The War Between Mochi and Sake

Posted: March 30, 2017 Filed under: art history, food, Japan, war Leave a comment

A field hospital after a battle

Posted: March 24, 2017 Filed under: Christianity, religion, war Leave a comment

US Air Force Expeditionary Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron members monitor patients during a C-17 aero-medical evacuation mission from Balad Air Base, Iraq, to Ramstein Air Base, Germany. U.S. Air Force Photo/Master Sgt. Scott Reed

Something about the health care debate got me pondering Pope Francis’ quote in a 2013 interview that the Church should be like a field hospital after a battle.

“I can clearly see that what the Church needs today is the ability to heal wounds and warm the hearts of faithful, it needs to be by their side. I see the Church as a field hospital after a battle. It’s pointless to ask a seriously injured patient whether his cholesterol or blood sugar levels are high! It’s his wounds that need to be healed. The rest we can talk about later. Now we must think about treating those wounds. And we need to start from the bottom.”

“Savage Station VA field hospital after the battle of June 27” in the Library of Congress, photographer James Gibson

There’s a lot of good writing about field hospitals after battles. Walt Whitman and Hemingway both saw some firsthand. Or how about

I never really watched MASH tbh and got kinda sad when it would come on instead of something more fun.

The Generals by Thomas Ricks

Posted: December 23, 2016 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, war, WW2 1 Comment

This book is so full of compelling anecdotes, character studies, and surprising, valuable lessons of leadership that I kind of can’t believe I got to it before Malcolm Gladwell or David Brooks or somebody scavenged it for good stories.

Generaling

Consider how hard it would be to get fifteen of your friends to leave for a road trip at the same time. How much coordination and communication it would take, how likely it was to get fucked up.

Now imagine trying to move 156,000 people across the English Channel, and you have to keep it a surprise, and on the other side there are 50,350 people waiting to try and kill you.

The Puerto Rican 65th Infantry Regiment’s bayonet charge against a Chinese division during the Korean War. Dominic D’Andrea, commissioned by the National Guard Heritage Foundation

Even at a lower scale, say a brigade, a brigadier general might oversee say 4,500 people and hundreds of vehicles. Those people must be clothed, fed, housed, their medical problems attended to. Then they have to be armed, trained, given ammo. You have to find the enemy, kill them, evacuate the wounded, stay in communication, and keep a calm head as many people are trying to kill you and the situation is changing rapidly and constantly.

32nd Brigade Command Sgt. Maj. Ed Hansen, on floor in front of podium, accepts reports from battalion command sergeants major as the brigade forms at the start of the Feb. 17 send-off ceremony at the Dane County Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Madison, Wis. Family members and public officials bade farewell to some 3,200 members of the 32nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team and augmenting units, Wisconsin Army National Guard, in the ceremony. The unit is bound for pre-deployment training at Fort Bliss, Texas, followed by a deployment of approximately 10 months for Operation Iraqi Freedom. Wisconsin Department of Military Affairs photo by Larry Sommers.

Being a general is a challenging job, I guess is my point.

U.S. Army Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, left, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and U.S. Marine Corps Gen. James N. Mattis, commander of U.S. Central Command, talk on board a C-17 while flying to Baghdad, Dec. 15, 2011. Source.

I saw this post about Gen. Mattis, possible future Secretary of Defense, on Tom Ricks blog:

A SecDef nominee at war?: What I wrote about General Mattis in ‘The Generals’

The story was so compelling that I immediately ordered Mr. Ricks’ book:

A fantastic read. Eye-opening, shocking, opinionated, compelling.

The way that Marc Norman’s book on screenwriting works as a history of Hollywood:

The Generals works as a kind of history of the US since World War II. I’d list it with 1491: New Revelations On The Americas Before Columbus as a book I think every citizen should read.

The observation that drives The Generals is this: commanding troops in combat is insanely difficult. Many generals will fail. Officers who performed well at lower ranks might completely collapse.

During World War II, generals who failed to perform were swiftly relieved of command. (Often, they were given second chances, and many stepped up).

Since World War II, swift relief of underperforming generals has not been the case. The results for American military effectiveness have been devastating. Much of this book describes catastrophe and disaster, as I guess war is even under the best of circumstances and the finest leadership.

Ricks is such a good writer, so engaging and compelling. He knows to include stuff like this:

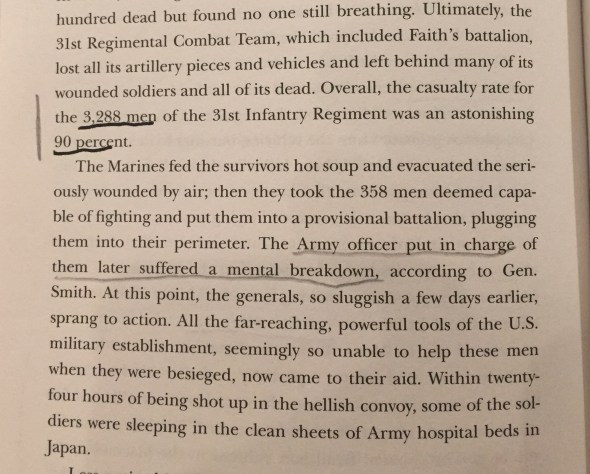

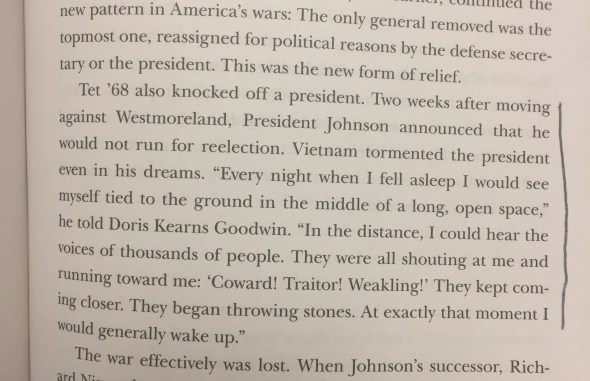

Ricks describes the catastrophes that result from bad military leadership. How about this, in Korea?:

What kind of effect did this leadership have, in Vietnam?:

He discusses the relationship of presidents and their generals:

Here is LBJ, years later, describing his nightmares:

Ricks can be blunt:

Hard lessons the Marines had learned:

Symbolically, There’s a Warning Signal Against Them as Marines Move Down the Main Line to Seoul From RG: 127 General Photograph File of the U.S. Marine Corps National Archives Identifier: 5891316 Local Identifier: 127-N-A3206

A hero in the book is O. P. Smith

who led the Marines’ reverse advance at the Chosin Resevoir, when it was so cold men’s toes were falling off from frostbite inside their boots:

The story of what they accomplished is incredible, worth a book itself. Here’s Ricks talking about the book and Smith.

A continued challenge for generals is to understand the strategic circumstances they are operating under, and the political limitations that constrain them.

031206-F-2828D-373

Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld walks with Army Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez after arriving at Baghdad International Airport in Iraq on Dec. 6, 2003. Rumsfeld is in Iraq to meet with members of the Coalition Provisional Authority, senior military leaders and the troops deployed there. DoD photo by Tech. Sgt. Andy Dunaway, U.S. Air Force. (Released) source

Recommend this book. One of the best works of military history I’ve ever read, and a sobering reflection on leadership, strategy, and the United States.

The Canny Admirals

Posted: November 30, 2016 Filed under: America Since 1945, the ocean, war, water, WW2 Leave a comment

Found this picture of John McCain Sr. (the Senator’s grandfather) and William “Bull” Halsey on Wiki while looking up something or another.

Here’s McCain Sr and Junior (the Senator’s dad) at the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay. McCain Sr. dropped dead four days later.

Microsociology

Posted: July 12, 2016 Filed under: actors, America Since 1945, how to live, sexuality, war Leave a commentHow many interesting things are in sociologist Randall Collins’ latest post (which is maybe the text of a speech or something?) Let me excerpt some for us. I have highlighted some nuggets:

I will add a parallel that is perhaps surprising. Those who know Loic Wacquant would not expect to find silent harmony. Nevertheless, Wacquant’s study of a boxing gym finds a similar pattern: there is little that boxers do in the gym that they could not do at home alone, except sparring; but in the gym they perform exercises like skipping, hitting the bags, strengthening stomach muscles, all in 3-minute segments to the ring of the bell that governs rounds in the ring. When everyone in the gym is in the same rhythm, they are animated by a collective feeling; they become boxers dedicated to their craft, not so much through minds but as an embodied project.

A large proportion of violent confrontations of all kinds– street fights, riots, etc.– quickly abort; and most persons in those situations act like Marshall’s soldiers– they let a small minority of the group do all the violence. Now that we have photos and videos of violent situations, we see that at the moment of action the expression on the faces of the most violent participants is fear. Our folk belief is that anger is the emotion of violence, but anger appears mostly before any violence happens, and in controlled situations where individuals bluster at a distant enemy. I have called thisconfrontational tension/fear; it is the confrontation itself that generates the tension, more than fear of what will happen to oneself. Confrontational tension is debilitating; phenomenologically we know (mainly from police debriefings after shootings) that it produces perceptual distortions; physiologically it generates racing heart beat, an adrenaline rush which at high levels results in loss of bodily control.

This explains another, as yet little recognized pattern: when violence actually happens, it is usually incompetent. Most of the times people fire a gun at a human target, they miss; their shots go wide, they hit the wrong person, sometimes a bystander, sometimes friendly fire on their own side. This is a product of the situation, the confrontation. We know this because the accuracy of soldiers and police on firing ranges is much higher than when firing at a human target. We can pin this down further; inhibition in live firing declines with greater distance; artillery troops are more reliable than infantry with small arms, so are fighter and bomber crews and navy crews; it is not the statistical chances of being killed or injured by the enemy that makes close-range fighters incompetent. At the other end of the spectrum, very close face-to-face confrontation makes firing even more inaccurate; shootings at a distance of less than 2 meters are extremely inaccurate. Is this paradoxical? It is facing the other person at a normal distance for social interaction that is so difficult. Seeing the other person’s face, and being seen by him or her seeing your seeing,is what creates the most tension. Snipers with telescopic lenses can be extremely accurate, even when they see their target’s face; what they do not see is the target looking back; there is no mutual attention, no intersubjectivity. Mafia hit men strike unexpectedly and preferably from behind, relying on deception and normal appearances so that there is no face confrontation. This is also why executioners used to wear hoods; and why persons wearing face masks commit more violence than those with bare faces.

NOTE THE POLICY IMPLICATION: The fashion in recent years among elite police units to wear balaclava-style face masks during their raids should be eliminated.

How does violence sometimes succeed in doing damage? The key is asymmetrical confrontation tension. One side will win if they can get their victim in the zone of high arousal and high incompetence, while keeping their own arousal down to a zone of greater bodily control. Violence is not so much physical as emotional struggle; whoever achieves emotional domination, can then impose physical domination. That is why most real fights look very nasty; one sides beats up on an opponent at the time they are incapable of resisting. At the extreme, this happens in the big victories of military combat, where the troops on one side become paralyzed in the zone of 200 heartbeats per minute, massacred by victors in the 140 heartbeat range. This kind of asymmetry is especially dangerous, when the dominant side is also in the middle ranges of arousal; at 160 BPM or so, they are acting with only semi-conscious bodily control. Adrenaline is the flight-or-fight hormone; when the opponent signals weakness, shows fear, paralysis, or turns their back, this can turn into what I have called a forward panic, and the French officer Ardant du Picq called “flight to the front.” Here the attackers rush forward towards an unresisting enemy, firing uncontrollably. It has the pattern of hot rush, piling on, and overkill. Most outrageous incidents of police violence against unarmed or unresisting targets are forward panics, now publicized in our era of bullet counts and ubiquitous videos.

Another pathway is where the fight is surrounded by an audience; people who gather to watch, especially in festive crowds looking for entertainment; historical photos of crowds watching duels; and of course the commercial/ sporting version of staged fights. This configuration produces the longest and most competent fights; confrontational tension is lowered because the fighters are concerned for their performance in the eyes of the crowd, while focusing on their opponent has an element of tacit coordination since they are a situational elite jointly performing for the audience. Even the loser in a heroic staged fight gets social support. We could test this by comparing emotional micro-behavior in a boxing match or a baseball game without any spectators.

(among the photos that come up if you Google “crowd watching a duel”:

Title: Crowd reflected in water while watching Sarazen and Ouimet duel at Weston Country Club

Beardsley vs Salazar in the 1982 Boston Marathon

Finally, there are a set of techniques for carrying out violence without face confrontation. Striking at a distance: the modern military pathway. Becoming immersed in technical details of one’s weapons rather than on the human confrontation. And a currently popular technique: the clandestine attack such as a suicide bombing, which eliminates confrontational tension because it avoids showing any confrontation until the very moment the bomb is exploded. Traditional assassinations, and the modern mafia version, also rely on the cool-headedness that comes from pretending there is no confrontation, hiding in Goffmanian normal appearances until the moment to strike.

All this sounds rather grisly, but nevertheless confrontational theory of violence has an optimistic side. First, there is good news: most threatening confrontations do not result in violence. (This is shown also in Robert Emerson’s new book on quarrels among roommates and neighbours.) We missed this because, until recently, most evidence about violence came from sampling on the dependent variable. There is a deep interactional reason why face-to-face violence is hard, not easy. Most of the time both sides stay symmetrical. Both get angry and bluster in the same way. These confrontations abort, since they can’t get around the barrier of confrontational tension. Empirically, on our micro-evidence, this zero pathway is the most common. Either the quarrel ends in mutual gestures of contempt; or the fight quickly ends when opponents discover their mutual incompetence. Curtis Jackson-Jacobs’ video analysis shows fist-fighters moving away from each other after missing with a few out-of-rhythm punches. If no emotional domination happens, they soon sense it.

More:

Anne Nassauer, assembling videos and other evidence from many angles on demonstrations, finds the turning points at which a demo goes violent or stays peaceful. And she shows that these are situational turning points, irrespective of ideologies, avowed intent of demonstrators or policing methods. Stefan Klusemann, using video evidence, shows that ethnic massacres are triggered off in situations of emotional domination and emotional passivity; that is, local conditions, apart from whatever orders are given by remote authorities. Another pioneering turning-point study is David Sorge’s analysis of the phone recording of a school shooter exchanging shots with the police, who nevertheless is calmed down by an office clerk; she starts out terrified but eventually shifts into an us-together mood that ends in a peaceful surrender. Meredith Rossner shows that restorative justice conferences succeed or fail according to the processes of interaction rituals; and that emotionally successful RJ conferences result in conversion experiences that last for several years, at least. Counter-intuitively, she finds that RJ conferences are especially likely be successful when they concerns not minor offenses but serious violence; the intensity of the ritual depends on the intensity of emotions it evokes.

High authorities are hard to study with micro methods, since organizational high rank is shielded behind very strong Goffmanian frontstages. David Gibson, however, analyzing audio tapes of Kennedy’s crisis group in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, penetrated the micro-reality of power in a situation in which all the rationally expectable scenarios led toward nuclear war. Neither JFK nor anyone else emerges as a charismatic or even a decisive leader. The group eventually muddled their way through sending signals that postponed a decision to use force, by tacitly ignoring scenarios that were too troubling to deal with. This fits the pattern that conversation analysts call the preference for agreement over disagreement, at whatever cost to rationality and consistency.

How about how social interactions affect job interviews?:

We have a long way to go to generalize these leads into a picture of how high authority really operates. Does it operate the same way in business corporations? The management literature tells us how executives have implemented well thought-out programs; but our information comes chiefly from retrospective interviews that collapse time and omit the situational process itself. Lauren Rivera cracks the veneer of elite Wall Street firms and finds that hiring decisions are made by a sense of emotional resonance between interviewer and interviewee, the solidarity of successful interaction rituals. Our best evidence of the micro details of this process comes from another arena, where Dan McFarland and colleagues analyze recorded data on speed dating, and find that conversational micro-rhythms determine who felt they “clicked” with whom.

OK what about sex?

I will end this scattered survey with some research that falls into the rubric of Weberian status groups, i.e. social rankings by lifestyle. David Grazian has produced a sequence of books,Blue Chicago and On the Make, that deal with night life. This could be considered a follow-up to Goffman’s analysis of what constitutes “fun in games” as well as “where the action is.” For Grazian, night-life is a performance of one’s “nocturnal self,” characterized by role-distance from one’s mundane day-time identity. By a combination of his own interviewing behind the scenes and collective ethnographies of students describing their evening on the town, from pre-party preparation to post-party story-telling, Grazian shows how the boys and the girls, acting as separate teams, play at sexual flirtation which for the most part is vastly over-hyped in its real results. It is the buzz of collective effervescence that some of these teams generate that is the real attraction of night life. And this may be an appropriate place to wind up. Freud, perhaps the original micro-sociologist, theorized that sexual drive is the underlying mover behind the scenes. Grazian, looking at how those scenes are enacted, finds libido as socially constructed performance. As is almost everything else.

In conclusion. Will interaction ritual, or for that matter micro-sociology as we know it, become outdated in the high-tech future? This isn’t futuristic any more, since we have been living in the era of widely dispersed information technology for at least 30 years, and we are used to its pace and direction of change. A key point for interaction ritual is that bodily co-presence is one of its ingredients. Is face contact needed? Rich Ling analyzed the everyday use of mobile phones and found that the same persons who spoke by phone a lot also met personally a lot. Cell phones do not substitute for bodily co-presence, but facilitate it. Among the most frequent back-and-forth, reciprocated connections are people coordinating where they are. Ling concluded that solidarity rituals were possible over the phone, but that they were weaker than face-to-face rituals; one was a teaser for the other.

…

Conceivably future electronic devices might wire up each other’s genitals, but what happens would likely depend on the micro-sociological theory of sex (chapter 6 in Interaction Ritual Chains): the strongest sexual attraction is not pleasure in one’s genitals per se, but getting the other person’s body to respond in mutually entraining erotic rhythms: getting turned on by getting the other person turned on. If you don’t believe me, try theorizing the attractions of performing oral sex. This is an historically increasing practice, and one of the things that drives the solidarity of homosexual movements. Gay movements are built around effervescent scenes, not around social media.

I will try theorizing the attractions of performing oral sex, Professor!

I recommend Collins’ book written with Maren McConnell, Napoleon Never Slept: How Great Leaders Leverage Social Energy, which I bought and read though I do wish there was a print edition.

Previous coverage about Collins’ work. Shoutout to Brent Forrester, who I think put me on to him.

Michael Herr

Posted: June 24, 2016 Filed under: America Since 1945, heroes, war Leave a comment

If you read Dispatches and you weren’t obsessed with learning everything you possibly could about Michael Herr, we are different!

Read it AGAIN just recently after reading Mary Karr yank out its gears and examine them in her:

Also recommended.

Just a sample of Dispatches:

What about?:

In my search for info on Herr I read this 1990 profile for the LA Times by Paul Ciotti:

Friends of friends invited him to dinner. Strangers wanted to meet him. Once, Herr recalls, he got a phone call from a guy who said he was standing in a phone booth in Nebraska in the middle of the night. “I could hear the wind blowing. He hadn’t read the book.” The caller said, “Time magazine says this. What does this mean?” Herr reversed the question: “What do you think it means?” “Oh, ho! Now that you’re rich and famous you don’t want to talk to people like me.”

:

One inspiration was Ernest Hemingway. “When I was a kid, I was obsessed with him and made some pathetic teen-age attempts to imitate him in my life. And I reinvented myself as this outdoorsman, hard-drinking and everything with it. I dare say that influence put my foot on the trail to Vietnam. Which is why that book is about acting out fantasy as much as anything.

“I had always wanted to go to war. I wanted to write a book. It was something I had to do. The networks kept referring to this as a TV war, which I didn’t believe it was. I sent a proposal to Harold Hayes. I was to write a monthly column, but once I got over there I realized this was not the way to approach the story. I wired Hayes. He said, ‘You do what you want to do. Have fun. Be careful.’ “

What do we make of this?:

What sets Herr’s book apart is the authoritative sense he conveys of the terror, ennui and ecstasy of what it felt like to be there. In a chapter about the siege of Khe Sanh, he offers a long series of conversations between two friends, a huge, gentle black Marine named Day Tripper and a little naive white Marine named Mayhew. The exchanges ring so true that one wonders, simply on a journalistic level, how he ever managed to record them.

He smiles. “They are totally fictional characters.”

They are ?

“Oh, yeah. A lot of ‘Dispatches’ is fictional. I’ve said this a lot of times. I have told people over the years that there are fictional aspects to ‘Dispatches,’ and they look betrayed. They look heartbroken, as if it isn’t true anymore. I never thought of ‘Dispatches’ as journalism. In France they published it as a novel.”

But, Herr says, “I always carried a notebook. I had this idea–I remember endlessly writing down dialogues. It was all I was really there to do. Very few lines were literally invented. A lot of lines are put into mouths of composite characters. Sometimes I tell a story as if I was present when I wasn’t, (which wasn’t difficult)–I was so immersed in that talk, so full of it and so steeped in it. A lot of the journalistic stuff I got wrong.”

My hunt for more Herr led me to this Dutch (?) documentary, First Kill, interviews with vets interspersed with film of contemporary Vietnam. Herr is interviewd first at minute 27:40 or so.

The story he tells starting around 40:20. Jeez.

I forget where I learned that Herr was living in upstate New York or sumplace, practicing a rigorous Buddhism. My trail on him brought me to this book:

What to make of this Buddhist-type idea:

On the lighter side: there’s great stuff too in Michael Herr’s book about Kubrick:

He’d tape his favorite commercials and recut them, just for the monkish exercise.

RIP.

D*-Day

Posted: June 5, 2016 Filed under: history, war, WW2 Leave a comment * the D is for Dave!

* the D is for Dave!

Happy birthday, tomorrow, June 6, to Dave King (the Great Debates co-host, not the Bad Plus drummer)

Dave King the drummer photographed by Wiki user Steve Bowbrick

A promise made in Host Chat is a promise kept so here is a selection of D-Day readings for Davis.

The single best thing to read about D-Day

is online and free. It is S. L. A. Marshall writing for The Atlantic in November, 1950.

During World War II, Marshall became an official Army combat historian, and came to know many of the war’s best-known Allied commanders, including George S. Patton and Omar N. Bradley. He conducted hundreds of interviews of both enlisted men and officers regarding their combat experiences, and was an early proponent of oral history techniques. In particular, Marshall favored the group interview, where he would gather surviving members of a frontline unit together and debrief them on their combat experiences of a day or two before.

The article is called “First Wave On Omaha Beach” here is an excerpt:

Even among some of the lightly wounded who jumped into shallow water the hits prove fatal. Knocked down by a bullet in the arm or weakened by fear and shock, they are unable to rise again and are drowned by the onrushing tide. Other wounded men drag themselves ashore and, on finding the sands, lie quiet from total exhaustion, only to be overtaken and killed by the water. A few move safely through the bullet swarm to the beach, then find that they cannot hold there. They return to the water to use it for body cover. Faces turned upward, so that their nostrils are out of water, they creep toward the land at the same rate as the tide. That is how most of the survivors make it. The less rugged or less clever seek the cover of enemy obstacles moored along the upper half of the beach and are knocked off by machine-gun fire.

Within seven minutes after the ramps drop, Able Company is inert and leaderless. At Boat No. 2, Lieutenant Tidrick takes a bullet through the throat as he jumps from the ramp into the water. He staggers onto the sand and flops down ten feet from Private First Class Leo J. Nash. Nash sees the blood spurting and hears the strangled words gasped by Tidrick: “Advance with the wire cutters!” It’s futile; Nash has no cutters. To give the order, Tidrick has raised himself up on his hands and made himself a target for an instant. Nash, burrowing into the sand, sees machine gun bullets rip Tidrick from crown to pelvis. From the cliff above, the German gunners are shooting into the survivors as from a roof top.

Captain Taylor N. Fellers and Lieutenant Benjamin R. Kearfoot never make it. They had loaded with a section of thirty men in Boat No. 6 (Landing Craft, Assault, No. 1015). But exactly what happened to this boat and its human cargo was never to be known. No one saw the craft go down. How each man aboard it met death remains unreported. Half of the drowned bodies were later found along the beach. It is supposed that the others were claimed by the sea.

After the war, Marshall would write Men Against Fire:

which claimed that only about 25% of American combat soldiers actually fired their guns at the enemy:

Marshall’s work on infantry combat effectiveness in World War II, titled Men Against Fire, is his best-known and most controversial work. In the book, Marshall claimed that of the World War II U.S. troops in actual combat, 75% never fired at the enemy for the purpose of killing, even though they were engaged in combat and under direct threat. Marshall argued that the Army should devote significant training resources to increasing the percentage of soldiers willing to engage the enemy with direct fire.

Marshall has been harshly criticized:

General Marshall said soldiers who did not fire were motivated by fear, a desire to minimize risk and a willingness, as in civilian life, to let a minority of other people carry the load.

In his 1989 memoir, About Face, Hackworth described his initial elation at an assignment with a man he idolized, and how that elation turned to disillusion after seeing Marshall’s character and methods first hand. Hackworth described Marshall as a “voyeur warrior,” for whom “the truth never got in the way of a good story” and went so far as to say, “Veterans of many of the actions he ‘documented’ in his books have complained bitterly over the years of his inaccuracy or blatant bias”.

Omaha Beach was the worst of it, but experiences on D-Day were vastly different.

stolen from the Daily Mail: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2336753/Back-beaches-final-time-D-Day-heroes-return-Normandy-mark-69th-anniversary-landings.html

Twenty-one miles away on Juno Beach the Canadian Ninth Division landed with their bikes:

Leave it to Canadians to bring their bikes. (900 Canadians died in a botched semi-practice D-Day in 1942).

Best Single Book To Read About D-Day

Looking around I can’t find my copy of Normandy Revisited by AJ Liebling:

Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS found here

Liebling, a vivacious fatso who had spent a lot of time in Normandy pre-war, describes going through with the Army and eating at spots he remembered from before. Definitely a different kind of war corresponding.

This book

was wildly popular for a reason: it’s thrilling, readable, and full of epic American hero stories.

Maybe starting with Andrew J. Higgins of Nebraska and Mobile, Alabama:

who developed shallow-draft boats for logging in the bayou (or for bootlegging?) and then took on the job of making similar boats for amphibious landings:

Anthony Beevor has a blunter take. Major takeaway from his book:

was that the Allies came up way short of their goals on D-Day. Unsurprisingly, many of those who got off the beaches in one piece considered their work done for the day. They were literally in Calvados,

it was pretty easy to find bottles of highly alcoholic apple brandy, and a lot of survivors got hammered at first opportunity.

it was pretty easy to find bottles of highly alcoholic apple brandy, and a lot of survivors got hammered at first opportunity.

Who can blame them? But the failure to achieve the ambitious goals had costs. Caen was the biggest city around:

British and Canadian troops had intended to capture the town on D-Day. However they were held up north of the city until 9 July, when an intense bombing campaign during Operation Charnwood destroyed 70% of the city and killed 2,000 French civilians.

From this Washington Post review of Beevor, some excerpts:

US Army medical services had to deal with 30,000 cases of combat exhaustion in Normandy,” and:

“Nothing . . . seemed to reduce the flow of cases where men under artillery fire would go ‘wide-eyed and jittery’, or ‘start running around in circles and crying’, or ‘curl up into little balls’, or even wander out in a trance in an open field and start picking flowers as the shells exploded. Others cracked under the strain of patrols, suddenly crying, ‘We’re going to get killed! We’re going to get killed!’ Young officers had to try to deal with ‘men suddenly whimpering, cringing, refusing to get up or get out of a foxhole and go forward under fire’. While some soldiers resorted to self-inflicted wounds, a smaller, unknown number committed suicide.”

But the single best book to read about D-Day I would say is The Boys’ Crusade by Paul Fussell:

Amazon reviewer Bill Marsano sums it up nicely:

It’s probably all that “good war” and “greatest generation” stuff that drove Fussell to write this book; he doesn’t have much truck with gooey backward glances, and that will probably make some readers mad. Well, you don’t come to Fussell–author of, among other things, “Thank God for the Atom Bomb, and Other Essays”–for good times. You come to Fussell for the hard stuff.

And here it is his contention that behind and beneath all that “greatest generation” nonsense was the Boys’ Crusade–that last year of the war in Europe when too many things went wrong too often. The generals who’d convinced themselves that this war would not be a war of attrition–i.e., human slaughter–like the last one found they’d guessed wrong. Casualties were horrifyingly high and so huge numbers of children–kids 17-19 years–old were flung into combat. And they were, with the help of the generals, ill-trained, ill-clothed and ill-equipped.

They were also faceless ciphers. As Fussell points out, the US Army’s policy was to break up training units by sending individual replacements up to the line piecemeal–one at a time–so they often arrived as strangers among strangers, often addressed merely as “Soldier” because no one knew their names. The result was too many instances of cowardice–both under fire and behind the lines–too many self-inflicted wounds to escape combat. Too many disgraces of every kind because the Army’s system, Fussell says, destroyed the most important factor in the fighting morale of the “poor bloody infantry”–the shame and fear of turning chicken in front of your comrades. Many of these boys–and Fussell is properly insistent on the word boys–funked because they had no comradeship to value.

This is not in the least a personal journal. Fussell was serriously wounded as a young second lieutenant; he was also decorated. But he wisely leaves himself out of this narrative. There’s no special pleading here, no showing of the wounds on Crispin’s Day. Instead this is a passionate but straightforward report on what that last year was like for the poor bloody infantry–those foot soldiers, those dogfaces, those 14 percent of the troops who took more than 70 percent of the casualties.

And yet there were those who stood the gaff, who survived “carnage up to and including bodies literally torn to pieces, of intestines hung on trees like Christ,mas festoons,” and managed not to dishonor themselves. They weren’t heroes, Fussell says, just men who earned the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, which was the only honor they respected. In a brief but moving passage, he explains why: It said they’d been there, been through it, and toughed it out.

Horrible as it is I found this book refreshing when I first read it, because it felt like somebody was telling me the unvarnished truth, which is that even for the good guys this was a series of catastrophes, fuckups, and massacres.

All Fussell’s books are good. This one in particular I was obsessed with:

and I talk about it in The Wonder Trail: True Stories From Los Angeles To The End Of The World, out June 14:

Those photos are by Robert Capa, who lost all but 11 of the 106 or so photos he risked his life shooting when the guy developing them was in such a hurry he fudged up the negatives.

Let’s give the last word to Fussell:

One wartime moment not at all vile occurred on June 5, 1944, when Dwight Eisenhower, entirely alone and for the moment disjunct from his publicity apparatus, changed the passive voice to active in the penciled statement he wrote out to have ready when the invasion was repulsed, his troops torn apart for nothing, his planes ripped and smashed to no end, his warships sunk, his reputation blasted: “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops.” Originally he wrote, “the troops have been withdrawn,” as if by some distant, anonymous agency instead of by an identifiable man making all-but-impossible decisions. Having ventured this bold revision, and secure in his painful acceptance of full personal accountability, he was able to proceed unevasively with “My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available.” Then, after the conventional “credit,” distributed equally to “the troops, the air, and the navy,” came Eisenhower’s noble acceptance of total personal responsibility: “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.” As Mailer says, you use the word shit so that you can use the word noble,and you refuse to ignore the stupidity and barbarism and ignobility and poltroonery and filth of the real war so thatit is mine alone can flash out, a bright signal in a dark time.

Happy Birthday Dave!

Would they like each other?

Posted: March 21, 2016 Filed under: heroes, war, writing Leave a comment

Before you say look at this fucking hipster re: Saki, remember that he was a lance sergeant in the Royal Fusiliers. Last words before he was killed by a sniper?:

Put that bloody cigarette out!

There is no grave for him, just the Thiepval monument, he is literally one of the missing of the Somme:

Shoutout to Stephen King’s 11/22/63

which sent me to Saki’s “The Open Window.”

King is such a boss. First line of his about the author:

All Roads

Posted: January 15, 2016 Filed under: America Since 1945, heroes, music, the California Condition, war Leave a comment

Happening to watch half of Jarhead on TV (Saarsgaard so good! *) leads to reading screenwriter William Broyles Jr.’s Wiki page, which leads to reading his essay “Why Men Love War”:

A lieutenant colonel I knew, a true intellectual, was put in charge of civil affairs, the work we did helping the Vietnamese grow rice and otherwise improve their lives. He was a sensitive man who kept a journal and seemed far better equipped for winning hearts and minds than for combat command. But he got one, and I remember flying out to visit his fire base the night after it had been attacked by an NVA sapper unit. Most of the combat troops I had been out on an operation, so this colonel mustered a motley crew of clerks and cooks and drove the sappers off, chasing them across tile rice paddies and killing dozens of these elite enemy troops by the light of flares. That morning, as they were surveying what they had done and loading the dead NVA–all naked and covered with grease and mud so they could penetrate the barbed wire–on mechanical mules like so much garbage, there was a look of beatific contentment on tile colonel’s face that I had not seen except in charismatic churches. It was the look of a person transported into ecstasy.

And I–what did I do, confronted with this beastly scene? I smiled back. ‘as filled with bliss as he was. That was another of the times I stood on the edge of my humanity, looked into the pit, and loved what I saw there. I had surrendered to an aesthetic that was divorced from that crucial quality of empathy that lets us feel the sufferings of others. And I saw a terrible beauty there. War is not simply the spirit of ugliness, although it is certainly that, the devil’s work. But to give the devil his due,it is also an affair of great and seductive beauty.

Which leads me to decide to finally read Chris Hedges’ book War Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning:

Chris Hedges was a graduate student in divinity at Harvard before he went to war. He spent fifteen years as a war correspondent for the Dallas Morning News, theChristian Science Monitor, and the New York Times, reporting on conflicts in El Salvador, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Iraq.

While on Amazon their robot recommends to me Ernst Jünger’s Storm Of Steel —

that’s a pass for now, but I will check out Ernst’s Wiki page:

Throughout the war, Jünger kept a diary, which would become the basis of his 1920 Storm of Steel. He spent his free time reading the works of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Ariosto andKubin, besides entomological journals he was sent from home. During 1917, he was collecting beetles in the trenches and while on patrol, 149 specimens between 2 January and 27 July, which he listed under the title of Fauna coleopterologica douchyensis (“Coleopterological fauna of the Douchy region”).

a leatherhead beetle in Death Valley illustrates the wiki page on coleopterology

which leads me to the wiki page for Wandervogel:

Wandervogel is the name adopted by a popular movement of German youth groups from 1896 onward. The name can be translated as rambling, hiking, or wandering bird (differing in meaning from “Zugvogel” or migratory bird) and the ethos is to shake off the restrictions of society and get back to nature and freedom.

which leads us both to the Japanese pastime of sawanobori, which looks semi-fun:

a bit silly but in the best way

and to History Of The Hippie Movement, subsection “Nature Boys Of Southern California” and thus to Nat King Cole’s song Nature Boy:

which has maybe the longest wiki page of any of these, culminating in

The song was a central theme in Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! “Nature Boy” was initially arranged as a techno song with singer David Bowie’s vocals, before being sent to the group Massive Attack, whose remix was used in the film’s closing credits. Bowie described the rendition as “slinky and mysterious”, adding that Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja from the group had “put together a riveting piece of work,” and that Bowie was “totally pleased with the end result.”

And just like that we’re back to Bowie.

*Saarsgaard on Catholicism:

In an interview with the New York Times, Sarsgaard stated that he followed Catholicism, saying: “I like the death-cult aspect of Catholicism. Every religion is interested in death, but Catholicism takes it to a particularly high level. […] Seriously, in Catholicism, you’re supposed to love your enemy. That really impressed me as a kid, and it has helped me as an actor. […] The way that I view the characters I play is part of my religious upbringing. To abandon curiosity in all personalities, good or bad, is to give up hope in humanity.”