Professor James McHugh sends us a good one

Posted: August 13, 2015 Filed under: heroes, writing Leave a commentJust a modest little book. That’s from The Diary of Abraham De La Pryme, the Yorkshire Antiquary. Prof. McHugh suggested reading pages 20-29, which I did and enjoyed. Some highlights:

And how about this?:

Coming soon: a review of a book about cricket!

The Tain

Posted: July 27, 2015 Filed under: Ireland, writing Leave a commentHad a couple spare minutes last night while I was waiting for some wood glue to set so I took down my copy of the Tain.

That’s pretty cool. How about this?

Things go south for her:

There’s definitely some cuts I might suggest. Do we need this?:

But there’s also some great detail:

“Two thirds more.” That precision and detail! Can’t help but think the Tain guys are having a little fun with us.

E. L. Doctorow

Posted: July 22, 2015 Filed under: America, America Since 1945, writing 1 CommentINTERVIEWER

You once told me that the most difficult thing for a writer to write was a simple household note to someone coming to collect the laundry, or instructions to a cook.

E. L. DOCTOROW

What I was thinking of was a note I had to write to the teacher when one of my children missed a day of school. It was my daughter, Caroline, who was then in the second or third grade. I was having my breakfast one morning when she appeared with her lunch box, her rain slicker, and everything, and she said, “I need an absence note for the teacher and the bus is coming in a few minutes.” She gave me a pad and a pencil; even as a child she was very thoughtful. So I wrote down the date and I started, Dear Mrs. So-and-so, my daughter Caroline . . . and then I thought, No, that’s not right, obviously it’s my daughter Caroline. I tore that sheet off, and started again. Yesterday, my child . . . No, that wasn’t right either. Too much like a deposition. This went on until I heard a horn blowing outside. The child was in a state of panic. There was a pile of crumpled pages on the floor, and my wife was saying, “I can’t believe this. I can’t believe this.” She took the pad and pencil and dashed something off. I had been trying to write the perfect absence note. It was a very illuminating experience. Writing is immensely difficult. The short forms especially.

from here of course.

The only Doctorow I read is this one, which is great:

I also read the beginning of this one:

Billy Bathgate has a lot of sexy stuff in it that I really appreciated at the time (16?). Both books start with one guy violently taking the woman of another guy as the other guy is more or less forced to watch. It’s pretty primal and intense shit. Welcome To Hard Times was even a little too much for me.

DOCTOROW

Well, it can be anything. It can be a voice, an image; it can be a deep moment of personal desperation. For instance, with Ragtime I was so desperate to write something, I was facing the wall of my study in my house in New Rochelle and so I started to write about the wall. That’s the kind of day we sometimes have, as writers. Then I wrote about the house that was attached to the wall. It was built in 1906, you see, so I thought about the era and what Broadview Avenue looked like then: trolley cars ran along the avenue down at the bottom of the hill; people wore white clothes in the summer to stay cool. Teddy Roosevelt was President. One thing led to another and that’s the way that book began: through desperation to those few images. With Loon Lake, in contrast, it was just a very strong sense of place, a heightened emotion when I found myself in the Adirondacks after many, many years of being away . . . and all this came to a point when I saw a sign, a road sign: Loon Lake. So it can be anything.

How about:

INTERVIEWER

For describing J. P. Morgan, for an example, did you spend a great deal of time in libraries?

DOCTOROW

The main research for Morgan was looking at the great photograph of him by Edward Steichen.

Google Image Search “Morgan by Edward Steichen”:

Yes to this attitude!

Posted: July 20, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing Leave a comment

Shuttin’ Up For Summer

Posted: June 28, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, heroes, writing 1 CommentTime for summer vacation here at Helytimes!

Before I go there were a couple things to get out of my system:

New David Brooks book

I like David Brooks, I’ve read all his books. Lately he’s been getting hammered by the millennials. That’s gonna happen when you tell people stuff they don’t wanna hear, true or not, and you don’t seem to actually have it all figured out yourself. Whatever, he has an exhausting job. Shouldn’t Times columnists take a year off every so often?

The message that’s at the center of this book might be, you must work hard every day at being a better person.

Who would disagree with this? Yet it’s not really a message we hear that often.

Brooks thinks people used to hear this message all the time, it was part of the public life or public religion or culture of this country. As his sparker example, he cites a radio broadcast he heard from the end of WW2:

Well, ok. But maybe they were somber because three hundred thousand American guys had gotten killed, half of Europe was leveled, China was fucked, they’d just dropped two world-changing weapons on Japan, there was footage somewhere of bodies being shoved into ditches by bulldozers at Nazi camps, and we might have to fight the Soviets tomorrow.

Maybe they were just tired and exhausted and depressed.

As for the football thing, you know durn well that’s not a fair comparison, Brooks. You’re being glib. An adrenalined athlete and a broadcast at the end of a war are going to have different tones.

Anyway. The book is mini-biographies of:

George Marshall

Francis Perkins

A. Philip Randolph

Bayard Rustin

Dorothy Day (a fox, Brooks, you should’ve mentioned that, kind of part of the story here)

George Eliot

Dwight Eisenhower

Samuel Johnson plus there’s Johnny Unitas, etc.

Those are all good. Who doesn’t love little biographies?

The basic message is that all these people worked hard to be their best, to find what that was, sort out their values and then live up to them. They overcome crazy challenges, achieved impossibilities, etc.

The world these people grew up in was very different. For one thing it was way poorer. It was way slower. It was traditional. It was segregated. Some of these people worked to change those things, others were like the embodiment of preserving those values.

So not all the lessons are easily transferable. Eisenhower and Marshall were military guys. Day worked in the Catholic tradition. Perkins and Eliot were from rigid semi-aristocracies. Maybe a moral of this book might be “use the values you’ve been taught. Lock into some tradition and try to advance it.” That’s an interesting idea.

One thing that I think is a fake claim in the Brooks book is this:

Well whatever, Joel Osteen gives me the willies, but all these characters Brooks describes believed they were “made to excel… to leave a mark on this generation… chosen, set apart”

On the whole though, the book was a fine read, and it’s worth thinking about this stuff. It reminded me of the lectures my high school headmaster used to give. There was a lot of sense in them, I look over this book of them a lot.

This is a fair slam on Brooks’ book.

When Your Enemy Wants To Surrender, Let Him.

Disappointed Brooks wrote a column about Lee without noting my and Bob Dylan’s work on the topic. As it happens I’ve been thinking about Lee a lot lately.

Grant, who’d seen thousands of people, many of them children, die horrible deaths because of Lee’s brilliance, because of his perseverance, because of his ability to inspire an army, Grant who’d lost friends and had to send his own guys to get killed by the thousands because of Lee, treated him with utmost magnanimity.

Here is what Grant says about Lee when they met at Appomattox:

The best one hour about Lee for my money is this PBS American Experience doc, avail free on my PBS Roku channel:

(How hard does American Experience dominate?)

Union General Montgomery Meigs thought of a punishment for Lee. He turned Lee’s wife’s ancestral home, to which Lee hoped to retire one day, into a fucking cemetery:

As for naming schools after him? Sure — maybe it’s a good lesson about how you can have some amazing qualities but be wrong about the most important things of your age. Kids can be reminded every day to ask “what might I be wrong about? what are we ALL wrong about?”

But also who cares? We can and should change our heroes as time goes on. Name it after the next guy. Name all those schools after Harriet Tubman or Sally Ride. Or Francis Perkins or Bayard Rustin.

Anyway: summer!

(I enjoy fails but I do prefer when I know for sure the guy isn’t paralyzed.)

If you need me btw you can find me here!:

– one of the prettiest songs ever written, says Dick Clark.

Sunday Reading

Posted: June 21, 2015 Filed under: Italy, writing Leave a commentOm Malik: I’ve been reading about you, and I have been fascinated by your progress and more importantly how you have conducted your business. Where did you find the inspiration to follow this path?

Brunello Cucinelli: From the teary eyes of my father. When we were living in the countryside, the atmosphere, the ambiance — life was good. We were just farmers, nothing special. Then he went to work in a factory. He was being humiliated and offended, and he was doing a hard job. He would not complain about the hardship or the tiny wages he received, but what he did say was, “What have I done evil to God to be subject to such humiliation?”

Basically, what is human dignity made of? If we work together, say, and, even with one look, I make you understand that you are worth nothing and I look down on you, I have killed you. But if I give you regards and respect — out of esteem, responsibility is spawned. Then out of responsibility comes creativity, because every human being has an amount of genius in them. Man needs dignity even more than he needs bread.

A correspondent sends this one along, subject line: “Most interesting thing I read today.” Fantastic:

Here, no meetings with mobile phones. No one is allowed to bring them into the meeting room. You must look me in the eye. You must know things by heart. You must know all of your business with a 1 to 2 percent error rate. It is also training for your mind. It is also a question of respect, because I have never called someone on a Saturday or a Sunday. No one is allowed to do so. We must discover this, because if individuals rest properly, then it is better.

Do you know the word otium in Latin, meaning, “doing nothing”? The Roman people were all laid back. In all the pictures, they were all laying around. They were doing nothing, just staring. In the winter on a Sunday afternoon, I can spend six hours in front of the fireplace, just looking at the flames and thinking. In the evening, I’m drunk with beautiful thoughts. My wife says to me, “What are you looking at?” I say, “The fire.” We have to take a step backward.

I’m not about to buy a $3,500 sweater but if I was it’d be from this man:

Om: What’s the correlation? All these people you are quoting are very interesting, but why mention them? Also how are they correlated to all these people whose photos you have on the wall here?

Brunello: Those are the ancient thinkers, philosophers: Socrates, Confucius, Constantine, Palladio. These people are the contemporary figures that left me with a different view on the world. Dostoyevsky, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Kafka, Kennedy and the Pope. At the end of the day, all these great people, what do they focus on? Human dignity. They all talk about being custodians in the world. Hadrian, the emperor said, “I feel responsible for the beauty in the world.”

Can I ask you, how old are you? I am 60 myself.

Om: 48.

Brunello: You are not far away from my mindset.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a great enlightened man, but he was the first of the Romantic movement, too. I think that in the last 30 years, we have tried to govern mankind through enlightenment, through the use of reason, our mind. This is no good.

This century is where enlightenment and romanticism must blend. A great idea that is born out of the mind and then goes through the soul — there is no doubt that the outcome is marvelous. If this idea is true, fair, beautiful, there’s no doubt that it is also a good idea. I think this applies to everything.

All words and pictures from this gorgeous website. There’s other great stuff. Take this, from an interview with photographer Vincent Laforet:

Om: When I was a young reporter in India, I had this one photographer friend, Anu Pushkarna. He would take the flattest pictures ever, but he was the bravest guy ever. If there was a riot or some other craziness going on, he was right in the middle of everything. It wasn’t art, but they were real. He would get hit on the head for taking a picture.The same event captured by some of the bigger-name photographers in India like Raghu Rai, the same perspective, it would be like, “Wow.” The pictures were what made the story better.

Vincent: It’s a perfect marriage. It’s like a movie, with film and sound and acting and directing and music. I wish there was more mutual respect between the different professions. I can tell you that the joke amongst war photographers has always been that most war correspondents work from their hotel rooms at the suite at the Ritz-Carlton, whereas the war photographer has to go where the bullets are flying.

AND there’s an interview with my old college nemesis! (not a bad guy, actually pretty impressive, just tragically humorless)

Hey, Readers, send me more stuff like this! I’d love to evolve Helytimes into something more like Wonderful Digest magazine, all sent in by correspondents. Helytimes’ email is helphely@gmail.

Gonna take a break for the summer soon, but send me the most interesting thing you read!

The Duke of Abruzzi

Posted: June 16, 2015 Filed under: heroes, Italy, mountains, photography, Tibet, travel, writing 2 CommentsThis one prompted me to pick up a book I’d been hearing about for awhile. Wade Davis has been featured on Helytimes before.

The opening chapter of this book is intense, vivid writing about the British experience on the Western Front during World War I. Thought I’d read enough about that horror show: Robert Graves and Paul Fussell and Geoff Dyer. Maybe the guy who hit me in the guts the hardest was Siegfried Sassoon, in part because of what a groovy idyllic life got catastrophically ruined for him.

But Wade Davis makes it all new again. One paragraph will do:

Also fascinating:

Click here if you want to see a photo of Mallory’s dead body, discovered in 1999, seventy five years after he was lost on Everest. Only halfway through Davis’ book, at the moment I’m deep in Tibet suffering along on the painstaking surveying expeditions.

A character keeps popping like a fox into the story and then disappearing — a rival mountaineer, the Duke Of Abruzzi.

(You can read about Abruzzi, why I’d be interested in a duke from there here.) What a life. Says Wiki:

He had begun to train as a mountaineer in 1892 on Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa (Italian Alps): in 1897 he made the first ascent of Mount Saint Elias (Canada/U.S., 5,489 m). There the expedition searched for a mirage, known as the Silent City of Alaska, that natives and prospectors claimed to see over a glacier. C. W. Thornton, a member of the expedition, wrote: “It required no effort of the imagination to liken it to a city, but was so distinct that it required, instead, faith to believe that it was not in reality a city.”[citation needed]

Another witness wrote in The New York Times: “We could plainly see houses, well-defined streets, and trees. Here and there rose tall spires over huge buildings which appeared to be ancient mosques or cathedrals.”

If you’re climbing K2 you’re liable to be on the Abruzzi Spur:

Late in life:

In 1918, the Duke returned to Italian Somaliland. In 1920, he founded the “Village of the Duke of Abruzzi” (Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi orVillabruzzi) some ninety kilometres north of Mogadishu. It was an agricultural settlement experimenting with new cultivation techniques. By 1926, the colony comprised 16 villages, with 3,000 Somali and 200 Italian (Italian Somalis) inhabitants. Abruzzi raised funds for a number of development projects in the town, including roads, dams, schools, hospitals, a church and a mosque. He died in the village on 18 March 1933. After Italian Somaliland was dissolved, the town was later renamed to Jowhar.

Jowhar found here, I hope user Talya doesn’t mind: http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=1569979. From wiki: “On May 17, 2009, the Islamist al-Shabab militia took of the town, and imposed draconian rules, including a ban on handshaking between men and women.”

Let’s skip to the best part of any Wikipedia page, “Personal Life:”

In the early years of the twentieth century the Abruzzi was in a relationship with Katherine Hallie “Kitty” Elkins, daughter of the wealthy American senator Stephen Benton Elkins, but the Abruzzi’s cousin King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy refused to grant him permission to marry a commoner. His brother, Emanuele Filiberto, to whom Luigi was very close, convinced him to give up the relationship.[8] His brother later approved of young Antoinette “Amber” Brizzi, the daughter of Quinto Brizzi, one of the largest vineyard owners in northern Italy. In the later years of his life, Abruzzi married a young Somali woman named Faduma Ali.

Here is a picture of the Duke of Abruzzi:

That was taken by Vittorio Sella.

The high quality of Sella’s photography was in part due to his use of 30×40 cm photographic plates, in spite of the difficulty of carrying bulky and fragile equipment into remote places. He had to invent equipment, including modified pack saddles and rucksacks, to allow these particularly large glass plates to be transported safely.[6] His photographs were widely published and exhibited, and highly praised; Ansel Adams, who saw thirty-one that Sella had presented to the US Sierra Club, said they inspired “a definitely religious awe”.

More on the Duke by Peter Bridges at VQR

More on the Duke by Peter Bridges at VQR

Hey again I just yank photos and stuff from books from all over — not sure if that’s like an ok practice but this is a non-profit site, try to credit everyone, the whole point is that maybe you will want to go look at/read the originals.

Writers in Hollywood

Posted: June 12, 2015 Filed under: actors, fscottfitzgerald, Hollywood, screenwriting, Steinbeck, the California Condition, TV, writing 1 CommentI spent the ensuing weeks across a table from Nic, hashing out plotlines. It gave me a chance to study him at close quarters. No one was more vehement about character and motivation than Nic. Now and then, he’d do the voices or act out a scene, turning his wrist to demonstrate the pop-pop of gunplay. He was 37 but somehow ageless. He could’ve stepped out of a novel by Steinbeck. The writer as crusader, chronicler of love and depravity. His shirt was rumpled, his hair mussed, his manner that of a man who’d just hiked along the railroad tracks or rolled out from under a box. He is fine-featured, with fierce eyes a little too small for his face. It gives him the aura of a bear or some other species of dangerous animal. When I was a boy and dreamed of literature, this is how I imagined a writer—a kind of outlaw, always ready to fight or go on a spree. After a few drinks, you realize the night will culminate with pledges of undying friendship or the two of you on the floor, trying to gouge each other’s eyes out.

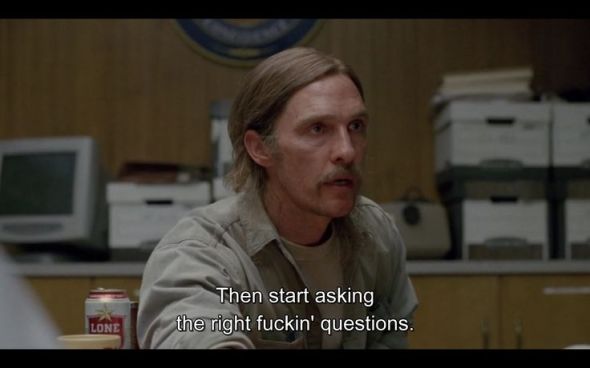

I love True Detective and I loved, loved reading this profile of Nic Pizzolatto in Vanity Fair (from which I steal the above photo, credited to Art Streiber).

I did have a quibble, though.

Here’s what profile writer Rich Cohen says about F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood:

Early in the history of film, when the big-time writers of the day, Fitzgerald most famously, were offered a role in the movies, they decided to write for the cash, forswearing deeper participation in a medium they considered second-rate. Perhaps as a result of this decision, the author came to be the forgotten figure in Hollywood, well paid but disregarded. According to the old joke, “the actress was so stupid she slept with the writer.”

Later:

Credit and power are shared. But by tossing out that first season and beginning again, Nic has a chance to finally undo the early error of Fitzgerald and the rest. If he fails and the show tanks, he’ll be just another writer with one great big freakish hit. But if he succeeds, he will have generated a model in which the stars and the stories come and go but the writer remains as guru and king.

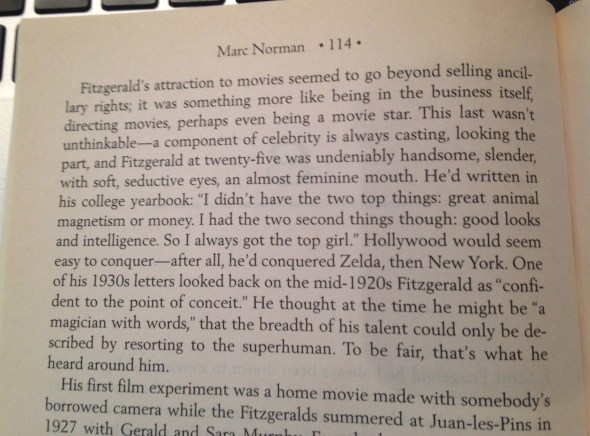

Not sure this is totally accurate. I’ve read a decent amount about F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. The more you read, the more it seems like Fitzgerald really loved Hollywood, and tried really hard to be good at writing movies, and was distressed by his failures. Fitzgerald loved movies:

When Fitzgerald worked on movies, it seems like he worked hard, was hurt when he was (frequently) fired, which sent him into tailspins that made things worse. But he was trying:

Those are from the great Marc Norman’s book, highly recommended:

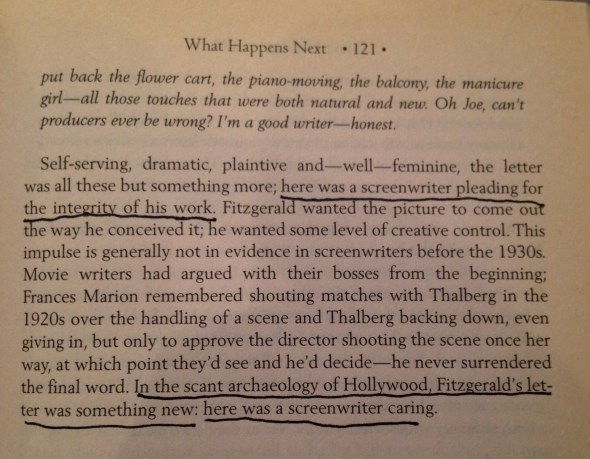

Or how about this?:

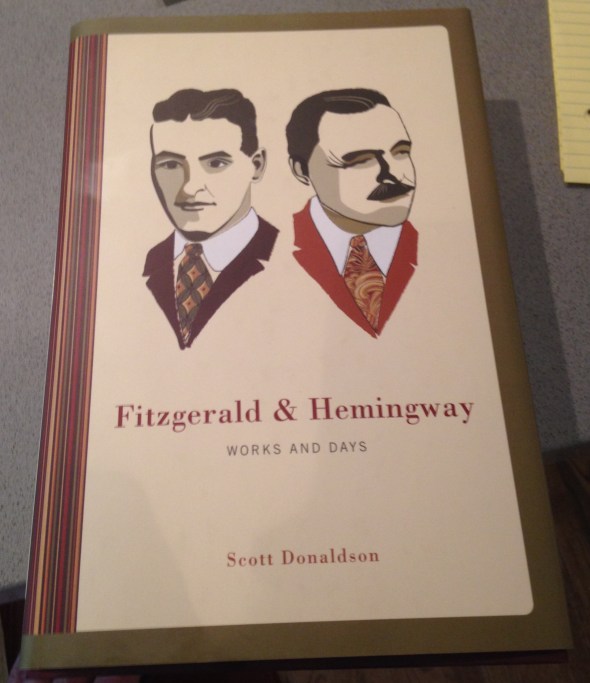

That’s from this great one, by Scott Donaldson:

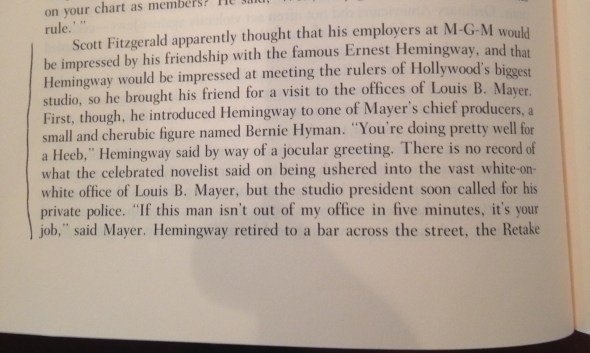

Now, that’s not to say that Fitzgerald always did everything perfectly:

(from this one, very entertaining read:

).

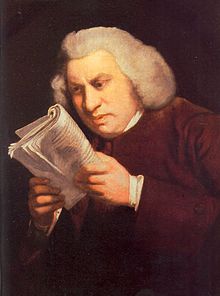

On the other hand, William Faulkner did well in Hollywood. He’s credited on at least two movies — The Big Sleep and To Have And Have Not, that you’d have to put in the all-time good list. If he’d never written a single book, you could look at those credits and call Faulkner a pretty successful screenwriter.

What did Faulkner do differently than Fitzgerald? Possibly, his secret was caring less:

Murky, to be sure.

But you might say: the big difference in the Hollywood careers of Fitzgerald and Faulkner is that Faulkner teamed with a great director, Howard Hawks, who liked him and liked working with him.

That’s what Pizzolatto did too. He teamed up with Cary Fukunaga. Cary Fukunaga directed all eight episodes of season one of True Detective (and a bunch of other things worth seeing).

Fukunaga’s not mentioned once in that Vanity Fair article. That’s crazy.

Anyway. I’m excited for season two, it sounds super interesting.

These hysterical sluts

Posted: June 9, 2015 Filed under: religion, women, writing Leave a comment Finally getting down to this one. Not all old philosophical classics are easy reading but Boethius gets off to a rip-roaring start. He’s got the Muses of Poetry at his bedside trying to cheer him up when all of a sudden Philosophy appears:

Finally getting down to this one. Not all old philosophical classics are easy reading but Boethius gets off to a rip-roaring start. He’s got the Muses of Poetry at his bedside trying to cheer him up when all of a sudden Philosophy appears:

Philosophy is like

A lot of credit is probably due to the translator, Victor Watts. He sounds like just the man for the job:

Stray Items

Posted: May 12, 2015 Filed under: Africa, America Since 1945, assorted, fscottfitzgerald, writing Leave a commentSorry I haven’t been posting more. Trying to finish my book and get Great Debates Live organized (get your tickets by emailing greatdebates69@gmail.com. We are legit almost sold out). Honestly it’s a LITTLE unfair to be mad at me for not producing enough free content.

A few items too good to ignore came across our desk:

1) Reader Robert P. in Los Angeles sends us this item:

Dear Helytimes,

Thought you might enjoy this wiki. There’s a great part about a riddle and another great part about conducting a trial. http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Numbers_Gang

Gotta say, this is one of the most intriguing Wikipedia pages I can remember. I love when Wikipedia takes myth at face value.

2) Re: our recent post about Tanya Tucker, reader Bobby M. writes:

Saw that Tanya Tucker’s Delta Dawn popped up. Love that one. We like to joke that the lyrics are a conversation wherein some jerk is taunting an insanse person. “Oh, and, Delta? Did I hear you say he was meeting you here today? And (aside to chittering friend: ‘get a load of this’) did I also hear you say he’d be taking you to his mansion. In the sky? Yeah, that’s what I thought you said, Delta. Nice flower you have on.” Midler’s version blows.

Bobby M. is one of the contributors to Lost Almanac, a truly funny print and online comedy mag.

3) We ran into reader Leila S. in New York City. She was reading the letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and sends in some highlights:

to John Peale Bishop, March, 1925, he wrote “I am quite drunk” at the top of the paper above the date, then later in the letter: “I have lost my pen so I will have to continue in pencil. It turned up– I was writing with it all the time and hadn’t noticed.”to H.L. Mencken, May 4, 1925, re: Great Gatsby:“You say, ‘the story is fundamentally trivial.'”

to Gertrude Stein, June 1925, after a long letter kissing her ass:

“Like Gatsby, I have only hope.” Dude quoted his own book he just wrote!

to Mrs. Bayard Turnbull, May 31, 1934, after a long apology about his embarrassing behavior at a tea party:“P.S. I’m sorry this is typed but I seem to have contracted Scottie’s poison ivy and my hands are swathed in bandages.”

to Joseph Hergesheimer, Fall 1935, re: Tender Is The Night“I could tell in the Stafford Bar that afternoon when you said that it was ‘almost impossible to write a book about an actress’ that you hadn’t read it thru because the actress fades out of it in the first third and is only a catalytic agent.”to Arnold Gingrich, March 20, 1936:“In my ‘Ant’ satire, the phrase ‘Lebanon School for the Blind’ should be changed to ‘New Jersey School for Drug Addicts.'” [The letter continues about other things, then at the very end, emphasis his] “Please don’t forget this change in ‘Ants.'”to Ernest Hemingway, August, 1936

“Please lay off me in print.”

As always you can reach helytimes at helphely at gmail.com

Think Piece About Mad Men

Posted: April 6, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing 1 CommentMad Men is great.

The writing is great.

The directing is great.

The actors are good.

The set decorating is great. Really colorful.

The main guy is cool and I like the stuff he does.

The other guys are funny.

The girls are hot and wear cool clothes.

There’s good stories, with surprises.

Sometimes I don’t know what’s happening but usually I figure it out or I just kinda go along.

So, I think, Mad Men is great.

James Joyce: hot or not?

Posted: March 15, 2015 Filed under: Ireland, writing Leave a commentTalking the artist as a young man, not the old blind guy. And, of course, bae (rnacle):

How about this eerie family portrait? bottom left is daughter Lucia, who got dance lessons from Isadora Duncan, fell in love with Samuel Beckett, and had Jung for a shrink (lotta good it did her):

Top right is son Giorgio. “He spent his days in an alcoholic haze,” says The New Yorker.

Top right is son Giorgio. “He spent his days in an alcoholic haze,” says The New Yorker.

Book I’m always recommending

Posted: March 11, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing 2 CommentsBill James you may know, if you read Moneyball or follow baseball. In the 1970s, while working as a nighttime security guard at a Van Camp’s pork and bean factory in Kansas, he spent his spare time researching interesting questions about baseball, writing them up, and self-publishing them:

A typical James piece posed a question (e.g.,“Which pitchers and catchers allow runners to steal the most bases?”), and then presented data and analysis written in a lively, insightful, and witty style that offered an answer.

Editors considered James’s pieces so unusual that few believed them suitable for their readers. In an effort to reach a wider audience, James self-published an annual book titled The Bill James Baseball Abstract beginning in 1977. The first edition of the book presented 80 pages of in-depth statistics compiled from James’s study of box scores from the preceding season and was offered for sale through a small advertisement in The Sporting News.

Bill James was also the last person from Kansas to be sent to Vietnam — that’s just the kind of trivia he likes to uncover, turn over, and then decide is interesting but irrelevant.

Bill James’ other passion is reading true crime books. In Popular Crime, he rounds up, summarizes, muses on what he’s learned from reading, he says, over a thousand true crime books.

This book has a fantastic table of contents, allowing you to skip about to the crimes that pique your particular interest:

It’s also written in a terrific, casual style, that trusts the reader’s common sense and intelligence. Here Bill James talking about how serial killers get caught, and a fact he’s concluded about serial killers:

Here’s an excerpt on the OJ case – chose this more or less at random to show his style:

A James question from me: why isn’t this book more popular? I think everyone I’ve recommended it to loves it, yet no one seems to have heard of it.

I’ve genuinely considered getting more into baseball just so I could read more of Bill James’ writings. It wouldn’t be right to call his style “amateurish,” but there’s something about it that’s free from professional stiffness, though I suspect it takes years of practice to sound this natural. It’s refreshing, and surprisingly rare. He’s not trying to sound like anything except himself.

Here’s an interview with James on the book conducted by Chuck Klosterman.

The (sexy) Epic Of Gilgamesh

Posted: February 26, 2015 Filed under: women, writing Leave a comment

Gilgamesh is crushing it, basically:

Gilgamesh the tall, magnificent and terrible;

who opened passes in the mountains,

who dug wells on the slopes of the uplands,

and crossed the ocean, the wide sea to the sunrise;

who scoured the world ever searching for life,

and reached through sheer force Uta-napishti the Distant;

who restored the cult-centres destroyed by the Deluge;

and set in place for the people the rites of the cosmos.

Who is there can rival his kingly standing,

and say like Gilgamesh, ‘It is I am the king’?

Gilgamesh was his name from teh day he was born,

two-thirds of him god and one third human.

But his dominance is getting to be a problem:

Though he is their shepherd and their protector,

powerful, pre-eminent, expert and mighty,

Gilgamesh lets no girl go free to her bridegroom.

So complain ‘the warrior’s daughter, the young man’s bride’ to the goddesses. So the goddess Aruru makes a man who will be a match for Gilgamesh.

In the wild she created Enkidu, the hero,

offspring of silence, knit strong by Ninurta.

All his body is matted with hair,

he bears long tresses like those of a woman:

the hair of his head grows thickly as barley,

he knows not a people, nor even a country.

Coated in hair like the god of the animals,

with the gazelles he grazes on grasses.

Joining the throng with the game at the water-hole,

his heart delighting with the beasts in the water.

Enkidu scares a hunter, who goes to Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh says “ok, go get Shamhat the temple prostitute and go tempt Enkidu”:

Then Shamhat saw him, the child of nature,

the savage man from the midst of the wild.

‘This is he, Shamhat! Uncradle your bosom,

bare your sex, let him take in your charms!

Do not recoil, but take in his scent:

he will see you, and will approach you.

Spread your clothing so he may lie on you,

do for the man the work of a woman!

Let his passion caress and embrace you,

his herd will spurn him, though he grew up amongst it.’

Shamhat unfastened the cloth of her loins,

she bared her sex and he took in her charms.

She did not recoil, she took in his scent:

she spread her clothing and he lay upon her.

She did for the man the work of a woman,

his passion caressed and embraced her.

For six days and seven nights

Enkidu was erect, as he coupled with Shamhat.

When with her delights he was fully sated,

he turned his gaze to the his herd.

The gazelles saw Enkidu, they started to run,

the beasts of the field shied away from his presence.

Enkidu had defiled his body so pure,

his legs stood still, though his herd was in motion.

Enkidu was weakened, could not run as before,

but now he had reason, and wide understanding.

Wild man fucks prostitute, loses his gazelle friends — oldest story in the world.

That’s all on Tablet One, by the way. Remember the old rule: by Tablet Two, you should have established your characters and relationships.

What happens next is Gilgamesh and Enkidu become best friends and decide to go to the Cedar Forest to kill the monster Humbaba.

Conversational fodder for your Super Bowl party

Posted: February 1, 2015 Filed under: Christianity, mysticism, religion, sports, writing 1 CommentThrowback to an old classic. Milch spins Super Bowl –> Kierkegaard. Starts around 0:41, meanders away by 3:40, pretty interesting again by 9:20 or so.

Good luck to both the Seahawks and the Patriots in returning to the spirit which gave them rise. Stand by my Super Bowl pick.

Like some…

Posted: January 27, 2015 Filed under: Texas, the American West, the California Condition, writing Leave a commentHe lives in a room above a courtyard behind a tavern and he comes down at night like some fairybook beast to fight with the sailors. (5)

The sun was just down and to the west lay reefs of bloodred clouds up out of which rose little desert nighthawks like fugitives from some great fire at the earth’s end. (23)

Then he waded out into the river like some wholly wretched baptismal candidate. (29)

The ground where he’d lain was soaked with blood and with urine from the voided bladders of animals and he went forth stained and stinking like some reeking issue of the incarnate dam of war herself. (58)

He found a clay jar of beans and some dried tortillas and he took them to a house at the end of the street where the embers of the roof were still smoldering and he warmed the food in the ashes and ate, squatting there like some deserter scavenging the ruins of a city he’d fled. (63)

Itinerant degenerates bleeding westward like some heliotropic plague. (82)

The judge sat upwind from the fire naked to the waist, himself like some pale deity, and when the black’s eyes reached his he smiled. (97)

He looked like some loutish knight beriddled by a troll. (107)

The nearest man to him was Tobin and when the black stepped out of the darkness bearing the bowieknife in both hands like some instrument of ceremony Tobin started to rise. (112)

They crossed before the sun and vanished one by one and reappeared again and they were black in the sun and they rode out of that vanished sea like burnt phantoms with the legs of the animals kicking up the spume that was not real and they were lost in the sun and lost in the lake and they shimmered and slurred together and separated again and they augmented by planes in lurid avatars and began to coalesce and there began to appear above them in the dawn-broached sky a hellish likeness of their ranks riding huge and inverted and the horses’ legs incredibly elongate trampling down the high thin cirrus and the howling antiwarriors pendant from their mounts immense and chimeric and the high wild cries carrying that flat and barren pan like the cries of souls broke through some misweave in the weft of things into the world below. (115)

Far out on the desert to the north dustspouts rose wobbling and augered the earth and some said they’d heard of pilgrims born aloft like dervishes in those mindless coils to be dropped broken and bleeding upon the desert again and there perhaps to watch the thing that had destroyed them lurch onward like some drunken djinn and resolve itself once more in the elements from which it sprang. (117)

They had but two animals and one of these had been snakebit in the desert and this thing now stood in the compound with its head enormously swollen and grotesque like some fabled equine ideation out of an Attic tragedy. (121)

The squatters stood about the dead boy with their wretched firearms at rest like some tatterdemalion guard of honor. (125)

Like some ignis fatuus belated upon the road behind them which all could see and of which none spoke. (126)

Under a gibbous moon horse and rider spanceled to their shadows on the snowblue ground and in each flare of lightning as the storm advanced those selfsame forms rearing with a terrible redundancy behind them like some third aspect of their presence hammered out black and wild upon the naked grounds. (157-8)

The dead lay awash in the shallows like the victims of some disaster at sea and they were strewn along the salt foreshore in a havoc of blood and entrails. (163)

One of the Delawares passed with a collection of heads like some strange vendor bound for market, the hair twisted about his wrist and the heads dangling and turning together. (163)

Glanton was first to reach the dying man and he knelt with that alien and barbarous head cradled between his thighs like some reeking outland nurse and dared off the savages with his revolver. (165)

All about her the dead lay with their peeled skulls like polyps bluely wet or luminescent melons cooling on some mesa of the moon. (181-2)

They passed along the ruinous walls of the cemetery where the dead were trestled up in niches and the grounds strewn with bones and skulls and broken pots like some more ancient ossuary. (182)

It was raining again and they rose slouched under slickers hacked from greasy iralfcured hides and so cowled in these primitive skins before the gray and driving rain they looked like wardens of some dim sect sent forth to proselytize among the very beasts of the land. (195)

The riders pushed between them and the rock and methodically rode them from the escarpment, the animals dropping silently as martyrs, turning sedately in the empty air and exploding on the rocks below in startling bursts of blood and silver as the flasks broke open and the mercury loomed wobbling in the air in great sheets and lobes and small trembling satellites and all its forms grouping below and racing in the stone arroyos like the imbreachment of some ultimate alchemic work decocted from out the secret dark of the earth’s heart, the fleeing stag of the ancients fugitive on the mountainside and bright and quick in the dry path of the storm channels and shaping out the sockets in the rock and hurrying from ledge to ledge down the slope shimmering and eft as eels. (203)

A mile further and he came upon a strange blackened mass in the trail like a burnt carcass of some ungodly beast. (225)

He too had lost his hat and he rode with a woven wreath of desert scrub about his head like some egregious saltland hard and he looked down upon the refugee with the same smile, as if the world were pleasing to him alone. (228)

The other heads glared blindly out of their wrinkled eyes like fellows of some righteous initiate given up to vows of silence and of death. (230)

The judge was standing on the rise in silhouette like some great balden archirnandrite. (285)

The judge in the floor of the well likewise rose and he adjusted his hat and gripped the valise under his arm like some immense and naked barrister whom the country had crazed. (296)

The idiot squatted on all fours and leaned into the lead like some naked species of lemur. (298)

When he raised his head to look out he saw the expriest stumbling among the bones and holding aloft a cross he’d fashioned out of the shins of a ram and he’d lashed them together with strips of hide and he was holding the thing before him like some mad dowser in the bleak of desert and calling out in a tongue both alien and extinct. (302)

This troubled sect traversed slowly the ground under the bluff where the watcher stood and made their way over the broken scree of a fan washed out of the draw above them and wailing and piping and clanging they passed between the granite walls into the upper valley and disappeared in the coming darkness like heralds of some unspeakable calamity leaving only bloody footprints on the stone. (326)

The candles sputtered and the great hairy mound of the bear dead in its crinoline lay like some monster slain in the commission of unnatural acts. (340)

Been re-reading this in audiobook format, blowing my mind like some mind that’s getting blown. Those page numbers, from Google books, are from the hardcover, not that paperback. (And don’t think I’m braggin’ with all those post-its on my copy — that’s the condition in which the book was returned to me after being loaned to a scholarly friend.)

Don’t miss Mills on the topic. Always worth rewatching:

Score.

Posted: January 14, 2015 Filed under: Canada, native america, writing Leave a commentSweet! A package arrived!

Let’s see what I got…

Oh, it’s Kayak Full Of Ghosts: Eskimo Tales, gathered and retold by Lawrence Millman. Let’s hear what Millman is up to:

You know what, let’s just jump right in and read one of the stories:

Ok…

Well, lots to think about. Thanks to Dan Vebber for putting me on to Millman.

Losing The War by Lee Sandlin

Posted: January 13, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing, WW2 1 Comment

Time/Life photo found here: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2016667/Colour-pictures-revealed-London-blitz-Nazi-bombers-World-War-II.html

I don’t know how I came across this essay, which was published in Chicago Review in 1999, but it’s by Lee Sandlin, an author I’d never heard of, and it was one of the best things I read in 2014.

One of the best things I’ve read about World War II ever. Insightful on government, history, human nature, memory, language. Would make this on mandatory reading for citizens, if somebody asked me. Though it’s very long (40 pages), I recommend it to you.

Hard even to pull out favorite parts but let me try:

The Greeks of Homer’s time, for instance, saw war as the one enduring constant underlying the petty affairs of humanity, as routine and all-consuming as the cycle of the seasons: grim and squalid in many ways, but still the essential time when the motives and powers of the gods are most manifest. To the Greeks, peace was nothing but a fluke, an irrelevance, an arbitrary delay brought on when bad weather forced the spring campaign to be canceled, or a back-room deal kept the troops at home until after harvest time. Any of Homer’s heroes would see the peaceful life of the average American as some bizarre aberration, like a garden mysteriously cultivated for decades on the slopes of an avalanche-haunted mountain.

found this here: http://maggiesfarm.anotherdotcom.com/index.php?url=archives/12640-Hitler-in-color.html&serendipity%5Bcview%5D=linear

One of the reasons behind the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—apart from the obvious military necessity of taking out the American fleet so that the Japanese military could conquer the western Pacific unopposed—was the unshakable conviction that Americans would collectively fold at the first sign of trouble; one big, nasty attack would be enough to get a negotiated settlement, on whatever terms the Japanese would care to name. In the same way Hitler and his inner circle were blithely sure that America would go to any lengths to stay out of the fight. Hitler’s catastrophic decision to declare war on America three days after Pearl Harbor was made almost in passing, as a diplomatic courtesy to the Japanese. To the end he professed himself baffled that America was in the war at all; he would have thought that if Americans really wanted to fight, they’d join with him against their traditional enemies, the British. But evidently they were too much under the thumb of Roosevelt—whom Hitler was positive was a Jew named Rosenfeldt, part of the same evil cabal that controlled Stalin.

As fanciful as that was, it shows the average wartime grasp of the real motives of the enemy. It was at least on a par with the American Left’s conviction that Hitler was an irrelevant puppet in the hands of the world’s leading industrialists. Throughout the war all sides regarded one another with blank incomprehension: the course of the war was distinguished by a striking absence of one of the favorite sentimental cliches of the battlefield (which was afterward said to have marked World War I)—the touching scene in the trenches where soldiers on opposed sides surreptitiously acknowledge their common humanity. For the soldiers, for the citizens at large, and for all those churning out oceans of propaganda, the enemy was a featureless mass of inscrutable, dishonorable malignity.

Here, Lee Sandlin describes the Battle of Midway, drawing on “survivors’ accounts, and from a small library of academic and military histories, ranging in scope and style from Walter Lord’s epic Miracle at Midway to John Keegan’s brilliant tactical analysis in The Price of Admiralty: The Evolution of Naval Warfare”

But the sailors on board the Japanese fleet saw things differently. They didn’t meet any American ships on June 4. That day, as on all the other days of their voyage, they saw nothing from horizon to horizon but the immensity of the Pacific. Somewhere beyond the horizon line, shortly after dawn, Japanese pilots from the carriers had discovered the presence of the American fleet, but for the Japanese sailors, the only indications of anything unusual that morning were two brief flyovers by American fighter squadrons. Both had made ineffectual attacks and flown off again. Coming on toward 10:30 AM, with no further sign of enemy activity anywhere near, the commanders ordered the crews on the aircraft carriers to prepare for the final assault on the island, which wasn’t yet visible on the horizon.

That was when a squadron of American dive-bombers came out of the clouds overhead. They’d got lost earlier that morning and were trying to make their way back to base. In the empty ocean below they spotted a fading wake—one of the Japanese escort ships had been diverted from the convoy to drop a depth charge on a suspected American submarine. The squadron followed it just to see where it might lead. A few minutes later they cleared a cloud deck and discovered themselves directly above the single largest “target of opportunity,” as the military saying goes, that any American bomber had ever been offered.

When we try to imagine what happened next we’re likely to get an image out of Star Wars—daring attack planes, as graceful as swallows, darting among the ponderously churning cannons of some behemoth of a Death Star. But the sci-fi trappings of Star Wars disguise an archaic and sluggish idea of battle. What happened instead was this: the American squadron commander gave the order to attack, the planes came hurtling down from around 12,000 feet and released their bombs, and then they pulled out of their dives and were gone. That was all. Most of the Japanese sailors didn’t even see them.

The aircraft carriers were in a frenzy just then. Dozens of planes were being refueled and rearmed on the hangar decks, and elevators were raising them to the flight decks, where other planes were already revving up for takeoff. The noise was deafening, and the warning sirens were inaudible. Only the sudden, shattering bass thunder of the big guns going off underneath the bedlam alerted the sailors that anything was wrong. That was when they looked up. By then the planes were already soaring out of sight, and the black blobs of the bombs were already descending from the brilliant sky in a languorous glide.

One bomb fell on the flight deck of the Akagi, the flagship of the fleet, and exploded amidships near the elevator. The concussion wave of the blast roared through the open shaft to the hangar deck below, where it detonated a stack of torpedoes. The explosion that followed was so powerful it ruptured the flight deck; a fireball flashed like a volcano through the blast crater and swallowed up the midsection of the ship. Sailors were killed instantly by the fierce heat, by hydrostatic shock from the concussion wave, by flying shards of steel; they were hurled overboard unconscious and drowned. The sailors in the engine room were killed by flames drawn through the ventilating system. Two hundred died in all. Then came more explosions rumbling up from below decks as the fuel reserves ignited. That was when the captain, still frozen in shock and disbelief, collected his wits sufficiently to recognize that the ship had to be abandoned.

Meanwhile another carrier, the Kaga, was hit by a bomb that exploded directly on the hangar deck. The deck was strewn with live artillery shells, and open fuel lines snaked everywhere. Within seconds, explosions were going off in cascading chain reactions, and uncontrollable fuel fires were breaking out all along the length of the ship. Eight hundred sailors died. On the flight deck a fuel truck exploded and began shooting wide fans of ignited fuel in all directions; the captain and the rest of the senior officers, watching in horror from the bridge, were caught in the spray, and they all burned to death.

Less than five minutes had passed since the American planes had first appeared overhead. The Akagi and the Kaga were breaking up. Billowing columns of smoke towered above the horizon line. These attracted another American bomber squadron, which immediately launched an attack on a third aircraft carrier, the Soryu. These bombs were less effective—they set off fuel fires all over the ship, but the desperate crew managed to get them under control. Still, the Soryu was so badly damaged it was helpless. Shortly afterward it was targeted by an American submarine (the same one the escort ship had earlier tried to drop a depth charge on). American subs in those days were a byword for military ineffectiveness; they were notorious for their faulty and unpredictable torpedoes. But the crew of this particular sub had a large stationary target to fire at point-blank. The Soryu was blasted apart by repeated direct hits. Seven hundred sailors died.

The last of the carriers, the Hiryu, managed to escape untouched, but later that afternoon it was located and attacked by another flight of American bombers. One bomb set off an explosion so strong it blew the elevator assembly into the bridge. More than 400 died, and the crippled ship had to be scuttled a few hours later to keep it from being captured.

Now there was nothing left of the Japanese attack force except a scattering of escort ships and the planes still in the air. The pilots were the final casualties of the battle; with the aircraft carriers gone, and with Midway still in American hands, they had nowhere to land. They were doomed to circle helplessly above the sinking debris, the floating bodies, and the burning oil slicks until their fuel ran out.

This was the Battle of Midway. As John Keegan writes, it was “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.” Its consequences were instant, permanent and devastating. It gutted Japan’s navy and broke its strategy for the Pacific war. The Japanese would never complete their perimeter around their new empire; instead they were thrown back on the defensive, against an increasingly large and better-organized American force, which grew surgingly confident after its spectacular victory. After Midway, as the Japanese scrambled to rebuild their shattered fleet, the Americans went on the attack. In August 1942 they began landing a marine force on the small island of Guadalcanal (it’s in the Solomons, near New Guinea) and inexorably forced a breach in the perimeter in the southern Pacific. From there American forces began fanning out into the outer reaches of the empire, cutting supply lines and isolating the strongest garrisons. From Midway till the end of the war the Japanese didn’t win a single substantial engagement against the Americans. They had “lost the initiative,” as the bland military saying goes, and they never got it back.

But it seems somehow paltry and wrong to call what happened at Midway a “battle.” It had nothing to do with battles the way they were pictured in the popular imagination. There were no last-gasp gestures of transcendent heroism, no brilliant counterstrategies that saved the day. It was more like an industrial accident. It was a clash not between armies, but between TNT and ignited petroleum and drop-forged steel. The thousands who died there weren’t warriors but bystanders—the workers at the factory who happened to draw the shift when the boiler exploded…

Akagi. There’s an interesting note here on this Navy website about why there are so few photos of the Japanese ships: http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-pac/midway/mid-4k.htm

Re: American war reporting:

What were they supposed to say about what they were seeing? At Kasserine American soldiers were blown apart into shreds of flesh scattered among the smoking ruins of exploded tanks. Ernie Pyle called this “disappointing.” Well, why not? There were no other words to describe the thing that had happened there. The truth was, the only language that seemed to register the appalling strangeness of the war was supernatural: the ghost story where nightmarish powers erupt out of nothingness, the glimpse into the occult void where human beings would be destroyed by unearthly forces they couldn’t hope to comprehend. Even the most routine event of the war, the firing of an artillery shell, seemed somehow uncanny. The launch of a shell and its explosive arrival were so far apart in space and time you could hardly believe they were part of the same event, and for those in the middle there was only the creepy whisper of its passage, from nowhere to nowhere, like a rip in the fabric of causality.

On the bureaucracy of the war:

There’s another military phrase: “in harm’s way.” That’s what everybody assumes going to war means—putting yourself in danger. But the truth is that for most soldiers war is no more inherently dangerous than any other line of work. Modern warfare has grown so complicated and requires such immense movements of men and materiel over so vast an expanse of territory that an ever-increasing proportion of every army is given over to supply, tactical support, and logistics. Only about one in five of the soldiers who took part in World War II was in a combat unit (by the time of Vietnam the ratio in the American armed forces was down to around one in seven). The rest were construction workers, accountants, drivers, technicians, cooks, file clerks, repairmen, warehouse managers—the war was essentially a self-contained economic system that swelled up out of nothing and covered the globe.

For most soldiers the dominant memory they had of the war was of that vast structure arching up unimaginably high overhead. It’s no coincidence that two of the most widely read and memorable American novels of the war, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, are almost wholly about the cosmic scale of the American military’s corporate bureaucracy and mention Hitler and the Nazis only in passing. Actual combat could seem like almost an incidental side product of the immense project of military industrialization. A battle for most soldiers was something that happened up the road, or on the fogbound islands edging the horizon, or in the silhouettes of remote hilltops lit up at night by silent flickering, which they mistook at first for summer lightning. And when reporters traveled through the vast territories under military occupation looking for some evidence of real fighting, what they were more likely to find instead was a scene like what Martha Gellhorn, covering the war for Collier’s, discovered in the depths of the Italian countryside: “The road signs were fantastic….The routes themselves, renamed for this operation, were marked with the symbols of their names, a painted animal or a painted object. There were the code numbers of every outfit, road warnings—bridge blown, crater mines, bad bends—indications of first-aid posts, gasoline dumps, repair stations, prisoner-of-war cages, and finally a marvelous Polish sign urging the troops to notice that this was a malarial area: this sign was a large green death’s-head with a mosquito sitting on it.”

That was the war: omnipresent, weedlike tendrils of contingency and code spreading over a landscape where the battle had long since passed.

It was much the same in the U.S. The bureaucracy of war became an overpowering presence in people’s lives, even though the reality of battle was impossibly remote. Prices were controlled by war-related government departments, nonessential nonmilitary construction required a nightmare of paperwork, food and gas were rationed—any long-distance car travel that wasn’t for war business meant a special hearing before a ration board, and almost every train snaking through the depths of the heartland had been commandeered for classified military transport. The necessities of war even broke up the conventional proprieties of marriage: the universal inevitability of military service meant that young couples got married quickly, sometimes at first meeting—and often only so the women could get the military paycheck and the ration stamps.

The war was the single dominant fact in the world, saturating every radio show and newspaper. Every pennant race was described on the sports pages in the metaphor of battle; every car wreck and hotel fire was compared to the air raids that everyone was still expecting to hit the blacked-out cities on the coasts.

But who was controlling the growth of this fantastic edifice? Nobody could say. People who went to Washington during those years found a desperately overcrowded town caught up in a kind of diffuse bureaucratic riot. New agencies and administrations overflowed from labyrinthine warrens of temporary office space. People came to expect that the simplest problem would lead to hours or days of wandering down featureless corridors, passing door after closed door spattered by uncrackable alphabetic codes: OPA, OWI, OSS. Nor could you expect any help or sympathy once you found the right office: if the swarms of new government workers weren’t focused on the latest crisis in the Pacific, they were distracted by the hopeless task of finding an apartment or a boarding house or a cot in a spare room. Either way, they didn’t give a damn about solving your little squabble about petroleum rationing.

It might have been some consolation to know that people around the world were stuck with exactly the same problems—particularly people on the enemy side. There was a myth (it still persists) that the Nazi state was a model of efficiency; the truth was that it was a bureaucratic shambles. The military functioned well—Hitler gave it a blank check—but civilian life was made a misery by countless competing agencies and new ministries, all claiming absolute power over every detail of German life. Any task, from getting repairs in an apartment building to requisitioning office equipment, required running a gauntlet of contradictory regulations. One historian later described Nazi Germany as “authoritarian anarchy.”

But then everything about the war was ad hoc and provisional. The British set up secret installations in country estates; Stalin had his supreme military headquarters in a commandeered Moscow subway station. Nobody cared about making the system logical, because everything only needed to happen once. Every battle was unrepeatable, every campaign was a special case. The people who were actually making the decisions in the war—for the most part, senior staff officers and civil service workers who hid behind anonymous doors and unsigned briefing papers—lurched from one improvisation to the next, with no sense of how much the limitless powers they were mustering were remaking the world.

But there was one constant. From the summer of 1942 on, the whole Allied war effort, the immensity of its armies and its industries, were focused on a single overriding goal: the destruction of the German army in Europe. Allied strategists had concluded that the global structure of the Axis would fall apart if the main military strength of the German Reich could be broken. But that task looked to be unimaginably difficult. It meant building up an overwhelmingly large army of their own, somehow getting it on the ground in Europe, and confronting the German army at point-blank range. How could this possibly be accomplished? The plan was worked out at endless briefings and diplomatic meetings and strategy sessions held during the first half of 1942. The Soviet Red Army would have to break through the Russian front and move into Germany from the east. Meanwhile, a new Allied army would get across the English Channel and land in France, and the two armies would converge on Berlin.

The plan set the true clock time of the war. No matter what the surface play of battle was in Africa or the South Seas, the underlying dynamic never changed: every hour, every day the Allies were preparing for the invasion of Europe. They were stockpiling thousands of landing craft, tens of thousands of tanks, millions upon millions of rifles and mortars and howitzers, oceans of bullets and bombs and artillery shells—the united power of the American and Russian economies was slowly building up a military force large enough to overrun a continent. The sheer bulk of the armaments involved would have been unimaginable a few years earlier. One number may suggest the scale. Before the war began the entire German Luftwaffe consisted of 4,000 planes; by the time of the Normandy invasion American factories were turning out 4,000 new planes every two weeks.

Kursk tanks, found here: http://www.battleofkursk.org/Battle-of-Kursk-Tanks.html

On how much crazier the Eastern Front was:

In August 1943, for instance, in the hilly countryside around the town of Kursk (about 200 miles south of Moscow), the German and Soviet armies collided in an uncontrolled slaughter: more than four million men and thousands of tanks desperately maneuvered through miles of densely packed minefields and horizon-filling networks of artillery fire. It may have been the single largest battle fought in human history, and it ended—like all the battles on the eastern front—in a draw.

On an uncanny force driving war through history:

In the First Book of Maccabees it’s written that Alexander the Great “made many wars, and won many strongholds, and slew the kings of the earth, and went through to the ends of the earth, and took spoils of many nations, insomuch that the earth was quiet before him.” Uncharacteristically for the Bible, there is no moral judgment offered on the way Alexander chose to pass his time. Maybe this is because there couldn’t be. There are certain people whose lives are so vastly out of scale with the rest of humanity, whether for good or evil, that the conventional verdicts seem foolish. Alexander, like Genghis Khan or Napoleon, was born to be a world wrecker. He single-handedly brought down the timeless empires of pagan antiquity and turned names like Babylon and Persia into exotic, dim legends. His influence was so dramatic and pervasive that people were still talking about him as the dominant force in the world centuries after he was dead. The writers of the Apocrypha knew that he was somehow responsible for the circumstances that led to the Maccabean revolt, even though he’d never set foot in Judea. The Romans knew that their empire was possible only because it was built out of the wreckage Alexander had left behind him in the Middle East. We know that Western civilization is arranged the way it is in large part because Alexander destroyed the civilizations that came before it.

But why had he done it? The author of Maccabees received no divine insight on that score. Nobody did. Even the people who actually knew Alexander were baffled by him. According to all the biographies and versified epics about him that have survived from the ancient world, his friends and subordinates found him almost impossible to read. He never talked about what he wanted or whether there was any conquest that would finally satisfy him; he never revealed the cause of the unappeasable sense of grievance that led him to take on the kings of the earth. Yet his peculiar manner led a lot of people in his entourage to think that he was somehow in touch with divine forces. He frequently had an air of trancelike distraction, as though his brilliant military strategies were dictated by some mysterious inner voice, and he had a habit of staring not quite at people but just over their shoulder, as though he were picking up some ethereal presence in the room invisible to everybody else. But even without these signs, people were bound to think that he was fulfilling a god’s unknowable whims. After all, what he was doing made no sense in human terms: it was global destruction for its own sake, and what mortal could possibly want that?

“Pilots pleased over their victory during the Marshall Islands attack, grin across the tail of an F6F Hellcat on board the USS LEXINGTON, after shooting down 17 out of 20 Japanese planes heading for Tarawa.” Comdr. Edward Steichen, November 1943. 80-G-470985. (ww2_75.jpg, National Archives)

How about this, on the Old Norse vocabulary of war:

Another Viking term was “fey.” People now understand it to mean effeminate. Previously it meant odd, and before that uncanny, fairylike. That was back when fairyland was the most sinister place people could imagine. The Old Norse word meant “doomed.” It was used to refer to an eerie mood that would come over people in battle, a kind of transcendent despair. The state was described vividly by an American reporter, Tom Lea, in the midst of the desperate Battle of Peleliu in the South Pacific. He felt something inside of himself, some instinctive psychic urge to keep himself alive, finally collapse at the sight of one more dead soldier in the ruins of a tropical jungle: “He seemed so quiet and empty and past all the small things a man could love or hate. I suddenly knew I no longer had to defend my beating heart against the stillness of death. There was no defense.”

There was no defense—that’s fey. People go through battle willing the bullet to miss, the shelling to stop, the heart to go on beating—and then they feel something in their soul surrender, and they give in to everything they’ve been most afraid of. It’s like a glimpse of eternity. Whether the battle is lost or won, it will never end; it has wholly taken over the soul. Sometimes men say afterward that the most terrifying moment of any battle is seeing a fey look on the faces of the soldiers standing next to them.

But the fey becomes accessible to civilians in a war too—if the war goes on long enough and its psychic effects become sufficiently pervasive. World War II went on so long that both soldiers and civilians began to think of feyness as a universal condition. They surrendered to that eternity of dread: the inevitable, shattering resumption of an artillery barrage; the implacable cruelty of an occupying army; the panic, never to be overcome despite a thousand false alarms, at an unexpected knock on the door, or a telegram, or the sight out the front window of an unfamiliar car pulling to a halt. They got so used to the war they reached a state of acquiescence, certain they wouldn’t stop being scared until they were dead.

It was in a fey mood that, in the depths of the German invasion, Russian literary scholar Mikhail Bakhtin took the only copy of his life’s work, a study of Goethe, and ripped it up, page by page and day by day, for that unobtainable commodity, cigarette paper.

“USS SHAW exploding during the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor.” December 7, 1941. 80-G-16871. From the National Archives

A feyness of bureaucracy:

A rational calculation of the odds is a calculation by the logic of peace. War has a different logic. A kind of vast feyness can infect a military bureaucracy when it’s losing a war, a collective slippage of the sense of objective truth in the face of approaching disaster. In the later years of World War II the bureaucracies of the Axis—partially in Germany, almost wholly in Japan—gave up any pretense of realism about their situation. Their armies were fighting all over the world with desperate berserker fury, savagely contesting every inch of terrain, hurling countless suicide raids against Allied battalions (kamikaze attacks on American ships at Okinawa came in waves of a hundred planes at a time)—while the bureaucrats behind the lines gradually retreated into a dreamy paper war where they were on the brink of a triumphant reversal of fortune.

They had the evidence. Officers in the field, unable to face or admit the imminence of defeat, routinely submitted false reports up the chain of command. Commanders up the line were increasingly prone to believe them, or to pretend to believe them. And so, as the final catastrophe approached, strategists in both Berlin and Tokyo could be heard solemnly discussing the immense weight of paper that documented the latest round of imaginary victories, the long-overrun positions that they still claimed to hold, and the Allied armies and fleets that had just been conclusively destroyed—even though the real-world Allied equivalents had crashed through the lines and were advancing toward the homeland.

“Two bewildered old ladies stand amid the leveled ruins of the almshouse which was Home; until Jerry dropped his bombs. Total war knows no bounds. Almshouse bombed Feb. 10, Newbury, Berks., England.” Naccarata, February 11, 1943. 111-SC-178801.

The logic of the end of the war, fall ’44 onward:

That was when the Allies changed their strategy. They set out to make an Axis surrender irrelevant.

From that winter into the next spring the civilians of Germany and Japan were helpless before a new Allied campaign of systematic aerial bombardment. The air forces and air defense systems of the Axis were in ruins by then. Allied planes flew where they pleased, day or night—500 at a time, then 1,000 at a time, indiscriminately dumping avalanches of bombs on every city and town in Axis territory that had a military installation or a railroad yard or a factory. By the end of the winter most of Germany’s industrial base had been bombed repeatedly in saturation attacks; by the end of the following spring Allied firebombing raids had burned more than 60 percent of Japan’s urban surface area to the ground.

…

This is the dreadful logic that comes to control a lot of wars. (The American Civil War is another example.) The losers prolong their agony as much as possible, because they’re convinced the alternative is worse. Meanwhile the winners, who might earlier have accepted a compromise peace, become so maddened by the refusal of their enemies to stop fighting that they see no reason to settle for anything less than absolute victory. In this sense the later course of World War II was typical: it kept on escalating, no matter what the strategic situation was, and it grew progressively more violent and uncontrollable long after the outcome was a foregone conclusion. The difference was that no other war had ever had such deep reserves of violence to draw upon.

The Vikings would have understood it anyway. They didn’t have a word for the prolongation of war long past any rational goal—they just knew that’s what always happened. It’s the subject of their longest and greatest saga, the Brennu-njalasaga, or The Saga of Njal Burned Alive. The saga describes a trivial feud in backcountry Iceland that keeps escalating for reasons nobody can understand or resolve until it engulfs the whole of northern Europe.

[amazing digression on that]

…But another, even stronger pressure worked against those who understood how hopeless the situation really was: they knew that defeat meant accountability.

“Photograph made from B-17 Flying Fortress of the 8th AAF Bomber Command on 31 Dec. when they attacked the vital CAM ball- bearing plant and the nearby Hispano Suiza aircraft engine repair depot in Paris.” France, 1943. 208-EX-249A-27.

Sandlin’s discussion of the decision to drop the atomic bombs is one of the best I’ve ever read. Here’s how he warms up to it:

We forget now just how pervasive the atmosphere of classified activity was, but there was hardly anybody, in all of the war’s military bureaucracies, who could honestly claim to know everything that was going on. The best information—whole Mississippis of debriefings and intelligence assessments and field reports and rumors—went up the line and vanished. And what returned, from some unimaginable bureaucratic firmament, were orders—taciturn, uncommunicative instructions, raining down ceaselessly, specifying mysterious troop movements, baffling supply requisitions, unexplained production quotas, and senseless rationing goals. Everywhere were odd networks of power and covert channels of communication. No matter how well placed you were, you were still excluded from incessant meetings, streams of memos were routed around your office, old friends grew vague when you asked what department they worked in (a “special” department, they always said—nobody liked coming out and saying “secret”). Everybody was doing something hush-hush; nobody blinked at the most imponderable mysteries.

So there was barely a ripple when, in the spring of 1943, all the leading physicists in America disappeared.

The end of the war, in the US:

That was the message that flashed around the world in the summer of 1945: the war is over, the war is over. Huge cheering crowds greeted the announcement in cities across America and Europe. A spectacular clamor of church bells rang out across the heartland. Wails of car horns and sirens soared up from isolated desert towns, mystifying travelers who’d been on the road all night and hadn’t heard the news. People pounded on doors in hushed apartment buildings, they came out from their houses and laughed and cheered and hugged one another, they swarmed in the streets all through the summer night telling strangers how frightened they’d been and how glad they were it had finally ended. No one could stop talking; every new face that appeared in the crowd was an excuse to ask if they’d heard and then start telling their stories all over again.

“Jubilant American soldier hugs motherly English woman and victory smiles light the faces of happy service men and civilians at Piccadilly Circus, London, celebrating Germany’s unconditional surrender.” Pfc. Melvin Weiss, England, May 7, 1945. 111-SC-205398.

Read the whole thing, is my suggestion.

At the White House, President Truman announces Japan’s surrender. Abbie Rowe, Washington, DC, August 14, 1945. 79-AR-508Q.

I was thinking about this article over Christmas, and resolved that in 2015 I would write Lee Sandlin a note telling him how much it blew my head off. Too late, though. Lee Sandlin died on Dec. 14, 2014 – that’s why, I guess, it was reposted and reached me.

Found that photo on his website, which seems like a great memorial to the man. A list of some of his favorite stuff. And from his section “Rationals:”

I’m just a guy who writes about stuff that happened. But at least there’s a long tradition of this kind of writing. My model has always been William Hazlitt, who two hundred years ago wrote essays, reviews, travel writings, memoirs, celebrity profiles, sports reporting — each piece was simply about what happened, and yet each piece, no matter what the subject, reads like an act of total moral engagement. Hazlitt brought everything he knew, and everything he was, to the task of writing about what happened.

And back beyond that, way back, twenty five hundred years ago, the grandest and airiest work of philosophical speculation ever written begins as a plain report of what happened. In fact, it might easily be mistaken for a review:

Yesterday I went down to the Piraeus with Glaucon the Ariston, to make an offering to the Goddess, and also to see their Festival, which they were putting on for the first time this year. I liked the procession, but I think the procession at Thrace is more beautiful…

Found most of those photos at the National Archives. Here is a ghastly one of a Nazi general who committed suicide, and here are four more amazing ones:

“Dynamic static. The motion of its props causes an `aura’ to form around this F6F on USS YORKTOWN. Rotating with blades, halo moves aft, giving depth and perspective.” November 1943. 80-G-204747A.

“Marines of the 5th Division inch their way up a slope on Red Beach No. 1 toward Surbachi Yama as the smoke of the battle drifts about them.” Dreyfuss, Iwo Jima, February 19, 1945.

“The Yanks mop up on Bougainville. At night the Japs would infiltrate American lines. At Dawn, the doughboys went out and killed them. This photo shows tank going forward, infantrymen following in its cover.” March 1944. 111-SC-189099.

“Dust storm at this War Relocation Authority center where evacuees of Japanese ancestry are spending the duration.” Dorothea Lange, Manzanar, CA, July 3, 1942. 210-G-10C-839.

Tennessee Williams -> Dr. Feelgood -> Mark Shaw

Posted: January 6, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, Florida, Kennedy-Nixon, writing 1 Comment

Tennessee Williams in Key West

Strewn around the apartment of a friend this weekend were a few biographies of Tennessee Williams.

I don’t know much about Tennessee Williams. The most I ever thought about him was when I was briefly in Key West, where there’s some stuff named after him. He jockeys with Hemingway for local literary mascot top honors.