Interaction Ritual Chains

Posted: June 5, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, Christianity, heroes, history, marine biology, religion, sexuality Leave a comment Got interested in the sociologist Randall Collins via his blog, which I think Tyler Cowen linked to.

Got interested in the sociologist Randall Collins via his blog, which I think Tyler Cowen linked to.

Collins also wrote a book about violence.

If you find yourself in a bar fight, his main advice on avoiding “damage” seems to be:

1) maintain calm, steady eye contact.

2) speak in a calm clear assertive voice

3) assert emotional dominance, or at least hold your own, emotional dominance-wise.

Most of the damage gets done, says Collins (who watched hundreds of hours of tapes of bar fights) when you’ve already lost the emotional encounter. Even worse if there’s a crowd.

At the heart of Collins’ micro-sociological theory is the concept of “confrontational tension.” As people enter into an antagonistic interactional situation, their fear/tension is heightened. These emotions become a roadblock to violence, and so flight and stalemate often result. Actual violence only occurs when pathways around this roadblock can be found that lead people into a “tunnel of violence.” Collins identifies several pathways into this tunnel, the most dangerous of which is “forward panic.” In these situations, the confrontational tension builds up and is suddenly released so that it spills forward into atrocities ranging from the Rodney King beating to the My Lai massacre, the rape of Nanking, and the Rwandan genocide. Other ways around the stalemate of confrontational tension are to attack a weak victim (e.g., domestic violence) or to be encouraged by an audience (e.g., lynch mobs). Clearly, these pathways can also be combined, as when a schoolyard bully is encouraged by a crowd of classmates or when forward panic is stimulated by a group of bystanders.

Best posts from his blog, I’d say:

this one, on Napoleon and emotional energy.

this one, on Tank Man, is very interesting (although it goes against some other ideas I’ve heard, like Filip Hammar’s claim that it was well-known in his neighborhood of Beijing that Tank Man had been binge-drinking for days leading up to this event.)

this one, about fame, network bridging, and Lawrence of Arabia, is just fantastic.

So’s this one, about what we can learn from the gospel accounts of Jesus about charisma.

This one about Moby-Dick and bullfighting had some really interesting, new to me ideas.

I bought Professor Collins’ ebook, about emotional energy in Napoleon, Steve Jobs, and Alexander the Great. Lots of good stuff in there. And I got his magnum Interaction Ritual Chains. That’s a bit drier, but I’m learning a lot:

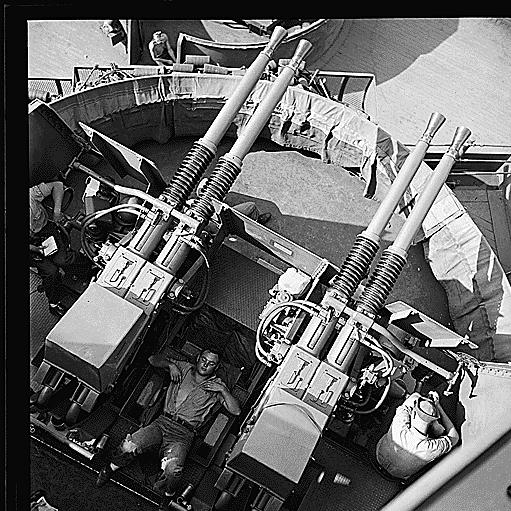

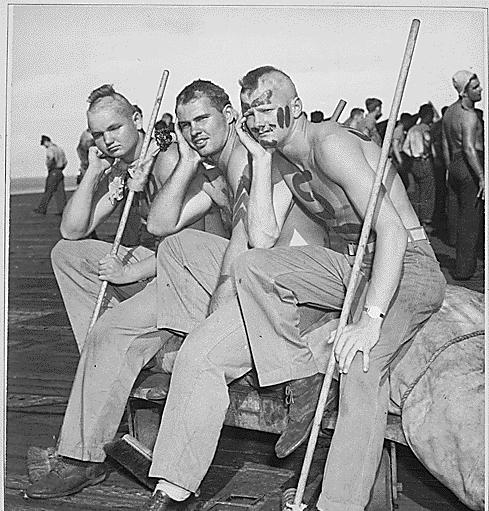

Record Group 80: Series: General Photographic File Of the Department of the Navy, 1943-1958

Posted: May 22, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, photography, the ocean, WW2 1 CommentFair to say I’m more interested than most people in old photos.

There are amazing collections of old photos in various US government archives, but they’re not always easy to find or sort through online.

Somehow I stumbled on this US Navy photographic archive.

“Pilot Tells of Dive-Bombing Wake Island in ready room of USS Yorktown (CV-10), 10/1943” is the title of that one.

“Pin-up girls at NAS Seattle, Spring Formal Dance. Left to right: Jeanne McIver, Harriet Berry, Muriel Alberti, Nancy Grant, Maleina Bagley, and Matti Ethridge.”, 04/10/1944″

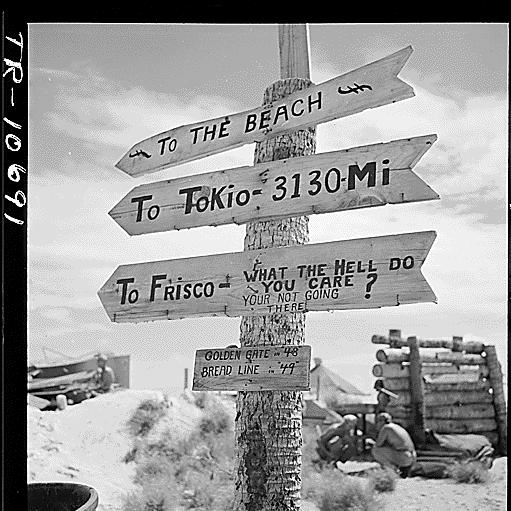

“Sign on Tarawa illustrates Marine humor and possible lack of optimism as to duration of war., 06/1944”

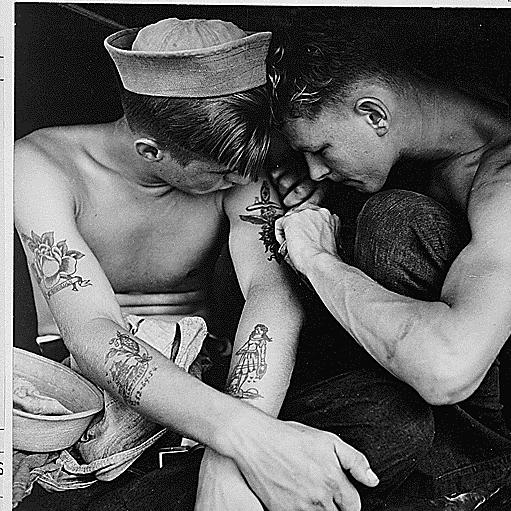

“Much tattooed sailor aboard the USS New Jersey, 12/1944”

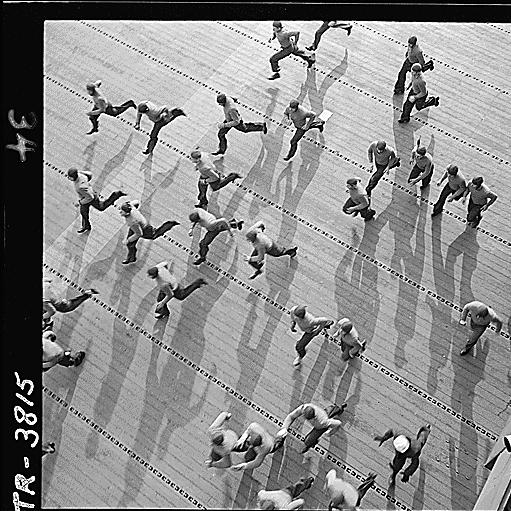

“Crewmen aboard USS Yorktown (CV-10) dash to stations as general quarters sound., 05/1943”

“Filipinos with their ‘bancas’ loaded with wares, paddle out to anchored destroyer to trade with crew., 06/1945”

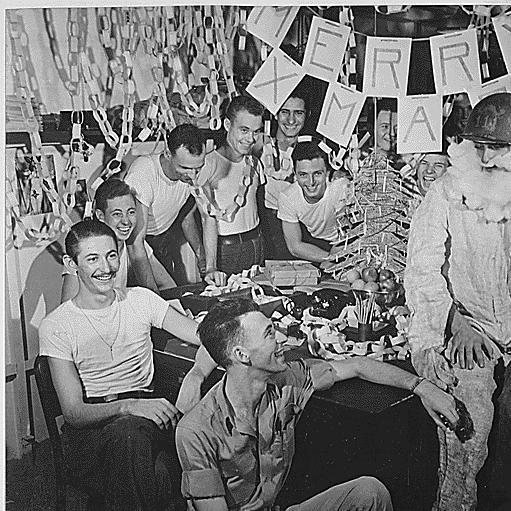

“Personnel of USS LEXINGTON celebrate Christmas with make-shift decorations and a firefighting, helmeted Santa Claus., 12/1944”

“Graves of U.S. Marines who died taking Tarawa, before headstones were prepared. In background are the first tents put up after occupation of the island., ca. 11/1943”

“Marines installing telephone lines under fire on Peleliu. In the background is seen part of famous Bloody Nose Ridge, scene of the fiercest fighting on Peleliu., 09/1944”

“Sailor asleep between 40mm guns on board the USS New Jersey (BB-62)., 12/1944”

“F6F taxies into position after landing on board the USS Lexington (CV-16)., ca. 11/26/1943”

“Sailor eating sandwich beneath propellers of torpedo being loaded aboard U.S. submarine at New London, Connecticut., 08/1943”

“Children in Naples, Italy. Little boy helps one-legged companion across street., 08/1944”

“Torpedomen relaxing beneath rows of deadly torpedoes in torpedo shop., ca. 05/1945”

Lord knows what you’d find if you dig through the archives in person. This is just what’s digitized and online.

Happy Memorial Day, errboddy.

“Lesser” McConaughey, or, On The Subject Of Great Acting

Posted: May 21, 2015 Filed under: actors, America Since 1945, movies, Texas, the California Condition Leave a comment

1995. I got my first big paycheck as an actor. I think it was 150 grand. The film was Boys on the Side and we’re shooting in Tucson, AZ and I have this sweet little adobe guest house on the edge of the Saguaro National Park. The house came with a maid. My first maid. It was awesome. So, I’ve got a friend over one Friday night and we’re having a good time and I’m telling her about how happy I am with my set up . The house. The maid. Especially, the maid. I’m telling her, “she cleans the place after I go to work, washes my clothes, the dishes, puts fresh water by my bed, leaves me cooked meals sometimes, and SHE EVEN PRESSES MY JEANS!” My friend, she smiles at me, happy for my genuine excitement over this “luxury service” I’m getting, and she says, “Well…that’s great…if you like your jeans pressed.”

I kind of looked at her, kind of stuttered without saying anything, you know, that dumb ass look you can get, and it hit me…

I hate that line going down my jeans! And it was then, for the first time, that I noticed…I’ve never thought about NOT liking that starched line down the front of my jeans!! Because I’d never had a maid to iron my jeans before!! And since she did, now, for the first time in my life, I just liked it because Icould get it, I never thought about if I really wanted it there. Well, I did NOT want it there. That line… and that night I learned something.

Just because you CAN?… Nah… It’s not a good enough reason to do something. Even when it means having more, be discerning, choose it, because you WANT it, DO IT because you WANT to.

I’ve never had my jeans pressed since.

I have been a McConaughey enthusiast for awhile. Proof: I saw Sahara and The Lincoln Lawyer* in the theater.

Here is a thing I admired then and continue to admire about McConaughey:

He treated ridiculous movies with utmost seriousness.

I don’t believe he treated Sahara with any less respect than True Detective, even though Sahara is crazy.

He brought pride and his fullest effort to those movies, the same as he would to any other movie. Failure To Launch, for example.

This is the mark of a true professional who practices his craft with great honor and seriousness

(but: could it also be the mark of someone who doesn’t know when something is ridiculous?)

The director, Richard Linklater, kept inviting me back to set each night, putting me in more scenes which led to more lines all of which I happily said YES to. I was having a blast. People said I was good at it, they were writing me a check for $325 a day. I mean hell yeah, give me more scenes, I love this!! And by the end of the shoot those 3 lines had turned into over 3 weeks work and “it was Wooderson’s ’70 Chevelle we went to get Aerosmith tickets in.” Bad ass.

Well, a few years ago I was watching the film again and I noticed two scenes that I really shouldn’t have been in. In one of the scenes, I exited screen left to head somewhere, then re-entered the screen to “double check” if any of the other characters wanted to go with me. Now, in rewatching the film, (and you’ll agree if you know Wooderson), he was not a guy who would ever say, “later,” and then COME BACK to “see if you were sure you didn’t wanna come with him..” No, when Wooderson leaves, Wooderson’s gone, he doesn’t stutter step, flinch, rewind, ask twice, or solicit, right? He just “likes those high school girls cus he gets older and they stay the same age.”

My point is, I should NOT have been in THAT scene, I should have exited screen left and never come back.

Matthew McConaughey is a truly great actor.

From a description of an interview with Cary Fukunaga:

Fukunaga took one of these opportunities to share a story about directing Matthew McConaughey, a health-nut and non-smoker, in an early scene where he takes long, audible drags of a cigarette. Fukunaga describes saying, “‘don’t make it look like a middle school girl smoking for the first time.’ And McConaughey went in the opposite direction, just Cheech and Chong-ing it.”

Bo Jackson ran over the goal line, through the end zone and up the tunnel — the greatest snipers and marksmen in the world don’t aim at the target, they aim on the other side of it.

We do our best when our destinations are beyond the “measurement,” when our reach continually exceeds our grasp, when we have immortal finish lines.

When we do this, the race is never over. The journey has no port. The adventure never ends because we are always on our way. Do this, and let them tap us on the shoulder and say, “hey, you scored.” Let them tell you “You won.” Let them come tell you, “you can go home now.” Let them say “I love you too.” Let them say “thank you.”

These quotes are from his amazing commencement speech at University of Houston:

The late and great University of Texas football coach Daryl Royal was a friend of mine and a good friend to many. A lot of people looked up to him. One was a musician named “Larry.” Now at this time in his life Larry was in the prime of his country music career, had #1 hits and his life was rollin’. He had picked up a habit snortin’ “the white stuff” somewhere along the line and at one particular party after a “bathroom break,” Larry went confidently up to his mentor Daryl and he started telling Coach a story. Coach listened as he always had and when Larry finished his story and was about to walk away, Coach Royal put a gentle hand on his shoulder and very discreetly said, “Larry, you got something on your nose there bud.” Larry immediately hurried to the bathroom mirror where he saw some white powder he hadn’t cleaned off his nose. He was ashamed. He was embarrassed. As much because he felt so disrespectful to Coach Royal, and as much because he’d obviously gotten too comfortable with the drug to even hide as well as he should.

Well, the next day Larry went to coach’s house, rang the doorbell, Coach answered and he said, “Coach, I need to talk to you.” Daryl said, “sure, c’mon in.”

Larry confessed. He purged his sins to Coach. He told him how embarrassed he was, and how he’s “lost his way” in the midst of all the fame and fortune and towards the end of an hour, Larry, in tears, asked Coach, “What do you think I should do?” Now, Coach, being a man of few words, just looked at him and calmly confessed himself. He said, “Larry, I have never had any trouble turning the page in the book of my life.” Larry got sober that day and he has been for the last 40 years.

Now: I loved reading this speech. Many important reminders about life:

Mom and dad teach us things as children. Teachers, mentors, the government and laws all give us guidelines to navigate life, rules to abide by in the name of accountability.

I’m not talking about those obligations. I’m talking about the ones we make with ourselves, with our God, with our own consciousness. I’m talking about the YOU versus YOU obligations. We have to have them. Again, these are not societal laws and expectations that we acknowledge and endow for anyone other than ourselves. These are FAITH based OBLIGATIONS that we make on our own.

Not the lowered insurance rate for a good driving record, you will not be fined or put in jail if you do not gratify the obligations I speak of — no one else governs these but you.

They’re secrets with yourself, private council, personal protocols, and while nobody throws you a party when you abide by them, no one will arrest you when you break them either. Except yourself. Or, some cops who got a “disturbing the peace” call at 2:30 in the morning because you were playing bongos in your birthday suit.

Entertainment Tonight called this speech “bonkers.”

That’s not fair.

Maybe a fourteenth lesson that McConaughey only hints at in his speech is: to achieve greatness you must dance along the edge of bonkers. To do anything worthwhile you must risk appearing ridiculous. On your journey, at many points, you will appear ridiculous. The fear of appearing ridiculous stops all too many from achieving their potential.

You know these No Fear t-shirts? I don’t get em. Hell, I try to scare myself at least once a day. I get butterflies every morning before I go to work. I was nervous before I got here to speak tonight. I think fear is a good thing. Why? Because it increases our NEED to overcome that fear.

Say your obstacle is fear of rejection. You want to ask her out but you fear she may say “no.” You want to ask for that promotion but you’re scared your boss will think you’re overstepping your bounds.

Well, instead of denying these fears, declare them, say them out loud, admit them, give them the credit they deserve. Don’t get all macho and act like they’re no big deal, and don’t get paralyzed by denying they exist and therefore abandoning your need to overcome them. I mean, I’d subscribe to the belief that we’re all destined to have to do the thing we fear the most anyway.

So, you give your obstacles credit and you will one. Find the courage to overcome them or see clearly that they are not really worth prevailing over.

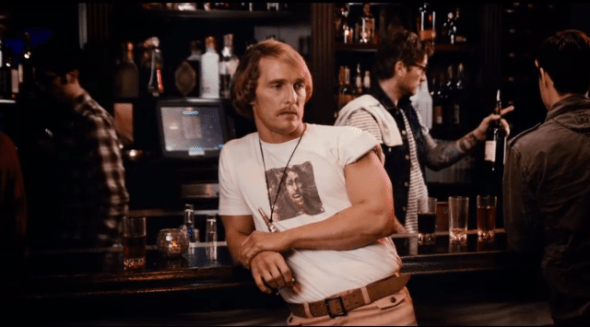

Here is what McConaughey looked like giving his speech.

Here is a great actor whose greatest role is himself.

* The Lincoln Lawyer spoke to a real fantasy I can’t be alone in having in Los Angeles: someone driving you everywhere in comfortable quiet. Since then Uber has come close to making that a reality.

The hero with a thousand faces

Posted: May 20, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, heroes, the California Condition 1 CommentThis

David Letterman

Posted: May 19, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, comedy, TV 2 CommentsGave me my first job ever. I only met him once, for thirty seconds.

I hated the actual work of working there. I had no idea how to write in this man’s voice, no clue what he was going to be into. I was terrible at it. On the show at that time he’d often throw out all the comedy and just telephone his assistant Stephanie on air instead. From my office I could see the Hudson River and I’d stare at tugboats going by. After six months I got fired.

Still it launched my career. People still ask me about it and probably will be for the rest of my life.

Steve Young had the office next to me, he’d been working there since 1989 or 1990. His office was full of records of industrial songs, and every once in awhile he’d play one for me. I remember one that was a rap that helped KFC employees remember how to make biscuits.

What a great man.

Another memory: every single day I ate the same thing: a BLT from Rupert’s deli downstairs.

Another one: they played the show, or at least the top ten list, on the radio. Sometimes, on my taxi ride home, the driver would be listening to it.

If you haven’t seen the last Norm MacDonald appearance there’s no helping you, but watch this old one. In these late episodes it’s easy to forget how sharp and fast and energized Letterman was at full strength.

The guy I’ll really miss though is Paul Schaffer.

“The secret I finally learned, after all these years, is just stay loose with this stuff,” says Paul Shaffer. “Swing with whatever happens onstage, because everybody else is.”

Stray Items

Posted: May 12, 2015 Filed under: Africa, America Since 1945, assorted, fscottfitzgerald, writing Leave a commentSorry I haven’t been posting more. Trying to finish my book and get Great Debates Live organized (get your tickets by emailing greatdebates69@gmail.com. We are legit almost sold out). Honestly it’s a LITTLE unfair to be mad at me for not producing enough free content.

A few items too good to ignore came across our desk:

1) Reader Robert P. in Los Angeles sends us this item:

Dear Helytimes,

Thought you might enjoy this wiki. There’s a great part about a riddle and another great part about conducting a trial. http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Numbers_Gang

Gotta say, this is one of the most intriguing Wikipedia pages I can remember. I love when Wikipedia takes myth at face value.

2) Re: our recent post about Tanya Tucker, reader Bobby M. writes:

Saw that Tanya Tucker’s Delta Dawn popped up. Love that one. We like to joke that the lyrics are a conversation wherein some jerk is taunting an insanse person. “Oh, and, Delta? Did I hear you say he was meeting you here today? And (aside to chittering friend: ‘get a load of this’) did I also hear you say he’d be taking you to his mansion. In the sky? Yeah, that’s what I thought you said, Delta. Nice flower you have on.” Midler’s version blows.

Bobby M. is one of the contributors to Lost Almanac, a truly funny print and online comedy mag.

3) We ran into reader Leila S. in New York City. She was reading the letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and sends in some highlights:

to John Peale Bishop, March, 1925, he wrote “I am quite drunk” at the top of the paper above the date, then later in the letter: “I have lost my pen so I will have to continue in pencil. It turned up– I was writing with it all the time and hadn’t noticed.”to H.L. Mencken, May 4, 1925, re: Great Gatsby:“You say, ‘the story is fundamentally trivial.'”

to Gertrude Stein, June 1925, after a long letter kissing her ass:

“Like Gatsby, I have only hope.” Dude quoted his own book he just wrote!

to Mrs. Bayard Turnbull, May 31, 1934, after a long apology about his embarrassing behavior at a tea party:“P.S. I’m sorry this is typed but I seem to have contracted Scottie’s poison ivy and my hands are swathed in bandages.”

to Joseph Hergesheimer, Fall 1935, re: Tender Is The Night“I could tell in the Stafford Bar that afternoon when you said that it was ‘almost impossible to write a book about an actress’ that you hadn’t read it thru because the actress fades out of it in the first third and is only a catalytic agent.”to Arnold Gingrich, March 20, 1936:“In my ‘Ant’ satire, the phrase ‘Lebanon School for the Blind’ should be changed to ‘New Jersey School for Drug Addicts.'” [The letter continues about other things, then at the very end, emphasis his] “Please don’t forget this change in ‘Ants.'”to Ernest Hemingway, August, 1936

“Please lay off me in print.”

As always you can reach helytimes at helphely at gmail.com

The News

Posted: May 5, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a commentMan, I miss Andrew Sullivan. I’d been reading him since he got rolling in 2001, when the Internet to me was just him and Salon.com (since devolved into deeply unreadable garbage).

Andrew Sullivan was interesting, almost every day. He changed sides, he was passionate. He posted disagreements people had with him, admitted he was wrong maybe not every time but plenty. He was not an idea tip-toer. He’d say things he knew would draw outrage and was prepared to be a rare dissenter when necessary.

One of the main ideas he had, that gay marriage might be a good idea, went from totally nuts to pretty much accepted reality, just in the time I was reading him. But he self-identified as conservative, he believed that sometimes very old ideas were still best thinking on a subject.

I could calibrate to him, feel his moods and changes, he became familiar to me. Sometimes he was frustrating, or overdramatic, or wrong-headed, but he still surprised, kept me engaged. When something happened I wanted his take.

The Internet’s worse without him.

Not sure there’s an exact connection, maybe there’s none, but lately: I haven’t cared too much about “the news”

I used to love “the news,” presidential elections especially. This time around though? It got me thinking about:

My memory of this book is of Sean Penn’s voice from the audiobook, as I drive back and forth to

After I was done with the audiobook, I gave the CDs to Justin Spitzer. Who knows what happened to after that. But I did remember Dylan (Sean Penn) saying something like: “I didn’t care about the news. ‘Mr. Garfield’s been shot down, shot down.’ To me, that was the news.”

The motto of Helytimes is GO BACK TO THE SOURCE, so I did.

As usual, I didn’t have it quite right.

Also got to thinking about Bob Dylan’s friend, Herman Melville. I (half-mis-)remembered a point he made, almost backhanded, about the news being awful repetitive:

Minus Ishmael, but with the misspelling, could that be on Drudge tomorrow?

Surprised to find how many interesting things I forgot from Chronicles. For example: been thinking myself lately about Robert E. Lee (mainly I guess because of Ta-Nahesi Coates’ writings on the Civil War).

Here is a man who fought for a country that kept humans as slaves. But he was also, in very many ways, indisputably excellent. Even (maybe especially) his enemies were in awe of him. In a way, maybe that’s his worst crime.

Here is a man who fought for a country that kept humans as slaves. But he was also, in very many ways, indisputably excellent. Even (maybe especially) his enemies were in awe of him. In a way, maybe that’s his worst crime.

Douglas Southall Freeman studied Lee more than anybody else ever had. That was while Freeman was also a newspaper editor (The Richmond News Leader) and sought-after advisor to Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall:

Freeman stresses how Lee, and some other generals, were objects of great affection among their men. They were spoken of like they were gods, even years after the war was over. One wonders if this was because of shared risks. One of the best books about the Vietnam War, The Long Gray Line*, notes that in the Civil War, the risk of battle death to a general was twice that of a private. (Whereas in eleven years of fighting in the Vietnam War, only three general officers were killed in action.) The halo effect over Lee is centered on his concern for the lives of his troops, particularly in never ordering them to make unwarranted charges into death traps.

How many World War II generals had grandfathers who fought with Lee?

What are we gonna do with this guy? How many high schools are named after him?:

How many high schools are named after him?:

Here is Bob Dylan’s take:

Dylan! Nobody else could put it quite the same way. He’s in his friends’ apartment, on Vestry Street if I read right, reading books. On Al Capone vs. Pretty Boy Floyd:

These people had the greatest apartment library in New York:

If Dylan had gone to West Point, I wonder if he would’ve ended up something like James Salter.

Also recommended:

Man. That one knocked my head off. Very glad I read it when I did, should read it again. Part of it is about North Korea. Not to be confused with:

Documentary tracking these women over the next fifty years

Posted: April 22, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

Aquarium Drunkard

Posted: April 22, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, music, the California Condition Leave a comment

Picked this one up from listening to Aquarium Drunkard‘s playlists on Spotify.

Don’t know anything about Aquarium Drunkard except passed-down oral legend and intend to keep it that way but I’m not the first to discover him — the guy is brightening my life with his (?) music curating.

Sherrill initially planned to have Tucker record “The Happiest Girl In the Whole USA,” but she passed on the tune to Donna Fargo, choosing “Delta Dawn” — a song she heardBette Midler sing on The Tonight Show — instead. Released in the spring of 1972, the song became a hit, peaking at number six on the country charts and scraping the bottom of the pop charts. At first, Columbia Records tried to downplay Tucker’s age, but soon word leaked out and she became a sensation. A year later, Australian singer Helen Reddy would score a No. 1 U.S. pop hit with her version of “Delta Dawn.”

She had begun drinking in her late teens, and she explained how it started: “You send your ass out on the road doing two gigs a night and after all that adoration go back to empty hotel rooms. Loneliness got me into it.” In 1978 Tucker moved to Los Angeles, California, to try, unsuccessfully, to broaden her appeal to pop audiences, and was quickly captivated by the city’s nightlife. She also said that she “was the wildest thing out there. I could stay up longer, drink more and kick the biggest ass in town. I was on the ragged edge.”

Worth having a look at Bette’s version if only for her outfit:

Tam Is Uniform For This Bridge Player

Posted: April 17, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a commentGuessing that Bobby from work is the only other person who maybe paused the Frank Sinatra HBO documentary to read some of the other articles.

It’s really too bad how much journalism has declined.

Shady Grove

Posted: April 16, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, music Leave a comment

In my foolish youth I thought Tom Petty was kind of a joke, until Bob Dylan in Chronicles woke me up hard.

Bob also has words of respect for Jerry Garcia:

What an eerie tune. Wikipedia is unusually quiet on this one.

Many verses exist,[citation needed] most of them describing the speaker’s love for a woman called Shady Grove. There are also various choruses, which refer to the speaker traveling somewhere (to Harlan, to a place called Shady Grove, or simply “away”)

The folks at mudcat.org take on the problem:

| Subject: Origins: ‘Shady Grove’ a mondegreen ? From: GUEST,Jake Date: 15 Aug 10 – 11:23 PMMulling (for the thousandth time) over the incongruity of ‘Shady Grove’ which is nothing about trees protecting the singer from the sun, but seems to be a woman’s name, it occurred to me in a flash of insight, that of course it must have started as a song about a Woman or girl named “Sadie” with the surname “Grove”, ie, “Sadie Grove”, and was corrupted by the usual vagaries of oral transmission, etc, etc. Searching this forum and the web generally provides no support for this conjecture, however. |

| Subject: RE: Origins: ‘Shady Grove’ a mondegreen ? From: MGM·Lion Date: 15 Aug 10 – 11:32 PMI have always shared this confusion: Shady Grove seems to be the woman’s name, but also the name of the place or location in which she lives, sometimes incongruously both at the same time. The fact that it’s one of those myriad songs [Going Down Town; Bowling Green …] which share pretty much the same set of ‘floaters’ doesn’t help.~Michael~ |

| Subject: RE: Origins: ‘Shady Grove’ a mondegreen ? From: Hamish Date: 16 Aug 10 – 03:18 AM”Wish I was in Shady Grove” takes on a new meaning.”When I was in Shady Grove I heard them pretty birds sing” (and the earth moved, no doubt). |

| Subject: RE: Origins: ‘Shady Grove’ a mondegreen ? From: GUEST,Lynn W Date: 16 Aug 10 – 04:11 AMThere is a comment on Wikipedia that the melody is similar to Matty Groves. Any connection, I wonder? |

| Subject: RE: Origins: ‘Shady Grove’ a mondegreen ? From: Jack Campin Date: 16 Aug 10 – 05:19 AMWikipedia has got it backwards. The folk-revival version of “Matty Groves” took its tune from “Shady Grove”. |

That’s as far down this hole as I can go at the moment.

I’d be shocked if any Helytimes readers hadn’t wikipedia’d The Child Ballads.

If demographizing the known Helytimes readership, I’d say “it’s people, mostly people I know, who have Wikipedia’d The Child Ballads.”

Still, why not a refresher on some best ofs?

Although shy and diffident on account of his working-class origins, he was soon recognized as “the best writer, best speaker, best mathematician, the most accomplished person in knowledge of general literature” and he became extremely popular with his classmates.

Child became the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory when he we was 26. Says an admirer, writing in the 1970s:

Child well understood how indispensable good writing and good speaking are to civilization, or as many would now prefer to say, to society. For him, writing and speaking were not only the practical means by which men share useful information, but also the means whereby they formulate and share values, including the higher order of values that give meaning to life and purpose to human activities of all sorts. Concerned as he thus so greatly was with rhetoric, oratory, and the motives of those mental disciplines, Child was inevitably drawn into pondering the essential differences between speech and writing, and to searching for the origins of thoughtful expression in English.

(Yes! That’s the good reason for being into this I’ve been looking for.)

Sometimes I picture Child backpacking around from pub to pub learning these things. Mostly, though, he got them from manuscripts.

Don’t you worry, he could cut loose sometimes:

he also gave a sedulous but conservative hearing to popular versions still surviving.

Child engaged

in extensive international correspondence on the subject with colleagues abroad, primarily with the Danish literary historian and ethnographer Svend Grundtvig, whose monumental twelve-volume compilation of Danish ballads, Danmarks gamle Folkeviser, vols. 1–12 (Copenhagen, 1853), was the model for Child’s resulting canonical five-volume edition of some 305 English and Scottish ballads and their numerous variants.

Child is buried in the Sedgwick Pie.

Is Kyra Sedgwick eligible for the Sedgwick Pie? Seems like she might be. Also seems a bit rude to ask a wonderful and very alive actress and mother if she’s given any thought to her grave.

Famously (? I guess, I never read the biography) not included:

Yaaass

Posted: April 11, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a comment

Not everyone likes Yass cat. Myself, I think it’s about the best seven seconds of filmmaking I’ve ever seen. I hate when people apply “perfect” to invariably flawed human works but this video is perfect.

Perfect performances, perfect editing, perfect lighting, perfect audio quality. Perfect three act structure.

Perfect.

An informant told me about Yaaaaaaas Gaga guy.

Think Piece About Mad Men

Posted: April 6, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing 1 CommentMad Men is great.

The writing is great.

The directing is great.

The actors are good.

The set decorating is great. Really colorful.

The main guy is cool and I like the stuff he does.

The other guys are funny.

The girls are hot and wear cool clothes.

There’s good stories, with surprises.

Sometimes I don’t know what’s happening but usually I figure it out or I just kinda go along.

So, I think, Mad Men is great.

Book I’m always recommending

Posted: March 11, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, writing 2 CommentsBill James you may know, if you read Moneyball or follow baseball. In the 1970s, while working as a nighttime security guard at a Van Camp’s pork and bean factory in Kansas, he spent his spare time researching interesting questions about baseball, writing them up, and self-publishing them:

A typical James piece posed a question (e.g.,“Which pitchers and catchers allow runners to steal the most bases?”), and then presented data and analysis written in a lively, insightful, and witty style that offered an answer.

Editors considered James’s pieces so unusual that few believed them suitable for their readers. In an effort to reach a wider audience, James self-published an annual book titled The Bill James Baseball Abstract beginning in 1977. The first edition of the book presented 80 pages of in-depth statistics compiled from James’s study of box scores from the preceding season and was offered for sale through a small advertisement in The Sporting News.

Bill James was also the last person from Kansas to be sent to Vietnam — that’s just the kind of trivia he likes to uncover, turn over, and then decide is interesting but irrelevant.

Bill James’ other passion is reading true crime books. In Popular Crime, he rounds up, summarizes, muses on what he’s learned from reading, he says, over a thousand true crime books.

This book has a fantastic table of contents, allowing you to skip about to the crimes that pique your particular interest:

It’s also written in a terrific, casual style, that trusts the reader’s common sense and intelligence. Here Bill James talking about how serial killers get caught, and a fact he’s concluded about serial killers:

Here’s an excerpt on the OJ case – chose this more or less at random to show his style:

A James question from me: why isn’t this book more popular? I think everyone I’ve recommended it to loves it, yet no one seems to have heard of it.

I’ve genuinely considered getting more into baseball just so I could read more of Bill James’ writings. It wouldn’t be right to call his style “amateurish,” but there’s something about it that’s free from professional stiffness, though I suspect it takes years of practice to sound this natural. It’s refreshing, and surprisingly rare. He’s not trying to sound like anything except himself.

Here’s an interview with James on the book conducted by Chuck Klosterman.

Helytimes Mailbag

Posted: February 25, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, movies Leave a commentLots of readers wrote to me to the effect “You got Wild completely wrong, this is a great movie.” A sample:

The fact that she can quit and has no reason to walk is what I liked. I don’t see it as a motivation problem. I like that we don’t know what she means to accomplish almost precisely because she doesn’t know what she wants. She just knows that the noise in her head telling her to act out and hurt herself and it’s turning her into a person who is different than the person she thought her mom wanted her to be. So that’s why she heads into nature. She never “arrives” so to speak, she just feels differently about herself by the time she gets to Ashland

Terrific! Thanks for writing. Like I said I thought it was pretty good.

Lots of incoming fire also came my way re: Selma. (Funny to do an image search for “Selma”). Let me quote from one:

Helytimes, I have a bone to pick with you. Selma was a great movie. I wept. I may not know everything about LBJ but this was a powerful movie and I don’t get why you were being so hard on it.

Another:

Why were you so hard on Selma without taking any shots at an even more historically inaccurate movie, The Imitation Game, which misrepresents Alan Turing’s character, is similarly “all over the place” and is just a mess?

Well what can I tell you: I didn’t think it was that good. It’s not an easy movie to make, surely. Should it get points for difficulty? Maybe! If you liked Selma, that’s terrific. I want you to have as many things to like as possible.

As for The Imitation Game — whatever, I can’t pay attention to everything! It seemed to me that movie took place in a kind of bizarro reality so whatever historical crimes were extra- beside the point. The Wikipedia folks seem to have it covered too:

Turing’s surviving niece Payne thought that Knightley was inappropriately cast as Clarke, whom she described as “rather plain”.

Harsh. I did wonder why the character played by Tywin Lanister was such an asshole to Alan Turing:

Was that real? Tywin is playing Alastair Denniston. Got this book:

and looked up every time Denniston appears, which is six times. He’s never once a jerk to Turing. This is the closest he comes:

Maybe Andrew Hodges just left that part out. Is it unfair to real-life person Denniston to make him out that way?:

Libby Buchanan, Denniston’s 91-year-old niece and god-daughter, said she recalled a “quiet, dignified” man who was devoted to his work.

Judith Finch, his granddaughter, added: “He is completely misrepresented. They needed a baddy and they’ve put him in there without researching the truth about the contribution he made.”

The film’s writer, Graham Moore, and producers said: “Cdr Denniston was one of the great heroes of Bletchley Park.

“As such, he had the perhaps unenviable position of being a layman overseeing the work of some of the century’s finest mathematicians and academics — a situation bound to result in conflict as to how best to get the job done.

“I would say that this is the natural conflict of people working extremely hard under unimaginable pressure with the fate of the war resting on their heroic shoulders.”

The part of Imitation Game I found most interesting was the idea that once they broke the code, Turing and the boys and Kiera Knightley worked out a system to use the information they had in a statistically measured way. Looked into this and couldn’t find much more about it. Seems like actually the way it worked is they limited access to the Enigma info to a small pool of top military commanders, and even that they were haphazard and bad at. This seemed like a decent article on that:

According to Gordon Welchman, who served at Bletchley Park for most of the war, We developed a very friendly feeling for a German officer who sat in the Qattara Depression in North Africa for quite a long time reporting every day with the utmost regularity that he had nothing to report.

Anyway: I love getting mail, thanks for taking the time, keep it coming – helphely at gmail is the way.

Some favs

Posted: February 20, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, the California Condition Leave a commentMournbrag

Posted: February 13, 2015 Filed under: advice, America Since 1945, death Leave a commentLook, the nature of grieving is weird, how are you gonna judge how somebody grieves? (but the typo?!)

This book:

first got me to really thinking about this.

George HW and Barbara Bush lost a daughter to pediatric leukemia when she was four years old. Cramer says that something like half of all couples that lose a child split up, because the ways that two people grieve can be so divergent and impossible, even offensive, for the other person to deal with. The Bushes were determined not to let that happen to them (and they didn’t).

The instinct on Twitter to make someone’s death an opportunity for backhanded aggrandizement sets my nerves on edge. I’m not sure why that particular thing gnaws at me so much. Maybe because the whole point of the death of a noble guy, or death at all, might be to remind us how unimportant we are, or to encourage us to be better?

(Hardly a perfect model here: when SDB died I both wanted to talk about him and myself and also at the same time never talk about it.)

This dude David Carr was incredible, his death was shocking, the number of people he seemed to have touched directly is staggering. In New York in 2009 I was talking to a girl who told me more or less unprompted about truly moving kindnesses and generosity David Carr had extended to her just out of excellence of character and goodness of spirit.

I’ll miss reading the guy’s stuff. I was just reading his thing about Brian Williams because I’m sure he’d have something to say worth hearing.

Now this is a tribute:

If you can only have one sentence of writing advice, go with this:

“Keep typing until it turns into writing”

If you are prepared for an intense experience on the subject of death and grieving, might I recommend the American Experience “Death And The Civil War”?

If you’re rushed for time, allow me to summarize: the Civil War was a tremendous bummer.

Plan to redeem Brian Williams

Posted: February 12, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, TV Leave a commentThink this is a legitimately good plan:

Brian Williams announces he will buy a beer for every single American who’s ever actually been shot at in a military helicopter.

Ten city tour. If you were once on a shot-at helicopter, go to the most convenient stop (they’ll be bars or VFW halls or something) and Brian Williams will buy you a beer and shake your hand. You can tell him your story which will be good for him as a reporter.

In this way this beloved public figure can do serious penance and redeem himself and show he’s solid.

If he wants to provide pizza, that’s ok. If he’s asking for my advice I’d say also go ahead and get pizza. And good root beer for anyone who’s sober.

Learned an interesting bit of trivia about newsman Bob Schieffer the other day:

Shortly after President Kennedy was shot in Dallas, while in the Star-Telegram office, he received a telephone call from a woman in search of a ride to Dallas. The woman was Marguerite Oswald, Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother, whom he accompanied to the Dallas police station. He then spent the next several hours there pretending to be a detective (the first of many deceptions during his career), enabling him to have access to an office with a phone. In the company of Oswald’s mother Marguerite and his wife, Marina, he was able to use the phone to call in dispatches from other Star-Telegram reporters in the building. This enabled the Star Telegram to create four “Extra” editions on the day of the assassination.

Well I hope you’re wrong, Leslie Gelb!

Posted: February 2, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945 Leave a commentfrom this roundup of predictions for “The World in 2030” from Politico Magazine:

No breakthroughs for the better

By Leslie Gelb, president emeritus and board senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations

The world of 2030 will be an ugly place, littered with rebellion and repression. Societies will be deeply fragmented and overwhelmed by irreconcilable religious and political groups, by disparities in wealth, by ignorant citizenry and by states’ impotence to fix problems. This world will resemble today’s, only almost everything will be more difficult to manage and solve.

Advances in technology and science won’t save us. Technology will both decentralize power and increase the power of central authorities. Social media will be able to prompt mass demonstrations in public squares, even occasionally overturning governments as in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, but oligarchs and dictators will have the force and power to prevail as they did in Cairo. Almost certainly, science and politics won’t be up to checking global warming, which will soon overwhelm us.

Muslims will be the principal disruptive factor, whether in the Islamic world, where repression, bad governance and economic underperformance have sparked revolt, or abroad, where they are increasingly unhappy and distained by rulers and peoples. In America, blacks will become less tolerant of their marginalization, as will other persecuted minorities around the world. These groups will challenge authority, and authority will slam back with enough force to deeply wound, but not destroy, these rebellions.

A long period of worldwide economic stagnation and even decline will reinforce these trends. There will be sustained economic gulfs between rich and poor. And the rich will be increasingly willing to use government power to maintain their advantages.

Unfortunately, the next years will see a reversal of the hopes for better government and for effective democracies that loomed so large at the end of the Cold War.

Coaches, Part 2: Belichick

Posted: January 29, 2015 Filed under: America Since 1945, New England, sports Leave a comment(Part One, about Pete Carroll and Nick Saban’s memoirs, is here)

The most interesting character in this book isn’t Belichick, it’s Ernie Adams.

Photo by Stu Rosner from this Northwestern magazine article: http://www.northwestern.edu/magazine/winter2008/feature/adams.html

Ernie Adams, it should be noted, was a coach even before entering Andover. he had gone to elementary and junior high at the Dexter School, a private school in the Boston area (where John F. Kennedy had gone), and being more passionate about football than the teacher who had been drafted to coach the intramural team there, he had ended up giving that teacher more suggestions than the teacher wanted to hear. Finally the teacher, in desperation, had turned to Ernie and said, “Well, if you know so much, why don’t you coach?” That was an offer Ernie Adams could not turn down, and he ended up coaching the Dexter team quite successfully.

At Andover he had already befriended another football-crazed classmate, Evan Bonds, with whom he talked constantly and with whom he diagrammed endless football plays and with whom he jointly did the senior project breaking down and analyzing all of Andover’s plays from the their senior season…

Bonds felt that although his own life revolved completely around football, Adams was already a good deal more advanced in his football obsessions, going off on his own to coaching clinics where everyone else was at least ten years older, collecting every book written by every coach on the game, the more technical the better, and collecting films of important games: “Ernie already had an exceptional football film collection, sixteen-millimeter stuff, the great Packer-Cowboy games, Raiders-Jets, films like that, which he somehow found out about through sports magazines, had sent away for, and for which he had enough primitive equipment that he could show the films,” Bonds said. “It’s hard to explain just how football crazed we were, but the year before Bill arrived, when we were in the eleventh grade, and it was spring, the two of us went down to Nickerson Field, the old Boston University field, because BU was having an intra-squad spring game. We were up there in the stands, taking notes, these two seventeen-year-olds – can you believe it? – scouting an intra-squad game at BU on our own, and I still have no earthly idea what we would have done with the notes. Anyway, pretty soon a BU assistant coach came up looking for us, to find what we were doing, and why we were doing it. So we said we were from Northeastern, as if that would give us extra legitimacy, and the coach said what we were doing was illegal, and we had to get out then and there.”

And then at Andover arrived young Bill Belichick, doing a post-graduate year, a kind of bonus senior year after graduating from Annapolis High, in the hopes of getting into a better college:

Adams was already as advanced a football junkie as Belichick: he had an exceptional collection of books on coaching, including Football Scouting Methods ($5.00 a copy, published by the Ronald Press of New York City, and featuring jacket quotes from, among others, the legendary Paul Brown: “Scouting is essential to successful football coaching.”), the only book written by one Steve Belichick, assistant coach of the Naval Academy. The book was not exactly a best seller – the author himself estimated that it sold at most four hundred copies – nor was it filled with juicy, inside tidbits about the private lives of football players. Instead it was a very serious, very dry description of how to scout an opponent, and, being chockful of diagrams of complicated plays, it was probably bought only by other scouts and the fourteen-year-old Ernie Adams.

That year, just as the first football practice was about to start at Andover, Coach Steve Sorota posted the list of the new players trying out for the varsity, including the usual number of PGS – the list included the name Bill Belichick, and Ernie Adams was thrilled. That first day Adams looked at the young man with a strip of tape that Belichick on his helmet, and asked if he was from Annapolis, Maryland, and if he was related to the famed writer-coach-scout Steve Belichick, and Bill said yes, he was his son. Thus were the beginnings of a lifetime friendship and association sown…

..”Because we were such football nerds, it was absolutely amazing that Bill had come to play at Andover, because we were probably the only two people in the entire state of Massachusetts who had read his father’s book,” Bonds said years later.

Belichick and Adams, traceable through http://www.patsfans.com/new-england-patriots/messageboard/threads/rare-photos-of-bill-belichick.813505/

Adams has more or less been at Belichick’s side ever since, “Belichick’s Belichick,” aside from interludes on Wall Street. Here’s a good profile on him, with quotes from Andover classmate Buzz Bissinger. (Apparently Jeb Bush was in that class too).

So you can never really tell what is going on in his head. But I did get Carlisle to call Adams on Monday and ask for his five favorite books, hoping to get a window into the places a man like him goes for inspiration. Here is the list:

- “The Best and the Brightest,” by David Halberstam

- “The Money Masters of Our Time,” by John Train

- Robert Caro’s three-volume biography of Lyndon B. Johnson

- Robert Massie’s biography of Peter the Great

- William Manchester’s two-part biography of Winston Churchill

…

Adams also seems to enjoy not only watching greatness work, but also seeing it fail. Carlisle thinks the central message of Halberstam’s Vietnam classic appeals to Adams: that people incredibly well-educated and well-intentioned could be so flat-out wrong about something. It’s a helpful notion to keep in mind about the conventional-wisdom-obsessed world of football, where pedigree and tradition dictate many overly conservative decisions. Indeed, when Adams agreed to participate in Halberstam’s Belichick book, he did so with this caveat: For every two questions the journalist got to ask Adams about football, Adams got to ask one back about Vietnam. Did that trait allow Adams to make sure the mistakes of Belichick in Cleveland were not repeated? Maybe.

Most articles on Adams will include this detail:

When Belichick and Adams were together when the coach was in Cleveland, Browns owner Art Modell once said, “I’ll pay anyone here $10,000 if they can tell me what Ernie Adams does.”

Or:

A few years back, during a team film session, the Patriots players put up a slide of Adams. The caption read: “What does this man do?” Everyone cracked up. But no one knew.

Mysterious, rigorous, intense, scholarly dissection of football — that seems to be the Belichick way. “Unadorned,” as Halberstam puts it:

Belichick doesn’t seem like the kind of dude to write a book, least of all a peppy all-purpose motivational paperback like Pete Carroll’s. This is the closest thing, a kind of biography starting with the arrival of Bill Belichick’s grandparents in America. They came, like Belichick apprentice Nick Saban’s grandparents and Pete Carroll’s maternal grandparents, from Croatia:

Bill Belichick grew up in football. His dad, Steve Belichick, spent the bulk of his career (33 years) as an assistant coach at the Naval Academy. (As a young guy, a fellow coach advised him to get a tenure-track job as an associate professor of physical education, so he had job security even as eight head coaches passed through.) Belichick’s mom seems like a great lady — she’d done graduate work in languages at Middlebury, and during the war she translated military maps. She learned Croatian so she could speak to her in-laws more easily.

Bill Belichick grew up in football. His dad, Steve Belichick, spent the bulk of his career (33 years) as an assistant coach at the Naval Academy. (As a young guy, a fellow coach advised him to get a tenure-track job as an associate professor of physical education, so he had job security even as eight head coaches passed through.) Belichick’s mom seems like a great lady — she’d done graduate work in languages at Middlebury, and during the war she translated military maps. She learned Croatian so she could speak to her in-laws more easily.

Though he never worked at Oakland, Belichick apparently picked up several things from the way Al Davis ran the Raiders:

There were important things that [assistant coach Rich] McCabe told Belichick about the Davis system that would one day serve Belichick well. The first thing was that Oakland looked only for size and speed. Their players had to be big and fast. That was a rule. If you weren’t big and fast, Oakland wasn’t interested. The other thing was about the constancy of player evaluation. Most coaches stopped serious evaluation of their personnel on draft day – they chose their people, and that was that. But Davis never stopped evaluating his people, what they could do, what you could teach them, and what you couldn’t teach them. He made his coaches rate the players every day. Were they improving? Were they slipping? Who had practiced well? Who had gone ahead of whom in practice? The jobs the starters had were not held in perpetuity.

This is similar to stuff Carroll talks about — everyone is competing every practice. After a stint in Denver:

That summer [Belichick] came home and visited with his boyhood friend Mark Fredland and told him he had found the key to success: It was in being organized; the more organized you were at all times, the more you knew at every minute what you were doing and why you were doing it, the less time you wasted and the better coach you were.

Halberstam likes Belichick, obviously. They had become friendly because they both had houses on Nantucket, and Halberstam suggests that the gruff Belichick we see is part presentational strategy:

That persona – the Belichick who had never been young – was one he had either created for the NFL or had evolved because of the game’s needs. Part of the design was more or less deliberate, and part of it was who he was. For when he had first entered the League, he had been a young man teaching older men, and he had needed to prove to them he was an authority figure. Thus, he believed, he had been forced to be more aloof and more authoritarian than most coaches or teachers working their first jobs.

Compare this to the young guy at Wesleyan with his frat brothers, sneaking a case of beer into a showing of Gone With The Wind (why that movie? even Halberstam is baffled) under his parka.

The best parts of this book are about Belichick’s relationship with Bill Parcells, when they were at the Giants. The biggest issue there was how to handle Lawrence Taylor, who was supremely excellent at football, but semi-out of control on drugs and women, prone to nodding off in meetings though he would somehow intuitively understand what he had to do in complex plays. A great anecdote — LT has injured his ankle:

So on his own, without telling the coaches, he went to a nearby racetrack and somehow managed to find someone there who was an expert in horse medicine, who had some kind of pill – a horse pill – and he took it and played well.

Belichick’s takeaway from dealing with LT was, apparently, never to bend the rules for anyone.

Parcells and Belichick needed each other, but they weren’t friends exactly:

There was one terrible moment, during a game, when Belichick called a blitz, and Parcells seemed to oppose it. They went ahead with it and the blitz worked – the other team did what Belichick had expected, not what Parcells had – but Parcells was furious, and over the open microphones in the middle of a game, he let go: “Yeah, you’re a genius, everybody knows it, a goddamn genius, but that’s why you failed as a head coach – that’s why you’ll never be a head coach… some genius.” It was deeply shocking to everyone who heard it; they were the cruelest words imaginable.

Not true, though. Belichick got to be head coach at Cleveland, where he didn’t really get on with owner Art Modell or QB Bernie Kosar and had a tough time, going 36-44 there. Halberstam almost seems to admire how bad/stubborn/unhelpful Belichick was with the media there.

And then he got to New England (taking over for the fired Pete Carroll).

As his friend Ernie Adams said, “The number one criteria for being a genius in this business is to have a great quarterback, and in New England he had one, and in Cleveland he did not.”

The stuff in Halberstam’s book about Belichick’s decision to go with Brady over Drew Bledsoe is pretty great:

But among those most impressed by Belichick’s decision to go with Brady was his father. Steve Belichick thought it was a very gutsy call, perhaps the most critical call his son had ever made, because the world of coaching is very conservative, and the traditional call would be the conservative one, to go with the more experienced player in so big a game. The way you were protected if it didn’t work out, because you had gone with tradition and experience, and no one could criticze you. That was the call most coaches would have made, he said, under the CYA or Cover Your Ass theory of coaching. Many of his old friends disagreed with what his sone was doing, he knew, but he was comfortable with it himself. When friends who were puzzled called him about it, he told them that Bill was right in what he was doing. “He’s the smart one in the family, and I’m the dumb one,” he would say.

Brady seems like he earned it, surely, and he had the special thing Belichick needed:

There were some quarterbacks who were very smart, who knew the playbook cold, but who were not kinetic wonders, and could not make the instaneous read. That was the rarest of abilities, the so-called Montana Factor: the eye perceiving, and then even as the eye perceives, transferring the signal, eye to brain, and then in the same instant, making the additional transfer from brain to the requisite muscles. The NFL was filled with coaches with weak arms themselves, who could see things quickly on the field but who were doomed to work with quarterbacks who had great arms, but whose ability to read the defense was less impressive. What Brady might have, they began to suspect, was that marvelous ability that sets the truly great athletes apart from the very good ones. Or as one of the assistants said, it was like having Belichick himself out there if only Belichick had had a great arm. In the 2001 training camp Brady would come off the field after an offensive series, and Belichick would question him about each play, and it was quite remarkable: Brady would be able to tell his coach what every receiver was doing on each play, what the defensive backs were doing, and explain why he had chosen to throw where he had. It was as if there were a camera secreted away in his brain. Afterward, Belichick would go back and run the film on those same plays and would find that everything Brady had said was borne out by the film.

There’s no secret in this book. Belichick is obsessed with analyzing football, has been since he was at least seventeen, probably younger. Even with that intensity it took luck and circumstance to get him five Super Bowl rings. A lesson from the coaching careers of Carroll and Belichick might be perseverance, but I don’t think that’s even the word for this — it’s not like it’s any kind of choice with these guys, it’s nature.

I read one other Halberstam sports book a few years ago, The Amateurs, about Harvard rowing. The theme of that book is similar: obsessive characters irresistibly driven, almost forced by their nature to be completely devoted, single-minded, unrelenting. There was no end of it. “The kind of guys whose idea of a day off is to drive up to New Hampshire and cross-country ski until you couldn’t stand up,” as a rowing coach put it.

Most of us (me) aren’t this kind of guy, certainly not about football or rowing. The compelling thing about the Pete Carroll book is that he seems semi-human. He seems to find joy and fun in this pursuit. Not that he’s any less competitive than Belichick, and who knows what eats him up in private. But he can explain what he’s doing to others in a way that seems born out of enthusiasm and positivity rather than just some incomprehensible inner nature. Just being willing to try to explain it is something.

That’s not typical:

“Don’t do it, don’t go into coaching,” the famed Bear Bryant had counseled young acolytes who were thinking of following him into the profession, “unless you absolutely can’t live without it.”

There was a constant loneliness to the job, a sense that no one else understood the pressures you faced. Each year, before the season began, Belichick would tell his team that no one else would understand the pressure on them, not even the closest members of their families. The person in football who knew him best and longest, Ernie Adams, thought Belichick had remained remarkably true to the person he had been as a young man. Adams was a serious amateur historian, and he was not a coach who threw the word “warrior” around to describe football players, because they were football players, not warriors, and the other side did not carry Kalashnikovs. Nonetheless, he thought the intensity under which the game was now played and the degree to which that intensity separated players and coaches from everyone else, even those dear to them, was, in some way, like combat, in that you simply could not explain it to anyone who had not actually participated. It was not a profession that offered a lot in the way of tranquility. “My wife has a question she asked me every year for ten years,” Bill Parcells said back in 1993 when he was still married, “and she always worded it the same way: ‘Explain to me why you must continue to do this. Because the times when you are happy are so few.’ She has no concept.”

(A good roundup of Belichick stories here.)