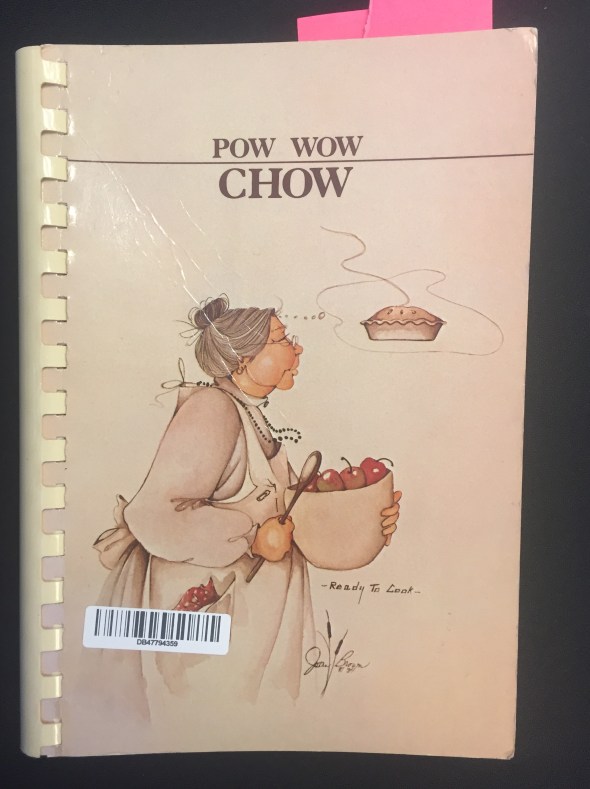

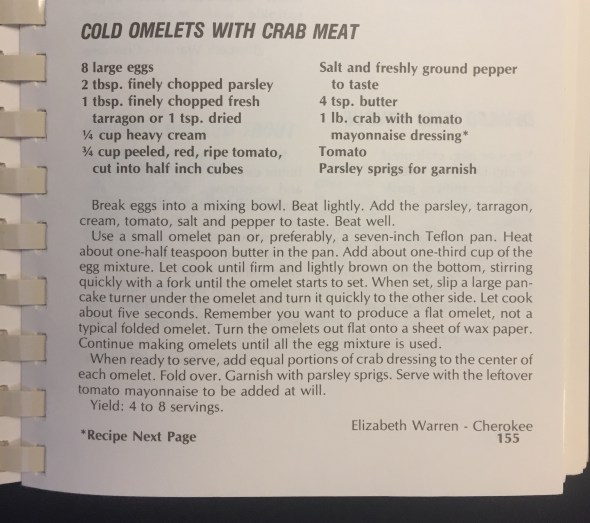

The part of the story that lit me up was this:

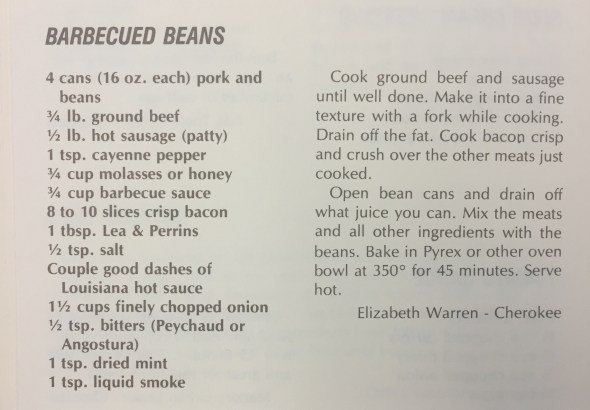

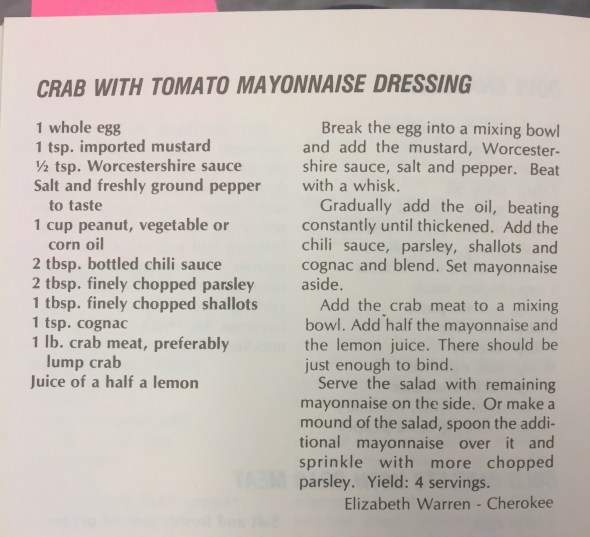

The best argument she’s got in her defense is that, based on the public evidence so far, she doesn’t appear to have used her claim of Native American ancestry to gain access to anything much more significant than a cookbook; in 1984 she contributed five recipes to the Pow Wow Chow cookbook published by the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, signing the items, “Elizabeth Warren — Cherokee.”

“I like my corn with olives!” source

What is the best way to handle it, the best strategy, when the President is treating you like a third grade bully, repeatedly and publicly calling you a mean name?

Best advice to someone getting bullied? I googled:

We would amend “don’t show your feelings” to stay calm. We would urge any kid to put “tell an adult” as a last resort.

A suggestion:

- if the problem persists, hit back as hard as possible, calmly but forcefully, at the bully’s weakest, tenderest points.

Such a Lisa Simpson / Nelson vibe to Warren / Trump. Are all our elections gonna be Lisa vs. Nelson for awhile?

from this 2003 episode:

Lisa easily wins the election. Worried by her determination and popularity, the faculty discusses how to control her.