Catching up on New Mexico politics

Posted: January 16, 2019 Filed under: New Mexico Leave a comment

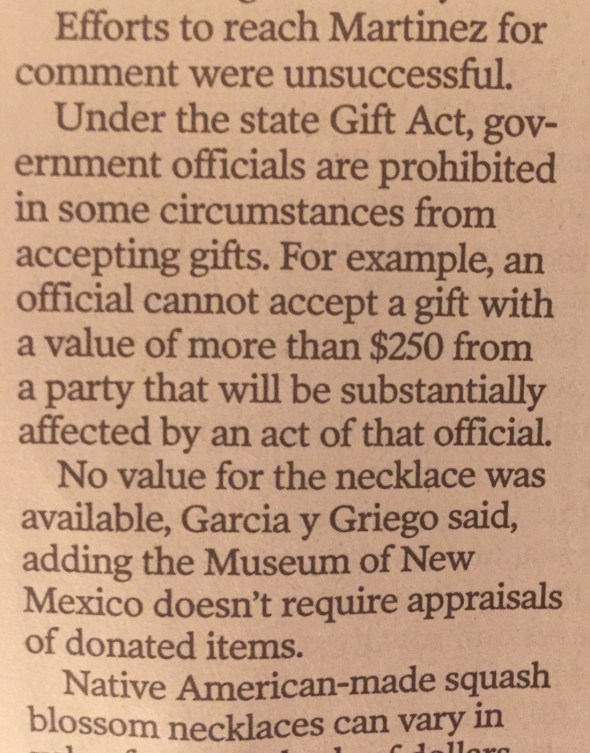

Thom Cole in the Santa Fe New Mexican reports one. Governor Susanna Martinez was given a necklace that ended up at the state museum. Who owns it?

As long as it’s not connected to any act by that official.

A stressful New Year’s Eve:

I made the mistake of looking directly at the sunset in Santa Fe, which is intense. It really did look like the New Mexico state flag:

It’s almost like a powder

Posted: January 14, 2019 Filed under: America Since 1945, moon Leave a comment

It’s sometimes left out of the clips you see, but I like what Neil Armstrong says right before he steps on the moon.

… the surface appears to be very, very fine grained, as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder. Down there, it’s very fine.

JTree

Posted: January 12, 2019 Filed under: America Since 1945, the California Condition Leave a comment

Today’s top story on Hi Desert Star. Photo is captioned:

article by Kurt Schauppner.

What good is bad news in a crisis? I’m more of an evangelist — a good news guy. Hoping reports of damage to trees and such during shutdown is overblown.

Take strength from local heroes?

From the local Facebook page, it sounds like there may be some exaggeration or misunderstanding.

Like so many problems, a few assholes are doing most of the damage. Good people do outnumber assholes, is my experience, and by a wide margin.

obviously don’t chainsaw me, or even shove me too hard, I could be hundreds of years old and I’m very fragile! I’m terrible firewood anyway I’m pretty much made of dust!

Back to good news next post!

Buttered bun

Posted: January 5, 2019 Filed under: sexuality, words Leave a comment

anonymous sends us this one. I may have to investigate the Memoirs of Dolly Morton.

Key Takeaways from the Year of Business

Posted: January 2, 2019 Filed under: business Leave a commentEverybody wants one of a few things in this country. They’re willing to pay to lose weight. They’re willing to pay to grow hair. They’re willing to pay to have sex. And they’re willing to pay to learn how to get rich.

If you buy something because it’s undervalued, then you have to think about selling it when it approaches your calculation of its intrinsic value. That’s hard. But if you buy a few great companies, then you can sit on your ass. That’s a good thing.

– Charlie Munger.

When I was a kid I played this Nintendo game. It was kind of just a bells-and-whistles version of Dopewars.

One significant flaw in the game as a practice tool for the individual investor is it does not account for the effect of capital gains taxes, which would make the rapid fire buying and selling of this game pure madness.

In 2018, my New Year’s Resolution this will be the Year of Business.

Hope and greed vs sound business reasoning

On the speculative side are the individual investors and many mutual funds buying not on the basis of sound business reasoning but on the basis of hope and greed.

So says Mary Buffett and David Clark in Buffetology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett The World’s Most Famous Investor.

By nature I’m a real speculative, hope and greed kinda guy. My mind is speculative, what can I say? Most people’s are, I’d wager. I don’t even really know what “sound business reasoning” means.

The year of business was about teaching myself a new mental model of reasoning and thinking.

Where to begin?

Finally, when young people who “want to help mankind” come to me, asking: “What should I do? I want to reduce poverty, save the world” and similar noble aspirations at the macro-level. My suggestion is:

1) never engage in virtue signaling;

2) never engage in rent seeking;

3) you must start a business. Take risks, start a business.

Yes, take risk, and if you get rich (what is optional) spend your money generously on others. We need people to take (bounded) risks. The entire idea is to move these kids away from the macro, away from abstract universal aims, that social engineering that bring tail risks to society. Doing business will always help; institutions may help but they are equally likely to harm (I am being optimistic; I am certain that except for a few most do end up harming).

so says Taleb in Skin In The Game.

Taleb’s books hit my sweet spot this year, I was entertained and stimulated by them. They raised intriguing ideas not just about probability, prediction and hazard, but also about how to live your life, what is noble and honorable in a world of risk.

Do you agree with the statement “starting a business is a good way to help the world”? It’s a proposition that might divide people along interesting lines. For example, Mitt Romney would probably agree, while Barack Obama I’m guessing would agree only with some qualifications.

I doubt most of my friends, colleagues and family would agree, or at least it’s not the first answer they might come up with. Among younger people, I sense a discomfort with business, an assumption that capitalism is itself kind of bad, somehow.

But could most of those who disagree come up with a clearer answer for how to help mankind?

As an experiment I started thinking about businesses I could start.

My best idea for a business

Selling supplements online seems like a business to start, I remembered Tim Ferriss laying out the steps in Four Hour Work Week, but it wasn’t really calling my name.

My best idea for a business was to buy a 1955 Spartan trailer and set it up by the south side of the 62 Highway heading into Joshua Tree. There’s some vacant land there, and many people arrive there (as I have often myself) needing a break, food, a sandwich, beer, firewood and other essentials for a desert trip.

The point itself – arrival marker of the town of Joshua Tree – is already a point of pilgrimage for many and a natural place to stop, while also being a place to get supplies.

Setting up a small, simple business like that would have reasonable startup cost, aside from my time, and maybe I could employ some people in an economically underdeveloped area.

However, selling sandwiches is not my passion. It’s not why I get out of bed in the morning.

Starting a business is so hard is requires absolute passion. I had a lack of passion.

Further, there was at least one big obstacle I could predict: regulatory hurdles.

Setting up a business that sold food in San Bernadino County would involve forms, permits, regulations.

What’s more, there’d probably be all kinds of rules about what sort of bathrooms I’d need.

This seemed like a time and bureaucracy challenge beyond my capacity.

Work, in other words. I wanted to get rich sitting on my ass, you see, not working.

Plus, I have a small business, supplying stories and jokes, and for most of the Year of Business my business was sub-contracted to HBO (AT&T).

That was more lucrative than selling PB&Js in the Mojave so I suspended this plan pending further review.

Time to pause, since I had to pause anyway.

What can you learn about “business” from books and the Internet?

No way you can learn more from reading than from starting a business, far from it. But in the spare minutes I had that’s what I could do: learn from the business experience of others.

First up,

Excellent. We’ve discussed Munger at length. Most of his interviews and speeches are avail for free online

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.

What are the models? Well, the first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models—because if you just have one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you’ll think it does. You become the equivalent of a chiropractor who, of course, is the great boob in medicine.

It’s like the old saying, “To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.” And of course, that’s the way the chiropractor goes about practicing medicine. But that’s a perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world. So you’ve got to have multiple models.

And the models have to come from multiple disciplines—because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department.

Next:

The Ten Day MBA: A Step By Step Guide To Mastering Skills Taught In America’s Top Business Schools by Steven A. Silbiger.

Fantastic book, it was recommended to me by an MBA grad. Reviewed at length over here, a great cheat sheet and friendly intro to basic concepts of sound business reasoning.

The most important concept it got be thinking about was discounted cash flow analysis. How to calculate the present and future values of money. How much you should pay for a machine that will last eight years and print 60 ten dollar bills a day and cost $20 a day to maintain?

That’s a key question underlying sound business reasoning. How do you value an investment, a purchase, a property, a plant, a factory, or an entire business using sound business reasoning? The prevailing and seemingly best answer is discounted cash flow analysis.

However, the more one learns these concepts, the clearer it becomes that there’s an element of art to all these calculations.

A discounted cash flow analysis depends on assumptions and predictions and estimates that require an element of guessing. Intuition and a feel for things enter into these calculations. They’re not perfect.

A few more things I took away from this book:

- I’d do best in marketing

- Ethics is by far the shortest chapter

- A lot of MBA learning is just knowing code words and signifiers, how to throw around terms like EBITDA, that don’t actually make you wiser and smarter. Consider that George W. Bush and Steve Bannon are both graduates of Harvard Business School.

- To really understand business, you have to understand the language of accounting.

Accounting is an ancient science and a difficult one. You must be rigorous and ethical. Many a business catastrophe could’ve been prevented by more careful or ethical accounting. Accounting is almost sacred, I can see why DFW became obsessed with it.

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations by MacArthur winner Jacob Soll was full of interesting stuff about the early days of double entry accounting. The image of a dreary Florentine looking forward to his kale and bread soup stood out. There are somewhat dark implications for the American nation-state, I fear, if we take the conclusions of this book — that financial accountability keeps nations alive.

However I got very busy at the time I picked up this book and lost my way with it.

Perhaps a more practical focus could draw my attention?

Warren Buffett and the Interpretation of Financial Statements: The Search for the Company with a Durable Competitive Advantage by Mary Buffett and David Clark was real good, and way over my level, which is how I like them.

The key concept here is how to find, by scouring the balance sheets, income statements, and so on, which public companies have to tell you and are available for free, which companies have a durable competitive advantage.

The Little Book That Builds Wealth: The Knockout Formula for Finding Great Investments by Pat Dorsey

and

The Most Important Thing: Uncommon Sense For The Thoughtful Investor by Howard Marks.

are the two that my friend Anonymous Investor recommended, and they pick up the durable competitive advantage idea. Both books have a central understanding the fact that capitalism is brutal competition, don’t think otherwise. To prosper, you need a “moat,” a barrier competitors can’t cross. A patent, a powerful brand, a known degree of quality people will pay more for, some kind of regulatory capture, a monopoly or at least and part of an oligarchy, these can be moats.

What we’re talking about now is not starting a business, but buying into a business.

Buying Businesses

There are about 4,000 publicly traded companies on the major exchanges in the US, and another 15,000 you can buy shares of OTC (over the counter, basically by calling up a broker). You can buy into any of these businesses.

Charlie and I hope that you do not think of yourself as merely owning a piece of paper whose price wiggles around daily and that is a candidate for sale when some economic or political event makes you nervous. We hope you instead visualize yourself as a part owner of a business that you expect to stay with indefinitely, much as you might if you owned a farm or apartment house in partnership with members of your family.

so says Buffett. Oft repeated by him in many forms, I find it here on a post called “Buy The Business Not The Stock.”

But how do you determine what price to pay for a share of a business?

Aswath Damodaran has a website with a lot of great information. Mostly it convinced me that deep valuation is not for me.

Extremely Basic Valuation

Always remember that investing is simply price calculations. Your job is to calculate accurate prices for a bevy of assets. When the prices you’ve calculated are sufficiently far from market prices, you take action. There is no “good stock” or “bad stock” or “good company”. There’s just delta from your price and their price. Read this over and over again if you have to and never forget it. Your job is to calculate the price of things and then buy those things for the best price you can. Your calculations should model the real world as thoroughly as possible and be conservative in nature.

Martin Shkreli on his blog (from prison), 8/1/18

The simplest way to determine whether the price of a company is worth it might be to divide the price of a share of a company by the company’s earnings, P/E.

Today, on December 29, 2018:

Apple’s P/E is 13.16.

Google’s (GOOGL): 39.42.

Netflix (NFLX): 91.43.

Union Pacific Railroad (UNP): 8.99.

This suggests UNP is the cheapest of these companies (you get the most earnings per share) while NFLX is the most “expensive” – you get the least earnings).

But: we’re also betting on or estimating future earnings. These numbers change as companies report their earnings, and the stock price goes up and down. Two variables that are often connected and often not connected.

Now you are making predictions.

The most intriguing and enormous field in the world on which to play predictions is the stock market.

What is the stock market?

The stock market is a set of predictions.

Buying into businesses on the stock market can be a form of gambling. Or, if you use sound business reasoning, it can be investing.

What is investing?

Investing is often described as the process of laying out money now in the expectation of receiving more money in the future. At Berkshire we take a more demanding approach, defining investing as the transfer to others of purchasing power now with the reasoned expectation of receiving more purchasing power – after taxes have been paid on nominal gains – in the future.

More succinctly, investing is forgoing consumption now in order to have the ability to consume more at a later date.

Warren B., in Berkshire’s 2011 Letter To Shareholders.

A great thing about investing is you can learn all about it for the price of an Internet connection. All of Buffett’s letters are free.

How to assess a public company as an investment with sound business reasoning

In researching a specific company, Buffett gathers these resources:

- most recent 10-Ks and 10-Qs

- The annual reports

- News and financial information from many sources

The authors said he wants to see the most recent news stories and at least a decade’s worth of financial data. This allows him to build up a picture of

-

The companies historical annual return on capital and equity

-

Earnings

-

Debt load

-

Share repurchases

-

Management’s record in allocating capital

(from The New Buffetology, Mary Buffett and David Clark).

Cheap stocks (using simple ratios like price-to-book or price-to-sales) tend to outperform expensive stocks. But they also tend to be “worse” companies – companies with less exciting prospects and more problems. Portfolio managers who own the expensive subset of stocks can be perceived as prudent while those who own the cheap ones seem rash. Nope, the data say otherwise.

(from “Pulling The Goalie: Hockey and Investment Implications” by Clifford Asness and Aaron Brown.

This sounds too hard

Correct. Most people shouldn’t bother. You should just buy a low cost index fund that tracks “the market.”

What can we we expect “the stock market” to return?

The VTSAX, the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index, has had an average annual return of 7.01% since inception in 1992. (Source)

10% is the average, says Nerd Wallet.

9.8% is the average annual return of the S&P 500, says Investopedia.

Now, whether the S&P 500 is “the market” is a good question. We’ll return to that.

O’Shaughnessy has thought a lot about the question, it’s pretty much the main thing he’s thought about for the last twenty years or so as far as I can tell, and comes in at around 9%.

Some interesting data from here.

Munger cautions against assuming history repeats itself, in 2005:

(source)

Why Bother Trying To Beat The Market?

A good thing about the Buffettology book is they give you little problems for a specific calculator:

The Texas Instruments BA-35, which it looks like they don’t even really make anymore,. You can get one for $100 over on Amazon.

This calculator is just nifty for working out future values of compounding principal over time.

One concept that must be mashed hard into your head if you’re trying to learn business is the power of compounding.

Let’s say you have $10,000. A good amount of money. How much money can it be in the future?

9% interest, compounded annually, $10,000 principal, 20 years = $61,621

15% interest, compounded annually, $10,000 principal, 20 years= $175,447

9% interest, compounded annually, $1,000 principal, 30 years= $13,731

15% interest, compounded annually, $1,000 principal, 30 years= $86,541

9% interest, $10,000 principal, 40 years= $314,094.2

A significant difference.

Any edge over time adds up.

Let’s say the stock market’s gonna earn 7% over the next years and you have $10,000 to invest. In twenty years you’ll have $38,696.

But if you can get that up to just 8%, you’ll have $46,609.57.

A difference of $8,000.

Is it worth it? Eh, it’s a lotta work to beat the market, maybe not.

Still, you can see why people try it once we’re talking about $1,000,000, and the difference is $80,000, or the edge is 2%, and so on.

Plus there’s something fun just about beating the system.

Lessons from the race track

This book appeals to the same instinct — how to beat the house, what’s the system?

Both Buffett and Munger are interested in race tracks. Here is Munger:

This might be the single most important lesson of the Year of Business. Buffett and Munger repeat it in their speeches and letters. You wait for the right opportunity and you load up.

“The stock market is a no-called-strike game. You don’t have to swing at everything – you can wait for your pitch. The problem when you’re a money manager is that your fans keep yelling, ‘swing, you bum!'”

“Ted Williams described in his book, ‘The Science of Hitting,’ that the most important thing – for a hitter – is to wait for the right pitch. And that’s exactly the philosophy I have about investing – wait for the right pitch, and wait for the right deal. And it will come… It’s the key to investing.”

says Buffett.

“If you find three wonderful businesses in your life, you’ll get very rich. And if you understand them — bad things aren’t going to happen to those three. I mean, that’s the characteristic of it.”

OK but don’t you need money in the first place to make money buying into businesses?

Yes, this is kind of the trick of capitalism. Even Munger acknowledges that the hard part is getting some money in the first place.

“The first $100,000 is a bitch, but you gotta do it. I don’t care what you have to do—if it means walking everywhere and not eating anything that wasn’t purchased with a coupon, find a way to get your hands on $100,000. After that, you can ease off the gas a little bit.”

The Unknown and Unknowable

One of the best papers I read all year was “Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable,” by Richard Zeckhauser.

David Ricardo made a fortune buying bonds from the British government four days in advance of the Battle of Waterloo. He was not a military analyst, and even if he were, he had no basis to compute the odds of Napoleon’s defeat or victory, or hard-to-identify ambiguous outcomes. Thus, he was investing in the unknown and the unknowable. Still, he knew that competition was thin, that the seller was eager, and that his windfall pounds should Napoleon lose would be worth much more than the pounds he’d lose should Napoleon win. Ricardo knew a good bet when he saw it.1

This essay discusses how to identify good investments when the level of uncertainty is well beyond that considered in traditional models of finance.

Zeckhauser, in talking about how we make predictions about the Unknown and Unknowable, gets to an almost Zen level. There’s a suggestion that in making predictions about something truly Unknowable, the amateur might almost have an edge over the professional. This is deep stuff.

“Beating the market”

When we talk about “beating the market,” what’re we talking about?

If you’re talking about outperforming a total stock market index like VTSAX over a long time period, that seems to be a lot of work to pull off something nearly impossible.

Yes, people do it, but it’s so hard to do we, like, know the names of the people who’ve consistently done it.

There’s something cool about Peter Lynch’s idea that the average consumer can have an edge, but even he says you gotta follow that up with a lot of homework.

Lynch, O’Shaughnessy – it’s like a Boston law firm around here. I really enjoyed Jim O’Shaughnessy’s Twitter and his Google talk.

Sometimes when there’s talk of “beating the market,” the S&P 500 is used interchangeably with “the market.” As O’Shaughnessy points out though, the S&P 500 is itself a strategy. Couldn’t there be a better strategy?

is full of backtesting and research, much of it summarized in this article. Small caps, low P/S, is my four word takeaway.

Narrative investing

Jim: Sure. So when I was a teenager, I was fascinated because my parents and some of my uncles were very involved in investing in the stock market, and they used to argue about it all the time. And generally speaking, the argument went, which CEO did they feel was better, or which company had better prospects. And I kind of felt that that wasn’t the right question, or questions to ask. I felt it was far more useful, or, I believed at the time that it would be far more useful to look at the underlying numbers and valuations of companies that you were considering buying, and find if there was a way to sort of systematically identify companies that would go on to do well, and identify those that would go on to do poorly. And so I did a lot of research, and ultimately came up…

says O’Shaughnessy in an interview with GuruFocus. I’m not sure I agree.

Narrative can be a powerful tool in business. If you can see where a story is going, there could be an edge.

would you bet on this woman’s business?

I like assessing companies based on a Google image search of the CEO, for instance.

O’Shaughnessy suggests cutting all that out, getting down to just the numbers. But do you want to invest in, I dunno, RCI Hospitality Holdings ($RICK) (a company that runs a bunch of Hooters-type places called Bombshells) or PetMed Express ($PETS) just because they’re small caps with low p/s ratios and other solid indicators?

Actually those both might be great investments.

I will concede that narrative investing is not systematic. I will continue to ruminate on it.

GuruFocus

Charlie Tian’s book is dense but I found it a great compression of a lot of investing principles. It’s also just like a cool immigrant story.

The service that Charlie Tian built, GuruFocus, is a fantastic resource.

Premium membership costs $449 for a year, which is a lot, but I’d say I got way more than that in value and education from it.

J. R. Collins

His book is great, his Google talk is great.

Templeton

Investing doesn’t have to be all Munger and Buffett. Towards the end of the Year of Business I got into Sir John Templeton.

His thing was finding the point of maximum pessimism. Australian real estate is down? South American mining companies are getting crushed? Look for an opportunity there.

This guy worked above a grocery store in the Bahamas.

Great-niece Lauren carrying on the legacy.

Thought this was a cool chart from her talk demonstrating irrational Mr. Market at work even while long term trends may be “rational.”

Why bother, again?

At some point if you study this stuff it’s like, if you’re not indexing, shouldn’t you just buy Berkshire and have Buffett handle your money for you? You can have the greatest investor who ever lived making money for you just as easily as buying any other stock.

It seems to me that there are 3 qualities of great investors that are rarely discussed:

1. They have a strong memory;

2. They are extremely numerate;

3. They have what Warren calls a “money mind,” an instinctive commercial sense.

Alice Schroeder, his biographer, talking about Warren Buffett. I don’t have any of these.

Even Munger says all his family’s money is in Costco, Berkshire, Li Lu’s (private) fund and that’s it.

In the United States, a person or institution with almost all wealth invested, long term, in just three fine domestic corporations is securely rich. And why should such an owner care if at any time most other investors are faring somewhat better or worse. And particularly so when he rationally believes, like Berkshire, that his long-term results will be superior by reason of his lower costs, required emphasis on long-term effects, and concentration in his most preferred choices.

I go even further. I think it can be a rational choice, in some situations, for a family or a foundation to remain 90% concentrated in one equity. Indeed, I hope the Mungers follow roughly this course.

The answer is it’s fun and stimulates the mind.

A thing to remember about Buffett:

More than 2,000 books are dedicated to how Warren Buffett built his fortune. Many of them are wonderful.

But few pay enough attention to the simplest fact: Buffett’s fortune isn’t due to just being a good investor, but being a good investor since he was literally a child.

The writings of Morgan Housel are incredible.

You can read about Buffett all day, and it’s fun because Buffett is an amazing writer and storyteller and character as well as businessman. But studying geniuses isn’t necessarily that helpful for the average apprentice. Again, it’s like studying LeBron to learn how to dribble and hit a layup.

Can Capitalism Survive Itself?

The title of this book is vaguely embarrassing imo but Yvon Chouinard is a hero and his book is fantastic. Starting with blacksmithing rock climbing pitons he built Patagonia.

They make salmon now?

Towards the end of his book Chouinard wonders whether our economy, which depends on growth, is sustainable. He suggests it might destroy us all, which he doesn’t seem all that upset about (he mentions Zen a lot).

The last liberal art

Have yet to finish this book but I love the premise. Investing combines so many disciplines and models, that’s what makes it such a rich subject. So far I’m interested in Hagstrom’s connections to physics. Stocks are subject to some kind of law of gravity. Netflix will not have a P/E of 95 for forever.

Compare perception to results:

Dominos, Amazon, Berkshire, and VTSAX since 2005.

Stocks Let’s Talk

The stock market is interesting and absurd. The stock market is not “business,” but it’s made of business, you know?

The truth is the most I’ve learned about business has come from conversation.

To continue the conversation, I started a podcast, Stocks Let’s Talk. You can find all six episodes here, each with an interesting guest bringing intriguing perspective.

I intend to continue it and would appreciate it if you rate us on iTunes.

Key Takeaways:

- you can get rich sitting on your ass

- business is hard and brutal and competitive

- you need a durable competitive advantage

- if you are unethical it will catch up to you

- we’re gonna need to get sustainable

- the works of Tian, Lynch, O’Shaughnessy, Templeton, Chouinard, and Munger are worth study

- accounting is crucial and must be done right, even then you can be fooled

- I’m too whimsical for business really but it’s good to learn different models

Whose special praise it is

Posted: December 31, 2018 Filed under: religion Leave a comment

Source: David Sowell for Wikipedia

In this church in Staunton Harold, England, there’s an inscription:

When all things sacred were throughout ye nation Either demollisht or profaned

Sir Robert Shirley Barronet founded this Church whose singular praise it is to have done ye best things in ye worst times And hoped them in the most callamitous.

This is Sir Robert the 4th Baronet, who died a prisoner in the Tower of London.

shoutout to FWJ who told me that one.

Source: Colin Smith for Wikipedia

Hollywood: The Dream Factory

Posted: December 30, 2018 Filed under: the California Condition Leave a comment

Seen on the Paramount lot.

Adobe Walls

Posted: December 30, 2018 Filed under: Texas Leave a comment

Best as I can tell both the first and second Battles of Adobe Walls happened somewhere around here, near what’s now Stinnett, Texas, founded 1926 by A. P. Ace Borger.

That’s from

which I’m finding fantastic. I’m not THAT into The Searchers the movie (I mean I think it’s cool) but this book is amazing as Texas history. I’d put it on a shelf with God Save Texas by Lawrence Wright. They can split the Helytimes J. Frank Dobie Texas History Prize for 2018.

photographer unknown.

A Kiowa ledger drawing possibly depicting the Buffalo Wallow Battle in 1874, one of several clashes between Southern Plains Indians and the U.S. Army during the Red River War.

Billy Dixon was there:

Billy Dixon during his days as an Indian scout. Only known picture of him while he still wore his hair long as he did during his Indian fights.

By August a troop of cavalry made it to Adobe Walls, under Lt. Frank D. Baldwin, with Masterson and Dixon as scouts, where a dozen men were still holed up.[1]:247 “Some mischievous fellow had stuck an Indian’s skull on each post of the corral gate.”[1]:248 The killing had not ended, however; one civilian was lanced by Indians while looking for wild plums along the Canadian River.

This wasn’t that long ago.

Maybe some day I’ll get to that part of Texas. Long Texas drives have formed an important part of my life. Wouldn’t have it any other way.

The Evolution of Pace In Popular Movies

Posted: December 29, 2018 Filed under: film, movies, screenwriting, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Abstract

Movies have changed dramatically over the last 100 years. Several of these changes in popular English-language filmmaking practice are reflected in patterns of film style as distributed over the length of movies. In particular, arrangements of shot durations, motion, and luminance have altered and come to reflect aspects of the narrative form. Narrative form, on the other hand, appears to have been relatively unchanged over that time and is often characterized as having four more or less equal duration parts, sometimes called acts – setup, complication, development, and climax. The altered patterns in film style found here affect a movie’s pace: increasing shot durations and decreasing motion in the setup, darkening across the complication and development followed by brightening across the climax, decreasing shot durations and increasing motion during the first part of the climax followed by increasing shot durations and decreasing motion at the end of the climax. Decreasing shot durations mean more cuts; more cuts mean potentially more saccades that drive attention; more motion also captures attention; and brighter and darker images are associated with positive and negative emotions. Coupled with narrative form, all of these may serve to increase the engagement of the movie viewer.

Keywords: Attention, Emotion, Evolution, Film style, Movies, Narrative, Pace, Popular culture

Over at Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, James E. Cutting has an interesting paper about how popular movies have changed over time in terms of shot duration, motion, luminance, and cuts.

One thing that hasn’t really changed though: a three or four act structure.

In many cases, and particularly in movies, story form can be shown to have three or four parts, often called acts (Bordwell, 2006; Field, 2005; Thompson, 1999). The term act is borrowed from theater, but it does not imply a break in the action. Instead, it is a convenient unit whose size is between the whole film and the scene in which certain story functions occur. Because there is not much difference between the three- and four-act conceptions except that the latter has the former’s middle act broken in half (which many three-act theorists acknowledge; Field, 2005), I will focus on the four-act version.

The first act is the setup, and this is the portion of the story where listeners, readers, or viewers are introduced to the protagonist and other main characters, to their goals, and to the setting in which the story will take place. The second act is the complication, where the protagonists’ original plans and goals are derailed and need to be reworked, often with the help or hindrance of other characters. The third is the development, where the narrative typically broadens and may divide into different threads led by different characters. Finally, there is the climax, where the protagonist confronts obstacles to achieve the new goal, or the old goal by a different route. Two other small regions are optional bookend-like structures and are nested within the last and the first acts. At the end of the climax, there is often an epilogue, where the diegetic (movie world) order is restored and loose ends from subplots are resolved. In addition, I have suggested that at the beginning of the setup there is often a prologue devoted to a more superficial introduction of the setting and the protagonist but before her goals are introduced (Cutting, 2016).

Interesting way to think about film structure. Why are movies told like this?

Perhaps most convincing in this domain is the work by Labov and Waletzky (1967), who showed that spontaneous life stories elicited from inner-city individuals without formal education tend to have four parts: an orientation section (where the setting and the protagonist are introduced), a complication section (where an inciting incident launches the beginning of the action), an evaluation section (which is generally focused on a result), and a resolution (where an outcome resolves the complication). The resolution is sometimes followed by a coda, much like the epilogue in Thompson’s analysis. In sum, although I wouldn’t claim that four-part narratives are universal to all story genres, they are certainly widespread and long-standing

Cutting goes on:

That form entails at least three, but usually four, acts of roughly equal length. Why equal length? The reason is unclear, but Bordwell (2008, p. 104) suggested this might be a carryover from the development of feature films with four reels. Early projectionists had to rewind each reel before showing the next. Perhaps filmmakers quickly learned that, to keep audiences engaged, they had to organize plot structure so that last-seen events on one reel were sufficiently engrossing to sustain interest until the next reel began.

David Bordwell:

source: Wasily on Wiki

I love reading stuff like this, in the hopes of improving my craft at storytelling, but as Cutting notes:

Filmmaking is a craft. As a craft, its required skills are not easily penetrated in a conscious manner.

In the end you gotta learn by feel. We can feel when a story is right, or when it’s not right. I reckon you can learn more about movie story, and storytelling in general, by telling your story to somebody aloud and noticing when you “lose” them than you can by reading all of Brodwell. Anyone who’s pitched anything can probably remember moments when you knew you had them, or spontaneously edited because you could feel you were losing them.

Still, it’s fun to break apart human cognition and I look forward to more articles from Cognitive Science and am grateful they are free!

Another paper cited in this article is “You’re a good structure, Charlie Brown: the distribution of narrative categories in comic strips” by N Cohn.

Thanks to Larry G. for putting me on to this one.

Promise and glamour

Posted: December 17, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a commentYou’re not gonna get what you were promised.

An angry making idea. Maybe one of the most angry-making ideas possible.

I’ve been wondering if anger about the feeling of a broken promise is a major driver in US politics. We were promised something, and we’re not gonna get it.

But what, exactly?

The United States is the absolute best as promising. All of our greatest politicians were great promisers. Our founding fathers were great promisers.

John Lanchester, writing in LRB:

Napoleon said something interesting: that to understand a person, you must understand what the world looked like when he was twenty. I think there’s a lot in that.

[…]

I notice, talking to younger people, people who hit that Napoleonic moment of turning twenty since the crisis, that the idea of capitalism being thought of as morally superior elicits something between an eye roll and a hollow laugh. Their view of capitalism has been formed by austerity, increasing inequality, the impunity and imperviousness of finance and big technology companies, and the widespread spectacle of increasing corporate profits and a rocketing stock market combined with declining real pay and a huge growth in the new phenomenon of in-work poverty. That last is very important. For decades, the basic promise was that if you didn’t work the state would support you, but you would be poor. If you worked, you wouldn’t be. That’s no longer true: most people on benefits are in work too, it’s just that the work doesn’t pay enough to live on. That’s a fundamental breach of what used to be the social contract. So is the fact that the living standards of young people are likely not to be as high as they are for their parents. That idea stings just as much for parents as it does for their children.

But it’s not just politics. If you live in the USA and you turn on your TV, you are being tempted, teased, and promised.

The illusionary promise.

There’s a connection here, I believe, to the world glamour. What is glamour?

Etymology

From Scots glamer, from earlier Scots gramarye (“magic, enchantment, spell”).

The Scottish term may either be from Ancient Greek γραμμάριον (grammárion, “gram”), the weight unit of ingredients used to make magic potions, or an alteration of the English word grammar (“any sort of scholarship, especially occult learning”).

A connection has also been suggested with Old Norse glámr (poet. “moon,” name of a ghost) and glámsýni (“glamour, illusion”, literally “glam-sight”).

A magic spell. An illusion.

Here is Larry McMurtry talking about glamour, and its lack:

Kids in the midwest only get to see even modest levels of glamour if they happen to be on school trips to one or another of the midwestern cities: K.C., Omaha, St. Louis, the Twin Cities. In some, clearly, this lack of glamour festers. Charles Starkweather, in speaking about his motive for killing all those people, had this to say: “I never ate in a high-class restaurant, I never seen the New York Yankees play, I never been to Los Angeles…”

He was teased with something he could never have. Here is Andrew Sullivan on Sarah Palin:

One of the more amazing episodes in Sarah Palin’s early political life, in fact, bears this out. She popped up in the Anchorage Daily News as “a commercial fisherman from Wasilla” on April 3, 1996. Palin had told her husband she was going to Costco but had sneaked into J.C. Penney in Anchorage to see … one Ivana Trump, who, in the wake of her divorce, was touting her branded perfume. “We want to see Ivana,” Palin told the paper, “because we are so desperate in Alaska for any semblance of glamour and culture.”

Interested in readers’ takes on glamour and glimmers.

Flinders Petrie

Posted: December 15, 2018 Filed under: egypt Leave a comment

A photograph Petrie took of his view from the tomb he lived in in Giza 1881

is the caption on that one. We took a look at some of Petrie’s less woke views here.

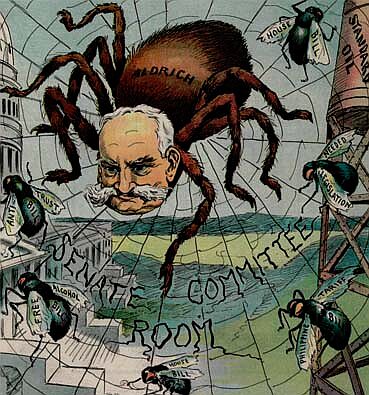

Puck_cartoon_of_Senator_Nelson_Aldrich_1906.jpg

Posted: December 14, 2018 Filed under: rhode island Leave a commentMovie Reviews: The Favourite, Mary Queen of Scots, Schindler’s List

Posted: December 14, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, everyone's a critic, film, movies, the California Condition, Uncategorized Leave a comment

Finding myself with an unexpectedly free afternoon, I went to see The Favourite at the Arclight,

You rarely see elderly people in central Hollywood, but they’re there at the movies at 2pm. While we waited for the movie to start, there was an audible electrical hum. The Arclight person introduced the film, and then one of the audience members shouted out “what’re you gonna do about the grounding hum?”

The use of the phrase “grounding hum” rather than just “that humming sound” seemed to baffle the Arclight worker. Panicked, she said she’d look into it, and if we wanted, we could be “set up with another movie.”

After like one minute I took the option to be set up with another movie because the hum was really annoying. Playing soon was Mary Queen of Scots.

Reminded as I thought about it of John Ford’s quote about Monument Valley. John Ford assembles the crew and says, we’re out here to shoot the most interesting thing in the world: the human face.

Both Saoirse Ronan and Margot Robbie have incredible faces. It’s glorious to see them. The best parts of this movie were closeups.

Next I saw Schindler’s List.

This movie has been re-released, with an intro from Spielberg, about the dangers of racism.

This movie knocked my socks off. I forgot, since the last time I saw it, what this movie accomplished.

When the movie first came out, the context in which people were prepared for it, discussed it, saw it, were shown it in school etc took it beyond the realm of like “a movie” and into some other world of experience and meaning.

I feel like I saw this movie for the first time on VHS tapes from the public library, although I believe we were shown the shower scene at school.

My idea in seeing it this time was to see it as a movie.

How did they make it? How does it work? What’s accomplished on the level of craft? Once we’ve handled the fact that we’re seeing a representation of the Holocaust, how does this work as a movie?

It’s incredible. The craft level accomplishment is on the absolute highest level.

Take away the weight with which this movie first reached us, with what it was attempting. Just approach it as “a filmmaker made this, put this together.”

Long, enormous shots of huge numbers of people, presented in ways that feel real, alive. Liam Neeson’s performance, his mysteries, his charisma, his ambiguity. We don’t actually learn that much about Oscar Schindler. So much is hidden.

Ralph Fiennes performance, the humanity, the realness he brings to someone whose crimes just overload the brain’s ability to process.

The moving parts, the train shots, the wide city shots. Unreal accomplishment of filmmaking.

Some thoughts:

- water, recurring as an image, theme in the movie.

- there are a bunch of scenes of just factory action, people making things with tools and machines. that was the cover. was not the Holocaust an event of the factory age, a twisted branch of Industrial Revolution and efficiency metric spirit?

- reminded that people didn’t know, when it began, “we’re in The Holocaust, this is the Holocaust.” It built. It got worse and worse. there were steps and stages along the way.

- what happened in the the Holocaust happened in a particular time and place in history, focused in an area of central and eastern Europe that had its own, centuries long, context for what you were, who belonged where, history, which tribes go where, what race or nationality meant, how these were understood. Göth’s speech about how the centuries of Jewish history in Kraków will become a rumor. I felt like this movie kind of captured and helped explain some of that, without a ton of extra labor.

- In a way Schindler could almost be seen as like a comic character. He didn’t start his company to save Jews. He starts it to make money from cheap labor. He’s a schemer who sees an opportunity. A rascal out to make a quick buck, a con man and shady dealer who ended up in the worst crime in history, an honest crook who finds he’s in something of vastness and evil beyond his ability to even comprehend.

- There is a scene in this movie that could almost be called funny, or at least comic, when Oscar Schindler (Neeson) tries to explain to Stern (Ben Kingsley) the good qualities of the concentration camp commandant Göth that nobody ever seems to mention!

- Kenneally’s story of how he heard about Schindler:

- The theme of sexuality, Goth’s sexuality, Schindler’s, what it means to love and express your nature versus trying to suppress and kill. Spielberg is not really known for having tough explorations of sexuality in his films but I’d say he took this one pretty square on with a lot bravery?

- if I had a criticism it was maybe that the text on the little intermediary passages that appear on screen a few times and explain the context felt not that clear and kind of unnecessary.

- I feared this movie would have a kind of ’90s whitewash, I felt maybe takes exist, the “actually Schindler’s List is BAD” take is out there, with the idea being that Spielberg put in too much sugar with the medicine which when we talk about the Shoah, unspeakable, unaddressable, is somehow wrong, but damn. I was glad for the sugar myself and I don’t think Spielberg looked away. The Holocaust occurred in a human context, and human contexts, no matter how dark, always have absurdity.

- the scene, for instance, were the Nazis burn in an enormous pyre the months-buried, now exhumed bodies of thousands of people executed during the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto, Spielberg took us as close to the mouth of the abyss as you’re gonna see at a regular movie theater.

What does it mean that Spielberg made a movie about the Holocaust and the two leads are both handsome Nazis?

*As a boy I was attracted to the history of Britain and Ireland as well as Celtic and Anglo-Saxon peoples in America. The peoples of those islands recorded a dramatic history that I felt connected to. They also developed a compelling tradition of telling these history stories with as much drama and excitement as possible eg. Shakespeare.

At a library book sale, I bought, for 50 cents a volume, three biographies from a numbered set from like 1920 of “notable personages,” something like that.

These just looked like the kind of books that a cool gentleman had. Books that indicated status and intelligence.

One of this set that I got was Hernando Cortes. I started that one, but even at that tender age I perceived Cortes was not someone to get behind. The biography had a pro-Cortes slant I found distasteful.

Another volume was about Mary Queen of Scots.

Just on her name, really, I started reading that one.

Mary Queen of Scots’ life was a thrilling story, and this one was melodramatically told. Affairs, murder plots, insults, rumor, execution.

Sometime thereafter, at school, we were all assigned like a book report. To read a biography, any biography, and write a report about it.

Since I’d already read Mary’s biography, I picked her.

As it happened, I overheard my dad confusedly ask my mom why, of all people on Earth, I’d chosen Mary Queen of Scots as the topic for my biography project. My dad did not know the backstory, which my mom patiently explained.

My dad’s reaction on hearing I’d picked Mary Queen of Scots, while not as harsh as Kevin Hart’s imagined reaction on hearing his son had a dollhouse, helps me to understand where Kevin Hart was coming from. Confusion, for starters. Upsetness.

At the time the guys I thought were really heroes were probably like JFK and Hemingway.

George HW Bush

Posted: December 5, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, politics, presidents Leave a commentThought of this photo today.

(what’s David Gergen doing there? sometimes I’ve been that guy).

All posts related to any Bush.

Anybody remember this one?

Posted: December 5, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, music Leave a comment

it’s possible attempts were made to record this song onto an audio cassette.

Best Email Subject Line of the Week

Posted: December 5, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

Sympathy for the Devil

Posted: December 4, 2018 Filed under: religion, writing Leave a commentI was thinking about how a lot of movies and shows (a rewatch of The Sopranos is what made me thing of this) could be called Sympathy For The Devil.

Isn’t the premise of this show to take a murderer and crime boss and get you to sympathize with him?

The Riddle of Chaco Canyon

Posted: December 3, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, desert, native america Leave a comment

Sure, we’ve all heard of Chaco Canyon. It’s one of the 23 UNESCO World Heritage sites in the USA. But I tended to lump it in with Mesa Verde and the other cliff dwellings and move on.

Then an ad in High West (“for people who care about the West”) caught my eye. $25 for a year’s subscription to Archaeology Southwest, PLUS the Chaco archaeology report? Yes!

Once you get going on Chaco Canyon, it’s hard to stop.

Bob Adams at Wikipedia

What was it? Who built it? How? What happened? What were they up to? Why there?

Room 170 at source: this Gamblers House post

One of the most important conclusions that leaps out of this book is that most of the societies examined had attitudes toward nature that were fairly compatible with a responsible, sustainable relationship with the environment, but that nearly all of them ended up destroying their environment anyway, either because they lacked the scientific and technological knowledge to know how to act best or because they let their values change as they became wealthier and more powerful through exploitation of natural resources.

from this post.

Sometimes you start looking for something, more information, help, and you find exactly what you’re looking for. You find a guide who can give you exactly the information you’re looking for, in a digestible way.

That’s what I found when I found The Gambler’s House. A dense, rich blog about Chaco by a former Park Service seasonal guide, he / she seems to know this stuff at a deep level. Here are two of the closest I find to autobiography.

source: Gambler’s House

The author, who signs the name Teofilio, writes with clarity, patience, intelligence, respect for the reader, restrained but confident style, and a steady, calm voice, walking us through questions, debates, and controversies within the scholarship:

So if great houses weren’t pueblos, what were they? Here’s where contemporary archaeologists tend to break into two main camps. One sees them as elite residences, part of some sort of hierarchical system centered on the canyon or, alternatively, of a decentralized system of “peer-polities” with local elites who emulated the central canyon elites in the biggest great houses. In either case, note that the great houses are still presumed to have been primarily residential. The difference from the traditional view is quantitative, rather than qualitative. These researchers see the lack of evidence for residential use in most rooms, but they also see that there is still some evidence for residential use, and they emphasize that and interpret the other rooms as evidence of the power and wealth of the few people who lived in these huge buildings and were able to amass large food surpluses or trade goods (or whatever). The specific models vary, but the core thing about them is that they see the great houses as houses, not for the community as a whole (most people lived in the surrounding “small houses” both inside and outside of the canyon) but for a lucky few.

In this camp are Steve Lekson, Steve Plog, John Kantner, probably Ruth Van Dyke (although she doesn’t talk about the specific functions of great houses much), and others.

On the other side are those who see the difference between pueblos and great houses as qualitative. To these people, the great houses were not primarily residential in function, although they may have housed some people from time to time. Most of these researchers see the primary function of the sites as being “ritual” in some sense, although what that means is not always clearly specified. In many cases a focus on pilgrimage (based on questionable evidence) is posited. This group tends to make a big deal out of the astronomical alignments and large-scale planning evident in the layouts and positions of the great houses within their communities. They tend to see the few residents of the sites as caretakers, priests, or other individuals whose functions allowed them to reside in these buildings. Importantly, they don’t see these sites as equivalent to other residences in any meaningful way. They are instead public architecture, perhaps built by egalitarian communities as an act of religious devotion. Examples of monumental architecture built by such societies are known throughout the world (Stonehenge is a famous example), and this view fits with the traditional interpretation of modern Pueblo ethnography, which sees the Pueblos as peaceful, egalitarian, communal villagers. There is a long tradition of projecting this image back into the prehistoric past based on the obvious continuities in material culture, so while these scholars are in some ways breaking with tradition in not seeing great houses as residential, they are also staying true to tradition in other ways by interpreting them as a past manifestation of cultural tendencies still known in the descendant societies but expressed in different ways.

(from this post).

While many archaeologists have made valiant attempts to fit the rise of Chaco into models based on local and/or regional environmental conditions, they have been generally unsuccessful in finding a model that convincingly explains the astonishing florescence of the Chaco system in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries. This has inspired some other archaeologists more recently to try a different tack involving less environmental determinism and more historical contingency. This seems promising, but finding sufficient evidence for this sort of approach is difficult when it comes to prehistoric societies like Chaco. The various camps of archaeologists will likely continue to argue about the nature of Chaco for a long time, I think. Meanwhile, the mystery remains.

from the post “Plaster“

I doubt this mystery will ever be totally solved. There’s just too much information that is no longer available for various reasons. That’s not necessarily a problem, though. At this point the mysteries of Chaco are among its most noteworthy characteristics. Sometimes not knowing everything, and accepting that lack of knowledge, is useful in coming to terms with something as impressive, even overwhelming, as Chaco. One way to deal with it all is to stop trying to figure out every detail and to just observe. The experience that results from this approach may have nothing to do with the original intent of the builders of the great houses of Chaco, but then again it may have everything to do with that intent. There’s no way to be sure, and there likely never will be. But that’s okay. Sometimes mysteries are better left unsolved.

What of the Gambler legend for the origin of Chaco? Alexandria Witze at Archaeology Conservancy tells us:

Navajo oral histories tell of a Great Gambler who had a profound effect on Chaco Canyon, the Ancestral Puebloan capital located in what is now northwestern New Mexico. His name was Nááhwiilbiihi (“winner of people”) or Noqóilpi (“he who wins men at play”), and he travelled to Chaco from the south. Once there, he began gambling with the locals, engaging in games such as dice and footraces. He always won.

Faced with such a formidable opponent, the people of Chaco lost all their possessions at first. Then they gambled their spouses and children and, finally, themselves, into his debt. With a group of slaves now available to do his bidding, the Gambler ordered them to construct a series of great houses—the monumental architecture that fills Chaco Canyon today.

when I picture The Gambler

What was up with Chaco Canyon’s roads? They were thirty feet wide, perfectly straight, and seem to go… nowhere?

Once you’re into Chaco Canyon before you know it you’re into Hovenweep.

and where does Mesa Verde fit into this?

So what was the relationship between the two? The short answer is that no one knows.

source: rationalobserver for wikipedia

This is a great post with a possible Chaco theory:

Briefly, what I’m proposing is that the rise of Chaco as a regional center could have been due to it being the first place in the Southwest to develop detailed, precise knowledge of the movements of heavenly bodies (especially the sun and moon), which allowed Chacoan religious leaders to develop an elaborate ceremonial calendar with rituals that proved attractive enough to other groups in the region to give the canyon immense religious prestige. This would have drawn many people from the surrounding area to Chaco, either on short-term pilgrimages or permanently, which in turn would have given Chacoan political elites (who may or may not have been the same people as the religious leaders) the economic base to project political and/or military power throughout a large area, and cultural influence even further.

The “sexiest” post title:

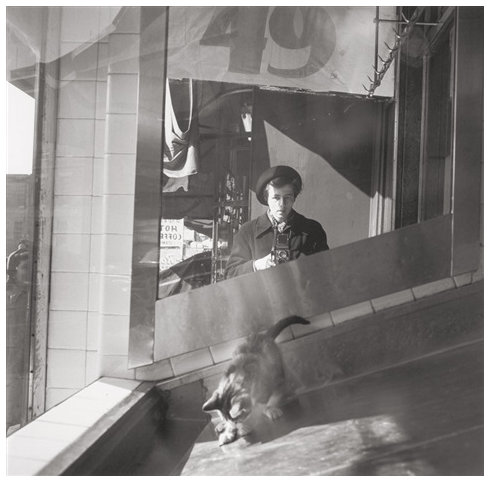

Vivian Maier

Posted: December 2, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history, photography Leave a comment

stole that straight from Artnet.

The tale of who owns Vivian Maier’s work is interesting. Through some twists, John Maloof, the Chicago real estate developer (?) who found and bought most of the physical photos at a storage auction, does not at present own the copyright:

Until those heirs are determined, the Cook County Administrator will continue to serve as the supervisor of the Maier Estate.