Advances in Cormac studies

Posted: April 9, 2018 Filed under: America Since 1945, Texas, writing Leave a comment

Morrow quotes McCarthy as saying that “even people who write well can’t write novels… They assume another sort of voice and a weird, affected kind of style. They think, ‘O now I’m writing a novel,’ and something happens. They write really good essays… but goddamn, the minute they start writing a novel they go crazy“

In early 2008 Texas State University announced they’d acquired Cormac McCarthy’s papers. The next year they made them available to scholars. Now two books based on rummaging around in these notes have appeared.

This one, by Michael Lynn Crews, explores the literary influences McCarthy drew on, which authors and books he had quotes from buried in his papers.

The quote about novelists going crazy is from a letter exchange McCarthy was having re: Ron Hanson’s novel Desperadoes, which McCarthy admired.

This one, by Daniel Robert King, takes more of a semi-biographical approach, tracing out what we can learn about McCarthy from his correspondence with agents and editors. A sample:

Bought these books because it gives confidence to observe that somebody whose writing sounds like it emerged pronounced from the cliffs like some kind of Texas Quran had to work and revise and toss stuff and chisel to get there.

From these books it is clear:

- McCarthy is a meticulous and patient rewriter

- it took decades for his work to gain any significant recognition

- he was helped with seeming love and care by editor Albert Erskine.

- he was patient, open, yet confident in editorial correspondence

These books are not necessary for the casual personal library, but if you enjoy gnawing on literary scraps, recommend them both. From King:

However, in this same letter, he acknowledges that “the truth is that the historical material is really – to me – little more than a framework upon which to hang a dramatic inquiry into the nature of destiny and history and the uses of reason and knowledge and the nature of evil and all these sorts of things which have plagued folks since there were folks.”

A Confederate General from Big Sur by Richard Brautigan

Posted: February 18, 2018 Filed under: Steinbeck, the California Condition, writing Leave a comment

It was during the second day of the Battle of the Wilderness. A. P. Hill’s brave but exhausted confederate troops had been hit at daybreak by Union General Hancock’s II Corps of 30,000 men. A. P. Hill’s troops were shattered by the attack and fell back in defeat and confusion along the Orange Plank Road.

Twenty-eight-year-old Colonel William Poague, the South’s fine artillery man, waited with sixteen guns in one of the few clearings in the Wilderness, Widow Tapp’s farm. Colonel Poague had his guns loaded with antipersonnel ammunition and opened fire as soon as A. P. Hill’s men had barely fled the Orange Plank Road.

The Union assault funneled itself right into a vision of scupltured artillery fire, and the Union troops suddenly found pieces of flying marble breaking their centers and breaking their edges. At the instant of contact, history transformed their bodies into statues. They didn’t like it, and the assault began to back up along the Orange Plank Road. What a nice name for a road.

On title alone this book had me. I’d never read Brautigan, cult hero of the age when the Army was giving LSD to draftees. This one came out in 1964.

Most of the book tells the story of the narrator living rough in Big Sur with Lee Mellon, who is convinced he’s descended from a Confederate general.

I met Mellon five years ago in San Francisco. It was spring. He had just “hitch-hiked” up from Big Sur. Along the way a rich queer stopped and picked Lee Mellon up in a sports car. The rich queer offered Lee Mellon ten dollars to commit an act of oral outrage.

Lee Mellon said all right and they stopped at some lonely place where there were trees leading back into the mountains, joining up with a forest way back in there, and then the forest went over the top of the mountains.

“After you,” Lee Mellon said, and they walked back into the trees, the rich queer leading the way. Lee Mellon picked up a rock and bashed the rich queer in the head with it.

At times reading this book felt like talking to a person who is on drugs when you yourself are not on drugs. By the end of this short book it felt little tedious. The semi-jokes seemed more like dodges.

Still, Brautigan has an infectious style.

Mallley says:

Like much of Brautigan’s work, Confederate General belongs, at least partly, to a broad category of American literature – stories dealing with a man going off alone (or two men going off together), away from the complex problems and frustrations of society into a simpler world closer to nature, whether in the woods, in the mountains, on the river, wherever.

For a more satisfying read on men going off away from the complex problems and frustrations of society in the same region, I might recommend:

or

but it’s short and alive. The few short passages about the Civil War were my favorite.

We left with the muscatel and went up to the Ina Coolbrith Park on Vallejo Street. She was a poet contemporary of Mark Twain and Brett Harte during that great San Francisco literary renaissance of the 1860s.

Then Ina Coolbrith was an Oakland librarian for thirty-two years and first delivered books into the hands of the child Jack London. She was born in 1841 and died in 1928: “Loved Laurel-Crowned Poet of California,” and she was the same woman whose husband took a shot at her with a rifle in 1861. He missed.

“Here’s to General Augustus Mellon, Flower of Southern Chivalry and Lion of the Battlefield!” Lee Mellon said, taking the cap off four pounds of muscatel.

We drank the four pounds of muscatel in the Ina Coolbrith Park, looking down Vallejo Street to San Francisco Bay and how the sunny morning was upon it and a barge of railroad cars going across to Marin County.

“What a warrior,” Lee Mellon said, putting the last 1/3 ounce of muscatel, “the corner,” in his mouth.

As for Brautigan:

According to Michael Caines, writing in the Times Literary Supplement, the story that Brautigan left a suicide note that simply read: “Messy, isn’t it?” is apocryphal.

Skiing

Posted: February 16, 2018 Filed under: Hemingway, Hemingway, sports, winter, women, writing Leave a comment

There were no ski lifts from Schruns and no funiculars; but there were logging trails and cattle trails that led up different mountain valleys to the high mountain country. You climbed on foot carrying your skis and higher up, where the snow was too deep, you climbed on seal skins that you attached to the bottoms of the skis. At the tops of mountain valleys there were the big Alpine Club huts for summer climbers where you could sleep and leave payment for any wood you used. In some you had to pack up your own wood, or if you were going on a long tour in the high mountains and the glaciers, you hired someone to pack wood and supplies up with you, and established a base. The most famous of these high base huts were the Lindauer-Hütte, the Madlener-Hause and the Wiesbadener-Hütte.

So says Hemingway in A Moveable Feast, “Winters in Schruns”

Skiing was not the way it is now, the spiral fracture had not become common then, and no one could afford a broken leg. There were no ski patrols. Anything you ran down from, you had to climb up to first, and you could run down only as often as you could climb up. That made you have legs that were fit to run down with.

And what did you eat, Hemingway?

We were always hungry and every meal time was a great event. We drank light or dark beer and new wines and wines that were a year old sometimes. The white wines were the best. For other drinks there was wonderful kirsch made in the valley and Enzian Schnapps distilled from mountain gentian. Sometimes for dinner there would be jugged hare with a rich red wine sauce, and sometimes venison with chestnut sauce. We would drink red wine with these even though it was more expensive than white wine, and the very best cost twenty cents a liter. Ordinary red wine was much cheaper and we packed it up in kegs to the Madlener-Haus.

What was the worst thing you remember?

The worst thing I remember of that avalanche winter was one man who was dug out. He had squatted down and made a box with his arms in front of his head, as we had been taught to do, so that there would be air to breathe as the snow rose up over you. It was a huge avalanche and it took a long time to dig everyone out, and this man was the last to be found. He had not been dead long and his neck was worn through so that the tendons and the bones were visible. He had been turning his head from side to side against the pressure of the snow. In this avalanche there must have been some old, packed snow mixed in with the new light snow that had slipped. We could not decide whether he had done it on purpose or if he had been out of his head. But there was no problem because he was refused burial in consecrated ground by the local priest anyway; since there was no proof he was a Catholic.

What else do you remember?

I remember the smell of the pines and the sleeping on the mattresses of beech leaves in the woodcutters’ huts and the skiing through the forest following the tracks of hares and of foxes. In the high mountains above the tree line I remember following the track of a fox until I came in sight of him and watching him stand with his forefoot raised and then go on carefully to sop and then pounce, and the whiteness and the clutter of a ptarmigan bursting out of the snow and flying away and over the ridge.

And, did you, btw, sleep with your wife’s best friend?

The last year in the mountains new people came deep into our lives and nothing was ever the same again. The winter of the avalanches was like a happy and innocent winter in childhood compared to that winter and the murderous summer that was to follow. Hadley and I had become too confident in each other and careless in our confidence and pride. In the mechanics of how this was penetrated I have never tried to apportion the blame, except my own part, and that was clearer all my life. The bulldozing of three people’s hearts to destroy one happiness and build another and the love and the good work and all that came out of it is not part of this book. I wrote it and left it out. It is a complicated, valuable, instructive story. How it all ended, finally, has nothing to do with this either. Any blame in that was mine to take and possess and understand. The only one, Hadley, who had no possible blame, ever, came well out of it finally and married a much finer man that I ever was or could hope to be and is happy and deserves it and that was one good and lasting thing that came out of that year.

Google, show me Schruns:

PTA

Posted: January 19, 2018 Filed under: actors, writing Leave a comment

Liked this quote from PTA’s AMA where he says the script is “just a temporary thing”

Hemingway Writing Advice

Posted: November 13, 2017 Filed under: Florida, Hemingway, writing, writing advice from other people 2 Comments

one of the descendants of Hemingway’s messed-up, inbred, extra-toe cats in Key West

In a 1935 Esquire piece, Hemingway, already playing the preening dickhead, gives some writing advice that I think is clear-eyed and well-expressed.

Writing room in Hem house in Key West

The setup is a young man has come to visit him in Key West, and Hemingway has given him the nickname Maestro because he played the violin.

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise. Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Then get in somebody elseʼs head for a change If I bawl you out try to figure out what Iʼm thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Donʼt just think who is right. As a man things are as they should or shouldnʼt be. As a man you know who is right and who is wrong. You have to make decisions and enforce them. As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.

Mice: All right.

Y.C.: Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Donʼt be thinking what youʼre going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe. You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice. When youʼre in town stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars. There are a thousand ways to practice. And always think of other people.

Mice: Do you think I will be a writer?

Y.C.: How the hell should I know? Maybe youʼve got no talent. Maybe you canʼt feel for other people. Youʼve got some good stories if you can write them. Mice: How can I tell?

Y.C.: Write. If you work at it five years and you find youʼre no good you can just as well shoot yourself then as now.

Mice: I wouldnʼt shoot myself.

Y.C.: Come around then and Iʼll shoot you.

Mice: Thanks.

This article is behind a paywall at Esquire but I found it reprinted on the website of Diana Drake, who has story by credit on the film What Women Want.

Boston (England)

Posted: October 27, 2017 Filed under: Boston, New England, writing Leave a comment

There’s a lot of crime fiction about Boston, America, but is there any about Boston, UK? I went looking and was directed to the works of Colin Watson, who writes about a fictional town, Flaxborough, which is based on Boston (UK version)?

I can’t say it was totally compelling to me but cheers to Colin Watson.

Watson was the first person to successfully sue Private Eye for libel, for an article in issue 25 when he objected to being described as: “the little-known author who . . . was writing a novel, very Wodehouse but without the jokes”. He was awarded £750.

Critics on critics on critics

Posted: October 17, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, art history, books, writing Leave a comment

This review in the New York Times, by Vivan Gornick of Adam Gopnik’s “At The Strangers’ Gate” caught my attention.

Critics have taken aim on Adam Gopnik before. To which New Yorker editor David Remnick says:

‘The day any of these people write anything even remotely as fine and intelligent as Adam Gopnik will be a cold day in hell.'”

The key to this memoir might be when the author reveals he graduated high school at age fourteen. He’s a boy genius.

This is kind of Young Sheldon the book.

The book has some good stories in it. Adam Gopnik tells about how a guy who came to one of his lectures on Van Gogh. This guy had an axe to grind and it was this: why did Vincent never paint his brother Theo?

My favorite part of the book was Gopnik’s discussion of Jeff Koons. Gopnik is illuminating on the topic of Jeff Koons. Here is Koons talking to Gopnik at a party.

(I added the potato because while it may not be strictly legal to electronically reproduce pages of books, if I include them in an original work of art, that’s gotta be allowed, right?)

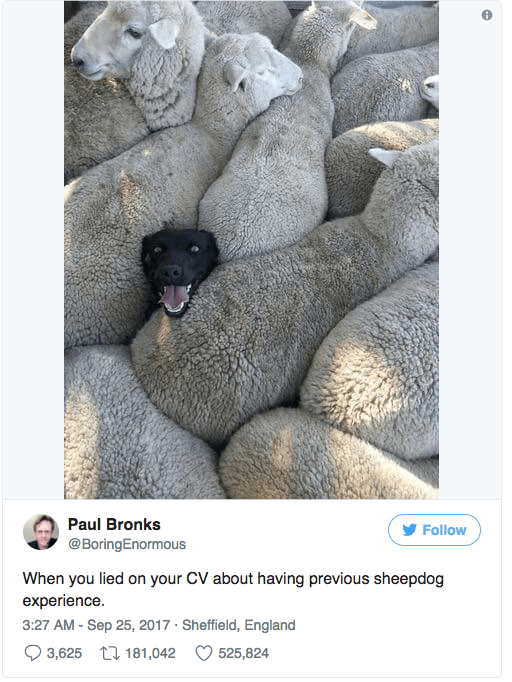

When you lied on your CV

Posted: October 12, 2017 Filed under: animals, Fate, writing Leave a comment

The source of that photo is Tasmanian sheep farmer Charlie Mackinnon, who said of the dog:

She was an absolute legend, worked all day.

Funny story told in Jay McInerney Paris Review interview:

MCINERNEY

I felt like I had really arrived because—well, it was The New Yorker. But it was the fact-checking department. I wanted to be in the fiction pages, but still. It actually paid pretty well, and I was seeing great writers like John McPhee and John Updike coming to visit William Shawn. J. D. Salinger was still calling on the phone. There was a terrific buzz about the place. But it was also a little depressing. There were all these unwritten rules. Like, for instance, if you were a fact-checker, you didn’t speak to an editor or writer in the hall—it just wasn’t done. Also, it turned out I wasn’t very good at it. And ten months after I got there, I was fired, and left ingloriously with my tail between my legs.

INTERVIEWER

How bad were you?

MCINERNEY

My biggest mistake was to have lied on my résumé and said that I was fluent in French, which I wasn’t. So when the time came to check a Jane Kramer piece on the French elections, it was assigned to me, and I had to call France and talk to a lot of people who didn’t speak English. That was really my downfall. And of course I couldn’t admit to anyone that I had this problem. Jane Kramer discovered factual errors just before publication. Nothing earth shattering, but you would think that I had . . .

Bellow

Posted: October 10, 2017 Filed under: Chicago, writing 3 Comments

Bracing for Amis too is a late essay of Bellow’s, ‘Wit Irony Fun Games’ – ‘quite possibly the last thing he ever wrote’ – that insists that ‘most novels have been written by ironists, satirists, and comedians’. Amis concludes, ‘The novel is comic because life is comic.’

Readin’ that line in this review of Martin Amis, The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump – Essays and Reportage, 1986–2016, by Christian Lorentzen over on Literary Review

So I says, let’s get a copy of this late essay of Bellow’s and see what he has to say. I’ve never read much Saul Bellow.

Sure enough it’s pretty good! Here in “Wit Irony Fun Games” he talks about Lincoln’s humor:

This, in an essay about FDR, gives backstory I didn’t know to the story of the attempted assassination:

In this essay, Bellow says his famously controversial comment about “who’s the Tolstoy of the Zulus” was all a misunderstanding:

He likes Zulus, and Papuans as well:

Papuans probably have a better grasp of their myths than most educated Americans have of their own literature. But without years of study we can’t begin to understand a culture very different from our own. The fair thing,, therefore, is to make allowance for what we outsiders cannot hope to fathom in another society and grant that, as members of the same species, primitive men are as mysterious or as monstrous as any other branch of humankind.

In your eye, cop!

Posted: September 15, 2017 Filed under: writing 1 CommentINTERVIEWER

When did you begin reading adult fiction?

KING

In 1959 probably, after we had moved back to Maine. I would have been twelve, and I was going to this little one-room schoolhouse just up the street from my house. All the grades were in one room, and there was a shithouse out back, which stank. There was no library in town, but every week the state sent a big green van called the bookmobile. You could get three books from the bookmobile and they didn’t care which ones—you didn’t have to take out kid books. Up until then what I had been reading was Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, and things like that. The first books I picked out were these Ed McBain 87th Precinct novels. In the one I read first, the cops go up to question a woman in this tenement apartment and she is standing there in her slip. The cops tell her to put some clothes on, and she grabs her breast through her slip and squeezes it at them and says, “In your eye, cop!” And I went, Shit! Immediately something clicked in my head. I thought, That’s real, that could really happen. That was the end of the Hardy Boys. That was the end of all juvenile fiction for me. It was like, See ya!

(Stephen King over at the Paris Review)

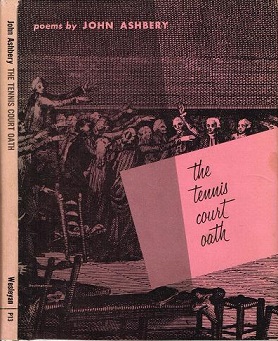

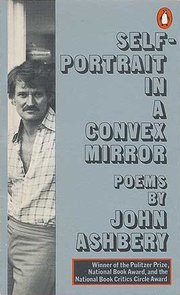

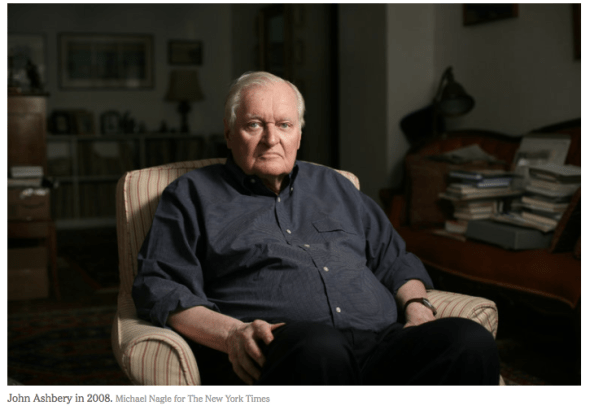

John Ashberry

Posted: September 7, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing Leave a commentI’d rather read John Ashberry’s obituary than any of his poems. This is because like most people I prefer story to poetry.

He once wrote poems in French and then translated them back into English in order to avoid customary word associations. (The poems are called, of course, “French Poems.”)

In an interview with The Times in 1999, Mr. Ashbery recalled that he and some childhood playmates “had a mythical kingdom in the woods.”

“Then my younger brother died just around the beginning of World War II,” he added. “The group dispersed for various reasons, and things were never as happy or romantic as they’d been, and my brother was no longer there.” He continued, “I think I’ve always been trying to get back to this mystical kingdom.”

Houellebecq

Posted: June 22, 2017 Filed under: writing Leave a comment

found here

from the Paris Review interview with Michel Houllebecq

INTERVIEWER

You have a bit of a scientific background. After high school, you studied agronomy. What is agronomy?

HOUELLEBECQ

It’s everything having to do with the production of food. The one little project I did was a vegetation map of Corsica whose purpose was to find places where you could put sheep. I had read in the school brochure that studying agronomy can lead to all sorts of careers, but it turns out that was ridiculous. Most people still end up in some form of agriculture, with a few amusing exceptions. Two of my classmates became priests, for example.

INTERVIEWER

Did you enjoy your studies?

HOUELLEBECQ

Very much. In fact, I almost became a researcher. It’s one of the most autobiographical things in The Elementary Particles. My job would have been to find mathematical models that could be applied to the fish populations in Lake Nantua in the Rhône-Alpes region. But strangely, I turned it down, which was stupid, actually, because finding work afterward was impossible.

INTERVIEWER

In the end you went to work as a computer programmer. Did you have previous experience?

HOUELLEBECQ

I knew nothing about it. But this was back when there was a huge need for programming and no schools to speak of. So it was easy to get into. But I loathed it immediately.

INTERVIEWER

So what made you write your first novel, Whatever, about a computer programmer and his sexually frustrated friend?

HOUELLEBECQ

I hadn’t seen any novel make the statement that entering the workforce was like entering the grave. That from then on, nothing happens and you have to pretend to be interested in your work. And, furthermore, that some people have a sex life and others don’t just because some are more attractive than others. I wanted to acknowledge that if people don’t have a sex life, it’s not for some moral reason, it’s just because they’re ugly. Once you’ve said it, it sounds obvious, but I wanted to say it.

Talking about his novel The Possibility of An Island:

INTERVIEWER

Why did you make your main character a comedian?

HOUELLEBECQ

The character came from two things. First of all, I went to a resort in Turkey and there was one of those talent shows produced by the guests. There was this girl—she must have been fifteen—who was doing Céline Dion and clearly for her, this was very, very important. I said to myself, Man, this girl is really going for it. And it’s funny because the next day, she was sitting alone at the breakfast table and I thought, Already the solitude of the star! I sensed that something like that can decide an entire life. So the comedian has a similar experience. He discovers all of sudden that he can make whole crowds laugh and it changes his life. The second thing was that I knew a woman who was editor in chief of a magazine and she was always inviting me to these hip events with Karl Lagerfeld, for example. I wanted to have someone who was part of that world.

On Anglo-Saxons (apparently including the Irish) and Americans:

INTERVIEWER

And what do you think of this Anglo-Saxon world?

HOUELLEBECQ

You can tell that this is the world that invented capitalism. There are private companies competing to deliver the mail, to collect the garbage. The financial section of the newspaper is much thicker than it is in French papers.

The other thing I’ve noticed is that men and women are more separate. When you go into a restaurant, for example, you often see women eating out together. The French from that point of view are very Latin. A single-sex dinner would be considered boring. In a hotel in Ireland, I saw a group of men talking golf at the breakfast table. They left and were replaced by a group of women who were discussing something else. It’s as if they’re separate species who meet occasionally for reproduction. There was a line I really liked in a novel by Coetzee. One of the characters suspects that the only thing that really interests his lesbian daughter in life is prickly-pear jam. Lesbianism is a pretext. She and her partner don’t have sex anymore, they dedicate themselves to decoration and cooking.

Maybe there’s some potential truth there about women who, in the end, have always been more interested in jam and curtains.

INTERVIEWER

And men? What do you think interests them?

HOUELLEBECQ

Little asses. I like Coetzee. He says things brutally, too.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve said that you possibly had an American side to you. What is your evidence for this?

HOUELLEBECQ

I have very little proof. There’s the fact that if I lived in an American context, I think I would have chosen a Lexus, which is the best quality for the price. And more obscurely, I have a dog that I know is very popular in the United States, a Welsh Corgi. One thing I don’t share is this American obsession with large breasts. That, I must admit, leaves me cold. But a two-car garage? I want one. A fridge with one of those ice-maker things? I want one too. What appeals to them appeals to me.

The Paris Review website has given me an awful lot.

Sappho

Posted: June 4, 2017 Filed under: women, writing Leave a comment

cool book.

I find Mary Barnard’s photo on the Oregonencyclopedia:

Her literary career took her from a childhood in the Oregon backwoods, where she often traveled with her timber-wholesaler father, to Reed College in Portland, where she was introduced to the classics and to the modern poetic revolution by Lloyd Reynolds.

Denis Johnson, Walt Whitman

Posted: May 29, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, heroes, writing Leave a commentWe’ve been thinking a lot about the glow of some of your poems, the visionary language seeping through parts of Angels, and the electric way in which the border between Fuckhead’s consciousness and the outside world is always being dissolved throughout Jesus’ Son. Could you talk a bit more about Whitman’s influence in your poetry and prose?

I’m not sure I could trace the lines of his influence on my language, particularly, or the way his work affects the strategies in my work, or anything like that. His expansive spirit, his generosity, his eagerness to love – those are the things that influence me, not just as a writer, but as a person. His introduction to LEAVES OF GRASS I take as a sort of personal manifesto, especially the passage:

This is what you shall do: Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body. . . .

found in this interview with Denis Johnson. Oddly or presciently or synchronistically enough I’d been looking for Denis Johnson materials as I did ever so often. How did this guy know this stuff? was what I was looking for as usual.

so good!

so good!

May I please recommend to you you have actor Will Patton read you the audiobook of:

I loved the experience so much I got into the full unabridged 23+ hours of:

Will Patton is such a gifted, subtle performer of audiobooks.

from a profile in AudioFile

Let’s give the last word to DJ:

I love McDonald’s double cheeseburgers and I don’t care if they’re made of pink slime and ammonia, I eat them all the time because they’re delicious.

Anne R. Dick

Posted: May 22, 2017 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing Leave a comment

Obit worth reading in the NY Times:

Bored with science fiction and unable to interest publishers in his mainstream novels, Dick quit writing to help his new wife in her jewelry business. He liked that even less, and so he pretended to work on a new novel. To make it look realistic, he said in a 1976 interview with Science Fiction Review, he had to start typing.

What emerged was “The Man in the High Castle.” It was dedicated, cryptically and not altogether favorably, to his wife, “without whose silence this book would never have been written.” (In the 1970s, Dick changed the dedication, dropping Anne Dick entirely.)

Ms. Dick said she saw only the pilot of the Amazon series, finding the Nazis a little too threatening.

If you are interested in hearing some ideas that flutter between profound and totally bonkers might I suggest:

How paranoia is natural:

How about this?:

Just a guy with a fragile mind hanging out reading Gestapo documents in German up at UC Berkeley:

In Sweden there’s a fashion brand called Filippa K and I thought it would be funny for someone to do a mashup Filippa K Dick.

But who has the time.

E. B. White in the Paris Review

Posted: April 26, 2017 Filed under: advice, writing Leave a commentFound here, what a great interview:

INTERVIEWER

You have wondered at Kenneth Roberts’s working methods—his stamina and discipline. You said you often went to zoos rather than write. Can you say something of discipline and the writer?

WHITE

Kenneth Roberts wrote historical novels. He knew just what he wanted to do and where he was going. He rose in the morning and went to work, methodically and industriously. This has not been true of me. The things I have managed to write have been varied and spotty—a mishmash. Except for certain routine chores, I never knew in the morning how the day was going to develop. I was like a hunter, hoping to catch sight of a rabbit. There are two faces to discipline. If a man (who writes) feels like going to a zoo, he should by all means go to a zoo. He might even be lucky, as I once was when I paid a call at the Bronx Zoo and found myself attending the birth of twin fawns. It was a fine sight, and I lost no time writing a piece about it. The other face of discipline is that, zoo or no zoo, diversion or no diversion, in the end a man must sit down and get the words on paper, and against great odds. This takes stamina and resolution. Having got them on paper, he must still have the discipline to discard them if they fail to measure up; he must view them with a jaundiced eye and do the whole thing over as many times as is necessary to achieve excellence, or as close to excellence as he can get. This varies from one time to maybe twenty.

The whole thing is good. White describes how he came to draw the above New Yorker cover, his only one. And he talks about the diaries of Francis Kilbert, which sure do sound interesting. (Jump to “4. Relations With Girls”)

Literary Life

Posted: April 17, 2017 Filed under: heroes, Texas, writing Leave a comment

Some real talk from Larry McMurtry

One of these days I’m going to rank all of McMurtry’s non-fiction books. They’re all chatty and great. This is the single best one.

Either Film Flam or Hollywood tells what it’s like to be friends with Diane Keaton and her mom.

McMurtry has really meant a lot to me. Here are some other posts about him:

about the time I heard him talk about Brokeback

Oh What A Slaughter and Sacagawea’s Nickname

More on Chikamatsu

Posted: April 8, 2017 Filed under: Japan, writing Leave a comment

Donald Keene isn’t having any of this Japan’s Shakespeare business:

A poem:

JCO on Twitter

Posted: April 1, 2017 Filed under: writing Leave a comment

a consistently wild experience.

Good sentence

Posted: April 1, 2017 Filed under: women, writing Leave a commentfrom Jean Rhys wikipedia page:

After her father died, in 1910, Rhys appeared to have experimented with the prospect of living as a demimondaine.