How big is Iran compared to the United States?

Posted: June 18, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

It’s pretty big. It would stretch from Oregon to Texas.

(Move it around yourself).

I was reminded of this from Halberstam’s Best and the Brightest:

There were men who opposed the invasion or at the very least were uneasy with it, and to a degree, they were the same men who would later oppose the Vietnam commitment. One was General David M. Shoup, Commandant of the Marine Corps. When talk about invading Cuba was becoming fashionable, General Shoup did a remarkable display with maps. First he took an overlay of Cuba and placed it over the map of the United States. To everybody’s surprise, Cuba was not a small island along the lines of, say, Long Island at best. It was about 800 miles long and seemed to stretch from New York to Chicago. Then he took another overlay, with a red dot, and placed it over the map of Cuba. “What’s that?” someone asked him. “That, gentlemen, represents the size of the island of Tarawa,” said Shoup, who had won a Medal of Honor there, “and it took us three days and eighteen thousand Marines to take it.” He eventually became Kennedy’s favorite general.

from Shoup’s Wikipedia page:

On May, 14 1966, Shoup began publicly attacking the [Vietnam] policy in a speech delivered to community college students at Los Angeles Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, for their World Affairs Day:

I believe that if we had and would keep our dirty, bloody, dollar-soaked fingers out of the business of these nations so full of depressed, exploited people, they will arrive at a solution of their own—and if unfortunately their revolution must be of the violent type because the “haves” refuse to share with the “have-nots” by any peaceful method, at least what they get will be their own, and not the American style, which they above all don’t want crammed down their throats by Americans.

While yapping about Thucydides Trap did we forget Herodotus Trap (war w/Persia? No! Why?)

Good Press

Posted: June 18, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, everyone's a critic Leave a commentHaving a good press week:

New York Times, The Best TV Shows of 2025 So Far

Vulture, 119 Books Every Comedy Fan Should Read

Hollywood Reporter, Ten Best TV Shows of 2025

Vanity Fair, The Best TV Shows of 2025 So Far.

Alan Sepinwall writing in Rolling Stone

You know what? Showbiz is mostly heartbreak and failure so we’re gonna celebrate our wins around here.

Curfew

Posted: June 17, 2025 Filed under: France Leave a comment

LA mayor Karen Bass made the front page of Le Monde while we were in France, and gave us a chance to ponder the etymology of “curfew”

from Etymology Online:

curfew(n.)

early 14c., curfeu, “evening signal, ringing of a bell at a fixed hour” as a signal to extinguish fires and lights, from Anglo-French coeverfu (late 13c.), from Old French cuevrefeu, literally “cover fire” (Modern French couvre-feu), from cuevre, imperative of covrir “to cover” (see cover (v.)) + feu “fire” (see focus (n.)). Related: Curfew-bell (early 14c.).

The medieval practice of ringing a bell (usually at 8 or 9 p.m.) as an order to bank the hearths and prepare for sleep was to prevent conflagrations from untended fires. The modern extended sense of “periodic restriction of movement” had evolved by 1800s.

They can’t give this thing away!

Posted: June 3, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

Back in 2021 we reported on Platt National Park/Chickasaw National Recreation area, which as far as I know is the only national park ever to be downgraded. We even had a chance to visit. The nature there has been heavily altered by human hand, it’s almost a crafted landscape. That’s not usually how we now like to think of or act in our national parks.

Yesterday in Bloomberg:

mentions the former Platt NP:

Republican Representative Tom Cole of Oklahoma has offered Chickasaw National Recreation Area in Oklahoma as a candidate to be transferred to the Chickasaw Nation, which sold it to the federal government in 1902. Congress turned it into Platt National Park, until it stripped the park of “crown jewel” status and changed its name in 1976.

Today, the park service spends about $4.5 million to accommodate more than 1.5 million annual visitors at Chickasaw NRA.

Cole’s office said the Chickasaw Nation hasn’t asked for the recreation area to be returned, but the nation’s governor, Bill Anoatubby, said in a statement that it’s interested.

So far, though, there’s little other interest in transfers.

Sure, why not?

Worth remembering how we got here though:

In some cases, the National Park Service was put in charge of some areas because residents didn’t trust the states to manage them.

That’s what happened at Big Cypress, which became the first national preserve in 1974. Congress agreed with many south Floridians that the Rhode Island-sized wetland needed to be protected from the state’s plan to build what would have been the world’s largest commercial airport.

Floridians “wanted to protect it and they didn’t trust the state,” McAliley said. “People wanted the Park Service because they trusted them to manage natural qualities.”

Jedediah Smith Lunch

Posted: May 31, 2025 Filed under: the American West, the California Condition Leave a comment

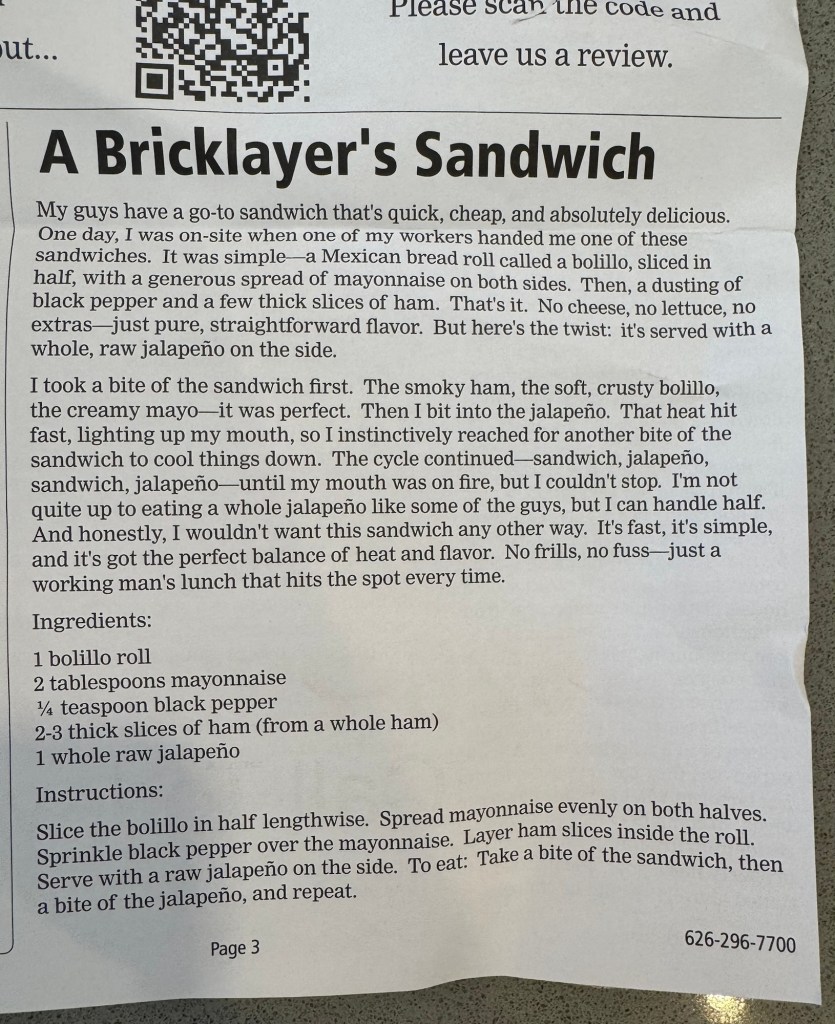

Thinking of hosting an event where we eat the lunch Jedediah Smith has at the San Gabriel mission, California around November 7 in 1826:

At 11 O Clock [am] the Father came and invited us to dinner. We accompanied him to the office adjoining the dining room and after taking a glass of Gin and some bread and cheese we seated ourselves at the table which was furnished with Mutton Beef Chickens Potatoes Beans and Peas cooked in different ways. Wine in abundance made our reverend fathers appeared to me quite merry.

Gin, bread, cheese, mutton, beef, chicken, potatoes, beans, peas, wine in abundance, at eleven in the morning. (In fairness Jed has been up since sunup).

Smith notes that he enjoyed his meals at San Gabriel because it had been a long time since he’d sat at a table (he’d come overland through the Rockies and across the Mojave Desert). His first view of the mission:

Arrived in view of a building of ancient and castle-like appearance.

(from Wikipedia)

At that time what Smith calls “the village of the angels” was a minor outlying place. Smith records that the people of the village of the angels were master horsemen, and he describes their method. Those sensitive to animal suffering may wish to skip:

My guide informed me that the inhabitants of the village and of the vicinity collect whenever they consider the country overstocked and build a large and strong pen with a small entrance and two wings extending from the entrance some distance to the right and left. Then mounting their swiftest horses they scour the country and surrounding large bands they drive them into the enclosure by hundreds. They will there perhaps Larse a few of the handsomest and take them out of the pack. A horse selected in this manner is immediately thrown down and altered blindfolded saddled and haltered (for the Californians always commenc with the halter). The horse is then allowed to get up and a man is mounted. when he is firmly fixed in his seat and the halter in his hand an assistant takes off the blind the several men on horseback with handkerchiefs to frighten and some with whips to whip raise the yell and away they go. The poor horse having been so severely punished and frightened does not think of founcing but dashes off at no slow rate for a trial of his speed. After running until he is exhausted and finding he cannot get rid of his enemies he gives up. He is then kept tied for 2 or 3 days saddled and rode occasionally and if he proves docile he is tied by the neck to a tame horse until he becomes attached to the company and then turned Loose. But if a horse from the moment he is taken from the pen proves refractory they do not trouble themselves with him long but release him from his bondage by thrusting a knife to his heart. Cruel as this fate may seem it is a mercy compared to that of the hundreds left in the pack for they are shut up to die a death most lingering and most horrible, enclosed within a narrow space without the possibility of escape and without a morsel to eat they gradually loose their strength and sink to the ground making at time vain efforts to regain their feet and when at last all powerful hunger has left them but the strength to raise their heads from the dust with which they are soon to mingle: their eyes that are becoming dim with the approach of death may catch a glimpse of green and wide spread pastures and winding streams while they are perishing from want. one by one they die and at length the last and most powerful sinks down among his companions to the plain. No man of feeling can think of such a scene without surprise indignation and pity. Pity for the noblest of animals dying from want in the midst of fertile fields. Indignation and surprise that men are so barbarous and unfeeling. A fact so disgraceful to the Californians was not credited from a single narrator but has since been corroborated.

Perhaps worth considering here that Smith was writing in a tradition of Anglo/Protestant anti-Spanishism. Still. I’m prepared to believe Los Angeles has some history of horse crime to answer for.

The real center of power at this time, where Jedediah is eventually sent to answer to the governor, is San Diego. Smith says San Diego is “much decayed.” In a footnote, editor George R. Brooks says:

Smith was not alone in his opinion that things at San Diego were somewhat rundown. “Of all the places we had visited since our coming to California, excepting San Pedro, which is entirely deserted, the presidio at San Diego was the saddest. It is built on the slope of a barren hill, and has no regular form; it is a collection of houses whose appearance is made still more gloomy by the dark color of the bricks, roughly made, of which they are built.

The fine appearance of [the mission] loses much on nearing it; because the buildings, though well arranged, are low and badly kept up. A digusting slovenliness prevails in the padres’ dwelling.” (Carter, “Duhaut-Cilly,” 218-19).

Smith’s memoir has an interesting backstory, it’s a “found in an attic a hundred years later” kinda tale. My edition was published in 1977. I wonder if Cormac McCarthy had this at hand when writing the San Diego parts of Blood Meridian. I betcha he did.

Savoy Special (and knowing and not in the age of AI)

Posted: May 30, 2025 Filed under: beer, Chicago Leave a comment

My friend Raj is an investor. It’s fair to say he’s passionate about finding material on Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett. In following this passion he came across my writing on Munger. He lives here in Southern California, we corresponded then met up, became friends IRL. He sends me items of interest about Buffett and Munger and related characters.

The other day he sent me a 1993 NYT profile of Herbert Allen, he of the Sun Valley conference. This detail caught my attention:

Over the past year, Mr. Allen has also led a $400 million financing drive, with his company a big investor, to help Victor Kaufman, former head of Columbia Pictures, begin a new studio, Savoy Pictures Entertainment. In October, Savoy will release the first of a dozen films (“A Bronx Tale,” Robert De Niro’s first effort as director) in a bid to succeed where M-G-M, Carolco and Orion have not.

Regular readers of Helytimes will know Savoy’s been on our mind. We hope to soon be traveling back there.

The word Savoy, via the London neighborhood where several nobles from there nine hundred years ago -> famous hotel -> Harlem ballroom, a big band hit, etc came to be associated with elegance, fanciness, a good meal, a good time.

So this caught my eye. Savoy Pictures.

(Their record was mixed.)

Where did Savoy Pictures get its name? From Wikipedia I learn:

Kaufman has claimed that the name came from the Savoy Special bat Robert Redford‘s character used in The Natural.[1]

Aha. In the novel and movie, there’s a character, Bobby Savoy, a batboy.

Was there a meaning ascribed to this name? I decide to plug the question into Perplexity AI. In three seconds it produces a decent-seeming report. This caught my eye:

Cultural Reference:

• There is also a real-world reference: “Savoy Special” was a brand of beer in the 1930s, made by the United States Brewing Company. However, within the context of the film and novel, the naming is primarily a nod to Bobby Savoy, and there is no explicit explanation in the narrative that connects the bat’s name to the beer brand.

Interesting! I ask Perplexity about the history of Savoy Special. The answer is unsatisfying, mostly citing auctions for vintage cans. I ask ChatGPT and Claude. They give me a nugget or two:

Savoy Special Beer was a product of the Savoy Brewing Company, based in Chicago, Illinois. Evidence of its existence includes a 12-ounce flat-top can from 1960, which was manufactured by the American Can Company and featured their “Keglined” technology—a method designed to prevent the beer from interacting with the metal can, thereby preserving its flavor. This particular can was recently listed for auction, indicating its status as a collectible item among vintage beer enthusiasts.

Finally I ask DeepSeek. In two seconds a what looks like a deep and thorough report:

Origins & Early Years**

- The Savoy Brewing Company was founded in 1881 by John Koehn, a German immigrant, and originally named Koehn Brewing Company.

- It was later renamed Savoy Brewing Co. (after the Savoy Hotel, which Koehn owned) and became known for its Savoy Special beer.

- The brewery was located at 18th & Lydia Avenue in Kansas City.

I follow up with a question about sources:

Primary Sources & References**

- “The Breweries of Kansas City: An Informal History” (1998) – Thomas M. Spencer

- Discusses the history of Savoy Brewing Co. and its founder, John Koehn, who also owned the Savoy Hotel.

- Notes that the brewery was renamed after the hotel.

I look into this book on Google. It doesn’t appear to exist? I ask DeepSeek: can we just doublecheck?

“Yup, sorry, made that up.” It hallucinated a book.

I press on, and DeepSeek does seem to find some verified deep cuts:

Did this robot train on The Kansas City Star archives? Maybe, or it’s yanking those citations from one of the books it cites that DOES exist: Kansas City Beer: A History of Brewing in the Heartland (2012) by Pete Dulin.

Missouri’s Breweries: 1800–2000 (2019) by Henry Herbst, Don Roussin, & Kevin Kious, while close to some things that may exist, appears to be another hallucination.

There’s a pretty thorough-seeming history of the Savoy Hotel of Kansas City here, and it doesn’t mention beer or Koehn.

I get myself a Kindle edition of Kansas City Beer, and find the word Savoy does not exist in the text.

DeepSeek nonetheless insists on this June 12, 1904 ad in The Kansas City Star. But I track that down: also doesn’t appear to exist:

We enter a strange information landscape. What will be known? What can we count on? What’s reliable? It’s always been a question. But it’s extremely eerie to have robots that produce so much information that’s so close to being accurate. It seems like it could be accurate, but it’s not. And this is a computer, why isn’t it double-checking its own work? This is a case of “not even wrong.” It’s very unsettling, I don’t like it. Plus I’m out $12 for a Kindle of Kansas City Beer. I’ll write that off as a research expense.

The closest I can get to seemingly human-checked information is this Tavern Trove citation that the United States Brewing Company of Chicago produced Savoy Special beer from 1932-1951.

We can see right on the can that Savoy Special was produced by Atlantic Brewing Company, perhaps picking up where United States Brewing left off. Tavern Trove confirms this as well. There may be someone out there who remembers drinking this beer, even helped make it – do reach out on the comments – but our search will end here.

Can any historical truth be more knowable than the text on an old can, a solid archaeological object?

As for Savoy, they could’ve gotten the name from anywhere. There’s a Savoy, Illinois, apparently named in honor of a visit from Princess Maria Clotilde:

The Princess spent some time in exile in Prangins:

which would have been part of the historical Savoy before it ended up in Vaud, a canton of Switzerland. (Source)

How far can we go back on the word “Savoy”? From a footnote in The Fall of the House of Savoy by Robert Katz:

Savoy itself becomes known to us for the first time in the fourth century A.D. through the eyes of that wandering Roman historian Amaianus Marcellinus. Describing the tortuous course of the Rhone as it issues from Lake Geneva, Amaianus wrote that “without losing any of its majesty, it flows through Sapaudia and the land of the Sequani. • . .Sapaudia, or Sabaudia, is what we call Savoy, a word whoseorigins are somewhat obscure. One school traces it to Sapp-Wann, Celtic for “the land where the pine trees grow”; another to Sapp-Aud, “the land of the many waters.” But fourteenth-century Savoyard princes, apparently unsatisfied with such pacific and pastoral images, made their Savoy originate from Salva via (“save the way”), which held fast for centuries, although it was, presumably unwittingly, close to the roots of savage. Such etymological fictions and, as we will see, genealogical fables as well, helped to saturate the generations with a sense of mission and hold them steady on the course of aggression.

(You can maybe see why this book was not a bestseller?)

That’s in a book, the book was written by a human, a man with a reputation who put his name on it. Is it more trustworthy than the AI? I’d say so.

One thing I know: I’d love to crack open a cold Savoy Special in the kegliner can. That’s a feeling the AI can never really understand.

What more is there to know?

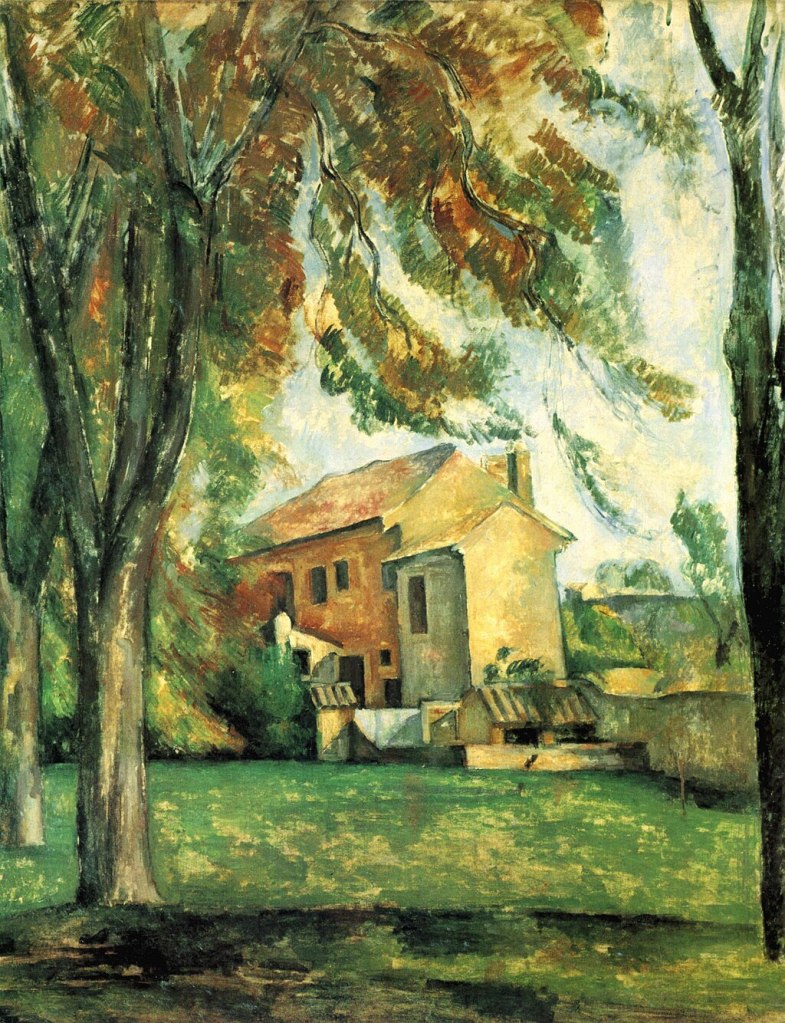

The Lac d’Annecy by Paul Cezanne

Posted: May 24, 2025 Filed under: art history Leave a comment

Cézanne painted this work while on holiday in the Haute-Savoie in 1896, writing dismissively of the conventional beauty of the landscape as “a little like we’ve been taught to see it in the albums of young lady travellers”. He rejected such conventions, seeking not to replicate the superficial appearance of the landscape but to express what he described as a “harmony parallel with nature” through a new language of painting.

In his essay “Cezanne’s Doubt” (mentioned by Jameson in Years of Theory) Maurice Merleau-Ponty says:

We live in the midst of man-made objects, among tools, in houses, streets, cities, and most of the time we see them only through the human actions which put them to use. We become used to thinking that all of this exists necessarily and unshakably. Cezanne’s painting suspends these habits of thought and reveals the base of inhuman nature upon which man has installed himself. This is why Cezanne’s people are strange, as if viewed by a creature of another species. Nature itself is stripped of the attributes which make it ready for animistic communions: there is no wind in the landscape, no movement on the Lac d’Annecy; the frozen objects hesitate as at the beginning of the world. It is an unfamiliar world in which one is uncomfortable and which forbids all human effusiveness. If one looks at the work of other painters after seeing Cezanne’s paintings, one feels somehow relaxed, just as conversations resumed after a period of mourning mask the absolute change and restore to the survivors their solidity. But indeed only a human being is capable of such a vision, which penetrates right to the root of things beneath the imposed order of humanity. All indications are that animals cannot look at things, cannot penetrate them in expectation of nothing but the truth. Emile Bernard’s statement that a realistic painter is only an ape is therefore precisely the opposite of the truth, and one sees how Cezanne was able to revive the classical

definition of art: man added to nature

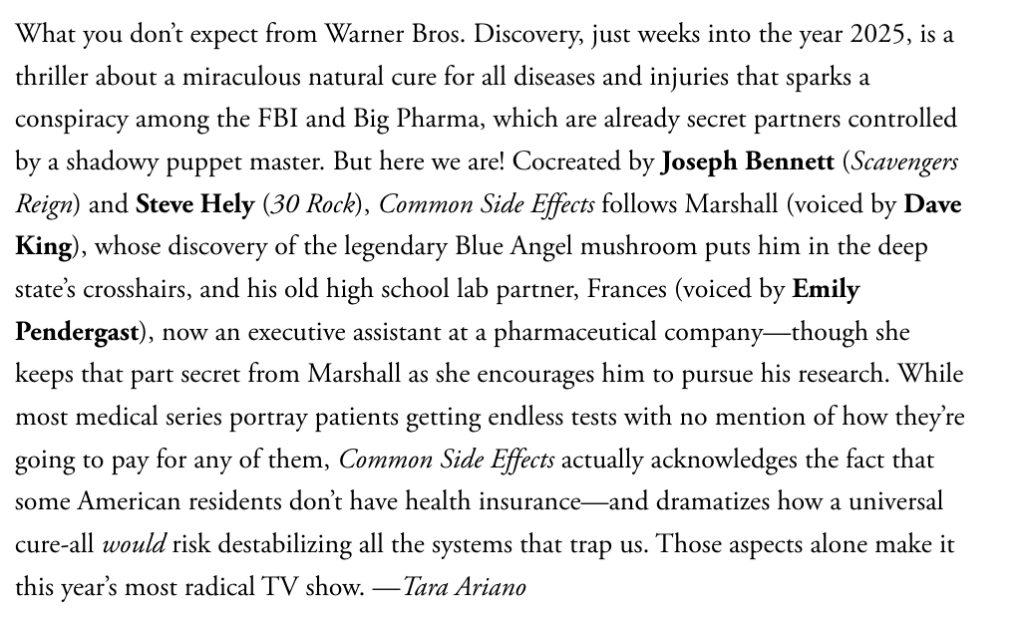

Looking into Annecy by Cezanne I also find this, La Barque ou Le Lac d’Annecy, which Christie’s sold for $403,200 USD

Here’s an intriguing essay by Jeffrey Meyers on Hemingway and Cezanne. In several places Hemingway said he wanted to write like Cezanne painted:

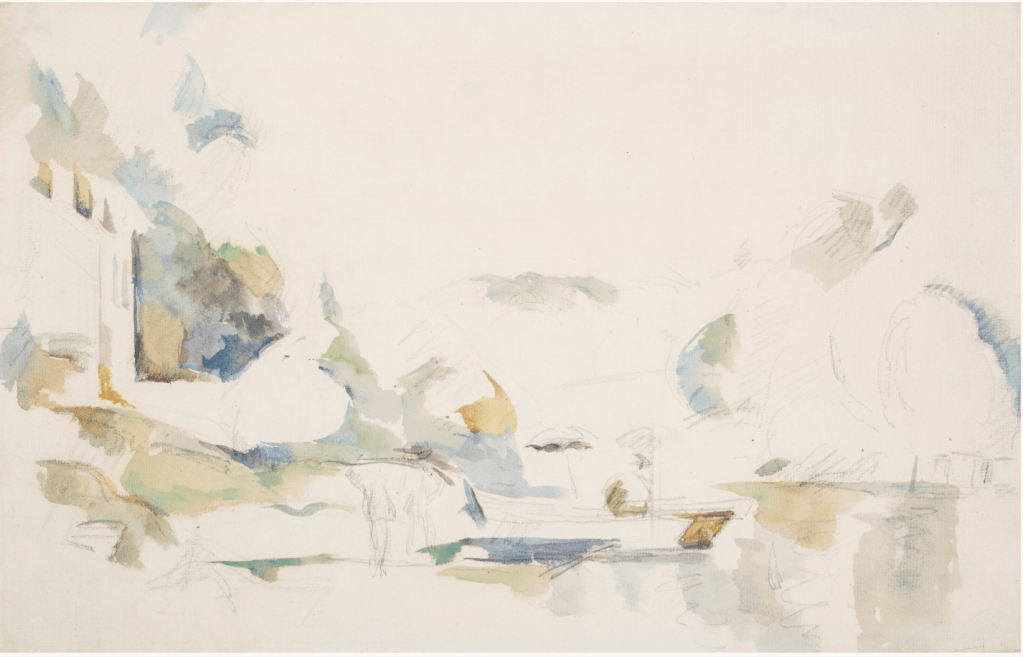

Hemingway spent several minutes looking at Cezanne’s “Rocks – Forest of Fontainebleu.” “This is what we try to do in writing, this and this, and the woods, and the rocks we have to climb over,” he said. “Cezanne is my painter, after the early painters. Wonder, wonder painter…

As we walked along, Hemingway said to me, “I can make a landscape like Mr. Paul Cezanne. I learned how to make a landscape from Mr. Paul Cezanne by walking through the Luxembourg Museum a thousand times with an empty gut, and I am pretty sure that if Mr. Paul was around, he would like the way I make them and be happy that I learned it from him.”

What does it mean to write like Cezanne painted? In his essay Merleau-Ponty quotes Cezanne in a way that gives a clue:

Nor did Cezanne neglect the physiognomy of objects and faces: he simply wanted to capture it emerging from the color. Painting a face “as an object” is not to strip it of its “thought.” “I agree that the painter must interpret it,” said Cezanne. “The painter is not an imbecile.” But this interpretation should not be a reflection distinct from the act of seeing. “If I paint all the little blues and all the little browns, I capture and convey his glance. Who gives a damn if they have any idea how one can sadden a mouth or make a cheek smile by wedding a shaded green to a red.” One’s personality is seen and grasped in one’s glance, which is, however, no more than a combination of colors. Other minds are given to us only as incarnate, as belonging to faces and gestures. Countering with the distinctions of soul and body, thought and vision is of no use here, for Cezanne returns to just that primordial experience from which these notions are derived and in which they are inseparable. The painter who conceptualizes and seeks the expression first misses the mystery— renewed every time we look at someone—of a person’s appearing in nature. In La peal de chagrin Balzac describes a “tablecloth white as a layer of fresh-fallen snow, upon which ,the place settings rose symmetrically, crowned with blond rolls.” “All through my youth,” said Cezanne, “I wanted to paint that, that tablecloth of fresh-fallen snow…. Now I know that one must only want to paint’rose, symmetrically, the place settings’ and ‘blond rolls.’ If I paint ‘crowned’ I’m done for, you understand? But if I really balance and shade my place settings and rolls as they are in nature, you can be sure the crowns, the snow and the whole shebang will be there.”

This effort did not make for an easy life for Cezanne:

Occasionally he would visit Paris, but when he ran into friends he would motion to them from a distance not to approach him. In 1903, after his pictures had begun to sell in Paris at twice the price of Monet’s and when young men like Joachim Gasquet and Emile Bernard came to see him and ask him questions, he unbent a little. But his fits of anger continued. (In Aix a child once hit him as he passed by; after that he could not bear any contact.)

…nine days out of ten all he saw around him was the wretchedness of his empirical life and of his unsuccessful attempts, the debris of an unknown celebrations

The closest Hemingway gets to saying something similar? Maybe it’s this, from an Esquire article, “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter,” October 1935, that’s in the form of a dialogue with an apprentice:

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise. Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Then get in somebody elseʼs head for a change If I bawl you out try to figure out what Iʼm thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Donʼt just think who is right. As a man things are as they should or shouldnʼt be. As a man you know who is right and who is wrong. You have to make decisions and enforce them. As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.

Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

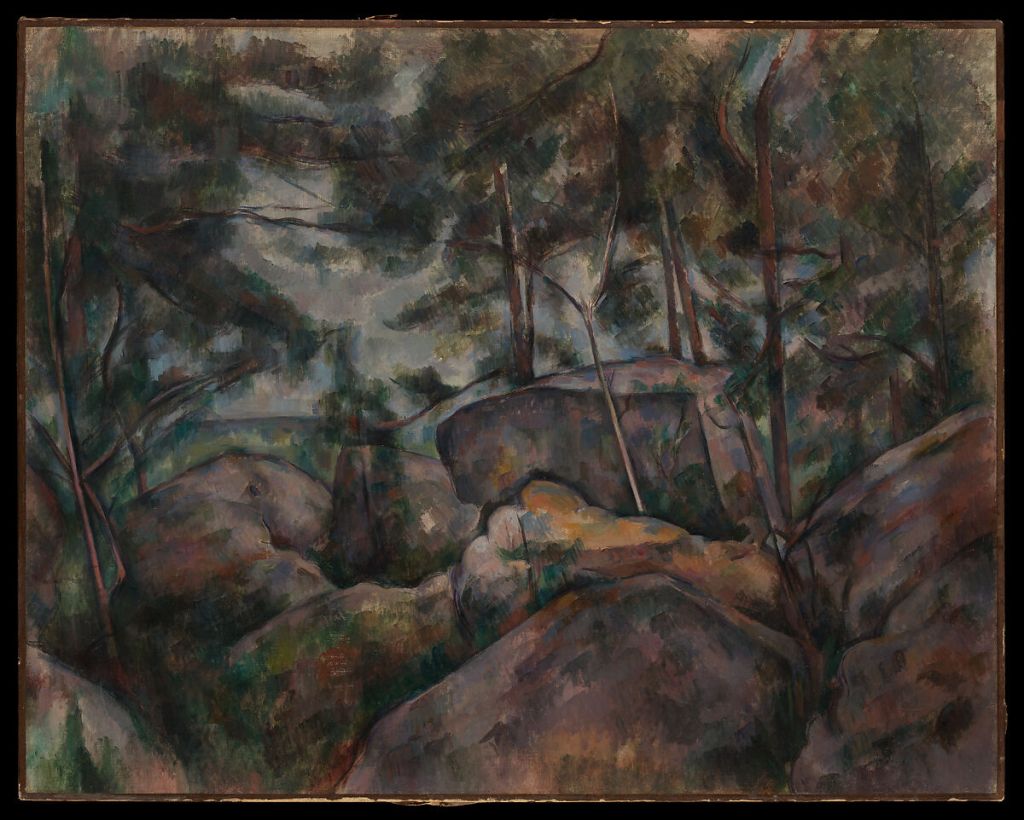

Cezanne left Annecy and went back to painting his Mont Saint-Victoire:

There are four Cezannes at the Norton Simon Museum, right down the street from where I’m typing this:

a couple at the Getty, one at the Hammer, and a classic at LACMA:

although that one’s not on display right now.

More on Cezanne.

Signs and wonders

Posted: May 23, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 CommentIt is a wonder to me that a human less than a year and a half old can identify all of these as “doggie.”

“Doggie.”

“Doggie!”

It’s enough to make me want to get a degree in semiotics from Brown University, or at least re-read Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud.

Can any other animal understand such abstract signs? The work on this veers towards ridiculous:

The monkeys chose between ‘tokens’ that represent actual foods. After choosing one of the two token options, monkeys could exchange their token with the corresponding food. What they saw was that the capuchin monkeys assigned a value for each token and food item. Capuchins were indifferent between one Cheerio and two pieces of parmesan cheese, indicating that the value of one Cheerio is equal to two times the value of one piece of parmesan cheese. When choosing between tokens that represented the same foods, the relative value increased – for example, capuchins were indifferent between one Cheerio-token and four parmesan-tokens.

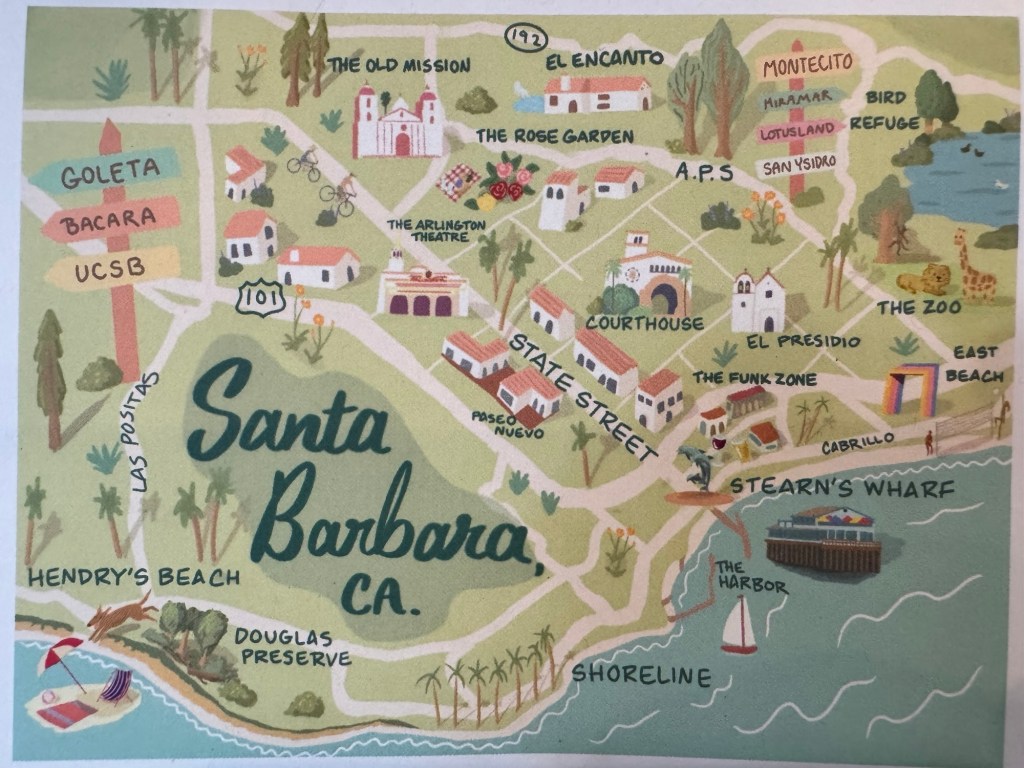

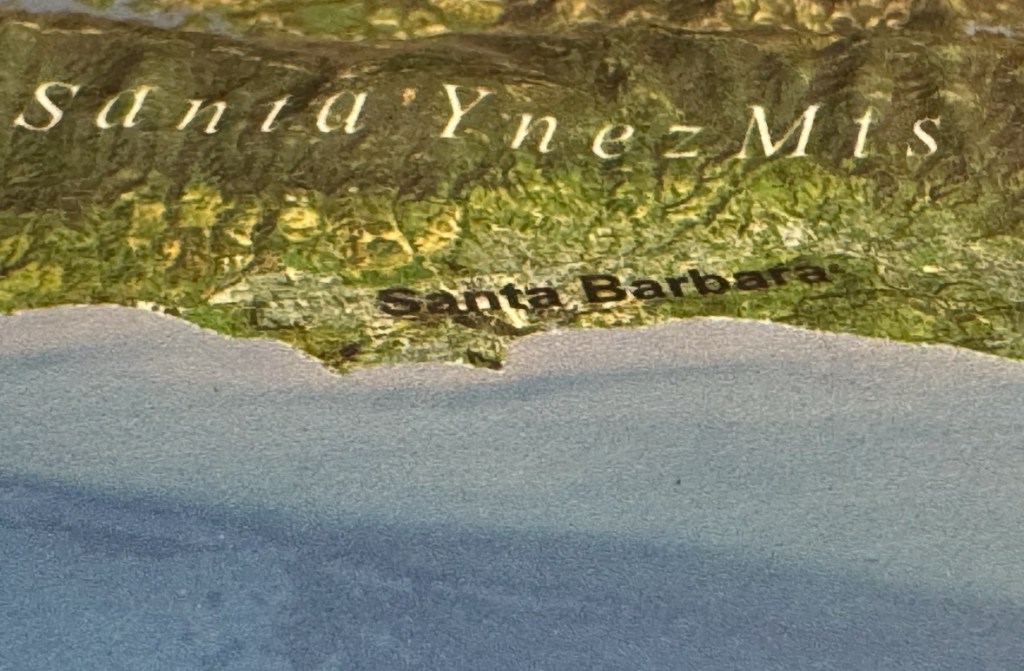

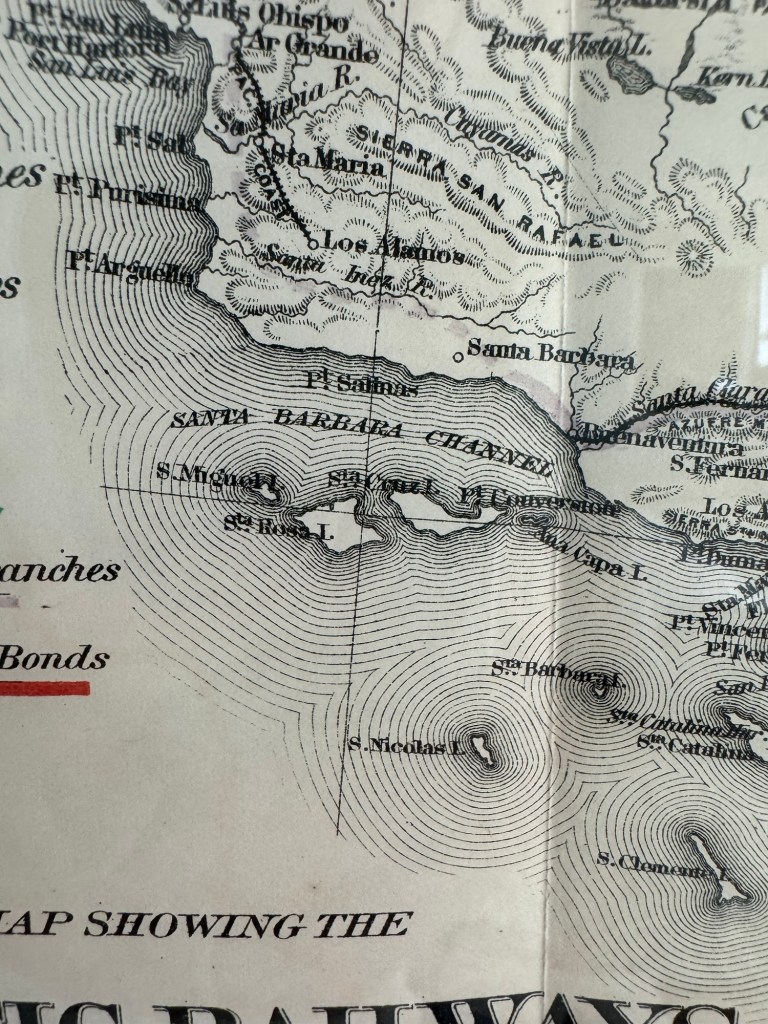

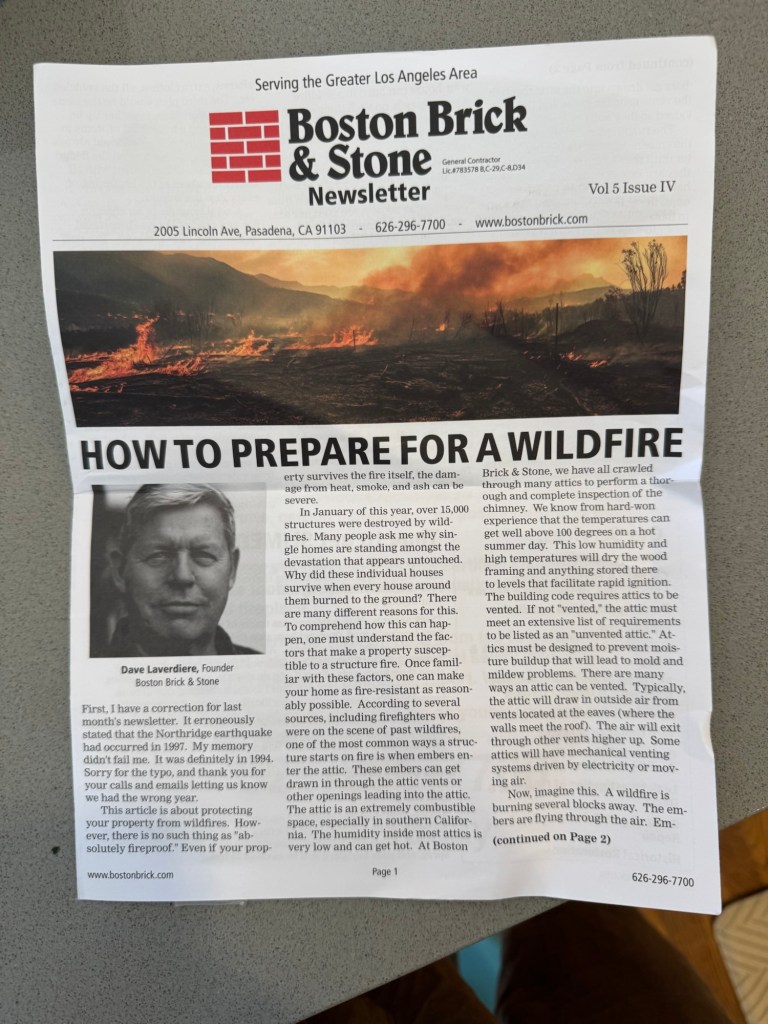

25.5 Hours (and three hundred years) in Santa Barbara (and Santa Barbara County)

Posted: May 18, 2025 Filed under: the California Condition 1 Comment(this is an excerpt from my book California Getaway, which will be published by Universiteit Utrecht Press in their Amerikaanse avonturenseries, spring 2029*)

Santa Barbara is divided by both the 101 Highway and the Union Pacific railroad tracks, shared by Amtrak, which run close together. This carves out an area squeezed along the waterfront called “the Funk Zone.” Funky in the sense of curious, unusual, quirky, and the funky taste and smell of unrefined wines. (Not funky in the sense of the African-American music genre: Santa Barbara is barely over 1% black. This may be part of why it was tolerated for there to be a restaurant named Sambo’s right on the beach until the year 2020).

In the Funk Zone a good place for sandwiches is Tamar.

The Coast Starlight bound for Seattle leaves grand, deco Union Station at 9:51am and pulls into Santa Barbara at 12:15pm. That’s assuming it’s on time, not a safe assumption, and assuming the tracks don’t get washed away by the waves. They’re awful close, one day it will happen. You’ll pass the industrial workings of LA, the Big Thunder Mountain country by Santa Susanna, then down into vegetable farms of almost obscene bounty, and then past the surf corner at Rincon, and the world’s safest beach at Carpinteria, and into Santa Barbara.

There’s always at least one college student, one European, and at least one mystery case on the long distance Amtraks.

Walkable, Mediterranean climate, remarkable architecture, a fishing port that’s also a farm market town, a collection point for the freshest produce and the wildest most experimental and interesting wines? Oh, it’s also a college town? The catch? The median home price is around two point five million dollars.

Welcome to Santa Barbara.

Mountains wall it on the north. On the south is the Santa Barbara Channel, shielded by the Channel Islands and full of fish and urchins. Squid is biggest catch, in dollars. The Chumash were feasting long here before the mission Spanish showed up driving herds of cattle. The archaeological riches found in what’s now Ambassador Park suggest that place was once a burial ground or a gathering place or both. (You hear the word “ceremonial” thrown around with the ancient peoples. What are our ceremonies? Going on vacation?)

The place was visited by Cabrillo and Vizcaino and who knows what other pirates and mariners before the mission was established in 1786. Richard Dana visited in 1834, went to a fandango, and was impressed, attracted, and repulsed by the exotic lifestyle of the rancheros. John Fremont’s expedition captured the city for the USA in 1846. The neat story about William Foxen leading him to the San Marcos Pass is repeated on a historical marker and in the WPA Guide, but the Santa Barbara historian Walker “Two Guns” Tompkins, who switched to history after writing a bunch of Westerns, says there’s no evidence of this. Imagine how remote Santa Barbara must’ve been from Mexico City by then.

In his Crown Journeys guide to New Orleans Roy Blount says,

I’ll bet I have been up in N. O. at every hour in every season

A good boast: he’s qualified.

I can’t make either claim about Santa Barbara. I suspect it’s pretty dead in the late to early hours. One day I’ll stay up all night and find out. Over about twenty years I have visited about 1.5 times a year.

On my first visits I found the town dramatic in geography but kinda sleepy. The big houses on the slopes were dramatic, and a wharf is always pleasing. If I stayed overnight I’d stay at one of the beach hotels and eat at Tupelo Junction or In n Out or La Super Rica, Julia Child’s favorite.

Long before many figured it out, [Julia Child] recognized that our pleasant climate, historical farming culture, and ranch-to-plate cuisine were conspiring together to elevate the American Riviera…

(source)

“The climate and the atmosphere [of Santa Barbara] recall the French Riviera between Marseille and Nice,” wrote Julia. “Very often, being there on the Riviera, where we used to have a little house, I’d… say, ‘Well, I’d just as soon be in Santa Barbara.’”

That from Edible Santa Barbara piece on JC. She actually lived in the next door woodsy microclimate of Montecito, which we’ll consider a separate topic.

Santa Barbara does have a touch of Julia Child about it: rich, pleasant, fancy, sorta stuffy? She retired there. A place to retire, if things went great.

But in the past few years on a couple visits to Santa Barbara I’ve seen two big changes that perk the place up, for the day tripper anyway. One is the Funk Zone Boom.

From a 2011 Santa Barbara Independent article on Funk Zone history by Ethan Stewart:

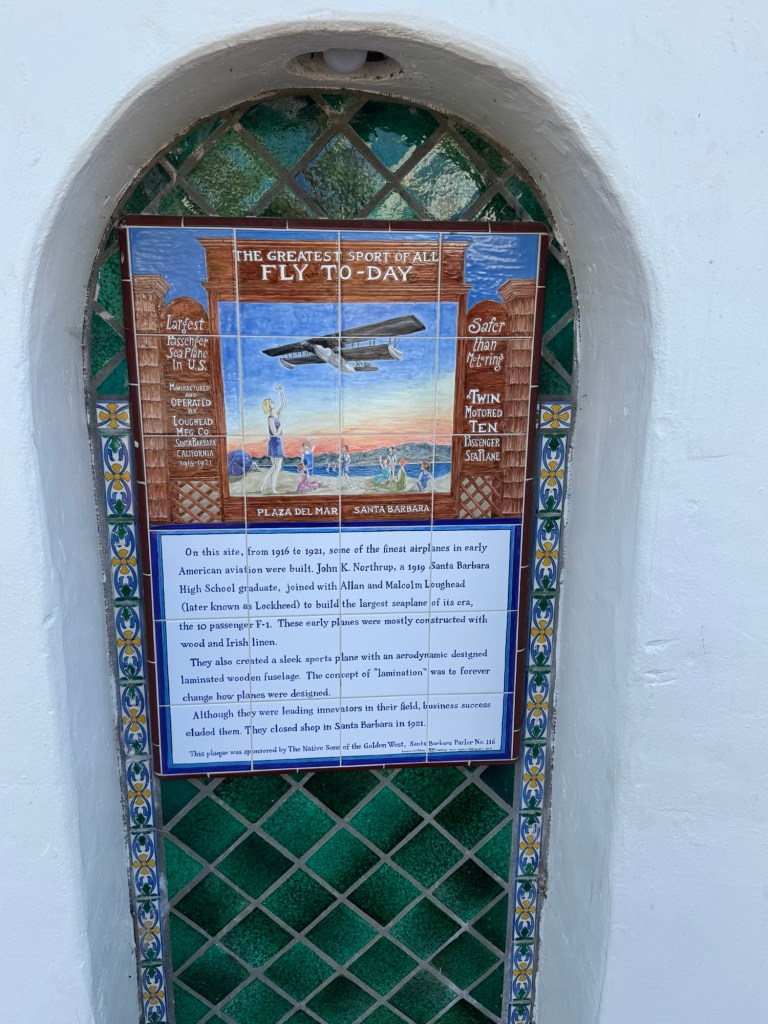

The Funk Zone was “funky” and functional long before the nickname was ever coined. In the mid 1900s and earlier, what we now call the Funk Zone was the industrial, marine, and manufacturing part of town. The Lockheed Corporation was born there, one of Santa Barbara’s first grain mills and feed stores was there (memorialized to this day by the tall, monolithic building at the ocean end of Gray Avenue), the Castagnolas used the area as ground zero for their fishing empire, and Radon Boats rose to prominence on Funk Zone soil, to name a few.

Activists, artists, and planners debated what to do with this area:

Controversial to this day, the city’s decision was ultimately to adopt a code that requires things in the Funk Zone to either be tourist-serving in nature, mixed-use residential/commercial units, or marine-oriented light manufacturing. In short, everything in the Funk Zone will eventually fall into one of these categories.

Fourteen years after that article, it appears that for better or worse the plan worked. The Funk Zone is less funky and strange than it used to be, and possibly worse for residents, especially those who don’t measure their riches in money. But for the tripper the Funk Zone is now full of wonderful places to consume. The multiple buildings of the Hotel Californian, mission style but built in 2025, dominate a block.

The other big change that perks up Santa Barbara came out of COVID: they closed down State Street to cars. Now there’s a walkable, bikeable avenue you can take from the wharf almost all the way to the mission.

Along the way you’ll pass some terrific buildings. Even the post office and the US Bankruptcy Court are magnificent.

Santa Barbara has progressed, yet in many respects the city of a hundred years ago foreshadowed the city of today. In 1842, Sir George Simpson, an English traveler, wrote: “Among the settlements, Santa Bárbara possessed the double advantage of being the oldest [sic] and the most aristocratic.” Few would rise to dispute that point today. The city still refrains from the commonplace. Her beaches and festivals never are vulgarized by catch-penny devices. Santa Barbara exemplifies the truth of the statement that life without beauty is but half lived.

Nowhere in the State has a higher standard been set and the achievements of this municipality are an incentive to city planners everywhere.

Santa Barbara is old. It was a native Canaliño village when the Spanish settled there, and as such, it was ancient even then. Superimposing European culture on the primitive Indian people was a hasty process, as historical time is reckoned. Where once existed the conical huts of the native Indians, now rise the urban structures of twentieth-century industry. Where once the campfires of Canaliños lighted the landscape at night, now blazing neon signs brighten the avenues of commerce. Where once natives stalked game in the underbrush, now chain-store clerks weigh out sliced meat behind delicatessen counters.

For Santa Barbara is as new as she is old. Preserving some of the most pleasant aspects of her Spanish traditions, reviving some of the customs of her earliest settlers, she is, nevertheless, as American as Council Bluffs, Iowa.

So says the 1941 WPA Guide to the city, which sums it up:

Santa Barbara’s chief business is simply being Santa Barbara.

Santa Barbara knew it had something special going on. The Harvard man turned California booster Charles Fletcher Lummis gave a speech, “Stand Fast Santa Barbara,” in 1923.

Beauty and sane sentiment are Good Business as well as good ethics. Carelessness, ugliness, blind materialism are Bad Business. The worst curse that could befall Santa Barbara would be the craze of GET BIG! Why big? Run down to Los Angeles for a few days — see that madhouse! You’d hate to live there!

…It is up to you to save Santa Barbara’s romance and save California’s romance for Santa Barbara. I would like to see Santa Barbara set her mark as the most beautiful, the most artistic, the most distinguished and the most famous little city on our Pacific Coast. It can be, if it will, for it has all the makings.“

Two years later, a big earthquake struck Santa Barbara:

The twin towers of Mission Santa Barbara collapsed, and eighty-five percent of the commercial buildings downtown were destroyed or badly damaged. A failed dam in the foothills released forty-five million gallons of water, and a gas company engineer became a hero when he shut off the city’s gas supply and prevented fires like those that destroyed San Francisco following the 1906 earthquake.

Perfect timing. The architects were ready: Lionel Pries, William Mooser, George Washington Smith. In the wake of the destruction the city’s Community Arts Association pushed the whole city to adopt rules for a unified architectural scheme. The strong willed Pearl Chase, born in Boston, seems like she was a key figure here. Chase Palm Park by the beach is named for her.

Pearl Chase: another Julia Child type?

If the earthquake had happened in 1915, or 1935, or 1945, I’m not sure the will would’ve been there to create such a Santa Fe-style strict code for unified building. Funny how history works out. Chance and random is absolutely an element, along with the forceful personalities. There’s a lesson here in never letting a good crisis go to waste. If there were a movement with a vision and a political will, LA could do something incredible with rebuilding Palisades and Altadena. Instead it seems we’re limping along directionless.

The result of the Santa Barbara revitalization is what you see and you see it everywhere. Santa Barbara is a theme park of itself. The Hotel Californian, where we stayed, was built in 2015, a new Funk Zone construction, but keeps to the white walls/red roof mission style aesthetic.

After lunch we tasted some wines at Kunin tasting room. Our pourer was knowledgable but not overbearing. He pointed out that Santa Barbara isn’t the biggest city in Santa Barbara County. That’s Santa Maria, with 109,987 residents. Santa Barbara, tucked in a corner of the county, has a mere 86,499, comparable to Elgin, Illinois or Newton, Massachusetts.

Santa Barbara isn’t very big, as California cities go. Here are some cities in California that have more people: Hemet, Manteca, Citrus Heights, Tracy, Norwalk, Hesperia, Rialto, Jurupa Valley, Menifee, Temecula, Thousand Oaks. Santa Barbara is #94 in the latest California city population rankings, just ahead of Lake Forest and Leandro. Think it’s fair to say that it punches above its weight in cultural resonance.

Santa Barbara County is vast: 2,745 square miles. If you smooshed down all the mountains and made it flat it would be even bigger. About a third of that is national forest. The population is small: 441,257 residents. Compare that to Norfolk County, MA, which has 727,473 over 441 square miles, and it doesn’t feel exactly crowded. Santa Barbara County thus is remote. Our wine server got to talking about the Santa Barbara Highlands region, where he said there are many beautiful vineyards, but no tasting rooms, and he recommended packing our own food.

After a siesta and a hot tub soak on the roof of the Californian, dinner was at Holdren’s. Cold martinis, cowboy steak, local red wine, brown leather booths, a classic. Pretty popping for a Tuesday. Sometime I’ll have to try the tasting menu at Barbareño, where the food is inspired by local history and tradition.

(Always funny to see a fishing boat leaving at like 9:15 am. Aren’t you supposed to be up at at ‘em?)

The next morning, after Helena Avenue Bakery (A+, bakery from a dream) treats we rode the janky hotel bikes up to the mission, just challenge enough along carless State Street with a brief residential detour. The ride’s uphill, revealing another feature of Santa Barbara. The city is tiled slightly to the south, opening to the ocean. This creates, in my opinion, the effect that Santa Barbara can seem “too sunny,” even though it has about the same number of sunny days as LA, and not infrequent Pacific fog. North of the equator the sun just hits harder when a place is south-facing.

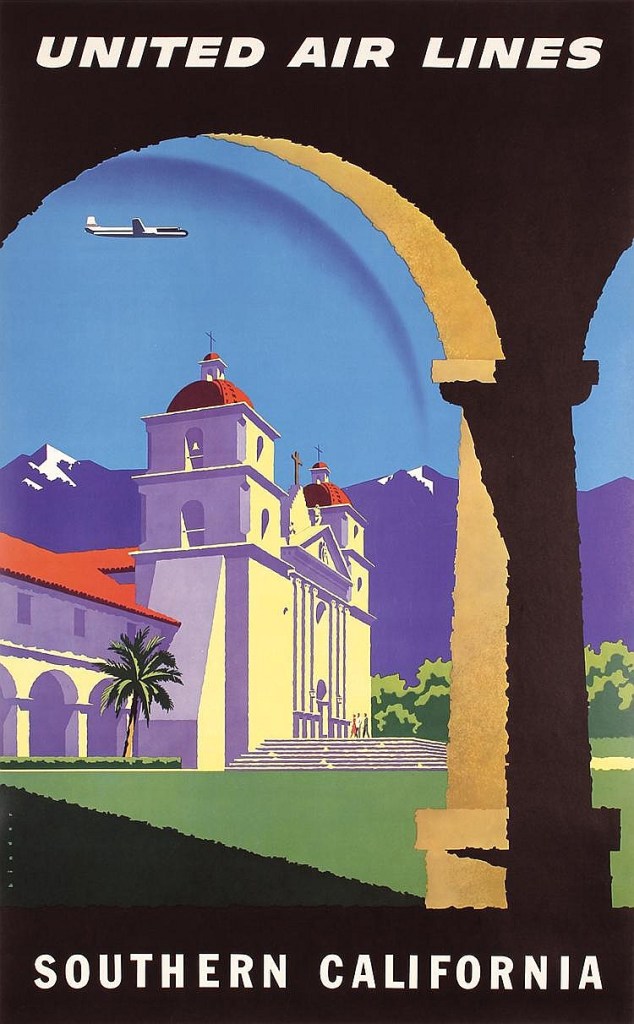

These days the mission and the mission period tends to be more associated with the word “genocide” and the crummy outcomes for Mission Indians rather than with romance and grandeur. It wasn’t that long ago they were a draw, consider this old United Airways poster:

That’s Queen of the Missions Santa Barbara right there, apparently circa 1952. These days I don’t think you sell California that way. “Old churches” are like the last thing you’d go see – you’re coming for Star Wars Land and $24 smoothies!

The rose garden is the star of the mission

and the old washing basin.

Then it’s downhill, along Garden Street, past the splendid five and six million dollar houses, maintained in style, and to Alice Keck Memorial Garden.

(Wikipedia’s Summerzz took that one.)

Alice Keck was the daughter of William Keck, a Daniel Plainview-grade oil man:

Starting as a penniless roustabout, he rose in the 1920s to found the Superior Oil Company. He pioneered deep offshore drilling, was first to find commercial deposits in the Gulf of Mexico, and practically ran the oil-rich nation of Venezuela. Even in his later years, when a drilling rig brought up a slimy core, old man Keck sniffed and tasted the rock to gauge the prospect.

another:

William Keck then became one of the first oilmen to move his business to Houston, which at the time was not much more than an inadequately drained malarial swamp… William Keck was known throughout the company he had created as “the Old Man”, and people called him that until the day he died. His character was strong and some said it was mean. His political views were fiercely conservative, but he was nimble and innovative when it came to doing business.

(sources for those. Who would guess a book about diamond spikes in the Canadian tundra would be quoted in an article about a California oil man?)

Mean or not, his name lives on in various charitable projects all over Southern California, like Keck Medicine at USC. His company Superior, was swallowed by Mobil which was swallowed by Exxon.

As you cruise down and look out over the water, you can still see oil wells in the Channel. Some of them are in various states of being dismantled, which is a whole project.

Both Northrop and Lockheed/Loughead were from here? Too big, topic for another day. Were I Pynchon I’d stop here and spend ten years on a 700 page novel about how Santa Barbara is a node of post-Cold War evil?

Before our return we scored some burritos for the train at IV Food Co-Op Downtown Market, and took some oysters and a dry white wine at Bluewater Grill. The server there, from Alabama, used to work in Taos, and gave me some ski reports from across the Rocky Mountain West. She seemed to be part of the class of lovely young people who turn up working at the affluent resort towns of the world. While in Bolivia I met a Chilean who said he’d spent a year in Santa Barbara. “What were you doing,” I asked, “studying?” “No,” he said, “just surfing and skating.” Santa Barbara seems like Heaven for that, if you can make the numbers math out. You’d probably have to live over in the student ghetto lands of Isla Vista, which is arguably a slum, but in a sorta student flophouse way. I have explored over there, though not on this trip, there is indeed something grim about it, but that’s not true Santa Barbara, and not what we’re talking about today.

Geneva’s the only person I know who grew up in Santa Barbara, and whatever she gets paid to write these days we can’t afford it! So we’ll have to do without firsthand accounts from native Santa Barbareños.

With that we were at the old Southern Pacific station for the 1:45pm Pacific Surfliner back to Los Angeles, refreshed and tired, energized and inspired.

This is just the daytripper’s view of Santa Barbara. Someone could make the case I’m missing “the real Santa Barbara,” I’m sure I am. There was a fatal stabbing there the other day, for example. But that’s not what I’m into. I’m after what makes Santa Barbara Santa Barbara. I want to put the place in context for myself, and for you, and to make those 25 hours last a little longer.

The Found Image Press finds these old postcards and reprints them, but without any context, or dates

* fictional

Preakness

Posted: May 17, 2025 Filed under: horses Leave a commentIt’s Preakness Saturday – I like Journalism, the California local, but conditions at Pimlico today appear unspeakable so who knows – so I direct you to this post from 2021 on the origins of the race, and the original Preakness.

Have a blessed weekend!

David Souter

Posted: May 10, 2025 Filed under: Boston, New England Leave a comment

None of this [Washington eminence] held any appeal for David Souter, who after returning home from his Rhodes scholarship at Magdalen College, Oxford, crossed the Atlantic only once again, for a reunion there. Who needed Paris if you had Boston, he would remark to friends. When the court is in recess, he gets in his Volkswagen and heads to Weare, N.H., to the small farmhouse that was home to his parents and grandparents.

from a 2009 NYT consideration of Souter by Linda Greenhouse.

I remember reading that remark when I was a kid, maybe in Alex Beam’s column in The Boston Globe. I’ve sometimes thought that myself when back in Boston. Although I’m usually back in the spring or fall. I don’t think too many people think that in February.

When I look at my (rare) photographs I never seem to quite capture the magic.

A shy man who never married and who much preferred an evening alone with a good book to a night in the company of Washington insiders, Justice Souter retired at the unusually young age of 69 to return to his beloved home state.

We need more of this. I’m reading his obituary and Charles Grassley, who was at Souter’s confirmation hearing, is still a damn senator!

After he retired, Justice Souter sold the family farmhouse and moved to a home he bought in nearby Hopkinton. The reason, he explained, was his large book collection, which the old farmhouse could neither hold nor structurally support. Reading history remained a cherished pastime. “History,” he once explained, “provides an antidote to cynicism about the past.”

One of the best aspects of Boston is that it’s one big history book.

Across The River and Into The Trees, Ernest Hemingway (1950)

Posted: May 3, 2025 Filed under: Hemingway 4 Comments

The Colonel is talking to his driver, Jackson:

“That’s Torcello directly opposite us,” the Colonel pointed. “That’s where the people lived that were driven off the mainland by the Visigoths. They built that church you see there with the square tower. There were thirty thousand people lived there once and they built that church to honor their Lord and to worship him. Then, after they built it, the mouth of the Sile River silted up or a big flood changed it, and all that land we came through just now got flooded and started to breed mosquitoes and malaria hit them. They all started to die, so the elders got together and decided they should pull out to a healthy place that would be defensible with boats, and where the Visigoths and the Lombards and the other bandits couldn’t get at them, because these bandits had no sea-power. The Torcello boys were all great boatmen.

So they took the stones of all their houses in barges, like that one we just saw, and they built Venice.” He stopped. “Am I boring you, Jackson?”

“No, sir. I had no idea who pioneered Venice.”

“It was the boys from Torcello. They were very tough and they had very good taste in building. They came from a little place up the coast called Caorle. But they drew on all the people from the towns and the farms behind when the Visigoths over-ran them. It was a Torcello boy who was running arms into Alexandria, who located the body of St.

Mark and smuggled it out under a load of fresh pork so the infidel customs guards wouldn’t check him. This boy brought the remains of St. Mark to Venice, and he’s their patron saint and they have a cathedral there to him. But by that time, they were trading so far to the east that the architecture is pretty Byzantine for my taste. They never built any better than at the start there in Torcello. That’s Torcello there.”

…

That’s my town. There’s plenty more I could show you, but I think we probably ought to roll now. But take one good look at it. This is where you can see how it all happened.

But nobody ever looks at it from here.”

“It’s a beautiful view. Thank you, sir.”

“O.K.,” the Colonel said. “Let’s roll,”

This book takes place over three days. On day one, this is what the Colonel drinks (with page numbers):

So that’s five or six double martinis, three additional cocktails, and maybe two bottles of wine for the Colonel before bedtime.

This is not one of Hemingway’s more popular books. In Farewell To Arms, Sun Also Rises, and For Whom The Bell Tolls, the main character is young, cool, brave, competent, about as awesome a guy as you can think up. The Colonel, when we meet him, is calling his boatman a jerk. And he’s old (50) and busted up. He used to be a general but lost that rank. His mind is on pain, the past.

The Austrian attacks were ill-coordinated, but they were constant and exasperated and you first had the heavy bombardment which was supposed to put you out of business, and then, when it lifted, you checked your positions and counted the people. But you had no time to care for wounded, since you knew that the attack was coming immediately, and then you killed the men who came wading across the marshes, holding their rifles above the water and coming as slow as men wade, waist deep.

If they did not lift the shelling when it started, the Colonel, then a lieutenant, often thought, I do not know what we would be able to do. But they always lifted it and moved it back ahead of the attack. They went by the book.

If we had lost the old Piave and were on the Sile they would move it back to the second and third lines; although such lines were quite untenable, and they should have brought all their guns up very close and whammed it in all the time they attacked and until they breached us. But thank God, some high fool always controls it, the Colonel thought, and they did it piecemeal.

All that winter, with a bad sore throat, he had killed men who came, wearing the stick bombs hooked up on a harness under their shoulders with the heavy, calf hide packs and the bucket helmets. They were the enemy.

But he never hated them; nor could have any feeling about them. He commanded with an old sock around his throat, which had been dipped in turpentine, and they broke down the attacks with rifle fire and with the machine guns which still existed, or were usable, after the bombardment. He taught his people to shoot, really, which is a rare ability in continental troops, and to be able to look at the enemy when they came, and, because there was always a dead moment when the shooting was free, they became very good at it.

But you always had to count and count fast after the bombardment to know how many shooters you would have. He was hit three times that winter, but they were all gift wounds; small wounds in the flesh of the body without breaking bone, and he had become quite confident of his personal immortality since he knew he should have been killed in the heavy artillery bombardment that always preceded the attacks. Finally he did get hit properly and for good. No one of his other wounds had ever done to him what the first big one did. I suppose it is just the loss of the immortality, he thought. Well, in a way, that is quite a lot to lose.

The Colonel visits a place where he wounded fighting with the Italian army in the first World War – Fossalta. It’s the same place Hemingway himself was wounded while serving as a Red Cross volunteer. You could read The Colonel as being how Frederick Henry from Farewell to Arms turned out. This is almost a sequel.

The Colonel has a nineteen year old countess who loves him, but it’s accepted they can have no future together. This book is gloomy. We’re in a postwar Italy with bomb craters and ex-Fascists. In Hemingway’s other books lots of people die, but they weren’t Americans. The romance and European sexiness of Hemingway’s early books is gone. The Colonel recounts military ugliness, death, ordering men to die on orders:

The first day there, we lost the three battalion commanders.

One killed in the first twenty minutes and the other two hit later. This is only a statistic to a journalist. But good battalion commanders have never yet grown on trees; not even Christmas trees which was the basic tree of that woods. I do not know how many times we lost company commanders how many times over. But I could look it up.

They aren’t made, nor grown, as fast as a crop of potatoes is either. We got a certain amount of replacements but I can remember thinking that it would be simpler, and more effective, to shoot them in the area where they detrucked, than to have to try to bring them back from where they would be killed and bury them. It takes men to bring them back, and gasoline, and men to bury them. These men might just as well be fighting and get killed too.

Does it seem plausible that a beautiful nineteen year old Venetian countess would want to spend her time prodding a 51 year old US Army Colonel to tell her war stories? Bear in mind he’s an alcoholic grouch. It COULD be that’s more of a middle-aged guy’s fantasy? The countess doesn’t seem like a fully realized character to me. But so what? We’re still dealing with one of the best to ever do it here, there are amazing scenes and passages and moments that come to life.

Hemingway spoke about this book, as yet unpublished, in The New Yorker profile by Lillian Ross from 1950. That profile, you’ll recall, opens with Ross meeting Hemingway at Idlewild airport after a flight from Havana. When she arrives he’s got a fellow passenger in a headlock:

[Hemingway] crooked the arm around the briefcase into a tight hug and said that it contained the unfinished manuscript of his new book, “Across the River and into the Trees.” He crooked the arm around the wiry little man into a tight hug and said he had been his seat companion on the flight. The man’s name, as I got it in a mumbled introduction, was Myers, and he was returning from a business trip to Cuba. Myers made a slight attempt to dislodge himself from the embrace, but Hemingway held on to him affectionately.

“He read book all way up on plane,” Hemingway said. He spoke with a perceptible Midwestern accent, despite the Indian talk. “He like book, I think,” he added, giving Myers a little shake and beaming down at him.

“Whew!” said Myers.

“Book too much for him,” Hemingway said. “Book start slow, then increase in pace till it becomes impossible to stand. I bring emotion up to where you can’t stand it, then we level off, so we won’t have to provide oxygen tents for the readers. Book is like engine. We have to slack her off gradually.”

“Whew!” said Myers.

Hemingway released him. “Not trying for no-hit game in book,” he said. “Going to win maybe twelve to nothing or maybe twelve to eleven.”

Myers looked puzzled.

“She’s better book than ‘Farewell,’ ” Hemingway said. “I think this is best one, but you are always prejudiced, I guess. Especially if you want to be champion.” He shook Myers’ hand. “Much thanks for reading book,” he said.

Ross asks him his own opinion on the book:

“What do you think?” he said after a moment. “You don’t expect me to write ‘The Farewell to Arms Boys in Addis Ababa,’ do you? Or ‘The Farewell to Arms Boys Take a Gunboat’?” The book is about the command level in the Second World War. “I am not interested in the G.I. who wasn’t one,” he said, suddenly angry again. “Or the injustices done to me, with a capital ‘M.’ I am interested in the goddam sad science of war.” The new novel has a good deal of profanity in it. “That’s because in war they talk profane, although I always try to talk gently,” he said, sounding like a man who is trying to believe what he is saying. “I think I’ve got ‘Farewell’ beat in this one,” he went on. He touched his briefcase. “It hasn’t got the youth and the ignorance.” Then he asked wearily, “How do you like it now, gentlemen?”

The parts about the command level in the Second World War are most interesting. Here’s a small section:

“Tell me about when you were a General.”

“Oh, that,” he said and motioned to the Gran Maestro to bring champagne. It was Roederer Brut ’42 and he loved it.

“When you are a general you live in a trailer and your Chief of Staff lives in a trailer, and you have bourbon whisky when other people do not have it. Your G’s live in the C.P. I’d tell you what G’s are, but it would bore you. I’d tell you about GI, G2, G3, G4, Gs and on the other side there is always Kraut-6. But it would bore you. On the other hand, you have a map covered with plastic material, and on this you have three regiments composed of three battalions each. It is all marked in colored pencil.

“You have boundary lines so that when the battalions cross their boundaries they will not then fight each other.

Each battalion is composed of five companies. All should be good, but some are good, and some are not so good.

Also you have divisional artillery and a battalion of tanks and many spare parts. You live by co-ordinates.”

He paused while the Gran Maestro poured the Roederer Brut ’42.

“From Corps,” he translated, unlovingly, cuerpo d’Ar-mata, “they tell you what you must do, and then you decide how to do it. You dictate the orders or, most often, you give them by telephone. You ream out people you respect, to make them do what you know is fairly impossi-ble, but is ordered. Also, you have to think hard, stay awake late and get up early.”

“And you won’t write about this? Not even to please me?”

[The Colonel, once a general, goes on at some length about why he couldn’t possibly write any of this down.]

I can’t say the book is about the command level of WW2. The book is about Venice, being wounded, hurt, pain, wine, hotels, memory, impending death, regret, doomed love, being fifty-one. The Colonel keeps telling himself not to be morbid.

How Hemingway wrote it, from the Ross profile:

Hemingway poured himself another glass of champagne. He always wrote in longhand, he said, but he recently bought a tape recorder and was trying to get up the courage to use it. “I’d like to learn talk machine,” he said. “You just tell talk machine anything you want and get secretary to type it out.” He writes without facility, except for dialogue. “When the people are talking, I can hardly write it fast enough or keep up with it, but with an almost unbearable high manifold pleasure.

In his New York Times review of Across The River and Into the Trees, John O’Hara scolded The New Yorker for the profile’s emphasis on Hemingway’s drinking. O’Hara’s review boils down to “this may not be his best but it’s Hemingway.” I agree!

The title of the book comes from the dying words of Stonewall Jackson, recounted in the book. Here is the version reported by Stonewall Jackson’s medical officer, Hunter McGuire:

A few moments before he died he cried out in his delirium, “Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action ! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks ,” then stopped, leaving the sentence unfinished. Presently a smile of ineffable sweetness spread itself over his pale face, and he cried quietly and with an expression as if of relief, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees “; and then, without pain or the least struggle, his spirit passed from earth to the God who gave it.

The best parts of ATRAITT were a tribute to Venice:

I ought to live here. On retirement pay I could make it all right. No Gritti Palace. A room in a house like that and the tides and the boats going by. I could read in the mornings and walk around town before lunch and go every day to see the Tintorettos at the Accademia and to the Scuola San Rocco and eat in good cheap joints behind the market, on, maybe, the woman that ran the house would cook in the evenings.

I think it would be better to have lunch out and get some exercise walking. It’s a good town to walk in. I guess the best, probably. I never walked in it that it wasn’t fun. I could learn it really well, he thought, and then I’d have that.

It’s a strange, tricky town and to walk from any part to any other given part of it is better than working cross-word puzzles. It’s one of the few things to our credit that we never smacked it, and to their credit that they respected it.

I liked too the part where they eat a lobster:

Just then the lobster was served.

It was tender, with the peculiar slippery grace of that kicking muscle which is the tail, and the claws were excel-lent; neither too thin, nor too fat.

“A lobster fills with the moon,” the Colonel told the girl.

“When the moon is dark he is not worth eating.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“I think it may be because, with the full moon, he feeds all night. Or maybe it is that the full moon brings him feed.”

“They come from the Dalmatian coast do they not?”

“Yes,” the Colonel said. “That’s your rich coast in fish.”

Another good part is when the Colonel eats a thin slice of sausage and then some clams at the market.

They made this book into a film in 2022. It seems challenging to me, most of the story takes place in the Colonel’s head, not much happens, except some conversations, and like we said, gloomy. There are two duck hunts, a car ride, a long dinner, and a wandering in Venice, but that’s about it for action in the present time. Still, from the trailer it looks like Lieb Schreiber found something in the role:

Some sources on the last words of Stonewall Jackson:

Valipolcella/Valipolcello comes up a lot, wine, from this region:

Photo credit to NuKeglus on Wikipedia.

Husbands and wives

Posted: April 29, 2025 Filed under: family Leave a commentTwo illustrations from PD Eastman.

Can’t run baseball

Posted: April 21, 2025 Filed under: baseball Leave a comment

found in this book at a beach rental house.

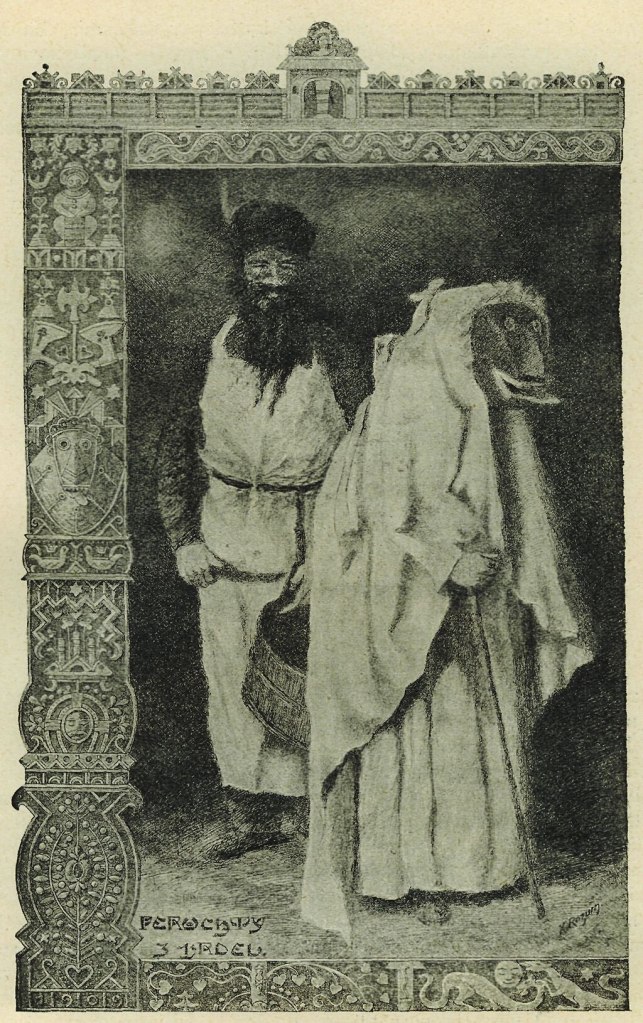

The House of Savoy

Posted: April 19, 2025 Filed under: France Leave a comment

I expect to be at the Annecy Animation Festival in Annecy, France this year, a great treat. If you’ll be there, hmu. As prep I’m reading about the history of that region, known as Savoy.

The land we call Savoie had a curious destiny: a land of empire in the Middle Ages, but divided from the outset between the call of the Rhône valley and that of the Po valley. Over the centuries, it was the cradle of a dynasty of French language and culture, but the fortunes of its history made it the mother of Italian unity, fighting at different times against the Dauphiné, against the Valais, against the Calvinist Geneva, against the Milan, and succeeding despite these incessant wars, It was for a long time a bone of contention between France and the Holy Roman Empire, then between France and Spain, and finally between France and Austria, and is now a link between the two friendly countries that occupy both sides of the Alps.

— André Chamson, Archives de l’ancien duché de Savoie (source.) From the same article:

Pre-Christian Alpine traditions date from this period (Austria, Switzerland, Savoy, Northern Italy, Slovenia), whose characters – Krampus, Berchta (Perchten), wild man – are part of an endangered, folklorized cultural heritage, on the verge of extinction due to the disappearance of traditional ways of life that have been preserved for longer in the Alps.

Bercha/Perchta

Humbert Whitehands was called that because his hands were as white as snow. Or because he was honest in his dealings, his hands were white. Or it’s a misunderstanding, it came from white walls, an easy confusion in sloppy Latin.

Charles Previté-Orton was a scholar of the early house of Savoy:

And he weighs in on what we can know from the years around 1000, and our sources:

He does seem to have put in the work. You can read his Early History of the House of Savoy online if you so choose.

It seems we can agree that Humbert I was granted the lands that became Savoy for his loyalty to Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II. There followed various Amadeuses and Humberts, until we get to Thomas, the Eagle of Savoy.

In 1195, Thomas ambushed the party of Count William I of Geneva, which was escorting the count’s daughter, Margaret of Geneva, to France for her intended wedding to King Philip II of France. Thomas carried off Margaret and married her himself.

So says Wikipedia. But Eugene L. Cox, who published a couple of books about the House of Savoy, isn’t so sure:

How much truth there is in this story we shall probably never know, except that Thomas did marry Guillaume’s daughter and in due course found himself faced with the very serious problem of providing suitably for his numerous offspring.

(Side note but if you’re at Wellesley College why not see if you can get the Eugene L. Cox Fellowship? $10,000 to go poke around some castles or something.)

Thomas’s children were married off and scattered into various religious and secular posts (the distinction not being very clear at the time) all over Europe. As a result, the family had wide influence. Cox:

the Savoyards did play a remarkable variety of roles on the international scene, sometimes as adventurers and sometimes as members of a kind of one-family “United Nations” working to assist in the pacification of international conflicts. Thanks partly to the labors of their father and, more literally, to the labors of their sister Béatrice, the countess of Provence whose four daughters all became European queens, the uncles from the Alps could by their presence alone convert a diplomatic conference into a family reunion, a fact which may have contributed to the settlement of some of the more emotional issues in which they were involved. As friends and ambassadors of kings and popes, as men with homes in many lands and connections that stretched from Scotland and Flanders to Sicily and Rome, the Savoyards furnish a very unusual illustration of medieval “universalism,” yet they were not men without a country. No matter how far afield their enterprises may have taken them, all of the eagles kept an eye on the Alpine homeland. Whenever they could, they contributed to the advancement of family interests in Savoy, and all but one returned to the Alps to end his days.

One of Thomas’s granddaughters, Eleanor of Provence, married the king of England. So many of her family came with her that an area of London became known as Savoy, thus the Savoy Hotel, which gave its name to a Harlem ballroom, and thus Stompin at the Savoy.

Eventually after Thomas there was the Green Count, Amadeus VI:

(source)

and then the Red Count, Amadeus VII, and then Amadeus VIII, the Peaceful, who was elevated to duke status.

He became a pope, or an anti-pope, depending on who you ask.

Léon Menabrea sums up the period with these words: “Little by little, the petty feudatories faded away; a star grew and blazed in the middle of the feudal firmament: the star of the House of Savoy“.

(source)

At this time the Annecy region was not part of Savoy, it was run by the Counts of Geneva. Robert of Geneva, one of the last counts, was elected the first of the French antipopes at Avignon. When he died, sonless, the title Count of Geneva went to Humbert VII, who then died, and the title went to Odo, who sold the region to Amadeus VIII for 45,000 gold florins. Why did Odo need florins so bad? I don’t know. French Wikipedia doesn’t elaborate. Odo wasn’t really expecting to become count of Geneva. How much was 45,000 gold florins? Let’s ask Perplexity AI:

The Florentine gold florin in the late 14th and early 15th centuries was a high-value coin used mainly for large transactions, not everyday purchases. Its value in modern terms is hard to pin down exactly, but estimates based on gold content, purchasing power, and historical wages offer some perspective:

- The gold content (about 3.5 grams) would be worth roughly $187 USD today based on current gold prices

- In terms of purchasing power, a florin could buy about 1/12 of a metric ton of wheat in the 1330s, which would equate to about $28–$30 USD in modern wheat prices1.

- In the 15th century, annual salaries for skilled professionals in Florence ranged from 14 to 100 florins, and a city residence might cost 200 florins, with elite palaces valued at 3,500 florins.

- The florin was worth between 65 and 140 soldi (a silver coin) during this period, and was used for major transactions, dowries, and international trade rather than daily expenses

In summary, a single gold florin represented a significant sum—roughly equivalent to several hundred modern US dollars, or more, depending on the comparison method

Not a bad deal. Call it 45 million dollars, and you get a bustling town with canals and a flowing river and big lake and a lot of nice land.

The trade didn’t include the city of Geneva, which was ruled by the bishops of Geneva.

In Peter Wilson’s history of the Holy Roman Empire, of which Savoy was a part, he mentions the following:

The rapid development of cartography from the fifteenth century made a profound impact by providing a ready image of territorially defined political power. Maps now showed political boundaries as well as natural features and towns. The members of the House of Savoy celebrated its elevation to ducal rank in 1416 with a huge cake in the shape of their territory.

Would’ve loved to have a slice of that.

Eventually, during the French Revolution, revolutionary troops took Annecy back, but the House of Savoy was going strong. You can follow the line of the House through battles, marriages, regents, half-brothers, etc to Victor Amadeus II, who, as a result of some complicated negotiations after the War of the Spanish Succession, ended up as King of Sicily. From this lofty job he was demoted to King of Sardinia.

In a set of trades and turnarounds, the actual land of Savoy ended up officially as part of France, while the House of Savoy, led by Victor Emmanuel II, became the royal family of the newly united Italy.

The story of what happened thereafter is entertainingly told in Robert Katz’s book The Fall of the House of Savoy, which is full of mistresses and cunning ministers and morganatic marriages.

One of these books where even the footnotes are good:

From this turbulence the House of Savoy ended up on top, and they survived World War One, but it was not to last.

Victor Emanuel III messed it up:

He remained silent on the domestic political abuses of Fascist Italy

sadly relevant to our time. Mussolini took over, and we all know how that ended. VEIII ended up in exile in Egypt. Umberto II, his son, spent years in exile in Portugal. He died in Geneva.

Umberto’s son Vittorio Emanuel led a seedy life, including shooting a 19 year old kid in a strange yacht incident, and going to jail on charges of organizing prostitutes for casino patrons. Here he is in happier times, watching the launch of Apollo 11:

source. His son was on Italian Dancing With the Stars, and granddaughter, Vittoria, is of course an influencer.

Thus, the house of Savoy.

I look forward to returning to this lovely part of the world!

You can beat a race, but you can’t beat the races

Posted: April 18, 2025 Filed under: business Leave a comment

Alex Morris has published a compilation of Buffett and Munger remarks at annual meetings. This allowed me to add to my file of times the two have talked about horse race betting and the lessons to be learned there.

Munger’s quote, in his Worldly Wisdom speech, is the bluntest of all:

How do you get to be one of those who is a winner—in a relative sense—instead of a loser? Here again, look at the pari-mutuel system. I had dinner last night by absolute accident with the president of Santa Anita. He says that there are two or three betters who have a credit arrangement with them, now that they have off-track betting, who are actually beating the house. They’re sending money out net after the full handle—a lot of it to Las Vegas, by the way—to people who are actually winning slightly, net, after paying the full handle. They’re that shrewd about something with as much unpredictability as horse racing. And the one thing that all those winning betters in the whole history of people who’ve beaten the pari-mutuel system have is quite simple. They bet very seldom. It’s not given to human beings to have such talent that they can just know everything about everything all the time. But it is given to human beings who work hard at it—who look and sift the world for a mispriced bet—that they can occasionally find one. And the wise ones bet heavily when the world offers them that opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they don’t. It’s just that simple. That is a very simple concept. And to me it’s obviously right—based on experience not only from the pari-mutuel system, but everywhere else.”

I noted professional horseplayer Inside The Pylons saying something related on his Bet With The Best podcast appearance:

Like you have no chance doing stuff like that long term. So you only bet the races where you think are good betting races.

But when you look at nine to nine or 10 races, Santa Anita, I mean, jeez, even if you’re sharp, I mean, if you bet more than three races a day, you’re a sicko I mean, there’s just so many bad races.

This theme recurs in the Morris compilation:

2003 MEETING (02:36:36) *

WB: “The beauty of the investment game, what really makes it great, is that you don’t have to be right on everything. You don’t have to be right on 20%, 10%, or even 5% of the companies in the world. You only have to get one good idea every year or two. I used to be very interested in horse handicapping, and the old story was you could beat a race but you can’t beat the races … If somebody gave me all five hundred stocks in the S&P and I had to make some prediction about how they would behave relative to the market over the next couple years, I don’t know how I would do. But maybe I could find one where I’m 90% sure I’m right. It’s an enormous advantage in stocks: You only have to be right on a very, very few things as long as you never make big mistakes.”

ACTIVE MANAGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS

1997 MEETING (01:21:40)

WB: “Money managers, in aggregate, have underperformed index funds. It’s the nature of the game. They simply cannot overperform, in aggregate. There are too many of them managing too big a portion of the pool. It’s for the same reason that the crowd could not come out here to Ak-Sar-Ben [racetrack] and make money, in aggregate, because there’s a bite taken out of every dollar that was invested in the pari-mutuel machines. People who invest their dollars elsewhere through money managers in aggregate cannot do as well as they could do by themselves in an index fund. They say you can’t get something for nothing. But the truth is money managers, in aggregate, have gotten something for nothing; they’ve gotten a lot for nothing. And the corollary is investors have paid something for nothing. That doesn’t mean people are evil.

FROM POOR INVESTMENTS

1995 MEETING (01:01:17)

WB: “A very important principle in investing is that you don’t have to make it back the way you lost it. In fact, it’s usually a mistake to try and make it back the way that you lost it.”

CM: “That’s the reason so many people are ruined by gambling; they get behind and then they feel they have to get it back the way they lost it. It’s a deep part of human nature. It’s very smart just to lick it by will; little phrases like that are very useful.”

WB: “One of the important things in stocks is that the stock does not know you own it. You have all these feelings about it; you remember what you paid and you remember who told you about it, all these little things. And it doesn’t give a damn, it just sits there. If a stock is at $50 when somebody’s paid $100, they feel terrible. Meanwhile, somebody else who paid $10 feels wonderful. It has no impact whatsoever. As Charlie says, gambling is the classic example. Someone goes out and gets into a mathematically disadvantageous game. They start losing it, and they think they’ve got to make it back, not only the way they lost it, but that night. It’s a great mistake.”

Some other words of interest: On ValueLine:

PATIENCE (WATCHING FOR HISTORIC FINANCIAL DATA)

1995 MEETING (03:54:41)

CM: “I think the one set of numbers that are the best quick guide to measuring one business against another are the Value Line numbers. That stuff on the log scale paper going back fifteen years, that is the best one-shot description of a lot of big businesses that exists. I can’t imagine anybody being in the investment business involving common stocks without that on their shelf.”

WB: “And, if you have in your head how all of that looks in different businesses and industries, then you’ve got a backdrop against which to measure. If you’d never watched a baseball game and never seen a statistic on it, you wouldn’t know whether a .3o0 hitter was a good hitter or not. You have to have some kind of a mosaic there that you’re thinking is implanted against, in effect. And the Value Line figures, if you ripple through that, you’ll have a pretty good idea of what’s happened over time in American business.”

CM: “I would like to have that material going all the way back; they cut it off at fifteen years back. I wish I had that in the office, but I don’t.”

WB: “I saved the old ones. We tend to go back. If I’m buying Coca-Cola, I’ll go back and read the Fortune articles from the 193os on it. I like a lot of historical background on things, just to get it in my head how the business has evolved over time, and what’s been permanent and what hasn’t been permanent, and all of that. I probably do that more for fun than for actual decision-making. We’re trying to buy businesses we want to own forever, and if you’re thinking that way you might as well look back a way and see what it’s been like to own them forever.”