Movie idea

Posted: March 13, 2025 Filed under: film Leave a comment

Mikey Madison

is Dolley Madison.

Aaron Burr set her up with James Madison. A haunted photograph of her late in life.

Amazing things happening in the Vertigo Sucks community

Posted: September 3, 2024 Filed under: everyone's a critic, film 1 Comment

The comments coming to life on our 2013 post. To be clear, our problem isn’t so much with Vertigo itself as with film critics who overhype it, hurting rather than helping the cause of old movie appreciation.

First look at Common Side Effects

Posted: July 27, 2024 Filed under: America Since 1945, art, comedy, drugs, film, hely, how to live, pictures, plays, screenwriting, story, the world around us, Wonder Trail Leave a commentFor the past couple of years I’ve been working on this animated show I co-created with the great Joe Bennett. Even adjusting for my personal bias, I believe it came together in an amazing way and will be an incredible show. Coming in 2025.

How Quentin Tarantino got into Hollywood

Posted: July 21, 2021 Filed under: film, movies Leave a commentThought this was interesting, from this Deadline interview with Mike Fleming. Luck + preparation?:

How I eventually got into the industry to some degree was, my friend Scott Spiegel was going to write something for the director, William Lustig, who did Maniac, Maniac Cop. He wanted to bring me in to help him, and Lustig looked at me and said, “Who is this f*cking guy?” And so, he gave them my script for True Romance, just as an audition piece. He read it, and he really, really liked it and couldn’t quite get it out of his head. He had a deal with Cinetel at the time, and so he showed it to the people there and bought it. They were going to make it, with William Lustig. But then the woman who was the head of development at Cinetel, Caitlin Knell — who really helped me out in getting started in my career — she was really good friends with Tony Scott because she used to be his assistant. She knew I was a big fan of his. So she invited me to the set of The Last Boy Scout, and I was able to watch filming for a little bit, and she took me to Tony’s birthday party. I was in heaven. I was only just a year out of the video store. And apparently, I made such a nice impression on Tony that he was like, “Who is this kid?” She said, “The boy’s a really good writer, I’m working with him on this thing at Cinetel.” And he goes, ‘Well, send me a couple of his scripts. Let me read them. He seems like a nice guy. I mean, he really likes me, so he’s obviously got good taste. Send me a couple of his scripts.”

She sent him True Romance and Reservoir Dogs. He read them, and he called Cat in a month and goes, “I want to make it. I want to make Reservoir Dogs. Let’s do it right now.” She was, “Well, OK. That one he won’t give you. That one he looks like he could make himself.” Tony says, “OK, OK, I’ll do the other one.” And then it became a situation where Cinetel was going to make it, but then Tony wanted to make it. I go, “Well, get it away from Cinetel, or pay them off or whatever or make it for them.” He said, “OK,” and that’s how it happened.

The Coen Brothers Interviews

Posted: December 12, 2020 Filed under: advice, film, movies 3 Comments

If you’re out in Hollywood, you probably have a relationship with the movies. Even just at the most basic level, the movie theaters are better here. There are the big movie palaces, Grauman’s Chinese and all that, for special occasions, and The Aero and the Egyptian, but just for everyday moviegoing, I’ll take the Arclight over any place I went to in New York City. There’s now an Arclight in Boston, and a few elsewhere, but man, when I first got to LA I was like OK, here’s how to see a movie.

Of course, you may think you’re pretty into movies, and then you dive in and realize, whoa, some of these people are into movies. I remember hearing a talk by Steve Zalian at some Writers Guild thing where he mentioned he’d seen Serpico ninety times. Doesn’t appear to be online, but there’s a 2014 Playboy interview with David Fincher where he talks about movies he’d seen a hundred times or so. Listen to Brad Pitt and Leo on Maron talk about watching movies with Quentin Tarantino.

You’re liable to be quickly humbled as just a movie fan once you encounter the level of movie fan out here. Some people make their whole identity as film enthusiasts and amateur or semi-pro critics. Not everyone who’s obsessed with movies is a big success at them:

INTERVIEWER

What happens to those girls, those aspiring starlets? Do they sit around in Schwab’s drugstore, or the Brown Derby, or whatever?

SOUTHERN

In the beginning, they come to Hollywood, presumably, with the idea of the action. Then they find out that you can’t even get into any of these buildings without an agent, that there’s no possibility of getting in, that even a lot of the agents can’t get in. Meanwhile a substitute life begins, and they get into the social scene, you know. They’re working as parking attendants, waitresses, doing arbitrary jobs . . .

INTERVIEWER

Hoping that somebody will see them?

SOUTHERN

Finally they forget about that, but they’re still making the scene. They continue to have some vague peripheral identification with films—like they go to a lot of movies, and they talk about movies and about people they’ve seen on the street, and they read the gossip columns and the movie magazines, but you get the feeling it’s without any real aspiration any longer. It’s the sort of vicariousness a polio person might feel for rodeo.

Terry Southern, talking to The Paris Review. Not clear what year that interview was conducted, certainly well before 1995, when Southern died.

I’d been obsessing over the Conversations With Writers series from the University Press of Mississippi. Browsing their website, I saw they had a whole Conversations With Filmmakers series. The website had a spot where you could request a review copy, so I asked for a review copy of The Coen Brothers Interviews, and Courtney at UP of Miss very kindly sent me one.

These books take the form of collections of interviews published elsewhere. There are 28 in this case, including a transcript of a Terry Gross interview, an Onion A.V. Club interview with Nathan Rabin, a Vogue profile (? was Vogue different in 1994) by Tad Friend. The interviews are often keyed to a particular movie out or in production at the time of the piece. This volume came out in 2006, and the last two short pieces, more articles than interviews, are focused on the soon to be released The Ladykillers.

There’s a thoughtful introduction as well by William Rodney Allen, who explores in particular and appropriately enough the connection the brothers have to the Mississippi Delta, as seen in O Brother Where Art Thou. I was surprised to learn from this book that Miller’s Crossing was shot in New Orleans.

“We looked around San Francisco, but you know what that looks like: period but upscale – faux period,” says Ethan. Then someone suggested New Orleans, parts of which surprisingly fit the bill. Outside of the distinctive French Quarter, there were plenty of places that could pass for a generic Anytown in the late 1920s. “New Orleans is sort of a depressed city; it hasn’t been gentrified,” says Ethan. “There’s a lot of architecture that hasn’t been touched, storefront windows that haven’t been replaced in the past sixty years.”

The Coen Brothers don’t seem particularly interested in being interviewed. Don’t take my word for it:

We often resist the efforts of… people who are interviewing us to enlist us in the process ourselves. And we resist it not because we object to it but simply because it ins’t something that particularly interests us.

so says Joel in an interview with Damon Wise of Moving Pictures magazine, which itself isn’t reprinted in this book, but is quoted in a Boston Phoenix piece from 2001 by Gerald Peary which you will find here. True enough, in most of the conversations the Coens seem game enough but not effusive, and the interviewers or profilers often have to do a bit of legwork themselves to find some meat. They ask why Hudsucker Proxy wasn’t more successful (“I dunno, why was Fargo not a flop?” replies Joel. “It’s as much a mystery to me that people went to see Fargo, which was something we did thinking ah, y’know, about three people will end up seeing it, but it’ll be fun for us”). They ask why the brothers are drawn to James M. Cain (“what intrigues us about Cain is that the heroes of his stories are nearly always schlubs – loser guys involved in dreary, banal existences,” says Joel, again).

One aspect of their career I hadn’t realized before I read this book was Joel’s relationship with Sam Raimi, who gave him a job as an assistant editor on Evil Dead.

Raimi had remarked that the Coens have several thematic rules: The innocent must suffer; the guilty must be punished; you must taste blood to be a man… Joel and Ethan shrugged, separately.

Barry Sonnenfeld was their first director of photography, I also hadn’t known that, perhaps common knowledge to true Coenheads.

In terms of moviemaking secrets, how to get them made, without interference and while maintaining a vision, as the Coens so consistently have, this might be the closest we come. Joel once more, talking to Kristine McKenna for Playboy, 2001:

Our movies are inexpensive because we storyboard our films in the the same highly detailed way Hitchcock did. As a result, there’s little improvisation. Preproduction is cheap compared with trying to figure things out on a set with an entire crew standing around.

Amazon has a couple other glitzier books on the Coens. This book is more raw data than polished product. Sometimes the interviews cover similar turf, or bore down on the specifics of some upcoming project. To me, I find you get a great deal from going to the source. Going to the source is a theme of Helytimes. This book is really a sourcebook, and that’s very valuable.

If not the Coens, perhaps another in the Conversations with Filmmakers series. There are 105! Errol Morris? David Lynch? Jane Campion? I’d like to read all of them, if I had but the time!

In my opinion, a book review should 1) give you some summary, basic idea, and nuggets of insight from the book and 2) give you enough info to know whether you should buy it or not.

I hope I’ve done that for you!

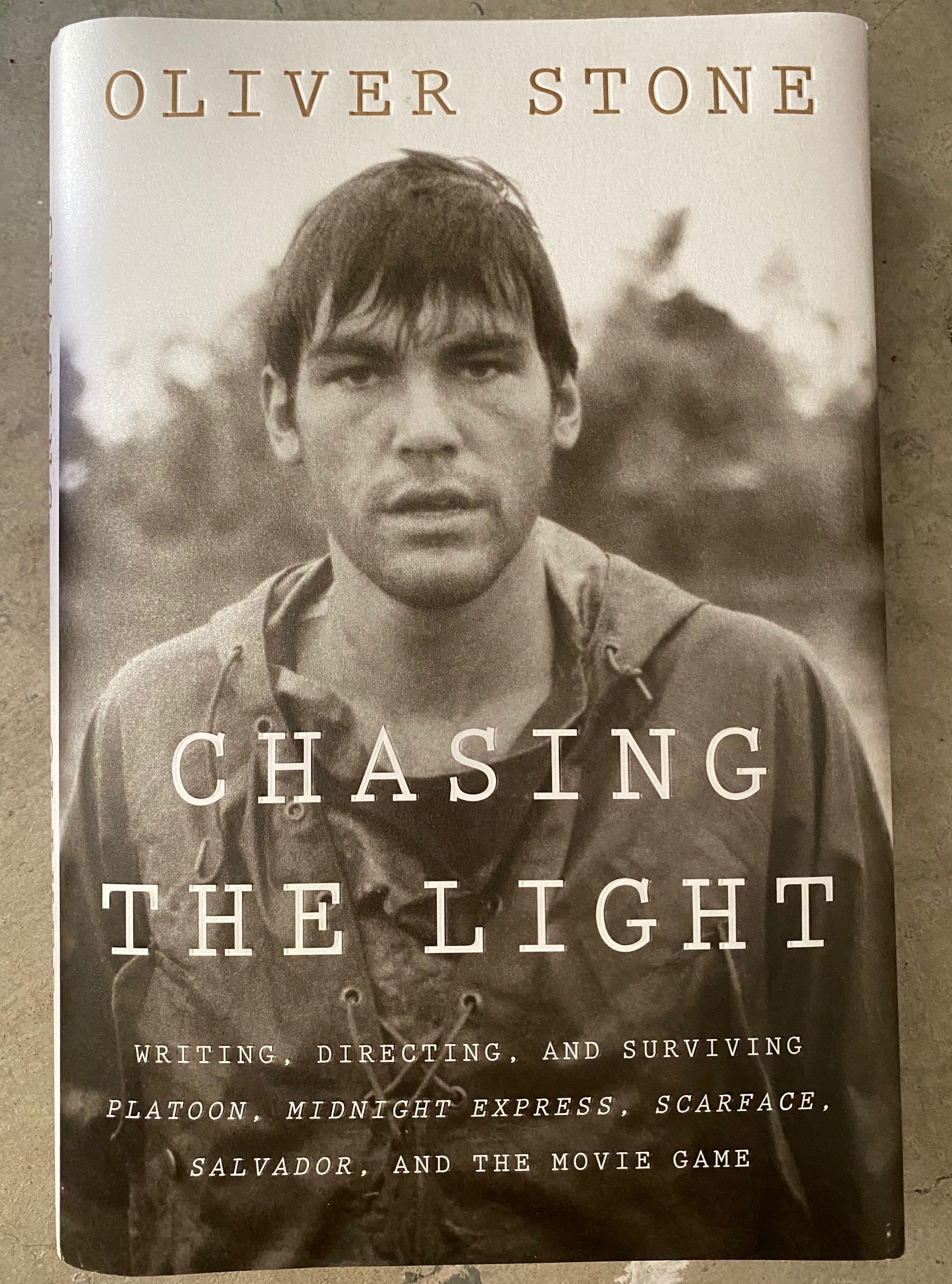

Chasing The Light by Oliver Stone

Posted: August 10, 2020 Filed under: America Since 1945, film, movies Leave a comment 1969. Young Oliver Stone, back from Vietnam, kind of lost in his life, having barely escaped prison time for a drug charge in San Diego, enrolls at NYU’s School of the Arts, undergrad. He makes a short film in 16mm with some 8mm color intercuts, about a young veteran, played by himself, who wanders New York, and throws a bag full of his photographs off the Staten Island ferry, with a voiceover of some lines from Celine’s Journey to the End of Night.

1969. Young Oliver Stone, back from Vietnam, kind of lost in his life, having barely escaped prison time for a drug charge in San Diego, enrolls at NYU’s School of the Arts, undergrad. He makes a short film in 16mm with some 8mm color intercuts, about a young veteran, played by himself, who wanders New York, and throws a bag full of his photographs off the Staten Island ferry, with a voiceover of some lines from Celine’s Journey to the End of Night.

He shows it to his class. The professor is Martin Scorsese.

When the film ended after some eleven taut minutes and the projector was turned off, I steeled myself in the silence for the usual sarcasm consistent with our class’s Chinese Cultural Revolution “auto-critique,” in which no one was spared. What would my classmates say about this?

No one had yet spoken. Words become very important in moments like this. And Scorsese simply jumped all the discussion when he said, “Well – this is a filmmaker.” I’ll never forget that. “Why? Because it’s personal. You feel like the person who’s making it is living it,” he explained. “That’s why you gotta keep it close to you, make it yours.” No one bitched, not even the usual critiques of my weird mix, sound problems, nothing. In a sense, this was my coming out. It was the first affirmation I’d had in… years. This would be my diploma.

This book covers the first forty years of Stone’s life, with much of it centered on the making of Salvador, Platoon, and Scarface, after experiences in Vietnam and jail.

The movies of Stone’s later career – The Doors, JFK, W, Nixon – are the ones that mean the most to me, and those aren’t covered in this book. But I was still pretty compelled by it, surprised by the sensitive, easily wounded young man who emerges, experienced in violence but capable of great tenderness. Struggling with his father’s expectations, his socialite mother. His fast rise in Hollywood, frustrations and joys, and the druggy swirl that almost undoes it all, like when he gave a rambling Golden Globe acceptance speech after “a few hits of coke, a quaalude or two, several glasses of wine.” (Video of the speech since scrubbed from YouTube, unfortch).

How about Peter Guber pitching what became Midnight Express:

Make a little money for college. Innocent kid basically, knows nothing, first trip outside the country right? They beat the shit out of him! Everything in the world happens to him – and then he escapes from this island prison on a rowboat…. that’s right! A rowboat, believe it or not. Gets back to the mainland, then runs through a minefield across the Turkish border into Greece – right? Unbelievable! Great story! Tension – like you wrote Platoon. Every single second, you want to feel that tension!

Tigertail (2020)

Posted: April 10, 2020 Filed under: film, movies 1 Comment

If you are a Helytimes reader who hasn’t heard about Tigertail, Alan Yang’s directorial debut, which is NOW on Netflix, Heaven help you. Very proud of my former roomie on this tremendous achievement, will be watching tonight.

Cats (2019)

Posted: December 24, 2019 Filed under: film 1 Comment

A tribe of cats must decide yearly which one will ascend to the Heaviside Layer and come back to a new life

Somebody who saw the movie before me said “it helps if you know that the Cats are competing in a contest of singing about their lives to see who gets to go up in a hot air balloon and die and then get reborn with a new life.” That does help.

A critical failure can be kind of fun, even a badge of honor, but a colossal financial failure is bad. That makes everyone uncomfortable.

I kind of enjoyed my experience of the movie, I wasn’t bored. Several people in my theater (at The Grove) were straight up bawling crying with real emotion, both during “Memory” and during the song Dame Judi Dench sings about growing old (“Finale: The Ad-Dressing of Cats”). I myself was quite moved. I’d never seen Cats the musical and didn’t know much about it. I was struck that this was really kind of a veiled story about city lowlifes and pimps and shady customers and dramatic sad sacks, and theater kids. It’s about finding redemption for a squandered or spent life? The setting appeared to be something like London’s West End and Trafalgar Square.

It’s almost silly to talk about what went wrong with this movie. When Idris Elba is dancing and his genitals are either tucked into a suit or disguised with some kind of CGI, so he doesn’t even have normal cat genitals, that’s a jarring image, certainly, and takes one out of the film.

Francesca Hayward, the Kenyan-born dancer who plays White Cat, the star or at least our guide through this thing, is an amazingly gifted dancer and performer. Probably. It sounds like it, I can’t really say, because this movie hits at level of fakiness where I can’t really tell what’s her, and what’s faked. I can see how that might sound “cool” in conception but in reality it just robs me of seeing human talent.

Why didn’t they just assemble this amazing cast of talented actors for about thirty days and then have them put on a simple production of Cats in a big empty warehouse? It would’ve been much more engaging to see what these performers can really do, to see what they might bring out in each other, to see what kind of magic they can make just with their bodies and voices. I suspect the answer to why they didn’t do that is:

1) they didn’t trust an audience would consider that spectacular, new, unique enough for a movie

and

2) it would’ve been too hard.

The makers of this movie didn’t trust an audience, they assumed we could be easily fooled by manipulated computer-designed imagery that’s not “cheap” in terms of money but is cheap in terms of artistry. That, to me, explains some of the reaction this movie. These people think we’re fools. Whoever (and I guess we have to say “director Tom Hooper”) made this movie didn’t go forward to make something they themselves would find really cool and impressive and special, just the way they’d like to see the story told, and then struggle to achieve that vision, and then share it with us. Instead, the makers set out to fake us out with tricks that we know are tricks, and they know are tricks. It’s disrespectful, and that’s shameful.

How great would it have been to actually stage Cats with Taylor Swift and Jennifer Hudson and James Corden and Ian McKellan and Dame Judi Dench, stripped down if necessary, and just show us the results? But that’s too hard, they never could’ve convinced those actors, they never could’ve gotten the scheduling right, to do that would’ve been an act of absurd daring and ambition. So instead they just threw money at it and made something cheap and gaudy and unconvincing. The result is kind of like being a kid and being taken to Disneyland and your divorced dad is buying everything but he’s on his phone the whole time. You know you aren’t being given anything of real value.

Money is cheap in movies. It’s not impressive. Making an expensive movie is easy, Hollywood does it all the time. Talent and vision and effort and energy and collaboration are what’s rare. That’s what’s impressive. Some of that actually shines through the movie of Cats, despite everything.

I thought James Corden did a heroic job, a true showman. And Laurie Davidson as Mir. Mistoffelees was great.

I compared a few of the songs to the Broadway versions and preferred the movie versions. (Compare, for instance, Corden’s Bustopher Jones).

No, the reason why people will hunger to see ”Cats” is far more simple and primal than that: it’s a musical that transports the audience into a complete fantasy world that could only exist in the theater and yet, these days, only rarely does.

That’s what Frank Rich said back in 1982. These days movie audiences are REGULARLY transported to complete fantasy worlds that could only exist in the movies. Why mess around with trying to translate a magical theater experience to that? (Deadline highlights the obvious reasons: good track record of musicals for Universal, incredible cast, huge hit IP, etc).

Maybe that was the mistake of the movie, to try and duplicate the massive transformation the show did to a theater to something a movie could do. To do that, while also showing you the faces of these beloved actors, was maybe just a mismatch?

And also the plot is very strange. It’s funny, almost one of the lessons of Cats the Broadway sensation is that people can go along with a pretty dense internal logic without a lot of handholding provided there’s a lot of intense longing, empathy, nostalgia, vivid expressions of where characters are coming from. However many million people who enjoyed Cats the show just accepted the many uses of the word “jellicle” and went along. People will do that, if the vision is coherent! Fairy tales are full of that kind of buy-in. Maybe the filmmaking team just lost their confidence somewhere along the way. I’m made to understand they actually added more of a plot, for the movie.

The Financial Times liked the film! I give it a B+. I’m not here to poo on things, it was a fun early afternoon.

Reader Dan G comments:

To me it seems likely “they” made the choices they made in good faith, with high hopes and something just didn’t quite work. Happens all the time.

I agree!

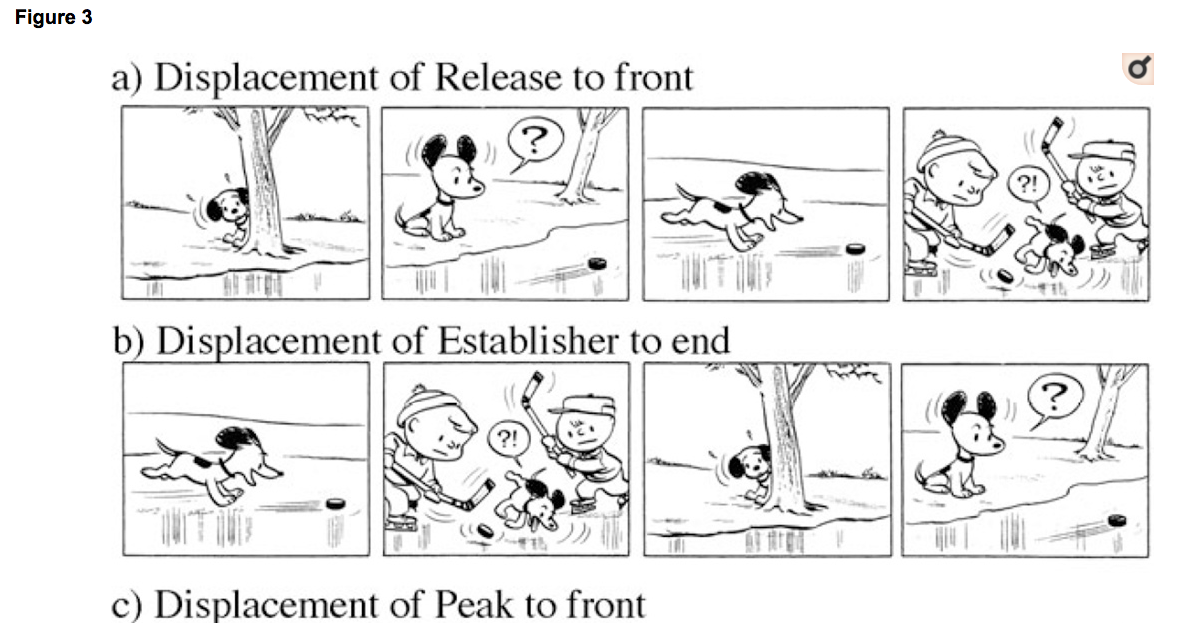

The Evolution of Pace In Popular Movies

Posted: December 29, 2018 Filed under: film, movies, screenwriting, writing, writing advice from other people Leave a comment

Abstract

Movies have changed dramatically over the last 100 years. Several of these changes in popular English-language filmmaking practice are reflected in patterns of film style as distributed over the length of movies. In particular, arrangements of shot durations, motion, and luminance have altered and come to reflect aspects of the narrative form. Narrative form, on the other hand, appears to have been relatively unchanged over that time and is often characterized as having four more or less equal duration parts, sometimes called acts – setup, complication, development, and climax. The altered patterns in film style found here affect a movie’s pace: increasing shot durations and decreasing motion in the setup, darkening across the complication and development followed by brightening across the climax, decreasing shot durations and increasing motion during the first part of the climax followed by increasing shot durations and decreasing motion at the end of the climax. Decreasing shot durations mean more cuts; more cuts mean potentially more saccades that drive attention; more motion also captures attention; and brighter and darker images are associated with positive and negative emotions. Coupled with narrative form, all of these may serve to increase the engagement of the movie viewer.

Keywords: Attention, Emotion, Evolution, Film style, Movies, Narrative, Pace, Popular culture

Over at Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, James E. Cutting has an interesting paper about how popular movies have changed over time in terms of shot duration, motion, luminance, and cuts.

One thing that hasn’t really changed though: a three or four act structure.

In many cases, and particularly in movies, story form can be shown to have three or four parts, often called acts (Bordwell, 2006; Field, 2005; Thompson, 1999). The term act is borrowed from theater, but it does not imply a break in the action. Instead, it is a convenient unit whose size is between the whole film and the scene in which certain story functions occur. Because there is not much difference between the three- and four-act conceptions except that the latter has the former’s middle act broken in half (which many three-act theorists acknowledge; Field, 2005), I will focus on the four-act version.

The first act is the setup, and this is the portion of the story where listeners, readers, or viewers are introduced to the protagonist and other main characters, to their goals, and to the setting in which the story will take place. The second act is the complication, where the protagonists’ original plans and goals are derailed and need to be reworked, often with the help or hindrance of other characters. The third is the development, where the narrative typically broadens and may divide into different threads led by different characters. Finally, there is the climax, where the protagonist confronts obstacles to achieve the new goal, or the old goal by a different route. Two other small regions are optional bookend-like structures and are nested within the last and the first acts. At the end of the climax, there is often an epilogue, where the diegetic (movie world) order is restored and loose ends from subplots are resolved. In addition, I have suggested that at the beginning of the setup there is often a prologue devoted to a more superficial introduction of the setting and the protagonist but before her goals are introduced (Cutting, 2016).

Interesting way to think about film structure. Why are movies told like this?

Perhaps most convincing in this domain is the work by Labov and Waletzky (1967), who showed that spontaneous life stories elicited from inner-city individuals without formal education tend to have four parts: an orientation section (where the setting and the protagonist are introduced), a complication section (where an inciting incident launches the beginning of the action), an evaluation section (which is generally focused on a result), and a resolution (where an outcome resolves the complication). The resolution is sometimes followed by a coda, much like the epilogue in Thompson’s analysis. In sum, although I wouldn’t claim that four-part narratives are universal to all story genres, they are certainly widespread and long-standing

Cutting goes on:

That form entails at least three, but usually four, acts of roughly equal length. Why equal length? The reason is unclear, but Bordwell (2008, p. 104) suggested this might be a carryover from the development of feature films with four reels. Early projectionists had to rewind each reel before showing the next. Perhaps filmmakers quickly learned that, to keep audiences engaged, they had to organize plot structure so that last-seen events on one reel were sufficiently engrossing to sustain interest until the next reel began.

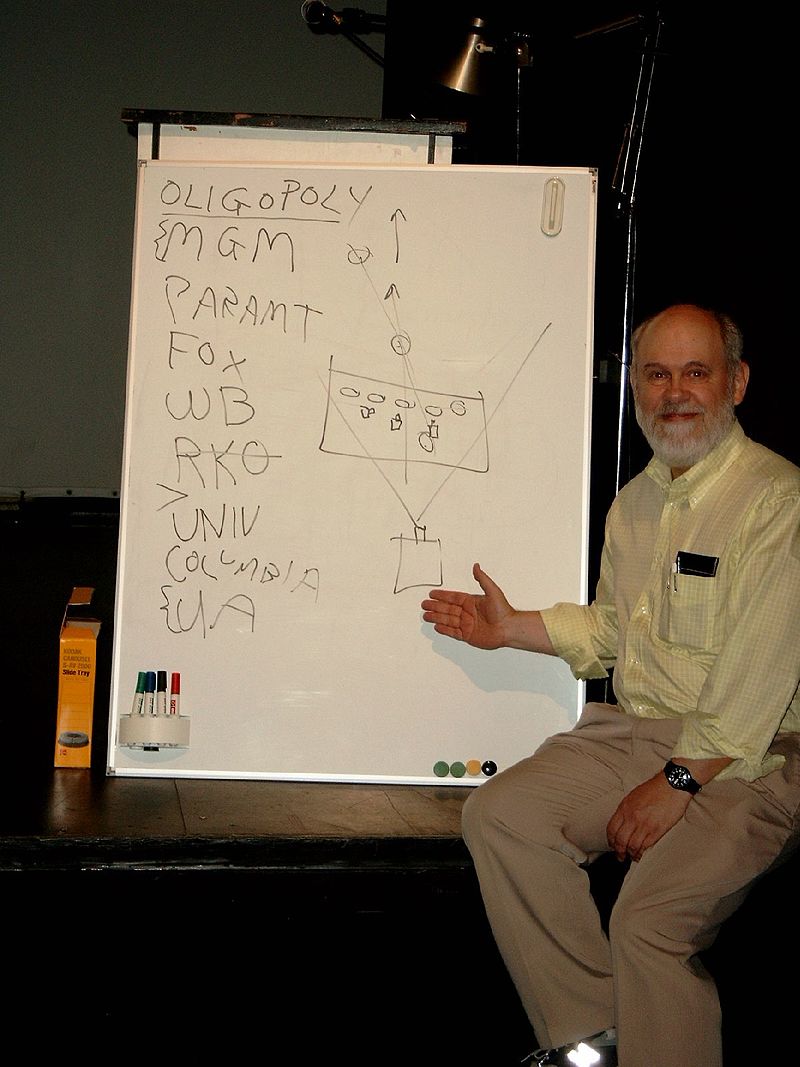

David Bordwell:

source: Wasily on Wiki

I love reading stuff like this, in the hopes of improving my craft at storytelling, but as Cutting notes:

Filmmaking is a craft. As a craft, its required skills are not easily penetrated in a conscious manner.

In the end you gotta learn by feel. We can feel when a story is right, or when it’s not right. I reckon you can learn more about movie story, and storytelling in general, by telling your story to somebody aloud and noticing when you “lose” them than you can by reading all of Brodwell. Anyone who’s pitched anything can probably remember moments when you knew you had them, or spontaneously edited because you could feel you were losing them.

Still, it’s fun to break apart human cognition and I look forward to more articles from Cognitive Science and am grateful they are free!

Another paper cited in this article is “You’re a good structure, Charlie Brown: the distribution of narrative categories in comic strips” by N Cohn.

Thanks to Larry G. for putting me on to this one.

Movie Reviews: The Favourite, Mary Queen of Scots, Schindler’s List

Posted: December 14, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, everyone's a critic, film, movies, the California Condition, Uncategorized Leave a comment

Finding myself with an unexpectedly free afternoon, I went to see The Favourite at the Arclight,

You rarely see elderly people in central Hollywood, but they’re there at the movies at 2pm. While we waited for the movie to start, there was an audible electrical hum. The Arclight person introduced the film, and then one of the audience members shouted out “what’re you gonna do about the grounding hum?”

The use of the phrase “grounding hum” rather than just “that humming sound” seemed to baffle the Arclight worker. Panicked, she said she’d look into it, and if we wanted, we could be “set up with another movie.”

After like one minute I took the option to be set up with another movie because the hum was really annoying. Playing soon was Mary Queen of Scots.

Reminded as I thought about it of John Ford’s quote about Monument Valley. John Ford assembles the crew and says, we’re out here to shoot the most interesting thing in the world: the human face.

Both Saoirse Ronan and Margot Robbie have incredible faces. It’s glorious to see them. The best parts of this movie were closeups.

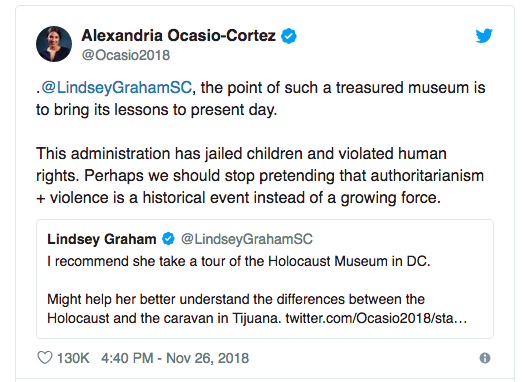

Next I saw Schindler’s List.

This movie has been re-released, with an intro from Spielberg, about the dangers of racism.

This movie knocked my socks off. I forgot, since the last time I saw it, what this movie accomplished.

When the movie first came out, the context in which people were prepared for it, discussed it, saw it, were shown it in school etc took it beyond the realm of like “a movie” and into some other world of experience and meaning.

I feel like I saw this movie for the first time on VHS tapes from the public library, although I believe we were shown the shower scene at school.

My idea in seeing it this time was to see it as a movie.

How did they make it? How does it work? What’s accomplished on the level of craft? Once we’ve handled the fact that we’re seeing a representation of the Holocaust, how does this work as a movie?

It’s incredible. The craft level accomplishment is on the absolute highest level.

Take away the weight with which this movie first reached us, with what it was attempting. Just approach it as “a filmmaker made this, put this together.”

Long, enormous shots of huge numbers of people, presented in ways that feel real, alive. Liam Neeson’s performance, his mysteries, his charisma, his ambiguity. We don’t actually learn that much about Oscar Schindler. So much is hidden.

Ralph Fiennes performance, the humanity, the realness he brings to someone whose crimes just overload the brain’s ability to process.

The moving parts, the train shots, the wide city shots. Unreal accomplishment of filmmaking.

Some thoughts:

- water, recurring as an image, theme in the movie.

- there are a bunch of scenes of just factory action, people making things with tools and machines. that was the cover. was not the Holocaust an event of the factory age, a twisted branch of Industrial Revolution and efficiency metric spirit?

- reminded that people didn’t know, when it began, “we’re in The Holocaust, this is the Holocaust.” It built. It got worse and worse. there were steps and stages along the way.

- what happened in the the Holocaust happened in a particular time and place in history, focused in an area of central and eastern Europe that had its own, centuries long, context for what you were, who belonged where, history, which tribes go where, what race or nationality meant, how these were understood. Göth’s speech about how the centuries of Jewish history in Kraków will become a rumor. I felt like this movie kind of captured and helped explain some of that, without a ton of extra labor.

- In a way Schindler could almost be seen as like a comic character. He didn’t start his company to save Jews. He starts it to make money from cheap labor. He’s a schemer who sees an opportunity. A rascal out to make a quick buck, a con man and shady dealer who ended up in the worst crime in history, an honest crook who finds he’s in something of vastness and evil beyond his ability to even comprehend.

- There is a scene in this movie that could almost be called funny, or at least comic, when Oscar Schindler (Neeson) tries to explain to Stern (Ben Kingsley) the good qualities of the concentration camp commandant Göth that nobody ever seems to mention!

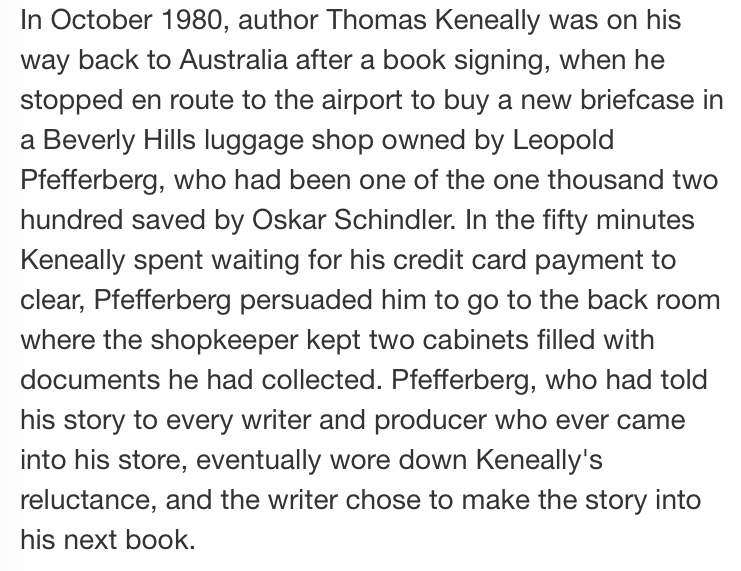

- Kenneally’s story of how he heard about Schindler:

- The theme of sexuality, Goth’s sexuality, Schindler’s, what it means to love and express your nature versus trying to suppress and kill. Spielberg is not really known for having tough explorations of sexuality in his films but I’d say he took this one pretty square on with a lot bravery?

- if I had a criticism it was maybe that the text on the little intermediary passages that appear on screen a few times and explain the context felt not that clear and kind of unnecessary.

- I feared this movie would have a kind of ’90s whitewash, I felt maybe takes exist, the “actually Schindler’s List is BAD” take is out there, with the idea being that Spielberg put in too much sugar with the medicine which when we talk about the Shoah, unspeakable, unaddressable, is somehow wrong, but damn. I was glad for the sugar myself and I don’t think Spielberg looked away. The Holocaust occurred in a human context, and human contexts, no matter how dark, always have absurdity.

- the scene, for instance, were the Nazis burn in an enormous pyre the months-buried, now exhumed bodies of thousands of people executed during the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto, Spielberg took us as close to the mouth of the abyss as you’re gonna see at a regular movie theater.

What does it mean that Spielberg made a movie about the Holocaust and the two leads are both handsome Nazis?

*As a boy I was attracted to the history of Britain and Ireland as well as Celtic and Anglo-Saxon peoples in America. The peoples of those islands recorded a dramatic history that I felt connected to. They also developed a compelling tradition of telling these history stories with as much drama and excitement as possible eg. Shakespeare.

At a library book sale, I bought, for 50 cents a volume, three biographies from a numbered set from like 1920 of “notable personages,” something like that.

These just looked like the kind of books that a cool gentleman had. Books that indicated status and intelligence.

One of this set that I got was Hernando Cortes. I started that one, but even at that tender age I perceived Cortes was not someone to get behind. The biography had a pro-Cortes slant I found distasteful.

Another volume was about Mary Queen of Scots.

Just on her name, really, I started reading that one.

Mary Queen of Scots’ life was a thrilling story, and this one was melodramatically told. Affairs, murder plots, insults, rumor, execution.

Sometime thereafter, at school, we were all assigned like a book report. To read a biography, any biography, and write a report about it.

Since I’d already read Mary’s biography, I picked her.

As it happened, I overheard my dad confusedly ask my mom why, of all people on Earth, I’d chosen Mary Queen of Scots as the topic for my biography project. My dad did not know the backstory, which my mom patiently explained.

My dad’s reaction on hearing I’d picked Mary Queen of Scots, while not as harsh as Kevin Hart’s imagined reaction on hearing his son had a dollhouse, helps me to understand where Kevin Hart was coming from. Confusion, for starters. Upsetness.

At the time the guys I thought were really heroes were probably like JFK and Hemingway.

Hollywood: A Very Short Introduction

Posted: September 16, 2018 Filed under: film, Hollywood, movies Leave a commentThe sequence beginning around 3:30 is captivating.

What’s going on here? We are right to be confused:

So I’m told in this one:

Some of the Oxford Very Short Introduction books aren’t that helpful. Some are great. I got a lot out of this one. I didn’t know this story about Lucille Ball, for instance:

The Gambler (2014)

Posted: September 12, 2018 Filed under: business, film, money, movies, screenwriting, shakespeare, writing 1 Comment

Saw this clip on some retweet of this fellow’s Twitter.

I was struck by

- the bluntness and concision of the advice

- the fact that the advice contains a very specific investment strategy down to what funds you should be in (80% VTSAX, 20% VBTLX)

- the compelling performance of an actor I’d never seen opposite Wahlberg (although I’d say it drops off at “that’s your base, get me?”)

It appeared this was from the 2014 film The Gambler

The film is interesting. Mark Wahlberg plays a compulsive gambler and English professor. There are some extended scenes of Wahlberg lecturing his college undergrads on Shakespeare, Camus, and his own self-absorbed theories of literature, failure, and life. The character is obnoxious, self-pitying, logorrheic and somewhat unlikeable as a hero. Nevertheless his most attractive student falls in love with him. William Monahan, who won an Oscar for The Departed, wrote the screenplay. The film itself is a remake of 1974 movie directed by James Toback, in which James Caan plays the Mark Wahlberg role.

Here’s the interesting thing. Watching the 2016 version, I realized the speech I’d seen on Twitter that first caught my attention is different. The actor’s different — in the movie I watched it’s John Goodman.

What happened here? Had they recast the actor or something? The twitterer who put it up is from South Africa, did they release a different version of the movie there?

Did some investigating and found the version I saw was made by this guy, JL Collins, a financial blogger.

Here’s a roundup of his nine basic points for financial independence.

He did a pretty good job as an actor I think! I believe the scene in the movie would be strengthened from the specificity of his advice. And the line about every stiff from the factory stiff to the CEO is working to make you richer is cool, maybe an improvement on the script as filmed. I’ll have to get this guy’s book.

It would make a good commercial for Vanguard.

VTSAX vs S&P 500:

Readers, what does the one to one comparison of JL Collins and John Goodman teach us about acting?

Darkest Hour

Posted: August 20, 2018 Filed under: film, history Leave a comment

This movie is on HBO this month. I saw the movie in the theater and thought it was pretty good. It really captured the batty, Lewis Carroll eccentricity element of Churchill and the British Parliament.

But one thing that I was wondering about was the title. I remembered a story I’d heard years ago about Churchill visiting Harrow in 1941. The schoolboys sang a new verse to an old song:

When Churchill visited Harrow on October 29 to hear the traditional songs again, he discovered that an additional verse had been added to one of them. It ran:

“Not less we praise in darker days

The leader of our nation,

And Churchill’s name shall win acclaim

From each new generation.

For you have power in danger’s hour

Our freedom to defend, Sir!

Though long the fight we know that right

Will triumph in the end, Sir!”

Churchill didn’t care for the word darker. In his speech to the school he said:

You sang here a verse of a School Song: you sang that extra verse written in my honour, which I was very greatly complimented by and which you have repeated today. But there is one word in it I want to alter – I wanted to do so last year, but I did not venture to. It is the line: “Not less we praise in darker days.”

I have obtained the Head Master’s permission to alter darker to sterner. “Not less we praise in sterner days.”

Do not let us speak of darker days: let us speak rather of sterner days. These are not dark days; these are great days – the greatest days our country has ever lived; and we must all thank God that we have been allowed, each of us according to our stations, to play a part in making these days memorable in the history of our race.

Getting all that from the National Churchill Museum.

I believe this Wikipedia page is inaccurate:

“The Darkest Hour” is a phrase coined by British prime minister

Did he coin this phrase?

Winston Churchill to describe the period of World War II between the Fall of France in June 1940 and the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 (totaling 363 days, or 11 months and 28 days), when the British Empire stood alone (or almost alone after the Italian invasion of Greece) against the Axis Powers in Europe.

Perhaps he uses it in his volumes of history, which I don’t have at hand. But that’s not the source Wiki cites. In the cited “Finest Hour” speech, Churchill did use the phrase “darkest hour,” but to refer to what a sad period this was in French history:

The House will have read the historic declaration in which, at the desire of many Frenchmen-and of our own hearts-we have proclaimed our willingness at the darkest hour in French history to conclude a union of common citizenship in this struggle.

I bought screenwriter Anthony McCarten’s book:

on Kindle and did a search. Unless I’m missing something, I can find no other time in the book where Churchill himself is quoted using the phrase “darkest hour.”

So, the movie about Churchill uses for its title a term that Churchill himself specifically asked people not to use.

My question as always: is this interesting?

Mission: Impossible: Fallout

Posted: July 30, 2018 Filed under: film, movies 1 Comment

Question about this film, if you’ve seen it:

(and don’t get me wrong, I had a good time)

why was a high-altitude parachute jump the best way to get into Paris?

Classical KUSC / soundless WW2 footage

Posted: July 21, 2018 Filed under: film, music, WW2 Leave a commentfound that playing Smithsonian Channel’s The Pacific War In Color while KUSC our local classical station was coming out of my old radio created a cool effect.

RIP Stanley Cavell

Posted: June 20, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, film, writing 1 Comment

Here is an obituary of the Harvard philosopher, who has left this Earth. To be honest with you, most of Cavell’s work is over my head. Much of it seems to deal with the ultimate breakdown of language and the difficulty of meaning anything.

Cavell wrote the epigraph for my favorite book:

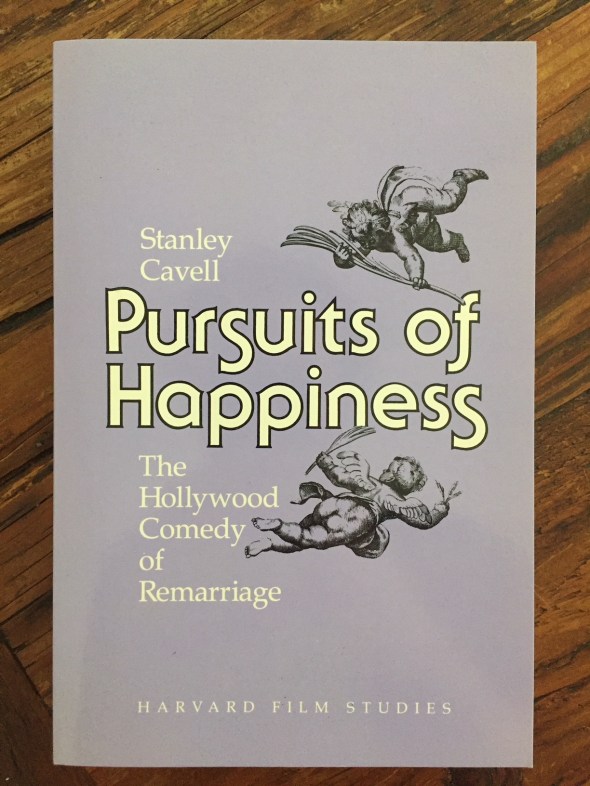

and at some point, somebody (Etan?) recommended I check out:

which meant a lot to me.

This book is a study of seven screwball comedies:

The Lady Eve

It Happened One Night

Bringing Up Baby

The Philadelphia Story

His Girl Friday

Adam’s Rib

The Awful Truth

These Cavell calls comedies of remarriage. They’re stories (mostly) where the main characters have a history, and the plots involve the tangles as they struggle, fight, and reconnect.

What the book really gets it is: what is revealed about us or our society when we look at what we find pleasing and appropriate in romantic comedies? Why do we root for Cary Grant instead of Jimmy Stewart in The Philadelphia Story for instance?

It’s fun to watch these movies and read this book.

It’s dense for sure. I read it before the Age of Phones, not sure how I’d fair today. But I still think about insights from it.

At one point Cavell says (in a parenthetical!):

I do not wish, in trying for a moment to resist, or scrutinize, the power of Spencer Tracy’s playfulness, to deny that I sometimes feel Katherine Hepburn to lack a certain humor about herself, to count the till a little too often. But then I think of how often I have cast the world I want to live in as one in which my capacities for playfulness and for seriousness are not used against one another, so against me. I am the lady they always want to saw in half.

Cool phrase.

RIP to a real one!

Oscars Conspiracy Theory

Posted: March 2, 2017 Filed under: film, the California Condition Leave a comment

Let me be clear I don’t really believe this conspiracy. But I DID think of it.

If Moonlight had won, award would’ve gone to Adele Romanski, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner, the producers. That’s who would’ve accepted and given the speech. White producers winning for a movie directed by a black man about black characters would’ve been a terrible look for an Academy terrified by its own dismal record on representation and diversity. So, the Academy deliberately staged a mixup. This had the added benefit of helping the Oscars’ other big problem, people tuning out of the telecast, by making wild unpredictable surprises a part of the experience — “you gotta watch to the very end to see what happens!”

Again, I don’t believe this theory, there’s no evidence for it and significant evidence against it. Still sharing it.

Groovy opening

Posted: May 3, 2016 Filed under: adventures, film, Italy, movies, music Leave a comment

Atypical cinematic take on Boston

Posted: March 10, 2016 Filed under: Boston, film, New England Leave a commentThe other day I was home sick from work, and Field of Dreams was on TV. Readers will recall Ray Kinsella goes to Boston to track down Terence Mann. What a specific take on Boston! No one is Irish or has much of an accent, and the biggest Red Sox fan is a black guy. Kudos to director Phil Alden Robinson for taking things deeper.

Ridiculous

Posted: January 22, 2016 Filed under: actors, film, Hollywood, the California Condition Leave a comment

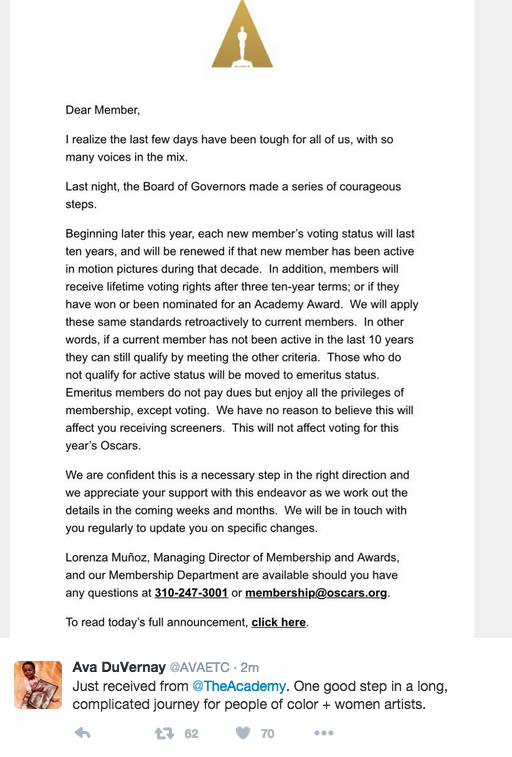

Amazing letter from The Academy. Imagine sending out an email in which you described your own organization’s action of slightly adjusting membership rules as “courageous.”