Great coat of arms

Posted: April 3, 2025 Filed under: France Leave a comment

reading about Dauphiné, was wondering why this region of France was called that, and of course it’s because Guigues IV had a dolphin on his coat of arms.

Glimpses of Abraham Lincoln: awaiting election results with Charles Dana

Posted: April 3, 2025 Filed under: presidents, WOR Leave a comment

Charles Dana, former journalist and assistant secretary of war was with Abraham Lincoln as he awaited results of the election of 1864:

All the power and influence of the War Department, then something enormous from the vast expenditure and extensive relations of the war, was employed to secure the re-election of Mr. Lincoln. The political struggle was most intense, and the interest taken in it, both in the White House and in the War Department, was almost painful. After the arduous toil of the canvass, there was naturally a great suspense of feeling until the result of the voting should be ascertained. On November 8th, election day, I went over to the War Department about half past eight o’clock in the evening, and found the President and Mr. Stanton together in the Secretary’s office. General Eckert, who then had charge of the telegraph department of the War Office, was coming in constantly with telegrams containing election returns. Mr. Stanton would read them, and the President would look at them and comment upon them. Presently there came a lull in the returns, and Mr. Lincoln called me to a place by his side.

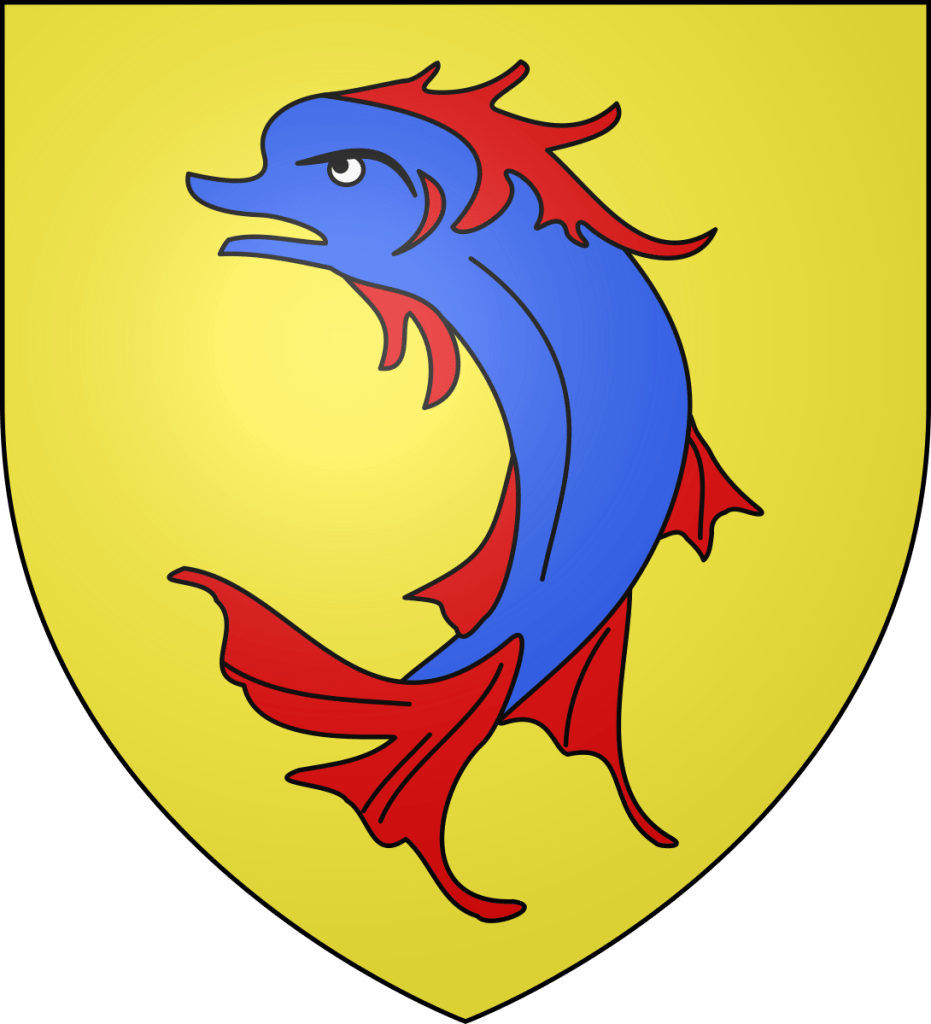

“Dana,” said he, “have you ever read any of the writings of Petroleum V. Nasby?”

“No, sir,” I said; “I have only looked at some of them, and they seemed to be quite funny.”

“Well,” said he, “let me read you a specimen”;

“let me read you a specimen”;

and, pulling out a thin yellow-covered pamphlet from his breast pocket, he began to read aloud. Mr. Stanton viewed these proceedings with great impatience, as I could see, but Mr. Lincoln paid no attention to that.

He would read a page or a story, pause to consider new election telegram, and then open the book again and go ahead with a new passage. Finally, Mr. Chase came in, and presently somebody else, and then the reading was interrupted.

Mr. Stanton went to the door and beckoned me into the next room. I shall never forget the fire of his indignation at what seemed to him to be mere nonsense.

The idea that when the safety of the republic was thus at issue, when the control of an empire was to be determined by a few figures brought in by the telegraph, the leader, the man most deeply concerned, not merely for himself but for his country, could turn aside to read such balderdash and to laugh at such frivolous jests was, to his mind, repugnant, even damnable. He could not understand, apparently, that it was by the relief which these jests afforded to the strain of mind under which Lincoln had so long been living, and to the natural gloom of a melancholy and desponding temperament-this was Mr. Lincoln’s prevailing characteristic-that the safety and sanity of his intelligence were maintained and preserved.

Petroleum Naseby was a character, a cowardly Copperhead who supported the Confederacy but didn’t want to do anything about it, invented by David Ross Locke.

In his day Locke was up there with Josh Billings and Mark Twain.

Val Kilmer

Posted: April 2, 2025 Filed under: actors 1 CommentCan’t forget him doing his one man show as Mark Twain at the Hollywood Cemetery. Afterwards he stayed on stage while he was taking his elaborate makeup off and asked the audience if they uncomfortable with him saying the n word so much.

The Doors, Tombstone, Heat, Spartan… he wasn’t just pretending, he was in it.

Kilmer briefly considered running for Governor of New Mexico in 2010, but decided against it.

What if?

Hely’s Grave

Posted: March 22, 2025 Filed under: Australia Leave a comment

Hely’s Grave is a heritage-listed grave at 559 Pacific Highway, Wyoming, Central Coast, New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by John Verge and built in 1836.

Hely’s Grave is the resting place of Frederick Augustus Hely, born in County Tyrone, Ireland, who ended up as superintendent of convicts in New South Wales in 1823. Was that a good job or a bad one? It must’ve been the equivalent of moving to the moon.

John Verge, the architect who designed this grave, also designed Hely’s house, Wyoming Cottage, which still stands and looks nice:

(Source)

Why did John Verge move to Australia? He was having success in London it seems. This may be a clue:

Verge’s marriage eventually failed and, in 1828, he migrated to Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, with his son George Philip, intending to take up a land grant.

His architectural legacy remains all over the Sydney area, I should like to go on a tour some day.

Frederick Hely’s son Hovendon Hely had an interesting career:

He took part in the 1846-47 expedition of Ludwig Leichhardt but was accused by Leichhardt of indolence, disloyalty and “disgusting” behaviour.

Interesting. More details are revealed by The Australian Dictionary of Biography:

Although described by Ludwig Leichhardt as a ‘likeable idler’, Hely joined his unsuccessful expedition of 1846-47. Leichhardt later accused him of disloyalty and dereliction of duty, after Hely and his relation, John Frederick Mann, had also disgusted Leichhardt ‘with their bawdy filthy conversations or with their constant harping on fine eating and drinking’.

Wonderful. “Likeable idler” is my dream job.

Ludwig Leichhardt, a German naturalist, had a curious nature.

His first expedition spanned a lot of northern Australia:

It was not without casualties. A vivid and blunt memorial to John Gilbert is on the wall of St. James Church in Sydney:

“Speared by the blacks.”

A second expedition doesn’t seem to have been much more successful:

Members of the party nearly mutinied after learning that Leichhardt had failed to bring along a medical kit. Faced with failure, Leichhardt seems to have suffered a nervous breakdown, and Aboriginal guide Harry Brown effectively took over as leader of the party, taking them successfully back to the Darling Downs.

Nevertheless Leichhardt kept at it. He tried another expedition and got malaria, survived, and went for one more. On this expedition, he went missing. Who was send to find him but Hovendon Hely:

In December 1851 Hely was appointed head of the official search for Leichhardt after the original appointee had drowned, but revealed little imaginative leadership. According to the Empire in 1864, the expedition ‘established nothing whatever’.

The fate of Leichhardt continues to inspire investigation, there are a number of intriguing clues like a brass plate and a letter recording an aboriginal oral history:

As for Hovendon Hely, he survived and had six sons and a daughter. Many Helys remain in Australia, among them both judges and murderers. So far as I know none of these Helys can be counted as relatives in any meaningful way, but any doorway into Australian history is welcome, and any explorations of that bizarre land are usually rewarded (as long as you don’t get speared).

If any of my Australian correspondents are available for a bit of field work, I’d like to learn why Hely’s Grave is reported by Google Maps as permanently closed. It’s a bit of a trek, an hour six minutes drive from the Park Hyatt Sydney. But on the plus side it’s across the street from a Hungry Jack’s

Carolina Whopper on me for anyone who reports.

Turned Inside Out: Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac by Frank Wilkeson

Posted: March 15, 2025 Filed under: WOR 1 CommentThis is one of the most vivid books I’ve ever read. It’s cinematic. It describes the journey of a teenage boy from upstate New York into hell. A harrowing journey in a series of scenes that get more and more intense. It’s like watching 1917 or something.

(Trigger warning: sad)

The war fever seized me in 1863. All the summer and fall I had fretted and burned to be off. That winter, and before I was sixteen years old, I ran away from my father’s high-lying Hudson River Valley farm. I went to Albany and enlisted in the Eleventh New York Battery, then at the front in Virginia, and was promptly sent out to a penitentiary building. There, to my utter astonishment, I found eight hundred or one thousand ruffians, closely guarded by heavy lines of sentinels, who paced to and fro, day and night, rifle in hand, to keep them from running away. When I entered the barracks these recruits gathered around me and asked, “How much bounty did you get?” “How many times have you jumped the bounty?” I answered that I had not bargained for any bounty, that I had never jumped a bounty, and that I had enlisted to go to the front and fight. I was instantly assailed with abuse. Irreclaimable blackguards, thieves, and ruffians gathered in a boisterous circle around me and called me foul names. I was robbed while in these barracks of all I possessed—a pipe, a piece of tobacco and a knife.

I remained in this nasty prison for a month. I became thoroughly acquainted with my com-rades. A recruit’s social standing in the barracks was determined by the acts of villany he had performed, supplemented by the number of times he had jumped the bounty. The social standing of a hard-faced, crafty pickpocket, who had jumped the bounty in say half a dozen cities, was assured.

The first people he sees killed are three men attempting to desert as they march down State Street in Albany. They take a steamboat to New York, where a guard kills another man trying to desert. Then they’re put on another steamboat:

Money was plentiful and whiskey entered through the steamer’s ports, and the guards drove a profitable business in selling canteens full of whiskey at $5 each. Promptly the hold was transformed into a floating hell. The air grew denser and denser with tobacco smoke.

Drunken men staggered to and fro. They yelled and sung and danced, and then they fought and fought again. Rings were formed, and within them men pounded each other fiercely. They rolled on the slimy floor and howled and swore and bit and gouged, and the delighted spectators cheered them to redouble their efforts. Out of these fights others sprang into life, and from these still others. The noise was horrible. The wharf became crowded with men eager to know what was going on in the vessel. A tug was sent for, and we were towed into the river, and there the anchors were dropped. Guards ran in on us and beat men with clubbed rifles, and were in turn attacked.

We drove them out of the hold. The hatch at the head of the stairs was closed and locked. The recruits were maddened with whiskey. Dozens of men ran a muck, striking every one they came to, and being struck and kicked and stamped on in return. The ventilation hatches were surrounded by stern-faced sentinels, who gazed into the gloom below and warned us not to try to get out by climbing through the hatches.

Men sprang high in the air and clutched the hatch railings, and had their hands smashed with musket butts. Sentinels paced to and fro along the vessel’s deck, and called loudly to all row-boats to keep off or they would be fired upon. They did not intend that any fresh supplies of whiskey should be brought to us. The prisoners in this floating hell were then told to “go it,” and they went it. We had been searched for arms before we entered the barracks at Albany. The more decent and quiet of us had no means of killing the drunken brutes who pressed on us. There was not a club or a knife or an iron bolt that we could lay our hands to. I fought, and got licked; fought again, and won; and for the third time faced my man, and got knocked stiff in two seconds. It was a scene to make a devil howl with delight.

They reach Alexandria, and then are put on a train to the Union winter camp at Brandy Station. Five more deserters are shot along the way. In the spring, Wilkeson is marched into Virginia. Along the road they pass the bones of unburied dead left from the battle of Chancellorsville.

As we sat silently smoking and listening to the story, an infantry soldier who had, unobserved by us, been prying into the shallow grave he sat on with his bayonet, suddenly rolled a skull on the ground before us, and said in a deep, low voice: “That is what you are all coming to, and some of you will start toward it tomorrow.” It was growing late, and this uncanny remark broke up the group, most of the men going to their regimental camps.

I found this book in a strange way. I was trying to sort out Grant’s Overland Campaign. Here’s an informative video of the strategic level. You can read Grant’s memoirs and many histories and accounts from officers. But what was it like? At Spotsylvania Courthouse, at the Mule Shoe Salient, there was a 22 hour hand to hand scrum, thousands of people killed in like a one square mile bit of earthworks. Did anyone survive to tell about that? In the course of investigating I did find these Australian guys recreating the battle with miniatures:

Their work is amazing.

I’d been playing around with testing various AIs on historical questions. I asked Claude:

What are some notable firsthand account of the fighting at mule shoe salient in the us civil war?

Claude came back with a numbered list of seven sources. Six were officers’ memoirs or official reports, and one was Frank Wilkeson’s “Recollections of a Private Soldier.”

Wilkeson wasn’t actually at the “mule shoe” I don’t think, but close enough. Strangely, on other occasions, Claude has completely made up sources that don’t exist. I go to check them and find they’re nothing, I tell Claude “hey can you give me more information about this, I can’t find it” and Claude says “I apologize, you’re right, I was mistaken.” Weird.

Anyway Frank Wilkeson is very real, his book was reprinted by University of Nebraska Press in 1997. The original title, Recollections of A Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac, is so boring that it possibly caused this book to be ignored. The new title, Turned Inside Out, refers to how the pockets of the dead would all be turned out by battlefield ghouls and robbers of the dead.

At one point Wilkeson actually sees Grant:

One of my comrades spoke to me across the gun, saying: “Grant and Meade are over there,” nodding his head to indicate the direction in which I was to look. I turned my head and saw Grant and Meade sitting on the ground under a large tree. Both of them were watching the fight which was going on in the pasture field. Occasionally they turned their glasses to the distant wood, above which small clouds of white smoke marked the bursting shells and the extent of the battle. Across the woods that lay behind the pasture, and behind the bare ridge that formed the horizon, and well within the Confederate lines, a dense column of dust arose, its head slowly moving to our left. I saw Meade call Grant’s attention to this dust column, which was raised either by a column of Confederate infantry or by a wagon train. We ceased firing, and sat on the ground around the guns watching our general, and the preparations that were being made for another charge.

Grant had a cigar in his mouth. His face was immovable and expressionless.

His eyes lacked lustre.

He sat quietly and watched the scene as though he was an uninterested spectator. Meade was nervous, and his hand constantly sought his face, which it stroked. Staff officers rode furiously up and down the hill carrying orders and information. The infantry below us in the ravine formed for another charge. Then they started on the run for the Confederate earthworks, cheering loudly the while. We sprang to our guns and began firing rapidly over their heads at the edge of the woods. It was a fine display of accurate artillery practice, but, as the Confederates lay behind thick earth-works, and were veterans not to be shaken by shelling the outside of a dirt bank behind which they lay secure, the fire resulted in emptying our limber chests, and in the remarkable discovery that three-inch percussion shells could not be relied upon to perform the work of a steam shovel. Our infantry advanced swiftly, but not with the vim they had displayed a week previous; and when they got within close rifle range of the works, they were struck by a storm of rifle-balls and canister that smashed the front line to flinders. They broke for cover, leaving the ground thickly strewed with dead and dying men. The second line of battle did not attempt to make an assault, but returned to the ravine. Grant’s face never changed its expression. He sat impassive and smoked steadily, and watched the short-lived battle and decided defeat without displaying emotion. Meade betrayed great anxiety. The fight over, the generals arose and walked back to their horses, mounted and rode briskly away, followed by their staff. No troops cheered them. None evinced the slightest enthusiasm.

The enlisted men looked curiously at Grant, and after he had disappeared they talked of him, and of the dead and wounded men who lay in the pasture field; and all of them said just what they thought, as was the wont of American volunteers. This was the only time that I saw either Grant or Meade under fire during the campaign, and then they were with. in range of rifled cannon only.

For a “you are there” quality of the War of the Rebellion – what Wilkeson calls “the suppression of the slaveholders’ revolt” – I’m not sure this book can be matched by anything I’m aware of except Ambrose Bierce and Sam Watkins. The power here is the scenes.

Before noon we came to the village of Bowling Green, where many pretty girls stood at cottage windows or doors, and even as close to the despised Yankees as the garden gates, and looked scornfully at us as we marched through the pretty town to kill their fathers and broth-ers. There was one very attractive girl, black-eyed and curly-haired, and clad in a scanty calico gown, who stood by a well in a house yard. She looked so neat, so fresh, so ladylike and pretty, that I ran through the open gate and asked her if I might fill my canteen with water from the well. And she, the haughty Virginia maiden, refused to notice me. She calmly looked through me and over me, and never by the slightest sign acknowledged my presence; but I filled my canteen, and drank her health. I liked her spirit.

Everybody who knows their Civil War history knows that a key moment was when Grant, after a disastrous first fight with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at the Wilderness, advanced instead of retreating like every previous Army of the Potomac commander. But Wilkeson’s there, man.

” Here we go,” said a Yankee private; “here we go, marching for the Rapidan, and the protection afforded by that river. Now, when we get to the Chancellorsville House, if we turn to the left, we are whipped at least so say Grant and Meade. And if we turn toward the river, the bounty-jumpers will break and run, and there will be a panic.”

“Suppose we turn to the right, what then?”

I asked.

“That will mean fighting, and fighting on the line the Confederates have selected and in-trenched. But it will indicate the purpose of Grant to fight,” he replied.

Then he told me that the news in his Sixth Corps brigade was that Meade had strongly advised Grant to turn back and recross the Rapidan, and that this advice was inspired by the loss of Shaler’s and Seymour’s brigades on the evening of the previous day. This was the first time I heard this rumor, but I heard it fifty times before I slept that night. The enlisted men, one and all, believed it, and I then believed the rumor to be authentic, and I believe it to-day. None of the enlisted men had any confidence in Meade as a tenacious, aggressive fighter. They had seen him allow the Confederates to escape destruction after Get-tysburg, and many of them openly ridiculed him and his alleged military ability.

Grant’s military standing with the enlisted men this day hung on the direction we turned at the Chancellorsville House. If to the left, he was to be rated with Meade and Hooker and Burnside and Pope-the generals who preceded him. At the Chancellorsville House we turned to the right. Instantly all of us heard a sigh of relief. Our spirits rose. We marched free. The men began to sing. The enlisted men understood the flanking movement. That night we were happy.

The site of the turn:

as it was:

James McPherson notes in the introduction, Shelby Foote and Bruce Catton took some of the best stuff from Wilkeson.

The most intense chapter of Wilkeson’s book is called “How Men Die In Battle.” You can read it here if you like. Here’s an excerpt (warning: intense, sad):

Near Spottsylvania I saw, as my battery was moving into action, a group of wounded men lying in the shade cast by some large oak trees. All of these men’s faces were gray. They silently looked at us as we marched past them. One wounded man, a blond giant of about forty years, was smoking a short briar-wood pipe. He had a firm grip on the pipe-stem. I asked him what he was doing. “Having my last smoke, young fellow,” he replied. His dauntless blue eyes met mine, and he bravely tried to smile. I saw that he was dying fast. Another of these wounded men was trying to read a letter. He was too weak to hold it, or maybe his sight was clouded. He thrust it unread into the breast pocket of his blouse, and lay back with a moan. This group of wounded men numbered fifteen or twenty. At the time, I thought that all of them were fatally wounded, and that there was no use in the surgeons wasting time on them, when men who could be saved were clamoring for their skillful attention. None of these soldiers cried aloud, none called on wife, or mother, or father. They lay on the ground, pale-faced, and with set jaws, waiting for their end. They moaned and groaned as they suffered, but none of them flunked. When my battery returned from the front, five or six hours afterward, almost all of these men were dead. Long before the campaign was over I concluded that dying soldiers seldom called on those who were dearest to them, seldom conjured their Northern on Southern homes, until they became delirious. Then, when their minds wandered, and fluttered at the approach of freedom, they babbled of their homes. Some were boys again, and were fishing in Northern trout streams. Some were generals leading their men to victory. Some were with their wives and children. Some wandered over their family’s homestead; but all, with rare exceptions, were delirious..

so I guess that’s what it was like.

In looking for info on the original Chancellor House I find this:

In the early 20th century, Susan Chancellor would often stop by for unannounced visits to the re-built house, much to the chagrin of a young girl who lived there with her family. “It was odd that she never knocked,” 89-year-old Hallie Rowley Sale told the Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star in 2003. “It was like she still thought of it as her home. We would hear a door open. And the next thing we knew, Mrs. Chancellor would be leading a group of people through the house.”

Movie idea

Posted: March 13, 2025 Filed under: film Leave a comment

Mikey Madison

is Dolley Madison.

Aaron Burr set her up with James Madison. A haunted photograph of her late in life.

More Conversations with Walker Percy

Posted: March 5, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

Vauthier: Mr. Percy, could we return to the question of time, and could you address the general problem of time in The Moviegoer?

Percy: Time? Well, at the end of the Mardi Gras season, the last scene and the last day of The Moviegoer is Ash Wednesday, so there’s a certain relevance here of the time of the action. The celebration of Mardi Gras is in New Orleans the biggest festival of the year with six weeks of parades and six weeks of parties. It ends with Ash Wednesday which is generally more or less ignored by most people who take part in Mardi Gras.

The role of the writer:

E.O.: Considering this very complicated contemporary scene, what is, to you, the role of a writer today?

W.P.: The role of a writer. Well, it seems to be, for me anyway, to affirm people, to affirm the reader. The general culture of the time is very scientific, one might call it “scientistic” on the one hand, and simply aesthetically oriented, on the other. This does not satisfy a certain reader. So, the reader is left in the state of confusion. The contemporary state of a young American man or woman is that he or she has more of the world’s affluence than any other people on this earth and yet he is more dissatisfied, more restless. He experiences some sense of loss which he cannot understand. For him, the traditional religion does not have the answer. So the role of my kind of writer is to speak to this person about this whole area of experience that he’s at or she’s at. This is what you feel, this is how you feel now. My original example in “The Message in the Bottle” is that you take a commuter, the man on the train. He has everything, he succeeded. He lives in Greenwich, Connecticut. He’s making a hundred thousand dollars a year, and he comes into New York every day. He’s moved into a better house, to a better country club, has a very nice wife and nice kids. He is riding on this train and he wonders: what am I doing? He can open a newspaper, and he can see a column which says something about the mid-life crisis. He can read some popular advice from a popular psychologist who would say why you have your mid-life crisis. But this doesn’t satisfy him. He picks up a book by an American writer, John Marquand, which is about a man like himself, a commuter on the train who has the same sense of loss. So, I say that there is a tremendous difference between a man on the train who is in a certain predicament and the same man on the same train with the same predicament who is reading a book about a man on the train. The role of a writer is very modest. It’s to identify the predicament. The letters I get are from people who say: I didn’t know anybody who talked like that, I know what you mean, you have described my predicament. I get letters from the businessmen (the men on the train), from young men, and from young women, and they’re excited because I’ve named the predicament.

That doesn’t sound like much, that’s a very modest contribution but it’s very important. You see, I agree with Kierkegaard. He said: “I’m not an apostle, it’s not for me to bring the good news. Even if I brought the good news, nobody would believe it.” But the role of a novelist, or an artist, for that matter, is to tell the truth, and to convey a kind of knowledge which cannot be conveyed by science, or psychology, or newspapers.

E.O.: Is this edifying?

W.P.: Edifying. You’ve picked up all the bad words. Well, “edify-ing” is a perfectly good word, but it has very bad connotations in English. Well, in the largest sense, it is edifying, because it’s helpful, it creates hope. At its best it’s affirming, it affirms the reader in the way he or she is. It offers an openness and some hope. And that’s about all a novelist can do.

How about this:

Interviewer: It is clear that once we are dealing with a “post-religious technological society,” transcendence is possible for the self by science or art but not by religion. Where does this leave the heroes of your novels with their metaphysical yearnings-Binx, Barrett, More, Lance?

Percy: I would have to question your premise, i.e., the death of relig-ion. The word itself, religion, is all but moribund, true, smelling of dust and wax-though of course in its denotative sense it is accurate enough.

I have referred to the age as “post-Christian” but it does not follow from this that there are not Christians or that they are wrong. Possibly the age is wrong. Catholics —who are the only Christians I can speak for-still believe that God entered history as a man, founded a church and will come again. This is not the best of times for the Catholic Church, but it has seen and survived worse. I see the religious “transcendence” you speak of as curiously paradoxical. Thus it is only by a movement, “transcendence,” toward God that these characters, Binx et al., become themselves, not abstracted like scientists but fully incarnate beings in the world. Kierkegaard put it more succinctly: the self only becomes itself when it becomes itself transparently before God.

From a profile:

He spent most of a decade writing two never-published novels, though now he swears he never felt discouraged “There was never a moment when I doubted what I wanted to do. It was always writing.” In the mid-1950’s, he began The Moviegoer. “I can remember sitting on that back porch of that little shotgun cottage in New Orleans with a little rank patio grown up behind it, after two failed novels. I didn’t feel bad. I felt all right.

“And it crossed my mind, what if I did something that American writers never do, which seems to be the custom in France: Namely, that when someone writes about ideas, they can translate the same ideas to fiction and plays, like Mauriac, Malraux, Sartre. So it just occurred to me, why not take these ideas I’d been trying to write about, in psychiatry and philosophy, and translate them into a fictional setting in New Orleans, where I was living. So I was just sitting out there, and I started writing.

How he starts:

“My novels start off, almost naturally, with somebody in a predicament and somebody trying to get out of it or embark on some sort of search, some sort of wanderings,” Percy says.

Permission to fail:

Visitor: Some people would rather not face their ordeals. What then?

Percy: I have a theory that what terrifies people most of all is failing to live up to something or other. This terror is the result of television shows, movies, and bad books where things always work out. Even in tragic movies, things are rounded off pretty well; people suffer nervous breakdowns in style and form. But, after all, whenever a movie is filmed, serious moviemakers collect 40 or 50 outtakes or failures, scenes that didn’t work, before they get one that works. So what the audience sees is the one that works. We should approach life that way.

We should give ourselves permission to fail.

My opinion? More Conversations with Walker Percy is even better than Conversations with Walker Percy!

Professor Longhair

Posted: March 4, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, music, New Orleans Leave a commentMardi Gras has me thinking about Professor Longhair. In his memoir Rhythm and Blues Jerry Wexler tells a story about Ahmet Ertegun finding the Professor:

I’d started noticing Atlantic’s early releases with Professor Long-hair’s “Hey Now Baby,” “Hey Little Girl,” and “Mardi Gras in New Orleans.” Fess—as the Professor was called—was a revelation for me, my first taste of the music being served up in Louisiana in the late forties.

There were traces of Jelly Roll Morton’s habanera-Cuban tango influence in his piano style, but the overall effect was startlingly original, a jambalaya Caribbean Creole rumba with a solid blues bottom.

In a foreshadowing of trips I myself would later take to New Orleans, Ahmet described the first of his many ethnomusicological expeditions. “Herb and I went down there to see our distributor and look for talent. Someone mentioned Professor Longhair, a musical shaman who played in a style all his own. We asked around and finally found ourselves taking a ferry boat to the other side of the Mississippi, to Algiers, where a white taxi driver would deliver us only as far as an open field. ‘You’re on your own,’ he said, pointing to the lights of a distant village. ‘I ain’t going into that n***ertown.’ Abandoned, we trudged across the field, lit only by the light of a crescent moon. The closer we came, the more distinct the sound of distant music—some big rocking band, the rhythm exciting us and pushing us on. Finally we came upon a nightclub—or, rather, a shack—which, like an animated cartoon, appeared to be expanding and deflating with the pulsation of the beat. The man at the door was skeptical. What did these two white men want? ‘We’re from Life magazine,’ I lied.

Inside, people scattered, thinking we were police. And instead of a full band, I saw only a single musician—Professor Longhair—playing these weird, wide harmonies, using the piano as both keyboard and bass drum, pounding a kick plate to keep time and singing in the open-throated style of the blues shouters of old. “ ‘My God,’ I said to Herb, ‘we’ve discovered a primitive genius.’ “Afterwards, I introduced myself. ‘You won’t believe this,’ I said to the Professor, ‘but I want to record you.’ “ ‘You won’t believe this,’ he answered, ‘but I just signed with Mercury.’

Ahmet recorded him anyway—“ I am many men with many names who play under many styles,” Fess used to say—and jewels from that first session remain in the Atlantic catalogue today, over four decades later.”

(source on that photo) Previous coverage of New Orleans.

The Fate of John Sedgwick

Posted: March 2, 2025 Filed under: photography, WOR Leave a commentOf General John Sedgwick, Grant wrote:

I had known him in Mexico when both of us were lieutenants, and when our service gave no indication that either of us would ever be equal to the command of a brigade. He stood very high in the army, however, as an officer and a man. He was brave and conscientious. His ambition was not great, and he seemed to dread responsibility. He was willing to do any amount of battling, but always wanted some one else to direct. He declined the command of the Army of the Potomac once, if not oftener.

and

he was never at fault when serious work was to be done

I was reading up on Timothy O’Sullivan, a somewhat mysterious character, and his haunting photographs:

On May 5, [Timothy] O’Sullivan and his camera were at the Wilderness where men fought in a virgin forest of oak and pine, choked with underbrush.

It was so thick the troops moved in single line, the powder smoke so heavy, that men stumbled blindly into enemy lines. Two days later OSullivan was with Grant, moving toward Spotsylvania, where on May 8, Grant and Lee faced each other again. One of the last pictures OSullivan made before the battle began was of his old friend General Sedgwick, who liked to describe himself as “practical as distinguished from the theoretical soldier,” standing on the steps of a house surrounded by his staff. A short time later Sedgwick would be killed, as he told a soldier dodging Rebel bullets not to worry, “they could not shoot an elephant at that distance.” The words had just fallen from his lips when he fell, killed by a sharpshooter.

That from James D. Horan, Timothy O’Sullivan: America’s Forgotten Photographer.

A firsthand account of the end of Sedgwick, from Martin McMahon, who was Sedgwick’s chief of staff:

After this brigade, by Sedgwick’s direction, had been withdrawn through a little opening to the left of the pieces of artillery, the general, who had watched the operation, resumed his seat on the hard-tack box and commenced talking about members of his staff in very complimentary terms.

He was an inveterate tease, and I at once suspected that he had some joke on the staff which he was leading up to. He was interrupted in his comments by observing that the troops, who during this time had been filing from the left into the rifle-pits, had come to a halt and were lying down, while the left of the line partly overlapped the position of the section of artillery. He stopped abruptly and said, ” That is wrong. Those troops must be moved farther to the right ; I don’t wish them to overlap that battery.” I started out to execute the order, and he rose at the same moment, and we sauntered out slowly to the gun on the right. About an hour before, I had remarked to the general, pointing to the two pieces in a half-jesting manner, which he well understood, ” General, do you see that section of artillery? Well, you are not to go near it today.” He answered good-naturedly, “McMahon, I would like to know who commands this corps, you or I? ” I said, playfully, “Sometimes I am in doubt myself”; but added, ” Seriously, General, I beg of you not to go to that angle; every officer who has shown himself there has been hit, both yesterday and to-day.” He answered quietly, ” Well, I don’t know that there is any reason for my going there.” ‘ When afterward we walked out to the position indicated, this conversation had entirely escaped the memory of both.

(you can see the inveterate half-jester in this portrait of him, taken probably in 1864, by Matthew Brady or one of his employees)

back to McMahon:

I gave the necessary order to move the troops to the right, and as they rose to execute the movement the enemy opened a sprinkling fire, partly from sharp-shooters. As the bullets whistled by, some of the men dodged. The general said laughingly, ” What! what! men, dodging this way for single bullets! What will you do when they open fire along the whole line? I am ashamed of you. They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” A few seconds after, a man who had been separated from his regiment passed directly in front of the general, and at the same moment a sharp-shooter’s bullet passed with a long shrill whistle very close, and the soldier, who was then just in front of the general, dodged to the ground. The general touched him gently with his foot, and said, ” Why, my man, I am ashamed of you, dodging that way,” and repeated the remark, ” They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” The man rose and saluted and said good-naturedly, ” General, I dodged a shell once, and if I hadn’t, it would have taken my head off. I believe in dodging.” The general laughed and replied, “All right, my man; go to your place.”

For a third time the same shrill whistle, closing with a dull, heavy stroke, interrupted our talk; when, as I was about to resume, the general’s face turned slowly to me, the blood spurting from his left cheek under the eye im a steady stream. He fell in my direction ; I was so close to him that my effort to support him failed, and I fell with him.

Colonel Charles H. Tompkins, chief of the artillery, standing a few feet away, heard my exclamation as the general fell, and, turning, shouted to his brigade-surgeon, Dr. Ohlenschlager. Major Charles A. Whittier, Major T. W. Hyde; and Lieutenant Colonel Kent, who had been grouped near by, surrounded the general as he lay. A smile remained upon his lips but he did not speak. The doctor poured water from a canteen over the general’s face. The blood still poured upward in a little fountain. The men in the long line of rifle-pits, retaining their places from force of discipline, were all kneeling with heads raised and faces turned toward the scene ; for the news had already passed along the line.

After the war, Timothy O’Sullivan accompanied several expeditions out west, and photographed stuff like this:

John Sedgwick was from Cornwall, Connecticut, which seems like a pleasant place. Mark Van Doren wrote a poem about it, here’s an excerpt:

The mind, eager for caresses,

Lies down at its own risk in Cornwall;

Whose hills,

Whose cunning streams,

Whose mazes where a thought,

Doubling upon itself,

Considers the way, lazily, well lost,

Indulge it to the nick of death–

Not quite, for where it curls it still can feel,

Like feathers,

Like affectionate mouse whiskers,

The flattery, the trap.

In Cornwall there’s House VI, an experiment in deconstructivist architecture (a failed experiment?)

The Sedgwicks are a big name in the Berkshires, although I don’t see that our John is connected to the Main Line with Kyra and Edie. There’s a monument to John Sedgwick in Cornwall, but it seems ununique, like a thousand other Civil War monuments:

On the other hand, there’s a monument of him at West Point that has a tradition attached:

Legend holds that if a cadet is deficient in academics, the cadet should go to the monument at midnight the night before the term–end examination, in full dress, under arms, and spin the rowels on the monument’s spurs. With the resulting good luck, the cadet will pass the test.

It seems like he might’ve enjoyed that.

sources, for the photo, for Waud’s drawing and more.

Snappy lines from Uncle Warren

Posted: February 24, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, business Leave a commentWarren Buffett at 94 still writing in a crisp, appealing style in his annual letter. Is he fibbing a bit when he brags about not doing due diligence on real estate purchases? And bragging on himself for how much tax he pays, when he surely uses every dodge he can? Maybe so. He’s a mythmaker.

A decent batting average in personnel decisions is all that can be hoped for. The cardinal sin is delaying the correction of mistakes or what Charlie Munger called “thumb-sucking.” Problems, he would tell me, cannot be wished away. They require action, however uncomfortable that may be.

The philosophy:

… we own a small percentage of a dozen or so very large and highly profitable businesses with household names such as Apple, American Express, Coca-Cola and Moody’s. Many of these companies earn very high returns on the net tangible equity required for their operations. At yearend, our partial-ownership holdings were valued at $272 billion. Understandably, really outstanding businesses are very seldom offered in their entirety, but small fractions of these gems can be purchases Monday through Friday on Wall Street, and very occasionally, they sell at bargain prices.

Inflation:

Paper money can see its value evaporate if fiscal folly prevails. In some countries, this reckless practice has become habitual, and, in our country’s short history, the U.S. has come close to the edge. Fixed-coupon bonds provide no protection against runaway currency.

Businesses, as well as individuals with desired talents, however, will usually find a way to cope with monetary instability as long as their goods or services are desired by the country’s citizenry. So, too, with personal skills. Lacking such assets as athletic excellence, a wonderful voice, medical or legal skills or, for that matter, any special talents, I have had to rely on equities throughout my life. In effect, I have depended on the success of American businesses and I will continue to do so.

One way or another, the sensible – better yet imaginative – deployment of savings by citizens is required to propel an ever-growing societal output of desired goods and services. This system is called capitalism. It has its faults and abuses – in certain respects more egregious now than ever – but it also can work wonders unmatched by other economic systems.

The insurance biz:

When writing P/C insurance, we receive payment upfront and much later learn what our product has cost us – sometimes a moment of truth that is delayed as much as 30 or more years.

(We are still making substantial payments on asbestos exposures that occurred 50 or more years ago.)

This mode of operations has the desirable effect of giving P/C insurers cash before

they incur most expenses but carries with it the risk that the company can be losing money – sometimes mountains of money – before the CEO and directors realize what is happening.

After some years of reading Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger materials these letters become kind of familiar, but it’s soothing, like hearing a folktale told once again with a few variations.

Juicy headline

Posted: February 23, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, the California Condition Leave a commentPicked up a copy of Los Angeles Daily Journal, Orange County Edition, and was intrigued by this story. The evidence seems lopsided:

Anaheim police officers arrested Ferguson at his home in August 2023 after receiving a report of a shooting. Ferguson told officers at the scene and his court clerk via text that he shot his wife, Sheryl, after the couple returned home from dinner, according to affidavits filed in 2023 by Orange County District Attorney Todd Spitzer’s office.

Seeking more information I found this:

The couple’s adult son called 911 to report the shooting. A court filing from prosecutors states Ferguson texted his court clerk and bailiff minutes after the killing: “I just lost it. I just shot my wife. I won’t be in tomorrow. I will be in custody. I’m so sorry.”

…

Earlier that day, Ferguson had been drinking when he argued with his wife about finances during dinner at a local restaurant and later while watching “Breaking Bad” at home with their adult son, said prosecutor Seton Hunt. At one point in the evening, Ferguson made a gun hand gesture toward her, and she later chided him to point a real one at her, Hunt said.

Ferguson proceeded to do so and pulled the trigger, Hunt said.

Just a strange little story in California. Reminded of Hemingway in A Moveable Feast while he’s on a road trip with Scott Fitzgerald:

While waiting for the waiter to bring the various things I sat and read a paper and finished one of the bottles of Macon that had been uncorked at the last stop. There are always some splendid crimes in the newspapers that you follow from day to day, when you live in France. These crimes read like continued stories and it is necessary to have read the opening chapters, since there are no summaries provided as there are in American serial stories and, anyway, no serial is as good in an American periodical unless you have read the all-important first chapter. When you are traveling through France the papers are disappointing because you miss the continuity of the different crimes, affaires, or scandales, and you miss much of the pleasure to be derived from reading about them in a cafe. Tonight I would have much preferred to be in a café where I might read the morning editions of the Paris papers and watch the people and drink something a little more authoritative than the Macon in preparation for dinner. But I was riding herd on Scott so I enjoyed myself where I was.

In the same paper:

I found this phrase vivid:

“We had a phrase in dependency: ‘Clear is kind,” she said. “If you’re clear about what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and what orders mean, people are more likely to comply.”

Power by Jeffrey Pfeffer (2010)

Posted: February 22, 2025 Filed under: advice, America Since 1945, business Leave a comment

Pulled this one from my shelf because I remembered there was a funny claim about how flattery 100% of the time no exceptions always works. Indeed:

Most people underestimate the effectiveness of flattery and therefore underutilize it. If someone flatters you, you essentially have two ways of reacting. You can think that the person was insincere and trying to butter you up. But believing that causes you to feel negatively about the person whom you perceive as insincere and not even particularly subtle about it. More importantly, thinking that the compliment is just a strategic way of building influence with you also leads to negative self-feelings— what must others think of you to try such a transparent and false method of influence? Alternatively, you can think that the compliments are sincere and that the flatterer is a wonderful judge of people— a perspective that leaves you feeling good about the person for his or her interpersonal perception skill and great about yourself, as the recipient of such a positive judgment delivered by such a credible source. There is simply no question that the desire to believe that flattery is at once sincere and accurate will, in most instances, leave us susceptible to being flattered and, as a consequence, under the influence of the flatterer.

So, don’t underestimate—or underutilize-the strategy of flattery.

University of California-Berkeley professor Jennifer Chatman, in an unpublished study, sought to see if there was some point beyond which flattery became ineffective. She believed that the effectiveness of flattery might have an inverted U-shaped relationship, with flat tery being increasingly effective up to some point but beyond that becoming ineffective as the flatterer became seen as insincere and a “suck up.” As she told me, there might be a point at which flattery became ineffective, but she couldn’t find it in her data.

Amazing. A powerful move:

I have observed similar ploys used to gain power in business meetings. In most companies, the strategy and market dynamics are taken for granted. If someone challenges these assumptions-such as how the company is competing, how it is measuring success, what the strategy is, who the real competitors are now and in the future— this can be a very potent power play. The questions and challenges focus attention on the person bringing the seemingly commonsense…

How to get powerful? There’s a simple plan:

The fundamental principles for building the sort of reputation that will get you a high-power position are straightforward: make a good impression early, carefully delineate the elements of the image you want to create, use the media to help build your visibility and burnish your image, have others sing your praises so you can surmount the self-promotion dilemma, and strategically put out enough negative but not fatally damaging information about yourself that the people who hire and support you fully understand any weaknesses and make the choice anyway. The key to your success is in executing each of these steps well.

A tale of California politics:

In government, Jesse Unruh, a former Democratic political boss and treasurer of Califor-nia, called money the mother’s milk of politics. Former two-term San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, whose 16 years as speaker and virtual ruler of the California Assembly prior to becoming mayor marked him as an extremely effective politician, began his campaign for the legislative leadership post by raising a lot of money. And since he was from a “safe” district, he gave that money to his legislative colleagues to help them win their political contests. Brown understood an important principle: having resources is an important source of power only if you use those resources strategically to help others whose support you need, in the process gaining their favor. In contrast to Brown, the Assembly speaker at the time, Leo McCarthy, irritated his Democratic colleagues to the point of revolt by holding a $500,000 fundraiser in Los Angeles featuring Ted Kennedy and then using 100 percent of the money for his nascent efforts to run for statewide office.’ He was soon out of his job, replaced by Willie Brown.

(Similar schemes are a theme in Caro’s LBJ book, he got lots of money from powerful Texas guys to whom he steered government contracts for projects like dams, then he distributed that money around Congress to his desperate colleagues).

If you want power don’t give up power:

You need to be in a job that fits and doesn’t come with undue political risks, but you also need to do the right things in that job. Most important, you need to claim power and not do things that give yours away. It’s amazing to me that people, in ways little and big, voluntarily give up their power, preemptively surrendering in the competition for status and influence. The process often begins with how you feel about yourself. If you feel powerful, you will act and project power and others will respond accordingly. If you feel power-less, your behavior will be similarly self-confirming.

Restaurants and Railroads: Chili’s Triple Dip Boom

Posted: February 20, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, beverages, business, food 1 Comment

Once I’m cast off from show business perhaps I’ll start a newsletter called Restaurants and Railroads. This will analyze those two types of businesses, specifically publicly traded companies. Hedge funds as well as passionate hobbyists will subscribe. They’ll invite me to their conferences, to which I’ll travel in style, by rail when possible. I’ll sample the various restaurants as I go, Tijuana Flats for example, and Pizza Inn which I’ve never tried. In a world of niche media I wonder if I could make that work.

You might not think restaurants and railroads are a natural combination. Fred Harvey might disagree, but I’ll concede they’re very different businesses. The railroads have no new competition, no one is building a new railroad. Only a handful of companies control all the track. Two railroads serve the port of LA: one is BSNF, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, and one is Union Pacific. A duopoly.

The restaurants on the other hand are in frantic, constant competition. They must capture taste and vibe. Tastes change, vibes shift. Plus your customer could always just make a sandwich. How restaurants stay profitable? How do they maintain quality, especially at scale?

These two differing business categories are the two I’m excited to read about when I get an issue of ValueLine. Consumer Staples, Metals & Mining, etc, these lose our interest. But take a look at a personality like Kent Taylor’s or a real railroader like Hunter Harrison (or Casey Jones) and the mind comes to life, it’s hard to get bored.

In the publicly traded restaurant space, a big story this year has been Chili’s:

Chili’s may have just pulled off one of the greatest comebacks in restaurant history.

Same-store sales at the bar and grill chain surged more than 31% from October to December, marking its best quarter since the period just after COVID and accelerating a streak of double-digit same-store sales increases that began last April.

The growth once again was driven by a mix of social media buzz, value-based advertising and a renewed focus on restaurant operations and atmosphere that seemed to snowball as the year progressed.

Just to put this into context, these numbers are comparable to when Popeye’s went off with their spicy chicken sandwich. CEO Kevin Hochman points to TikTok:

About halfway through last year, its Triple Dipper appetizer platter, a staple on the chain’s menu for years, went viral on TikTok, where young customers showed off their “cheese pulls” with the Triple Dipper’s fried mozzarella sticks. …

“What’s happening is that young people are coming in after they’ve seen us on TikTok, and they’re like, ‘Wow, this experience is really good,’ and it becomes a part of the rotation,” Hochman told analysts during an earnings call Wednesday. “I think that’s why you’ve seen the longevity in the results and the acceleration, not just kind of a boom-splat that you typically would see without the operational investments that we’ve made in the business.”

Kevin Hochman seems like a brand guy: while at P&G he worked on Old Spice. $EAT stock has indeed thrived:

On an episode of A Deeper Dive, a quick service restaurant business podcast, the host and guest discussed Chili’s phenomenal success, and possible reasons for it. The fast food competitive price with the sit down experience came up, as did the mix and match. But in the end they agreed people just kinda like it.

It does seem like Chili’s is doing something right:

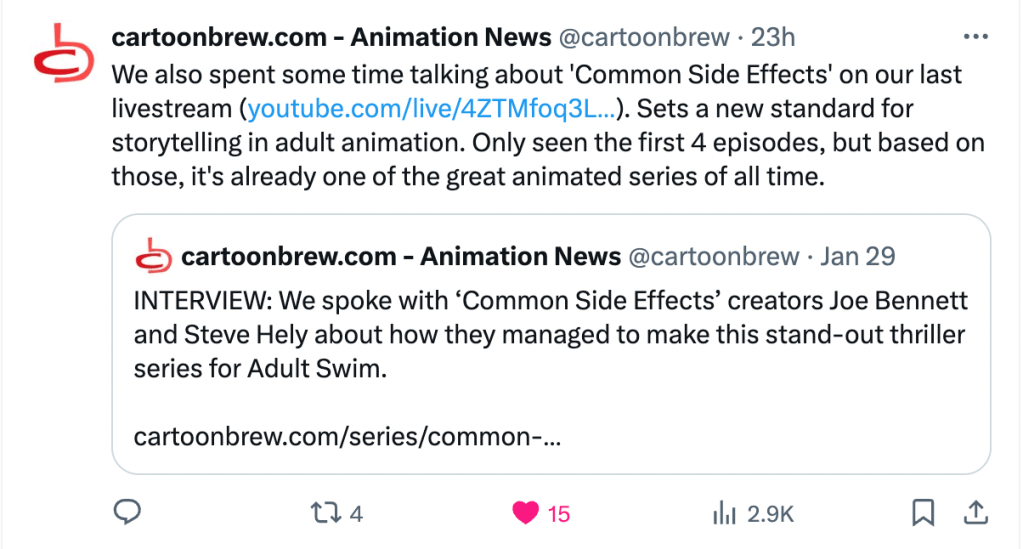

New Common Side Effects ep drops tonight

Posted: February 16, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentSome stills:

Art on this show is so good

Team is so talented

A Copano study from last week by Nove Escobedo:

11:30pm on Adult Swim, streaming next day on Max. Spread the word!

Mystery of the 27,574 muskets collected at Gettysburg

Posted: February 15, 2025 Filed under: War of the Rebellion, WOR Leave a comment

From Randall Collins, Violence: A Micro Sociological Theory. He’s speaking on firing rates among soldiers in wartime:

But the firing ratio in parade-ground formations was far from maximal. In American Civil War battles, 90 percent of muzzle-loading muskets collected after the battle of Gettysburg were found loaded, and half of those were multiply loaded, with two or more rounds on top of one another in the barre!

(Grossman 1995: 21-22); this implies that at least half the troops, at the moment they were hit or threw away their arms, had been repeatedly going through the motions of loading, but without actually firing, time after time. As we see later, casualties produced by these mass-formation troops were not high, and that could be attributed partly to non-firing, partly to inaccurate firing.

Collins thesis is that face to face violence is very hard for humans, it causes great stress and tension. In this section he’s arguing that even soldiers in battle have great difficulty shooting at each other, and often fire high or otherwise avoid shooting at each other. This detail got my attention, I wanted to know more. Collins source is David Grossman, On Killing. Grossman says:

Author of the Civil War Collector’s Encyopedia F. A. Lord tells us that after the Battle of Gettysburg, 27,574 muskets were recovered from the battlefield. Of these, nearly 90 percent (twenty-four thousand) were loaded. Twelve thousand of these loaded muskets were found to be loaded more than once, and six thousand of the multiply loaded weapons had from three to ten rounds loaded in the barrel. One weapon had been loaded twenty-three times. Why, then, were there so many loaded weapons available on the battlefield, and why did at least twelve thousand soldiers misload their weapons in combat?

A loaded weapon was a precious commodity on the black-powder battlefield. During the stand-up, face-to-face, short-range battles of this era a weapon should have been loaded for only a fraction of the time in battle. More than 95 percent of the time was spent in loading the weapon, and less than 5 percent in firing it. If most soldiers were desperately attempting to kill as quickly and efficiently as they could, then 95 percent should have been shot with an empty weapon in their hand, and any loaded, cocked, and primed weapon dropped on the battlefield would have been snatched up from wounded or dead comrades and fired.

There were many who were shot while charging the enemy or were casualties of artillery outside of musket range, and these individuals would never have had an opportunity to fire their weapons, but they hardly represent 95 percent of all casualties. If there is a desperate need in all soldiers to fire their weapon in combat, then many of these men should have died with an empty weapon. And as the ebb and flow of battle passed over these weapons, many of them should have been picked up and fired at the enemy.

The obvious conclusion is that most soldiers were not trying to kill the enemy. Most of them appear to have not even wanted to fire in the enemy’s general direction. As Marshall observed, most soldiers seem to have an inner resistance to firing their weapon in combat. The point here is that the resistance appears to have existed..

The amazing thing about these soldiers who failed to fire is the they did so in direct opposition to the mind-numbingly repetitive drills of that era. How, then, did these Civil War soldiers consistently “fail their drillmasters when it came to the all-important loading drill?

Some may argue that these multiple loads were simply mistakes, and that these weapons were discarded because they were misloaded. But if in the fog of war, despite all the endless hours of training, you do accidentally double-load a musket, you shoot it anyway, and the first load simply pushes out the second load. In the rare event that the weapon is actually jammed or nonfunctional in some manner, you simply drop it and pick up another. But that is not what happened here, and the question we have to ask ourselves is, Why was firing the only step that was skipped? How could at least twelve thousand men from both sides and all units make the exact same mistake?

Did twelve thousand soldiers at Gettysburg, dazed and confused by the shock of battle, accidentally double-load their weapons, and then were all twelve thousand of them killed before they could fire these weapons? Or did all twelve thousand of them discard these weapons for some reason and then pick up others? In some cases their powder may have been wet (even through their oiled-paper coating), but that many? And why did six thousand more go on to load their weapons yet again, and still not fire? Some may have been mistakes, and some may have been caused by bad powder, but I believe that the only possible explanation for the vast majority of these incidents is the same factor that prevented 80 to 85 percent of World War II soldiers from firing at the enemy. The fact that these Civil War soldiers overcame their powerful conditioning to fire through drill clearly demonstrates the impact of powerful instinctive forces and supreme acts of moral will…

Griffith’s figures make perfect sense if during these wars, as in World War Il, only a small percentage of the musketeers in a regimental firing line were actually attempting to shoot at the enemy while the rest stood bravely in line firing above the enemies’ heads or did not fire at all.

Well now hang on.

Let’s start with, how do we know this? What’s our source? This statistic on the 27,574 muskets, where do we get that?

I don’t have a copy of The Civil War Collector’s Encyclopedia handy. But luckily, with all questions related to the American Civil War, you can find the answer on some forum or another, which led me to this article, citing a source from 1867:

It seems strange to me that you would ship loaded weapons from Gettsyburg to Washington. Wouldn’t that be dangerous? Or maybe they weren’t likely to go off without the percussion cap? I’m not expert on Civil War firearms and don’t intend to become one. Still, the mystery puzzled me. Wouldn’t most of these weapons be kinda fucked up from being knocked around and exploded and so on? What does it tell us about the firing or non-firing of soldiers during the battle? Maybe these weapons were loaded and their unlucky holders were knocked out of action before they could be used?

A source the forum posters frequently point to is Paddy Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War. Paddy Griffith was an English scholar: here is a lovely obituary of him, he died in 2010.

Large, convivial yet dedicated to the serious analysis of military history, Paddy Griffith was a fearless challenger of the accepted versions of events and an iconoclastic war-gamer.

The absolute extremes of research in military history matters are often reached by war gamers and amateurs of various sorts. If you try and get to the ultimate authority on Civil War gunboats, for instance, you’ll end up being directed to The Western Rivers Steamboat Cyclopoedium, which is really a set of plans for model builders.

Anyway Griffith’s book arrived, and it’s excellent.

Vividly written, profound, a tremendous aid to understanding the Civil War in every way, from how troops carried their stuff and trained and spent their time to the macro history of the war, full of detail and extracts from memoirs and history. From the preface:

The past, of course, is a foreign country, and every historian is to some extent a tourist looking in from the outside upon the people and events he describes. In my own case, I have an added perspective as a British citizen who has literally been a tourist to many of the battlefields on which the Civil War was fought…

Both the tourist and the historian have a duty to be clear about their motives, especially in a case like the Civil War which remains important in modern-day life…

The experience of attaining military age also seems to have left me with another legacy, for like many another before me I became fascinated to discover just what a battle is, or was, like – preferably without actually venturing into one in person. I suspect that this somewhat unhealthy obsession is really quite common among military historians, and it can even be seen as a precondition of their calling. Each generation has had its own group of military writers who have wished to see the elephant of warfare without getting too close to it, and then relay their findings faithfully and truly to their readers.

It so happens that one of the most successful of all attempts to see the elephant in a war book was made in a novel about the American Civil War – about the battle of Chancellorsville, to be precise. This was of course Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, first published in 1894 when the author was only twenty-three years of age. It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this work to the general development of war writing, since its influence has been enormous and its perceptions remain as fresh and vigorous today as when they were originally penned. The amateur elephant watcher is especially captivated by what Crane had to say, and is led on inevitably into a closer examination of the Civil War battles. There is a sense in which Crane has consecrated these particular combats for every student of battles. I, for one, freely acknowledge my debt to him in much of what follows…

For the student of Napoleonic tactics, accustomed to a thin and insubstantial diet of secondary sources and unreliable data, the Civil War comes as a severe shock to the metabolism. It provides an unexpectedly rich feast of detailed personal memoirs, a cornucopia of fine regimental histories, and a solid dessert of circumstantial after-action reports. The student may gorge himself on these delicacies until he can move no more, yet still find that he has barely scraped the surface of what is on offer. In this respect, at least, the Civil War can indeed be seen as the first modern war. The spread of education and the desire to record personal experiences on paper is here exponentially greater than anything seen in Napoleonic times, even among Wellington’s endlessly scribbling light infantry. This wealth of first-hand evidence, furthermore, has been lovingly preserved and sifted by succeeding generations in a manner that puts modern Napoleonic studies to shame. Civil War history remains a living subject today, whereas Napoleonic analysis was all but killed off in 1914.° Indeed, this qualitative difference between the way the two eras have been studied may perhaps have helped to conceal their essential underlying unity.

Whereas the Napoleonic campaigns have been subconsciously relegated to a distant past, those of the Civil War are still being discovered in all their freshness from primary sources – lending them an air of modernity that may be subtly misleading.

There’s a touch of Bill James to Paddy Griffith’s passion. His book illuminated the War of the Rebellion for me in many ways. Among other things, it’s often pretty funny. You find this in the Civil War literature. Sam Watkins is very funny, even as he’s describing stumbling near-barefoot from disaster to disaster. Here’s Griffith describing a battle situation:

By 1864 it seems that there were numerous cases of combat refusal when an attack on fortifications was proposed. Even if this did not lead to a formal mutiny it could often lead to an ‘attack’ which went to ground almost before it had crossed its start line. The abortive ‘battle’ of Mine Run was an example of this on the grandest possible scale, since the entire Army of the Potomac came into position to storm Lee’s works but then thought better of it and went home.

The action of 35th Massachusetts at Spotsylvania provides a good example of how the 1864 fighting must often have been conducted. The regiment advanced behind another unit until it came under fire, when a bounty-jumper shouted ‘Retreat!’ and the whole regiment routed in panic. They rallied calmly when they had regained their own earthworks, insulted their new general (whom they did not recognise), then advanced again to a position in open ground one hundred yards from the enemy entrenchments. “Then the whole line lay down, without firing a shot, and in this position calmly sustained the fire of the enemy two or three hours, with little loss to us as the shells and bullets of the Confederates passed over our heads. The order was simply to ‘feel the enemy’, and as it was plain they were ready to receive us, no final assault was ordered.”

And that’s from their own regimental history! (Company I of the 35th Massachusetts was made up of men from Dedham, Needham and Weston, incidentally).

This decline to really get after it battlewise would seem well in line with Collins’ thesis, that people will do almost anything to avoid face to face violence. Griffith mentions many cases where individuals preferred to joke around or share supplies when they were supposed to be killing each other. On the other hand, Griffith describes plenty of situations where the two sides really did just stand there and blast away at each other at close range until one side couldn’t take it. As Shelby Foote says (discussing naval battles), it’s almost unbelievable, but they did it!

The amazing things about naval engagements are the accounts of men firing eight-inch guns at each other from a range of eight-feet. I’m afraid that is beyond my understanding. But they did it all the time in naval battles. It was a very strange business.

Let’s return to the matter of the collected muskets from Gettysburg. Here’s what Griffith says

An often quoted set of statistics from Gettysburg has it that the Union forces salvaged 27,574 ‘muskets’ after the battle, of which 24,000 were loaded, including 12,000 loaded twice, 6,000 loaded between three and ten times, one with twenty-three charges and one with twenty-two balls and sixty-six buckshot. Some had six balls and only one charge of powder; others had six unopened cartridges. Others again had the ball behind the powder instead of the other way round.

It is open to doubt whether twenty-three full cartridges could in fact be physically squeezed into the barrel of a Civil War rifle, and still more dubious that the proportion of misloaded weapons in the sample (some 45 per cent) actually reflects the proportion in the whole of the two armies during combat. It is most likely that many of the guns salvaged by the Union forces after Gettysburg were discarded by their users precisely because they had become unusable, hence the figure of 12,000 should be seen as a proportion of the total muskets in the battle rather than of the total salvaged. That suggests that perhaps 9 per cent of all muskets were misloaded – a less dramatic figure, but nevertheless still very significant. If we add the unknown total of misloaded muskets which were either salvaged by the Confederates or retained by their original owners, we are forced back to the conclusion that a very high proportion of infantry weapons must indeed have become inoperative in combat due to faulty handling.

Thus, it seems like these extra-loaded muskets weren’t unshot because their holders didn’t want to, contra Collins and Grossman. It was because they were busted.

A Civil War battle like any battle was totally chaotic and loud; Griffith’s book is largely about the problems of dealing with chaos, confusion, missed communication, strange terrain, and how people handled or failed to handle these challenges effectively. How to approach the truth of what happened in such a situation is an endless puzzle. Trying to get as close as possible to the source in this case has proved interesting. Griffith got as close as we’re likely to get, here are his sources:

My guy was tracking down unpublished doctoral theses to make his war games as accurate as possible. Despite the somewhat grim subject matter (guys blasting away at each other) learning about Griffith has uplifted my feelings about human nature and the power of curiousity. For those without any particular passion for the subject Griffith’s cover illustration probably tells you everything you need to know about a Civil War battle, although ironically no source is listed beyond “Cover Design by Maggie Mellett”.

Hopper’s America, discussing that painting, Dawn at Gettysburg:

Hopper himself relayed a story, told to him by a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, about Albert Einstein’s viewing of ‘Dawn Before Gettysburg’ in a show at MoMA.

‘Einstein in going through the galleries had stopped a long time before this picture of mine,’ Hopper said, ‘and I suppose it was his hatred of war that prompted him to do this as these men were evidently all ready for the slaughter.’

It’s easy to see why this little painting has made such an impact over the years. The colors are breathtaking, in particular the blood red of the dawn sky.

The individual soldiers are just that: individuals. As Warner points out, one has a blister on his foot from marching. Another has just vomited and is leaning on his friend, deathly ill. A standing soldier is getting orders ready, representing duty to his country.

I’ll have to discuss these matters with my uncle Dan next time I see him, he lives quite close to the battlefield. As we’ve discussed before Civil War battlefields can be very peaceful and pleasant to visit. They tend to be preserved farm and pastureland. It’s nice to be in a field.

(Previous coverage of Gettysburg, and the War of the Rebellion in general).

Finding water on the plains

Posted: February 8, 2025 Filed under: Texas 1 Comment

“You can blindfold me, me, take me anywhere in the Westen country; Goodnight once said, ‘then uncover my eyes so that I can look at the vegetation, and I can tell about where I am.

The mesquite, for instance, has different forms for varying ali. tudes, latitudes, and areas of aridity. It does not grow lat north of old Tascosa in the Texas Panhandle.

‘When I was scouting on the Plains, I was always mighty glad to see a mesquite bush. In a dry climate — the climate natural to the mesquite — its seed seem to spring up only from the droppings of an animal. The only animal on the Plains that ate mesquite beans was the mustang. After the mesquite seed was soaked for a while in the bowels of a horse and was dropped, it germinated quickly. Now mustangs rarely grazed out from water more than three miles, that is, when they had the country to themselves. Therefore, when I saw a mesquite bush I used to know that water was within three miles. All I had to do after seeing the bush was to locate the direction of the water.

“The scout had to be familiar with the birds of the region,” continued the plainsman, ‘to know those that watered each day, like the dove, and those that lived long without watering, like the Mexican quail. On the Plains, of an evening, he could take the course of the doves as they went off into the breaks to water. But the easiest of all birds to judge from was that known on the Plains as the dirt-dauber or swallow. He flew low, and if his mouth was empty he was going to water. He went straight too. If his mouth had mud in it, he was coming straight from water. The scout also had to be able to watch the animals, and from them learn where water was. Mustangs watered daily, at least in the summertime, while antelopes sometimes went for months without water at all. If mustangs were strung out and walking steadily along, they were going to water. If they were scattered, frequently stopping to take a bite of grass, they were coming from water.

‘West of the Cross Timbers water became very scarce, and near the Plains extremely bad. Most of it was undrinkable, and the water we could drink had a bad effect on us. At times we suffered exceedingly from thirst, which sufiering is the worst torture of all. At night we tossed in a semi-conscious slumber in which we unfortunately dreamed of every spring we ever knew — and such draughts as we would take from them – which invariably awakened us, leaving us, if possible, in even more distress. In my early childhood we had a fine spring near the house under some large oaks. A hollow tree had been provided for a gum, as was common in those days, and was nicely covered with green moss. Many times I have dreamed of seeing that spring and drinking out of it — it would seem so very real!

‘Suffering from thirst had a strange and peculiar effect. Every ounce of moisture seemed to be sapped out of the flesh, leaving men and animals haggard and thin, so that one could not recognize them if they had been deprived long.

‘Interior recruits had little knowledge of how to take care of themselves in such emergencies. In case of dire thirst, placing a small pebble in the mouth will help, a bullet is better, a piece of copper, if obtainable, is still better, and prickly pear is the best of all. Of course there were no pears on the Plains, but in the prairie country there were many. If, after cutting off the stickers and peeling, you place a piece of the pear in your mouth, it will keep your mouth moist indefinitely. If your drinking water happens to be muddy, peel and place a thin slice of pear in it. All sediment will adhere to it and it will sink to the bottom, leaving the water clear and wholesome.”

Simple, you just see if a swallow’s mouth is muddy. Charles Goodnight was hardcore. Following doves through the breaks is not easy.

Spoonful

Posted: February 7, 2025 Filed under: America Since 1945, music Leave a commentHave been listening to Spoonful as recorded by Howlin Wolf lately.

The lyrics relate men’s sometimes violent search to satisfy their cravings, with “a spoonful” used mostly as a metaphor for pleasures, which have been interpreted as sex, love, and drugs

Chester Arthur Burnett was born in White Station Mississippi, near West Point, in the “Black Prairie” (later remarketed as the “Golden Triangle“). JD Walsh digs up a photo, source undescribed, of our guy working on a horse’s hoof while he was in the 9th Cavalry.

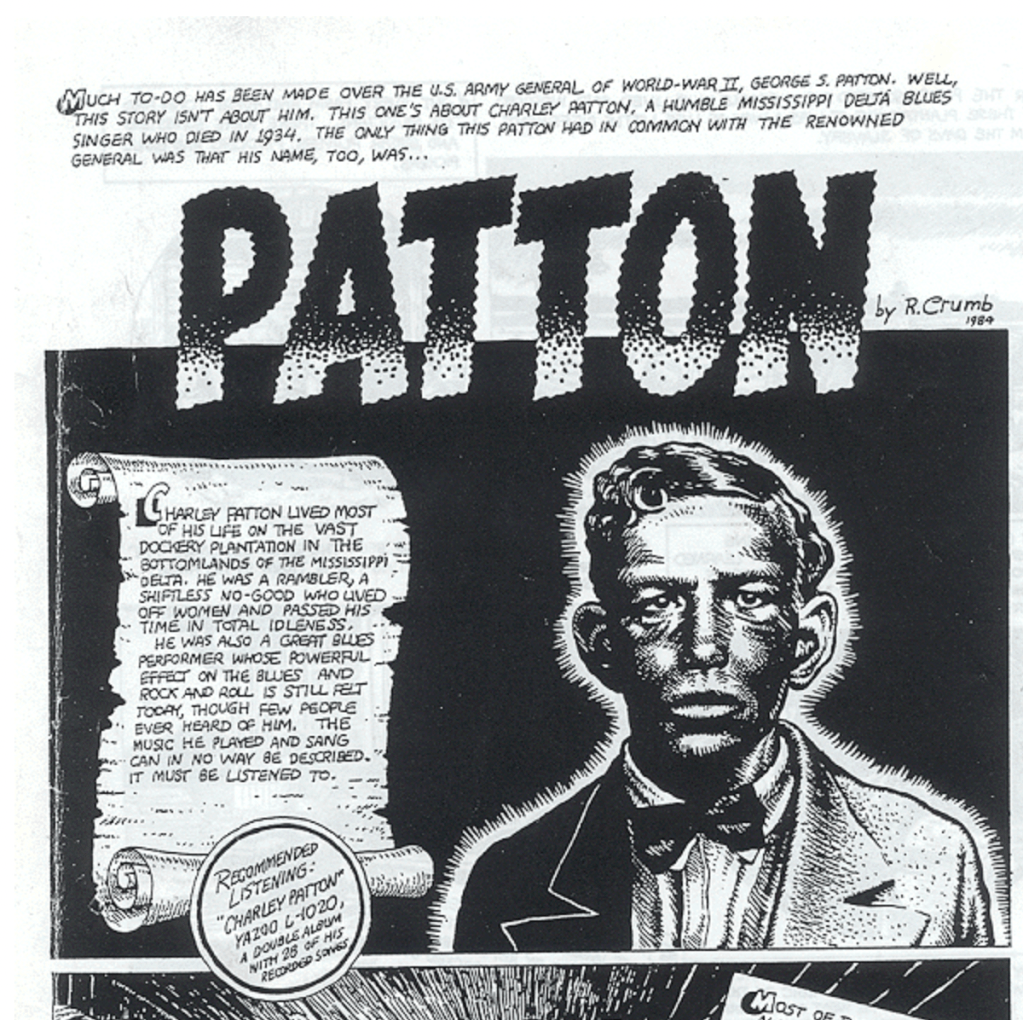

Howlin Wolf was an apprentice/student to Charlie Patton. I first heard about Charlie Patton from R. Crumb’s comic, which was reprinted in an anthology of underground comics they had at the Needham Public Library.

The Library also had a cassette of some of these blues guys. Living walking distance to the library, a life-changer.

Blues research is a famous graveyard for the curious – we’ve gone about as far as we dare on this topic, see previous coverage. Listening to Charlie Patton especially with the warble of the old recordings sounds spooky, and there’s a desire to see this as emerging from some mysterious beyond, but the turth might be more interesting, these people were modern. Elijah Wald shed some light on Delta blues in his book Escaping the Delta: