Rich people paying for elections

Posted: October 13, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

This is “good” in a way I guess, but this isn’t supposed to be how this works:

CASH SPLASH — “Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan donate $100 million more to election administrators, despite conservative pushback,” by WaPo’s Michael Scherer: “Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, announced Tuesday an additional $100 million in donations to local governments to pay for polling place rentals, poll workers, personal protective equipment and other election administration costs over the coming weeks.

“The donation, which follows a previous gift of $300 million for state and local governments to help fund U.S. elections, comes in the face of a lawsuits from a conservative legal group seeking to block the use of private funds for the state and local administration of elections, an expense that has historically been paid for by governments. But Zuckerberg has been unmoved by legal threats, arguing in a Facebook post expected to go live Tuesday that his decision to fund election administration does not have a partisan political motive.” WaPo

Via Politico. Shouldn’t states and local areas tax appropriately to have the money needed to run elections, rather than rely on the largesse of billionaires? Troubled. Are we veering to more of a straight-up oligarchy/democracy hybrid?

Absalom, Absalom

Posted: October 9, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

Finally finished this one. How about this part, about New Orleans:

I can imagine him, with his puritan heritage – that heritage peculiarly Anglo-Saxon – of fierce proud mysticism and that ability to be ashamed of ignorance and inexperience, in that city foreign and paradoxical, with its atmosphere at once fatal and languorous, at once feminine and steel-hard – this grim humorless yokel out of a granite heritage where even the houses, let alone clothing and conduct, are built in the image of a jealous and sadistic Jehovah, put suddenly down in a place whose denizens had created their All-Powerful and His supporting hierarchy-chorus of beautiful saints and handsome angels in the image of their houses and personal ornaments and voluptuous lives.

The Civil War approaches:

And who knows? there was the War now; who knows but what the fatality and the fatality’s victim’s did not both think, hope, that the War would settle the matter, leave free one of the two irreconciliables, since it would not be the first time that youth has taken catastrophe as a direct act of Providence for the sole purpose of solving a personal problem which youth itself could not solve.

The cover of my 1987 edition:

MW tells me he doesn’t approve, because Sutpen’s beard is supposed to be red (I myself didn’t clock that in the text, which probably requires a couple readings).

The barebones plot of this book: ambitious youth sets out to make his fortune, rises through courage and violence, through will hacks out an empire for himself, is dest on its own could make for a pretty sexy TV miniseries or something: ambition, pride, violence, incest. But the way it’s told, with the story embedded in retellings of retellings, and sentences that fold upon themselves for six or seven pages isn’t too breezy. From Wikipedia:

The 1983 Guinness Book of World Records says the “Longest Sentence in Literature” is a sentence from Absalom, Absalom! containing 1,288 words.[8] The sentence can be found in Chapter 6; it begins with the words “Just exactly like father”, and ends with “the eye could not see from any point”. The passage is entirely italicized and incomplete.

Strange analogy but some of the verbal pyrotechnics of this book sort of reminded me of the FX show Dave.

when Dave busts out one of his long raps. Indisputably impressive feat of language and cognition but… to what end? A stunning demonstration of what a person might be capable of, itself maybe a worthy achievement, but do I need to pretend that it made me feel anything other than kind of numbed? At what point are we just showing off, or just pounding the reader’s head in?

I don’t think Faulkner would necessarily appreciate that comparison.

Shelby Foote, in one of his interviews, tells us that Faulkner had hopes this would be a bestseller:

I wonder if more people last year read Absalom, Absalom or Gone With The Wind.

The story of David’s rebellious son Absalom is recounted in the Bible and the subject of a popular (?) Sacred Harp song.

Cocoanut milk

Posted: October 8, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

I’ve been adding a dash of cocoanut milk to my cold brew in the mornings. Recommend! Just when you think, “there can’t be a new milk to play with!”

Time for a walk?

Posted: October 8, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

from:

Important to remember: Bruce Chatwin made stuff up all the time.

The Kun Lung mountains are no joke:

Imagine

Posted: October 3, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

Imagine being the anonymous stranger who inspired Stevie Nicks’ whole style. From an LA Times/Yahoo profile by Amy Kaufman.

Cheyenne Chiefs Receiving Their Young Men

Posted: September 28, 2020 Filed under: art history, Indians Leave a comment

Artist unknown, 1881, from the Bethel Moore Custer Ledger, one of many amazing works over at Plains Indian Ledger Art.

Bethel Moore Custer was, apparently, not related to the “other” Custer.

Crown Journeys series

Posted: September 27, 2020 Filed under: travel, writing Leave a comment

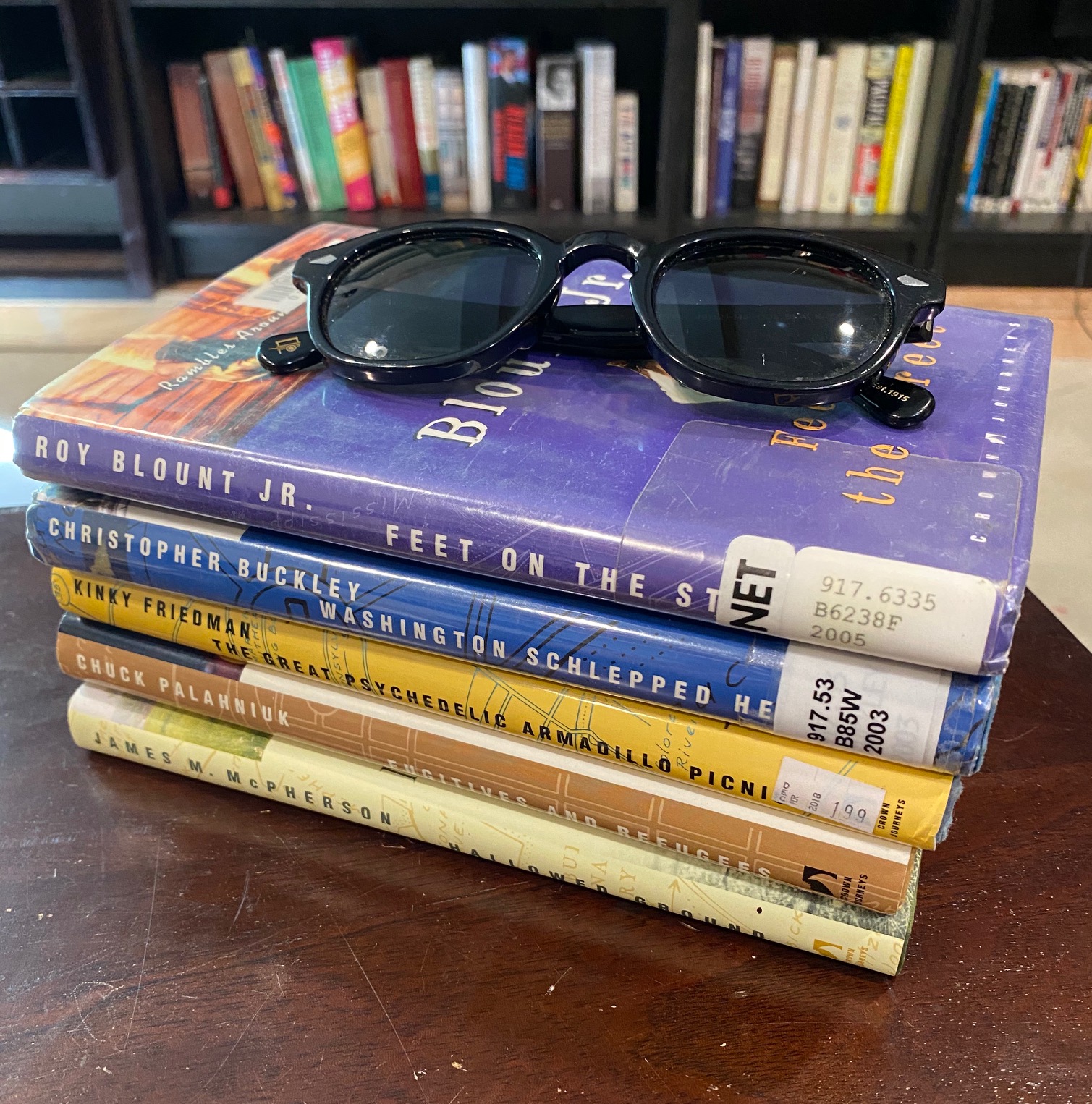

sunglasses for scale

I was listening to Chuck Palahniuk on Bret Easton Ellis podcast (is this the second post in a row where I mention this podcast? It’s not for everybody but I’m into it!)

You know, if somebody had given David Foster Wallace or Sylvia Plath fourteen issues of Spider-Man to do, they’d both still be alive

says Palahniuk early in the episode. An outrageous claim. But hey, I guess outrageous claims were what I was signing up for. Would ❤️ to read a Sylvia Plath Spider-man series.

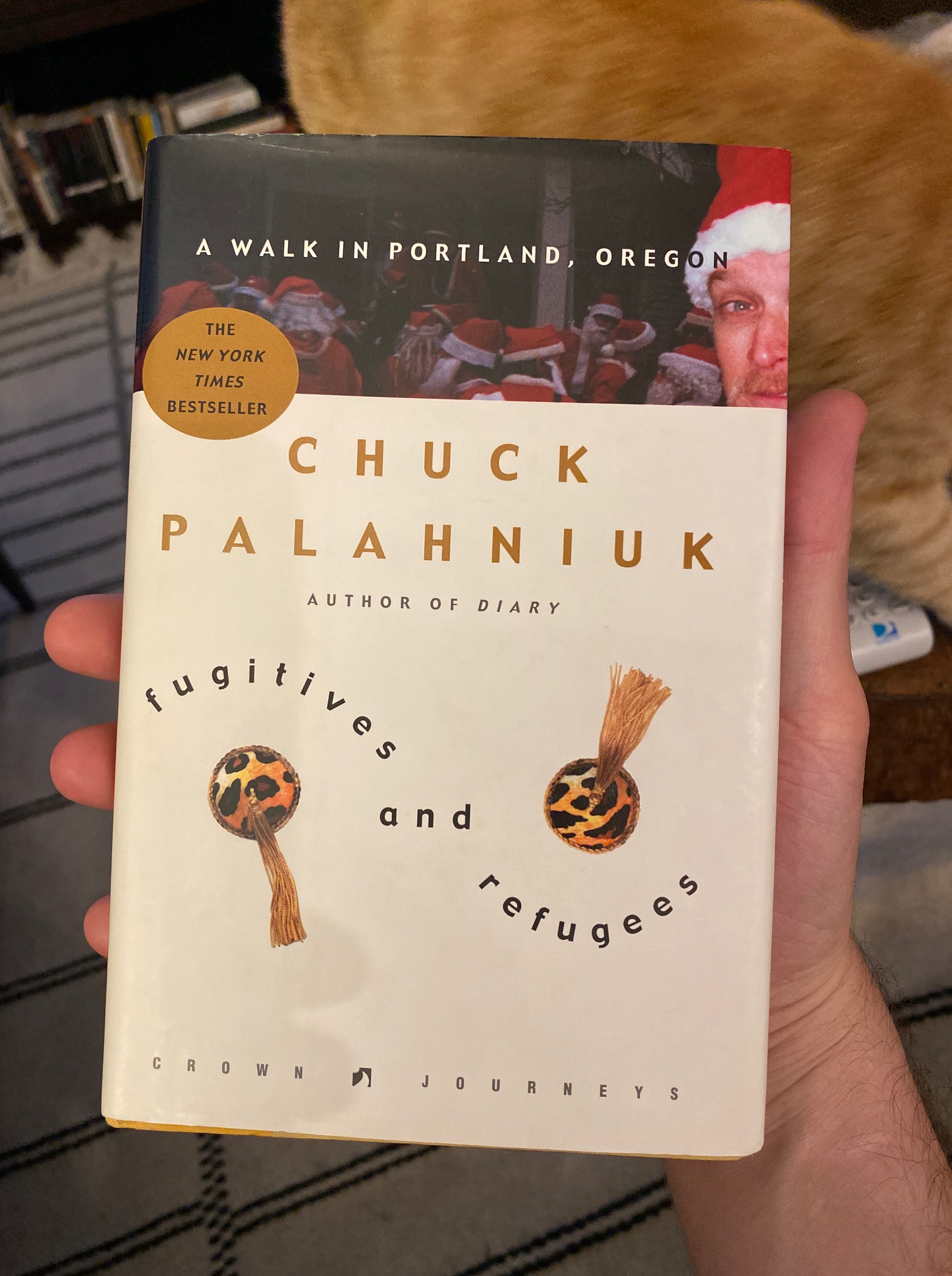

Palahniuk isn’t a writer I’ve read much of, gross out, extremist fiction not being my kinda milkshake. But when Palahniuk mentioned that he’d written a travel book about Portland, that got my attention. Travel books I’m into. So I got Palahniuk’s travel book, fugitives and refugees: A Walk In Portland, Oregon, which it turns out is part of a series Crown put out, Crown Journeys, where writers do a walking tour – sometimes pretty literally, sometimes in quotes – of a place they know well.

Turns out I’d read one of these already, Frank Conroy’s Time and Tide: A Walk Through Nantucket. I’d read that a few years back during a weeklong stay on Nantucket, but I remember nothing from it. The book about Nantucket I like is Charles Olson’s Call Me Ishmael, where I learned there was a neighborhood on Nantucket called New Guinea, full of people of color of various kinds. Nantucket’s worth a post of her own someday.

Stuck homebound, I got a bunch of these Crown Journeys books. An appealing quality of them is their size, just right to stuff in a bag:

Let’s start with Palahniuk’s. It’s a travel guide plus a memoir, the voice is strong and he shows, even rubs your face in, the weirdness of that town, the grubbiness and beauty all swished up together.

Katherine’s theory is that everyone looking to make a new life migrates west, across America to the Pacific Ocean. Once there, the cheapest city where they can life is Portland. This gives us the most cracked of the crackpots. The misfits among misfits.

The memory and madness:

Days, I’m working as a messenger, delivering advertising proofs form the Oregonian newspaper. Nights, I wash dishes at Jonah’s seafood restaurant. My roommates come home, and we throw food at each other. One night, cherry pie, big sticky red handfuls of it. We’re eighteen years old. Legal adults. So we’re stoned and drinking champagne every night, microwaving our escargot. Living it up.

Palahniuk is clearly more into the sex trade, underground (literal and figurative) side of the town, but he covers the gardens too, along with the Self Cleaning House and Stark’s Vacuum Cleaner Museum and the standout landmarks, along with a semi-autobiography full of vivid, intense incidents, like a beating and a moment with the mother of a dying hospital patient.

Although this book was published in 2003, reading it gives insight into why Portland is the arena of choice for “antifa” and far-night political violence LARPers and a fracture zone of America 2020.

The Seattle Public Library’s loss is my gain.

Next up, Roy Blount Jr.’s Feet On The Street: Rambles Around New Orleans.

This one’s the best organized, divided into seven rambles: Orientation, Wetness, Oysters, Color, Food, Desire, Friends. It’s full of jokes and stories and anecdote. Of all the Crown Journeys I read, this one’s unsurprisingly the most focused on food. How can you not want a “roast beef sandwich with debris” from Mothers, or a pan-fried trout topped with “muddy water” sauce: chicken broth, garlic, anchovies, and gutted jalapeños and sprinkled with parmesan cheese.”

Blout’s book is full of autobiography too, quoting from letters he wrote as a young man, describing nights and dinners, what New Orleans meant to him as a young man and what he found on frequent returns.

I’ll bet I have been up in N. O. at every hour in every season,

he says, a cool claim.

Towards the end of the book, Blount Jr. turns kind of reflective, ruminating with some regret on an incident of insensitivity, somewhere between misunderstanding and even cruelty, towards a homosexual friend that ended badly. There’s an air of regret to it, and maybe that’s part of New Orleans, too. Feet On The Street might work best of all of these, as a book. I’ve read a lot of guides to New Orleans and this one’s a fine addition to the canon.

Blount’s a figure who doesn’t seem to quite exist as much any more, the sort of literary semi-comedian raconteur, where books are just one expression of a humorous personality. Christopher Buckley’s another guy like that.

Washington Schlepped Here is, in my opinion, the worst titled of these books. It’s a pun, first of all, but second, George Washington simply never “schlepped.” Didn’t happen. He was not a schlepper. Buckley spends a paragraph or two dealing with the title, although he seems quite pleased with it. “Pleased with himself” might be the most accurate criticism you could make of Christopher Buckley, but it’s hard not to be a little won over by his privileged charm.

Buckley’s Washington is strictly the Washington of our nation’s capital. You won’t find anything in here about the majority black population of that city. How can you write a book about Washington that doesn’t mention Ben’s Chili Bowl? E. J. Applewhite’s Washington Itself, which Buckley quotes from copiously, is a richer one volume guide to the city. But there’s a Yale-grade wit to Buckley, I won’t deny it.

I’ll let you prowl about. There’s a lot to see: the Old Senate Chamber, Statuary Hall, the Crypt, the Old Supreme Court Chamber, the Hall of Columns, along with enough murals, portraits, busts and bas reliefs to keep you going “Huh” for hours.”

Buckley takes the walking tour conceit the most seriously of any of the writers. There’s a bummer element hanging over this book, as Buckley keeps pointing out how post-9/11 security procedures and jersey barriers have made wandering the capital city less free that in it used to be. There’s a bit of filler to this one, too, as if Buckley’s sort of just taking the Wikipedia page to certain buildings and adding a few quips. A few pages are devoted to musing on specific works in specific Mall art museums. Several of the jokes rely casual shared stereotypes about politics, like that Republicans like martinis, that now feel like they’re from another universe (the book was published in 2003).

The best parts of this one come from Jeanne Fogle’s book Proximity to Power and Tony Pitch’s walking tour, both centered on Lafayette Square, which bring to life people who lived here. Places are only so interesting. It’s people that get your attention.

James M. McPherson’s Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg is just terrific. A concise, powerful tour of the battlefield, rich in detail and incident, you’re clearly in the hands of a master storyteller who knows his stuff deeply. One of McPherson’s gifts is to take us not just to the battle as it happened, but to the battlefield as it’s remembered and preserved. McPherson talks about the way the woodlands on the battlefield would’ve been more thinned out in 1863, who could see what from where, how small features of geography shaped those three days. On the artillery barrage that preceded Pickett’s Charge:

Confederate gunners failed to realize the inaccuracy of their fire because the smoke from all these guns hung in the calm, humid air and obscured their view. Several explanations for this Confederate overshooting have been offered. One theory is that as the gun barrels heated up, the powder exploded with greater force. Another is that the recoil scarred the ground, lowering the carriage trails and elevating the barrels ever so slight. The most ingenious explanation grows out of an explosion at the Richmond arsenal in March that took it out of production for several weeks. The Army of Northern Virginia had to depend on arsenals farther south for production of many of the shells for the invasion of Pennsylvania. Confederate gunners did not realize that fuses on these shells burned more slowly than those from the Richmond arsenal; thus the shells whose fused they tried to time for explosion above front-line Union troops, showering them with lethal shrapnel, exploded a split second too late, after the shells had passed over.

On such things does history turn? McPherson tells us details like that Company F of the Twenty-Sixth North Carolina included four sets of twins, every one of whom was killed or wounded in the battle.

I’ve been to Gettysburg twice, and was pretty familiar with the shape of the events and landscape. But I’d wager this book would provide a pretty clear and readable introduction to the battle, even if you didn’t know very much about it. Certainly it’s much easier to comprehend than Shelby Foote’s Stars In The Courses, another short volume about Gettysburg, which has a poetry to it, but good luck using it to decipher what happened where.

Kinky is not a word that I love, and comedy music makes me uncomfortable. So I’ve never gotten too into Kinky Friedman. But The Great Psychedelic Armadillo Picnic: a “walk” in Austin is pretty companionable. Kinky is friends with George W. Bush, and has nothing bad to say about him (this one was published in 2004, so pre Iraq catastrophe).

There are a couple of notable omissions in this book. The coolest part of Austin to me is Rainey Street, but that section’s conversion of porched houses into bars may post-date this work. There’s also nothing about the Texas State Cemetery, which I believe is unique in the United States and tells you quite a bit about the values of Texas. Maybe worth a book of its own. Also, without explanation, Friedman tosses off that he’s never been inside the Texas Capitol Building, which is the centerpiece of Austin.

Is Austin the place of all these that has changed the most in the last twenty years?

Still, you’re on a fun ramble with a personality who’s committed to entertaining. A thin volume, thick with schtick. I really liked Kinky’s introduction to Texas history, and the stuff about the ’70s music scene. If you think calling a ghost an “Apparition-American” is funny, you’ll enjoy this book. Really, any small book about Austin in this time of home-bounditude would’ve been appreciated by me.

Compact, entertaining guides to places, by writers who really have a voice – there should be more books like this. I ate these up like cookies. Surely Boston, Los Angeles/Hollywood, Seattle, San Francisco, Savannah, Nashville, Philadelphia, Kansas City, Honolulu, Charleston could all use books like this. Brooklyn?

Hell I’d even read one about San Diego.

I’d like to write a book like this myself someday. It might be interesting to try a travel book on a smaller scale than the whole world or all of Central and South America.

Mile Marker Zero: The Moveable Feast of Key West by William McKeen

Posted: September 24, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, Florida, Hemingway, writing Leave a comment

This is a book about a scene, and the scene was Key West in the late ’60s-’70s, centered on Thomas McGuane, Jim Harrison, Hunter Thompson, Jimmy Buffett, and some lesser known but memorable characters. I tried to think of other books about scenes, and came up with Easy Riders, Raging Bulls by Peter Biskind, and maybe Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 by Ryan H. Walsh, about Van Morrison’s Boston. Then of course there’s Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, referenced here in the subtitle, a mean-spirited but often beautiful book about 1920s Paris.

I was drawn to this book after I heard Walter Kirn talking about it on Bret Easton Ellis podcast (McGuane is Kirn’s ex-father-in-law, which must be one of life’s more interesting relationships). I’ve been drawn lately to books about the actual practicalities of the writing life. How do other writers do it? How do they organize their day? What time do they get to work? What do they eat and drink? How do they avoid distraction?

From this book we learn that Jim Harrison worked until 5pm, not 4:59 but 5pm, after which he cut loose. McGuane was more disciplined, even hermitish for a time (while still getting plenty of fishing done) but eventually temptation took over, he started partying with the boys, eventually was given the chance to direct the movie from his novel 92 In The Shade. That’s when things got really crazy. The movie was not a big success.

“The Sixties” (the craziest excesses bled well into the ’70s) musta really been something.

On page one of this book I felt there was an error:

That’s not the line. The line (from the Poetry Foundation) is:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ MenGang aft agley,

Part of what these writers found special about Key West, beyond the Hemingway and Tennessee Williams legends, was it just wasn’t a regular, straight and narrow place. Being a writer is a queer job, someone’s liable to wonder what it is you do all day. In Key West, that wasn’t a problem.

Key West was so irregular and libertine that you could get away with the apparent layaboutism of the writer’s life.

Some years ago I was writing a TV pilot I’d pitched called Florida Courthouse. I went down to Florida to do some research, and people kept telling me about Key West, making it sound like Florida’s Florida. Down I went on that fantastic drive where you feel like you’re flying, over Pigeon Key, surely one of the cooler drives in the USA if not the world.

The town I found at the end of the road was truly different. Louche, kind of disgusting, and there was an element of tourists chasing a Buffett fantasy. Some of the people I encountered seemed like untrustworthy semi-pirates, and some put themselves way out to help a stranger. You’re literally and figuratively way out there, halfway to Havana. The old houses, the chickens wandering, the cemetery, the heat and the shore and the breeze and the old fort and the general sense of license and liberty has an intoxicating quality. There was a slight element of forced fun, and trying to capture some spirit that may have existed mostly in legend. McKeen captures that aspect in his book:

Like McGuane, I found the mornings in Key West to be the best attraction. Quiet, promising, unbothered, potentially productive. Then in the afternoon you could go out and see what trouble was to be found. Somebody introduced me to a former sheriff of Key West, who helped me understand his philosophy of law enforcement: “look, you can’t put that much law on people if it’s not in their hearts.”

I enjoyed my time there in this salty beachside min-New Orleans and hope to return some day, although I don’t really think I’m a Key West person in my heart. I went looking for photos from that trip, and one I found was of the Audubon House.

After finishing this book I was recounting some of the stories to my wife and we put on Jimmy Buffett radio, and that led of course to drinking a bunch of margaritas and I woke up hungover.

I rate this book: four and a half margaritas.

The illusion of choice

Posted: September 19, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, business Leave a comment

Cool graphic, from “Monopolies are Distorting the Stock Market” by Kai Wu of Sparkline Capital

Founding Documents

Posted: September 16, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, business Leave a comment

Note to readers: from time to time we accept submissions written by correspondents about topics they’re passionate about that fit into our frame of going to the source. Reader Billy Ouska sent us a writeup of something he’s passionate about, the founding documents of Facebook, and we’re proud to present it here. If you’d like to write for us, send us a pitch! – SH, editor.

The Social Network (now available to stream on Netflix) tells the story of the creation of Facebook through portrayals of the legal battles over its ownership. In a pivotal scene, cofounder Eduardo Saverin flies out to Facebook headquarters to sign some seemingly innocuous legal documents. Of course, the cut to Mark Zuckerberg watching furtively from afar tells the viewer that something is up. We later discover that Saverin has signed off on corporate restructuring that will significantly dilute his equity in the company, leading to the lawsuit whose depositions serve as a narrative device for the film. (Moral of the story: know what you’re signing! If you don’t, hire a lawyer! If there’s a lawyer in the room, ask him, “do you represent me?” If he says no, get your own guy! If he says yes, make him put it in writing!)

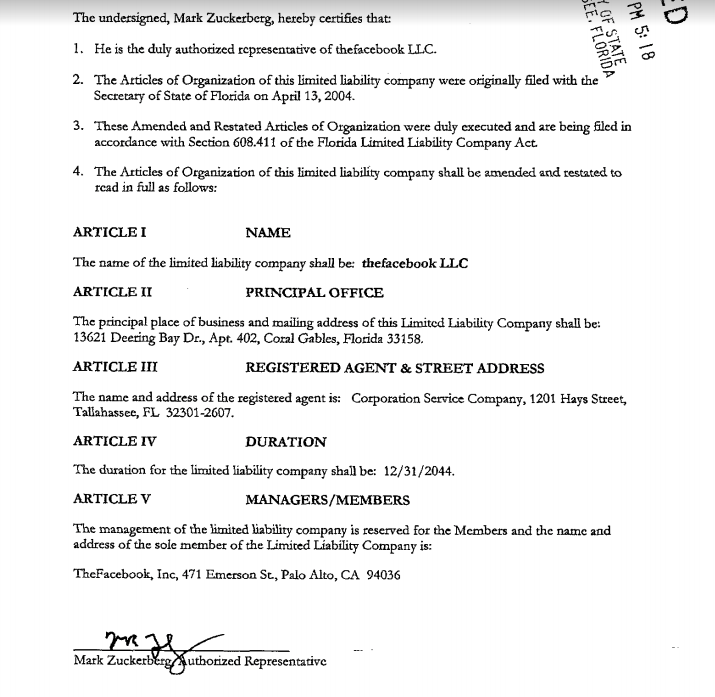

We learn that Facebook was originally formed as a Florida limited liability company and that, through legal maneuvering, another Facebook entity was created in Delaware that acquired its Florida counterpart, giving it the ability to restructure ownership. I’m not here to delve into the legal tricks that were played; other corners of the internet have already done so. Instead, I’m here to talk about something even less interesting: entity formation documents!

Formation documents (what you file with a state to create a corporation or limited liability company) are almost always available to the public. If you know the state where the entity was created, you can easily find its initial records. So, after entering “Florida entity search” into your search engine of choice, you’ll get here. With some persistence, you should be able to find information on whatever company you’re looking for, like the initial Articles of Organization of thefacebook LLC:

Maybe it’s just me, but seeing a copy of these Articles feels almost historic, and maybe a bit inspirational. Facebook is now worth hundreds of billions of dollars, but only sixteen years ago it was so green that its owners listed in a public document what look like their home addresses—no, even better, their parents’ home addresses—because they didn’t yet have an office. Mark’s address even has a typo: Dobbs Ferry is in New York, not Massachusetts. (Or, was this not a typo but rather the first of many times in which Zuckerberg would intentionally flout governmental authorities?!)

Even better is that the amended Articles of Organization are also available for viewing.

I don’t want to pull you even further into the weeds of corporate law (thanks for even making it this far!), but what I find cool here is that the amended Articles include an attachment laying out the reorganization that is signed by the man himself. Another slice of history! Think of how much impact, both positive and negative, that Facebook has had on the planet: the media industry, the outcome of the elections, the way we communicate. So much of that can be traced back to this document (and a thousand others not available for public viewing). Did Zuckerberg have any idea? Did he pause and contemplate before signing this? Did he scribble his signature without reading it, like Saverin would later do? If you squint hard enough, it can be fun to imagine the answers to these questions.

It looks like the first Articles of Organization were sent to the Florida secretary of state via fax. So, after it was run through the fax machine, the original was probably put in a file cabinet by the Organizer (Business Filings Incorporated) or thrown out. I’m guessing the amended Articles of Organization were prepared by a Palo Alto law firm, signed in Palo Alto, and then faxed or emailed to a third party in Tallahassee, which filed the documents with the Florida secretary of state. I would guess that the original in Palo Alto made its way into a client file somewhere.Even I, a noted corporate records enthusiast, don’t think that these documents need or deserve the reverence afforded to the Constitution. But I do think there is value in making them public record. Every once in a while, they give a peek behind the curtain into the workings of the corporate world, which could probably benefit from some more transparency.(PS: every state lets you access corporate records like these from the comfort of your home, though some states will require the creation of an account and/or the payment of a nominal fee to search. Just imagine what you could find!)

The Killing of Crazy Horse by Thomas Powers

Posted: September 12, 2020 Filed under: Custer, history, Indians, the American West Leave a comment

This book is fantastic. I read this like a thriller. I bought it when it came out, mainly just out of respect to the project itself. Powers took this strange and tragic incident that happened in 1877 at a dusty fort in northwestern Nebraska and produced a thick, apparently exhaustive, densely annotated book.

Crazy Horse, out of options, was persuaded to come into Camp Robinson, where it soon became clear he was going to be locked up. When he saw that he was being led into the guardhouse, he resisted, and in the struggle that followed he was stabbed. That night he died. That’s the gist of the story, what else is there to say, really?

Well, from time to time I’d open this book up and read a bit of it and always I found something curious or engaging that I wanted to know more about. Finally, summer vacation, I just decided to start at the beginning and read the whole thing.

The Little Bighorn event had my attention from when I first heard about it. Cowboys vs Indians. The setting: “a dusty Montana hillside.” A cavalry unit, wiped out to the last man. Custer, the boasting blowhard, his luck had never run out, and then it did. No survivor to tell the tale (with the exception of the alleged lone horse survivor, Comanche). The shock when the survivors of Reno’s stand a few miles away rode among the bodies days after (“how white they look!”).

The classic in this field is Son of the Morning Star, by Evan S. Connell.

How cool was Evan S.? source.

Maybe my favorite book. Connell doesn’t just tell us what happened, he follows the threads of how we might know what happened. The difficulty and ridiculousness of reconciling these accounts from often drunk, bitter, confused or otherwise untrustworthy characters of the American West.

But Powers has a great deal to add to the story. Take for example the awls of the Cheyenne. If you’ve read much about the Little Bighorn, you’ve heard that after the battle, some Cheyenne women recognized Custer’s body. They punctured his ears with what’re sometimes described as sewing needles, so he’d hear better in the next life. Here’s Powers, not just adding detail but evoking a way of life:

Every Cheyenne woman routinely carried on her person a sewing awl in a leather sheath decorated with beads or porcupine quills. The awl was used daily, for sewing clothing or lodge covers, and perhaps most frequently for keeping moccasins in repair. The moccasin soles were made of the heavy skin from a buffalo’s neck; this was the same material used for shields and it was prepared the same way – not tanned, but dried into rawhide. Pushing an awl through this hide required strength. “The making and keeping in repair of moccasins was a ceaseless task,” noted Lieutenant Clark in his notes for a book on the Indian sign language. “The last thing each day for the women was to look over the moccasins and see that each member of the family was supplied for the ensuing day.” In the many photos of the Plains Indians women taken during the nineteenth and early twentieth century their hands are notable for thickness and strength.

In the early days the awls of the Plains Indians consisted of a five- or six-inch sliver of bone, polished to a fine, slender point at one end for piercing leather, and rounded at the other to fit into the palm of the hand for pushing through tough animal hides. In later times Indian women acquired awls of steel from traders. It will be recalled that Custer’s wife, Elizabeth, had once worried that Mo-nah-se-tah would pull out a knife concealed about her person and stab her husband to death.

The Custer fight was just one occasion when Crazy Horse showed his kind of genius for cavalry battle. It looms over this story.

In a New Yorker capsule review of this book, it’s claimed:

Powers, who admits to a childhood passion for Indians, lovingly details spells and incantations—the importance of burning an offering in the proper way, even during a surprise attack; the right time to make use of a small bag of totems—but gives little insight into the larger meaning of these gestures.

This is totally ridiculous. One of the great strengths of Powers book is the care he takes with Sioux religion:

To speak of ultimate things like dying, death, and the spirit realm beyond this world, the Sioux used a kind of poetry of indeterminacy. They explained what they could and consigned the rest to a category of things humans cannot know, or had perhaps forgotten. There was no single correct way to explain these matters, and the hardest of all was to explain the wakan. Anything wakan was said to be sacred or powerful. The Oglala shaman Napsu (Finger) told a white doctor, “Anything that has a birth must have a death. The Wakan has no birth and it has no death.”

Powers never fails to help us see Crazy Horse in the context and worldview in which he saw himself.

This is a book where even the footnotes are interesting:

Now, be warned, this is a serious book. At one point I was reading it for about four hours a day and it still took me more than a week. I’m not sure this is a book for the general reader, although I’d be curious how it reads to someone who wasn’t very familiar with the Plains Indian Wars. If you’re such a reader, and you give it a try, write us!

Just the names alone: Crazy Horse’s father, who became Worm. No Water, They Are Afraid of Her, Grabber, Plenty Lice, Whirlwind, Rattle Blanket Woman.

Via an ad on Drudge Report we learn that Bill O’Reilly has a book out called Killing Crazy Horse. I doubt it will top this one. I associate O’Reilly with dishonesty and bullying, whereas Powers demonstrates in his book an integrity and devotion to taking care with the material.

Powers’ book led me to this one:

which is reigniting a passion for Ledger Art.

This is the death song Crazy Horse is said to have sung after he was wounded:

You gotta be careful or you’ll spend your whole life thinking about this stuff. People have done it!

Conversations with Faulkner

Posted: September 7, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, Hollywood, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Alcohol was his salve against a modern world he saw as a conspiracy of mediocrity on its ruling levels. Life was most bearable, he repeated, at its simplest: fishing, hunting, talking biggity in a cane chair on a board sidewalk, or horse-trading, gossiping.

Bill spoke rarely about writing, but when he did he said he had no method, no formula. He started with some local event, a well-known face, a sudden reaction to a joke or an incident. “And just let the story carry itself. I walk along behind and write down what happens.”

Origin story:

Q: Sir, I would like to know exactly what it was that inspired you to become a writer.

A: Well, I probably was born with the liking for inventing stories. I took it up in 1920. I lived in New Orleans, I was working for a bootlegger. He had a launch that I would take down the Pontchartrain into the gulf to an island where the run, the green rum, would be brought up from Cuba and buried, and we would dig it up and bring it back to New Orleans, and he would make scotch or gin or whatever he wanted. He had the bottles labeled and everything. And I would get a hundred dollars a trip for that, and I didn’t need much money, so I would get along until I ran out of money again. And I met Sherwood Anderson by chance, and we took to each other from the first. I’d meet him in the afternoon, we would walk and he would talk and I would listen. In the evening we would go somewhere to a speakeasy and drink, and he would talk and I would listen. The next morning he would say, “Well I have to work in the morning,” so I wouldn’t see him until the next afternoon. And I thought if that’s the sort of life writers lead, that’s the life for me. So I wrote a book and, as soon as I started, I found out it was fun. And I hand’t seen him and Mrs. Anderson for some time until I met her on the street, and she said, “Are you mad at us?” and I said, “No, ma’am, I’m writing a book,” and she said, “Good Lord!” I saw her again, still having fun writing the book, and she said, “Do you want Sherwood to see your book when you finish it?” and I said, “Well, I hadn’t thought about it.” She said, “Well, he will make a trade with you; if he don’t have to read that book, he will tell his publisher to take it.” I said, “Done!” So I finished the book and he told Liveright to take it and Liveright took it. And that was how I became a writer – that was the mechanics of it.

Stephen Longstreet reports on Faulkner in Hollywood, specifically To Have and Have Not:

Several other writers contributed, but Bill turned out the most pages, even if they were not all used. This made Bill a problem child.

The unofficial Writers’ Guild strawboss on the lot came to me.

“Faulkner is turning out too many pages. He sits up all night sometimes writing and turns in fifty to sixty pages in the morning. Try and speak to him.”

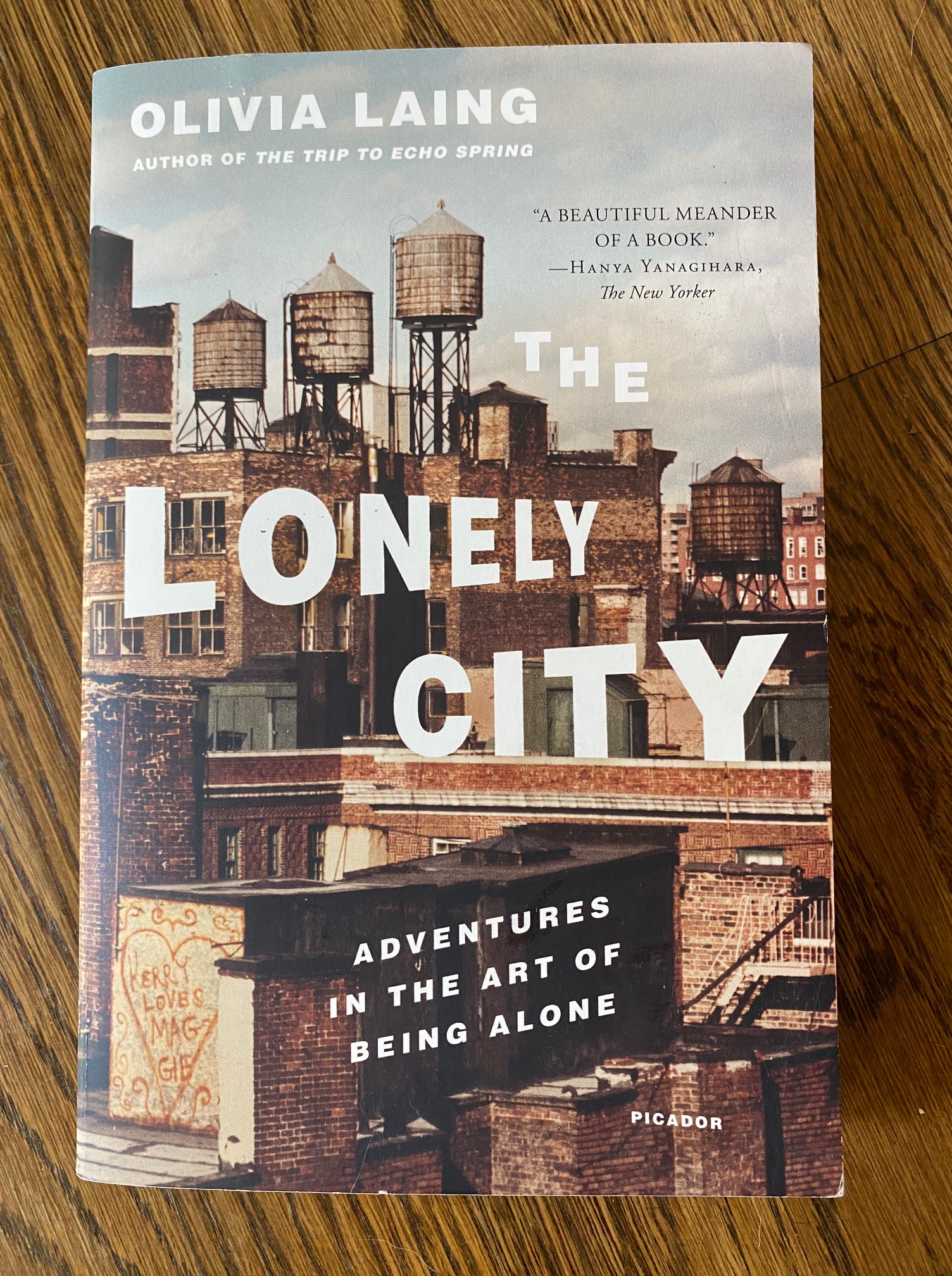

The Lonely City and The Trip To Echo Spring by Olivia Laing

Posted: September 6, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing Leave a comment

This book was great. A kind of roaming meditation on the special poignancy of urban loneliness, which is so strange and powerful because, of course, you’re around other people, even in your solitude. Also a kind of biography of Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Henry Darger, and David Wojnarowicz. (The last one I was least familiar with.)

After his mother died, Andy Warhol told people she was shopping at Bloomingdales.

Even the typeface and layout of this book is pleasing. Henry Darger’s frustrations:

A conversation with Warhol’s nephew:

As a young person I lived in New York City, and can remember from time to time feeling loneliness there. A loneliness that was almost pleasurable. Of course this comes nowhere close to the form of loneliness you might feel if you were gay and alone and dying of plague. But I felt I could connect to the feeling explored here. Laing blends her own sensations through in a way that creates something special.

When I think about loneliness in New York, the work of art that comes quickest to mind might be Nico’s These Days. I listen and I’m like yes, that’s the feeling.

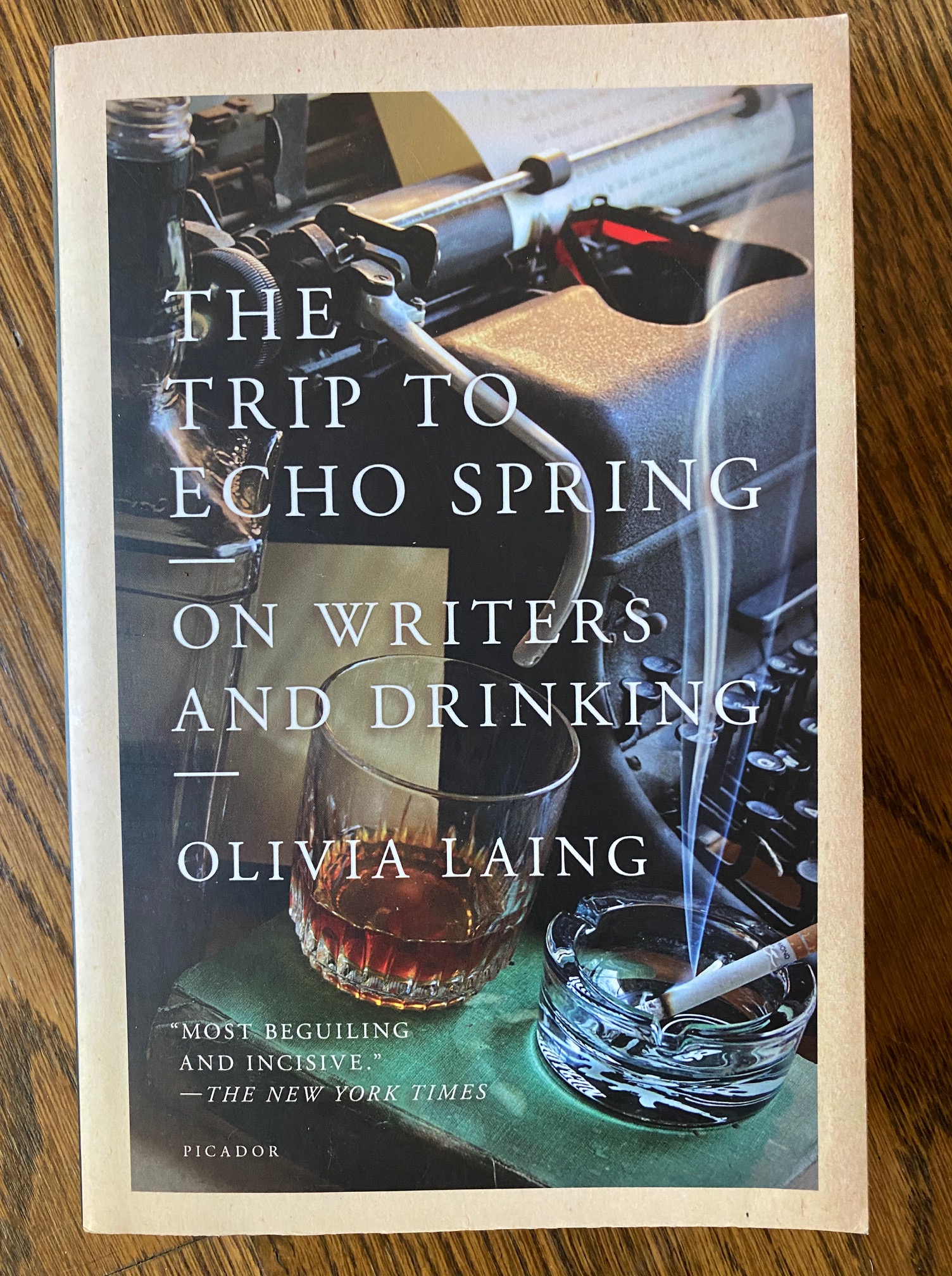

This one didn’t quite come off as much for me, maybe because I read it second, or maybe just because drinking is sort of just a sorry, depressive subject. A drunk when he’s drunk just isn’t that interesting. Laing herself (if I read the book right) isn’t an alcoholic, or even a beyond-standard English level drinker, although she discusses a history in an alcoholic household. But I didn’t feel the personal connection in quite the way I did with loneliness.

Writing in the mornings and swimming and indulging yourself in the afternoons – ideal lifestyle?

Hemingway is put on a “low alcohol diet (five ounces of whiskey and one glass of wine a day, a letter reports.”

Tennessee Williams:

in 1957 Tennessee went into psychoanalysis, and also spent a spell in what he described as a “plush-lined loony-bin” – drying out, or trying to. The seriousness with which he approached this endeavour can be gauged from his notebooks, in which he confesses day after day to “drinking a bit more than my quota.” One laconic itemisation includes: “Two Scotches at bar. 3 drinks in morning. A daiquiri at Dirty Dick’s, 3 glasses of red wine at lunch at 3 of wine at dinner – Also two Seconals so far, and a green tranquilizer whose name I do not know and a yellow one I think is called reseperine or something like that.”

The therapist was also trying to cure him of homosexuality.

I liked the parts were Laing describes the wonderful Amtrak tradition of shared tables in the dining car.

A different version of this book could’ve been called Drunk Writers and sold as like a novelty book at Urban Outfitters. Do they still sell books at Urban Outfitters?

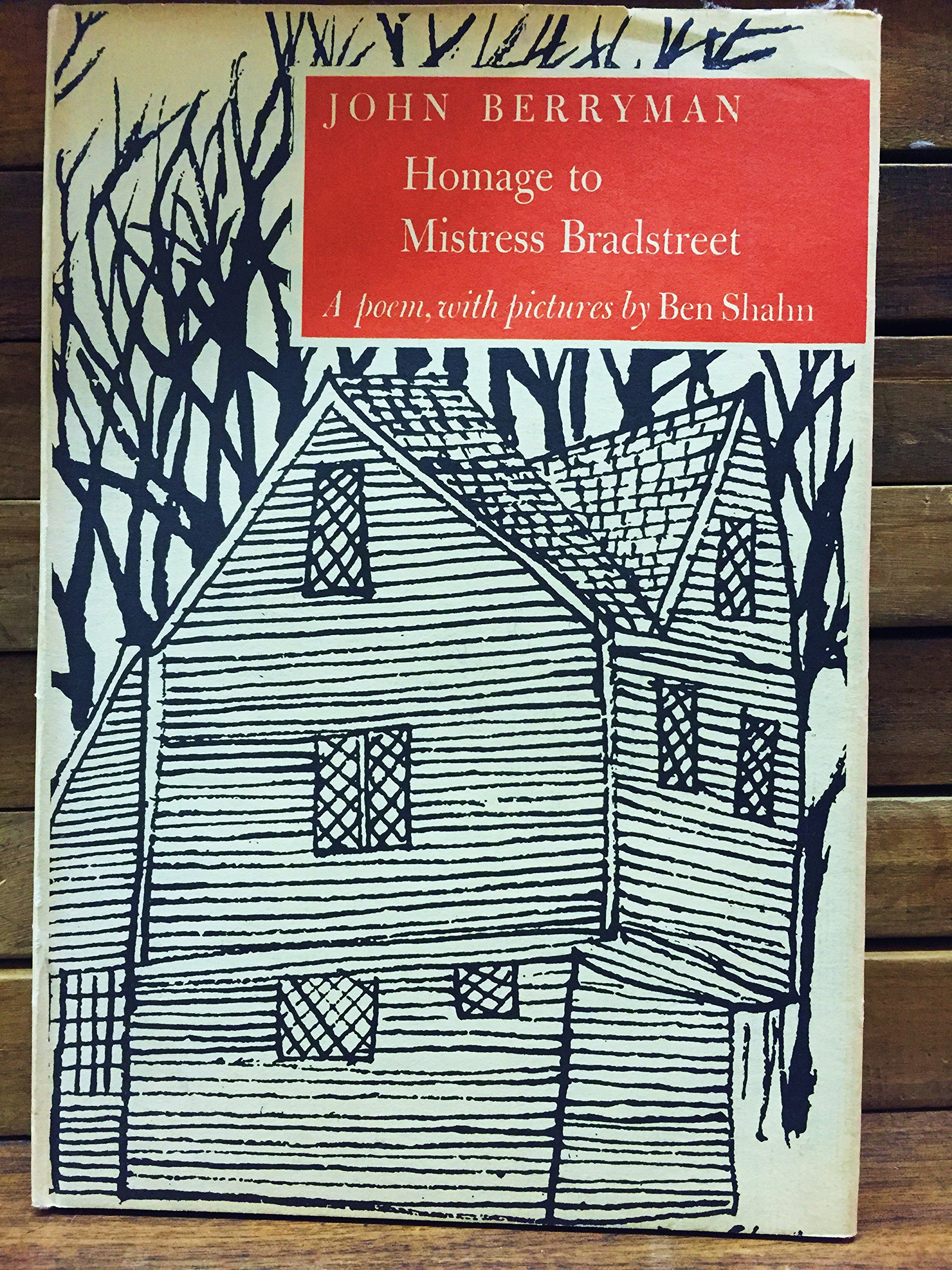

The drinker/writer Laing profiles who I knew least about was John Berryman:

Ordered a copy.

Might have to move on to To The River, about Virginia Woolf and the river Ouse.

Some iconic haircuts on Olivia Laing.

Herds

Posted: September 4, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, animals, history Leave a commentLong ago, when I was a young cowboy, I witnessed a herd reaction in a real herd – about one hundred cattle that some cowboys and I were moving from one pasture to another along a small asphalt farm-to-market road. It was mid-afternoon in mid-summer. Men, horses, and cattle were all drowsy, the herd just barely plodding along, until one cow happened to drag her hoof on the rough asphalt, making a loud rasping sound. In an instant that sleepy herd was in full flight, and our horses too. A single sound on a summer afternoon produced a short but violent stampede. The cattle and horses ran full-out for perhaps one hundred yards. It was the only stampede I was ever in, and a dragging hoof caused it.

from:

by frequent Helytimes subject Larry McMurtry. You had me at “Long ago, when I was a young cowboy.”

Oh What A Slaughter isn’t a fun book exactly, but it’s about the most friendly and conversational book you could probably find about massacres. The style of McMurtry’s non-fiction is so casual, you could argue it’s lazy or bad,

As I have several times said, massacres will out, and this one did in spades.

he says on page 80, for instance. I suspect it takes work or great practice to sound this relaxed. The book reads like the story of an old friend, even humorous at times. There’s great trust in the reader.

One point McMurtry returns to an ruminates on as a cause or at least precursor to these scenes of frenzied violence is apprehension. People get spooked. Why did a heavily armed US Army unit watching over – actually disarming – some detained Indians at Wounded Knee suddenly unleash?

The Ghost Dance might have had some kind of millennial implications, but it was just a dance helped by some poor Indians – and Indians, like the whites themselves, had always danced.

McMurtry says. Yeah, but it put the 7th Cavalry on edge, and they weren’t disciplined and controlled enough. The microsociologist Randall Collins, speaking of fights and violence generally, might’ve diagnosed what likely happened next:

Violence is not so much physical as emotional struggle; whoever achieves emotional domination, can then impose physical domination. That is why most real fights look very nasty; one sides beats up on an opponent at the time they are incapable of resisting. At the extreme, this happens in the big victories of military combat, where the troops on one side become paralyzed in the zone of 200 heartbeats per minute, massacred by victors in the 140 heartbeat range. This kind of asymmetry is especially dangerous, when the dominant side is also in the middle ranges of arousal; at 160 BPM or so, they are acting with only semi-conscious bodily control. Adrenaline is the flight-or-fight hormone; when the opponent signals weakness, shows fear, paralysis, or turns their back, this can turn into what I have called a forward panic, and the French officer Ardant du Picq called “flight to the front.” Here the attackers rush forward towards an unresisting enemy, firing uncontrollably. It has the pattern of hot rush, piling on, and overkill. Most outrageous incidents of police violence against unarmed or unresisting targets are forward panics, now publicized in our era of bullet counts and ubiquitous videos.

Conversations With series from the University Press of Mississippi

Posted: August 31, 2020 Filed under: advice, America Since 1945, Mississippi, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment This is one my favorite books, I’m serious. Shelby Foote is a great interview, obviously, just watch his interviews with Ken Burns. (“Ken, you made me a millionaire,” Shelby reports telling Burns after the series aired.) You may not want to read the whole of Shelby’s three volume Civil War, it can get carried away with the lyrical, and following the geography can be a challenge. But the flavor of it, some of the most vivid moments, and anecdotes, come through in these collected conversations with inquirers over the years.

This is one my favorite books, I’m serious. Shelby Foote is a great interview, obviously, just watch his interviews with Ken Burns. (“Ken, you made me a millionaire,” Shelby reports telling Burns after the series aired.) You may not want to read the whole of Shelby’s three volume Civil War, it can get carried away with the lyrical, and following the geography can be a challenge. But the flavor of it, some of the most vivid moments, and anecdotes, come through in these collected conversations with inquirers over the years.

“You’ve got to remember that the Civil War was as big as life,” he explains. “That’s why no historian has ever done it justice, or ever will. But that’s the glory of it. Take me: I was raised up believing Yankees were a bunch of thieves. But it’s absolutely incredible that a people could fight a Civil War and have so few atrocities.

“Sherman marched with 60,000 men slap across Georgia, then straight up though the Carolinas, burning, looting, doing everything in the world – but I don’t know of a single case of rape. That’s amazing because hatreds run high in civil wars…

There were still a lot of antique virtues around them. Jackson once told a colonel to advance his regiment across a field being riddled by bullets. When the officer protested that nobody could survive out there, Jackson told him he always took care of his wounded and buried his dead. The colonel led his troops into the field.”

Finally treated myself to a few more of these editions. These books are casual and comfortable. They’re collections of interviews from panels, newspapers, magazines, literary journals, conference discussions. Physically they’re just the right size, the printing is quality and the typeface is appealing.

Why not start with another Mississippian, someone Foote had quite a few conversations with himself?

Wow, Walker Percy could converse.

Later, different interview:

Do we dare attempt conversation with the father of them all?

I’ve long found interviews with Faulkner, even stray details from the life of Faulkner, to be more compelling than his fiction. Maybe it’s the appealing lifestyle: courtly freedom, hunting, fishing, and all the whiskey you can handle. The life of an unbothered country squire, preserving a great tradition, going to Hollywood from time to time, turning the places of your boyhood into a world mythology.

We’ll have more to say about the Conversations with Faulkner, deserves its own post! Maybe Percy gets to the heart of it in one of his interviews:

Q: Did you serve a long apprenticeship in becoming a writer?

Percy: Well, I wrote a couple of bad novels which no one wanted to buy. And I can’t imagine anyboy doing anything else. Yes it was a long apprenticeship with some frustration. But I was lucky with the third one, The Moviegoer; so, it wasn’t so bad, I guess.

Q: Had you rather be a writer than a doctor?

Percy: Let’s just say I was the happiest doctor who ever got tuberculosis and was able to quit it. It gave me an excuse to do what I wanted to do. I guess I’m like Faulkner in that respect. You know Faulkner lived for awhile in the French Quarter of New Orleans where he met Sherwood Anderson, and Faulkner used to say if anybody could live like that and get away with it he wanted to live the same way.

There’s one of these for you, I’m sure. They also have Comic Artists and Filmmakers.

only one subject with whom I myself had a conversation

For the advanced student:

Chasing The Light by Oliver Stone

Posted: August 10, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, film, movies Leave a comment 1969. Young Oliver Stone, back from Vietnam, kind of lost in his life, having barely escaped prison time for a drug charge in San Diego, enrolls at NYU’s School of the Arts, undergrad. He makes a short film in 16mm with some 8mm color intercuts, about a young veteran, played by himself, who wanders New York, and throws a bag full of his photographs off the Staten Island ferry, with a voiceover of some lines from Celine’s Journey to the End of Night.

1969. Young Oliver Stone, back from Vietnam, kind of lost in his life, having barely escaped prison time for a drug charge in San Diego, enrolls at NYU’s School of the Arts, undergrad. He makes a short film in 16mm with some 8mm color intercuts, about a young veteran, played by himself, who wanders New York, and throws a bag full of his photographs off the Staten Island ferry, with a voiceover of some lines from Celine’s Journey to the End of Night.

He shows it to his class. The professor is Martin Scorsese.

When the film ended after some eleven taut minutes and the projector was turned off, I steeled myself in the silence for the usual sarcasm consistent with our class’s Chinese Cultural Revolution “auto-critique,” in which no one was spared. What would my classmates say about this?

No one had yet spoken. Words become very important in moments like this. And Scorsese simply jumped all the discussion when he said, “Well – this is a filmmaker.” I’ll never forget that. “Why? Because it’s personal. You feel like the person who’s making it is living it,” he explained. “That’s why you gotta keep it close to you, make it yours.” No one bitched, not even the usual critiques of my weird mix, sound problems, nothing. In a sense, this was my coming out. It was the first affirmation I’d had in… years. This would be my diploma.

This book covers the first forty years of Stone’s life, with much of it centered on the making of Salvador, Platoon, and Scarface, after experiences in Vietnam and jail.

The movies of Stone’s later career – The Doors, JFK, W, Nixon – are the ones that mean the most to me, and those aren’t covered in this book. But I was still pretty compelled by it, surprised by the sensitive, easily wounded young man who emerges, experienced in violence but capable of great tenderness. Struggling with his father’s expectations, his socialite mother. His fast rise in Hollywood, frustrations and joys, and the druggy swirl that almost undoes it all, like when he gave a rambling Golden Globe acceptance speech after “a few hits of coke, a quaalude or two, several glasses of wine.” (Video of the speech since scrubbed from YouTube, unfortch).

How about Peter Guber pitching what became Midnight Express:

Make a little money for college. Innocent kid basically, knows nothing, first trip outside the country right? They beat the shit out of him! Everything in the world happens to him – and then he escapes from this island prison on a rowboat…. that’s right! A rowboat, believe it or not. Gets back to the mainland, then runs through a minefield across the Turkish border into Greece – right? Unbelievable! Great story! Tension – like you wrote Platoon. Every single second, you want to feel that tension!

The people in the next booth

Posted: August 9, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing advice from other people Leave a commentMAMET

I never try to make it hard for the audience. I may not succeed, but . . . Vakhtangov, who was a disciple of Stanislavsky, was asked at one point why his films were so successful, and he said, Because I never for one moment forget about the audience. I try to adopt that as an absolute tenet. I mean, if I’m not writing for the audience, if I’m not writing to make it easier for them, then who the hell am I doing it for? And the way you make it easier is by following those tenets: cutting, building to a climax, leaving out exposition, and always progressing toward the single goal of the protagonist. They’re very stringent rules, but they are, in my estimation and experience, what makes it easier for the audience.

INTERVIEWER

What else? Are there other rules?

MAMET

Get into the scene late, get out of the scene early.

INTERVIEWER

Why? So that something’s already happened?

MAMET

Yes. That’s how Glengarry got started. I was listening to conversations in the next booth and I thought, My God, there’s nothing more fascinating than the people in the next booth. You start in the middle of the conversation and wonder, What the hell are they talking about? And you listen heavily. So I worked a bunch of these scenes with people using extremely arcane language—kind of the canting language of the real-estate crowd, which I understood, having been involved with them—and I thought, Well, if it fascinates me, it will probably fascinate them too. If not, they can put me in jail.

from The Paris Review of course.

Really missing overhearing the people in the next booth these days. Feeling the loss of the scuttlebutt. The collective vibecheck you get from what the people you overhear in the coffeeshop, see in the elevator at work. The tide is out on that kind of info, the shared hum. When it comes back in, perceptions will change. Understandings will be recalibrated. Was wondering how this in particular with the stock market, which moves with this mood. We may find out soon!

Forty year old men in movies

Posted: August 2, 2020 Filed under: movies 1 Comment

I’ve been on this planet for forty years, and I’m no closer to understanding a single thing.

says Charlie Kaufman in Adaptation.

Forty years old, and I’ve never done a single thing I’m proud of.

says Harvey Milk, early in Milk. It’s his fortieth birthday when we meet him:

The film then flashes back to New York City in 1970, the eve of Milk’s 40th birthday and his first meeting with his much younger lover, Scott Smith.

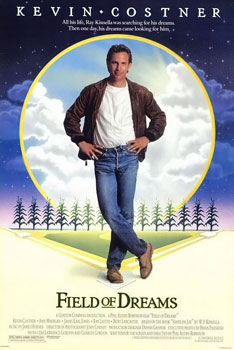

Ray Kinsella in Field of Dreams tells us he’s thirty-six:

Annie and I got married in June of ’74. Dad died that fall. A few years later, Karin was born. She smelled weird, but we loved her anyway. Then Annie got the crazy idea that she could talk me into buying a farm. I’m thirty-six years old, I love my family, I love baseball, and I’m about to become a farmer. And until I heard the Voice, I’d never done a crazy thing in my whole life.*

but that was in 1989, when, believe it or not, life expectancy was 3.89 years shorter.

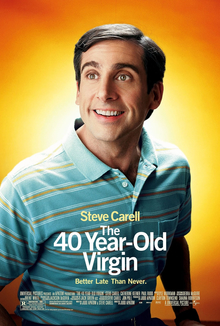

Then of course there’s:

and

What’s going on here? Is it because forty years old is about when (male) directors get the chance to make movies like this?

Are there movies about explicitly forty year old women? None leap to mind.

There are several movies about a ~ thirty year old woman’s crisis. Bridget Jones, My Best Friend’s Wedding – but I can’t think of forty year old women appearing with such clear declaration.

Could it be the actors? This is when make actors tend to be developed in their craft, at the peak of their power, empowered to wrestle with material they choose.

Is forty when a man straddles a divide between the freedom of youth and the responsibilities of adulthood? He MUST make some choice? Does that choice make for a movie?

Maybe it’s simpler than all that.

Let’s say you just turned 40. Obviously, 40 is just a number, but in many ways, it’s a milestone. Though people are living longer these days into the 80s and 90s, still age 40 is considered the halfway mark.

(That’s from this article on Seeking Alpha.)

Maybe it’s just the halfway mark. When you get to halftime you ask, how am I doing? “Make adjustments,” as the football coaches always say.

In the middle of the journey of our life

I found myself in a dark forest,

for the straight way was lost.

Not a bad way to start a story. (Dante’s Inferno, Canto I, translated by Google)

* Ray Kinsella says that before he heard the Voice, he’d “never done a crazy thing in my entire life.” But earlier in the same speech he tells us:

I marched, I smoked some grass, I tried to like sitar music,

Sounds like a guy who’s at least experimental (or is he saying he did all the cliché things of any ’60s college student?).

Ray also says that (along with Annie) he bought a farm in Iowa, the “idea” of which was, his words, “crazy.”

I think Ray protests a little too much here. I think he is the type who would at least consider a crazy thing. Perhaps that openness is part of why the Voice chose him.

One Two Three Four: The Beatles In Time by Craig Brown

Posted: July 26, 2020 Filed under: books, music, writing Leave a comment

1966. The Beatles return from the US, having played what will be their “last proper concert,” Candlestick Park, San Francisco, August 29. They have some time off.

For the first time in years, the four of them were able to take a break from being Beatles. With three months free, they could do what they liked. Ringo chose to relax at home with his wife and new baby. John went to Europe to play Private Gripweed in Richard Lester’s film How I Won The War. George flew to Bombay to study yoga and to be taught to play the sitar by Ravi Shankar. This left Paul to his own devices.

For a while he hangs out in London, where he’s surely the most famous person. It gets a tiresome, really. Paul gets the idea of going incognito. He arranges a fake mustache, and fake glasses, and slicks his hair back with Vasoline. He has an Aston Martin DB6 shipped to France, and across the Channel he goes. He drives around France for a bit, relaxing in Paris, sitting in cafes unrecognized. From his hotel window he shoots experimental film of cars passing a gendarme. On he goes.

Upon reaching Bordeaux, he felt a hankering for the night life. Still in disguise, he turned up at a local discothèque, but was refused entry. “I looked like old jerko. ‘No, no monsieur, non’ – you schmuck, we can’t let you in.” So he went back to his hotel and took off his scruffy overcoat, his moustache and his glasses. Then he returned to the disco where he was welcomed with open arms.

I absolutely hoovered up this book. I’ve read a bunch of Beatles books in the last few years: Rob Sheffield’s Dreaming The Beatles, the gossipy The Love You Make by Peter Brown and Steven Gaines, You Never Give Me Your Money by Peter Doggett, about the Beatles post Beatles. This last one may have been the most compelling, even though much of it is patient unraveling of complex business and tax situations (plus anecdotes about decadence.) A tragedy about the years the Beatles spent suing each other. Maybe because how a person handles that kind of stress – the stress of tedious meetings – is more revealing, the personalities really came to life.

You’d think I’d be bored of the Beatles. The facts of the history don’t even interest me that much, and I doubt there’s a Beatles song on my top 100 most played. I’m not that much of a Beatles fan, to be honest, not compared to the psychos. (A funny bit in this book is Craig Brown, saying he’s spent a few years in deep on Beatles books and lore, acknowledging he’s barely scratched the surface of like, people who know every version of the lineup of the Quarrymen.)

We don’t need a recounting of the basic beats of the plot of the Beatles. We know.

Craig Brown goes so far beyond that. He assumes you know the rough outlines, and somehow he breathes new life into these old bones. He makes moments pop. Specimens of time, how far can we go to recapturing them? That’s the real question of this book.

Brown will take an incident – the day Bob Dylan turned the Beatles on to marijuana, for instance – and turn it over from every angle, consider every account. How do we know what we know? Who’s telling us? What was their agenda? How much can they be trusted? The historigraphy, you might say. At the same time, he puts us right there as Brian Epstein looks at himself in the mirror, repeating a single word over and over.

Take Pete Best. You probably know that story, the original drummer, they replaced him with Ringo. The cruelty of how that went down, how the Beatles treated him, shocks here in Brown’s retelling. I didn’t know, for instance, that in 1967 Pete Best tried to kill himself. Brown takes us thereL

He locks the door, blocks any air gaps, places a pillow on the floor in front of the gas fire, and turns on the gas. He is fading way when his brother Rory arrives, smells gas, batters the door down and, screaming “Bloody idiot!” saves his life.

If you want to know what happened to the comedians who had to perform in between the Beatles’ sets on Ed Sullivan, this is the book for you.

Can I reprint all of Chapter 30?

Seems like I’m just approximating picking this book up in a bookshop. What harm in that?

Craig Brown: going on my Role Models and Inspirations board. In a random, unrelated search I learn that he is aunt by marriage to Florence Welch, of Florence + The Machine. That’s the kind of connection Craig Brown would track down and work over for any possible meaning. Maybe there’s something there, maybe he’d discard it to the flotsam of chance, who knows. The point is he’d track it down.

Brown’s 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret is great too, if you’re into The Crown type stuff.