Cheney

Posted: November 5, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, presidents 1 CommentThe other intern was active in Young Democrats and naturally wanted to intern with his party, which then controlled the legislature’s lower chamber. The Republicans, who controlled the state senate, agreed to take Cheney, the last man standing, as their intern. Cheney, by his own admission, “didn’t have a political identity.” His parents had been Democrats and if the other intern had been a strong Republican, Cheney would gladly have worked for the Democrats. In essence, Cheney became a Republican by accident.

All these from Stephen F. Hayes’ biography, Cheney: The Untold Story of America’s Most Powerful and Controversial Vice President.

The power of a memo:

When Cheney learned that Rumsfeld had been appointed to run the OEO, he drafted an unsolicited twelve-page strategy memo on the upcoming confirmation hearings. He gave the memo to Steiger, who then passed it to Rumsfeld. Cheney’s memo focused on accountability, and—not coincidentally—so did Rumsfeld’s testimony:

What was the mission exactly at the Office of Economic Opportunity under Richard Nixon?

Rumsfeld sought to have many OEO programs reassigned to other departments, a move that many observers interpreted as the first step in a plan to dismantle the agency. “The president sent Rumsfeld there to close it down,” recalls Christine Todd Whitman, future governor of New Jersey and administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, who began her political career at the OEO as a special assistant. “Some of us thought the programs were worth saving, but we were all aware that the agency’s time was limited.”

Nixon:

Nikita Khrushchev, Nixon said, had once given him a sage bit of advice: in order to be a statesman, it is sometimes necessary to be a politician. “If the people believe there’s an imaginary river out there, you don’t tell them there’s no river there,” Cheney remembers Nixon saying. “You build an imaginary bridge over the imaginary river.” In late June 1972, the CLC froze food prices again.

A philosophy forms:

His experience in the Nixon administration began to change that. He saw well-intentioned government programs that solved one problem and created a dozen others. A plan by the Office of Economic Opportunity to train migrant workers to grow azaleas in South Carolina would have provided jobs for the workers but destroyed the market for azaleas in the process. Need-based assistance in the poorest parts of the country was diverted to “community-action programs” that did little more than line the pockets of local politicians. Through the Cost of Living Council, the IRS targeted small businesses because their owners wanted to give employees a raise. Grocery stores had to fight with the federal government to raise the price of a dozen eggs. To protect the American public, the Price Commission directed McDonald’s to reduce the price of Quarter-Pounders. To Cheney, these experiences not only demonstrated the inherent inefficiencies of big government but seemed to confirm the wisdom of individualism and self-reliance, the cardinal virtues of his home state.

(why not extrapolate that to how things would go when Big Government invades other countries?)

(it is really wild that the Nixon administration had federal government price controls on everyday goods and McDonald’s burgers! Every time I’m reminded of the Nixon era price controls I feel crazy)

Cheney was thirty-three years old when he began his work for the Ford administration. He had sat in on meetings with Ford when they were both working in the House. But Cheney didn’t meet his new boss until after starting full-time at the White House. Ford was a trusting soul, a rarity in the cutthroat politics of Washington, and he immediately saw Cheney as part of his inner circle. “He is as comfortable with Cheney as he is with Rumsfeld,” one senior aide of Ford’s said. “He doesn’t hesitate to say ‘Get me Cheney,’ if something comes up and Dick is the one close at hand.”

…

Little more than a decade earlier, Cheney had been a college dropout living in a tent and working as a grunt laying power lines in rural Wyoming. Now, he was working directly for the leader of the free world, coordinating the unceremonious dismissal of the man in charge of energy policy for the United States. It’s hard to imagine a more dramatic change in direction, but Cheney doesn’t remember spending much time reflecting on where he had been and where he was headed

How he stifled Nelson Rockefeller:

Frustrating the policy proposals of the vice president became a significant part of Cheney’s job in the Ford White House. Rockefeller, said Cheney: …would periodically produce these big proposals and he’d go in for his weekly meeting for the president and oftentimes give him these proposals. At the end of the day I’d go down for the wrap-up session and the president would say: “Here, what are we going to do with this?” And I’d say, “Well, we’ll staff it out.” So I would take it and put it into the system. It would go through OMB and it would go to the Treasury and all of the other places that had a say in his Council of Economic Advisers. Of course the answer would always come back, “This is inconsistent with our basic policy of no new starts,” so it would get shot down. He would later describe this role as putting “sand in the gears.” The phrase “we’ll staff it out” quickly became a euphemism for killing one of Rockefeller’s projects.

Back to Wyoming to run for office:

Although they complained about their father’s driving music—an eight-track tape of the Carpenters—the girls liked to go along.

Health tips:

As he began to mend, Cheney consulted with his doctor, Rick Davis. “He said, ‘Look, hard work never killed anybody.’ He said, ‘What is bad for you, what causes stress is doing something you don’t enjoy, having to spend your life living in a way you don’t want to live it.’”

…

He began a light exercise regimen, walking the five blocks from his house to the campaign headquarters and back.

Secretary of Defense:

As he stood behind the oversize desk that once belonged to General John Pershing, the legendary commander in World War I, he ordered an aide to fetch the Pentagon organization chart. The aide returned and flopped the mammoth diagram in front of his boss. “It sort of fell off both ends of the desk,” says Cheney. “And I rolled it up and stuck it in the trash and never looked at it again. I decided right then and there that I wasn’t going to spend a lot of time trying to reorganize the place.”

Odd incident on 9/11:

As the afternoon wore on, Condoleezza Rice noticed that Cheney hadn’t eaten anything. “You haven’t had any lunch,” she said to the vice president. As soon as she said it, she realized that it probably sounded odd. “I thought, ‘Where did that come from? What a strange thing to say in the middle of this crisis.’”

(Whether or not the US military shot down any civilian aircraft on that day (a mild conspiracy theory, that they shot down Flight 93), there was period on the day when Cheney certainly thought that they had, and on his orders. It seems to me that this traumatized him, or at least deeply affected his thinking.)

“I’ve seen him listen to some tirades from senators that would try anyone’s patience,” says McCain. “He stands there, smiles. Polite.” McCain sits up; straightens his face; and, speaking in an exaggerated monotone, does his best impersonation of Dick Cheney: “Thanks very much. Thank you. Yes.”

“I’ve seen a guy come up to him and say, ‘We’ve got to reauthorize the ag bill. Understand? My farmers, they’ve got to have this emergency funding. You’ve got to get the president to say, ‘We need this ag bill.’ He smiles,” says McCain, continuing as Cheney. “‘ Thank you very much. Yes. Yes, Pat.’ In fact, now that I think about it, I’ve never seen him fire back at any one of these guys when they do that. I just never have.” Cheney, of course, has a reason for subjecting himself to this gantlet. “What I try to do is maintain those relationships when you don’t need them so that they’re there when you do need them,” he says.

lifestyle:

Cheney sips Johnny Walker Red and snacks from a jar of Planters dry-roasted peanuts. (“ Yeah, and he doesn’t share,” laughs one friend.)

On fish:

Words stream out of Cheney’s mouth as he describes his favorite fish. “A steelhead is a magnificent fish. It’s a sea-run rainbow that spawns in fresh water. It hatches out, spends maybe a couple of years in fresh water. And then goes to sea, just like Atlantic salmon. A couple years in the ocean, cruising the Pacific, grows to considerable size and then comes back to fresh water. Probably the biggest steelhead I’ve caught—a few in the twenty-pound class,” he says, then clarifies, “twenty-pounds-plus. That’s a big fish on a fly rod. They catch a few up there every year where we go, over thirty pounds. I’ve never caught a thirty-pounder. And it’s very tough technical fishing. You might fish all day long and not have a strike, but, boy, once you’ve got one on it’s just—it’s an amazing experience when you’ve got a twelve-, fifteen-pound steelhead on the end of your line, tail-walking down the river, putting up a hell of a fight. And you do it in some of the most beautiful country. If I had one fishing trip left in me I want to go spend a week on the Babine.”

(source)

Previous coverage of Cheney:

The importance of bird hunting in American politics.

Glimpses of Abraham Lincoln: awaiting election results with Charles Dana

Posted: April 3, 2025 Filed under: presidents, WOR Leave a comment

Charles Dana, former journalist and assistant secretary of war was with Abraham Lincoln as he awaited results of the election of 1864:

All the power and influence of the War Department, then something enormous from the vast expenditure and extensive relations of the war, was employed to secure the re-election of Mr. Lincoln. The political struggle was most intense, and the interest taken in it, both in the White House and in the War Department, was almost painful. After the arduous toil of the canvass, there was naturally a great suspense of feeling until the result of the voting should be ascertained. On November 8th, election day, I went over to the War Department about half past eight o’clock in the evening, and found the President and Mr. Stanton together in the Secretary’s office. General Eckert, who then had charge of the telegraph department of the War Office, was coming in constantly with telegrams containing election returns. Mr. Stanton would read them, and the President would look at them and comment upon them. Presently there came a lull in the returns, and Mr. Lincoln called me to a place by his side.

“Dana,” said he, “have you ever read any of the writings of Petroleum V. Nasby?”

“No, sir,” I said; “I have only looked at some of them, and they seemed to be quite funny.”

“Well,” said he, “let me read you a specimen”;

“let me read you a specimen”;

and, pulling out a thin yellow-covered pamphlet from his breast pocket, he began to read aloud. Mr. Stanton viewed these proceedings with great impatience, as I could see, but Mr. Lincoln paid no attention to that.

He would read a page or a story, pause to consider new election telegram, and then open the book again and go ahead with a new passage. Finally, Mr. Chase came in, and presently somebody else, and then the reading was interrupted.

Mr. Stanton went to the door and beckoned me into the next room. I shall never forget the fire of his indignation at what seemed to him to be mere nonsense.

The idea that when the safety of the republic was thus at issue, when the control of an empire was to be determined by a few figures brought in by the telegraph, the leader, the man most deeply concerned, not merely for himself but for his country, could turn aside to read such balderdash and to laugh at such frivolous jests was, to his mind, repugnant, even damnable. He could not understand, apparently, that it was by the relief which these jests afforded to the strain of mind under which Lincoln had so long been living, and to the natural gloom of a melancholy and desponding temperament-this was Mr. Lincoln’s prevailing characteristic-that the safety and sanity of his intelligence were maintained and preserved.

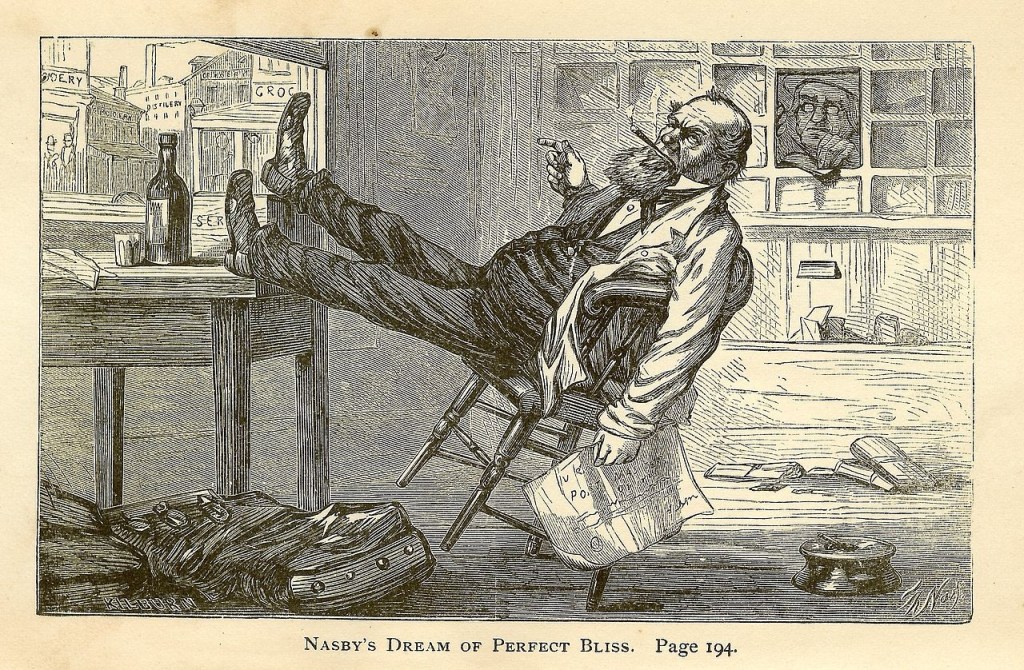

Petroleum Naseby was a character, a cowardly Copperhead who supported the Confederacy but didn’t want to do anything about it, invented by David Ross Locke.

In his day Locke was up there with Josh Billings and Mark Twain.

Lincoln in New Orleans (featuring final answer on was Abraham Lincoln gay?)

Posted: January 18, 2025 Filed under: Mississippi, New Orleans, presidents Leave a comment

In the year 1828 nineteen year old Abraham Lincoln went on a flatboat trip with a local twenty one year old named Allen Gentry. He would be paid eight dollars a month plus steamboat fare home. They left from Spencer County, Indiana, down the Ohio to the Mississippi.

The great New Orleans geographer and historian Richard Campanella wrote a whole book, Lincoln In New Orleans, about Lincoln’s experience on this trip and another down in New Orleans. It’s a really illuminating work on Lincoln, the Mississippi River at that time, the floatboatman life, early New Orleans.

If you need step by step instructions on building a flatboat, they’re in Campanella’s book. (People back then worked so hard!)

Campanella tells us in vivid reconstruction from various sources what this trip must’ve been like:

the Mississippi River in its deltaic plain no longer collected water through tributaries but shed it, through distributaries such as bayous Manchac, Plaquemine, and Lafourche (“the fork”). This was Louisiana’s legendary

“sugar coast,” home to plantation after plantation after plantation, with their manor houses fronting the river and dependencies, slave cabins, and

“long lots” of sugar cane stretching toward the backswamp. The sugar coast claimed many of the nation’s wealthiest planters, and the region had one of the highest concentrations of slaves (if not the highest) in North America. To visitors arriving from upriver, Louisiana seemed more Afro-Caribbean than American, more French than English, more Catholic than Protestant, more tropical than temperate. It certainly grew more sugar cane than cotton (or corn or tobacco or anything else, probably combined).

To an upcountry newcomer, the region felt exotic; its society came across as foreign and unknowable. The sense of mystery bred anticipation for the urban culmination that lay ahead.

What Lincoln did in New Orleans is recorded only in a few stray remarks from the man himself and secondhand stories remembered afterwards by those he told them to, who then told them to William Herndon, biographer and law partner of Lincoln. (now they can be found in a volume called Herndon’s Informants). What was Lincoln like in New Orleans?

Observing the behavior of young men today, sauntering in the French Quarter while on leave from service, ship, school, or business, offers an idea of how flatboatmen acted upon the stage of street life in the circa-1828 city. We can imagine Gentry and Lincoln, twenty and nineteen years old respectively, donning new clothes and a shoulder bag, looking about, inquiring what the other wanted to do and secretly hoping it would align with his own wishes, then shrugging and ambling on in a mutually consensual direction. Lincoln would have attracted extra attention for his striking physiognomy, his bandaged head wound from the attack on the sugar coast, and his six-foot-four height, which towered ten inches over the typical American male of that era and even higher above the many New Orleanians of Mediterranean or Latin descent.

Quite the conspicuous bumpkins were they.

One cannot help pondering how teen-aged Lincoln might have behaved in New Orleans. Young single men like him (not to mention older married men) had given this city a notorious reputation throughout the Western world; condemnations of the city’s wickedness abound in nineteenth-century literature. A visitor in 1823 wrote,

New Orleans is of course exposed to greater varieties of human misery, vice, disease, and want, than any other American town. … Much has been said about [its] profligacy of manners, morals… debauchery, and low vice … [T]his place has more than once been called the modern Sodom.

Campanella considers what we know about Lincoln and women:

I consider the matter concluded that Abe was a gentle shyguy ladykiller.

I found this passage very real:

Campanella gives us the political context of the time:

There was much to editorialize about in the spring of 1828. A concurrence of events made politics particularly polemical that season. Just weeks earlier, Denis Prieur defeated Anathole Peychaud in the New Or-leans mayoral race, while ten council seats went before voters. They competed for attention with the U.S. presidential campaign— a mudslinging rematch of the bitterly controversial 1824 election, in which Westerner Andrew Jackson won a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote in a four-candidate, one-party field, but John Quincy Adams attained the presidency after Congress handed down the final selection. Subsequent years saw the emergence of a more manageable two-party system. In 1828, Jackson headed the Democratic Party ticket while Adams represented the National Republican Party (forerunner of the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party). Jackson’s heroic defeat of the British at New Orleans in 1815 had made him a national hero with much local support, but did not spare him vociferous enemies. The year 1828 also saw the state’s first election in which presidential electors were selected by voters-white males, that is—rather than by the legislature, thus ratcheting up public interest in the contest. 238 Every day in the spring of 1828 the local press featured obsequious encomiums, sarcastic diatribes, vicious rumors, or scandalous allegations spanning multiple columns. The most infamous-the “coffin hand bills,” which accused Andrew Jackson of murdering several militiamen executed under his command during the war—-circulated throughout the city within days of Lincoln’s visit. 23% New Orleans in the red-hot political year of 1828 might well have given Abraham Lincoln his first massive daily dosage of passionate political opinion, via newspapers, broadsides, bills, orations, and overheard conversations.

Before they got to New Orleans, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked by a group of seven Negroes, possibly runaway slaves? Little is known for sure about the incident, except that they messed with the wrong railsplitter. Lincoln was famously strong and a good fighter:

In a remarkable bit of historical detective work, Campanella concludes that a woman sometimes called “Bushan” may have been Dufresne, and puts together this incredible map:

Really impressed with Campanella’s work, I also have his book Bienville’s Dilemma, and add him to my esteemed Guides to New Orleans. Campanella goes into some detail about how and in what forms Lincoln would’ve encountered slavery on this trip. Any dramatic statement about it he made during the trip though seems historically questionable. When Lincoln talked about this trip in political speeches, he used it as an example of how he’d once been a working man. For example, 1860 in New Haven:

Free society is such that a poor man knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition-when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him!’

Campanella does cite a letter Lincoln wrote in 1860 where he did speak on what he saw of slavery:

Making a flatboat trip was a rite of passage for a young buck of the Midwest at that time. Whether it brought Lincoln to full maturity is discussed in a poignant and comic anecdote:

An awkward incident one year after the New Orleans trip yanked the maturing but not yet fully mature Abraham back into the petty world of past grievances. How he dealt with it reflected his growing sophistication as well as his lingering adolescence. Two Grigsby brothers— kin of Aaron, the former brother-in-law whom Abraham resented for not having done enough to aid his ailing sister Sarah Lincoln-married their fiancées on the same day and celebrated with a joint “infare.” The Grigsbys pointedly did not invite Lincoln. In a mischievous mood, Abraham exacted revenge by penning a ribald satire entitled “The Chronicles of Reuben,” in which the two grooms accidentally end up in bed together rather than with their respective brides. Other locals suffered their own indignities within the stinging verses of Abraham’s poem, nearly resulting in fisticuffs. The incident botses tected and exacerbated Lincoln’s growing rift with all things related to Spencer County.

An article version of Campanella’s book is available free.

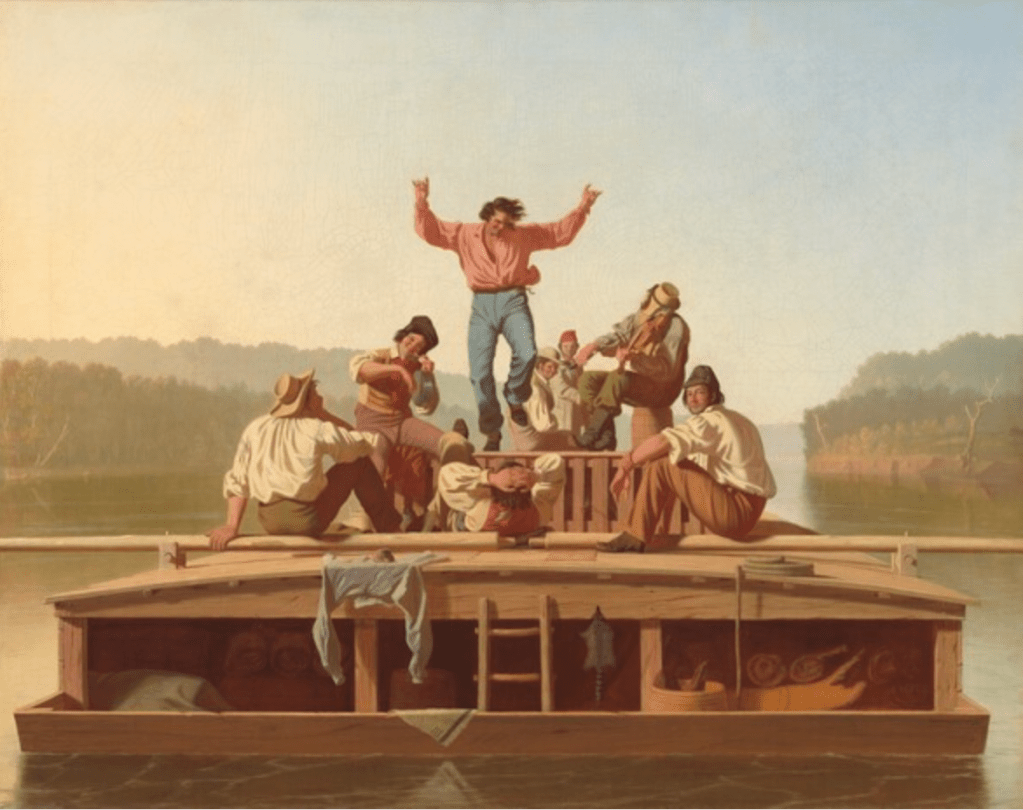

That painting is of course Jolly Flatboatmen, which we discussed back in 2012.

Stuart Spencer (1927-2025)

Posted: January 14, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, presidents, the California Condition 2 Comments

I read in The LA Times that Stuart Spencer died. His Miller Center Oral History interview is one of the most vivid on the rise of Ronald Reagan, California, politics in general:

After many discussions with [Reagan], we realized this guy was a basic conservative. He was obsessed with one thing, the communist threat. He has conservative tendencies on other issues, but he can be practical.

When you look at the 1960s, that’s a pretty good position to be in, philosophically and ideologically. Plus, we realized pretty early on that the guy had a real core value system. Most people in my business don’t like to talk about that, but you know something? The best candidates have a core value system. Either party, win or lose, those are still the best candidates. They don’t lose because of their core value system. They lose because of some other activity that happens out there. But the best candidates to deal with, and to work with, are those who have that. A lot of them have it and a lot of them don’t, but Reagan had it.

The power players of Southern California:

Holmes Tuttle was a man of great . . . He was a car dealer, a Ford dealer in southern California and he also had some agencies in Tucson, I think. Holmes was a guy that came from Oklahoma on a freight car. He had no money and he started working—I don’t think he finished high school—for a car dealership, washing cars, cleaning cars. He’s a man of tremendous energy, tremendous drive and strong feelings—which most successful businessmen have—about how the world should be run, how the country should be run as well as how their business should be run and how your business should be run. They’re always tough and strong that way. That was Holmes’ background.

In the southern California—I won’t say California because we have two segments, north and south—framework of the late ’30s and the ’40s, there were movies made about a group. I can’t remember what they were called, but there were 30 of them. In this group were the owner and publisher of the L.A. Times, the [Harry] Chandler family top business guys, Asa Call of what is now known as Pacific Insurance. It was Pacific Mutual Insurance then, a local company. Now it’s a national company. Henry Salvatori, the big oil guy; Holmes; Herbert Hoover, Jr.; the Automotive Club of Southern California; that type of people, they ran southern California. They had the money. They had the mouth, the paper. They ran it. [William Randolph] Hearst was a secondary player. He had a paper, but he was secondary player. He wasn’t in the group. Hearst was more global.

These guys worried about everything south of the Tehachapi Mountains. That’s all they worried about. They worried about water. They worried about developments. They’ve made movies about that. Most of it’s true. The Southern Pacific was the big power player, but these guys were trying to upset the powers of the Southern Pacific to a degree. Holmes Tuttle came out of that power struggle, that power group.

He was a guy who would work hard. Asa Call was the brains. Holmes was the Stu Spencer, the guy that went out and made it happen. He was aggressive and he played a role. He started playing a role in the political process in the ’50s, post Earl Warren. None of these guys were involved with Earl Warren to any degree. But after Earl Warren and Nixon, they were players there. They never were in love with Nixon, but they were pragmatic. The Chandlers were in love with Nixon, and a few others, but with these bunch of guys, Ace would like Nixon. Holmes was the new conservative and Nixon was a different old conservative.

There were little differences there. Holmes emerged in the new conservative element and was heavily involved in the Goldwater campaign of ’64. Of course that’s a whole ’nother story. When Nixon went down the tube all of a sudden—it was lying there latent in the Goldwater movement and they were waiting for Nixon to get beat and when he did [sound effect]—here they were up in your face.

Reagan was the first legitimate person that Holmes was absolutely, totally, in synch with, and who he totally loved.

On Ron and Nancy:

Here’s an important point in my story. We met with the Reagans. The Reagans are a team politically. He would have never made the governorship without her. He would have never been victorious in the presidential race without her. They went into everything as a team.

It was a great love affair, is a great love affair. Early on I thought it was a lot of Hollywood stuff. I really did. I could give you anecdotes of her taking him to the train when he had to go to Phoenix because they didn’t fly in those days, or to Flagstaff to do the filming of the last segments of that western he was doing. We’d be in Union Station in L.A. at nine o’clock at night. They’re standing there kissing good-bye and it goes on and it goes on and it goes on. I’m embarrassed and I’m saying,

Wow.It was just like a scene out of Hollywood in the 1930s, late ’30s, ’40s. I tell you that, but then I tell you now twenty-five, thirty, forty years later, whatever it is, it was a love affair. It was not Hollywood.At that time I thought, oh, boy. It’s not only a partnership, it’s a great love affair. She was in every meeting that Bill and I were at with Reagan, discussing things, us asking questions, with him asking us questions. The curve of her involvement over the years was interesting because she was in her 40s then probably. She always lied about her age so I can’t tell you exactly, but she was somewhere around 45, I’d guess. She was quiet. With those big eyes of hers, she’d be watching you. Every now and then she’d ask a question, but not too often.

As time went on—I’m talking about years—she grew more and more vocal. But she was on a learning curve politically. She learned. She’s a very smart politician. She thinks very well politically. She thinks much more politically than he thinks. I think it’s important that Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan were the team that went to the Governor’s office and that went to the White House. They did it together. They always turned inward toward each other in times of crisis. She evolved a role out of it, her role. No one else will say this, but I say this: she was the personnel director.

She didn’t have anything to do with policy. She’d say something every now and then and he’d look at her and say,

Hey, Mommy, that’s my role.She’d shut up. But when it came to who is the Chief of Staff, who is the political director, who is the press secretary, she had input because he didn’t like personnel decisions. Take the best example, Taft Schreiber, who was his agent out at Universal for years, and Lew Wasserman. After we signed on, Taft was in this group of finance guys and he said to me,Kid, we’ve got to have lunch.I had lunch with Taft and he proceeded to tell me,

You’re going to have to fire a lot of people.I said,What do you mean?He said,Ron—meaning Reagan—has never fired anybody in his life.He said,I’ve fired hundreds of people. He’s never fired anybody.I laughed. I said to myself, Taft’s overstating the case. Taft was right. I fired a lot of people after that.Reagan hated personnel problems. He hated to see differences of opinion among his staff. His line was,

Come on, boys. Go out and settle this and then come back.You’re going to have a lot of that in politics. You’re going to have a lot of that in government. That’s what makes the wheels go round. It doesn’t mean that they’re not friends or anything. They have differences of opinion, but Reagan didn’t like that too much, especially over the minutia, and it usually happens over the minutia.

The sum total of Reagan:

The sum total of him is simply this: here’s a man who had a basic belief, who thought America was a wonderful, great country. I don’t think you can go back through 43 Presidents and find a President of the United States who came from as much poverty as Reagan came from; income-wise, dysfunctional families. I can’t quite remember where [Harry] Truman came from, but you’re not going to find one.

This guy came from an alcoholic family, no money, no nothing. He was a kid who was a dreamer. He dreamed dreams and dreamed big dreams and went out to fulfill those dreams with his life and he did it. As he moved down his career and got really involved in the ideological side of the political spectrum, which is where he started, he had real concerns about all this leaving us because of communism.

You look back—some of it sounds a little silly—but at the time there was perceived all kinds of threats, all over the world about communism moving into Asia, moving into Africa. That was the driving force behind his political participations. It was the only thing that he really thought about in depth, intellectualized, thought about what you can do, what you can’t do, how you can do it.

With everything else, from welfare to taxation, he went through the motions. Now, this is me talking, but every night when he went to bed, he was thinking of some way of getting [Leonid Ilyich] Brezhnev or somebody in the corner. He told me this prior to the beginning of the presidency. Because I asked questions like, What the hell do you want this job for?

I’d get the speech and the program on communism. He could quote me numbers, figures. He’d say, We’ve got to build our defenses until they’re scary. Their economy is going down and it’s going to get worse. I’m simplifying our discussion. He watched and he fought for defense. God, he fought for defense. He cut here, he cut there for more defense. He took a lot of heat for it. All the time he delivered, in his mind, the message to Russia, we’re not going to back off. We’ll out-bomb you. We’ll out-do everything to you.

His backside knew that we have the resources, this country has the resources and the Russians don’t. If they try to keep up with us defensively, they’re going to be in poverty. They’re going to be economically dead and an economically dead country can only do one of two things, either spring the bomb or come to the table. He was willing to roll those dice because he absolutely had an utter fear of the consequences of nuclear warfare.

Again he was lucky. He couldn’t deal with Brezhnev. He was over the hill and out of it. [Yuri Vladimirovich] Andropov was gone, dead. Reagan lucked out. In comes this guy [Mikhail] Gorbachev who was smart enough to see the trend in his own country. He started talking with Reagan about cutting a deal. That’s what it got down to. In that context Reagan was very benevolent. He was willing to give up a lot. If this guy was serious and willing to go down this road, he was willing to give up things to get the job done, which was to get rid of the cold war. To him the cold war was the threat of nuclear holocaust in this country and other countries.

That was a dream that he had before he was in the presidency. These words I’m giving you and interpreting for you were given to me prior to his election to the presidency. If you do a lot of research, you’ll see that he was always asking questions of the intelligence people, What’s the state of the economy in Russia? He must’ve had a Dow Jones bottom line in his mind—what he thought it was going to take to do it—because he always knew how many nukes we had and where they were. He was really into this.

Young

Does that mean that Reagan was a visionary?

Spencer

I don’t know. He was a dreamer. He was a dreamer. He dreamed that he was going to be the best sportscaster in America, that he was going to be one of the better actors in Hollywood. You know he got tired of playing the bad guy alongside Errol Flynn, who got the women all the time. But he still dreamed big dreams. That’s the way he was.

On Reagan’s interpersonal style:

Young

He was good at communications obviously. How was he at working the room with politicians?

Spencer

Terrible. Ronald Reagan is a shy person. People don’t understand this. He was not an introvert. Nixon was almost an introvert and paranoid. That’s a bad combination. Reagan was shy. People who I met through the years said to me,

I saw President Reagan at this,orI saw President Reagan one-on-one, two or three people in the Oval Office,or something. He never talked about anything substantive. He just told jokes.Ronald Reagan used his humor and his ability to break the ice. He wasn’t comfortable with you and you coming in the Oval Office with strangers and talking.

Number one, he’s not going to tell you about what he’s doing. He doesn’t think it’s any of your damn business. Secondly, he’s not comfortable and so he uses his humor. He can do dialects. I mean the Jewish dialect, a gay dialect. He can tell an Irish ethnic joke. The guy was just unbelievably good at it and he’d break the ice with it. You’d listen to him. But if you were that type of person, you’d walk out of there and you’d say,

What the hell were we talking about? He didn’t tell me anything.“

The Reagans had very few friends:

The Reagans never had a lot of friends. I cannot sit here today and tell you of a good, close, personal friend. They had each other and a lot of acquaintances. Maybe Robert Taylor was, maybe Jimmy Stewart was, some of those people. Maybe Charlie Wick and his wife, but other than that, I don’t know of any that they had. The Tuttles? They were not what you’d call close friends of theirs. They did things together but . . . it was he and Nancy.

An aside on Jimmy Carter:

The primary campaign for Jimmy Carter, 1976, was one of the best campaigns I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. They did an outstanding job. The guy in January was nine per cent in the polls in terms of his name ID. He ends up getting the nomination. Lots of things had to go right for them. Lots of breaks they had to get, breaks that they didn’t create, but they got them.

All that considered, the primary campaign was just an outstanding one. It was a lot of Jimmy Carter’s effort. He worked his tail off. Things kept setting up for him. The Kennedys kept vacillating and going this way and that. Everything kept setting up for him. They ran an outstanding campaign.

They had problems in ’80 because issues caught up with them. Their governance was not as good as their ability to run, which happens. I attribute most of it to his micromanagement. All of the Reagan people learned a lot from watching that because we had the opposite. [laughs]

The whole thing is great, on Bush, Dan Quayle, Clinton, Thatcher, it’s like 129 pages long.

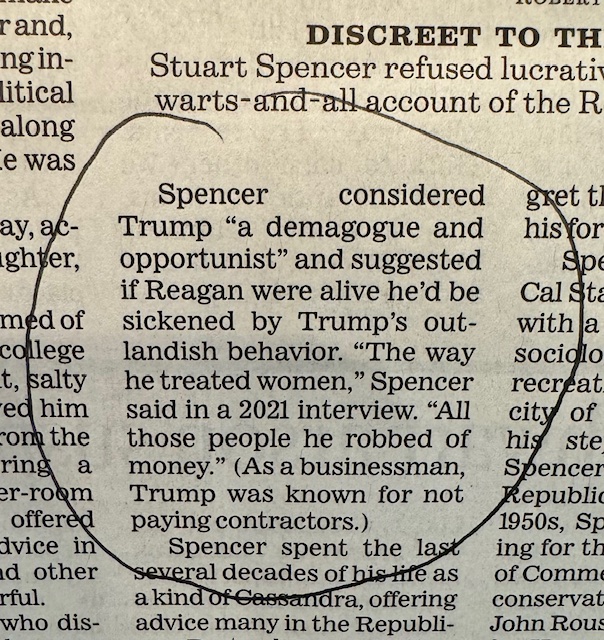

Two items to note from the obituary, by Mark A. Barabak:

and:

Spencer voted third party in 2016, for Joe Biden in 2020 and for Kamala Harris in 2024.

Some final advice from Spencer:

Finally I gave some major paper interview. It was on the plane. Marilyn [Quayle] was there and Dan Quayle was there. I was here and the press guy was here. The press guy starts out kind of warm and fuzzy and he says,

Who are your favorite authors?He looks at Marilyn, and he says,Who are my favorite authors?Oh, God.The second question is something about music. My position is, if you really haven’t thought about it in your own life, about who your favorite authors are, you can always say [Ernest] Hemingway. There are some names out there that you can use. If it’s music, you can say the Grateful Dead. Say anything you want to and think about it afterwards.

I was wrong, I like this guy better.

Jimmy Carter reconsidered

Posted: January 6, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, presidents 1 Comment

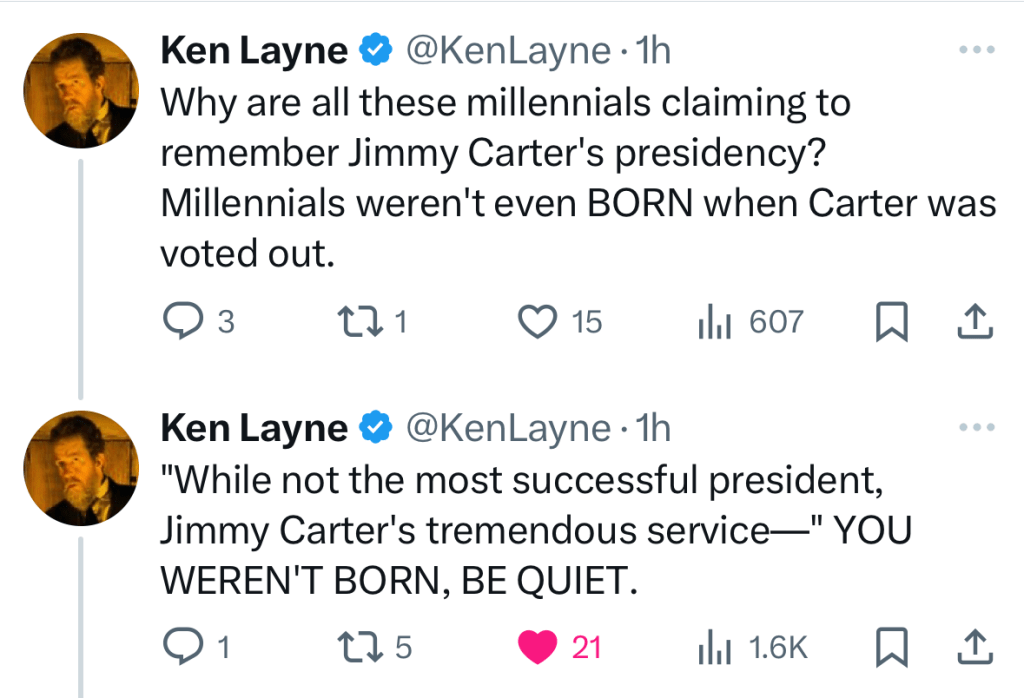

Tyler Cowen didn’t like him. George Will didn’t like him. Ken Layne made me laugh:

Aren’t we always interested in the history that came right before we appear?

Delta Airlines has not one but two documentaries about Jimmy Carter available to view: Carterland and Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President. (Do these movies make money? Who is funding them?) I was able to watch most of both of them (without sound, with subtitles) on recent transcontinental travels. Rock and Roll President was particularly interesting, for example how Carter did not turn on Gregg Allman even after he was busted for and then testified in a case involving pharmaceutical cocaine, or the role John Wayne played in helping the Panama Canal treaty to pass

All this has me to prepared to somewhat revise my view of Carter’s presidency. His inability to “do something” about the Iranian hostage crisis was because he was unwilling to start a war or kill a lot of innocent Iranians. Though his temperament may not have suited him to win reelection, he improved life in the United States, made a lot of difficult choices on tough problems, avoided war (Panama could’ve been one). His presidency was devoted to peace, and helped heal the United States.

The contradictions are endless but was it not good for us, in that moment, to have a prayerful man of peace and leadership that reached for the spiritual?

Similar to the way Gerald Ford was later honored for his courage (?) in pardoning Richard Nixon, should Jimmy Carter be honored for absorbing political consequences of hard decisions and hard efforts that kept the peace?

At the Carter Library the fact that Carter never dropped a bomb or fired a missile during his presidency is highlighted. He’s the last president of whom that can be said. The American people don’t seem to want that.

Perhaps his story is a Christian story, of the martyr, the saint, who suffers as he absorbs our sins. A traveling preacher who came to town.

Perhaps all post-1945 US presidents should be judged on one standard only: whether there was a nuclear war on their watch. We must give Carter an A!

In his Miller Center interview, Jimmy Carter notes several times that the governor of Georgia is very powerful – more powerful, relative to the legislature, than the president is to Congress:

Fenno

Mr. President, I just wanted to follow up one question about the energy preparation. In your book you note that when you came to present the energy package, you were shocked, I think the word was shocked, by finding out how many committees and subcommittees this package would have to go through.

Carter

Yes.

Fenno

I guess my question is in the preparation that you went through, didn’t Congressmen tell you what you were going to find? Why were you shocked?

Carter

Well, I don’t know if I expressed it accurately in the book. I don’t think it was just one moment when all of a sudden somebody came in the Oval Office and said there was more than one committee in the Congress that has got to deal with energy. I had better sense than to labor under that misapprehension. But I think when Tip O’Neill and I sat down to go over the energy package route through the House, I think Jim Wright was there also, there were seventeen committee or subcommittee chairmen with whom we would have to deal. That was a surprise to me, maybe shock is too strong a word. But in that session or immediately after that, Tip agreed as you know to put together an ad hoc committee, an omnibus committee, and to let [Thomas Ludlow] Ashley do the work.

That, in effect, short-circuited all those fragmented committees. The understanding was, after the committee chairmen objected, that when the conglomerate committee did its work, then the bill would have to be resubmitted, I believe to five different, major committees. There were some tight restraints on what they could do in the way of amendment. So that process was completed as you know between April and August, an unbelievable legislative achievement.

In the Senate though, there were two major committees and there had to be five different bills and unfortunately, Scoop Jackson was on one side and Russell Long was on the other. They were personally incompatible with each other and they had a different perspective as well. Scoop had been in the forefront of those who were for environmental quality and that sort of thing, and Russell represented the oil interest. That was one of the things that caused us a problem. But we were never able to overcome the complexities in the Senate. In the House, we did short circuit the process. I never realized before I got to Washington, to add one more sentence, how fragmented the Congress was and how little discipline there was, and how little loyalty there would be to an incumbent Democratic President. All three of those things were a surprise to me.

Truman

Were those in sharp contrast to the experience in the Georgia legislature?

Carter

Well, there’s no Democratic-Republican alignment of the Georgia legislature. It’s all Democrats, and therefore, there is no party loyalty. You had to deal with individual members. The Governor is really much more powerful in Georgia than the President is in the United States. As Georgia Governor, I had line-item veto, for instance, in the appropriations bills. And, as you also know, in Georgia and in Washington, most of the major initiatives come from the executive branch. There’s very seldom a major piece of legislation that ever originates in the legislature. I think that there is a parallel relationship between the independent legislature confronting an independent Governor or the independent Congress confronting an independent President. At the state level, the Governor, at least in Georgia, is much more powerful than the President in Washington.

Neustadt

Did you have the same kind of subcommittee structure?

Carter

No. It’s not nearly so complicated.

Neustadt

That helps you too.

Carter

The seniority and the guarding of turf and so forth is not nearly so much of a pork barrel arrangement in the state legislature. Also, the Georgia legislature only serves forty days a year. They come and do their work in a hurry, and then they go home.

Truman

A simple legislature doesn’t have much staff either.

Carter

They are growing rapidly in staff, but nothing like the Congress. And you don’t have the insidious, legal bribery in the Georgia legislature that is so pervasive in the Congress. That’s a problem that’s becoming much more serious and I don’t believe that it’s going to be corrected until we have a major, national scandal in the Congress. I think it’s much worse than most people realize.

The reviews all focus on the presidency but Carter was an extremely effective governor of Georgia.

wish I could read this redacted story:

The ex-presidency of Carter is often cited as admirable, the work on guinea worm is undeniable. James Baker contacted Carter frequently. He helped convince Daniel Ortega to leave office. But then:

In the run-up to the 1991 Gulf War, Carter’s relationship with President Bush turned sour. Carter felt passionately that Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait wasn’t worth going to war over, even though Bush cited the Carter Doctrine in justifying it. The former president said so publicly, then took matters a fateful step further, writing each member of the UN Security Council and urging them to vote against the United States on the resolution.

That is wild! Brian Mulroney told the Bush White House about it and they were unsurprisingly pissed!

The Carter/ Bill Clinton relationship is funny, Alter says Carter’s freelance riffing with North Korea made Clinton apoplectic. Bill and Jimmy, could make an almost not boring play.

Maybe I will stake out the take that Carter was a great president and a mixed bag as an ex-president. Could be fun!

Consider this:

In 2016, the squabbling children of Martin Luther King Jr. needed Carter to mediate. They were at one another’s throats over their family’s possessions, including an old pool table. Brothers Marty and Dexter teamed up to sue sister Bernice, who had possession of their father’s Bible (used by Barack Obama to take the oath of office) and his Nobel Peace Prize. Carter’s approach was the same as at Camp David: both sides would agree at the end of the process to one document. This time, the document went through six or seven drafts, with the parties finally agreeing that Carter’s decisions on what would be sold or kept were to be final. One night Carter would be hard on Bernice; the next, on Dexter or Marty. Carter finally determined — and a judge soon ratified that Marty, as chairman of the estate, had control of the Bible and the Nobel, but they would be displayed at the King Center in Atlanta, not sold.

The one document method might be something practical we can all learn from Jimmy Carter. I haven’t felt like time spent studying this American original has been wasted. The more I learn about him the more complex he becomes.

(photo of Dolly and Jimmy borrowed from Parton News instagram)

Reedy, Twilight of the Presidency

Posted: August 18, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, presidents Leave a commentIt’s time to revisit George Reedy, Twilight of the Presidency.

I can’t do better as a summary than this 1970 review by William C. Spragens in The Western Political Quarterly found on JSTOR:

The edition I read is updated for the Reagan administration. Some choice passages:

In talking to friends about the presidency, I have found the hardest point to explain is that setbacks often impel presidents to redouble their efforts without changing their policies. This seems to be perversity because very few of us have the opportunity to make decisions of colossal consequences. When our projects go wrong, it is not too difficult for most of us to shrug our shoulders, cut our losses, and take off on a new tack. Our egos may be bruised. But we can live with that. It is a different thing altogether when we can give orders that can lead to large-scale death and destruction or even to economic devastation. Such a situation brings into play psychological factors that are virtually unconquerable.

Suppose, for example, that a president gives the military an order that leads to the deaths of several soldiers in combat. Can any human being who did such a thing say to himself: “Those men are dead because I was a God-damned fool! Their blood is on my hands.” The likely thought is: “Those men died in a noble cau and we must see to it that their sacrifice was not in vain.”

This, of course, could well be the “right” answer. But even if it is the wrong answer, it is virtually certain to be the one that will be accepted. Therefore, more men are sent and then more and then more. Every death makes a pull out more unacceptable.

Furthermore, when a large amount of blood has been spilled, a point can be reached where popular opposition to a policy will actually spur a president to redoubled effort in its behalf. This is due to the aura of history that envelops every occupant of the Oval Office. He lives in a museum, a structure dedicated to preserving the greatness of the American past. He walks the same halls paced by Lincoln waiting feverishly for news from Gettysburg or Richmond. He dines with silver used by Woodrow Wilson as he pondered the proper response to the German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. He has staring at him constantly portraits of the heroic men who faced the same excruciating problems in the past that he is facing in the present. It is only a matter of time until he feels himself a member of an exclusive community whose inhabitants never finally leave the mansion. When stories leaked out that Richard Nixon was “talking to the pictures” in the White House, it was taken by many as evidence that he was cracking up. To anyone who has had the opportunity to observe a president at close range, it is perfectly normal conduct.

(This may be a problem beyond presidents. Do we all have a tendency to double down on our most consequential decisions, even if the results are obviously disastrous?)

The life of the monarch:

As noted, an essential characteristic of monarchy is untouchability. No one touches a king unless he is specifically invited to do so. No one thrusts unpleasant thoughts upon a king unless he is ordered to do so, and even then he does so at his own peril. The response to unpleasant information has been fixed by a pattern with a long history. Every courtier recalls, either literally or instinctively, what happened to the messenger who brought Peter the Great the news of the Russian defeat by Charles XII at the Battle of Narva. The courtier was strangled by decree of the czar. A modern-day monarch-at least a monarch in the White House-cannot direct the placing of a noose around a messenger’s throat for bringing him bad news. But his frown can mean social and economic strangulation. Only a very brave or a very foolish person will suffer that frown.

Some ways in which this effect takes shape:

In retrospect, it is almost impossible to believe that John Kennedy embarked on the ill-fated Bay of Pigs venture. It was poorly conceived, poorly planned, poorly executed, and undertaken with grossly inadequate knowledge. But anyone who has ever sat in on a White House council can easily deduce what happened without knowing 34 THE I any facts other than those which appeared in the public press. White House councils are not debating matches in which ideas emerge from the heated exchanges of participants. The council centers around the president, himself, to whom everyone addresses his observations.

The first strong observations to attract the favor of the president become subconsciously the thoughts of everyone in the room. The focus of attention shifts from a testing of all concepts to a groping for means of overcoming the difficulties. A thesis that could not survive an undergraduate seminar in a liberal arts college becomes accepted doctrine, and the only question is not whether it should be done but how it should be done.

Reedy on White House aides as courtiers, and how Vietnam could’ve happened (he was there!):

Unfortunately, the problem is far deeper than the machinations of courtiers. They do exist in large numbers but most of their energies are absorbed in grabbing for personal favors and building havens of retreat for the future. Generally speaking, they play the role in the White House of the court jesters of the Middle Ages and may even be useful in that they give the chief executive badly needed relaxation. Paradoxically , it is the advisers who are not sycophantic, who are not looking for snug harbors, and who do feel the heavy weight of responsibility who are the most likely to play the reinforcing role. It is precisely because they recognize the ultimacy of the office that they react the way they do.

However they feel, the burden of decision is on another man. Therefore, however much they may argue against a policy at its beginning stages, once it is set they become “good soldiers” and devote their time to making it work.

Those who disagree strongly tend to remain in the structure in the vain hope they can change it coupled with the certainty that they would become totally ineffectual if they left.

This is the bitter lesson we should have learned from Vietnam. In the early days of that conflict, it might have been possible to pull out. My most vivid memories are the meetings early in Lyndon Johnson’s presidency in which his advisers (virtually all holdovers from the Kennedy administration) were looking to him for guidance on how to proceed. He, on the other hand, felt an obligation to continue the Kennedy policies and he was looking to them for indications of what steps would carry out such a course. I will always believe that someone misread a signal from the other side with the resultant commitment to full-scale fighting. After that, all the resources of the federal government were devoted to advising the president on how to do what it was thought he wanted to do.

Reedy on the White House as Versailles:

Sir Thomas Malory seems to have missed the true significance of King Arthur’s Round Table. As long as his knights ate at it every day under King Arthur’s watchful eye and lived in his palace where he could call them by shouting through the corridors, they were his to ensure that the kingdom would be ruled the way he wanted it ruled. Louis XIV did not build the Palace of Versailles as a tourist attraction but as a huge dormitory where he could keep tabs on the nobles who were disposed to become insubordinate if they spent all their time on their own estates. Peter the Great downgraded the boyars whose power rested on their distance from Moscow and brought the reins of government into his own hands by making all the top officials dependent on him. And the Turkish sultans reached the ultimate in the creation of personal force by raising young Christian boys captured in combat as Janissaries who lived solely to defend the ruler.

Reedy has a great chapter titled “What Does The President Do?”:

A president is many things. Basically, however, his functions fall into two categories. First, and perhaps most important, he is the symbol of the legitimacy and the continuity of our government. It is only through him that power can be exercised effectively-but only until opposition forces rally themselves to counter it. Second, he is the political leader of our nation. He must resolve the policy questions that will not yield to quantitative, empirical analysis and then persuade enough of his countrymen of the rightness of his decisions so that they are carried out without disrupting the fabric of society.

At the present time, neither of these functions can be carried out without the president.

He notes that the idea of the President “working” is confusing:

Despite the widespread belief to the contrary, there is far less to the presidency, in terms of essential activity, than meets the eye. The psychological burdens are heavy, even crushing, but no president ever died of overwork and it is doubtful that any ever will. The chief executive can, of course, fill his working hours with as much motion as he desires. The “crisis” days (the American hostages held in Iran or the attempted torpedoing of American navy vessels in the Gulf of Tonkin) keep office lights burning into the midnight hours. But in terms of actual administration, the presidency is pretty much what the president wants to make of it. He can delegate the “work” to subordinates and reserve for himself only the powers of decision as did Eisenhower, or he can insist on maintaining tight control over every minor detail, like Lyndon Johnson.

Presidents on vacation:

It is impossible to take a day and divide it with any sure sense of confidence into “working hours” and “nonworking hours.” But it is apparent from the large volume of words that have been written about presidents that in the past few decades, the only one who seemed able to relax completely was Eisenhower. He was capable of taking a vacation for the sake of enjoying himself, and he disdained any suggestion that he was acting otherwise.

Franklin Roosevelt apparently had little or no time to devote to relaxation. He was notorious for using his dinner hours as a means of lobbying bills through Congress. Once Harry Truman had made a decision he was able to put it out of his mind and proceed to another problem. Furthermore, he too disdained any pretensions of working when he wasn’t. But those who were close to him made it clear that he really didn’t know what to do with himself when he took a holiday. His favorite resort was Key West, Florida, where he would “go fishing” but he would hold a rod only if someone put it in his hands, and about all he really enjoyed was the sunshine and the opportunity to take long walks.

John Kennedy was described as a “compulsive reader” who could not pass up any written document regardless of its relevance to his problems or its contents. Many of his intimates reported that any spare time would find him restlessly prowling the White House looking for something to read. Lyndon Johnson anticipated with horror long weekends in which there was nothing to do. He usually spent Saturday afternoons in lengthy conferences with newspaper reporters who were hastily summoned from their homes to spend hours listening to Johnson expound the thesis that his days were so taken up with the nation’s business that he had no time to devote to friends.

The real misery of the average presidential day is the haunting knowledge that decisions have been made on incomplete information and inadequate counsel. Tragically, the information must always be incomplete and the counsel always inadequate, for in the arena of human activity in which a president operates there are no quantitative answers. He must deal with those problems for which the computer offers no solution, those disputes where rights and wrongs are so inextricably mixed that the righting of every wrong creates a new wrong, those divisions which arise out of differences in human desires rather than differences in the available facts, those crisis moments in which action is imperative and cannot wait upon orderly consideration. He has no guideposts other than his own philosophy and intuition, and if he is devoid of either, no one can substitute.

Reedy summarizes something Robert Caro goes into some detail about (how did an obscure Texas congressman obtain power?):

The office is at such a lonely eminence that no standard rules of the political game govern the approaches to it. Johnson told fascinating stories about the tactics he had used, while still a member of the House, to extract favors from FDR. He made a practice of driving Roosevelt’s secretary, Grace Tully, to the White House every morning. This gave him an opportunity to drop words in her ear, give her memoranda knowing she would pass them on to the “boss,” and learn personal characteristics that he could exploit at a later date. He once filed away in his memory the knowledge that Roosevelt was passionately interested in the techniques of dam construction. A few months later, he wangled his way into the White House with a series of huge photographs of dams that had been supplied to him by an architectural firm in his home district. Roosevelt became so absorbed in comparing the pictures that he absentmindedly okayed a rural electrification project that Johnson wanted but that had been held up by the Rural Electrification Administration for a couple of years.

None of this makes me very sanguine about either Presidential candidate, but over here at Helytimes we consider it better to look truth in the face, best we can, no?

Martin Anderson, a Reagan aide, endorsed the book in a Miller Center interview:

There’s a wonderful book called The Twilight of the Presidency by Reedy. You ever read that?

Young

George Reedy.Anderson

In which he says, If you try to understand the White House—most people make the mistake, they try to understand the White House like a corporation or the military and how does it look, with the hierarchy. He said, The only way to understand it, it’s like a palace court. And if you can understand a palace court, then you understand the White House. I think that’s probably pretty accurate. But those are the things that happen. So anyway, I didn’t go back. So I missed Watergate.Asher

Darn.

Dumb and Dumber and Bill Clinton

Posted: April 11, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, presidents Leave a comment

(source)

We’d sit on that airplane and watch—one example, the classically brilliant, stupid movie, Dumb and Dumber.

Riley

I love Jim Carrey, but that’s one I haven’t even been able to watch.

Friendly

It’s a hilariously stupid movie, and there’s Clinton sitting there. This is one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever met and he’s sitting there chewing a cigar, playing hearts, watching Dumb and Dumber, laughing hysterically, but then also not getting some of the story line. I mean partly because he’s playing cards, he’s doing a crossword puzzle, talking to somebody, and watching Dumb and Dumber. But there I am trying to describe the plot line of Dumb and Dumber to the President of the United States. This is surreal.

(source: Andrew Friendly interview at The Miller Center)

Then there were silly little things, too, like his crossword puzzles. That seems like a silly thing, but to the extent that there are pop culture clues in crossword puzzles—The Sunday New York Times is the hardest one, because they get harder throughout the week. I never noticed many pop culture references in the Sunday one, but I’m sure the Monday one might have one or two. He loved to watch cheesy movies. We’d be landing in Moscow, but he wanted to see the last minute of Dumb and Dumber before he walked off the plane or something.

Riley

Does that get him charged up, the last minute of Dumb and Dumber?

Goodin

He likes action movies better. All of this is to say he actively cultivated these lifelong friendships. By virtue of who he is and the life he’s led, those friendships are totally across the spectrum of “real people.” He has such capacity to take in everything. He’ll have as much joy talking about the latest biography of [Abraham] Lincoln as he will about the most ridiculous scene in Dumb and Dumber. He has so much real estate in his brain for these people and relationships and knowledge, and he kept himself open to as many channels as possible.

(Stephen Goodin oral history at the Miller Center)

Abraham Lincoln: An Oral History

Posted: December 9, 2023 Filed under: America, history, presidents Leave a comment

T. Lyle Dickey said:

This is an interesting book. We’ve discussed how oral history as we know think of it didn’t seem to exist in the past, it didn’t occur to anyone (a search for “oral history” on Amazon reveals mostly books about music scenes and bands). John Nicolay, who’d been a secretary to Lincoln, worked with John Hay on a biography of Lincoln. They collected stories and reminiscences, but they concluded they couldn’t trust people’s memories. Prof. Burlingame dug through Nicolay’s notes and letters and put this book together.

One J. T. Stuart remembered that Lincoln was almost appointed territorial governor of Oregon during the Fillmore administration, but Mary Todd refused to go out there.

Robert Todd Lincoln remembers visiting his father after Gettsyburg, and finding him just after a cry:

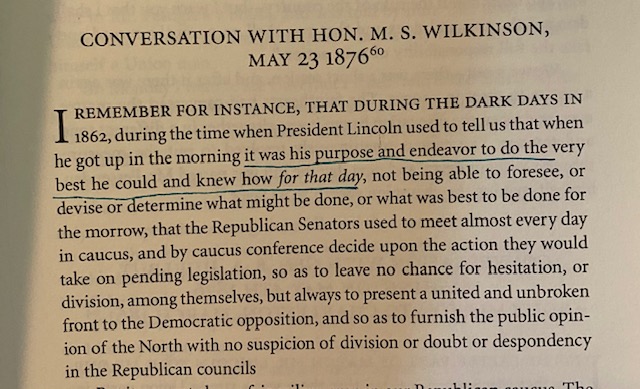

how did he handle the dark days?:

Power and The Presidency

Posted: November 19, 2023 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, presidents Leave a comment

These are a series of essays based on lectures given at Dartmouth. David McCullough introduces us:

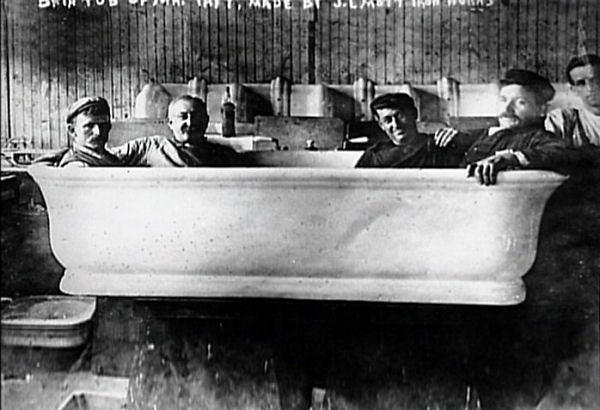

In a wonderful old photograph, the three workmen who did the installation sit together quite comfortably in Taft’s giant tub.

Is this the photo he’s talking about?

Doris Kearns Goodwin on FDR’s power of persuasion:

At the Democratic Convention in 1936, Roosevelt answered the attacks in dramatic form. He admitted he had not kept his pledge. He admitted that he had made some mistakes in the early years. But then he quoted the famous line: “Better,” he said, “the occasional faults of a government guided by a spirit of charity and compassion than the constant omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.” As he was making his way up to the podium to that “Rendezvous with Destiny” speech, leaning on the arms of his son and a Secret Service agent, his braces locked in place to make it seem as if he could walk (he really could not on his own power), he reached over to shake the hand of a poet. He immediately lost his balance and fell to the floor, his braces unlocked, his speech sprawled about him. He said to the people around him, “Get me up in shape.” They dusted him off, picked him up almost like a rag doll, put his braces back in place, and helped him up to the podium. He then somehow managed to deliver that extraordinary speech.

There weren’t that many fireside chats:

He delivered only thirty fireside chats in his entire twelve years as president, which meant only two or three a year. He understood something our modern presidents do not: that less is more, and that if you go before the public only when you have something dramatic to say, something they need to hear, they will listen. Indeed, over 80 percent of the adult radio audience consistently listened to his fireside chats.

FDR truly swayed public opinion towards what he wanted:

And somehow, through his ability to communicate, he educated and molded public opinion. At the start of this process, the people were wholly against the idea of any involvement with Britain. By the time the debate finished in the Congress and the Lend-Lease Act was passed, the majority opinion in the country was for the lend-lease program. That is what presidential leadership should and must be about. Not reflecting public opinion polls, taking focus groups to figure out what the people are thinking at that moment, and then simply telling them what they’re thinking, but rather moving the nation forward to where you believe its collective energy needs to go.

Life in the FDR White House during WWII:

He became a part of an intimate circle of friends who were also living in the family quarters of the White House during the war, including Franklin’s secretary, Missy Lehand, who had started working for him in 1920, loved him the rest of her life, and was his hostess when Eleanor was on the road; Franklin’s closest adviser, Harry Hopkins, who came one night for dinner, slept over, and didn’t leave until the war was coming to an end; Eleanor’s closest friend, a former reporter named Lorena Hickock; and a beautiful princess from Norway, in exile in America during the war, who visited on the weekends.

Michael Beschloss on Eisenhower:

To hold down the arms race as much as possible, he worked out a wonderful tacit agreement with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev wanted to build up his economy. He didn’t want to spend a lot of money on the Soviet military because he wanted to start feeding people and recover from the devastation of World War II. But he knew that to cover this he would have to give speeches in public that said quite the opposite. So Khrushchev would deliver himself of such memorable lines as, “We Soviets are cranking out missiles like sausages, and we will bury you because our defense structure is pulling ahead of the United States.” Eisenhower dealt with this much as an adult deals with a small boy who is lightly punching him in the stomach. He figured that leaving Khrushchev’s boasts unanswered was a pretty small price to pay if it meant that Khrushchev would not spend much money building up his military. The result was that the arms race was about as slow during the 1950s as it could have been, and Eisenhower was well on the way to creating an atmosphere of communication. Had the U-2 not fallen down in i960 and had the presidential campaign taken place in a more peaceful atmosphere, I think you would have seen John Kennedy and Richard Nixon competing on the basis of who could increase the opening to the Soviets that Eisenhower had created.

Eisenhower pursued almost an opposite strategy to Reagan re: the USSR.

On one of the tapes LBJ made of his private conversations as president, you hear Johnson in 1964. He knows that the key to getting his civil rights bill passed will be Everett Dirksen of Illinois, Republican leader of the Senate. He calls Dirksen, whom he’s known for twenty years, and essentially says, “Ev, I know you have some doubts about this bill, but if you decide to support it, a hundred years from now every American schoolchild will know two names—Abraham Lincoln and Everett Dirksen.” Dirksen liked the sound of that.

I don’t think that worked. I’ll quiz the next American schoolchild I encounter.

On JFK:

What’s more, he had been seeking the presidency for so long that he had only vague instincts about where he wanted to take the country. He did want to do something in civil rights. In the i960 campaign, he promised to end discrimination “with the stroke of a pen.” On health care, education, the minimum wage, and other social issues, he was a mainstream Democrat. He hoped to get the country through eight years without a nuclear holocaust and to improve things with the Soviets, if possible. He wanted a nuclear test ban treaty.

Bay of Pigs:

People at the time often said Eisenhower was responsible for the Bay of Pigs, since it was Eisenhower’s plan to take Cuba back from Castro. I think that has a hard time surviving scrutiny. Eisenhower would not necessarily have approved the invasion’s going forward, and he would not necessarily have run it the same way. His son once asked him, “Is there a possibility that if you had been president, the Bay of Pigs would have happened?” Ike reminded him of Normandy and said, “I don’t run no bad invasions.”

Then Robert Caro comes to the plate with some classics:

Trying to understand why this relationship developed, I asked some of Roosevelt’s assistants. One of them, Jim Rowe, said to me, ‘You have to understand: Franklin Roosevelt was a political genius. When he talked about politics, he was talking at a level at which very few people could follow him and understand what he was really saying. But from the first time that Roosevelt talked to Lyndon Johnson, he saw that Johnson understood everything]! ^ was talking about.”

This young congressman may have been unsophisticated about some things, but about politics—about power—he was sophisticated enough at that early age to understand one of the great masters. Roosevelt was so impressed, in fact, that once he said to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, “That’s the kind of uninhibited young politician I might have been—if only I hadn’t gone to Harvard.” Roosevelt made a prediction, also to Ickes. He said, ‘You know, in the next generation or two, the balance of power in the United States is going to shift to the South and West, and this kid, Lyndon Johnson, could be the first southern president.”

Hill Country:

It was also hard for me to understand the terrible poverty in the Hill Country. There was no money in Johnson City. One of Lyndon’s best friends once carried a dozen eggs to Marble Falls, 22 miles over the hills. He had to ride very slowly so they wouldn’t break; he carried them in a box in front of him. The ride took all day. And for those eggs he received one dime.

Hill Country women:

asked these women—elderly now—what life had been like without electricity. They would say, “Well, you’re a city boy. You don’t know how heavy a bucket of water is, do you?” The wells were now unused and covered with boards, but they would push the boards aside. They’d get out an old bucket, often with the rope still attached, and they’d drop it down in the well and say, “Now, pull it up.” And of course it was very heavy. They would show me how they put the rope over the windlass and then over their shoulders. They would throw the whole weight of their bodies into it, pulling it step by step while leaning so far that they were almost horizontal. And these farm wives had yokes like cattle yokes so they could carry two buckets ofwateratatime. They would say, “Do you see how round-shouldered I am? Do you see how bent I am?” Now in fact I had noticed that these women, who were in their sixties or seventies, did seem more stooped than city women of the same age, but I hadn’t understood why. One woman said to me, “I swore I wouldn’t be bent like my mother, and then I got married, and the babies came, and I had to start bringing in the water, and I knew I would look exactly like my mother.”

LBJ effectively nagged FDR until he got a dam built and then transmission lines extended that would electrify Hill Country:

This one man had changed the lives of 200,000 people. He brought them into the twentieth century. I understood what Tommy Corcoran meant when he said, “That kid was the best congressman for a district that ever was.”

Ben Bradlee on Nixon:

When he was detached, Nixon could see with great subtlety the implication of actions. The story about Chicago mayor Richard Daley delivering enough graveyard votes for Kennedy to win one of the narrowest victories in the history of presidential politics is well known. Some say that Nixon made a very statesmanlike, unselfish decision in not protesting voting irregularities. He felt, they suggest, that it could weaken the country to have no one clearly in charge while the dispute went on. But as someone who covered the story closely—I was the reporter who quoted Daley’s remark to JFK on election night: “With a little luck and the help of a few close friends, we’re gonna win. We’re gonna take Illinois”—I am not so sure of Nixon’s altruism. What actually happened was this: Nixon sent William P. Rogers, who would later become his attorney general, to check on the situation. Rogers reported back that however many votes were cast illegally by Democrats in Chicago and Cook County, just as many were probably cast illegally by Republicans in downstate Illinois. I am almost certain that Nixon would have found it irresistible to protest the illegal votes had it not been for the fact that his own party might have been doing the same thing. He made a political decision: The risk was too great. He certainly had the power to protest, but for not entirely statesmanlike reasons chose not to use it.

Edmund Morris in his lecture gives some of the clearest takes on Reagan I’ve seen him deliver:

In the last weeks of 1988, toward the end of his presidency, he let me spend two complete days with him. I dogged his footsteps from the moment he stepped out of the elevator in the morning till the moment he went back upstairs. Within hours I was a basket case, simply because I discovered that to be a president, even just to stand behind him and watch him deal with everything that comes toward him, is to be constantly besieged by supplications, emotional challenges, problems, catastrophes, whines. For example, that first morning I’m waiting outside the elevator in the White House with his personal aide, Jim Kuhn. The doors open, out comes Ronald Reagan giving off waves of cologne, looking as usual like a million bucks, and Jim says to him, “Well, Mr. President, your first appointment this morning is going to be a Louisiana state trooper. You’re going to be meeting him as we go through the Conservatory en route to the Oval Office. This guy had his eyes shot out in the course of duty a year ago. He’s here to receive an award from you and get photographed, and he’s brought his wife and his daughter. You’ll have to spend a few minutes with him, just a grip-and-grin, and then we’re going on to your senior staff meeting.” So around the corner we go, and I’m following behind Reagan’s well-tailored back, and there is this state trooper, eyes shot out, aware of the fact that the president is coming—he could hear our footsteps. And there’s his wife, coruscating with happiness. It’s the biggest moment of their lives. There, too, is their little girl. Reagan walks up, introduces himself to the trooper, gives him the double handshake—the hand over the hand, the magic touch of flesh—and expertly turns him so the guy understands they are going to be photographed. The photograph is taken, a nice word or two is exchanged with his wife. It lasted about thirty-five seconds. On to the Oval Office. By the way, Reagan said to me as we walked along, ‘You know the biblical saying about an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth? I sure would like to get both eyes of the bastard that shot that policeman.” In other words, he was as moved as I was. But he had magnificently concealed it. A president has to deal with this kind of thing all day, every day, for four or eight years. He therefore has to be the kind of person who is expert at controlling emotion, at not showing too much of it—containing himself; otherwise, he is going to be sucked dry in no time at all and lose his ability to function in public.

(Also an origin story to why he wrote about Theodore Roosevelt:)

Theodore Roosevelt was also a man of overwhelming force—a cutter-down of trees in the metaphorical sense. He was famously aggressive. There was nothing he loved more than to decimate wildlife. I first became aware of him as a small boy in Kenya, when the city of Nairobi, where I was born, published its civic history. The book contained a photograph of this American president with a pith helmet and mustache and clicking teeth and spectacles. He had come to Kenya from the White House in 1910 and proceeded to shoot every living thing in the landscape. I remember as a ten-year-old boy looking at this picture of this man and, as small boys do, saying to myself, “He looks as though he is fun. I’d like to spend time with that guy.” I was conscious even as a child not only of the sweetness of his personality but of this feeling of force that a smudgy old photograph could not obscure.

Reagan’s voice: